Abstract

The literature suggests that alexithymia and emptiness could be risk factors for various addictive behaviors. The present study developed and tested a model that proposes a pathway leading from emptiness and difficulties in identifying emotions to Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) symptoms via an intense gamer-avatar relationship and bodily dissociative experiences. A sample of 285 (64.2% M; mean age = 30.38 ± 7.53) online gamers using avatar-based videogames was recruited from gaming communities, and they were asked to complete a survey that included the Toronto Alexithymia Scale, the Subjective Emptiness scale, the Scale of Body Connection, the Self-Presence Questionnaire, and the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form. The structural model evaluated produced a good fit to the data [χ2 = 175.14, df = 55, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.08 (90% C.I. =0.07–0.09), CFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.08] explaining 28% of the total variance. Alexithymia was indirectly associated with IGD through the serial mediation of the gamer-avatar relationship and body dissociation. Emptiness was associated with IGD symptoms at the bivariate level, but did not predict IGD directly or indirectly. The current study identifies a potential pathway toward IGD by integrating different lines of research, showing the importance of considering aspects such as the difficulty in recognising and expressing one’s emotions, the gamer- avatar relationship, and the mind-body connection in the context of IGD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the 21st century, the rapid improvement of technologies and their increased accessibility have led to an increase in technology-related risks. In particular, one of the most problematic issues related to technology is Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD). The latest editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, 2013) included IGD in section III ‘Conditions for Further Study’ and the International Classification of Disease and Related Health-Problems (ICD-11, 2019) conceptualises IGD as a behavioural addiction, basing the criteria on those of substance and gambling disorders. Whilst the diagnostic criteria for gaming disorder is still the subject of debate (see Király et al., 2015; Castro-Calvo et al., 2021), there is no doubt that excessive video gaming is associated with negative outcomes on certain players (Altintas et al., 2019). Consequently, increasing efforts have been put into identifying common and specific factors that promote IGD development.

One line of research is undoubtedly focused on the role of the user-avatar bond, as the player representation that is projected into virtual environments (i.e., the avatar) is one of the important elements of online gaming. Avatars have been proposed to be “far more than mere online objects manipulated by a user.” They are “the embodied conception of the participant’s self through which she communicates with others in the community” (Wolfendale, 2007, p.114), and they might be experienced as being expressive of one’s own personal identity even in the cases in which players choose avatars with physical, emotional and personality traits different from their actual trait (Wolfendale, 2007). This might be explained through a psychodynamic lens suggesting that avatars allow the gamers to express suppressed versions of their psyche or unconscious states of mind (Schimmenti & Caretti, 2010; Stavropoulos et al., 2020). However, the extent to which the player feels a bodily and emotional connection with the avatar (i.e., the gamer- avatar relationship, Ratan & Dawson 2016) has been proposed as a key risk mechanism in IGD development. Empirical evidence supporting the link between the gamer-avatar relationship and IGD symptoms has been growing year on year (Green et al., 2020, 2021a), even via sound research designs and different methodologies. For instance, Burleigh et al. (2018) examined the link between the gamer-avatar relationship and IGD symptoms combining a cross-sectional and longitudinal design. They found that the former acts as an individual risk factor in the latter’s development over time. Leménager et al. (2016) used functional magnetic resonance and reported that problematic gamers exhibit greater brain activity during avatar-reflection. A recent systematic review on this topic (Leménager et al., 2020) concluded that a stable moderate link between the gamer-avatar relationship and IGD symptoms was reported in problematic gamers. However, a very recent qualitative investigation (Green et al., 2021b) has shown that in most cases players tend to anticipate feelings of frustration or annoyance when asked to think about losing their avatar, but also express a view of avatars as being no more than a means of achieving in-game goals. This confirms that emotional and bodily connection with the avatar should not be considered as inherently problematic, as it can be a part of the ‘fun’ of gaming. These results, taken as a whole, suggest that the link between the gamer-avatar relationship and IGD deserves the scientific attention it is currently receiving, and they highlight the need to identify the psychosocial mechanisms leading to a problematic gamer- avatar relationship – that is, a level of attachment/bond that might explain the pathway towards IGD.

Gamer-Avatar Relationship: Precursors and Potential Indirect Effects on IGD

The Compensatory Internet Use Theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014) suggests that problematic use of technology might be motivated by unfulfilled fundamental needs. Following the Self-discrepancy Theory (SDT; Higgins, 1987), it has been proposed that, when it comes to IGD, these fundamental needs concern identity and have an impact on the player’s experience with the avatar (e.g., Li et al., 2011). That is, it has been suggested that avatar identification represents a risk factor especially for individuals with identity needs (i.e., needs to mitigate the discrepancy between discordant aspects of oneself). In detail, according to the SDT, large discrepancies between the real self (i.e., our representation of the attributes we believe to possess or that we believe others think we possess), the ought self (i.e., the representation of how we believe we must be and of the obligations and responsibilities we believe we have or others think we must have) and the ideal self (i.e., hopes, desires, or aspirations we would like for ourselves or thinks others would like for us), lead to experiencing a lack of fulfilment, which would increase the attachment/connection to the avatar. In other words, players might unwittingly try to gain identity fulfilment through their avatars. This avatar connection, in turn, would increase the IGD risk (see Leménager et al., 2020 for a systematic review of related empirical evidence).

These results are in keeping with the general view of addictive behaviors as maladaptive responses to an identity void (Islas-Limòn et al., 2019) or dysfunctional strategies to gain a sense of self when – otherwise - there would be a feeling of emptiness (Pickard, 2020) or difficulties in identifying and expressing one’s own feelings. McDougall (1982) argues that fears such as self-fragmentation and loss identity-feelings are usually faced with alexithymic phenomena. That is, the inability to name, recognise and express one’s emotions and affective states could represent a defence against these fears, a means of minimise one’s own emotional involvement and protect oneself from pain. Empirical evidence (e.g., Besharat & Shahidi 2011; Evren et al., 2012; Fang et al., 2020; Helmes et al., 2008 Kooiman et al., 1998; Parker et al., 1998) suggests strong associations between alexithymia and immature or maladaptive ego defense styles in clinical and nonclinical populations. Following this perspective, alexithymic people may be more comfortable keeping in touch their feelings through an avatar, as this allows them to experience emotions in a mitigated and protected way through the virtual world. In fact, alexithymia has been consistently found to be positively associated with addictive behaviors, including IGD (e.g., Bonnaire & Baptista, 2019; Li et al., 2021; Maganuco et al., 2019). Interestingly, the potentially mediating role of the gamer-avatar relationship in the relationship between alexithymia and IGD has not been given much scientific attention. This might be due to the fact that the positive association between alexithymia and IGD is generally explained by calling into question explanations derived from the field of substance abuse, that is arguing that people who have difficulties in identifying, regulating and communicating their feelings may use video games to escape from negative affects (e.g., Di Blasi et al., 2019; Maganuco et al., 2019). However, there might be also room to hypothesize that the gamer-avatar relationship plays a mediating role in the link between empty feelings and IGD, as the avatar might provide the opportunity to connect with (and experience) suppressed or unexpressed emotions in a protected environment (i.e., through the avatar itself). That is, it might be the case that playing avatar-based games is not only a vehicle for regulating emotions through escape mechanisms, but also a means to connect with or experience them through a vicarious self. Moreover, the identification with the avatar could also help people with low purposes or meaning in life (i.e. individuals perceiving low significance in their lives) to obtain a scope and a sense of meaning through the game aims. In fact, prior studies found meaning in life to be negatively associated with IGD (e.g., Zhang et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2013). Following this line of reasoning, we wanted to explore the indirect role of emptiness and alexithymia (i.e., “empty feelings”) on IGD symptoms through the gamer- avatar relationship.

An additional point warranting scientific attention is that technology use is often characterized by a spiral effect, that is, it tends to reinforce the needs that led to its use in the first place (Slater, 2007). Individuals who experience “empty feelings” may find it easier to express themselves through an avatar by projecting their emotional aspects onto it, thus experiencing high levels of avatar identification. However, spending time in a virtual body and experiencing high levels of identification with it might increment a sense of detachment from oneself and/or one’s own physical body, which represents a vulnerability that poses a risk for IGD. In fact, recent studies have shown that bodily disconnection – avoidance and separation from bodily experience or the bodily self which is thought to be a protective strategy against painful memories, thoughts, or feelings – predict IGD symptoms after controlling for well-established risk factors (Casale et al., 2021). Interestingly, very few studies have explored the links between “empty feelings,” the gamer-avatar relationship and bodily dissociative experiences, and to our knowledge no studies have examined the potential mediating role of bodily dissociative experiences in the association between the gamer-avatar relationship and IGD symptoms.

The current study provides an integration of different theoretical perspectives and lines of research into IGD. On the one hand, convergent results on the role of the difficulties in identifying feelings predicting IGD symptoms have been provided (Li et al., 2021; Maganuco et al., 2019). On the other hand, there is either abundant empirical evidence of the link of IGD with dissociation (see, for a review, Guglielmucci et al., 2019) and the gamer-avatar relationship (see, for a review, Green et al., 2020). These previous findings encourage us to propose and test an overarching model that brings together these variables, as such an effort might be of help in clarifying the pathways towards IGD. The present study developed and tested a model (Fig. 1) that explains how people who feel a sense of emptiness and difficulties in identifying their emotions develop IGD symptoms through an intense gamer-avatar relationship and dissociative experiences. In detail, the present study tested a serial mediation model, whereby it was hypothesised that the gamer- avatar relationship and bodily dissociative experiences were serial mediators of the relationship between alexithymia and emptiness, on the one hand, and IGD symptoms, on the other. Due to the use of cross-sectional data (rather than longitudinal data), the hypothesized model will be compared with a hypothesized alternative equivalent model, which will be discussed in the "Statistical Analysis" section.

Method

A sample of 285 Italian online gamers (64.2% M), aged between 15 and 65 years (mean age 30.38 ± 7.53 years) was anonymously recruited via online advertisements, which were shared on ten Facebook and Telegram video games groups. The inclusion criteria were: age over 15 years and playing an online game involving the use of an avatar. Participation was voluntary (no incentive was given). Informed consent was obtained for all participants. In accordance with the Italian law, parental consent was not required for participants over 14 years old. The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of the University of *** approved the study.

Measures

Data collection consisted of online questionnaires. Socio-demographic information such as age, sex, relationship status and educational level was collected.

Gaming Habits

Data on gaming habits were collected by asking participants the number of hours spent video-gaming in a typical week (i.e., number of sessions per week and minutes per session) and how long they have been using video games.

Alexithymia

The Italian version (Bressi et al., 1996) of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20; Taylor et al., 1992) is a well-validated self-report measure of alexithymia consisting of 20 items. It comprises three factors: difficulty describing feelings (5 items, a sample item is “I am able to describe my feelings easily”), difficulty identifying feelings (7 items, a sample item is “‘I am often confused about what emotion I am feeling”), and externally-oriented thinking (8 items, a sample item is “looking for hidden meanings in movies or plays distracts from their enjoyment”). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (strongly agree”). Total scores range from 20 to100, with higher scores indicating higher levels of alexithymia. In the current study, we calculated and used the TAS-20 total score. Cronbach’s alpha in this study for the total score was α = 0.82.

Emptiness

The Italian version (D’Agostino et al., 2021) of the Subjective Emptiness Scale (SES, Price et al., 2019) was used. The SES is a 7-item self-report measure (a sample item is “I feel hollow”) with supported unidimensionality, internal consistency, and construct validity. It is a tool specifically designed to assess subjective emptiness beyond the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) with which it is usually associated. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (“Not at all true”) to 4 (“very true”). Total scores range from 7 to 28, with higher scores indicating higher levels of alexithymia. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was α = 0.91.

Gamer-Avatar Relationship

The gamer-avatar relationship was assessed through the 13-item version of the Self-Presence questionnaire (SPQ, Ratan & Dawson, 2016) which measures the avatar-body connection, the avatar-emotion connection, and the avatar-identity connection (sample items are “to what extent is your avatar’s appearance related to some aspect of your personal identity” and “when sad events happen to your avatar, to what extent do you feel sad?”). The total score is given on a scale from 13 to 65. Participants responded to the items using a 5-point Likert from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“absolutely”), with higher scores indicating higher connection between an individual and their avatar. The reliability and construct validity of the total scale has been supported by previous research (e.g., Ratan & Hasler, 2010; Stavropoulos et al., 2022). The scale was translated from English into Italian in accordance with the recommendations of the International Test Commission (2005). Exploratory Factor Analysis revealed that the Italian SPQ had a three-factor solution, similar to the original version, explaining the 66% of the variance. A total score can also be computed (see for example Burleigh et al., 2018; Liew et al., 2018). Cronbach’s alpha in this study was α = 0.87.

Body Dissociation

Body dissociation was assessed through the 8-item subscale of the Body Connection Scale (SBC, Price & Thompson, 2007). This subscale measures disconnection or separation from the body, including emotional disconnection (a sample item is “I feel like I am looking at my body from outside of my body”). Participants responded to the items using a 5-point scale from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“always”). In the current study, the total score was calculated by summing up the responses to each question. Higher scores indicate higher body dissociation. The Italian version of the SBC (Morganti et al., 2020) showed adequate psychometric characteristics. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was α = 0.74.

IGD Symptoms

The Internet Gaming Disorder scale- Short Form (IGD9-SF, Pontes & Griffiths, 2015; Italian adaptation by Monacis et al., 2016) was used. The IGD9-SF is based on DSM-5 criteria for IGD (e.g., preoccupation with Internet games; withdrawal behaviours when Internet gaming is taken away). Participants responded to the items using a 5-point Likert from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“very often”). Scores range from 9 to 45, with the higher scores indicating the greater presence of IGD symptoms. Findings confirmed the single-factor structure of the Italian version, and the convergent and criterion validities. Monacis et al. (2016) identified a cut-off value of 21 to distinguish disordered and non-disordered gamers. Cronbach’s alpha in this study was α = 0.86.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s Product Moment correlations between the study variables were computed. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was performed to test the hypothesized effects. Parcelling was computed using an empirically equivalent method (Landis et al., 2000). Items were assigned in such a way that parcels will have equal means, variances, and reliabilities. SEM was conducted using LISREL 8.8 with the Robust Maximum Likelihood (RML) estimation method (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2006). The following profile of goodness of fit indices was considered: the χ2 (and its degrees of freedom and p-value), the Standardized Root Mean square Residual (SRMR - Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993) ‘‘close to’’ 0.09 or lower, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI - Bentler, 1995) ‘‘close to’’ 0.95 or higher (Hu & Bentler, 1999), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA - Steiger, 1990) less than 0.08 (Brown & Cudeck, 1993). Indirect effects were tested with a distribution of the product coefficients (P) test developed by MacKinnon et al. (1998, 2002). Outliers, multivariate, and univariate non-normality were handled using the Robust Maximum Likelihood (RML) estimation method (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2006) in SEM analysis.

When using structural equation modeling, Kline (2011) suggested investigations of predicted models include comparison to hypothesized alternative equivalent models. Though fit statistics can be calculated for a hypothesized model, it is possible to have different theoretically plausible configurations of the paths in a model and yield similar mathematical fit statistics. Thus, by comparing the two models, an argument can be made that one model may be more plausible, rather than simply preferring one model over the other. In the current study, in the hypothesized alternative equivalent model the dependent and the independent variables were reversed, and two serial mediational paths were examined. In the first path it was hypothesized that alexithymia and gamer-avatar relationship were serial mediators of the relationship between IGD symptoms and bodily dissociative experiences. In the second path it was hypothesized that feeling of emptiness and gamer-avatar relationship were serial mediators of the relationship between IGD symptoms and bodily dissociative experiences.

Results

Participants report that they spend 15.74 ± 12.83 h playing during a typical week. 86.2% of the participants (n = 246) declare that they had been playing for at least two years (24 months) and 68% of the participants (n = 194) reported they had started playing more than 10 years ago (120 months). The majority of participants reported playing multiplayers online role-playing games (MORPG; 40%) or multiplayers online first-person shooter (MOFPS; 33,4%). Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1.

Statistically significant correlations in the expected direction were found between the predictor variables, the mediators and IGD (Table 2).

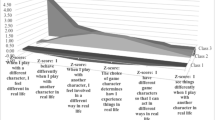

The structural model produced adequate fit to the data (χ2 = 175.14; df = 55; p < .001; RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.07 [0.06–0.08]; CFI = 0.96; SRMR = 0.08). All coefficients estimated for the measurement model and the estimates of error variances were significant. The variables in the model accounted for 28% of the variance in participants’ IGD levels. The standardized beta coefficients are shown in Fig. 2. Unstandardized values with standard errors are presented in Table 3. The results supported the hypothesized indirect relationship between difficulties in identifying emotions and body dissociation mediated by the gamer-avatar relationship (P = 9.67 p < .05). Difficulty in identifying emotions was found to be indirectly associated to IGD through the mediating serial role of the gamer-avatar relationship and body dissociation (P = 58.02 p < .05). A significant indirect effect of the gamer- avatar relationship on IGD levels mediated by body dissociation was also found (P = 18.66 p < .05). The analysis revealed a significant direct effect of difficulties in identifying emotions in the gamer-avatar relationship, whereas no significant effect was found for feelings of emptiness.

Effect of empty feelings on IGD through the serial mediating role of the gamer-avatar relationship and physical body dissociation. Notes. DDF = difficulty describing feelings; DIF = difficulty identifying feelings; EOT = externally-oriented thinking; SES1, SES2 = Subjective Emptiness Scale parcels; ABC = avatar-body connection; AEC = avatar-emotion connection; AIC = avatar-identity connection; BD1, BD2 = Body dissociation subscale parcels; IGD1, IGD2, IGD3 = Internet Gaming Disorder scale parcels;**p < .001

The hypothesized alternative equivalent model yielded the following fit statistics: χ2 = 312.80; df = 56; p < .001; RMSEA [90% CI] = 0.13 [0.11–0.14]; CFI = 0.91; SRMR = 0.10. The alternative equivalent model has a poorer fit than the hypothesized model.

Discussion

The association between alexithymia and IGD symptoms has already been documented previously (Bonnaire & Baptista, 2019; Gaetan et al., 2016; Li et al., 2021), and a decade of studies have also shown a quite robust association between the gamer-avatar relationship and IGD (Green et al., 2020). The present study aimed to provide an integration of these two research lines by proposing and testing a model that explains how people who report “empty feelings” (i.e., emptiness and difficulties in identifying and expressing their feelings) develop IGD symptoms. Following a psychodynamic perspective and previous evidence about the role that the bond with the avatar might play in IGD development, the gamer-avatar relationship and bodily dissociation were hypothesized to serially mediate the association between empty feelings and IGD symptoms.

When it comes to alexithymia, the preliminary correlational analysis indicated that it has a positive association with player-avatar connection levels; a positive association with bodily dissociative experiences; and a positive association with IGD symptoms. The relationship between alexithymia and IGD symptoms was then found to be mediated by the serial mediation pathway via the gamer-avatar relationship and bodily dissociative experiences. The present study contributes to the literature by highlighting that the well-established alexithymia-IGD link (Bonnaire & Baptista, 2019; Maganuco et al., 2019) is mediated by the gamer- avatar relationship, supporting our previously untested hypothesis that the greater the difficulties in identifying and expressing one’s own feelings, the greater the player-avatar connection. In other words, high alexithymia might at least in part be responsible for a high player-avatar connection. These results might be interpreted in a psychodynamic framework suggesting that virtual identities are used by alexithymic players as a vehicle to experience and express aspects of their own personality that might be problematic to tap into in actual “physical” life, which in turn might contribute to a stronger gamer-avatar relationship. That is, within a psychodynamic perspective avatar-related experiences might represent an opportunity for the player to connect with some repressed or unexpressed emotions and experience them in a protected environment (i.e., the videogame), in which relationships with others are safer because they are ‘physically distant’ and mediated not by one’s own body but by the avatar itself. In this perspective, interacting through an avatar in a virtual world might not be an escape mechanism for alexithymic individuals, but rather a way in which the player can connect to their emotions and experience them through a vicarious self without endangering their sense of personal safety. However, although our study cannot clarify the direction of the associations, consistently with prior studies we also find support for the view (Green et al., 2020, 2021a) that players who tend to have high levels of identification with the avatar could share a common susceptibility for IGD. Our results offer additional empirical evidence of this link, but also add to previous findings in that they highlight that alexithymia might be one responsible for higher levels of player-avatar connection which, in turn, is predictive of IGD symptoms. The current study also builds on previous findings in that it found evidence in favour of an indirect effect of the gamer-avatar relationship on IGD through bodily dissociative experiences. The current study replicates past findings that bodily disconnection has an effect on IGD, supporting the notion that the strong connection with the game’s virtual character and the large amount of time spent in the avatar could distance players from their bodily and physical self, leading to a greater avoidance of internal experience (Casale et al., 2021). Apart from supporting this previous evidence, we also offer additional explanations highlighting that the temporary identification with the character might induce separation from one’s own physical self.

Interestingly, we found a significant association between emptiness and IGD only at the bivariate level, as alexithymia emerged as the only significant IGD predictor through the serial mediation of avatar identification and body disconnection in the structural equation model. One possible explanation is that alexithymia obscures the emptiness-IGD link in that a certain degree of ability to identify emotions is needed in order to recognize and discern emptiness. That is, it might be the case that strong difficulties in identifying emotions imply difficulties in identifying emptiness. However, we also believe that the emptiness-IGD link might warrant further scientific attention, given that the bivariate correlation between emptiness and IGD was moderate, and emptiness and alexithymia were associated significantly with each other but not to the extent of being redundant (r = .53). For individuals who do not experience difficulties in recognizing their emotions, emptiness might be a risk factor for IGD via the same pathways (i.e., player-avatar identification and bodily dissociation) already highlighted for alexithymic individuals in the current research.

Our findings also imply the need to integrate other factors that have been found to have an impact on IGD, as the variance explained by our model is not particularly high. Reward-related decision-making deficits (Cheng et al., 2021), metacognitions about online gaming (Casale et al., 2021; Spada & Caselli, 2017), boredom proneness (Aydın et al., 2022) have been found to be related to IGD, thus suggesting that they should be further considered by future research. Moreover, conflicting results have been reported regarding the relevance of the avatar in determining IGD. Some studies (e.g., Entwistle et al., 2020) did not find an association between game genre and IGD severity whilst some others support that some online games have different addictive potential depending on the chance for players to take on the roles and identities of self-created fictitious characters (for a systematic review about maladaptive player-game relationship in problematic gaming see King et al., 2019). In any case, there is evidence that the avatar is not a sufficient factor for IGD but rather is, in many cases, just a part of the ‘fun’ of gaming (Green et al., 2021b). On the one hand, this tends to support that it is not the player-avatar bond itself to be inherently problematic but rather the motivations surrounding this bond. On the other hand, this suggests that factors unrelated to the avatar-player bond (e.g., impulsivity) might be relevant in explaining IGD.

The current study adopted a cross-sectional design, preventing us from drawing causal inferences. Nevertheless, the comparison of the two models suggests that there is stronger evidence for the role of alexithymia predicting IGD symptoms (via game-avatar identification and body dissociation) rather than the opposite. Our results encourage us to set up future lines of research that experimentally investigate the link between the study variables. In detail, experimental designs might help to clarify whether a strong bond with the avatar has the potential to disconnect a player from one’s own body or whether a bidirectional or reciprocal effect exists, so that playing online strengthens the body disconnection. Furthermore, we did not recruit an IGD-diagnosed sample and results in a ‘clinical’ population might be different. In addition, an online survey was used without having information on the psychometric equivalence of the measures used.

Despite these limitations, the current study offers new insights into the literature by revealing the possibilities of pathways in explaining the relationship between alexithymia, player-avatar identification, and IGD symptoms. Our results may be informative for clinicians who work with individuals that manifest problematic video game use. In fact, they show the potential importance, in the context of gaming-related problems, of working on emotions and focusing on the mind-body connection, enhancing the perception of what one experiences and feels. For example, it could be useful to plan interventions designed to improve the ability to reflect on one’s mental states. This focus could help clinicians to understand the factors underlying problematic gaming patterns, thus helping them to provide tailored psychological interventions for people with problematic gaming.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on request.

Change history

25 August 2022

The original version of this article was updated to add the Funding information.

References

Altintas, E., Karaca, Y., Hullaert, T., & Tassi, P. (2019). Sleep quality and video game playing: Effect of intensity of video game playing and mental health. Psychiatry Research, 273, 487–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.030

Aydın, O., Ünal-Aydın, P., Caselli, G., Kolubinski, D. C., Marino, C., & Spada, M. M. (2022). Psychometric validation of the desire thinking questionnaire in a Turkish adolescent sample: Associations with internet gaming disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 125107129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107129

Besharat, M. A., & Shahidi, S. (2011). What is the relationship between alexithymia and ego defense styles? A correlational study with Iranian students. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 4, 145–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2011.05.011

Burleigh, T. L., Stavropoulos, V., Liew, L. W., Adams, B. L., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Depression, internet gaming disorder, and the moderating effect of the gamer-avatar relationship: An exploratory longitudinal study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(1), 102–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9806-3

Bonnaire, C., & Baptista, D. (2019). Internet gaming disorder in male and female young adults: The role of alexithymia, depression, anxiety and gaming type. Psychiatry Research, 272, 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.158

Bressi, C., Taylor, G., Parker, J., Bressi, S., Brambilla, V., Aguglia, E., et al. (1996). Cross validation of the factor structure of the 20-item Toronto alexithymia scale: An Italian multicenter study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 41, 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00228-0

Brown, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Casale, S., Musicò, A., & Schimmenti, A. (2021). Beyond internalizing and externalizing symptoms: The association between body disconnection and the symptoms of internet gaming disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 123, 107043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107043

Casale, S., Musicò, A., & Spada, M. M. (2021). A systematic review of metacognitions in Internet Gaming Disorder and problematic Internet, smartphone and social networking sites use. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28, 1494–1508. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2588

Castro-Calvo, J., King, D. L., Stein, D. J., Brand, M., Carmi, L., Chamberlain, S. R., & Billieux, P. (2021). Expert appraisal of criteria for assessing gaming disorder: An international Delphi study. Addiction, 116(9), 2463–2475. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15411

Cheng, Y. S., Ko, H. C., Sun, C. K., & Yeh, P. Y. (2021). The relationship between delay discounting and Internet addiction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 114, 106751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106751

D’Agostino, A., Pepi, R., Monti, R., Starcevic, R., & Price, A. (2021). Measuring emptiness: Validation of the Italian version of the Subjective Emptiness Scale in clinical and non-clinical populations. Journal of Affective Disorder Reports, 6, 100226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100226

Di Blasi, M., Giardina, A., Giordano, C., Coco, G. L., Tosto, C., Billieux, J., & Schimmenti, A. (2019). Problematic video game use as an emotional coping strategy: Evidence from a sample of MMORPG gamers. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(1), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.02

Entwistle, G. J. M., Blaszczynski, A., & Gainsbury, S. M. (2020). Are video games intrinsically addictive? An international online survey. Computers in Human Behavior, 112, 106464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106464

Evren, C., Cagil, D., Ulku, M., Ozcetinkaya, S., Gokalp, P., Cetin, T., et al. (2012). Relationship between defense styles, alexithymia, and personality in alcohol-dependent inpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53, 860–867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.01.002

Fang, S., Chung, M. C., & Wang, Y. (2020). The impact of past trauma on psychological distress: The roles of defense mechanisms and alexithymia. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 992. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00992

Gaetan, S., Bréjard, V., & Bonnet, A. (2016). Video games in adolescence and emotional functioning: Emotion regulation, emotion intensity, emotion expression, and alexithymia. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.027

Guglielmucci, F., Monti, M., Franzoi, I. G., Santoro, G., Granieri, A., Billieux, J., & Schimmenti, A. (2019). Dissociation in problematic gaming: A systematic review. Current Addiction Reports, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-0237-z

Green, R., Delfabbro, P. H., & King, D. L. (2020). Avatar-and self-related processes and problematic gaming: A systematic review. Addictive Behaviors, 108, 106461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106461

Green, R., Delfabbro, P. H., & King, D. L. (2021). Avatar identification and problematic gaming: The role of self-concept clarity. Addictive Behaviors, 113, 106694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106694

Green, R., Delfabbro, P. H., & King, D. L. (2021). Player-avatar interactions in habitual and problematic gaming: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00038

Helmes, E., McNeill, P. D., Holden, R. R., & Jackson, C. (2008). The construct of alexithymia: Associations with defense mechanisms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(3), 318–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20461

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

International Test Commission (2005). International guidelines on test adaptation. www.intestcom.org. Accessed 22 May 2021.

Islas-Limón, J. Y., Aguirre-Ibarra, M. C., Viñas-Velázquez, B. M., Asadi-González, A. A., & Tovar-Hernández, D. M. (2019). Addiction as answer for the emptiness of identity. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 28(4), 522. https://doi.org/10.24205/03276716.2019.1127

Joreskog, K. G., & Sorbom, D. A. (2006). LISREL 8.54 and PRELIS 2.54. Scientific Software

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059

Király, O., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2015). Internet gaming disorder and the DSM-5: Conceptualization, debates, and controversies. Current Addiction Reports, 2(3), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0066-7

King, D. L., Delfabbro, P. H., Perales, J. C., Deleuze, J., Király, O., Krossbakken, E., & Billieux, J. (2019). Maladaptive player-game relationships in problematic gaming and gaming disorder: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 73, 101777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101777

Kline, R. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, third edition. Guildford Press

Kooiman, C. G., Spinhoven, P. H., Trijsburg, R. W., & Rooijmans, H. G. M. (1998). Perceived parental attitude, alexithymia and defense style in psychiatric outpatients. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 67(2), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1159/000012264

Landis, R. S., Beal, D. J., & Tesluk, P. E. (2000). A comparison of approaches to forming composite measures in structural equation modeling. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 186–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810032003

Leménager, T., Dieter, J., Hill, H., Hoffmann, S., Reinhard, I., Beutel, M., & Mann, K. (2016). Exploring the neural basis of avatar identification in pathological Internet gamers and of self-reflection in pathological social network users. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(3), 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.048

Leménager, T., Neissner, M., Sabo, T., Mann, K., & Kiefer, F. (2020). “Who Am I” and “How Should I Be”: A systematic review on self-concept and avatar identification in gaming disorder. Current Addiction Reports, 7(2), 166–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-020-00307-x

Li, D., Liau, A., & Khoo, A. (2011). Examining the influence of actual-ideal self-discrepancies, depression, and escapism, on pathological gaming among massively multiplayer online adolescent gamers. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(9), 535–539. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0463

Li, L., Niu, Z., Griffiths, M. D., Wang, W., Chang, C., & Mei, S. (2021). A network perspective on the relationship between gaming disorder, depression, alexithymia, boredom, and loneliness among a sample of Chinese university students. Technology in Society, 67, 101740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101740

Liew, L. W. L., Stavropoulos, V., Adams, B. L. M., Burleigh, T. L., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Internet Gaming Disorder: The interplay between physical activity and user–avatar relationship. Behaviour & Information Technology, 37, 558–574. https://doi.10.1080/0144929X.2018.1464599

McDougall, J. (1982). Alexithymia: A psychoanalytic viewpoint. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 38(1–4), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1159/000287617

Maganuco, N. R., Costanzo, A., Midolo, L. R., Santoro, G., & Schimmenti, A. (2019). Impulsivity and alexithymia in virtual worlds: A study on players of World of Warcraft. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of Treatment Evaluation, 16(3), 127–134

Monacis, L., Palo, V. D., Griffiths, M. D., & Sinatra, M. (2016). Validation of the internet gaming disorder scale–short-form (IGDS9-SF) in an Italian-speaking sample. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 683–690. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.083

Morganti, F., Rezzonico, R., Chieh Cheng, S., & Price, C. J. (2020). Italian version of the scale of body connection: Validation and correlations with the interpersonal reactivity index. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 51, 102400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102400

Parker, J. D. A., Taylor, G. J., & Bagby, R. M. (1998). Alexithymia: Relationship with ego defense and coping styles. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 39, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-440X(98)90084-0

Pickard, H. (2020). Addiction and the self Noûs. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12328

Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Measuring DSM-5 Internet Gaming Disorder: Development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.006

Price, C. J., & Thompson, E. A. (2007). Measuring dimensions of body connection: Body awareness and bodily dissociation. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 13(9), 945–953. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2007.0537

Price, A. L., Mahler, H., & Hopwood, C. (2019). Subjective emptiness: A clinically significant trans-diagnostic psychopathology construct. SocArXiv, 1–36 https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/f2x6r

Ratan, R. A., & Hasler, B. S. (2010). Exploring self-presence in collaborative virtual teams. PsychNology Journal, 8, 11–31

Ratan, R. A., & Dawson, M. (2016). When Mii is me: A psychophysiological examination of avatar self- relevance. Communication Research, 43(8), 1065–1093. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215570652

Schimmenti, A., & Caretti, V. (2010). Psychic retreats or psychic pits?: Unbearable states of mind and technological addiction. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 27(2), 115. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019414

Slater, M. D. (2007). Reinforcing spirals: The mutual influence of media selectivity and media effects and their impact on individual behavior and social identity. Communication Theory, 17, 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00296.x

Spada, M. M., & Caselli, G. (2017). The Metacognitions about Online Gaming Scale: Development and psychometric properties. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.007

Stavropoulos, V., Dumble, E., Cokorilo, S., Griffiths, M., & Pontes, H. M. (2022). The physical, emotional, and identity user-avatar association with disordered gaming: A pilot study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20, 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00136-8

Stavropoulos, V., Gomez, R., Mueller, A., Yucel, M., & Griffiths, M. (2020). User-avatar bond profiles: How do they associate with disordered gaming? Addictive Behaviors, 103, 106245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106245

Taylor, G. J., Bagby, M., & Parker, J. D. (1992). The Revised Toronto Alexithymia Scale: some reliability, validity, and normative data. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 57(1–2), 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1159/000288571

Wolfendale, J. (2007). My avatar, myself: Virtual harm and attachment. Ethics and Information Technology, 9(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-006-9125-z

Wu, A. M. S., Lei, L. L., & Ku, L. (2013). Psychological needs, purpose in life, and problem video game playing among Chinese young adults. International Journal of Psychology, 48(4), 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018

Zhang, M. X., Wang, X., Yu, S. M., & Wu, A. M. S. (2019). Purpose in life, social support, and internet gaming disorder among Chinese university students: A 1-year follow-up study. Addictive Behaviors, 99, 106070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106070

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Firenze within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Silvia Casale designed the study. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Alessia Musicò and Nicola Gualtieri. Silvia Casale and Giulia Fioravanti conducted the statistical analyses. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Silvia Casale, Giulia Fioravanti, Alessia Musicò. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Casale, S., Musicò, A., Gualtieri, N. et al. Developing an intense player-avatar relationship and feeling disconnected by the physical body: A pathway towards internet gaming disorder for people reporting empty feelings?. Curr Psychol 42, 20748–20756 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03186-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03186-9