Abstract

This study aimed to examine the relationship between information overload and individual state anxiety in the period of regular epidemic prevention and control and mediating effect of risk perception and positive coping styles. Further, we explored the moderating role of resilience. 847 Chinese participated in and completed measures of information overload, risk perception, positive coping styles, state anxiety, and resilience. The results of the analysis showed that information overload significantly predicted the level of individual state anxiety (β = 0.27, p < 0.001). Risk perception partially mediate the relationship between information overload and state anxiety (B = 0.08, 95%CI = [0.05, 0.11]) and positive coping styles also partially mediate the relationship between information overload and state anxiety(B = -0.14, 95%CI = [-0.18, -0.10]). In addition, resilience moderated the mediating effects of risk perception (β = -0.07, p < 0.05) and positive coping styles (β = -0.19, p < 0.001). Resilience also moderated the effect of information overload on state anxiety (β = -0.13, p < 0.001). These results offer positive significance for understanding the internal mechanism of the influence of information overload on individual state anxiety in the epidemic environment and shed light on how to reduce people’s state anxiety during an epidemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 has caused the world to face a major health and safety crisis. The epidemic not only threatens people's physical health, causing various physical symptoms, sequelae, and even death (Lang et al., 2020; Odone et al., 2020; Speth et al., 2020); it also has a huge impact on individual mental health, such as anxiety and depression (Aboul-ata & Qonsua, 2022; Chen et al., 2021; Choi et al., 2020; Yue et al., 2020). This is not only because of the epidemic itself, but also because of the overwhelming information given during the epidemic (Catedrilla et al., 2020; Gallotti et al., 2020; Patel et al., 2020; Patwa et al., 2021). According to Dr. Sylvie Briand, Director of Global Infectious Disease Preparedness at WHO, the outbreak of COVID-19 was accompanied by an outbreak of an "infodemic." An “infodemic” is when too much information makes it difficult to find trustworthy sources of information, reliable guidance, and this information may even be harmful to people’s health. Therefore, information overload is one of the most important features of an "infodemic" (Farooq et al., 2020; Wang, 2020).

According to documents issued by the State Council of China, China has entered the period of regular epidemic prevention and control since April 49, 2020 (China, 2020). The regular epidemic prevention and control of the COVID-19 refers to: in order to cope with the persistence and long-term nature of epidemic prevention and control, certain emergency measures are transformed into sustainable and long-term prevention and control measures(Dong et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2021; Yu & Zheng, 2020). Therefore, during the period of regular epidemic prevention and control, epidemic prevention and control measures have become part of everyone's life (for example, individual must show health QR code when entering public places; individual should minimize unnecessary travel, reduce crowd gatherings and insist on going out wearing a respirator). During this period the epidemic has not completely disappeared and may break out at any time. A large number of intensive and indistinguishable health information or epidemic prevention needs that are closely related to health, work, and travel, caused by frequent epidemics often make individuals feel pressured and troubled (Burtscher et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021).

Reviewing the previous literature, we found that most of the research on health-related information overload focuses on the context of chronic diseases (Brittani et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2014; Liu & Kuo, 2016), and few studies are on information overload in public health emergencies. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, scholars have mostly explored information overload and other issues from the perspective of information science to examine the impact of information overload on individual behavior and physical and mental states (Ahmed, 2020; Hong & Kim, 2020; Mohammed et al., 2021; Valika et al., 2020). Little is known about the interaction between information overload and individual factors, and their underlying mechanisms. In addition, as far as the current epidemic situation is concerned, it is difficult for COVID-19 to end in a short period of time, so we are likely to face a long-term battle against COVID-19. It is very likely that we will be in a period of regular prevention and control of COVID-19 for a long time to come. Therefore, this study further explored the impact of epidemic information overload on individual state anxiety from the perspective of psychology and examined its internal psychological mechanism in the period of regular epidemic prevention and control to provide theoretical guidance and empirical evidence to reduce the negative impact of excessive information in the epidemic.

Information overload is often thought of as a state that occurs when decision makers face more information than they can handle (Jacob et al., 1974; Meyer, 1998). Lang (2000) integrated the perspectives of cognitive psychology and media research and proposed a limited capacity model of motivated mediated message processing (LC4MP). This model assumes that individual processors with limited capacity can process and store information from various media. Cognitive resources are automatically and continuously allocated. As a result, an excess of information can leave an individual feeling stressed, overloaded, out of control of the situation, and overwhelmed (Bawden & Robinson, 2009; Lang, 2000; Lee et al., 2016; Misra & Stokols, 2011; Phillips-Wren & Adya, 2020). This not only reduces the efficiency of obtaining information and the quality of decision-making (Pero et al., 2010), but is also harmful to the physical and mental health of individuals (Matthes et al., 2020), which in turn will lead to problems such as anxiety, depression, and social fatigue (Guo et al., 2020; Hwang et al., 2020; Primack et al., 2017). Since the outbreak of COVID-19 and the raging of the information epidemic, various social problems caused by information overload have aroused widespread concern among scholars. Some studies have shown that excessive information in the epidemic will cause individuals to be anxious about relevant information and even produce avoidance behaviors (Soroya et al., 2021). Other studies have confirmed that the information overload that individuals perceive during the epidemic has heightened their fears about COVID-19, triggering more negative emotions (Liu et al., 2021). A large amount of epidemic information not only prevents people from making correct protection decisions in a timely and effective manner (Laato et al., 2020), but also increases cognitive load and psychological pressure (Bermes, 2021; Islam et al., 2020; Tzafilkou et al., 2021).

Anxiety is a complex emotional state accompanied by physical arousal and feelings of fear, tension, annoyance, and worry (Spielberger, 2010). Spielberger divides anxiety into trait anxiety and state anxiety (Spielberger, 1966). Trait anxiety is regarded as a relatively stable personality trait that makes individuals more likely to perceive some non-dangerous situations as threatening, or produce more intense anxiety reactions. State anxiety is defined as a subjectively felt tension, an individual experience of anxiety in a specific situation (Spielberger, 1972), of which its degree fluctuates greatly with the situation (Leal et al., 2017; Ren, 2020; Tang & Gibson, 2005). Wurman, the father of information architecture, believed that when the amount of information acquired exceeds the information processing capacity, the excess will accumulate, causing stress and overstimulation, and eventually anxiety (Wurman et al., 2001). The anxiety caused by excess information in public health emergencies is a type of state anxiety, which is affected by specific situations (Bareket-Bojmel et al., 2020; Mallett et al., 2021; Ren et al., 2020). Therefore, this study mainly focused on the state anxiety of individuals exposed to excessive epidemic information and hypothesized that information overload would positively predict the level of individual state anxiety (Hypothesis 1).

Risk perception is considered individuals’ estimation and judgment of dangerous events based on their own intuition (Slovic, 1987). Research shows that information overload can cause individuals to experience uncertainty, overload, and stress (Aldoory & Van Dyke, 2006; Bawden & Robinson, 2009; Chowdhury et al., 2011; Shenk, 1997). Slovic was the first to apply the psychometric paradigm to the measurement of risk perception. On the basis of a large number of experimental data, he proposed “cognitive maps” of risk perceptions. He believed that uncertainty is an important indicator for evaluating an individual's risk perception state (Johnson & Slovic, 1995; Slovic, 1987), and that the growth of uncertainty leads to an increase in risk perception (Hien & Tsunemi, 2018; Li et al., 2021). Stress is also considered to be an important factor affecting the level of personal risk perception, and the perceived risk of individuals in stressful situations is higher (Sobkow et al., 2016; Traczyk et al., 2015). In addition, the social amplification of risk framework (Kasperson et al., 1988) also points out that the communication and dissemination of information on social media is an important factor leading to an increase in risk perception. Therefore, excessive epidemic information may strengthen an individual's risk perception of the epidemic. However, some scholars have proposed that risk perception includes an individual's evaluation process for the risk event (Cutter, 1993), while the cognitive theory of emotion states that emotion originates from an individual's cognitive evaluation of environmental stimuli (Lazarus et al., 1970). In addition, the level of risk perceived by an individual is closely related to their emotional response (Loewenstein et al., 2001). Research in the field of clinical science and psychology has shown that anxiety, fear, and other negative emotions are the direct responses of individuals after perceiving risks (Leppin & Aro, 2009; Slovic et al., 2004), and an increase in risk perception will lead to increased anxiety (Liu et al., 2020; Ng et al., 2017). The latest research also shows that the risk perception of pregnant women during the COVID-19 epidemic can predict their state anxiety levels (Lee et al., 2021). Accordingly, this study hypothesized that risk perception would be an important mediating variable between information overload and individual state anxiety during an epidemic (Hypothesis 2).

Coping is an individual's cognitive and behavioral efforts to mitigate the negative effects of the environment, while coping styles are the coping strategies adopted by individuals to face the environment (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). According to the common characteristics of different coping styles, they can be divided into two dimensions: positive and negative. Positive coping styles are more mature, usually includes problem solving, seeking help, and cognitive adjustment, similar to problem-oriented coping styles, while negative coping styles are relatively less mature, and include self-blame, avoidance, and fantasies, and are similar to emotion-oriented coping (Folkman & Lazarus, 1986; Xie, 1998). Many researchers believe that information overload directly creates a stressful experience (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; Jacob et al., 1974; Malhotra, 1982). The cognitive phenomenological transactional theory of stress indicates that coping style, as an individual factor, is an important mediator between stressful events and outcomes (Lazarus & Launier, 1978). Existing studies have confirmed that in stressful situations, the greater the stress an individual is under, the less positive coping styles are used (Chen et al., 2020; Wang & Wang, 2019). In turn, the less positive coping styles are used, the higher the anxiety level will be (Long et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2020). Therefore, we hypothesized that positive coping styles would mediate the relationship between information overload and state anxiety (Hypothesis 3).

The influx of information can lead to information overload, which can lead to negative psychological and behavioral reactions and anxiety in individuals (Soroya et al., 2021). Resilience, as a protective factor for anxiety, can effectively alleviate the anxiety symptoms of individuals in stressful situations caused by information overload (Xu et al., 2021). Some studies believe that an interactive effect exists between stressful events and resilience (Lu et al., 2016; Sojo & Guarino, 2011). Individuals with higher resilience experience less impact on their own mental health due to perceived stress (Lu et al., 2016). New research finds that individual resilience during COVID-19 can significantly reduce the negative effects of information overload and disinformation (Bermes, 2021). Therefore, we hypothesized that resilience might moderate the effect of information overload on state anxiety (Hypothesis 4). Studies have shown that personal characteristics are an important factor affecting risk perception (Bouyer et al., 2010; Wildavsky & Dake, 1990). Endler proposed a multidimensional interaction model, arguing that the interaction of individual factors and situational variables affects an individual's perception of risk (Endler & Kocovski, 2001). However, as an important personal quality for individuals to cope with adverse environmental factors (Xi et al., 2008; Yu & Zhang, 2007), the mechanisms of resilience between information overload and risk perception are still inconclusive. Whether resilience can be used as a protective factor to alleviate the impact of information overload on individual risk perception remains to be further investigated. Accordingly, we hypothesized that resilience would moderate the effect of information overload on risk perception (Hypothesis 5). In addition, some scholars have proposed that resilience is an ability that allows individuals to cope with stress in a healthier way to achieve their goals (Epstein & Krasner, 2013). Individuals with higher resilience are more inclined to adopt positive coping methods (Konaszewski et al., 2021). Therefore, we hypothesized that resilience might also be an important moderator between information overload and positive coping styles (Hypothesis 6). In sum, this study proposed a moderated multiple mediation model (see Fig. 1) to explore the relationship between research variables.

Methods

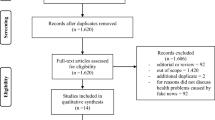

Participants

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University. In this study, a simple random convenience sampling method was used. The participants came from 29 provinces across the country, and 921 questionnaires were distributed. Sixty-nine invalid questionnaires (not serious, missed, and regular) were excluded. In addition, five participants had at least one standardized score in the item measure higher than 3.29 or lower than -3.29, and were, therefore, considered outliers to be removed as suggested by the recommendations of Tabachnick and Fidell (Tabachnick et al. 2007). Finally, 847 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective rate of 91.97%. Among them were 349 men (41.20%) and 498 women (58.80%). The participants were aged between 18 and 53 years (M = 29.10; SD = 8.67). At the time of our data collection, 17 of these 29 provinces had several medium-risk areas within a month at the time of data collection (medium-risk areas are defined as areas with new COVID-19 infections within 14 days, however, the cumulative number of confirmed cases does not exceed 50, or the cumulative number of COVID-19 infections in the region exceeds 50, and no cluster epidemic has occurred within 14 days), and 6 provinces have one to several high-risk areas within one month (high-risk areas refer to areas with more than 50 cases of COVID-19 infection in the area and a cluster of outbreaks within 14 days). The survey of their epidemic experience showed that 76 participants (8.97%) have experienced isolation in the past six months (there are two ways of isolation in China, one is centralized isolation: living in a uniformly arranged independent isolation building, a single room is not allowed to go out, and staff in protective clothing will deliver meals and measure body temperature. The second is home isolation: under the guidance of community medical staff, live alone, cannot go out, and monitor body temperature and symptoms. There were 31 participants (3.66%) in the community, street, or village where someone had contracted COVID-19 in the past six months. In addition, we used the form of multiple-choice questions to ask the participants to report what kind of the information media he used frequently. 633 participants (64.70%) reported that the Internet was one of their frequently used information media. 479 participants (56.60%) believed that friends and colleagues were also important sources for them to obtain information related to the epidemic. 473 participants (55.80%) reported they got news from their family members. 455 participants (53.70%) also considered television as one of the sources of epidemic-related information.

Measures

Information overload

The Information Overload Severity Scale in COVID-19 was used (Yang et al., 2021) to measure the information overload of individuals at the period of regular epidemic prevention and control. The scale has a total of seven items, for example: “You received more information about the COVID-19 than you can handle”, and “Recently, you have received a lot of information related to the COVID-19 from different information media, which makes you feel stressed”. A 5-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (always). A higher total score indicates a higher severity of information overload. The scale is suitable for all age groups in China and has good reliability and validity (Yang et al., 2021). Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.95.

Risk perception

Using the COVID-19 Perceived Risk Scale compiled by Yıldırım and Güler (Yıldırım & Güler, 2020), this study used back-translation to translate the original English version of the scale. Psychologists first translated the scale into Chinese and then invited foreign language students to translate into English, and then 13 psychology professionals collectively discussed the final Chinese version of the COVID-19 Perceived Risk Scale. There were eight items in total, for example: “Perceived likelihood of acquiring COVID-19″, and “Worry about a family member contracting COVID-19″. Considering the language habits of different cultures, the Item 8 has been slightly modified. The English literal translation was "Worry about COVID-19 emerging as a health issue,” and the Chinese version was changed to "Worry about COVID-19 emerging as a health threat.” We used a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (negligible) to 5 (very large). A higher total score indicated a higher perceived risk of COVID-19. A confirmatory factor analysis showed that the scale had good construct validity (CMIN/DF = 4.80, RMSEA = 0.067, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.96, GFI = 0.98, NFI = 0.98). The Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.88.

Positive coping styles

The Positive Coping Styles subscale of the Simplified Coping Styles Questionnaire compiled by Xie (Xie, 1998) was used, with a total of 12 items, for example: “Try to see the bright side of things”, and “Ask relatives, friends or classmates for advice”. A 4-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 0 (not used) to 3 (frequently used). Higher scores indicate that individuals are more inclined to adopt positive coping styles. The scale is suitable for all age groups in China and has good reliability and validity (Xia et al., 2020; Xu & Fu, 2018). The Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.81.

State anxiety

The State Anxiety Inventory (SAI) developed by Spielberger (1983) revised by Wang et al. (1999) was used to assess an individual's state anxiety level. The scale consists of 20 items, for example: “I felt anxious”, and “I was nervous”. A 4-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very obvious). A higher total score indicates a higher level of state anxiety. Items 2, 5, 8, 10, 11, 15, 16, 19, and 20 are reverse-scored. The scale is suitable for all age groups in China and has good reliability and validity (Li & Wu, 2016; Liu & Wang, 2017). Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.83.

Resilience

The study used the Chinese version of the Resilience Scale (Conner-Davidson Resilience Scale, CD-RISC) revised by Yu and Zhang (2007). There were 25 items in total, for example: “I know where to go for help”, and “Under pressure, I am able to focus and think clearly”. A 5-point Likert scale was used, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always), and the total score is the score of resilience. The higher the total score, the higher the resilience. The scale is suitable for all age groups in China and has good reliability and validity (Huang et al., 2016; Liu & Kuo, 2016). Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.97.

Data analysis

SPSS 24.0 and the Process 3.4 macro program were used to carry out descriptive statistical analysis, correlation analysis, and moderated mediation effect test on the data. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed using Amos 24.0.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Since data were collected using a self-reported method, the results may be affected by common method bias, so Harman's one-factor test was used to test for common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003), and the total eigenvalues greater than 1 were obtained without rotation; there were 13 common factors, and the explanation rate of the first common factor was 21.13%, which was much lower than 40%. Therefore, there was no serious common method bias in this study.

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis results for each study variable. Information overload was significantly positively correlated with state anxiety, risk perception, and positive coping styles, risk perception was significantly positively correlated with state anxiety, and positive coping styles were significantly negatively correlated with state anxiety. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

In this study, 76 participants experienced isolation in the past six months. The risk perception level of participants with isolation experience was significantly higher than that of the other 771 participants (t = 4.80, p < 0.001), and the state anxiety level of the participants who had experienced isolation was also significantly higher than that of the other 771 participants (t = 4.00, p < 0.001). In addition, 31 participants resided in the community, street, or village where someone had contracted COVID-19 in the past six months. The risk perception of these 31 participants (t = 4.56, p < 0.001) and state anxiety (t = 3.07, p < 0.01) were also significantly higher than the remaining 816 participants. In the analysis that follows, these two variables enter the equation as control variables.

Mediation model

The study used Model 4 in the Process 3.4 macro of SPSS 24.0 (Hayes, 2013) with 5000 bootstrap samples. Considering the correlation between gender, age, and individual state anxiety in previous studies (Li & Lopez, 2010; Wenjing et al., 2019), in addition, considering whether there is a history of isolation, and whether anyone has been living in the same community, street, or village with participants having ever contracted COVID-19 has an impact on the research variables, gender, and age. This was regardless of whether there has been isolation experience, and whether there has been anyone living in the same community, street, or village with participants having ever contracted COVID-19 were included in the control variables. The results showed (see Table 2) that information overload had a significant predictive effect on state anxiety (β = 0.27, p < 0.001). When risk perception and positive coping styles were introduced as mediating variables, the predictive effect of information overload on state anxiety was still significant (β = 0.33, p < 0.001), and information overload had a significant positive predictive effect on risk perception (β = 0.36, p < 0.001), and risk perception positively predicted state anxiety (β = 0.22, p < 0.001). The results of the mediation test of risk perception (see Table 3) showed that its 95% confidence interval was [0.05, 0.11], indicating that risk perception mediates the effect of information overload on state anxiety, and the mediating effect was 0.08, accounting for the total effect of 28.57%. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. In addition, in this model, information overload had a significant predictive effect on positive coping styles (β = 0.44, p < 0.001), and positive coping styles could also significantly negatively predict state anxiety (β = -0.31, p < 0.001). The results of the mediation test of positive coping styles (see Table 3) showed that its 95% confidence interval was [-0.18, -0.10], indicating that positive coping styles mediate the effect of information overload on state anxiety, and the mediating effect was -0.14, accounting for 50.00% of the total effect, Hypothesis 3 was supported. It should be noted here that the direct effect was positive, while the mediating effect of positive coping styles was negative, indicating that there was a suppressing effects (MacKinnon, 2012).

Moderated multiple mediation model

To explore the moderating effect of resilience, Model 8 in the Process macro developed by Hayes (2013) was used. The results showed that (see Table 4; Fig. 2) after controlling for demographic variables, the interaction between information overload and resilience has a significant impact on risk perception, positive coping styles and state anxiety (risk perception: β = -0.07, p < 0.05; positive coping styles: β = 0.19, p < 0.001; state anxiety: β = -0.13, p < 0.001). This suggests that resilience moderates the effects of information overload on risk perception, positive coping styles, and state anxiety; thus, Hypotheses 4, 5, and 6 were supported.

To further illustrate the moderating effect of resilience, a simple slope analysis was performed. Figure 3 shows that for participants with low mental resilience (M-SD), information overload significantly positively predicted state anxiety (simple slope = 0.46, p < 0.001), while for participants with high resilience (M + SD), information overload could also significantly positively predict state anxiety. However, its predictive effect was smaller (simple slope = 0.19, p < 0.001), which showed that with the improvement of individual resilience, the predictive effect of information overload on state anxiety gradually decreased.

Figure 4 shows that for participants with low resilience (M-SD), information overload significantly positively predicted risk perception (simple slope = 0.44, p < 0.001), while for participants with high resilience (M + SD), although information overload could also significantly positively predict risk perception, its predictive effect was small (simple slope = 0.30, p < 0.001), indicating that with the improvement of individual resilience, the impact of information overload on risk perception decreased significantly.

Figure 5 shows that for participants with low resilience (M-SD), information overload significantly predicted positive coping styles (simple slope = 0.18, p < 0.001), while for participants with high resilience (M + SD), the predictive effect of information overload on positive coping styles was greater (simple slope = 0.55, p < 0.001), indicating that with the improvement of individual resilience, the predictive effect of information overload on positive coping styles increased significantly.

Table 5 further illustrates the mediating effects of risk perception and positive coping styles under different levels of resilience. Specifically, with the increase in resilience, the mediating effect of risk perception decreased significantly, while the mediating effect of positive coping styles increased significantly.

Discussion

The results showed that information overload significantly predicted individual state anxiety levels; risk perception and positive coping styles played a partial mediating role between epidemic information overload and state anxiety, but information overload significantly positively predicted positive coping styles; risk perception and positive coping styles had a positive correlation. The mediating effect was moderated by resilience, which also moderated the effect of information overload on state anxiety. This study was conducted one and a half years after the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic in China, under the background of the "information age" and "fluctuating epidemic situation.” China is in the period of regular epidemic prevention and control. Although the overall morbidity and mortality of the COVID-19 in China are relatively low(Tan et al., 2021), the epidemic situation is still severe. First of all, in terms of the external environment, the COVID-19 is still spreading rapidly around the world. Second, there are often small-scale outbreaks in China, and the prevention and control of the epidemic cannot be slacken(Yu & Zheng, 2020). The experience of Chinese people in information processing and emotional level has not become easier. It can also be seen from the data of this study that the risk perception level of participants with isolation experience was significantly higher than that of the other participants. The risk perception and state anxiety of those who had a COVID-19 outbreak near their place of residence were also significantly higher than the remaining participants. Moreover, Taking the COVID-19 outbreak in Shanghai in 2022 as an example, there are tens of thousands of new infections every day. Officials are constantly releasing new epidemiological findings and updating epidemic prevention measures. People can read the overwhelming news related to the epidemic on the Internet and WeChat every day. This excessive information has brought enormous psychological pressure to individuals. As far as the current epidemic situation is concerned, China is likely to be in a period of regular prevention and control of the epidemic for a long time. Therefore, this study hopes to bring some enlightenment on how to improve the mental health of individuals alleviate the negative impact of information overload during the epidemic by studying the information overload, state anxiety, risk perception, positive coping style and psychological resilience of Chinese people. In addition, in this epidemic, China's national conditions and culture make the Chinese people's response to the epidemic very unique. China has adopted resolute city closure measures and isolation measures, closed nonessential businesses, and quickly built makeshift hospitals (Peng et al., 2020; Wang, 2020). The way people process and respond to information is also unique. The collectivist culture makes Chinese people more inclined to seek help from relatives and friends in times of epidemic(Xu et al., 2022). Therefore, all these conclusions need to be understood in the context of China's specific anti-epidemic situation and collectivist culture, tight culture, and high-power distance.

This study found that information overload could significantly predict state anxiety levels; that is, individuals with higher information overload scores had higher state anxiety levels. This is consistent with previous studies (Bawden & Robinson, 2020; Eppler, 2015; Renjith, 2017). The main explanations are as follows: First, according to the cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988), individuals will produce cognitive processing activities when they receive and process information. The contradiction between the information and the limited cognitive resources of people will produce contradictions, which will have a negative impact on the individual and bring about negative emotions such as anxiety. Second, uncertainty caused by information will lead to anxiety. A large amount of epidemic information is not only a kind of cognitive load, but also contains much content related to the epidemic, such as infection prevention strategies, vaccine effectiveness, the increase in the number of people, the regional blockade caused by the epidemic prevention requirements, and the related impact on for example work, travel, and study. (Ahmed, 2020; Fan & Smith, 2021; Honora et al., 2022), the pressure and various uncertainties they bring will lead to individual worries and anxiety (Aljanabi, 2021; Cao et al., 2021; Rathore & Farooq, 2020). Third, according to the theory of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks (Kramer et al., 2014), emotions can be transmitted and affect others through social relationship networks. Negative information about the COVID-19 epidemic on various media platforms contains negative emotions, which will be transmitted to the audience through the media, thereby aggravating the negative psychological reaction of the audience (Yeung et al., 2018).

The mediating effect of risk perception

The results showed that risk perception had a significant mediating effect between information overload and state anxiety; that is, information overload could not only directly affect the level of individual state anxiety, but also affected state anxiety through risk perception. This conclusion supports the social amplification of risk framework (Kasperson et al., 1988). Under the epidemic environment, the excess information about the epidemic in various media networks has greatly improved the public's risk perception level. In addition, the framework of the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) (Mehrabian & Russell, 1974) argues that environmental factors can influence individual responses e.g., anxiety (Zheng et al., 2020)) through organismal factors (e.g., risk perception (Li & Yuan, 2018)). Therefore, individuals with a low degree of information overload have less perceived uncertainty and severity about the COVID-19 epidemic, less perceived risk, and less state anxiety (Janssens et al., 2004); and individuals with a higher degree of information overload will have a stronger sense of uncertainty (Chowdhury et al., 2011), making them feel their safety is threatened, and their assessment of consequences will be more serious (Quan et al., 2020), resulting in a higher perception of the risk of the COVID-19 epidemic, and ultimately more seriously increasing the individual's anxiety.

The mediating effect of positive coping styles

This study found that information overload significantly positively predicted positive coping styles, which was consistent with the prediction effect proposed by Hypothesis 3 of this study, but in the opposite direction. Reviewing the existing literature, no research has directly examined the relationship between information overload and individual coping styles, but a large number of scholars believe that information overload will result in a sense of pressure (Bawden & Robinson, 2009; Misra & Stokols, 2011; Wurman et al., 2001). On this basis, this study expected that information overload would be negatively correlated with positive coping styles; however, the results showed that information overload was significantly positively related to positive coping styles. The possible reasons are as follows: First, Lazarus and Folkman (1984) hold that coping is the result of the interaction between individual and situational factors, and will change with the change in the situation. At present, China has entered the period of regular epidemic prevention and control. Although the COVID-19 epidemic has fluctuated over time, it is generally stable. In addition, the active intervention of the government, the active dissemination of relevant epidemic prevention knowledge by professionals, and the sufficient response resources brought about by extensive social support in disaster-stricken areas (Ye & Shen, 2002) also channel the masses to be more inclined to adopt active protection measures and coping strategies in the face of epidemic information overload (Dai et al., 2020; Duan et al., 2020). Second, according to the conservation of resources theory (COR), cultural value orientation is an important factor in coping with pressure (Hobfoll, 2001; Oyserman, 2017). Individuals with different value orientations tend to take different ways to deal with stress (Moos, 2002). In collectivist cultures, people tend to take the group as the core of the social unit, emphasize interpersonal relationships and the group identity of the self, and are more inclined to use the power of the collective to deal with stress (Geert & Hofstede, 1980; Kuo, 2013). They seek help from others more and learn from others' effective methods, so they score higher in positive coping styles in stressful situations. Third, information overload brings not only a sense of pressure, but also uncertainty (Gardikiotis et al., 2021; O'Reilly III, 1980; Phillips-Wren & Adya, 2020). The model of risk information seeking and processing (Griffin et al., 1999) believes that individuals in the risk events as a result of the uncertainty of risk events will actively collect relevant information about risk events and build their defensive attitudes, beliefs and behaviors to maintain their own health (Griffin et al., 1995). This behavior of actively reducing uncertainty to deal with risks corresponds to a positive problem-oriented coping style, which positively relates information overload to positive coping styles. In addition, this result also suggests that information overload is necessary to a certain extent in the period of regular epidemic prevention and control. When the epidemic first broke out, a large amount of epidemic information had more negative effects on people. The epidemic lasted for a year and a half. For a long time, people have gradually adapted and developed a new mode of processing information in the fight against the epidemic: people need to face a large amount of information, however, through active communication with others, obtaining more social support, and finding solutions, is a way to digest this information. This is consistent with the results of the mediation effect test: a positive coping style mediates the effect of information overload on state anxiety. In the information overload situation, individuals use more positive coping styles, which can reduce uncertainty (Yang et al., 2015) and ultimately reduce the level of individual state anxiety.

The moderating effect of resilience

The results of the study showed that, compared with individuals with high resilience, the information overload of individuals with low resilience had a more significant predictive effect on state anxiety. This conclusion can be explained by the diathesis-stress theory (Monroe & Simons, 1991), that is, the adverse impact of excess information about COVID-19 on individuals as external environmental events can be alleviated by inner diathesis resilience (Xi et al., 2008). Individuals with higher resilience are more tolerant of uncertainty (Cooke et al., 2013), and can better cope with the psychological pressure caused by information overload (Bermes, 2021), thereby protecting the mental health of the individual. In addition, studies have shown that individuals with high psychological resilience are not only good at and used to use positive emotions, but can also influence people around them to generate positive emotions and create a supportive social network (Kumpfer, 2002; Werner & Smith, 1992). These factors are all conducive to highly resilient individuals experiencing less anxiety. However, individuals with low resilience have a weaker emotional regulation ability when faced with the stressful situation of epidemic information overload (Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012; Mestre et al., 2017), and it is difficult to quickly recover from negative events (Tugade et al., 2004), thus, they have higher levels of state anxiety.

Second, resilience moderated the impact of information overload on risk perception. This further supports the multidimensional interaction model (Endler & Kocovski, 2001). The interaction between the individual factors of psychological resilience and information overload affects an individual's perception of danger. Individuals with high resilience have more psychological resources and stronger psychological adaptability (Ellis et al., 2011), can better cope with various pressures and unfavorable environments during the COVID-19 epidemic (Chitra & Karunanidhi, 2021; Li & Hasson, 2020; Tugade et al., 2004), and tend to perceive relatively low risks when facing risks (Chen et al., 2017). However, individuals with low resilience have fewer psychological resources and also find it difficult to deal with negative situations well (Cusinato et al., 2020), resulting in higher risk perception.

In addition, the study also found that resilience moderated the impact of information overload on positive coping styles. This is consistent with the conclusions of the protective factors model (Garmezy, 1985) and resilience framework (Kumpfer, 2002). As a protective factor for environmental risk factors, high resilience enables individuals to have stronger adaptability in adverse environments (Connor & Davidson, 2003), more psychological resources, such as optimism, tranquility (Pietrzak et al., 2009), and more coping resources (Ye & Shen, 2002). These individuals can effectively mobilize their own resources in the face of adverse environments and respond more proactively. In addition, the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions also points out that individuals with high resilience can increase their personal resources and adapt through positive emotions in the face of negative events (Fredrickson et al., 2003), which lead them to adopt more positive coping methods, and ultimately reduce their anxiety levels.

Implications

This study confirms the influence of information overload on individual state anxiety in the period of regular epidemic prevention and control, reveals the intermediate path of information overload of the COVID-19 epidemic triggering individual state anxiety, and answers the question of under which circumstances the mediating effects of risk perception and active coping styles will be more significant. The latter is of positive significance for understanding the internal mechanism of the influence of information overload on individual state anxiety in the epidemic environment. Second, the moderated multi-mediation model sheds light on how to reduce people’s state anxiety during an epidemic. At individual level, one can communicate more with relatives and friends, seek solace, and obtain more social support. At environmental level, it is also necessary for government departments to actively intervene, implement prevention and control measures, and ensure sufficient supplies, which are all conducive to protecting the psychological resilience of individuals during an epidemic. It helps people bridge the gap between perceived risk and actual risk, conduct effective risk communication, and adopt a more active coping style, thereby reducing anxiety.

The results of this research must also be considered in the context of the world and China’s anti-epidemic stance. The COVID-19 epidemic is very severe worldwide. The number of people infected with COVID-19, the number of deaths, and the percentage are very large, while the number of infections and deaths in China is very low. In this study, 3.66% of the participants whose community, street, or village where they lived in the past six months, suffered from COVID-19, which is a very low number. In contrast to the very loose control measures in some European and American countries (Uddin et al., 2020), China’s control measures are strict and efficient (China, 2020). Chinese people's perceptions of risk, information overload, and coping methods during the epidemic are closely related to these backgrounds, collectivist culture, and tight culture in China. A tight culture will bring more constraints and emphasize social norms. When a crisis occurs, it will make it easier for people to stay in step and overcome difficulties (Gelfand et al., 2011). Studies have shown that during this epidemic, people in countries with tight cultures will reduce the frequency of going to public places (Huynh, 2020). Of the participants, 8.97% experienced isolation in the past six months, which shows the strength of government control and people's willingness to cooperate. However, countries with a loose culture place more emphasis on individualism and tend to put freedom above security (Gelfand et al., 2011). All of these may have an impact on individuals' cognition, emotional responses, and coping behaviors during the COVID-19 epidemic.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations that provide directions for future research. First, this study used a self-report method to conduct a questionnaire survey, which may cause response bias, and a combination of self-report and others' evaluations could be used to collect data in the future. Second, although there is a theoretical basis for the investigation of relevant variables in the research design, it is difficult to reveal the profound causal relationship between variables by adopting a cross-sectional research design. The study was concluded one and a half years after the outbreak of the epidemic. As the COVID-19 epidemic situation changes, will human beings develop new ways of processing information and will their perception of epidemic risk change? Future longitudinal studies are required to validate and update our conclusions. Third, although participants in this study reported what kind of information media they commonly used to obtain epidemic-related information, there was no further investigation into which information media was the most consumed. This needs to be further explored in future research. In addition, this study only focused on the impact of information overload on individual state anxiety during the epidemic. Trait anxiety, as a relatively stable personality trait, is likely to cause individuals to have a stronger anxiety response in the same information overload situation (Spielberger, 1966), which can be included in future research to explore the overall impact of information overload on individuals more comprehensively. Finally, the conclusions of this study are directly related to the specificity of China in the COVID-19 epidemic. Are the conclusions of this study applicable to countries in loose and individualistic cultures? This will need to be verified in cross-cultural contexts in the future.

Conclusions

Information overload significantly predicts state anxiety. Risk perception and positive coping styles partially mediate the relationship between information overload and state anxiety. The mediating effects of risk perception and positive coping styles were moderated by resilience, which also moderated the effect of information overload on state anxiety.

References

Aboul-ata, M. A., & Qonsua, F. T. (2022). The 5-factor model of psychological response to COVID-19: Its correlation with anxiety and depression. Current Psychology, 41(1), 516–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01701-y

Ahmed, S. T. (2020). Managing News Overload (MNO): The COVID-19 Infodemic. Information, 11(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/info11080375

Aldoory, L., & Van Dyke, M. A. (2006). The roles of perceived “shared” involvement and information overload in understanding how audiences make meaning of news about bioterrorism. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(2), 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900608300208

Aljanabi, A. R. A. (2021). The impact of economic policy uncertainty, news framing and information overload on panic buying behavior in the time of COVID-19: A conceptual exploration. International Journal of Emerging Markets. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-10-2020-1181

Bareket-Bojmel, L., Shahar, G., & Margalit, M. (2020). COVID-19-Related Economic Anxiety Is As High as Health Anxiety: Findings from the USA, the UK, and Israel. Int J Cogn Ther, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41811-020-00078-3

Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2009). The dark side of information: Overload, anxiety and other paradoxes and pathologies. Journal of Information Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551508095781

Bawden, D., Robinson, L. (2020). Information overload: An overview. In Oxford encyclopedia of political decision making. Oxford University Press: Oxford, pp. 1–60.

Bermes, A. (2021). Information overload and fake news sharing: A transactional stress perspective exploring the mitigating role of consumers’ resilience during COVID-19. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102555

Bouyer, M., Bagdassarian, S., Chaabanne, S., & Mullet, E. (2010). Personality Correlates of Risk Perception. Risk Analysis an Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis, 21(3), 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/0272-4332.213125

Brittani, Crook, Keri, K., Stephens, Angie, E., Pastorek, Michael, & Mackert. (2015). Sharing Health Information and Influencing Behavioral Intentions: The Role of Health Literacy, Information Overload, and the Internet in the Diffusion of Healthy Heart Information. Health Communication, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.936336

Burtscher, J., Burtscher, M., & Millet, G. P. (2020). (Indoor) isolation, stress and physical inactivity: Vicious circles accelerated by Covid? Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13706

Cao, J., Liu, F., Shang, M., & Zhou, X. (2021). Toward street vending in post COVID-19 China: Social networking services information overload and switching intention. Technology in Society, 66, 101669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101669

Catedrilla, J., Limpin, L., Ebardo, R., Cuesta, J. D. L., & Trapero, H. A. (2020). Loneliness, Boredom and Information Anxiety on Problematic Use of Social Media during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 28th International Conference on Computers in Education,

Chen, J., Li, J., Cao, B., Wang, F., Luo, L., & Xu, J. (2020). Mediating effects of self-efficacy, coping, burnout, and social support between job stress and mental health among young Chinese nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(1), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14208

Chen, Y., Xu, H., Liu, C., Zhang, J., & Guo, C. (2021). Association Between Future Orientation and Anxiety in University Students During COVID-19 Outbreak: The Chain Mediating Role of Optimization in Primary-Secondary Control and Resilience. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.699388

Chen, Z., Han, D., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Research on the relationship between psychological resilience and risk perception level of nursing staff. Journal of Nursing Administration, 17(10), 3. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-315X.2017.10.005(InChinese)

China, S. C. I. O. o. t. P. s. R. o. (2020). Fighting Covid-19: China in action. People’s Publishing House

Chitra, T., & Karunanidhi, S. (2021). The impact of resilience training on occupational stress, resilience, job satisfaction, and psychological well-being of female police officers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 36(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9294-9

Choi, E. P. H., Hui, B. P. H., & Wan, E. Y. F. (2020). Depression and Anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103740

Chowdhury, S., Gibb, F., & Landoni, M. (2011). Uncertainty in information seeking and retrieval: A study in an academic environment. Information Processing & Management, 47(2), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2010.09.006

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

Cooke, G. P., Doust, J. A., & Steele, M. C. (2013). A survey of resilience, burnout, and tolerance of uncertainty in Australian general practice registrars. Bmc Medical Education, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-2

Cusinato, M., Iannattone, S., Spoto, A., Poli, M., Moretti, C., Gatta, M., & Miscioscia, M. (2020). Stress, resilience, and well-being in Italian children and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8297. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228297

Cutter, S. (1993). Living with risk. London: Edward Arnold.

Dai, B., Fu, D., Meng, G., Liu, B., Li, Q., & Liu, X. (2020). The effects of governmental and individual predictors on COVID-19 protective behaviors in China: A path analysis model. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 797–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13236

Dong, Q.-Q., Qiu, L.-R., Cheng, L.-M., Shu, S.-N., Chen, Y., Zhao, Y., Hao, Y., Shi, H., & Luo, X.-P. (2020). Kindergartens reopening in the period of regular epidemic prevention and control, benefitial or harmful? Current Medical Science, 40(5), 817–821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11596-020-2257-2

Duan, T., Jiang, H., Deng, X., Zhang, Q., & Wang, F. (2020). Government intervention, risk perception, and the adoption of protective action recommendations: Evidence from the COVID-19 prevention and control experience of China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103387

Ellis, B. J., Boyce, W. T., Belsky, J., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2011). Differential susceptibility to the environment: An evolutionary–neurodevelopmental theory. Development and psychopathology, 23(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000611

Endler, N. S., & Kocovski, N. L. (2001). State and trait anxiety revisited. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 15(3), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(01)00060-3

Eppler, M. J. (2015). 11. Information quality and information overload: The promises and perils of the information age. In Communication and technology (pp. 215–232). De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110271355-013

Eppler, M. J., & Mengis, J. (2004). Taylor & Francis Online : The Concept of Information Overload: A Review of Literature from Organization Science, Accounting, Marketing, MIS, and Related Disciplines - The Information Society - Volume 20, Issue 5. Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-9772-2_15

Epstein, R. M., & Krasner, M. S. (2013). Physician resilience: What it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Academic Medicine, 88(3), 301–303. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318280cff0

Fan, J., & Smith, A. P. (2021). Information Overload, Wellbeing and COVID-19: A Survey in China. Behavioral Sciences, 11(62), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11050062

Farooq, A., Laato, S., & Islam, A. N. (2020). Impact of online information on self-isolation intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(5), e19128. https://doi.org/10.2196/19128

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1986). Stress processes and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(2), 107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.95.2.107

Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365

Gallotti, R., Valle, F., Castaldo, N., Sacco, P., & Domenico, M. D. (2020). Assessing the risks of "infodemics" in response to COVID-19 epidemics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-00994-6

Gardikiotis, A., Malinaki, E., Charisiadis-Tsitlakidis, C., Protonotariou, A., & Zafeiriou, G. (2021). Emotional and Cognitive Responses to COVID-19 Information Overload under Lockdown Predict Media Attention and Risk Perceptions of COVID-19. Journal of Health Communication, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1949649

Garmezy, N. (1985). Stress-resistant children: The search for protective factors. Recent Research in Developmental Psychopathology, 4, 213–233.

Geert, & Hofstede. (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(80)90013-3

Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., Duan, L., Almaliach, A., Ang, S., & Arnadottir, J. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science, 332(6033), 1100–1104. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1197754

Griffin, R. J., Dunwoody, S., & Neuwirth, K. (1999). Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environmental Research, 80(2), S230–S245. https://doi.org/10.1006/enrs.1998.3940

Griffin, R. J., Neuwirth, K., & Dunwoody, S. (1995). Using the theory of reasoned action to examine the impact of health risk messages. Annals of the International Communication Association, 18(1), 201–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.1995.11678913

Guo, Y., Lu, Z., Kuang, H., & Wang, C. (2020). Information avoidance behavior on social network sites: Information irrelevance, overload, and the moderating role of time pressure. International Journal of Information Management, 52, 102067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102067

Hayes, A. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Journal of Educational Measurement, 51(3), 335–337.

Hien, H., & Tsunemi, W. (2018). The Roles of Three Types of Knowledge and Perceived Uncertainty in Explaining Risk Perception, Acceptability, and Self-Protective Response—A Case Study on Endocrine Disrupting Surfactants. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 15(2), 296-. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020296

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Hong, H., & Kim, H. J. (2020). Antecedents and Consequences of Information Overload in the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249305

Honora, A., Wang, K.-Y., & Chih, W.-H. (2022). How does information overload about COVID-19 vaccines influence individuals’ vaccination intentions? The roles of cyberchondria, perceived risk, and vaccine skepticism. Computers in Human Behavior, 107176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.107176

Huang, H., Su, D., & Li, W. (2016). A Study on the Relationship between Failure-Based Learning and the Innovation Behaviors: The Moderating Effects of Resilience and Perceived Organizational Support for Creativity. Science and Science and Technology Management, 37(5), 9. CNKI:SUN:KXXG.0.2016–05–016 (In Chinese)

Huynh, T. (2020). Does culture matter social distancing under the COVID-19 pandemic? Safety Science, 130, 104872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104872

Hwang, M.-Y., Hong, J.-C., Tai, K.-H., Chen, J.-T., & Gouldthorp, T. (2020). The relationship between the online social anxiety, perceived information overload and fatigue, and job engagement of civil servant LINE users. Government Information Quarterly, 37(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.101423

Islam, A., Laato, S., Talukder, S., & Sutinen, E. (2020). Misinformation sharing and social media fatigue during COVID-19: An affordance and cognitive load perspective. Technol Forecast Soc Change, 159, 120201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120201

Jacob, J., Speller, D. E., & Kohn, B. C. (1974). Brand Choice Behavior as a Function of Information Load: Replication and Extension. The Journal of Consumer Research. https://doi.org/10.1086/208579

Janssens, A. C. J., van Doorn, P. A., de Boer, J. B., van der Meché, F. G., Passchier, J., & Hintzen, R. Q. (2004). Perception of prognostic risk in patients with multiple sclerosis: the relationship with anxiety, depression, and disease-related distress. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 57(2), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00260-9

Jensen, J. D., Carcioppolo, N., King, A. J., Scherr, C. L., Jones, C. L., & Niederdeppe, J. (2014). The cancer information overload (CIO) scale: Establishing predictive and discriminant validity. Patient Education & Counseling, 94(1), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.09.016

Johnson, B. B., & Slovic, P. (1995). Presenting uncertainty in health risk assessment: Initial studies of its effects on risk perception and trust. Risk Analysis, 15(4), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb00341.x

Karreman, A., & Vingerhoets, A. J. (2012). Attachment and well-being: The mediating role of emotion regulation and resilience. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(7), 821–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.06.014

Kasperson, R. E., Renn, O., Slovic, P., Brown, H. S., Emel, J., Goble, R., Kasperson, J. X., & Ratick, S. (1988). The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis, 8(2), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1988.tb01168.x

Konaszewski, K., Kolemba, M., & Niesiobędzka, M. (2021). Resilience, sense of coherence and self-efficacy as predictors of stress coping style among university students. Current Psychology, 40(8), 4052–4062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00363-1

Kramer, A. D., Guillory, J. E., & Hancock, J. T. (2014). Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(24), 8788–8790. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320040111

Kumpfer, K. L. (2002). Factors and processes contributing to resilience. In Resilience and development (pp. 179–224). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47167-1_9

Kuo, B. C. (2013). Collectivism and coping: Current theories, evidence, and measurements of collective coping. International Journal of Psychology, 48(3), 374–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.640681

Laato, S., Islam, A. K. M. N., Farooq, A., & Dhir, A. (2020). Unusual purchasing behavior during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: The stimulus-organism-response approach. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102224

Lang, A. (2000). The Limited Capacity Model of Mediated Message Processing. Journal of Communication, 50, 46–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02833.x

Lang, M., Buch, K., Li, M. D., Mehan, W. A., Jr., Lang, A. L., Leslie-Mazwi, T. M., & Rincon, S. P. (2020). Leukoencephalopathy Associated with Severe COVID-19 Infection: Sequela of Hypoxemia? AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 41(9), 1641–1645. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6671

Lazarus, R. S., Averill, J. R., & Opton Jr, E. M. (1970). Towards a cognitive theory of emotion. In Feelings and emotions (pp. 207–232). Elsevier.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

Lazarus, R. S., & Launier, R. (1978). Stress-Related Transactions between Person and Environment. Springer.

Leal, P. C., Goes, T. C., da Silva, L. C. F., & Teixeira-Silva, F. (2017). Trait vs. state anxiety in different threatening situations. Trends Psychiatry Psychother, 39(3), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2016-0044

Lee, A. R., Son, S.-M., & Kim, K. K. (2016). Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: A stress perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.011

Lee, Y. C., Wu, W. L., & Lee, C. K. (2021). How COVID-19 Triggers Our Herding Behavior? Risk Perception, State Anxiety, and Trust. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 587439. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.587439

Leppin, A., & Aro, A. R. (2009). Risk perceptions related to SARS and avian influenza: Theoretical foundations of current empirical research. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 16(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-008-9002-8

Li, H., & Lopez, V. (2010). Do trait anxiety and age predict state anxiety of school-age children? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14(9), 1083–1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01223.x

Li, Q., Luo, R., Zhang, X., Meng, G., Dai, B., & Liu, X. (2021). Intolerance of covid-19-related uncertainty and negative emotions among chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model of risk perception, social exclusion and perceived efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18062864

Li, W., & Yuan, Y. (2018). Purchase experience and involvement for risk perception in online group buying. Nankai Business Review International. https://doi.org/10.1108/NBRI-11-2017-0064

Li, Y., & Wu, D. (2016). Procedural Justice and Employee's Job Engagement: The Impacts of State Anxiety and Supervisor Communication. Science and Science and Technology Management, 37(5), 12. NKI:SUN:KXXG.0.2016–05–014 (In Chinese)

Li, Z.-S., & Hasson, F. (2020). Resilience, stress, and psychological well-being in nursing students: A systematic review. Nurse Education Today, 90, 104440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104440

Liu, C.-F., & Kuo, K.-M. (2016). Does information overload prevent chronic patients from reading self-management educational materials? International Journal of Medical Informatics, 89, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.01.012

Liu, H., & Wang, W. (2017). The relationship between negative life events and state anxiety in college students: The mediating effect of rumination thinking and the moderating effect of self-affirmation. Chinese Journal of Mental Health, 31(9), 6. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2017.09.012 In Chinese.

Liu, M., Zhang, H., & Huang, H. (2020). Media exposure to COVID-19 information, risk perception, social and geographical proximity, and self-rated anxiety in China. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09761-8.

Liu, H., Liu, W., Yoganathan, V., & Osburg, V.-S. (2021). COVID-19 information overload and generation Z's social media discontinuance intention during the pandemic lockdown. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120600

Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K., & Welch, N. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.127.2.267

Long, W., Canhua, K., Zongyi, Y., Fang, S. (2019). Psychological Endurance, Anxiety, and Coping Style among Journalists Engaged in Emergency Events: Evidence from China. Iranian Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v48i1.787

Lu, F. J. H., Lee, W. P., Chang, Y.-K., Chou, C.-C., Hsu, Y.-W., Lin, J.-H., & Gill, D. L. (2016). Interaction of athletes’ resilience and coaches’ social support on the stress-burnout relationship: A conjunctive moderation perspective. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22, 202–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.08.005

MacKinnon, D. P. (2012). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Routledge.

Malhotra, N. K. (1982). Information Load and Consumer Decision Making. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(4), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1086/208882

Mallett, R., Coyle, C., Kuang, Y., & Gillanders, D. T. (2021). Behind the masks: A cross-sectional study on intolerance of uncertainty, perceived vulnerability to disease and psychological flexibility in relation to state anxiety and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic - ScienceDirect. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.09.003

Matthes, J., Karsay, K., Schmuck, D., & Stevic, A. (2020). “Too much to handle”: Impact of mobile social networking sites on information overload, depressive symptoms, and well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106217

Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. The MIT Press.

Mestre, J. M., Núñez-Lozano, J. M., Gómez-Molinero, R., Zayas, A., & Guil, R. (2017). Emotion regulation ability and resilience in a sample of adolescents from a suburban area. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1980.

Meyer, J. A. (1998). Information overload in marketing management. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 16(3), 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634509810217318

Misra, S., & Stokols, D. (2011). Psychological and Health Outcomes of Perceived Information Overload. Environment and Behavior, 44(6), 737–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916511404408

Mohammed, M., Sha’aban, A., Jatau, A. I., Yunusa, I., Isa, A. M., Wada, A. S., Obamiro, K., Zainal, H., & Ibrahim, B. (2021). Assessment of COVID-19 Information Overload Among the General Public. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00942-0

Monroe, S. M., & Simons, A. D. (1991). Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin, 110(3), 406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406

Moos, R. H. (2002). 2001 Invited address: The mystery of human context and coping: An unraveling of clues. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(1), 67–88. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014372101550

Ng, Y. J., Yang, Z. J., & Vishwanath, A. (2017). To fear or not to fear? Applying the social amplification of risk framework on two environmental health risks in Singapore. Journal of Risk Research, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2017.1313762

O’Reilly, C. A., III. (1980). Individuals and information overload in organizations: Is more necessarily better? Academy of Management Journal, 23(4), 684–696.

Odone, A., Delmonte, D., Scognamiglio, T., & Signorelli, C. (2020). COVID-19 deaths in Lombardy, Italy: data in context. The Lancet Public Health, 5(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30099-2

Oyserman, D. (2017). Culture Three Ways: Culture and Subcultures Within Countries. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 435–463. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033617

Patel, M., Kute, V., & Agarwal, S. (2020). "Infodemic" of COVID 19: More pandemic than the virus. Indian Journal of Nephrology, 30(3). https://doi.org/10.4103/ijn.IJN_216_20

Patwa, P., Sharma, S., Pykl, S., Guptha, V., Kumari, G., Akhtar, M. S., ... & Chakraborty, T. (2021). Fighting an infodemic: Covid-19 fake news dataset. In international workshop on combating on line hostile posts in regional languages during emergency situation (pp. 21–29). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73696-5_3

Peng, F., Tu, L., Yang, Y., Hu, P., Wang, R., Hu, Q., Cao, F., Jiang, T., Sun, J., & Xu, G. (2020). Management and treatment of COVID-19: The Chinese experience. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 36(6), 915–930. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072304

Pero, C. L., Valacich, J. S., & Vessey, I. (2010). The Influence of Task Interruption on Individual Decision Making: An Information Overload Perspective. Decision Sciences, 30(2), 337–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1999.tb01613.x

Phillips-Wren, G., & Adya, M. (2020). Decision making under stress: The role of information overload, time pressure, complexity, and uncertainty. Journal of Decision Systems, 29(sup1), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/12460125.2020.1768680

Pietrzak, R. H., Johnson, D. C., Goldstein, M. B., Malley, J. C., & Southwick, S. M. (2009). Psychological resilience and postdeployment social support protect against traumatic stress and depressive symptoms in soldiers returning from Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Depression and Anxiety, 26(8), 745–751. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20558

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among U.S. young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.013

Quan, L., Zhen, R., Yao, B., & Zhou, X. (2020). Traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among flood victims: Testing a multiple mediating model. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(3), 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317707568

Rathore, F. A., & Farooq, F. (2020). Information Overload and Infodemic in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 70(5), S-162-165. https://doi.org/10.5455/JPMA.38

Ren, X. (2020). Anxiety research on the state anxiety of candidates for the physical education entrance examination in Lanzhou City [Master thesis, Northwest Normal University].

Ren, J., Li, X., Chen, S., Chen, S., & Nie, Y. (2020). The Influence of Factors Such as Parenting Stress and Social Support on the State Anxiety in Parents of Special Needs Children During the COVID-19 Epidemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 565393. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565393

Renjith, R. (2017). The effect of information overload in digital media news content. Communication and Media Studies, 6(1), 73–85.

Shenk, D. (1997). Data Smog: Surviving the Info Glut. Technology Review, 100(4), 18–26.

Slovic, P. (1987). Perception of risk. Science, 236(4799), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3563507

Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2004). Risk as analysis and risk as feelings: Some thoughts about affect, reason, risk, and rationality. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 24(2), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x.

Sobkow, A., Traczyk, J., & Zaleskiewicz, T. (2016). The Affective Bases of Risk Perception: Negative Feelings and Stress Mediate the Relationship between Mental Imagery and Risk Perception. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 932. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00932

Sojo, V., & Guarino, L. (2011). Mediated moderation or moderated mediation: Relationship between length of unemployment, resilience, coping and health. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 14(1), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_SJOP.2011.v14.n1.24

Soroya, S. H., Farooq, A., Mahmood, K., Isoaho, J., & Zara, S. E. (2021). From information seeking to information avoidance: Understanding the health information behavior during a global health crisis. Information Processing and Management, 58(2), 102440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102440

Speth, M. M., Singer-Cornelius, T., Oberle, M., Gengler, I., Brockmeier, S. J., & Sedaghat, A. R. (2020). Olfactory Dysfunction and Sinonasal Symptomatology in COVID-19: Prevalence, Severity, Timing, and Associated Characteristics. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 163(1), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820929185

Spielberger, C. D. (1966). Theory and research on anxiety. Anxiety and behavior (pp. 3–20). Academic Press.

Spielberger, C. D. (1972). Conceptual and methodological issues in anxiety research. Current trends in theory and research (pp. 481–493). Academic Press.

Speilberger, C. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety STAI (Form Y. Consulting Psychologists Press.

Spielberger, C. D. (2010). State‐Trait anxiety inventory. The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology, 1-1. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0943

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning. Cognitive Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/0364-0213(88)90023-7

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Ullman, J. B. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (vol. 5, pp. 481–498). Pearson

Tan, Y., Wang, L., & Huang, J. (2021). Differences and influencing factors for mortality rate of COVID-19: Based on age structure and testing rate. Population Research, 45(2), 30–46 (In Chinese).

Tang, J., & Gibson, S. J. (2005). A psychophysical evaluation of the relationship between trait anxiety, pain perception, and induced state anxiety. Journal of Pain Official Journal of the American Pain Society, 6(9), 612–619.

Tang, L., Zhu, Y., Liu, M., Zhang, X., & Chen, R. (2021). Thoughts on the participation of social organizations in the regular prevention and control of COVID-19. Chinese Rural Health Service Administration, 41(3), 4. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-5916.2021.03.004 In Chinese.

Traczyk, J., Sobkow, A., & Zaleskiewicz, T. (2015). Affect-laden imagery and risk taking: The mediating role of stress and risk perception. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0122226. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122226

Tugade, M. M., Fredrickson, B. L., & Feldman Barrett, L. (2004). Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1161–1190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x

Tzafilkou, K., Perifanou, M., & Economides, A. A. (2021). Negative emotions, cognitive load, acceptance, and self-perceived learning outcome in emergency remote education during COVID-19. Education and Information Technologies(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10604-1

Uddin, S., Imam, T., Moni, M. A., & Thow, A. M. (2020). Onslaught of COVID-19: How Did Governments React and at What Point of the Crisis? Population Health Management, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2020.0138

Valika, T. S., Maurrasse, S. E., & Reichert, L. (2020). A Second Pandemic? Perspective on Information Overload in the COVID-19 Era. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 163(5), 931–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820935850

Wang, S. (2020). Ten characteristics of “Infodemic”. Library Journal 39(3), 5. https://doi.org/10.13663/j.cnki.lj.2020.03.002 (In Chinese)

Wang, Y., & Wang, P. (2019). Perceived stress and psychological distress among chinese physicians: The mediating role of coping style. Medicine, 98(23). https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015950