Abstract

The Impostor Phenomenon describes people characterized by a non-self-serving attributional bias towards success. In this experimental between-subjects design, we conducted a bogus intelligence test in which each subject was assigned to a positive or negative feedback condition. Our sample consisted of N = 170 individuals (51% female). The results showed that the impostor expression moderates the influence of feedback on locus of causality and stability attribution. ‘Impostors’ show an external-instable attributional style regarding success and an internal-stable attributional style regarding failure. Therefore, the relationship between the impostor expression and its characteristic attribution patterns could be experimentally validated for the first time. In addition, we investigated whether the IP is linked to the performance-related construct mindset. We found a positive correlation between the IP and fixed mindset. Possible causes for these findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Impostor Phenomenon (IP) describes the tendency of successful individuals to attribute successes externally and failures internally, leading to a discrepancy of objective success and a subjective sense of incompetence and self-doubt (Clance, 1985; Clance & Imes, 1978). The discrepancy between self- and reflected appraisal results in a feeling of fraudulence and fear of being exposed as an impostor (Kolligian & Sternberg, 1991). This dysfunctional pattern of cognitions is to be distinguished from actual imposture, in which a person fraudulently seeks to give the impression of being better than he or she actually is (Dunning & Kruger, 1999). To protect their poor self-esteem from negative judgment, impostors tend to adopt maladaptive work styles when faced with upcoming performance situations. They either overprepare excessively (procrastination), or postpone starting a task until the last possible moment and work in a frenzied manner (procrastination; Sakulku & Alexander, 2011). The consequence of both working styles is the attribution of their successes to extraordinary effort, luck, or sympathy (Clance, 1985) and, conversely, the attribution of failures to their incompetence (Brauer & Wolf, 2016).

The IP is a continuous individual difference variable that is stable over time and has a multidimensional theoretical foundation (Mak et al., 2019). This personality trait is characterized by feelings of inferiority, fear, self-deprecation, and inclinations to an external locus of control. The IP shares overlap with the DSM-III-R Cluster C (Ross & Krukowski, 2003) and shows strong associations with neuroticism (Ibrahim et al., 2020), depression (McGregor et al., 2008), and self-criticism (Kolligian & Sternberg, 1991). Impostors exhibit performance-related anxiety (Fried-Buchalter, 1992) and lower academic and global self-confidence (Thompson, 1994) but, in contrast, also high self-expectations (Clance, 1985) and maladaptive perfectionism (Pannhausen et al., 2020). The impostor’s self-esteem is dependent on outstanding performance, and the contrast between perfectionistic strivings and fear of failure results in a contrasting achievement motivation comprising approach and avoidance orientations (Ross & Krukowski, 2003; Whitman & Shanine, 2012 The motivational discrepancy explains the increased stress response; for instance, burnout components (emotional exhaustion and depersonalization) are enhanced in impostors (Villwock et al., 2016). Their hypercritical self-appraisals and dysfunctional strive for perfection are based on the need to maintain their positive public image and protect their self-esteem, as illustrated by the connection between IP and tendencies to self-handicapping (Want & Kleitman, 2006). Also, the lower expressed performance expectations in public but not in private sittings indicate the self-presentational quality of the IP (Leary et al., 2000). Impostors are therefore more performance-goal oriented. In addition, impostors show less confidence in their intelligence (Kumar & Jagacinski, 2006). Both aspects represent an intersection with the construct (fixed) mindset, characterized by an implicit theory of intelligence as fixed and self-presentational concerns in achievement situations (Elliot & Dweck, 1988).

Fixed Mindset

The dimensional construct mindset describes the implicit theory of intelligence. The poles of this continuum are the fixed mindset, the belief that intelligence and abilities are unchangeable (entity theory), and the growth mindset, the belief that intelligence and abilities are malleable (incremental theory). Research shows that individuals with a fixed mindset attribute failure internally to their abilities (Dweck, 2006). Therefore, mistakes reduce their performance to a greater extent compared with people showing a growth mindset (Dweck & Yeager, 2019). In addition, entity theorists attribute their success more externally (Licht & Dweck, 1984), similar to impostors (Brauer & Wolf, 2016). Also, the belief for effort as evidence of low intelligence and ability is present in both impostors (Clance & O’Toole, 1987) and entity theorists (Miele et al., 2013). Individuals with a fixed mindset exhibit a performance-goal orientation (Dweck & Leggett, 1988), leading to an increased expression in impression management (Burnette et al., 2013). The result is an inhibited perception of learning opportunities and the avoidance of performance situations (Dinger et al., 2013). The intention to present one’s intelligence is prioritized over developing oneself through mistakes and performance feedback. Self-presentational concerns in achievement tasks are also present in impostors, who seek to protect their self-worth (Ferrari & Thompson, 2006). Like impostors, entity theorists view negative feedback as an indicator of low ability, leading to increased affective appraisal of information relative to the self (Mangels et al., 2006). King (2017) showed that a fixed mindset is positively related to negative but not positive affect. Nevertheless, a fixed mindset inhibits the positive affect during challenging achievement tasks due to self-deprecation when extra effort is required to succeed (Dweck, 2006; Robins & Pals, 2002). The constructs mindset and IP show various intersections, such as avoiding achievement situations, a dysfunctional attributional style, and the high priority for maintaining a positive public image. Due to the theoretical overlap of the constructs and a successful IP coaching that addressed mindset in particular (Zanchetta et al., 2020), we examine the relationship between mindset and the IP in this study.

The non-self-serving attribution of impostors

Attributions intend to explain events and their origin. Causal attributions can range on the dimensions of globality (whether the cause appears in all or specific situations only), locality (the extent to which the cause is within the person), and stability (the extent to which the cause is changeable). The internal, stable, and global attribution of success and the external, unstable, and non-global attribution of failure is called the self-serving attributional style. This attribution pattern maintains self-esteem and fosters future expectations of achievement success (Seligman, 2006; Brauer & Wolf, 2016) found that, contrary to the self-serving attributional style, impostors show external-instable attributions in positive performance situations while controlling for depression. Conversely, an internal-stable attribution was only shown in negative performance situations when not controlling for depression. This maladaptive attribution pattern is a core component of the IP (Clance, 1985).

Interestingly, Morris and Tiggemann (2013) found a relationship between academic success and a stable and global failure attribution in high-achieving students, which they explained with the IP. According to the impostor cycle, high-achieving students show an increased fear of failure and achievement pressure (Kolligian & Sternberg, 1991), leading to pro- or precrastination in achievement tasks (Want & Kleitman, 2006). Furthermore, the success could lead to a perceived elevation of their public image. With the build-up of non-internalized successes, the discrepancy between the perceived public expectations and one’s competence perception increases. The result could be developing fraudulent ideations (Sakulku & Alexander, 2011), which lead to higher tendencies in impression management (Ferrari & Thompson, 2006) and the feeling of being an impostor. Therefore, the external-instable attribution of success is considered a central component of the IP.

Correlational studies indicated the internal-stable-global failure attribution and external-stable success attribution in impostors (Ibrahim et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the effect of the IP expression on the external-instable attribution of success and internal-stable attribution of failure has not been experimentally validated yet. In a sample of students, Cozzarelli and Major (1990) found that impostors showed an increased expression of defensive pessimism and more fear of exams than non-impostors, despite finding no differences in objective indicators of performance. Impostors also showed a lower self-serving attributional style in the face of failure and attributed the failure more to low ability. After subjective failure, impostors, therefore, felt worse and showed a greater reduction in self-esteem than non-impostors. However, in the case of personal success, impostors did not differ in their mood or self-confidence from non-impostors. Cozzarelli and Major (1990) stated that their findings regarding a common affective reaction after success indicate a reformulation of the construct because the IP characteristic of discounting praise (Clance, 1985) seemed not to apply in impostors.

Thompson et al. (1998) also investigated the attributional style of impostors using a vignette experiment, which simulated hypothetical situations describing success or failure. Again, impostors attributed failure more internally and generally than non-impostors. Nevertheless, they found no significant correlation between the IP and the external attributions of success.

In a between-subject design, Thompson et al. (2000) examined the IP using a Stroop color-word task and inducing either a success or failure condition by displaying high- or low-frequency mistakes. They found that the IP was related to perfectionistic concern over mistakes, anxiety, and negative affect. However, they found no interaction between the impostor expression and success (low-frequency mistakes condition) on external attribution. Thus, the external attribution of success could not yet be experimentally validated.

Due to the central importance of the external attribution of success in the theoretical formulation of the IP (Sakulku & Alexander, 2011), the lack of experimental validation so far raises an important question. Does the theoretical construct need to be reformulated, or is a different experimental design required to capture the impostors’ external attribution of success?

Prior experiments divided the test subjects into impostors and non-impostors, despite the dimensionality of the construct. In addition, the samples compared were partly uneven and small (Thompson et al., 2000). Further, the vignette experiment and the Stroop test may not have sufficient importance for the participants to find the theoretically postulated effects on attributional style and affect.

Aim of this study

Our study intends to examine the interaction of positive and negative feedback and the IP on the attributional dimensions locus of causality and stability. In addition, we want to investigate the relationship between mindset and the IP. Due to the lower internal locus of control in impostors (Brauer & Wolf, 2016), we hypothesize the following relationships:

H1

The IP expression and personal control correlate negatively.

H2

The IP expression and external control correlate positively.

The theoretical conception of the IP proposes a non-self-serving attribution style of success and failure, which was psychometrically (Ibrahim et al., 2021), but not experimentally supported. In an experimental between-subjects design, we want to examine the moderating role of the IP in a positive or negative feedback condition. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H3

The IP expression moderates the effect of feedback (positive or negative) on the locus of causality so that a high IP expression relates to external attributions of success and internal attributions of failure.

Ibrahim et al. (2021) reported a positive correlation between the IP and stable attribution in negative situations and a negative correlation between the IP and stable attribution in positive situations. Based on these findings, we hypothesize:

H4

The IP expression moderates the effect of feedback (positive or negative) on the stability attribution so that a high IP expression leads to instable success attribution and a stable failure attribution.

Due to theoretical intersections between the constructs fixed mindset and the IP like avoidance-orientation, anxiety-driven achievement motivation, and an increased error sensitivity (Elliott & Dweck, 1988; Ross & Krukowski, 2003), the authors hypothesize:

H5

The IP expression and the fixed mindset expression correlate positively.

Method

Participants

The German sample was generated using an online survey from May to June 2021. The total sample size of N = 170 contained n = 83 men (48.8%), n = 86 women (50.6%) and one non-binary person (0.6%). The German sample consisted mostly of students (n = 101 students; 59.4%) and employees (n = 44, 25.9%). The age ranged from 19 to 66 years (M = 29.54; Md = 24.00, SD = 11.54; see online Supplement materials for full details on sample characteristics). The dataset for this study can be found in the open science framework: https://osf.io/2kdup/?view_only=5f617462feaf4648af66dc616d2b4b94.

Instruments

Impostor Profile 30 (IPP30)

The German-language IPP30 (Ibrahim et al., 2021) comprises 30 items and assesses the impostor expression across six subscales (Competence Doubt, Working-Styles, Alienation, Other-Self Divergence, Ambition, and Need for Sympathy) and a total score. The instrument uses a visual analogous scale ranging from 1 (does not apply in any aspect) to 100 (applies completely). The reliability of the six subscales ranges from ω = 0.50 to 0.91, with the total score showing very good internal consistency (ω = 0.95; Ibrahim et al., 2021).

Growth Mindset Scale

The Growth Mindset Scale (Dweck, 2006) comprises three items and uses a six-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The scale captures the implicit theory of intelligence from a fixed mindset (entity theory) to a growth mindset (incremental theory). The scale’s internal consistency is excellent (α = 0.94 – 0.98; Dweck et al., 1995). This article used a German translation of the scale, back- and forth-translated twice for validation. The German version of the scale shows very good internal consistency (α = 0.89).

Revised causal dimension scale (CDSII)

The Revised Causal Dimension Scale (McAuley et al., 1992) is based on Weiner’s (2000) achievement motivation and attribution theory. This study used a professionally pre- and back-translated German version comprising 12 items measuring the four subscales locus of causality, personal control, stability, external control with a nine-point Likert scale. The scale ranges, e.g., for the locus of causality, from 1 (reflects an aspect of the situation) to 9 (reflects an aspect of myself). The internal consistencies of the scales are very good α = 0.87–89.

Procedure

The experiment was conducted online with the survey platform Questback (version EFS Summer 2021) from May to June 2021. To test the credibility and a sufficient level of difficulty of the bogus performance test, we conducted a pre-test phase (n = 10). As a result, all subjects rated the bogus construct as credible. In addition, pre-test participants rated the task difficulty of the performance tests as moderate (n = 8) to very difficult (n = 2). At the beginning of the experiment, the subjects were informed about the bogus construct called the inductive-holistic problem-solving competence, which was described in the instruction as a stable personality trait and as a prognostically valid indicator of future academic and career success. The construct was described as a stable personality trait and valid indicator of future success to increase candidates’ motivation and effort and, therefore, to prevent the external attribution of negative feedback on lacking effort. In addition, we intended to increase the meaning of the feedback. The IPP30 and the Growth Mindset Scale were assessed in the next step. Afterwards, the first part of the bogus experiment was conducted, which contained 24 items on different personality traits. The second part of the test contained parts of the Wilde Intelligence Test-2 (WIT-2; Kersting et al., 2008) with spatial, numerical, and verbal reasoning tasks. The performance tasks were carried out under time pressure. Subsequently, after completing the performance task, the participants were shown a short waiting screen for the illusion of calculating the results. After that, the subjects received a randomized positive or negative bogus performance feedback written as follows (translated from German):

Positive performance feedback.

“You scored above average to far above average on the performance test. In the area of inductive-holistic problem-solving skills, your score is better than 82%. In the area of adaptive regulation skills, your score is better than 89% of participants in previous studies. Inductive-holistic problem-solving competence: PR = 82, 95% CI [79.31, 89.10]. Adaptive regulatory ability: PR = 89, 95% CI [85.08, 93.70].”

Negative performance feedback.

“You scored below average to far below average on the achievement test. In the area of inductive-holistic problem-solving skills, your score is better than 16%. In the area of adaptive regulation skills, your score is better than 23% of participants in previous studies. Inductive-holistic problem-solving competence: PR = 16, 95% CI [13.51, 19.40]. Adaptive regulation ability: PR = 23, 95% CI [21.73, 27.85].”

Next, a manipulation check was carried out in which subjects had to indicate whether their inductive-holistic problem-solving competence was above average (1 = true; 2 = not true). Afterwards, the CDSII was assessed. In the last step, the subjects were informed about the deception and the true objective of the research. Finally, the subjects were told that the feedback was randomly generated and that they could withdraw their participation and have their data deleted.

Analytic technique

We used the software R (R Core Team, 2016) to test the moderation and correlation models. We computed the interaction terms using mean centering and examined the IP as the moderator at a high (+ 1SD, n = 37, M = 67.38), mean ( < + 1SD and >-1SD, n = 108, M = 43.93), and low (-1SD, n = 25, M = 37.40) level. The interaction effects of the feedback condition and impostor expression were examined for the subscales locus of causality and stability.

A power analysis was conducted for multiple linear regression models with two (for moderation analysis) predictors and revealed a power of 0.80 for small effects (f² < 0.15) with a sample size of n = 159 participants. For a oneway bivariate correlation analysis with a significance level of α = 0.05, a minimum sample size of n = 153 was determined to find a small effect of r = .20 with a power of 0.80 (Cohen, 1988; Faul et al., 2007).

Results

The descriptive statistics and reliabilities for the assessed scales are reported in Table 1. The correlations of the study variables are briefed in Table 2. As expected, the IPP total score correlates negatively with the CDSII subscale personal control (r = − .34, p < .001; H1) and positively with external control (r = .30, p < .001; H2). The locus of causality scale (internality attribution) is not related to the IPP total score (r = − .93, p = .230). However, the separate examination of the subgroups regarding the feedback condition shows that the impostor score is negatively related to internal attribution in the case of positive feedback (r = − .45, p < .001) and positively related to internal attribution in the case of negative feedback (r = .29, p = .008). Also the stability scale is not related to the IP (r = − .07, p = .387). The separate analysis for positive and negative feedback shows no correlation between the IP and the stability attribution within the positive feedback condition (r = − .14, p = .200). In contrast, there is a correlation between the IP and the stability attribution within the negative feedback condition (r = .27, p = .012). The fixed mindset expression also correlates positively with the IPP total score (r = .28, p < .001; H5).

Consistent with H3, the IP significantly moderates the effect of feedback on the locus of causality (B = -0.308, SE = 0.061, t = -5.071, p < .001, 95% CI [-0.43, -0.19]). The IP expression affected the locus of causality at high (B = -4.799, SE = 1.425, t = -3.367, p < .001, 95% CI = [-7.61, -1.99]) and low (B = 5.445, SE = 1.421, t = 3.832, p <. 001, 95% CI = [2.64, 8.25]) levels only, but not at a moderate level (B = 0.323, SE = 1.003, t = 0.322, p = .748, 95% CI = [-1.66, 2.30]). The interaction term significantly explained additional variance to the overall model (ΔR2 = 0.133, p < .001; Table 3). As shown in Fig. 1, a high IP expression is positively associated with the internal attribution of failure and negatively associated with the internal attribution of success. A low IP level is negatively associated with the internal attribution of success and positively associated with the internal attribution of failure.

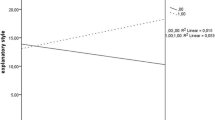

Consistent with H4, the impostor expression significantly moderates the effect of feedback on the stability attribution (B = -0.171, SE = 0.061, t = -2.804, p = .006, 95% CI = [-0.29, -0.05]). Examination of the conditional effects indicated that the IP is only associated with the stability attribution at a low (B = 4.444, SE = 1.425, t = 3.118, p = .002, 95% CI = [1.63, 7.26]), but not a moderate (B = 1. 604, SE = 1.006, t = 1.595, p = .113, 95% CI = [-0.38, 3.59]) and a high (B = -1.237, SE = 1.429, t = -0.865, p = .388, 95% CI = [-4.06, 1.58]) level. The interaction term significantly explained additional variance to the overall model (ΔR2 = 0.044, p = .006; Table 4). As shown in Fig. 2, a low IP expression is negatively related to the stable attributions of failure and positively related to the stable attribution for success. A moderate IP expression shows no significant moderating effect. Also high IP shows no significant moderating effect, but a tendency towards a more stable attribution with negative feedback and less stable attribution with positive feedback (Fig. 2).

Discussion

This article examined the IP’s role as a moderator between performance feedback and attribution and the IP’s relationship to the mindset. The moderation analyses show that the IP moderates the effect of performance feedback on the attribution dimensions causality and stability in the hypothesized way. A significant interaction effect of the IP and the feedback condition on locus of causality could be determined. According to this, impostors tend to internalize failure and externalize success. Therefore, it could be argued that the lower internalization of success is a main reason for the lower self-efficacy and increased external locus of control among Impostors despite success (Chae et al., 1995; Vergauwe et al., 2016). The interaction effect between the feedback and the IP expression concerning the stability dimension was also significant but less explicit than between the IP and locus of causality. Moderately and strong IP tendencies do not lead to an increased stability attribution of success. On the contrary, people with low IP show a self-esteem distortion in that they attribute success as more stable than failure. However, a trend can be observed that impostors tend to attribute failure as more stable and success less stable. This pessimistic stability perception regarding performance could partially drive the fear of failure and self-doubt despite success in impostors (Sakulku & Alexander, 2011).

These experimental results correspond with the psychometrical results regarding impostors’ attributional style (Ibrahim et al., 2021). Therefore, Impostors are characterized by an external-instable attribution of success and an internal-stable attribution of failure. This non-self-serving bias could be the main reason for impostors showing less self-esteem and more anxiety (Chrisman et al., 1995).

Due to the positive relationship between the fixed mindset and the IP, impostors seem to believe to some degree that intelligence is a fixed attribute (Kumar & Jagacinski, 2006). The connection with a fixed mindset also sheds new light on the impostor’s performance orientation. It suggests that impostors tend to have performance goal orientations, which means they prioritize displaying skills as more important than developing them through challenges (Yeager & Dweck, 2012). It further suggests that impostors, similar to people with a fixed mindset, exhibit an avoidance-based achievement motivation, which manifests in higher tendencies for impression-management as reported previously (Leary et al., 2000). Therefore, the belief that intelligence and abilities are unchangeable could be a major cause of impostors’ increased fear of failure. From the fixed mindset perspective, failure means that one is not intelligent enough and that this lack of intelligence is not changeable. Failure, therefore, always offers a risk of a negative and definite label. Therefore, this implicit belief would also explain why impostors avoid competitive situations (Ross & Krukowski, 2003), which carry the risk of revealing this lack of intelligence. The implicit belief in the immutability of intelligence and the existing self-doubt thus lead to helplessness (Morris & Tiggemann, 2013), as impostors fear that they are not intelligent and that others will find that out. The doubt about one’s abilities and the conviction that one cannot change these abilities explains the non-self-serving attributional bias. In this regard, successes cannot result from one’s abilities and cannot be a sign of one’s increasing ability because these are seen as fixed. The implicit theory of intelligence could be an essential mechanism for developing impostor feelings. It could also be an essential lever for reducing impostor feelings since the mindset can be changed through learning experiences (Plaks & Stecher, 2007), as indicated in the intervention study by Zanchetta et al. (2020). However, the relationship between mindset and IP needs to be further investigated in future research, as the relationship was only moderate in this study.

Limitations

First, the cross-sectional study design does not allow conclusions about causality. A longitudinal study would allow further insights into the direction of the predictor and the criterion variable, especially regarding the assumed influences of mindset on the IP in this study. Additionally, the survey was conducted online, which allows for less control of environmental factors. Furthermore, it should be noted that the initial presentation of the bogus construct as a stable personality trait may have increased the fixed mindset expression in candidates (Sarrasin et al., 2018). In addition, the internal attribution of the participants might be increased for positive and negative feedback, as the bogus construct has been described as a stable personality trait.

Second, the study used quantitative data. In future research, qualitative data could be used to investigate attributions and implicit theories of intelligence in more depth. In addition, the sample consisted exclusively of German participants and mainly students, so the generalisability is limited. In addition, the results on the non-self-serving attributional bias must be considered in the context of previous research results, as this study is the first to find this effect. The previous studies (e.g., Thompson et al., 2000) did not find the external-instable attributional bias in success, so the findings must be replicated in future studies.

Lastly, future research could include actual performance in achievement tasks as a control variable to account for intentionally reduced effort as a performance-avoidance strategy (Burnette et al., 2013) and gain insights into the influence of the IP and mindset on performance.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations, this experimental study demonstrates the non-self-serving bias in impostors for the first time (as far as the authors know). This bias is characterized by an internal locus of causality for failure, an external locus of causality for success, a reduced stability attribution for success, and an increased stability attribution for failure. Furthermore, the IP is positively related to the fixed mindset as the implicit entity theory of intelligence. Considering mindset as an influencing factor enables a practical interventional possibility to reduce fear of failure, the non-self-serving attributional bias, and the impostor feelings in general.

References

Brauer, K., & Wolf, A. (2016). Validation of the German-language Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (GCIPS). Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.071

Burnette, J. L., O’Boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655–701. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029531

Chae, J. H., Piedmont, R. L., Estadt, B. K., & Wicks, R. J. (1995). Personological evaluation of Clance’s Impostor Phenomenon Scale in a Korean sample. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65(3), 468–485. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_7

Chrisman, S. M., Pieper, W. A., Clance, P. R., Holland, C. L., & Glickauf-Hughes, C. (1995). Validation of the Clance Imposter Phenomenon Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65(3), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_6

Clance, P. R. (1985). The imposter phenomenon: Overcoming the fear that haunts your success. Atlanta, GA: Peachtree.

Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory research & practice, 15(3), 241. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0086006

Clance, P. R., & O’Toole, M. A. (1987). The imposter phenomenon: An internal barrier to empowerment and achievement. Women & Therapy, 6(3), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015V06N03_05

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Cozzarelli, C., & Major, B. (1990). Exploring the validity of the impostor phenomenon. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(4), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1990.9.4.401

Dinger, F. C., Dickhäuser, O., Spinath, B., & Steinmayr, R. (2013). Antecedents and consequences of students’ achievement goals: A mediation analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 28, 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.09.005

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Random House.

Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C., & Hong, Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A word from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0604_1

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618804166

Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.5

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. C., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Ferrari, J. R., & Thompson, T. (2006). Impostor fears: Links with self-presentational concerns and self-handicapping behaviours. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(2), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.07.012

Fried-Buchalter, S. (1992). Fear of success, fear of failure, and the imposter phenomenon: A factor analytic approach to convergent and discriminant validity. Journal of Personality Assessment, 58(2), 368–379. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5802_13

Ibrahim, F., Münscher, J. C., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2020). The facets of an impostor–development and validation of the impostor-profile (IPP31) for measuring impostor phenomenon. Current Psychology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00895-x

Ibrahim, F., Münscher, J. C., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2021). Examining the Impostor-Profile—Is there a general impostor characteristic? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 720072. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.720072

Kersting, M., Althoff, K., & Jäger, A. O. (2008). WIT-2. Der Wilde-Intelligenztest. Verfahrenshinweise. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

King, R. B. (2017). A fixed mindset leads to negative affect: the relations between implicit theories of intelligence and subjective well-being. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 225(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000290

Kolligian, J. Jr., & Sternberg, R. J. (1991). Perceived fraudulence in young adults: Is there an’Imposter syndrome’? Journal of personality assessment, 56(2), 308–326.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Kumar, S., & Jagacinski, C. M. (2006). Imposters have goals too: The imposter phenomenon and its relationship to achievement goal theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(1), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.05.014

Leary, M. R., Patton, K. M., Orlando, A. E., & Funk, W., W (2000). The Impostor Phenomenon: Self-Perceptions, Reflected Appraisals, and Interpersonal Strategies. Journal of Personality, 68(4), 725–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00114

Licht, B. G., & Dweck, C. S. (1984). Determinants of academic achievement: The interaction of children’s achievement orientations with skill area. Developmental Psychology, 20(4), 628–636. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.20.4.628

Mak, K. K. L., Kleitman, S., & Abbott, M. J. (2019). Impostor phenomenon measurement scales: a systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 671. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00671

Mangels, J. A., Butterfield, B., Lamb, J., Good, C., & Dweck, C. S. (2006). Why do beliefs about intelligence influence learning success? A social cognitive neuroscience model. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 1(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsl013

McAuley, E., Duncan, T. E., & Russell, D. W. (1992). Measuring causal attributions: The Revised Causal Dimension Scale (CDSII). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(5), 566–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167292185006

McGregor, L. N., Gee, D. E., & Posey, K. E. (2008). I feel like a fraud and it depresses me: The relation between the imposter phenomenon and depression. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 36(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2008.36.1.43

Miele, D. B., Son, L. K., & Metcalfe, J. (2013). Children’s naive theories of intelligence influence their metacognitive judgments. Child Development, 84(6), 1879–1886. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12101

Morris, M., & Tiggemann, M. (2013). The impact of attributions on academic performance; A test of the reformulated learned helplessness model. Social Sciences Directory, 2(2), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.7563/SSD_02_02_01

Pannhausen, S., Klug, K., & Rohrmann, S. (2020). Never good enough: The relation between the impostor phenomenon and multidimensional perfectionism. Current Psychology, 888–901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00613-7

Plaks, J. E., & Stecher, K. (2007). Unexpected improvement, decline, and stasis: A prediction confidence perspective on achievement success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(4), 667–684.

R Core Team (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 3.6.3) [Computer Software]. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/

Robins, R. W., & Pals, J. L. (2002). Implicit self-theories in the academic domain: Implications for goal orientation, attributions, affect, and self-esteem change. Self and identity, 1(4), 313–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860290106805

Ross, S. R., & Krukowski, R. A. (2003). The imposter phenomenon and maladaptive personality: Type and trait characteristics. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(3), 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00067-3

Sakulku, J. (2011). The impostor phenomenon. International Journal of Behavioral Science, 1(6), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.14456/ijbs.2011.6

Sarrasin, J. B., Nenciovici, L., Foisy, L. M. B., Allaire-Duquette, G., Riopel, M., & Masson, S. (2018). Effects of teaching the concept of neuroplasticity to induce a growth mindset on motivation, achievement, and brain activity: A meta-analysis. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 12, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2018.07.003

Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Learned optimism: How to change your mind and your life. Vintage Books a Division of Random House.

Thompson, T. (1994). Self-worth Protection: Review and implications for the classroom. Educational Review, 46(3), 259–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191940460304

Thompson, T., Davis, H., & Davidson, J. (1998). Attributional and affective responses of impostors to academic success and failure outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 25(2), 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00065-8

Thompson, T., Foreman, P., & Martin, F. (2000). Impostor fears and perfectionistic concern over mistakes. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(4), 629–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00218-4

Vergauwe, J., Wille, B., Feys, M., De Fruyt, F., & Anseel, F. (2015). Fear of being exposed: The trait-relatedness of the impostor phenomenon and its relevance in the work context. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(3), 565?581.

Whitman, M. V., & Shanine, K. K. (2012). Revisiting the Impostor Phenomenon: How Individuals Cope with Feelings of Being in Over their Heads. In P. L. Perrewé, J. R. B. Halbesleben, & C. C. Rosen (Hrsg.), The Role of the Economic Crisis on Occupational Stress and Well Being (Bd. 10, S. 177–212). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3555(2012)0000010009

Villwock, J. A., Sobin, L. B., Koester, L. A., & Harris, T. M. (2016). Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: A pilot study. International Journal of Medical Education, 7, 364–369. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5801.eac4

Want, J., & Kleitman, S. (2006). Imposter phenomenon and self-handicapping: Links with parenting styles and self-confidence. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(5), 961–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.10.005

Weiner, B. (2001). Intrapersonal and interpersonal theories of motivation from an attribution perspective. In Student motivation (S. 17–30). Springer.

Whitman, M. V., & Shanine, K. K. (2012). Revisiting the impostor phenomenon: How individuals cope with feelings of being in over their heads. Research in Occupational Stress and Well-being, 10, 177–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3555(2012)0000010009

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets That Promote Resilience: When Students Believe That Personal Characteristics Can Be Developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.722805

Zanchetta, M., Junker, S., Wolf, A. M., & Traut-Mattausch, E. (2020). Overcoming the fear that haunts your success – The effectiveness of interventions for reducing the impostor phenomenon. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 405. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00405

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fabio Ibrahim: Writing – Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization. Dana Göddertz – Conceptualization, Writing, Methodology, Investigation, Review & Editing. Philipp Yorck Herzberg – Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

On representative of all authors, the corresponding author declares that there is no conflict of interest. The study met the ethical standards for psychological research. No subject was adversely affected by participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Fabio Ibrahim and Dana Göddertz contributed equally.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibrahim, F., Göddertz, D. & Herzberg, P.Y. An experimental study of the non-self-serving attributional bias within the impostor phenomenon and its relation to the fixed mindset. Curr Psychol 42, 26440–26449 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03486-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03486-0