Abstract

The goal is to test the validity of the “Will to exist-live and survive (WTELS) as a master motivator that activates executive functions. A sample of 262 adults administered different measures that included WTELS and executive functions. We conducted hierarchical regressions with working memory deficits (WMD) and inhibition deficits (ID) as dependent variables. We entered in the last steps resilience and WTELS as independent variables. We conducted path analysis with WTELS as independent variables and WMD and ID as outcome variables and resilience and social support as mediating variables. WTELS accounted for the high effect size for lower working memory deficits and medium effect size for lower inhibition deficits. In path analysis, the effects of WTELS on decreased WMD were direct, while its effects on the ID were indirect. PROCESS analysis indicated that WTELS was directly associated with lower depression, anxiety, PTSD, and COVID-19 traumatic stress, and its indirect effects were mediated by lower executive function deficits (Kira et al., Psych 12:992-1024 2021c, Kira et al., in press). The path model discussed was generally superior to the alternative models and was strictly invariant across genders (male/ female).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Will (and volition) to exist live and survive (WTELS) is proposed recently in the literature as a master intrinsic positive motivator (or meta-motivator) (Kira, Özcan, Shuwiekh, et al., 2020a; Kira, Shuwiekh, Kucharska, et al., 2020b). Will or volition comprises various mechanisms that are needed to obtain predefined goals (Corno & Kanfer, 1993). The will to exist (WTE) represents the agency and the executive self. WTE is the principal part of WTELS. “Exist” is being used here narrowly as persistent existential striving rather than more broadly as striving or enduring. Will or volition, a pre-cognitive process related to agency and executive action control (executive self), found to contribute toward academic achievement above and beyond cognitive and personality factors (Haggard, 2017; Schlüter et al., 2018). A study found that the will to survive (WTS), another core part of WTELS, to be key to different coping strategies to continuous traumatic stress of oppression (Kira, Alawneh, et al., 2014a).

Will to live (WTL), Hutschnecker, 1951, another essential dimension of WTELS, has been defined as “the psychological expression of one’s commitment to life and the desire to continue living,” encompass both instinctual (motivational) and cognitive components. Bornet et al., 2020, in a review, found that WTL in the reviewed studies was positively associated with resilience (r = 0.63), life satisfaction (r = 0.55), happiness (r = 0.48), purpose in life (r = 0.42), quality of life (r = 0.51) and self-rated health (r = 0.45), functional status (r = 0.36) and the presence of social contacts (r = 0.47). They found that WTL to be associated negatively with the wish to die (r = −0.81), suicidal intent (r = −0.76), depressive symptoms (r = −0.63), and feeling of being a burden to others (r = −0.61).

While WTE is related to the existence of the executive self that asserts itself in a constant search for meaning and a meaningful place and status, WTL is related to commitment to life and the desire to continue living, and WTS is related to dealing with and surviving adversities and traumas. WTS is especially important when dealing with severe and continuous trauma such as early childhood adversities, discrimination, oppression, and COVID-19 traumatic stress. For example, surviving early childhood trauma is associated with increased vulnerability to suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury (Serafini et al., 2017a, b), which needs a strong will to survive. WTS is also crucial to minorities in surviving oppression and discrimination (Kira, Alawneh, et al., 2014a). Targeting the nurturing and optimizing of WTS for victims of severe and continuous traumas may help prevention and intervention strategies. WTE, WTS, and WTL, while present different dimensions of the person’s venture, are proved to connect as powerful master motivation in the unidimensional construct of WTELS (Kira, Özcan, Shuwiekh, et al., 2020a). WTE, WTS, and WTL are overlapping distinct constructs that have been tested as a one-factor model.

WTELS is the intrinsic, innate motivation to exist, live, survive, self-actualize, and succeed/ thrive (Kira, Shuwiekh, Kucharska, et al., 2020b, p.48). WTELS propels and manages goal-directed activities and their hierarchy of motivational architecture in different challenges and life projects. WTELS is an existential feature that is part of the person’s agentic executive self (Kira, Lewandowski, et al., 2014b). WTELS, a non-cognitive (or pre-cognitive) factor, has cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and mental health consequences. WTELS is a powerful tool when it comes to the understanding of dynamics that are at the center stage in the science of motivation and coping with adversities. These dynamics include WTELS’s role in mental and physical health, post-traumatic growth (PTG), resilience, seeking, and providing social support. The empirical research found compelling evidence that WTELS is strongly associated with PTG, resilience, and social support (Kira, Özcan, Shuwiekh, et al., 2020a).

Eren-Koçak and Kiliç (2014) found PTG to be associated with improved executive functions (EF) and that EF may enable PTG. A study found that resilience is associated with improved EF (Wu et al., 2021). Also, the research found that social support has a positive influence on cognitive functioning and buffers cognitive decline in older adults (Sims et al., 2011). Research demonstrates that middle-aged and older adults’ social media use for social connection can be a helpful medium that protects against age-related decline in EF (Khoo & Yang, 2020).

The WTELS, as a consciously and unconsciously controlled motivational processes and dynamics, may fluctuate in its vigor with age and differ with gender (e.g., Carmel, 2001). The motivational processes were long associated neurologically with EF especially working memory (e.g., Taylor et al., 2004), and theoretically was long associated with executive control (inhibition) (e.g., Pessoa, 2009). Motivation gradients have been shown to modulate attentional processes in many perceptual and cognitive control fields (for reviews, see Pessoa, 2009; Pessoa and Engelmann, 2010). For our brains to activate our executive skills required to take purposeful action, a motivational force is required. The more motivation the person may have, the more activation/ mobilization and maximization of his/ her available cognitive skills. If the motivation ceased or depleted, the brain can slow down or get stuck in a state of inaction. Empirical and experimental research provided evidence that conscious and unconscious implicit stimulation of motivation resulted in improved EF (e.g., Cohen-Zimerman & Hassin, 2018).

At the behavioral level, motivation impacts the dynamics of cognitive control on both short and long timescales. Research on cognition and executive function has long recognized the interface of motivation and working memory and cognitive control. The function of cognitive control and working memory capacity is driven, powerfully and fundamentally, by the desires, goals, and other motivational and meta motivational factors (Braem et al., 2013; Engelmann et al., 2009; Fröber & Dreisbach, 2014; Leotti & Wager, 2010; Libby & Lipe, 1992; Locke & Braver, 2008; Padmala & Pessoa, 2011; Pessoa, 2009; Savine et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2004). The primacy of volition and motivation emphasizes that cognition, emotion, agency, and other psychological processes exist to serve volition and motivation with volition as the control processes that regulate them (Baumeister, 2016; Mischel & Ayduk, 2011; Stolorow & Atwood, 2014).

At the neurological level, the available data strongly suggest that the relationship between motivation and control reflects itself in the interactions between two large-scale brain networks, one centrally involved in representing reward value and the other involved in implementing control function. There is evidence that striatal dopamine mediates the interface between motivational and cognitive control in humans (Aarts et al., 2010). Several neural structures, including dopaminergic projections, ventral striatum, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (PFC), lateral PFC, and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), appear to serve as critical channels for control-relevant motivational signals (for review see Botvinick & Braver, 2015).

Additionally, previous studies indicated that WTELS is associated with improved mental health (e.g., Kira, Özcan, Shuwiekh, et al., 2020a). The question is how much of this improvement is due to its direct motivational positive impact and how much improvement may be mediated by potential improved executive functions, or resilience, and social support. Conversely, severe psychopathology can reverse the dynamics and negatively affect WTELS, such as increasing suicidality and the desperate desire to get out of existence.

The current study aims to test if WTELS as a master motivator has significant positive effects on EFs. That never has been explored before and can have significant conceptual and clinical implications. The study will further validate the WTELS construct as a master motivator that interfaces with executive function. That is especially important for the relationship between will and volitional motive to exist and executive self. It also targets to explore if the executive functions mediate some of the WTELS positive impacts on mental health.

-

Hypothesis 1:

WTELS as a master motivator has a significant linear association with lower working memory and inhibition deficits.

-

Hypothesis 2:

Lower inhibition and working memory deficits will mediate the indirect effects of WTELS on lower PTSD, depression, anxiety, and COVID-19 traumatic stress, in addition to its potential direct effects on them.

-

Hypothesis 3:

The model that details the paths of effeects is invariant across genders.

Methods

Participants

Age ranged from 18 to 73 (Mean = 28.25, SD = 10.35), with70.6% males. For work, 51.9% students,15.3% work with the government, 17.6% work in the private sector, 13.7% unemployed, and 1.5% retired. For marital status, 23.7% were married, 74.8% single, 1.1% were divorced, and .4% were widowed. For socioeconomic status (SES), 3.4% indicated that they belong to very low SES, 9.2% reported they belong to low SES, 75.2% to middle SES, while 11.8% reported belonging to high SES, and .4% to a very high SES. For religion, 88.9% were Muslims, and 11.1% reported other religions. For education, 1.1% have read and write proficiency, 13% have an intermediate level of education, 79.4% have college or university education, and 6.5% have graduate degrees.

Procedures

We conducted this cross-sectional study from 2 October to 13 November 2020. We collected the data from 262 Turkish-speaking participants via a web-based self-report survey (Google Forms®). We used the snowball recruiting method to increase participation through social media (e.g., Facebook) and e-mail lists, mainly from North Cyprus, Mersen, and Adana’s cities in mainland Turkey. Participants were asked to complete a set of measures in the survey. Before filling the survey, we give information about the study’s purpose, and they have had to sign the online informed consent if they opted to participate. Inclusion criteria for participation in the study were: (a) being older than 18 years old and (b) consent to participate. We did not provide a reward the participation. The Ethics Committee of the sponsored University approved the study.

Measures

The “will-to-exist, live and survive” (WTELS) Scale

(Kira, Özcan, Shuwiekh, et al., 2020a; Kira, Shuwiekh, Kucharska, et al., 2020b). WTELS scale is a 6-item scale that measures different aspects of will to exist, live, survive, and thrive. It includes items such as “I am motivated by a drive to live”; “My will to exist and survive adversity is generally high.” We scored each item on a 5-point scale: 4 = very strong, 3 = strong, 2 = neutral, 1 = drained/depleted, 0 = extremely depleted/I have no will to survive. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses found that the measure has a one-factor structure. The measure’s one-factor structure was strictly invariant across gender, cultural, and religious groups. We should clarify that the WTELS scale is a short parsimonious measure, which did not allow robust testing of the three distinct unique components structure. WTELS construct is comprised of three distinct but overlapping components. A three-factor model was not established or tested because it was a short instrument consisting of only six items (a longer test allows at least four items per dimension).

Additionally, the study found that the measure’s test-retest stability coefficient (4 weeks interval) on a sample (N = 34) to be .82. WTELS has good convergent, divergent, and predictive validity. WTELS predicted a decrease in existential anxiety, mental health symptoms, and an increase in emotion regulation (reappraisal), self-esteem, and posttraumatic growth (Kira, Shuwiekh, Kucharska, et al., 2020b). The Cronbach’s reliability of the scale in current data is. 91.

Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) 10-Item Version (Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007; Connor & Davidson, 2003). The participant rates each item on a 5-point scale, with responses from not true at all (0) to true nearly all times (4). The total score ranges from 0 to 50. The original measure showed adequate internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent and divergent validity (Connor & Davidson, 2003). The short version CD-RISC-10 showed the same original version’s psychometrics (Scali et al., 2012). In our sample, the CD-RISC-10 showed adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

Social Support Survey (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991) is a 12-item scale and consists of two subscales: Emotional/ Informational Support (8 items) and Tangible Support (4 items). The participant rates each item on a 5-point scale, with (1) means none of the time, and (5) indicates all of the time. Multitrait scaling analyses supported the structure of four functional support dimensions: emotional/ informational, tangible, affectionate, and positive social interaction. The measure proved to have good reliability and pretty stable over time (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991). It has α = 0.93 in the current study.

The Adult Executive Functioning Inventory (ADEXI; Holst & Thorell, 2018) was used to investigate executive functioning deficits. The ADEXI is a 14-item scale that measures working memory deficits (9 items) (e.g., “I have difficulty remembering lengthy instructions” and inhibition deficits (5 items) (e.g., “I tend to do things without first thinking about what could happen”). The participant is asked to rate the statement on a scale from 1 to 5, with “1” indicates that it is definitely not true, and “5” indicates it is definitely true. A higher score indicates higher deficits and a lower score indicates lower deficits. The ADEXI was explicitly developed to investigate deficits in working memory and inhibition and address the limitations of other rating instruments of executive functioning that often include items overlapped with ADHD symptom levels. This instrument has proven to discriminate well between adults with ADHD and controls (Holst & Thorell, 2018). Alpha in current data is .87 for working memory deficits and .73 for inhibition deficits subscales.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL- V Blevins et al., 2015). PCL-V is a 20-item self-report measure. Each item is scored on a five-point scale with “0,” indicating “not at all” and 4 indicating “extremely.” Initial research suggests that a PCL-5 cut-off score between 31 and 33 is indicative of PTSD. A provisional PTSD diagnosis can be made by treating each item rated as 2 = “Moderately” or higher as a symptom endorsed, then following the DSM-5 diagnostic rule, which requires at least: 1 B item (questions 1–5), 1 C item (questions 6–7), 2 D items (questions 8–14), 2 E items (questions 15–20). The Arabic version of PCL-V has been previously validated in Arabic samples (Ibrahim et al., 2018). Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the scale in the current study was .95.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7 Spitzer et al., 2006). GAD-7 is a 7-item self-report questionnaire that assesses general anxiety. Items are scored on a 4-point scale with (0) indicating “does not exist,” and (3) indicating “nearly every day.” The scores range between 0 and 21, with a cut-off point of 15, indicating severe GAD. The GAD-7 has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 82%. Increasing scores on the scale have been strongly associated with multiple domains of functional impairment (Spitzer et al., 2006). The Arabic version of GAD-7 was previously validated in Arabic samples (Sawaya et al., 2016). Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the scale in the current study was .91.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9 Kroenke et al., 2001) is a 9-item self-report questionnaire that objectifies the degree of depression severity. Items are scored on a 4-point scale with (0) indicating “does not exist,” and (3) indicating “nearly every day.” The scores range between 0 and 27, with a cut-off range of 15–19 indicating moderately severe depression and 20 and above indicating severe depression. The Arabic version of PhQ-9 was previously validated in Arabic samples (Sawaya et al., 2016). Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the instrument in the current study was .88.

COVID-19 Traumatic Stress Scale (Kira, Shuwiekh, Rice, et al., 2020c)

COVID-19 traumatic stress scale is a 12-item scale including three subscales (1) “threat/fear of the present and future infection and death” (5 items), (2)“traumatic economic stress” (4 items), and (3)“isolation and disturbed routines” (3 items). Items are scored on 5 points scale, with (1) indicating not at all and (5) very much. Examples of items include, “How concerned are you that you will be infected with the coronavirus?” “The Coronavirus (COVID-19) has impacted me negatively from a financial point of view.” “Over the past two weeks, I have felt socially isolated as a result of the coronavirus.” In the initial study (Kira, Shuwiekh, Rice, et al., 2020c), the scale showed good construct convergent-divergent and predictive validity. In the current study, the scale had an alpha of .93. Its three Subscales had Cronbach alpha of .91, .83, and .88, respectively.

Statistical Data Analysis

We used Cohen's (1992, p.158) criteria and recommendations to confirm the sample size necessary to detect a medium population effect size at power = .80 for α = .05 for the number of variables in the study. The missing values were less than .05% and replaced by means. The data were analyzed utilizing IBM-SPSS 22. We conducted two hierarchical multiple regression analyses with working memory deficits and inhibition deficits as dependent variables. We entered demographics as independent variables (gender, age, marital status, SES, and education) in the first step, we added resilience in the second step, in the last step, we added WTELS. We recoded the categorical variables into dummy variables. We tested for collinearity between variables and if the variance inflation factor (VIF) is less than 5.00 for all the models (e.g., Hair et al., 2017).

Additionally, to test the model of the direct and mediated effects of WTELS on working memory and inhibition deficits, we conducted a mediated path analysis. The Path model included WTELS as an independent variable, resilience and social support as mediating variables, and working memory and inhibition deficits as outcome variables. We reported direct, indirect, and total effects as standardized regression coefficients. We used a bootstrapping procedure with 10,000 bootstrap samples to examine the significance of direct, indirect (mediated effects), and total effects and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (95% confidence interval, CI) for each variable in the model. To simplify the presentation, we trimmed the model by eliminating the nonsignificant paths. Further, we tested alternative models to explore potentially better fitted or equally fitted models. In alternative models, we reversed the directions of different paths to see which model has the best fit with the data.

While path analysis can analyze several independent and dependent variables simultaneously and identify the total direct and indirect effects, it cannot identify the mediators that contribute to the indirect effects or specifies the effect size of each. For this reason, we supplemented path analysis by SPSS PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013; Model 4) to test the WTELS indirect effects through the mediators and the relative strength of each (effect size and CIs). Further, we used the same procedure to test the direct and indirect effects of WTELS (as an independent variable) and PTSD, depression, anxiety, and COVID-19 traumatic stress as dependent variables, and working memory deficits, inhibition deficits, resilience, social support as mediating variables. We controlled for age, gender, SES, and education as covariates. We utilized bootstrapping sampling (n = 5000) distributions to calculate the direct and indirect effects and CIs (95%) of the estimated effects. The point estimate is considered significant when the CI does not contain zero.

Additionally, We conducted a multi-group invariance analysis to assess whether the path model of the impact of WTELS on executive functions was invariant across genders. We tested four nested structural models sequentially: a configural invariance model, two metric invariance models, and scalar invariance models, and the strict invariance models. In the configural model (i.e., equal form), the parameters were all freely estimated across groups. In the metric model (i.e., weak or partial invariance), the parameters were constrained to be identical across groups. In the scalar model or “strong invariance,” variables and path variances were set to be equal across groups. Lastly, the strict model “strict invariance” additionally constrained the residuals to be the same across groups.

Although there is broad acceptance of the steps for testing measurement and structural invariance, the criteria for evaluating the invariance of models at each level are not as clear. Byrne et al. (1989) have argued that invariance can be established as long as at least two indicators indicate invariance. According to Chen (2007), the null hypothesis of invariance should not be rejected when changes in CFI are less than or equal to 0.01 and in RMSEA are less than or equal to 0.015.

Results

Correlation

WTELS had the highest positive correlation with resilience (.69) and the highest negative correlation with depression (−.52), followed by working memory deficits (−.47). Resilience had the highest negative correlation with working memory deficits (.36) followed by depression (.35). Social support had the highest negative correlation with depression. Working memory deficits had the highest correlation, in addition to inhibition deficit, with depression (.52), anxiety (.46), and PTSD (.43). Inhibition deficits had the highest correlation with PTSD (.52) and depression (.51). COVID-19 had the highest correlation with anxiety (.49), depression (.44), and PTSD (.41). Table 1 presents these results.

Hierarchical Regression Results

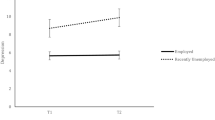

With working memory deficits (WMD) as the dependent variable, gender and SES were predictive of lower WMD in the first step. Adding resilience in the second step, SES lost significance to resilience. Adding resilience increases the variance explained by the model by .102 (R2 = .102). The entered resilience predicted lower WMD with medium effect size (Beta = −.32). In the third step, adding WTELS significantly increased the variance explained by the model (R2 = .084), which equals more than 8% gain, while resilience lost its significance due to their overlap. The entered WTELS predicted lower WMD with a high effect size (Beta = −.41). Table 2 presents these results.

With inhibition deficits (ID) as the dependent variable, in the first step, SES was predictive of lower ID, adding resilience in the second step, the entered resilience increased the variance explained by the model by .017 (R2 = .017). Resilience predicted lower ID with low effect size (Beta = −.13). In the third step, adding WTELS significantly increased the variance explained by the model (R2 = .06), which equals 6% gain, while resilience lost its significance in the model to WTELS. The entered WTELS predicted lower ID with a medium effect size (Beta = −.34). Table 3 presents these results.

Path and PROCESS Analysis Results

The model had a good fit with the data (Chi Square = 2.180, d.f = 4, p = .703, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA = .000). WTELS had a direct large effect size on lower working memory deficits and resilience and indirect effects on lower inhibition deficits in the model. Working memory deficits had direct effects on higher inhibition deficits. Social support had direct effects on lower inhibition deficits. Table 4 includes the direct, indirect, and total effect and 95% confidence interval of the effects of each variable. Figure 1 depicts the direct paths of the variables in the model.

Further, PROCESS analysis indicated that the WTELS direct effects on lower WMD are significant (effect = −.58, SE = .08, t = −-6.90, p = .000, LLCI = -.74, ULCI = -.41), resilience and social support were not significant mediators. For the effects of WTELS on inhibition deficits, the direct effects were not significant. It has indirect effects via its effects on working memory (effect = −.24, SE = .04, t = −5.94, p = .000, LLCI = -.32, ULCI = -.17).

The total effects of WTELS on lower depression were significant and accounted for .347 of the variance in the model (effect = −.55, SE = .07, t = −.7.86, p = .000, LLCI = -.69, ULCI = -.41); Its direct effects were significant (effect = −.40, SE = .08, t = −.4.90, p = .000, LLCI = -.55, ULCI = -.24). Resilience, social support, were not significant mediators of its indirect effects. Lower inhibition deficits were a significant mediator (effect = −.08, SE = .03, t = −.2.77, p = .006, LLCI = -.16, ULCI = -.04), as well as Lower working memory deficits (effect = −.07, SE = .03, t = −.1.90, p = .05, LLCI = -.14, ULCI = -.01).

The total effects of WTELS on lower anxiety were significant and accounted for .234 of the variance in the model (effect = −.39, SE = .06, t = −.6.04, p = .000, LLCI = -.52, ULCI = -.26); Its direct effects were significant (effect = −.28, SE = .08, t = −.3.38, p = .001, LLCI = -.45, ULCI = -.12). Resilience, social support, were not significant mediators of its indirect effects. Lower inhibition deficits were a significant mediator (effect = −.05, SE = .02, t = −.1.93, p = .05, LLCI = -.10, ULCI = -.01), as well as Lower working memory deficits (effect = −.09, SE = .04, t = −.2.08, p = .037, LLCI = -.18, ULCI = -.01).

The total effects of WTELS on lower PTSD were significant and accounted for .246 of the variance in the model (effect = −.76, SE = .21, t = −.3.50, p = .001, LLCI = -1.19, ULCI = -.33); however, the direct effects were not significant. Resilience, social support, and working memory were not significant mediators of its indirect effects. Lower inhibition deficits were the significant mediator of WTELS effects on lower PTSD scores (effect = −.33, SE = .10, t = −.2.30, p = .003, LLCI = -.57, ULCI = -.16).

The total effects of WTELS on lower COVID-19 traumatic stress were significant and accounted for .167of the variance in the model (effect = −.28, SE = .12, t = −.2.22, p = .027, LLCI = -.52, ULCI = -.03); Its direct effects were not significant. Resilience, social support, and lower inhibition deficits were not significant mediators of its indirect effects. Lower working memory deficits were the significant mediator (effect = −.21, SE = .08, t = −.2.43, p = .015, LLCI = -.39, ULCI = -.06).

Alternative Models

We tested four alternative models. In the first alternative model, we reversed the path between working memory and inhibition deficits. The model lost its fit with the data (Chi-Square = 46.780, df = 4, p = .000, CFI = 891, RMSEA = .202). In the second alternative model, we reversed only the direction between WTELS and working memory. The model fit equally with our chosen model. That may mean that higher working memory is associated with WTELS as well. In the third alternative model, we reversed all the paths. The model fit with data was poor (Chi-Square = 36.825, df = 4, p = .000, CFI = .917, RMSEA = .177) and much lower than the chosen model. In alternative model 4, we reversed only the paths from working memory deficits and inhibition deficits. The model fitted with data (Chi-Square = 8.107, df = 4, p = .088, CFI = .990, RMSEA = .063); however, its fit was much lower than the chosen model. Alternative model figures can be viewed in the supplemental materials.

Multigroup Invariance across Binary Genders (Male/Female)

Multigroup structural invariance for the path model for the effects of WTELS on executive functions indicated that the model is strictly invariant between genders (males and females). Table 5 includes the structural fit indexes on the four levels (configural, metric, scalar, and strict), which did not significantly differ from each other according to the criteria previously discussed.

Conclusions and Discussion

Results confirmed the study hypotheses and the validity of WTELS as a master motivator that is strongly associated with the activation, mobilization, maximization, and optimization of executive functioning and lowered working memory and inhibition deficits. The pattern of these relationships was strictly invariant between males and females. While the WTELS pathway impact on executive function explored in the study is direct, there are potentially other indirect pathways of its impact to be explored in future studies.

While the model we tested was found superior to alternative models, It had an equal model fit to one of the alternative models in which we reversed the path between WTELS and working memory, which may mean that a two-way path between them is present and higher working memory can be associated with higher WTELS, and vice versa. Also, reversing the path between working memory and inhibition resulted in a loss of the model fit, which means that working memory is more likely to affect inhibition than vice versa, contrary to many models that suggested the opposite (e.g., Piotrowski et al., 2019). Additionally, when we reversed all the paths in an alternative model to make executive functions, resilience, and social support the predictors of WTELS, the alternative model did not fit the data. The interface between working memory and inhibition, in their relationship with WTELS, needs to be explored further in future research.

WTELS was found to be highly predictive of PTG (Kira, Özcan, Shuwiekh, et al., 2020a). PTG was found to be associated with lower executive function deficits (Eren-Koçak & Kiliç, 2014), which may mean that PTG may mediate the effects of WTELS on EF, in addition to its direct effects. The potential mediation of PTG needs to be explored in future studies. There is a need to map the architecture of the motivation field. The motivation field starts with WTELS as its core meta motivator, which extends to personal and group identities’ goals and life projects and activates cognitive processing. The activation of cognitive processing helps persons pursue these goals, cope with life stressors, and learn and grow after exposure to traumas. However, persistent acute stressors and psychopathology can negatively affect the person’s WTELS increasing suicide cognitions and behaviors, which may negatively affect executive functions, reversing the process dynamics.

What exactly are the motivational factors of WTELS that fuel executive function? Via what mechanisms do WTELS trigger control to engage, withdraw, or shift focus or expand and maximize working memory and inhibition control? What role might WTELS play in driving the temporal dynamics of control that may vary in focus and intensity over time? The impact of motivation on control function has been shown to vary in systematic ways across individuals (see Fröber & Dreisbach, 2014; Jimura et al., 2010; Leotti & Wager, 2010; Locke & Braver, 2008; Padmala & Pessoa, 2011; Pessoa, 2009; Savine et al., 2010; Westbrook et al., 2013). The impact of motivation on working memory has been shown to vary across motivation states (Gilbert & Fiez, 2004; Heitz et al., 2008; Jimura et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2004). Such findings indicate that the relationship between motivation, working memory capacity, and control inhibition are robust and identifies the biological and neuropsychological mechanisms behind this interface. Further, a previous study found that WTELS predicted a significant decrease in psychopathology and a significant increase in self-esteem and emotion regulation, and these dynamics were strictly invariant across gender, regional, age, and religious groups (Kira, Shuwiekh, Kucharska, et al., 2020b). The current study added that while WTELS is directly associated with lower depression, anxiety, PTSD, and the novel COVID-19 traumatic stress syndrome, its positive effects on executive functions mediate its indirect effects. Recent studies found that COVID-19 traumatic stress is associated with increased executive function deficits (Kira, Alpay, Ayna, et al., 2021a; Kira, Alpay, Turkeli, et al., 2021b).

The advances in neurosciences allow us to identify the neurological underpinning of the mechanism and pathways of the relationships between will (volition) to exist, live and survive, motivation, and executive functions. Neuroscientific studies of agency and willed action linked agency to widely distributed brain areas encompassing frontal motor and parietal monitoring sites. Impairment of volitional control is known to be associated with neuropathology (Haggard & Libet, 2001) and reduction in the volume of prefrontal cortical grey matter (e.g., Raine et al., 2001). Motivation to willful act would be created and maintained in the human brain by value-processing dynamics that process an ever-evolving system of valuations of goals and objectives (e.g., Kira, 1987; Wasserman & Wasserman, 2020). These value processors are specializations of different prefrontal cortical areas (Arnsten et al., 2012). Working memory consists of processes that are operative in the prefrontal cortex(PFC). The role of the prefrontal cortex is not to store information but rather to actively focus attention on the relevant sensory representation, select information, and perform executive functions that are necessary to control the cognitive processing of the information. In contrast, posterior sensory areas are responsible for keeping the information in working memory (Lara & Wallis, 2015). The inhibition processes are instead located in lateral-inferior frontal and medial frontal cortical areas and the caudate nucleus (Boehler et al., 2010).

The current study highlighted the need for innovation to develop WTELS-focused intervention and prevention programs that may include motivational interviewing, focusing on nurturing and optimizing WTELS in different age groups. Enhancing and optimizing EF by optimizing WTELS may be an essential intervention and prevention transdiagnostic strategy. Such a strategy can target school and college students and clinical and non-clinical populations to optimize WTELS and EF and enhance mental health.

Additionally, the unique sensory processing patterns of depressed, suicidal individuals(i.e., sensory sensitivity, sensation avoiding, and low registration) whose WTELS was compromised have been reported as crucial factors in determining adverse mental health outcomes (Serafini, Gonda, et al., 2017b). Depressed suicidal individuals probably have WTELS motivation deficits. Interventions that target optimizing WTELS may help positively alter their sensory processing patterns and alleviate depression and prevent non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior.

The current study has several limitations. One of the limitations is that the study was conducted in convenient samples with limited and biased representation. Also, the measures used are based on participants’ self-reports, which are subject to under-or over-reporting due to social desirability. Additionally, self-report EF may not index the same constructs as performance-based EF tests. Future studies may be conducted using performance-based EF tests.

Also, the study utilized a cross-sectional design. Additionally, when we talk about direct and indirect effects, we have to caution that we talk about statistical probabilistic stochastic terms used in PROCESS and path analyses that do not mean the same thing in deterministic sciences of cause and effect. We emphasize that PROCESS and path analyses do not demonstrate causality. Regardless of these limitations, the study provided empirical evidence of the impact of WTELS as a master motivator on enhancing executive functions.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aarts, E., Roelofs, A., Franke, B., Rijpkema, M., Fernandez, G., et al. (2010). Striatal dopamine mediates the interface between motivational and cognitive control in humans: Evidence from genetic imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology, 35, 1943–1951.

Arnsten, A. F., Wang, M. J., & Paspalas, C. D. (2012). Neuromodulation of thought: Flexibilities and vulnerabilities in prefrontal cortical network synapses. Neuron, 76(1), 223–239.

Baumeister, R. F. (2016). Toward a general theory of motivation: Problems, challenges, opportunities, and the big picture. Motivation and Emotion, 40(1), 1–10.

Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28, 489–498.

Boehler, C. N., Appelbaum, L. G., Krebs, R. M., Hopf, J. M., & Woldorff, M. G. (2010). Pinning down response inhibition in the brain—Conjunction analyses of the stop-signal task. Neuroimage, 52(4), 1621–1632.

Bornet, M. A., Bernard, M., Jaques, C., Truchard, E. R., Borasio, G. D., & Jox, R. J. (2020). Assessing the will to live: a scoping review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 61 (4), 845–857.e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.09.012

Botvinick, M., & Braver, T. (2015). Motivation and cognitive control: From behavior to neural mechanism. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 83–113.

Braem, S., Duthoo, W., & Notebaert, W. (2013). Punishment sensitivity predicts the impact of punishment on cognitive control. PLoS One, 8, e74106.

Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J., & Muthén, B. (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456

Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor–davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019–1028.

Carmel, S. (2001). The will to live: Gender differences among elderly persons. Social Science & Medicine, 52(6), 949–958.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 14(3), 464–504.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Cohen-Zimerman, S., & Hassin, R. R. (2018). Implicit motivation improves executive functions of older adults. Consciousness and Cognition, 63, 267–279.

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82.

Corno, L., & Kanfer, R. (1993). Chapter 7: The role of volition in learning and performance. Review of Research in Education, 19(1), 301–341.

Engelmann, J. B., Damaraju, E., Padmala, S., & Pessoa, L. (2009). Combined effects of attention and motivation on visual task performance: Transient and sustained motivational effects. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 3, 4.

Eren-Koçak, E., & Kiliç, C. (2014). Posttraumatic growth after earthquake trauma is predicted by executive functions: A pilot study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(12), 859–863.

Fröber, K., & Dreisbach, G. (2014). The differential influences of positive affect, random reward, and performance-contingent reward on cognitive control. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 14, 530–547.

Gilbert, A. M., & Fiez, J. A. (2004). Integrating reward and cognition in the frontal cortex. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 4, 540–552.

Haggard, P. (2017). Sense of agency in the human brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 18(4), 196–207.

Haggard, P., & Libet, B. (2001). Conscious intention and brain activity. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8(11), 47–64.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(5), 616–632.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Heitz, R. P., Schrock, J. C., Payne, T. W., & Engle, R. W. (2008). Effects of incentive on working memory capacity: Behavioral and pupillometric data. Psychophysiology, 45, 119–129.

Holst, Y., & Thorell, L. B. (2018). Adult executive functioning inventory (ADEXI): Validity, reliability, and relations to ADHD. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 27(1), e1567.

Hutschnecker, A. A. (1951). The will to live. Cornerstone Library.

Ibrahim, H., Ertl, V., Catani, C., Ismail, A. A., & Neuner, F. (2018). The validity of posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) as screening instrument with Kurdish and Arab displaced populations living in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 259.

Jimura, K., Locke, H. S., & Braver, T. S. (2010). Prefrontal cortex mediation of cognitive enhancement in rewarding motivational contexts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107, 8871–8876.

Khoo, S. S., & Yang, H. (2020). Social media use improves executive functions in middle-aged and older adults: A structural equation modeling analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 11, 106388.

Kira, I. (1987). Human values: A conceptual model for the dynamics of value processing. Thesis presented to the graduate faculty of California State University, Hayward (East Bay). https://www.academia.edu/22943131/Human_values_a_conceptual_model_for_the_dynamics_of_value_processing_. Accessed on 6//10/202.

Kira, I., Alawneh, A., Boumediene, S., Lewandowski, L., & Laddis, A. (2014a). Dynamics of oppression and coping from traumatology perspective: The example of Palestinian youth. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 20(4), 385–411.

Kira, I., Lewandowski, L., Chiodo, L., & Ibrahim, A. (2014b). Advances in systemic trauma theory: Traumatogenic dynamics and consequences of backlash as a multi-systemic trauma on Iraqi refugee Muslim adolescents. Psychology, 5, 389–412.

Kira, I. A, Özcan, N. A., Shuwiekh, H, Kucharska, J., Al-Huwailah, A. & Kanaan, A. (2020a). The compelling dynamics of “will to exist, live and survive” on effecting PTG upon exposure to adversities: Is it mediated, in part, by emotional regulation, resilience, and spirituality. Traumatology: An International Journal. Online first.

Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H., Kucharska, J., Al-Huwailah, A. H., & Moustafa, A. (2020b). “Will to exist, live and survive” (WTELS): Measuring its role as master/meta-motivator and in resisting oppression and related adversities. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 26(1), 47–61.

Kira, I.; Shuwiekh, H.; Rice, K.; Ashby, J; Elwakeel, S.; Sous, M.; Alhuwailah, A; Baali, S.; Azdaou, C.; Oliemat, E.& Jamil, H. (2020c). Measuring COVID-19 as traumatic stress: Initial psychometrics and validation. Journal of Loss and Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1790160, 26, 220, 237.

Kira, I., Alpay, E.H., Ayna, Y.E. et al. (2021a). The effects of COVID-19 continuous traumatic stressors on mental health and cognitive functioning: A case example from Turkey. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01743-2

Kira, I., Alpay, E. H., Turkeli, A., Shuwiekh, H., Ashby, J. S. & Alhuwailah, A. (2021b). he effects of COVID-19 traumatic stress on executive functions: The case of Syrian refugees in Turkey. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1869444

Kira, I., Özcan, N., Shuwiekh, H., Kucharska, J., Al-Huwailah, A., & Bujold-Bugeaud, M. (2021c). Mental health dynamics of interfaith spirituality in believers and non-believers: The two circuit pathways model of coping with adversities: Interfaith Spirituality and Will-to Exist, Live and Survive. Psychology, 12, 992–1024.

Kira, I., Shuwiekh, H., Rice, K., Ashby, J.S., Alhuwailah, A., Sous, M., Baali, S., Azdaou, C., Oliemat, E., & Jamil, H. (In press). Coping with COVID-19 continuous complex stressors: The “Will-to-Exist-Live, and Survive” and perfectionistic striving. Traumatology: An International Journal

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

Lara, A. H., & Wallis, J. D. (2015). The role of prefrontal cortex in working memory: A mini-review. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 9, 173.

Leotti, L. A., & Wager, T. D. (2010). Motivational influences on response inhibition measures. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36, 430–434.

Libby, R., & Lipe, M. G. (1992). Incentives, effort, and the cognitive processes involved in accounting-related judgments. Journal of Accounting Research, 30(2), 249–273.

Locke, H. S., & Braver, T. S. (2008). Motivational influences on cognitive control: Behavior, brain activation, and individual differences. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 99–112.

Mischel, W., & Ayduk, O. (2011). Willpower in a cognitive affect processing system: The dynamics of delay of gratification. In K. D. Vohs & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 83–105). Guilford Press.

Padmala, S., & Pessoa, L. (2011). Reward reduces conflict by enhancing attentional control and biasing visual cortical processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23, 3419–3432.

Pessoa, L. (2009). How do emotion and motivation direct executive control? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(4), 160–166.

Pessoa, L., & Engelmann, J. B. (2010). Embedding reward signals into perception and cognition. Frontiers in neuroscience, 4, 17.https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2010.00017

Piotrowski, K. T., Orzechowski, J., & Stettner, Z. (2019). The nature of inhibition in a working memory search task. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 31(3), 285–302.

Raine, A., Lencz, T., Bihrle, S., et al. (2001). Reduced prefrontal gray matter volume and reduced autonomic activity in antisocial personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 119–127.

Savine, A. C., Beck, S. M., Edwards, B. G., Chiew, K. S., & Braver, T. S. (2010). Enhancement of cognitive control by approach and avoidance motivational states. Cognition & Emotion, 24, 338–356.

Sawaya, H., Atoui, M., Hamadeh, A., Zeinoun, P., & Nahas, Z. (2016). Adaptation and initial validation of the patient health questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and the generalized anxiety disorder–7 questionnaire (GAD-7) in an Arabic-speaking Lebanese psychiatric outpatient sample. Psychiatry Research, 239, 245–252.

Scali, J., Gandubert, C., Ritchie, K., Soulier, M., Ancelin, M. L., & Chaudieu, I. (2012). Measuring resilience in adult women using the 10-items Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Role of trauma exposure and anxiety disorders. PloS one, 7(6), e39879.

Schlüter, C., Fraenz, C., Pinnow, M., Voelkle, M. C., Güntürkün, O., & Genç, E. (2018). Volition and academic achievement: Interindividual differences in action control mediate the effects of conscientiousness and sex on secondary school grading. Motivation Science, 4, 262–273.

Serafini, G., Canepa, G., Adavastro, G., Nebbia, J., Belvederi Murri, M., Erbuto, D., Pocai, B., Fiorillo, A., Pompili, M., Flouri, E., & Amore, M. (2017a). The relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 149.

Serafini, G., Gonda, X., Canepa, G., Pompili, M., Rihmer, Z., Amore, M., & Engel-Yeger, B. (2017b). Extreme sensory processing patterns show a complex association with depression, and impulsivity, alexithymia, and hopelessness. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 249–257.

Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine, 32(6), 705–714.

Sims, R. C., Levy, S. A., Mwendwa, D. T., Callender, C. O., & Campbell Jr., A. L. (2011). The influence of functional social support on executive functioning in middle-aged African Americans. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 18(4), 414–431.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W., & Lowe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1092–1097.

Stolorow, R. D., & Atwood, G. E. (2014). Contexts of being: The intersubjective foundations of psychological life. Routledge.

Taylor, S. F., Welsh, R. C., Wager, T. D., Phan, K. L., Fitzgerald, K. D., & Gehring, W. J. (2004). A functional neuroimaging study of motivation and executive function. NeuroImage, 21, 1045–1054.

Wasserman, T., & Wasserman, L. (2020). Motivation, effort, and the neural network model. Springer International Publishing AG.

Westbrook, A., Kester, D., & Braver, T. S. (2013). What is the subjective cost of cognitive effort? Load, trait, and aging effects revealed by economic preference. PLoS One, 8, e68210.

Wu, L., Zhang, X., Wang, J., Sun, J., Mao, F., Han, J., & Cao, F. (2021). The associations of executive functions with resilience in early adulthood: A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 282, 1048-1054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.031

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 230 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kira, I.A., Ayna, Y.E., Shuwiekh, H.A.M. et al. The association of WTELS as a master motivator with higher executive functioning and better mental health. Curr Psychol 42, 7309–7320 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02078-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02078-8