Abstract

Individuals with psychopathic traits have been identified to display insecure attachment. However, it is not clear which attachment dimension contributes more to high psychopathic traits, and more specifically to callous-unemotional (CU) traits, which parental relationship is more influential and if this differs across gender. This study examined the associations of adult attachment dimensions (avoidance and anxiety) and parental factors (regard, responsibility and control) with CU traits (N = 1149) using Hierarchical Linear Regression. The relationship with both parents was assessed separately to identify their unique contribution to CU traits in males and females respectively. The avoidant attachment positively predicted while the anxiety attachment dimension negatively predicted CU traits and this was the case for both male and female participants. Interestingly, maternal regard was a negative predictor of CU traits in males only, whereas paternal responsibility arose as a positive predictor of CU traits in females only. Attachment dimensions explained the largest variance in both males and females. Findings point to the importance of attachment dimensions contributing to CU traits even in an adult sample. Parental variables were less influential on CU traits compared to attachment related variables and findings suggest that there are differences between males and females. These findings have important implications for gender differentiated attachment based interventions for individuals with CU traits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Psychopathy is characterised by a cluster of affective and interpersonal personality features such as superficial charm, egocentricity, callousness, dishonesty, lack of empathy as well as impulsive and deviant behaviours, including aggression, irresponsibility and in some cases antisocial behaviour and criminal offending (Hare, 1996). Callous-unemotional (CU) traits form the primary characteristics of psychopathy and signify a number of affective personality traits linked to lack of guilt and empathy, shallow emotions and insensitivity towards others (Fanti et al., 2017; Frick, 2004). Research indicates that CU traits develop in early childhood and they are considered to be the developmental precursor of psychopathic traits in adults (Kyranides et al., 2016; Waller et al., 2019). Given their negative developmental trajectory, children with these traits are at risk of developing more severe antisocial behaviour and emotional deficits (Fanti et al., 2017; Frick & White, 2008) and have been associated with considerable societal burden (Asscher et al., 2011). These traits have attracted much interest and as a result a specifier of limited prosocial emotions has been added to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) for diagnosing conduct disorder (Fanti et al., 2018; Kimonis et al., 2015). Research has embraced the possible association between developmental factors such as attachment and psychopathic traits (Van Der Zouwen et al., 2018) with some studies showing a positive association between insecure attachment and the development of psychopathic traits in both adult and child populations (Alzeer et al., 2019; Kohlhoff et al., 2020). Despite this, there have been mixed findings in relation to the impact of gender differences on attachment contributing to CU traits and the influence of attachment figures. Therefore, this study examines the relationship between attachment, parental factors and CU traits in males and females as adults, to better understand the influence and their clinical importance and help inform CU traits prevention and/or management efforts.

Attachment and Psychopathic Traits

Bowlby (1973, 1980) put forward a theory about attachment by interpreting it as a biological mechanism that allows humans to develop emotional connections with significant others. Ainsworth (1989) expanded the theory; categorising warm and trustworthy bonds as secure attachment and alternatively those that lack the aforementioned, as avoidant and anxious attachments. More specifically, Brennan et al. (1998) suggested that individuals who score high on avoidance attachment dimension tend to rely more on themselves and do not view others as dependable in their relationships, especially with regard to satisfying and maintaining their needs, and are characterised by a reduced expression of affection and intimacy (Fraley & Shaver, 1997; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). On the other hand, individuals who score high on the anxiety attachment dimension have a negative view of self, they are characterised by insecurity concerning the responses of others, with a high fear of rejection, while overly seeking closeness in their relationships (Fraley & Shaver, 1997; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

The relationship between a child and a parent has been connected with emotional, social and behavioural development (e.g., Van Der Voort et al., 2014). While secure attachment is associated with the development of trust, stability and control that enables one to form healthy relationships in life (Ainsworth & Witting, 1969; Simmons et al., 2009), insecure attachment has been associated with development of unhealthy traits and behaviours such as psychopathic traits (Alzeer et al., 2019; Van Der Zouwen et al., 2018). Several retrospective studies indicate that participants scoring high on psychopathic traits and anxiety attachment dimension, recall problematic childhood environments; involving lack of affection and warmth, parental neglect or separation and severe punishment strategies used by caregivers (Frodi et al., 2001; Waller et al., 2019). Literature also supports that psychopathic traits, especially the affective dimension, is associated with avoidance attachment in both males and females (Walsh et al., 2019). However, it is still unclear whether anxiety or avoidance attachment has the greatest association with CU traits. There has been a focus on studies using incarcerated populations, through the study of psychopathic scores (Bisby et al., 2017; Frodi et al., 2001) and an increase in studies conducted with non-clinical populations (e.g., Blanchard & Lyons, 2016; Mack et al., 2011), yet the results are far from conclusive. While there is support for both avoidance and anxiety attachment being associated with higher psychopathy scores in a non-clinical population (Mack et al., 2011), Van Der Zouwen et al. (2018) found no significant results in community samples compared to clinical samples. Given these mixed findings, this study aims to look more into community samples and examine the significance of this association.

Gender Differences, Attachment and Psychopathic Traits

Research shows that the prevalence of CU traits is significantly higher in men compared to women (Ciucci et al., 2014; Fanti et al., 2018). Attachment also presents differently in males and females with research suggesting that males exhibit higher levels of avoidant attachment while females display higher levels of anxiety attachment (Blanchard & Lyons, 2016; Schmitt & Jonason, 2015). Recently Blanchard and Lyons (2016) illustrated a link between avoidant attachment in males and controlling mothers, and between both anxiety and avoidant attachment in females and low-caring fathers. When it comes to the gender of parents, some findings convey that a rejecting father might be more influential, even when maternal warmth is present (Frodi et al., 2001) while low maternal warmth has been also associated with the development of CU traits (Bisby et al., 2017; Kimonis et al., 2013). Moreover, the literature shows that parental care in same-sex dyads (mother-daughter or father-son relationships) predicted affective empathy (Lyons et al., 2017), and higher quality in these relationships was a protective factor against the decline of mental health (Steele & Mckinney, 2019). According to a recent systematic review (Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2019), there have been several, behavioural differences observed within the same-sex dyads, which contributed to the development of externalising behaviours (e.g., aggressiveness, delinquency). More specifically it was reported that boys were rebelling more against maternal control than paternal control and girls with aggressive behaviour had less communication with their fathers and were more influenced by maternal control (Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2019). The literature does not extensively cover parental dyads, especially in relation to CU traits, as it has primarily focused on the mother-child relationship (Bisby et al., 2017; Kimonis et al., 2013) and their impact on developing psychopathic traits. Thus, comparing all general dyads (mother-son/daughter or father-son/daughter) is necessary to comprehend the extent to which gender impacts the developmental trajectory of psychopathic traits.

The Current Study

A more in-depth view is needed to further enhance the understanding of anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions and how they contribute to the development of psychopathic traits and more specifically CU traits. This is particularly important given their longitudinal association with conduct and emotional symptoms (Fanti et al., 2017; Kyranides et al., 2016), along with their recent connection to relationship violence in adulthood (Golmaryami et al., 2021). The reported findings from the literature are far from conclusive and investigations beyond clinical samples is vital. Insight into precursors of psychopathic traits could allow further understanding in the constellation of these personality traits. This in turn could help identify factors that could contribute to interventions, which may alleviate difficulties that individuals with these traits face and the potential harm they pose to those around them (Asscher et al., 2011). Despite the fact that there are several studies examining gender differences, there are to our knowledge few to none that investigate CU traits more in-depth by considering the gender of parents as well as parental factors and attachment dimensions.

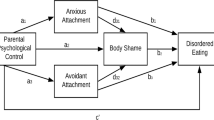

The aim of this study is to explore how anxious and avoidant attachment dimensions, maternal and paternal factors predict CU traits in women and men separately. Considering the strong support from the literature it is hypothesised that: 1) CU traits will manifest differently across genders with males reporting higher levels of CU traits compared to females (Ciucci et al., 2014; Fanti et al., 2018). 2) Avoidance and anxiety attachment dimensions are expected to be significantly associated with CU traits, however due to mixed findings (Blanchard & Lyons, 2016; Mack et al., 2011; Walsh et al., 2019), we do not hypothesise the direction of these associations or their relationships with genders. 3) Among parental factors, there is strong support that mothers are more influential figures so it is expected that maternal factors will contribute more than paternal factors in relation to CU traits in both genders (Bisby et al., 2017; Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994).

Methods

Participants

The research study was prospectively reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Edinburgh. The sample consisted of 1170 adults ranging in age from 18 to 72 years (M = 30.96, SD = 11.66). One of the main aims of the study was to explore gender differences and the study variable CU traits, which led to the exclusion of 21 participants who did not identify with either gender. The final sample yielded 1149 participants 752 identified as females (65%) and 397 identified as males (35%). Of the final sample 16.1% of participants had completed a high school diploma, 7.3% had an associate’s degree or equivalent, 43.9% had a Bachelors, 29.5% had obtained a Master’s degree and 3.1% had completed a Doctorate. With regard to employment, 6.3% of participants were unemployed, 38.1% were students, 13% were working part-time, 40.7% were working full-time while 1.9% were retired.

Measures

Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits

The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional traits (ICU; Frick, 2004) is a 24-item self-report scale designed to assess callous, unemotional and carelessness traits (Frick, 2004). The ICU has been derived from the callous-unemotional scale of the Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD) and captures the affective component of psychopathy (Ray & Frick, 2020). Each item is scored on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 3 (definitely true). Scores are calculated by reverse scoring the positively worded items and then summing them together to get a total score (Frick, 2004). The inventory has been used widely (Ray & Frick, 2020), with community samples (Kyranides et al., 2016), and samples of juvenile offenders (Kimonis et al., 2013). In the current study the total ICU showed good internal consistency (α = .80) similar to scores reported in other studies (e.g., Kyranides et al., 2017; Ray & Frick, 2020).

Relationship Scales Questionnaire

The Relationship Scales Questionnaire (RSQ; Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994) is a self-report measure with 30 items assessing a) avoidance (α = .78; e.g., “I find it difficult to trust others”); and b) anxiety (α = .81; e.g., “I worry about being abandoned”) in close relationships (Kurdek, 2002). The items of the questionnaire include questions that explore close relationships with friends and family, as well as romantic relationships. The answer to each item is scored based on Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The RSQ has been assessed for its validity, efficiency and reliability and has been used to assess adult attachment (Alzeer et al., 2019; Blanchard & Lyons, 2016; Henschel et al., 2020).

Parent Adult-Child Relationship Questionnaire

The Parent Adult-Child Relationship Questionnaire (PACQ; Peisah et al., 1999) is a self-report measure comprising of 26 items examining relationships with the mother and the father reflecting the following dimensions: (1) Regard (filial gratitude or reciprocity and perceived closeness); (2) Responsibility (feeling responsible for the parent) and (3) Control (parental power). Participants are asked to indicate the extent to which each statement describes their relationship with their mother and father using a 4-point scale from 0 (not true at all) to 3 (very true). Half of the items access the relationship with the mother and the PACQ includes two factors: regard (α = .77 in the current study; e.g., ‘I respect my mother’s opinion’) and responsibility (α = .78; e.g. ‘I feel responsible for my mother’s happiness’). The other half of the items access the relationship with the father and include three factors: regard (α = .82; ‘I respect my father’s opinion’), responsibility (α = .63; e.g., ‘Something will happen to my father if I don’t take care of him’) and control (α = .76; e.g., ‘My father tries to dominate me’). Previous research has reported similar internal reliability for the PACQ (e.g., Alzeer et al., 2019; Peisah et al., 1999).

Procedure

The battery of questionnaires was processed via a secure online platform. The link to the survey was administered through various social media networks and sites, which provided the participants with a free and easier access to the questionnaires from their private devices (smartphones, computers, iPads). All individuals had to read the information about the study and provided informed consent. Participants provided some demographic information (age, gender), followed by the three questionnaires accessing callous unemotional traits, attachment and parental relationships, which were administered in the same order for all participants. The survey took about 15–20 min to complete and participation was voluntary. At the end of the study, participants were debriefed and thanked for their time.

Plan of Analysis

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 25. Preliminary analyses included checking for missing data, outliers and normality of distribution. Demographic characteristics of participants were explored followed by independent t-tests to examine gender differences on CU traits, attachment dimensions, maternal and paternal relationships. Correlation analysis was used to explore the associations of mother-son, mother-daughter, father-son and father-daughter relationships with CU traits. Hierarchical multiple regressions were then run separately for male and female participants entering variables in the same order. Age was entered first (step 1), while attachment variables (avoidance and anxiety) were entered second (step 2) followed by parental factors (regard, responsibility and control) which were entered separately for mother (step 3) and father (step 4) with CU traits as the outcome variable. The overlap in variance between predictors and the unique variance by each predictor was assessed.

Results

With regard to gender differences, there were significant differences in CU traits t(1147) = 9.32, p < .001, with males reporting higher levels than females (Table 1). Additionally significant differences were found in the levels of anxiety related to attachment reported t(1147) = 3.58, p < .005 with females reporting higher levels than men. Both mother t(1139) = 2.07, p < .05 and father t(1123) = 2.90, p < .01 responsibility and father regard t(1123) = 1.97, p < .05 variables, were significantly higher in men compared to women in all cases. Due to the significant differences in CU traits found in men and women further analysis were conducted separately.

Although correlations were generally similar in pattern across gender there were some differences in these associations. For both males and females (see Table 2), CU traits were significantly positively correlated with avoidance and anxiety. For males (Table 2 below the diagonal) CU traits were negatively correlated with age and both mother and father regard but were positively correlated to paternal control. For females (Table 2 above the diagonal) age and the parental variables were not significantly correlated with CU traits.

In order to examine which variable/s have the largest impact on CU traits, hierarchical regression analysis were conducted to assess the unique contribution of the predictors, separately for males and females. Tests to determine linearity, homoscedasticity and multicollinearity were performed and no violation of the assumptions (r < 0.7, tolerance >0.1; VIF < 10) was revealed. Age was entered in step 1 and accounted for a significant 2% of variance in CU traits for men, F(1, 384) = 6.43, p < .05 (Table 3) and 0.3% of variance of CU traits in women but the model for women was not significant (p > .05) (Table 4). Attachment dimensions (avoidance and anxiety) were entered is step 2 with the models accounting for 18% of variance in CU for males F(3, 384) = 28.67, p < .001 and 18% for women F(3,720) = 51.66, p < .001. From this overall variance, attachment dimensions explained 16% for men and 18% for women and this additional variance was significant for both men F Change(2, 381) = 39.15, p < .001 and women F Change(2, 717) = 76.16, p < .001. In step 3, the mother related variables were entered (regard and responsibility) and the models explained 21% of the variance in CU traits in men F(5, 384) = 19.63, p < .001 but remained at 18% in women. From this variance, the mother variables accounted for 3% of the variance of CU traits in male participants which was significant, F Change(2, 379) = 5.14, p < .01, but the same addition of mother related variables contributed to no additional variance explained in female participants (p > .05). Finally, the addition of the father variables (regard, responsibility and control) in step 4 explained 22% of the variance of CU traits in men F (8, 384) = 12.63, p < .001 and reached 19% in women, F (8, 720) = 20.01, p < .001. From this variance, the addition of the father variables accounted for 1% of the variance of CU traits for both men and women but this addition was not significant for either men or women (ps > .05). Following from the above, attachment explained the largest variance of CU traits in both men and women. The results of the hierarchical regression analysis were conducted and presented separately for men (Table 3) and women (Table 4).

In the final models, CU traits in men (Table 3) were significantly positively predicted by attachment avoidance (β = .40, p < .001) and negatively predicted by age (β = −.11, p < .01), attachment anxiety (β = −.11, p < .05) and mother regard (β = −.15, p < .01). For women (Table 4) CU traits were significantly positively predicted by attachment avoidance (β = .45, p < .001) and negatively predicted by age (β = −.08, p < .05) and attachment anxiety (β = −.12, p < .001). Interestingly in the final model the variable assessing feelings of responsibility for the father was also a positive predictor (β = .09, p < .05) for CU traits in women, but none of the mother variables arose as significant predictors (ps > .05).

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine the previously unexplored predictive associations of attachment dimensions (avoidance and anxiety) and parental factors of regard, responsibility and control with CU traits separately in males and females. Our findings indicated age and attachment anxiety as significant negative predictors of CU traits in both males and females, while attachment avoidance appeared as a significant positive predictor of CU traits in both genders. Surprisingly, among the parental factors, high regard for mothers negatively predicted CU traits only in males (Lyons et al., 2017), while the factor assessing responsibility towards the father positively predicted CU traits only in females. Overall, CU traits manifested differently across genders with males showing significantly higher levels of CU traits than females (Fanti et al., 2018), possibly due to stronger genetic influence associated with the presentation of these traits (Fontaine et al., 2010).

Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study contributes to the attachment and psychopathy literature by showing that age was an influential predictor for CU traits in both males and females indicating that these traits may decrease with age (Fanti et al., 2017). Considering that the current study focused on the affective dimension (CU traits), our findings are in alignment with previous research (Asscher et al., 2011), suggesting that it is important to target these traits in early years when attachment and CU traits are more malleable (Fraley & Roisman, 2019; Kohlhoff et al., 2020). Intervening early is important as individuals with high and stable conduct disorder symptoms and callous–unemotional traits are consistently at higher risk for individual, behavioral and contextual problems in adolescence (Eisenbarth et al., 2016; Fanti et al., 2018) as well as relationship issues in adulthood, reporting more incidences of dominance, violence and lower relationship satisfaction (Golmaryami et al., 2021).

Attachment dimensions explained the largest variance in CU traits in both genders, demonstrating that attachment is a determining factor even in adulthood (Alzeer et al., 2019; Blanchard & Lyons, 2016). More specifically, attachment avoidance appeared to have predictive power for CU traits in both genders. This finding is in-line with previous research (e.g., Blanchard & Lyons, 2016; Walsh et al., 2019) and is supported by the attachment framework (Brennan et al., 1998) considering that attachment avoidance involves fear of depending on others within interpersonal relationships, with an excessive need for self-reliance. Thus, individuals with high levels of avoidance attachment, tend to evade intimate and close relationships, use deactivating strategies that minimize the experience of rejection to protect against threats of self-image (Fraley & Shaver, 1997; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007), which limits their access and awareness of recognizing emotions in others making it difficult for them to empathize, key characteristics of CU traits (i.e., Henschel et al., 2020; Mack et al., 2011; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007; Simpson et al., 2011; Van Der Zouwen et al., 2018). Taking the aforementioned findings into account, in combination with an established link between empathetic and moral disturbances with the affective-interpersonal features of psychopathy in both genders (Seara-Cardoso et al., 2012), it seems that attachment avoidance should be prioritized when designing interventions for individuals with CU traits within clinical settings (Daly & Mallinckrodt, 2009) in managing CU traits but also in mainstream settings (schools, parenting programs) focusing on prevention (Kyranides et al., 2018; Rose et al., 2019).

Furthermore, we found attachment anxiety to negatively predict CU traits in both males and females, acting as a protective factor. One possible explanation for this finding could be that attachment anxiety involves a fear of rejection or abandonment within interpersonal relationships, which is accompanied with an excessive need for approval from others (Brennan et al., 1998; Fraley & Shaver, 1997). Therefore, individuals with high attachment anxiety are more likely to care/want and seek close intimate relationships and have been found to be more empathetically accurate (Simpson et al., 2011) so they are less likely to exhibit high CU traits. Furthermore studies have demonstrated that individuals with psychopathic traits are characterized as fearless (Kyranides et al., 2016; Waller et al., 2019), reporting low levels of anxiety and arousal. Together, these findings suggest that different attachment dimensions may independently impact CU characteristics in adults (Van der Zouwen et al., 2018), specifically highlighting that individuals with high attachment avoidance and low attachment anxiety are at higher risk to develop CU traits. Therefore it is necessary for practitioners to identify these high-risk individuals early, to reduce the possibility of them developing these dysfunctional attachments and personality traits. The findings of the present study have specific implications for clinical interventions targeting the development of CU traits, suggesting that the therapeutic goals should be focused on restoring attachment security through the identification of specific attachment dimensions (Daly & Mallinckrodt, 2009; Wright & Edginton, 2016) reducing avoidant patterns and increasing secure attachment behaviors.

For parental factors, our hypothesis was partially supported as only mother regard appeared to be a protective factor against CU traits in males, supporting findings that increased maternal warmth and more specifically having a positive relationship characterized by respect with the maternal figure acts as a protective factor against developing CU traits in males (Bisby et al., 2017). Maternal care has also been associated with increased empathy in men (Lyons et al., 2017). Surprisingly, the factor accessing feelings of responsibility for the father appeared to be a risk factor for CU traits in females only. This interesting finding perhaps resonates with the fact that increased responsibility towards fathers may lead to dissatisfaction within a father-daughter relationship, which leads to the development of frustration and irritation in females and the development of CU traits (Cicerelli, 1983; Peisah et al., 1999). The feelings of frustration arising from the sense of responsibility could be exacerbated if daughters avoid communicating effectively with their fathers, during undesirable life-events (Punyanunt-Carter, 2007). If this pattern of dysfunctional behaviors is repeated over the years, this would explain the development of these personality traits. Together these findings are in agreement with previous research suggesting that the importance of family is perceived differently across genders (Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994). Thus this should also be reflected in intervention efforts focused on rectifying relationships with attachment figures to prevent/manage callous unemotional traits (Wright & Edginton, 2016). The literature also states that same sex parents tend to have more influence on their children’s behavior, resulting from mimicking the actions of same sex parents (Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2019). However, our findings contradict these studies and that of Steele and Mckinney (2019), which illustrated the continuing impact of same gender interactions (i.e., mother-daughter dyad) on emerging adults’ mental health. It might be that cultural differences explain the differences in findings as Steele and Mckinney’s (2019) sample comprised of predominantly Caucasian college students. Unfortunately the current sample’s ethnic background information was not collected, but our sample was more diverse with regard to age and included older individuals. This highlights the need for additional research on parental factors and CU traits in different ethnic and age groups.

Finally, another theoretical contribution of our study is that attachment dimensions accounted for the largest variance in CU traits compared to parental factors and this was the case for both genders. These findings are not surprising and can be explained by the fact that adult attachments can be shaped by more recent interpersonal relationships (e.g., partners) than parental relationships which seem to become less influential as the person develops other relationships (Fraley & Roisman, 2019). While primary attachment experiences remain important, secondary attachment relationships such as friends and romantic partners become more influential beyond childhood (Imran et al., 2020). In line with this stream of research our findings reveal that an individual’s attachment is not static but dynamic and remains an influential predictor for psychopathic traits, which provides meaningful insights regarding the need to examine CU traits in the context of multiple relationships during adulthood.

Limitations

The present study has a number of limitations that should be addressed. First, the current study failed to include other variables (e.g., separation, loss of an important relationship, adverse childhood experiences) that would help decipher the risk and protective factors related to psychopathic traits. Future studies should also take into account culture backgrounds as this would help interpret the findings. Secondly, the sample was a community based low-risk sample and research on high-risk individuals is needed to corroborate the same pattern of findings in individuals with higher levels of psychopathic traits, as CU traits have stronger associations with parental factors in high-risk samples (Bisby et al., 2017; Waller et al., 2019). Thirdly, the measures used in the current study were self-reports and future research should try to replicate the findings using clinical interviews, multiple informants (parental figure, and/or partner) and possibly collect data regarding attachment and CU traits over time (following a longitudinal design).

Conclusions

The present study aimed to determine the impact of attachment dimensions and parental factors on callous unemotional traits across genders in adults. Our findings highlight the unique contribution of attachment dimensions to callous unemotional traits, specifically that high attachment avoidance can be viewed as a risk factor, while low attachment anxiety can be considered a protective factor for callous unemotional traits in both genders, beyond childhood. Parental factors were less influential than attachment dimensions on callous unemotional traits and they were perceived differently across genders. Having a positive respectful relationship with the mother is a protective factor for males while increased perceived responsibility for the paternal figure appears as a risk factor for callous unemotional traits in females, highlighting the unique role of maternal and paternal factors.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1989). Attachment beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Witting, B. (1969). Attachment and exploratory behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In B. M. Foss (Ed.), Determinants of Infant Behavior IV. (pp.113–136).

Alzeer, S. M., Michailidou, M. I., Munot, M., & Kyranides, M. N. (2019). Attachment and parental relationships and the association with psychopathic traits in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.07.009.

Asscher, J. J., Van Vugt, E. S., Stams, G. J. J. M., Deković, M., Eichelsheim, V. I., & Yousfi, S. (2011). The relationship between juvenile psychopathic traits, delinquency and (violent) recidivism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(11), 1134–1143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02412.x.

Bisby, M. A., Kimonis, E. R., & Goulter, N. (2017). Low maternal warmth mediates the relationship between emotional neglect and callous-unemotional traits among male juvenile offenders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(7), 1790–1798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0719-3.

Blanchard, A., & Lyons, M. (2016). Sex differences between primary and secondary psychopathy, parental bonding, and attachment style. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 10(1), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000065.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Separation: Anxiety and anger. Vol. 2 of Attachment and loss. Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Loss: Sadness and depression. Vol 3 of Attachment and loss. Basic Books.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford Press.

Cicerelli, V. G. (1983). Adult children’s attachment and helping behaviour to elderly parents: A path model. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(4), 815–825. https://doi.org/10.2307/3517943.

Ciucci, E., Baroncelli, A., Franchi, M., Golmaryami, F. N., & Frick, P. J. (2014). The association between callous-unemotional traits and behavioral and academic adjustment in children: Further validation of the inventory of callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36(2), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-013-9384-z.

Daly, K. D., & Mallinckrodt, B. (2009). Experienced therapists’ approach to psychotherapy for adults with attachment avoidance or attachment anxiety. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(4), 549–563. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016695.

Eisenbarth, H., Demetriou, C. A., Kyranides, M. N., & Fanti, K. A. (2016). Stability subtypes of callous–unemotional traits and conduct disorder symptoms and their correlates. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1889–1901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0520-4.

Fanti, K. A., Colins, O. F., Andershed, H., & Sikki, M. (2017). Stability and change in callous-unemotional traits: Longitudinal associations with potential individual and contextual risk and protective factors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000143.

Fanti, K. A., Kyranides, M. N., Lordos, A., Colins, O. F., & Andershed, H. (2018). Unique and interactive associations of callous-unemotional traits, impulsivity and grandiosity with child and adolescent conduct disorder symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40, 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9655-9.

Fontaine, N. M., Rijsdijk, F. V., McCrory, E. J., & Viding, E. (2010). Etiology of different developmental trajectories of callous-unemotional traits. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(7), 656–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.014.

Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2019). The development of adult attachment styles: Four lessons. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.008.

Fraley, R. C., & Shaver, P. R. (1997). Adult attachment and the suppression of unwanted thoughts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(5), 1080–1091. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1080.

Frick, P. J. (2004). The inventory of callous–unemotional traits. Unpublished rating scale.

Frick, P. J., & White, S. F. (2008). The importance of callous-unemotional traits for the development of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x.

Frodi, A., Dernevik, M., Sepa, A., Philipson, J., & Bragesjö, M. (2001). Current attachment representations of incarcerated offenders varying in degree of psychopathy. Attachment & Human Development, 3(3), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730110096889.

Golmaryami, F. N., Vaughan, E. P., & Frick, P. J. (2021). Callous-unemotional traits and romantic relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110408.

Griffin, D. W., & Bartholomew, K. (1994). Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(3), 430–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.3.430.

Hare, R. D. (1996). Psychopathy: A clinical construct whose time has come. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 23(1), 25–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854896023001004.

Henschel, S., Nandrino, J. L., & Doba, K. (2020). Emotion regulation and empathic abilities in young adults: The role of attachment styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 156, 109763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.1097633.

Imran, S., Macbeth, A., Quayle, E., & Chan S. (2020). Secondary attachment and mental health in Pakistani and Scottish adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. e12280. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12280.

Kimonis, E. R., Cross, B., Howard, A., & Donoghue, K. (2013). Maternal care, maltreatment and callous-unemotional traits among urban male juvenile offenders. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(2), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9820-5.

Kimonis, E. R., Fanti, K. A., Frick, P. J., Moffitt, T. E., Essau, C., Bijttebier, P., & Marsee, M. A. (2015). Using self-reported callous-unemotional traits to cross-nationally assess the DSM-5 ‘with limited Prosocial emotions’ specifier. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(11), 1249–1261. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12357.

Kohlhoff, J., Mahmood, D., Kimonis, E., Hawes, D. J., Morgan, S., Egan, R., Niec, L. N., & Eapen, V. (2020). Callous–unemotional traits and disorganized attachment: Links with disruptive behaviors in toddlers. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51(3), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00951-z.

Kurdek, L. A. (2002). On being insecure about the assessment of attachment styles. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19(6), 811–834. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407502196005.

Kyranides, M. N., Fanti, K. A., & Panayiotou, G. (2016). The disruptive adolescent as a grown-up: Predicting adult startle responses to violent and erotic films from adolescent conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(2), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9520-z.

Kyranides, M. N., Fanti, K. A., Sikki, M., & Patrick, C. J. (2017). Triarchic dimensions of psychopathy in young adulthood: Associations with clinical and physiological measures after accounting for adolescent psychopathic traits. Personality Disorder: Theory, Research and Treatment, 8(2), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000193.

Kyranides, M. N., Fanti, K. A., Katsimicha, E., & Georgiou, G. (2018). Preventing conduct disorder and callous unemotional traits: Preliminary results of a school based pilot training program. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(2), 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0273-x.

Lyons, M. T., Brewer, G., & Bethell, E. J. (2017). Sex-specific effect of recalled parenting on affective and cognitive empathy in adulthood. Current Psychology, 36(2), 236–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9405-z.

Mack, T. D., Hackney, A. A., & Pyle, M. (2011). The relationship between psychopathic traits and attachment behavior in a non-clinical population. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(5), 584–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.05.019.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. The Guilford Press.

Peisah, C., Brodaty, H., Luscombe, G., Kruk, J., & Anstey, K. (1999). The parent adult-child relationship questionnaire (PACQ): The assessment of the relationship of adult children to their parents. Aging & Mental Health, 3(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607869956415.

Punyanunt-Carter, N. M. (2007). Using attachment theory to study communication motives in father–daughter relationships. Communication Research Reports, 24(4), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090701624213.

Ray, J. V., & Frick, P. J. (2020). Assessing callous-unemotional traits using the total score from the inventory of callous-unemotional traits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 49(2), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1504297.

Rose, J., McGuire-Snieckus, R., Gilbert, L., & McInnes, K. (2019). Attachment aware schools: The impact of a targeted and collaborative intervention. Pastoral Care in Education, 37(2), 162–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2019.1625429.

Rothbaum, F., & Weisz, J. R. (1994). Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.55.

Ruiz-Hernández, J. A., Moral-Zafra, E., Llor-Esteban, B., & Jiménez-Barbero, J. A. (2019). Influence of parental styles and other psychosocial variables on the development of externalizing behaviors in adolescents: A systematic review. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 11(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2018a11.

Schmitt, D. P., & Jonason, P. K. (2015). Attachment and sexual permissiveness: Exploring differential associations across sexes, cultures, and facets of short-term mating. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46(1), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022114551052.

Seara-Cardoso, A., Neumann, C., Roiser, J., McCrory, E., & Viding, E. (2012). Investigating associations between empathy, morality and psychopathic personality traits in the general population. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(1), 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.08.029.

Simmons, B. L., Gooty, J., Nelson, D. L., & Little, L. M. (2009). Secure attachment: Implications for hope, trust, burnout, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(2), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.585.

Simpson, J. A., Kim, J. S., Fillo, J., Ickes, W., Rholes, W. S., Oriña, M. M., & Winterheld, H. A. (2011). Attachment and the management of empathic accuracy in relationship-threatening situations. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(2), 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210394368.

Steele, E. H., & McKinney, C. (2019). Emerging adult psychological problems and parenting style: Moderation by parent-child relationship quality. Personality and Individual Differences, 146, 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2018.04.048.

Van Der Voort, A., Juffer, F., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2014). Sensitive parenting is the foundation for secure attachment relationships and positive social-emotional development of children. Journal of Children's Services, 9(2), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-12-2013-0038.

Van Der Zouwen, M., Hoeve, M., Hendriks, A. M., Asscher, J. J., & Stams, G. J. J. (2018). The association between attachment and psychopathic traits. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 43, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.09.002.

Waller, R., Wagner, N., Flom, M., Ganiban, J., & Saudino, K. (2019). Fearlessness and low social affiliation as unique developmental precursors of callous-unemotional behaviors in preschoolers. Psychological Medicine, 51, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171900374X.

Walsh, H. C., Roy, S., Lasslett, H. E., & Neumann, C. S. (2019). Differences and similarities in how psychopathic traits predict attachment insecurity in females and males. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 41(4), 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9704-4.

Wright, B., & Edginton, E. (2016). Evidence-based parenting interventions to promote secure attachment. Global Pediatric Health, 3, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X16661888.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Output of analysis conducted available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

First author presented idea and supervised the findings of this work. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

No identifiable information was collected.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kyranides, M.N., Kokkinou, A., Imran, S. et al. Adult attachment and psychopathic traits: Investigating the role of gender, maternal and paternal factors. Curr Psychol 42, 4672–4681 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01827-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01827-z