Abstract

Curiosity is associated with a number of beneficial outcomes, such as greater life satisfaction, more work engagement and better academic performance. The connection between curiosity and beneficial outcomes supports the importance of examining whether it is possible to increase curiosity and to investigate what approaches may be effective in facilitating curiosity. This meta-analysis consolidated the effects of curiosity-enhancing interventions. Across 41 randomized controlled trials, with a total of 4,496 participants, interventions significantly increased curiosity. The weighted effect size was Hedges' g = 0.57 [0.44, 0.70]. These results indicated that interventions were effective across a variety of intervention principles used, with participants in various age groups, across various measures, and over different time periods. Interventions aiming to increase general curiosity showed larger effect sizes than interventions aiming to increase realm-specific curiosity. Interventions incorporating mystery or game playing had especially high effect sizes. Because higher levels of curiosity tend to be associated with various beneficial outcomes, the finding that across studies interventions are effective in increasing curiosity holds promise for future efforts to increase curiosity to bring about additional benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

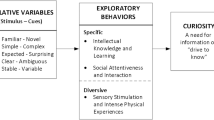

The objective of the present meta-analysis was to consolidate information regarding the possibility of enhancing curiosity through interventions. A central feature of curiosity is the desire to know (Vogl et al., 2020). Curiosity has affective, arousal, and expressive elements (Vogl et al., 2020), and is linked to cognition as well as to motivation. Curiosity is connected to cognition in that curiosity prompts seeking of information and expansion of cognitive capacity, including information processing and memory (Vogl et al., 2020). Curiosity is also a motivational force (Kobayashi et al., 2019; Vogl et al., 2020), driving pursuit of information. Curiosity can be both a momentary state as well as a more lasting trait (Silvia & Kashdan, 2009).

Beneficial Outcomes Related to Curiosity

Curiosity is a facet of wellbeing and is related to beneficial outcomes. For example, individuals higher in trait curiosity tend to show more growth-oriented behaviours, have a greater sense of meaning in life, and have higher life satisfaction (Kashdan & Steger, 2007). Higher levels of curiosity are associated with greater creativity (Schutte & Malouff, 2019a). A high level of state curiosity is associated with enhanced memory (Gruber et al., 2014). Work-related curiosity is associated with higher levels of work-related innovation (Celik et al., 2016) as well as greater job satisfaction and work engagement (Kashdanet al., 2020). In the educational realm, greater curiosity is related to better academic performance (Von Stumm et al., 2011).

Theoretical Conceptualisations of the Nature of Curiosity

There are several related theoretical conceptualisations of curiosity. Curiosity may have an evolutionary and biological basis that influences neural functioning related to seeking information (Bromberg-Martin & Monosov, 2020; Gottlieb et al., 2013). Curiosity can involve deprivation sensitivity, or wanting to avoid or eliminate lack of knowledge (Loewenstein, 1994), as well as desire for information for its own sake (Kashdan & Steger, 2007). Conceptualised as information seeking, curiosity itself can be influenced by the apparent value of obtaining information (Sharot & Sunstein, 2020). Curiosity may involve the desire to explore in ways that optimally increase the usefulness of information (Dubey & Griffiths, 2020). Based on this background, we conceptualised curiosity as an emotion tied to motivation to obtain information.

Interventions Intended to Increase Curiosity

The connection between curiosity and beneficial outcomes indicates the importance of establishing whether it is possible to increase curiosity and investigating what approaches are effective in facilitating curiosity. Specific conceptualisations of curiosity have been the basis for some programs intended to increase curiosity. For example, the conceptualisation of curiosity as wanting to know and that desire then prompting seeking of information is a foundation for interventions such as those implemented by Wright et al. (2018), which revealed new information step by step, leaving the next step of information to be revealed unknown. Such interventions draw on mystery surrounding information to pique curiosity.

Other interventions, such as in a study by Ortner and Zelazo (2014), have drawn on techniques such as mindfulness training, which induces non-judgmental awareness to increase curiosity. Such non-judgemental awareness may lessen distraction from thoughts and environmental impacts that interfere with the desire of wanting to know.

Building on mindfulness theory and research findings suggesting that curiosity can be an aspect of mindfulness (Siegling & Petrides, 2016), Chandrasiri et al. (2020) investigated the effect of a mindfulness intervention on curiosity and found that mindfulness training can have a beneficial impact. Schiefer et al. (2020) assessed the effect of an exploration and discovery program on curiosity and found this program to increase curiosity.

Studies have investigated various other approaches to increasing curiosity. These studies have used a variety of intervention methods and focused on specific populations. In discussing possible interventions intended to enhance curiosity, Kashdan and Fincham (2004) suggested that it would be useful to facilitate intrinsic motivation. Building on Kashdan and Fincham’s (2004) suggestion that intrinsic motivation might facilitate curiosity, Schutte and Malouff (2019b) investigated whether providing individuals with autonomy, which may be intrinsically motivating, in selecting a topic would lead to greater curiosity about the topic. The study found that autonomy support did increase curiosity in the intervention group participants compared to a control group of participants. However, a study reported by Arnone and Grabowski (1992) did not find that autonomy increased curiosity.

Curiosity intervention studies have focused on different populations. For example, Van der Horst and Klehe (2019) investigated how a work-related intervention influenced employee curiosity. Green et al. (2020) examined the effect of an intervention on career-related curiosity among students. Manotas (2012) examined the impact of an intervention on healthcare workers’ curiosity. Johns and Endsley (1977) investigated how modelling of curiosity affects children’s curiosity.

Some studies have investigated the impact of an intervention on a specific type of curiosity, such as about objects in a museum (Koran et al., 1984), while other studies have investigated the effect of an intervention on more general curiosity, such as desire for more knowledge (Schiefer et al., 2020). Some interventions such as the intervention used by Koran et al. (1984) have been brief, while others, such as the intervention by Green et al. (2020) that lasted four months, have been longer. Some interventions have assessed curiosity through self-reported curiosity, such as in the study reported by Gayner et al. (2012), while other interventions have assed curiosity through behaviour demonstrating curiosity, such as in an intervention reported by Ruan et al. (2018).

Studies focused on increasing curiosity through interventions have found varying results. Thus, the overall effect across studies of the impact of attempts to increase curiosity is not known. A meta-analysis can consolidate the findings of studies investigating increasing curiosity.

Conceptual elements underlying curiosity interventions, such as whether curiosity is induced through mystery, or mindfulness, or autonomy, may influence the differential impact of interventions. Thus, type of intervention may be a moderator that accounts for differences between interventions. Whether resulting curiosity is assessed regarding a specific realm of life or as curiosity in general may also account for differences effect sizes between studies, and thus be a moderator. Developmental stage of participants, operationalised by whether participants were adults or children, may further account for differences in effect sizes between studies and may thus be a moderator. Finally, the various lengths of interventions employed by different studies and whether curiosity was assessed through self-report or a behavioural outcome may be moderators accounting for differences between studies.

Aim of the Present Study

The main aim of this meta-analytic study was to consolidate results of studies using randomized assignment of participants to intervention conditions and control conditions to investigate the impact of interventions on curiosity. Even though within-group pre-post studies and quasi-analytic studies can be informative, they tend to have more confounds than random-assignment studies. Studies using a random-assignment design tend to result in clearer evidence regarding causality (Coolican, 2017). Studies focusing on increasing curiosity have been based on a variety of participants, including children and adults in various circumstances. Because curiosity may have a similar foundation across individuals (Zurn & Bassett, 2018), a weighted overall effect size of the results of studies with a variety of participants can be informative. Consolidating results of studies that aimed to increase curiosity and identifying moderators that may influence the success of curiosity interventions could help guide the development of future interventions intended to boost curiosity.

Our hypothesis was that across studies interventions would increase curiosity. A related aim of the meta-analytic study was to examine potential moderators of the effect size across studies. We had no specific hypotheses regarding these moderators. The exploratory moderator analyses focused on the principle underlying the intervention (for example, whether mystery was involved), whether the intervention was brief or longer, whether curiosity targeted was general curiosity or curiosity for a specific realm, whether participants were adults or children, and whether curiosity was assessed through self-report or behaviour.

Method

The inclusion criteria for studies were that they 1) compared an intervention condition with a control condition using random assignment of participants to conditions (RCTs); 2) assessed curiosity in both groups before and after the intervention or assessed curiosity in both groups after the intervention; and 3) provided sufficient statistical results for the calculation of an effect size. We included only RCTs because they provide the most stringent way to evaluate treatment efficacy (American Psychological Association, 2002; p. 1054).

We searched the databases EBSCO (education, business, nursing, science, psychology and philosophy), PsycInfo (behavioural sciences and mental health), and ProQuest Social Science (education, sociology, linguistics, and criminal justice) using the terms curio*, AND intervention OR experiment OR trial OR increas* OR impact* OR influe* OR effect*, searching for these terms in abstracts and subject terms. We also searched the reference lists of articles relating to curiosity for possible other studies for inclusion. Finally, where possible, we wrote to the corresponding authors of articles related to curiosity intervention studies to ask whether they knew of relevant unpublished studies. The search concluded in November 2020. A follow-up search in March, 2022, showed no additional studies to include. Figure 1 shows the search process and the number of resulting studies. The search resulted in identification of numerous publications that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Examples include review articles that mentioned curiosity and interventions, but did not provide effect sizes, articles that described studies that did not use random assignment to conditions, and articles that mentioned curiosity but did not assess curiosity. The search resulted in identification of 41 samples that met the criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis. We used the traditional, conservative method of using actual effect sizes of studies with no adjustment for imperfect reliability of measures.

Table 1 provides details regarding the included studies. Some studies included multiple samples. The 41 samples included in the meta-analysis had a total of 4,496 participants.

For each sample, the following information was entered: 1) the name of the study and specific sample from the study if there were results from multiple samples reported in an article, 2) the number of participants in the sample, 3) the effect size for the impact of the intervention on curiosity, (4) the psychological principle underlying the intervention, (5) the type of sample (children or adults), 6) whether curiosity was about a specific matter or was general curiosity, 7) whether the curiosity assessment was by self-report or behaviourally based, and 8) whether the intervention was brief (within one day) or longer.

The type of principle was based on curiosity literature and an initial scan of types of principles underlying interventions. Principles included 1) providing participants with autonomy or choice, which relates to intrinsic motivation (Kashdan & Fincham, 2004), 2) creating mystery, which relates to structuring material or situations to stimulate interest in the unknown (Kashdan & Fincham, 2004), 3) training mindfulness, related to the proposition that curiosity is an aspect of mindfulness (Siegling & Petrides, 2016), and 4) other, a category that included principles such as modeling curiosity that were used rarely in the studies. Some descriptive details of the studies were also recorded.

Principles underlying interventions were operationalized in various ways in different studies. Following are examples of operationalization of mystery, game-playing and mindfulness. In a mystery-creating intervention, Ruan et al. (2018) showed participants photos of scenes in major cities and asked them to guess which city was shown in each. In a game-playing intervention, Müller-Stewens et al. (2017) asked participants in the experimental condition to ride a bicycle in a realistic video game. Ortner and Zelazo (2014) used a mindfulness intervention in which they asked participants in the experimental condition to spend 10 min attending to their breathing, the present moment, and their thoughts and feelings. Even though the operationalisation of principles related to increasing curiosity differed between studies, the independent reliability coding of the raters, as detailed below and which was based on the conceptual nature of the principles, indicated that studies could be grouped according to underlying principles.

Coding samples as consisting of children or adults was based on the notion that there may be developmental differences in curiosity (Beiser, 1984). Coding of specific versus general curiosity was based on both of these manifestations having been identified theoretically and empirically (Silvia & Kashdan, 2009). General curiosity consists of a desire for more information of many kinds. Specific curiosity consists of a desire for more information regarding a specific matter, such as wanting to obtain more knowledge about a certain culture. Measures of curiosity varied and depended on the context of the study. Self-report measures included ones such as the widely used curiosity subscale of the Toronto Mindfulness Inventory (e.g., Chandrasiri et al., 2020) and subscales of the Five Dimensional Curiosity Inventory (e.g., Schutte (2020). Behavioural measures included ones such as neuroimaging of brain activation thought to be related to curiosity (e.g., van Lieshout et al. (2018). Coding the intervention as brief or longer was based on the notion that interventions of different length might influence how participants absorb and consolidate aspects of the intervention.

In some cases an included article provided the total N but not the n per condition. When necessary, we estimated that the split was even or randomly assigned one condition to have one more participant than the other. The corresponding author for Wright et al. (2018) provided us with the exact n for each condition.

Reliability of coding was assessed through an inter-rater reliability check. A sample of 30 percent of the entries was checked by an independent coder who did not have access to the original coding, a standard approach to estimating inter-rater reliability in meta-analyses. (Park & Kim, 2015). Inter-rater agreement was 95%. Coding on which there was not agreement was discussed and resolved through further review of the studies. The data set resulting from the coding is available at https://rune.une.edu.au/web/handle/1959.11/29807.

Results

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3.3 (CMA; Borenstein et al., 2014) calculated the overall weighted effect size for the effect of interventions on curiosity. The effect size was expressed as Hedges’ g. The CMA software also performed moderator analyses and publication bias analyses.

The Effect Size of Curiosity Interventions Across Studies

Hedges’ g, which corrects for a bias in Cohen’s d and is therefore generally preferred by statistics experts (Lakens, 2013), assessed the impact of interventions on curiosity. Across 41 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a total of 4,496 participants, including adults and children, interventions significantly increased curiosity. Hedges' g was 0.57 [0.44, 0.70], p < 0.001. Figure 2 shows the forest plot, which provides information regarding each individual study and the variation between studies.

The funnel plot indicated that the effect sizes were somewhat asymmetrically distributed. Figure 3 shows the funnel plot. Duvall and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis addressed this asymmetry of effect sizes. Duvall and Tweedie's trim and fill found evidence of bias regarding Small N studies and suggested eliminating five studies. After eliminating those studies, the effect change fell to 0.49 [0.36, 0.62], p < 0.001. The Hedges’ g of 0.49 still represented a roughly moderate effect size.

Moderator Analyses

Moderator analyses showed significantly higher effect sizes for interventions aimed at increasing general curiosity than for those aimed at increasing specific curiosity, but there were only two studies in the general-curiosity category. Some meta-analysis experts recommend a minimum of 10 studies in each moderator category, but other experts give approval to lower numbers such as 2 (Pincus et al., 2011).

The other potential moderators were all non-significant: type of intervention, length of intervention, self-report for curiosity versus behavioural indicator, or type of participant. However, there were signs of higher effects sizes for longer interventions and for interventions involving mystery, game playing, and types of interventions other than autonomy and mindfulness. Table 2 shows the moderator results.

Several studies showed especially large effect sizes. These studies were as follows. Ruan et al. (2018) created uncertainty in an interesting matter. In two studies, van Lieshout et al. (2018) also induced uncertainty. Green et al. (2020) offered participants in the intervention condition a course focused on developing proactive and adaptation skills. Isikman et al. (2016) primed curiosity through questions. Lenehan et al. (1994) provided students with material that matched their learning style preferences. The large effect sizes found in these studies may indicate the value of the intervention strategies used in the studies.

Discussion

The objective of the present study was to consolidate information regarding whether interventions can enhance curiosity. Across 41 randomized controlled trials, with a total of 4,496 participants, interventions significantly increased curiosity. The weighted effect size, reported as Hedges' g, of 0.57 (0.49 adjusted) indicates a moderate effect of interventions. The effect size is based on studies using various principles to increase curiosity and participants from various populations. This finding supported the hypothesis that across studies, interventions would increase curiosity.

Theoretical Implications

The confirmation that curiosity can be increased and the findings regarding some of the specific aspects of interventions intended to increase curiosity have implications for theories regarding the nature of curiosity. For example, the robust effect size for interventions drawing on mystery provides some support for information-processing related theories of curiosity. The higher effect size for studies that aimed to increase general curiosity versus those that aimed to increase realm-specific curiosity may support the value of consideringassessing these aspects of curiosity as somewhat distinct constructs.

Practical Implications

The finding that across studies, curiosity was increased through interventions supports the potential of programs intended to raise curiosity as an end goal. The finding also supports the potential of programs that seek to raise curiosity to obtain related effects such as increases in creativity (Schutte & Malouff, 2019a), innovation (Celik et al., 2016), life satisfaction (Kashdan & Steger, 2007), life meaning, academic performance (Von Stumm et al., 2011), and job satisfaction (Kashdan et al., 2020). In such research the increases in curiosity can then be viewed as a manipulation check of the intended impact of the intervention. An example of this process of other benefits possibly being stimulated by increasing curiosity is the finding by Schutte (2020) that as well as increasing curiosity, an intervention increased positive affect and experience of engagement, and that the increase in curiosity was related to the amount of increase in positive affect and flow.

One potential moderator showed a significant association with effect size: Studies that aimed for increases in general curiosity had bigger effect sizes than studies that aimed to increase specific curiosity, e.g., regarding the outcome of a specific matter or activity. However, there were only two studies that targeted general curiosity, Lenehan et al. (1994) and Schiefer et al. (2020), and both studies had lengthy interventions. Hence, the meaning of the significant moderation is ambiguous.

In the present study, potential moderators relating to curiosity intervention principle, length of intervention, self-report for curiosity versus behavioural indicator, or type of participant were not significant. The lack of significance of these moderators suggests that interventions are relatively robust in regard to variation in these moderator variables. It may be that multiple approaches to increasing curiosity are effective. This idea is supported by the strong effect sizes for interventions drawing on mystery, providing game play, and providing a collection of “other” methods to stimulate curiosity. Interventions drawing on enhancing mindfulness or autonomy did not have a significant effect across studies, although some individual studies found positive effects.

If the conceptualisation of curiosity is the desire to know, interventions such as those that present a mystery in relation to which individuals can not immediately access information may be especially effective in piquing curiosity. A practical implication is that interventions that emphasise what an individual does not know or challenges an individual to obtain new knowledge or test new skills may be most effective. Such interventions would have relevance in various areas, including education and organisational settings.

There was no significant difference between studies classified according to age, but the effect sizes for adults were especially high. A practical implication is that interventions aiming to enhance curiosity in children may require different approaches from some of the ones already investigated. There was no significant meta-analytic difference across shorter interventions of one day or less and longer interventions. However, the large effect size of g = 0.78 for longer interventions is notable, and as more curiosity enhancing interventions are studied, length of intervention may emerge as instrumental in increasing curiosity. A practical implication of the large effect size found for longer intervention is that, when possible, it may be beneficial to design longer more in-depth interventions. Curiosity self-report measures and behavioural measures of curiosity showed similar effect sizes across studies. This finding may indicate that individuals have reasonable insight into their experience of curiosity and that behaviours prompted by curiosity reflect the subjective experience of curiosity.

Limitations

Limitations of the present meta-analysis include the availability of only a small number of studies with features that allowed inclusion in some of the moderator categories. For example the moderator analysis focusing on type of curiosity, general or specific, compared 39 to 2 studies. Findings regarding the significance of these moderators may change as more studies are conducted. The reliability of curiosity outcome measures may have influenced the results. Adjusting for reliability of outcome measures may result in larger effect sizes, but some researchers point out that this approach may inaccurately inflate the size of findings (Podsakoff et al., 2012). The 95% agreement rate between coders of the data used in the meta-analysis provides a level of confidence in the coding process, similar to a reliability of 0.95 for a scale providing confidence in the reliability of a scale. Nevertheless, there may be slight variations from true effect sizes or moderator impacts related to reliability of coding.

Future Research

Future research investigating the effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing curiosity might examine other principles that could help formulate intervention approaches. For example, drawing on the notion that curiosity is a motivating emotion that includes cognitive aspects, researchers could tailor intervention activities to individuals’ prominent motivations or cognitions in order to stimulate curiosity in a topic or activity. Future research might also investigate how to best harness principles, such as introduction of mystery, that seem to lead to strong effects for interventions. Future research might further investigate the linkages between curiosity increased through interventions and how this increase in curiosity impacts other beneficial outcomes. Researchers could explore further the effects of interventions intended to increase general curiosity, including ensuing effects, such as on learning, grades, and positive affect. Researchers could also explore various unknowns, such as which methods work best to increase curiosity in head-to-head comparisons and how long effects last.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis consolidated the effects of curiosity enhancing interventions. Across 41 studies, which included 4,496 participants, interventions significantly increased curiosity. Interventions introducing mystery and using games to increase curiosity were especially effective. The finding that curiosity can be systematically increased is promising because higher levels of curiosity tend to be associated with various beneficial outcomes. Because it is possible to increase curiosity with certain methods, teachers, parents, marketers, and others could employ such methods. Increases in curiosity may then also lead to changes in other characteristics, such as creativity.

References

Studies with an asterisk were included in the meta-analysis.

American Psychological Association. (2002). Criteria for evaluating treatment guidelines. American Psychologist, 57, 1052–1059. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.12.1052

*Arnone, M. P., & Grabowski, B. L. (1992). Effects on children’s achievement and curiosity of variations in learner control over an interactive video lesson. Educational Technology Research and Development, 40(1), 15–27.

Beiser, H. R. (1984). On curiosity: A developmental approach. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 23(5), 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60341-1

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2014). Comprehensive meta-analysis (Version 3) [computer software]. Biostat.

Bromberg-Martin, E. S., & Monosov, I. E. (2020). Neural circuitry of information seeking. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 35, 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.07.006

*Cabral-Marquez, C. (2011). The effects of setting reading goals on reading motivation, reading achievement, and reading activity (Doctoral dissertation, Northern Illinois University). https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1332

Celik, P., Storme, M., Davila, A., & Myszkowski, N. (2016). Work-related curiosity positively predicts worker innovation. Journal of Management Development, 35(9), 1185–1194. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-01-2016-0013

*Chandrasiri, A., Collett, J., Fassbender, E., & De Foe, A. (2020). A virtual reality approach to mindfulness skills training. Virtual Reality, 24(1), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-019-00380-2.

Coolican, H. (2017). Research methods and statistics in psychology. Psychology Press.

Dubey, R., & Griffiths, T. L. (2020). Reconciling novelty and complexity through a rational analysis of curiosity. Psychological Review, 127, 455–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000175

*Gayner, B., Esplen, M. J., DeRoche, P., Wong, J., Bishop, S., Kavanagh, L., & Butler, K. (2012). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to manage affective symptoms and improve quality of life in gay men living with HIV. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 35(3), 272–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-011-9350-8.

Gottlieb, J., Oudeyer, P. Y., Lopes, M., & Baranes, A. (2013). Information-seeking, curiosity, and attention: Computational and neural mechanisms. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17, 585–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.09.001

*Green, Z. A., Noor, U., & Hashemi, M. N. (2020). Furthering proactivity and career adaptability among university students: Test of intervention. Journal of Career Assessment, 28(3), 402–424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072719870739.

Gruber, M. J., Gelman, B. D., & Ranganath, C. (2014). States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron, 84(2), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.060

*Hill, K. M., Fombelle, P. W., & Sirianni, N. J. (2016). Shopping under the influence of curiosity: How retailers use mystery to drive purchase motivation. Journal of Business Research, 69(3), 1028–1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.015.

*Isikman, E., MacInnis, D. J., Ülkümen, G., & Cavanaugh, L. A. (2016). The effects of curiosity-evoking events on activity enjoyment. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 22(3), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000089.

*Johns, C., & Endsley, R. C. (1977). The effects of a maternal model on young children’s tactual curiosity. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 131(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1977.10533268.

Kashdan, T. B., & Fincham, F. D. (2004). Facilitating Curiosity: A Social and Self-Regulatory Perspective for Scientifically Based Interventions. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Applied positive psychology: A new perspective for professional practice. Wiley.

Kashdan, T. B., & Steger, M. F. (2007). Curiosity and pathways to well-being and meaning in life: Traits, states, and everyday behaviors. Motivation and Emotion, 31(3), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-007-9068-7

Kashdan, T. B., Goodman, F. R., Disabato, D. J., McKnight, P. E., Kelso, K., & Naughton, C. (2020). Curiosity has comprehensive benefits in the workplace: Developing and validating a multidimensional workplace curiosity scale in United States and German employees. Personality and Individual Differences, 155, 109717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109717

Kobayashi, K., Ravaioli, S., Baranès, A., Woodford, M., & Gottlieb, J. (2019). Diverse motives for human curiosity. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(6), 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0589-3

*Koran, J. J., Jr., Morrison, L., Lehman, J. R., Koran, M. L., & Gandara, L. (1984). Attention and curiosity in museums. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 21(4), 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660210403.

Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 863. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863/full

*Lenehan, M. C., Dunn, R., Ingham, J., & Signer, B. (1994). Effects of learning-style intervention on college students’ achievement, anxiety, anger, and curiosity. Journal of College Student Development, 35(6), 461–466.

Loewenstein, G. (1994). The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 75. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.75

*Manotas, M. A. (2012). Brief mindfulness training to improve mental health with Colombian healthcare professionals. California Institute of Integral Studies.

*Mehta, H., Dubey, R., & Lombrozo, T. (2018). Your liking is my curiosity: a social popularity intervention to induce curiosity. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. https://cognition.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/cognition/files/mehta.pdf

*Müller-Stewens, J., Schlager, T., Häubl, G., & Herrmann, A. (2017). Gamified information presentation and consumer adoption of product innovations. Journal of Marketing, 81(2), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0396.

*Nasser, J. D., & Przeworski, A. (2017). A comparison of two brief present moment awareness training paradigms in high worriers. Mindfulness, 8(3), 775–787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0656-z.

*Ortner, C. N., & Zelazo, P. D. (2014). Responsiveness to a mindfulness manipulation predicts affect regarding an anger-provoking situation. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement, 46(2), 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029664.

Park, C. U., & Kim, H. J. (2015). Measurement of inter-rater reliability in systematic review. Hanyang Medical Reviews, 35(1), 44–49. https://synapse.koreamed.org/articles/1044249

Pincus, T., Miles, C., Froud, R., Underwood, M., Carnes, D., & Taylor, S. J. (2011). Methodological criteria for the assessment of moderators in systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials: A consensus study. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-14

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

*Potts, R., Davies, G., & Shanks, D. R. (2019). The benefit of generating errors during learning: What is the locus of the effect? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 45(6), 1023–1041. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000637.

*Ruan, B., Hsee, C. K., & Lu, Z. Y. (2018). The teasing effect: An underappreciated benefit of creating and resolving an uncertainty. Journal of Marketing Research, 55(4), 556–570. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.15.0346.

*Sääksjärvi, M., Gill, T., & Hultink, E. J. (2017). How rumors and preannouncements foster curiosity toward products. European Journal of Innovation Management, 20(3), 350–371. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-03-2016-0037.

*Schiefer, J., Golle, J., Tibus, M., Herbein, E., Gindele, V., Trautwein, U., & Oschatz, K. (2020). Effects of an extracurricular science intervention on elementary school children's epistemic beliefs: A randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), 382–402. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304395910003301

*Schutte, N. S. (2020). The impact of virtual reality on curiosity and other positive characteristics. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 36(7), 661–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2019.1676520.

Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2019a). A meta-analysis of the relationship between curiosity and creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior. Early view at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/jocb.421. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.421

*Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2019b). Increasing curiosity through autonomy of choice. Motivation and Emotion, 43(4), 563–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09758-w.

Sharot, T., & Sunstein, C. R. (2020). How people decide what they want to know. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 14–19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0793-1

*Sharpe, L., Nicholson Perry, K., Rogers, P., Refshauge, K., & Nicholas, M. K. (2013). A comparison of the effect of mindfulness and relaxation on responses to acute experimental pain. European Journal of Pain, 17(5), 742–752. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00241.x.

Siegling, A. B., & Petrides, K. V. (2016). Zeroing in on mindfulness facets: Similarities, validity, and dimensionality across three independent measures. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0153073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153073

Silvia, P. J., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Interesting things and curious people: Exploration and engagement as transient states and enduring strengths. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(5), 785–797. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00210.x

*Thomas, V. L., & Vinuales, G. (2017). Understanding the role of social influence in piquing curiosity and influencing attitudes and behaviors in a social network environment. Psychology & Marketing, 34(9), 884–893. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21029.

Van der Horst, A. C., & Klehe, U. C. (2019). Enhancing career adaptive responses among experienced employees: A mid-career intervention. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 111, 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.08.004.

*van Lieshout, L. L., Vandenbroucke, A. R., Müller, N. C., Cools, R., & de Lange, F. P. (2018). Induction and relief of curiosity elicit parietal and frontal activity. Journal of Neuroscience, 38(10), 2579–2588. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2816-17.2018.

Vogl, E., Pekrun, R., Murayama, K., & Loderer, K. (2020). Surprised–curious–confused: Epistemic emotions and knowledge exploration. Emotion, 20(4), 625–641. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000578

Von Stumm, S., Hell, B., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2011). The hungry mind: Intellectual curiosity is the third pillar of academic performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 574–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611421204

*Wright, S. A., Clarkson, J. J., & Kardes, F. R. (2018). Circumventing resistance to novel information: Piquing curiosity through strategic information revelation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.12.010.

Zurn, P., & Bassett, D. S. (2018). On curiosity: A fundamental aspect of personality, a practice of network growth. Personality Neuroscience, 1, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/pen.2018.3

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions The project received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent

As this study is a meta-analysis not directly involving participants, informed consent was not relevant.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schutte, N.S., Malouff, J.M. A meta-analytic investigation of the impact of curiosity-enhancing interventions. Curr Psychol 42, 20374–20384 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03107-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03107-w