Abstract

Research addressing relationship satisfaction is a constantly growing area in the social sciences. The aim of the present investigation was to examine the similarities and differences between the seven-item Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) and the single-item measure of relationship satisfaction (RAS-1), using proximal and distal constructs as correlates. Two studies using two independent samples were conducted, assessing more proximal constructs, such as love and sex mindset in Study 1 (N = 380; female = 195) and more distant ones, such as loneliness and problematic pornography use in Study 2 (N = 703; female = 360). Structural equation modeling revealed that love (βRAS-1 = .55; p < .01; βRAS = .71; p < .01), sex mindset beliefs (βRAS-1 = .18; p < .01; βRAS = .13; p < .01) and loneliness (βRAS-1 = −.35; p < .01; βRAS = −.37; p < .01) had significant positive and negative associations with RAS and RAS-1, respectively; while problematic pornography use did not. These results suggest that RAS-1 may be an equally adequate instrument for measuring relationship satisfaction as the RAS with respect to proximal and distal correlates. Thus, RAS-1 is recommended to be used in large-scale studies when the number of items is limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Relationship satisfaction is defined as an interpersonal evaluation of the positivity of feelings for one’s romantic partner and attraction to the relationship; it is the degree to which individuals feel that their partner fulfills their needs (Rusbult and Buunk 1993). Research in relationship satisfaction is a permanently growing area in psychology and other areas of social sciences as well (e.g., Graham et al. 2011; Malouff et al. 2014; Malouff et al. 2010; Wright et al. 2017). Relationship satisfaction is associated with diverse constructs such as sexual satisfaction (Byers 2005; Schwartz and Young 2009; Sprecher 2002), attachment (Butzer and Campbell 2008; Feeney 2002; Pistole 1989), pornography use (Stewart and Szymanski 2012; Szymanski and Stewart-Richardson 2014; Szymanski et al. 2015), well-being (Apt et al. 1996; Davison et al. 2009), and loneliness (Hawkley et al. 2008; Mellor et al. 2008). In addition, a decline in relationship satisfaction over time was shown linked to poorer and more negative communication in studies with married couples (Lavner and Bradbury 2012), and it may also be linked to parenting influences. The children of parents who showed less warmth (e.g., gave less praise) and who were harsher, reported lower relationship satisfaction as young adults (Parade et al. 2012).

One of the most frequently used instruments for measuring relationship satisfaction is the Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS, Hendrick 1988) which was translated to and validated in several languages (e.g., Dinkel and Balck 2006; Martos et al. 2014; Rask et al. 2010) and is one of the most commonly used scales of this kind (Graham et al. 2011; Malouff et al. 2010; Malouff et al. 2014; Wright et al. 2017). Despite the common use of the RAS (Dinkel and Balck 2006; Hendrick et al. 1998; Rask et al. 2010; Renshaw et al. 2011; Sander and Böcker 1993; Vaughn and Matyastik Baier 1999), no prior study has ever examined whether a shorter, one-item version of this scale may be an adequate measure of relationship satisfaction. Therefore, the aim of the present research was to develop a one-item measure of relationship satisfaction (RAS-1) based on a well-studied scale (RAS) and examine its validity in relation to theoretically-relevant constructs (i.e., love, sex mindset beliefs, loneliness, and problematic pornography use).

The Association of Relationship Satisfaction and Love

To ensure that the RAS-1 reliably and validly assesses the same construct as the longer version of it, its associations with theoretically relevant variables must be examined on independent samples (Marsh et al. 2005). One key variable that should be considered in the case of relationship satisfaction is love. Romantic love has numerous definitions (e.g., Sternberg 1997; Lee 1973). By the definition of Rubin (1970), romantic love is “an attitude held by a person toward a particular other person, involving predispositions to think, feel, and behave in certain ways toward that other person.” Several studies have shown that there is a moderate-to-strong association between love and relationship satisfaction. In his studies, Sternberg (1997) found correlations ranging from 0.67 to 0.86 between relationship satisfaction and all three subscales of his triangular love scale, in contrast to the moderate, 0.59 correlation between relationship satisfaction and the Rubin Love Scale. While this association was weaker, it still suggests a substantial association between the two constructs. Similarly, Fletcher et al. (2000) reported a strong, positive association between relationship satisfaction and love (over 0.60), using another measure of relationship satisfaction (Perceived Relationship Quality Components Inventory).

Even if love and relationship satisfaction are strongly associated, they refer to different psychological phenomena. Relationship satisfaction can be considered as a broader construct referring to a global cognitive evaluation of the relationship itself in which affective components such as romantic love is only one of the important constituents among other aspects including specific affects, beliefs, and attitudes (Meeks et al. 1998). In sum, love is not the same as relationship satisfaction, but it is an important contributor to relationship satisfaction, and thus, it could serve as an appropriate affective validity measure of RAS-1.

Associations between Relationship Satisfaction and Beliefs about the Malleability of Sexual Life

Besides the affective components of relationship satisfaction, it includes some cognitive and belief-based aspects as well (Meeks et al. 1998). Therefore, it may be reasonable to examine not only affect-related (i.e., love), but cognitive constructs as well with respect to relationship satisfaction. One cognitive, belief-based variable that may be an important correlate of relationship satisfaction is the sex mindset.

According to the Mindset Theory (Dweck 2012; Dweck et al. 1995a, b), people construct different beliefs about the changeability of personal attributes (e.g., intelligence, personality). When it comes to romantic relationships, fixed sex mindset beliefs refer to the unchangeable nature of sexual life, resulting in smaller amount of effort to improve it or to try out new strategies, which in turn can lead to lower levels of sexual and relationship satisfaction (Bőthe et al. 2017). On the contrary, individuals with a growth sex mindset believe that their sexual life can be improved through making efforts or engaging in new strategies. A potential consequence of this belief may be the experience of more frequent novelty in their sexual life leading to higher levels of sexual and relationship satisfaction (Bőthe et al. 2017). These results are in line with recent multi-method findings. According to Maxwell et al.’s (2017), people who believe that sexual satisfaction is something that requires effort to maintain–sexual growth beliefs or growth sex mindset–reported higher sexual and relationship satisfaction. This result emerged in multiple conditions, such as in normal day-to-day life or in couples undergoing the transition to parenthood, which is a period associated with difficulties maintaining sexual satisfaction and frequency. In sum, it can be assumed that growth sex mindset beliefs will have positive associations with relationship satisfaction in the present study as well (Bőthe et al. 2017; Maxwell et al. 2017).

Associations between Relationship Satisfaction and Loneliness and Problematic Pornography

Besides the strongly related cognitive and affective correlates, there are some less strongly related, but still important correlates of relationship satisfaction. From an interpersonal perspective, loneliness can be described as an unpleasant situation or experience in which the individual’s social relationships are deficient qualitatively or quantitatively (de Jong-Gierveld 1987; de Jong-Gierveld 1998; Perlman and Peplau 1981). While loneliness is a subjective feeling, certain objective, interpersonal factors, such as living alone, are strong predictors of it (e.g., de Jong-Gierveld 1998). Loneliness is not equal to being alone; therefore, individuals who are in a romantic relationship can also experience feelings of loneliness. Thus, the perceived quality of one’s relationship (i.e., relationship satisfaction) might be a result of feeling lonely in a given relationship. For example, according to Hawkley et al. (2008), lower levels of loneliness were associated with higher levels of satisfaction with one’s marriage. However, if the spouse did not serve as a confidant, being married was unrelated to loneliness, indicating that feeling higher levels of loneliness in a relationship as a result of potential communication problems or distrust may lead to lower levels of relationship quality and relationship satisfaction.

From a risk-behavior perspective, pornography use, and problematic pornography use, in particular, may have negative associations with one’s relationship satisfaction. In most cases, pornography use is not problematic as numerous studies suggest that recreational use of pornography does not have a negative effect on users, and it might even positively influence sexual life (Bőthe et al. 2020b; Hald et al. 2015; McKee 2007; Rogala and Tydén 2003). However, in some cases, pornography use can become problematic and can have adverse effects on the user’s life (e.g., Bőthe et al. 2018; Gwinn et al. 2013; Pyle and Bridges 2012; Willoughby et al. 2015; Wright et al. 2017). Problematic pornography use has been shown to be negatively, although weakly associated with romantic relationship outcomes, such as relationship satisfaction, relationship quality, and sexual satisfaction (Stewart and Szymanski 2012; Szymanski and Stewart-Richardson 2014; Szymanski et al. 2015). However, results concerning these associations are controversial as some studies showed no associations between pornography consumption and relationship satisfaction (Vaillancourt-Morel et al. 2019). One way to reconcile these conflicting results may be to consider the way pornography consumption was measured: it is important to distinguish between the frequency and severity (e.g., problematic use) of pornography use (Bőthe et al. 2020a, 2020b; Gola et al. 2016). According to research, the severity of pornography consumption (e.g., problematic use) is more likely to be associated with lower relationship satisfaction (e.g., Stewart and Szymanski 2012) than the frequency of pornography use in itself (e.g., Voon et al. 2014). In sum, in contrast to recreational pornography use, problematic pornography use had negative but weak associations with relationship satisfaction.

Benefits and Limits of a One-Item Version to Assess Relationship Satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction, similarly to sexual satisfaction (Mark et al. 2013), implies a global evaluation of the quality of one’s relationship as a whole, unitary construct; thus, this global cognitive evaluation might be adequately represented by a single-item measure. For such constructs as general relationship or sexual satisfaction, using a single-item construct can be more adequate than using several, highly similar items. Scales, including numerous similar items, can be repetitive and can reduce respondents’ motivation in continuing the fill-out process. Based on prior studies using single-item measures (e.g., Cunny and Perri 1991; Dolan et al. 2015; Konrath et al. 2014; Konrath et al. 2018; Mark et al. 2013; Nagy 2002; Robins et al. 2001), some further advantages of such instruments can be considered. These measures might be easier to use than full-length scales (1) when the researcher has limited resources, sample size or time (e.g., Cunny and Perri 1991); (2) when respondents have a limited attention span (e.g., online surveys; Konrath et al. 2014; Konrath et al. 2018), or (3) in diary studies where the same construct has to be assessed multiple times (e.g., Konrath et al. 2014). Single-item measures are also more suitable for (4) pilot testing new theories or methods (e.g., Konrath et al. 2018), and (5) they are easier to interpret (e.g., Dolan et al. 2015). They are overall (6) less expensive and easier to carry out than full-length surveys (e.g., Dolan et al. 2015); they may also be (7) more flexible and (8) have more face validity than full-length measures (e.g., Nagy 2002).

Nevertheless, there are studies in which the use of longer scales may be more adequate. It is important to note that single-item measures can only be adequate when an overall score of the given concept can be easily given. Thus, this method may not be feasible in the case of personality traits, skills, or symptoms (e.g., Konrath et al. 2018). Also, the use of longer scales is suggested when the small differences between the participants can have high importance (Bőthe et al. 2020a). For example, the original, full-length RAS may be advantageous for a more in-depth analysis of one’s relationship satisfaction, as it may give insight into several aspects of the construct such as the individual’s expectations (“To what extent has your relationship met your original expectations?”) and possible negative evaluations (“How often do you wish you hadn’t gotten into this relationship?”). In sum, both the RAS and the RAS-1 have their advantages and disadvantages, and both scales have their niches in scientific studies.

The Aims of the Present Studies

Based on prior successful single-item measures (e.g., Cunny and Perri III 1991; Dolan et al. 2015; Konrath et al. 2014; Konrath et al. 2018; Mark et al. 2013; Nagy 2002; Robins et al. 2001) and the aforementioned practical benefits, the aim of the present study was to develop and validate a single-item measure of relationship satisfaction by investigating the similarities and dissimilarities between the seven-item RAS and a single-item measure of relationship satisfaction (RAS-1) in terms of reliability and validity. To examine the convergent validity of the single-item version in contrast to the longer one, affective and cognitive variables as romantic love and sex mindset (Study 1) and loneliness and problematic pornography use (Study 2) were utilized. We used two independent samples for the two studies to strengthen the reliability of results, which is essential, especially in the time of the current replication crisis (Shrout and Rodgers 2018).

Study 1 - Examining the Associations of the Single-Item Relationship Satisfaction Measures (RAS-1) in Relation to Love and Sex Mindset

The aim of Study 1 was to investigate the associations of relationship satisfaction with love and sex mindset beliefs. According to previous literature, relationship satisfaction had a moderate-to-strong, positive association with love (e.g., Acker and Davis 1992; Fricker and Moore 2002), and a weak-to-moderate, positive association with sex mindset beliefs (Bőthe et al. 2017; Maxwell et al. 2017). In the present study, two models were tested: The first model examined the associations between love, sex mindset beliefs, and relationship satisfaction as measured by the original RAS, while the second model examined the associations between love, sex mindset beliefs, and relationship satisfaction as measured by the single-item RAS-1.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The current study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Eötvös Loránd University (2015/359). The study was advertised on a public social media page unrelated to the topic of this study. Participants who were 18 years or older were eligible to participate, and informed consent was obtained before data collection. Participants took, on average, 15 minutes to complete the survey. Since relationship satisfaction can only be assessed among those who are currently in a relationship, we excluded participants who reported being single (n = 274). This exclusion resulted in a total of 380 participants (female = 195; 48.7%). The mean age was 30.21 years (SD = 12.01), ranging from 18 to 66 years old. The sample varied in terms of educational attainment: 3.7% completed primary school (n = 14), 16.8% completed high school (n = 64), 31.8% were currently in college (n = 121), 17.4% received their bachelor’s degree (n = 66), 4.7% were currently enrolled in an undivided program at university (n = 18), 9.7% had received a degree from an undivided program (n = 37), 3.4% were currently enrolled in a master’s program (n = 13), and 12.4% had received a master’s degree (n = 47). Participants were from a wide range of geographical areas: 39.5% reported residing in the capital (n = 150), 44.5% in towns or county towns (n = 169), 10.5% in villages (n = 40), and 5.5% abroad (n = 21).

Measures

Relationship Satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction was assessed in two ways. The first was via the original seven-item Relationship Assessment Scale (Hendrick 1988; Martos et al. 2014). Participants responded to each item on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (“not satisfied”) to 5 (“very satisfied”). The second method was via a single item of the same Relationship Assessment Scale: “In general, how satisfied are you with your relationship?”. Compared to other items of the scale (Table 1), this item had the highest correlation with the full scale (r(378) = .86, p < .01), had the highest standardized factor loadings, had the highest corrected item-total correlation, had the lowest skewness and kurtosis values, and best covered the content of the definition of relationship satisfaction, which suggested that it may be used as a representative item for the overall construct of relationship satisfaction. Descriptive statistics and measures of internal consistency for both the full and single-item Relationship Assessment Scale are reported in Table 2.

Sex Mindset

The Sex Mindset Scale assesses people’s beliefs about the extent to which their sexual lives can be changed (Bőthe et al. 2017). The scale consists of five items (e.g., “You have a certain type of sexual life and you really can’t do much to change it.”), of which three are reverse coded. For each item, participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement on a six-point scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly agree”) to 6 (“strongly disagree”). Lower scores on the scale represent relatively more fixed mindsets regarding one’s sexual life, whereas higher scores on the scale represent relatively more malleable mindsets regarding one’s sexual life. Descriptive statistics and measures of internal consistency for this scale are displayed in Table 2.

Love

The Rubin Love Scale was used to assess romantic love (Orosz et al. 2015; Rubin 1970). The scale consists of 13 items (e.g., “I would do almost anything for my partner”). Participants rated each item on a nine-point scale, ranging from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 9 (“completely agree”). Higher scores represent greater levels of romantic love in the relationship. Descriptive statistics and measures of internal consistency are shown in Table 2.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 21.0 was used to compute descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis) as well as correlations between relationship satisfaction, sex mindset, and love. In line with Muthén and Kaplan’s (1985) suggestions, normality was assessed for each of these variables based on skewness, and kurtosis. Based on Muthén and Kaplan’s (1985) rather strict suggestions, the normality thresholds for skewness and kurtosis should be between −1 and + 1. However, according to Curran et al.’s (1996) suggestions, skewness values >2 and kurtoses values >7 can cause problems in the analyses; thus, these more permissive, moderate values may be acceptable. Internal consistency was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha (Nunnally 1978) and McDonald’s omega (Dunn et al. 2014; McDonald 1999) for each of the scales for the multi-item scales (≥ .80 for good reliability, ≥ .70 for acceptable reliability). To assess the reliability of the single-item relationship satisfaction measure (RAS-1), we used the correction for attenuation formula originally presented by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) and then reintroduced by Wanous and Reichers (1996). This formula is widely used in the literature when assessing the reliability of single-item measures (e.g., Christophersen and Konradt 2011; Dolbier et al. 2005; Postmes et al. 2013; Wanous et al. 1997; Wanous and Hudy 2001). Based on the correlation between the RAS and RAS-1, the reliability of the RAS, and the estimated “true” correlation between RAS-1 and RAS (r = 1), the reliability of the RAS-1 can be estimated by this solving the formula (Wanous and Reichers 1996).

Initially, the RAS was examined in both studies to choose the best item representing relationship satisfaction. Based on the guidelines of Marsh et al. (2005), Orosz et al. (2016), and Bőthe et al. (2020a), each item was evaluated by the following criteria: (a) having the highest standardized factor loading, (c) having the highest corrected item-total correlation, (b) having the lowest skewness and kurtoses values. Apart from the reported statistical information, we also considered the theoretical adequacy of the items (as proposed by Hu and Bentler 1998; Marsh et al. 2004; Morin et al. 2015).

Mplus 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2015) was used to conduct structural equation modeling (SEM) to explore the associations between relationship satisfaction (as measured by both the full and single-item Relationship Assessment Scale), sex mindset, and love. Due to severe floor or ceiling effects (as indicated by kurtosis and skewness values), items were treated as categorical indicators, and the mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV) was applied (Finney and DiStefano 2006).

When assessing the models, multiple goodness of fit indices were observed (Brown 2015) with good or acceptable values based on the following thresholds (Hu and Bentler 1998; Marsh et al. 2005). Regarding the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), values higher than .95 indicated that a model had a good fit, while values higher than .90 indicated that a model had an acceptable fit. In the case of the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the same thresholds can be applicable (≥ .95 for good model fit, ≥ .90 for acceptable model fit). Regarding the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its 90% confidence interval (90% CI), a model can be considered good if its RMSEA value is below .06, whereas it can be considered acceptable if said value is below .08.

Results

Descriptive statistics, reliability indices, and correlations between the examined variables can be seen in Table 2. The internal consistencies of the applied scales were appropriate. The single-item measure of relationship satisfaction had a strong, positive association with the original, seven-item scale and demonstrated adequate reliability based on the correction for attenuation formula. Moderate, positive correlations were found between sex mindset beliefs and both versions of relationship satisfaction measurements. There were strong, positive correlations between the two versions of the relationship satisfaction measures and love.

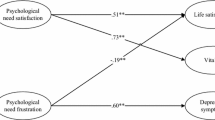

Using SEM, two models examined the associations between relationship satisfaction, sex mindset beliefs, and love, one model for each measurement method of relationship satisfaction. The models with standardized estimates are presented in Fig. 1. In Model 1a, the original RAS was used to measure relationship satisfaction. The fit indices were acceptable (CFI = .957; TLI = .952; RMSEA = .067 [90% CI .061–.073]). Sex mindset beliefs (β = .13; p = .005) and love (β = .71; p < .001) had positive associations with relationship satisfaction (RAS), with love having a strong, and sex mindset beliefs having a weak effect size. The explained variance of relationship satisfaction was 56.0%.

The models of sex mindset beliefs, love and relationship satisfaction, using two methods to assess relationship satisfaction (N = 380). Note. SMS = Sex Mindset Scale; RLS = Rubin Love Scale; RAS-1 = single-item relationship assessment; RAS = Relationship Assessment Scale. One-headed arrows represent standardized regression weights, two-headed arrows represent covariances. All variables presented in ellipses are latent variables. For the sake of simplicity, indicator variables related to them were not depicted in this figure. The percentages indicate the explained variance of the given variable. All associations were significant at p < .01

In Model 1b, the single-item version of RAS was used, and the fit indices were also acceptable (CFI = .965; TLI = .960; RMSEA = .070 [90% CI .062–.078]). Both sex mindset beliefs (β = .18; p < .001) and love (β = .55; p < .001) had positive associations with relationship satisfaction (RAS-1), with love having a moderate, and sex mindset beliefs having a weak effect size. The explained variance of relationship satisfaction was 37.9%.

Taken together, in both models, sex mindset beliefs had a weak, positive association with relationship satisfaction, while in the case of love, the effect sizes were somewhat different: Love had a stronger association with relationship satisfaction when the seven-item relationship satisfaction scale was applied presumably as a result of RAS including an item explicitly assessing the level of love.

Study 2 - Examining the Associations of the Single-Item Relationship Satisfaction Measures (RAS-1) in Relation to Loneliness and Problematic Pornography Use

The aim of Study 2 was to investigate the associations between loneliness, problematic pornography use, and relationship satisfaction. According to previous literature, relationship satisfaction had a weak, positive association with loneliness (e.g., Hawkley et al. 2008; Mellor et al. 2008) and a weak, negative association with problematic pornography use (e.g., Bőthe et al. 2017; Willoughby et al. 2015; Wright et al. 2017). In the present study, similarly to Study 1, two models were tested: The first model examined the associations between loneliness, problematic pornography use, and the original, seven-item RAS, while the second model examined the associations of loneliness, problematic pornography use, and relationship satisfaction as measured by the single-item RAS-1.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The guidelines and methods for this study were the same as Study 1; this study used a sample independent from Study 1. Participants were required to 1) be in a romantic relationship, and 2) have watched pornography at least once in the past 6 months. Based on these criteria, 847 participants were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 703 (female = 360; 51.2%) participants. Participants’ mean age was 25.61 years (SD = 8.00) and ranged from 18 to 64 years old. Again, the sample varied in terms of educational attainment: 1.6% completed primary school (n = 11), 9.0% had an unfinished degree in high school or were currently completing it (n = 63), 25.9% completed high school (n = 182), 39.3% had an unfinished degree in college or university or were currently completing it (n = 276), and 24.3% had a college or university degree (n = 171). Finally, participants reported residing in a wide range of geographical areas: 31.6% reported residing in the capital (n = 222), 55.0% in towns or county towns (n = 387), and 13.4% in villages (n = 94).

Measures

Relationship Satisfaction

We used the same scale that was used in Study 1. Further corroborating the findings in Study 1, Item 2 had the highest correlation with the full scale (r(701) = .86, p < .01), had the highest standardized factor loadings and had the highest corrected item-total correlation in this study as well (Table 3). Descriptive statistics and measures of internal consistency for both the full and single-item Relationship Assessment Scale for this study are reported in Table 4.

Loneliness

To assess loneliness, participants completed an 8-item version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Bőthe et al. 2018). For each item (e.g., “How often do you feel that you are no longer close to anyone?”), participants indicated their level of agreement on a four-point scale, ranging from 1 (“I often feel this way”) to 4 (“I never feel this way”). Descriptive statistics and measures of internal consistency are reported in Table 4.

Problematic Pornography Use

Perceived problematic pornography use was assessed using the Cyber Pornography Use Inventory (CPUI) (Bőthe et al. 2015; Grubbs et al. 2010). The scale consists of 12 items, composed of three dimensions with four items each: negative feelings (e.g., “I feel depressed after viewing pornography online.”), social anxiety (e.g., “I avoid situations in which my pornography usage could be exposed or confronted.”) and compulsion (e.g., “I have problems controlling my use of online pornography.”). For each item, participants indicated their level of agreement on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (“completely disagree”) to 7 (“completely agree”). Descriptive statistics and measures of internal consistency for this scale are displayed in Table 4.

Statistical Analysis

As in Study 1, SPSS 21.0 was used to compute the descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis) and correlations between key variables. Also, as in Study 1, Mplus 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2015) was used to conduct SEM to explore the associations between relationship satisfaction measures (both the full seven-item and single-item Relationship Assessment Scale), loneliness, and problematic pornography use. The same fit indices and guidelines as Study 1 were applied.

Results

Descriptive statistics, reliability indices, and correlations between the examined variables are shown in Table 4. The internal consistencies of the scales were adequate. There was a strong, positive association between the two versions of the relationship assessment scale, and the RAS-1 had adequate reliability based on the correction for attenuation formula, suggesting that RAS-1 could be a reliable measure of relationship satisfaction. Furthermore, there were weak, negative correlations between problematic pornography use and the two relationship satisfaction assessment scales. Moderate, positive associations were observed between loneliness and problematic pornography use. We again used two models to explore the associations between relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and problematic pornography use, with one model for each measurement method of relationship satisfaction. The two versions of relationship satisfaction. The models with standardized estimates are shown in Fig. 2. In Model 2a, the full seven-item RAS was used as the relationship satisfaction measure. The fit indices were good (CFI = .982; TLI = .980; RMSEA = .041 [90% CI .036–.045]). Loneliness had a negative, moderate association with relationship satisfaction (RAS) (β = −.35; p < .001), whereas the association between problematic pornography use and relationship satisfaction was not significant. The explained variance of relationship satisfaction was 15.0%.

The associations between problematic pornography consumption, loneliness and relationship satisfaction using two methods of measurement (N = 703). Note. CPUI = Cyber Pornography Use Inventory. UCLA = University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale. RAS-1 = single-item relationship assessment. RAS = Relationship Assessment Scale. All variables presented in ellipses are latent variables. For the sake of simplicity, indicator variables related to them were not depicted in this figure. The percentages indicate the explained variance of the given variable. Dashed lines indicate non-significant associations, all other associations were significant at p < .01

Model 2b included the single-item version of relationship assessment (RAS-1) and the fit indices were also good (CFI = .985; TLI = .983; RMSEA = .042 [90% CI .037–.048]). Loneliness had a negative, moderate association with relationship satisfaction (β = −.37; p < .001), while the association between problematic pornography use and relationship satisfaction was not significant. The explained variance of relationship satisfaction was 15.5%.

In sum, the effect sizes were similar in the two examined models. Loneliness was a negative, moderate predictor of relationship satisfaction, whereas problematic pornography use did not have a significant association with relationship satisfaction. These results suggest that the single-item measure of relationship satisfaction may be a short, easy-to-use alternative of the original Relationship Assessment Scale.

General Discussion

The aim of the present two-study investigation was to develop and examine the reliability and validity of a single-item relationship satisfaction measure (RAS-1) compared to the seven-item Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS). For this purpose, four models were examined across two studies using independent samples to investigate whether similar results could be obtained when using RAS-1 instead of RAS. According to the results of the present studies, RAS-1 was strongly and positively associated with RAS in both studies, indicating adequate concurrent validity. Moreover, similar relationship patterns were observed in the case of the RAS-1, the RAS and related constructs (i.e., sex mindset, problematic pornography use, and loneliness), demonstrating appropriate convergent validity. However, when the associations between the RAS-1, the RAS, and love were observed, RAS had a stronger association with love than RAS-1, potentially due to criterion contamination.

Applying a single-item measure to assess a psychological construct or characteristic is common, due to short administration time and limited requirements of resources, specifically in the cases of large-scale surveys (Loo 2002). In finding that RAS-1 had a strong, positive association with the original, seven-item RAS is in line with a previous study examining the reliability of a single-item sexual satisfaction measurement (Mark et al. 2013). According to Mark et al. (2013), the single-item measurement of sexual satisfaction may be considered an adequate measure of sexual satisfaction in terms of reliability. Moreover, RAS-1 showed high levels of concurrent validity with the full-length RAS, indicating that the two instruments assess the same construct (i.e., relationship satisfaction). As advised by the developers of the single-item sexual satisfaction measurement (Mark et al. 2013), the RAS-1 may be particularly useful when survey efficiency is a priority, for instance, when quick data gathering and easy administration of large-scale surveys is necessary, or when resources are limited.

The Validity of RAS-1 in Association with Theoretically-Relevant Correlates

A further question posed in this research project was whether a single-item measure of relationship satisfaction might be a valid indicator of relationship satisfaction. Employing affective, cognitive, and interpersonal constructs, the results suggested that the RAS-1 had adequate convergent validity in terms of its associations with love, sex mindset, loneliness, and problematic pornography use.

The association between the original RAS and romantic love was strong and positive, whereas the association between RAS-1 and romantic love was moderate-to-strong, with a slightly smaller effect size. There may be several ways to interpret this difference between the two types of relationship satisfaction measures, but only the most prominent are mentioned here. First, while RAS-1 had a strong, positive association with the full-length RAS scale and thus, represents the construct properly, using the full-length RAS exposes participants to multiple facets of relationship satisfaction. As a result, participants completing the full-length RAS may have thought more thoroughly about the quality of their relationship, leading to more similar responses in the romantic love measure. Another possibility is that due to the full-length RAS containing an item that refers to love (“How much do you love your partner?”), it may have led to criterion contamination when assessing the scale’s association with love.

The cognitive construct, sex mindset beliefs, showed consistent associations with both RAS-1 and the full-length RAS. Prior research suggests that people’s beliefs about the malleability of their sexual lives are a predictor of relationship satisfaction: people who report a growth sex mindset believe that their sexual lives can be improved, are more likely to try new strategies, tend to have higher sexual satisfaction, and as a result, experience higher relationship satisfaction (e.g., Bőthe et al. 2017). In addition, findings from six studies with different methodologies (e.g., diary studies, experimental studies) conducted by Maxwell et al. (2017) all point to the same result. We were able to replicate this pattern of results using both RAS-1 and the full-length RAS. In both Study 1 and Study 2, there was a low to moderate, positive association between growth sex mindset beliefs and relationship satisfaction.

Our measure of loneliness had negative, moderate associations with both RAS-1 and the full-length RAS. These results are in line with previous studies suggesting that perceived relationship or marriage quality is associated with loneliness (Hawkley et al. 2008; Mellor et al. 2008). It is also possible that both lower relationship satisfaction and loneliness are a result of a third factor, such as communication problems or distrust in the relationship (Hawkley et al. 2008).

A potential risk-behavior construct, problematic pornography use, was also examined, as prior studies have shown that it is negatively but weakly associated with relationship outcomes such as relationship satisfaction (e.g., Stewart and Szymanski 2012; Szymanski and Stewart-Richardson 2014). However, in the present study, problematic pornography use was associated with neither measure of relationship satisfaction (neither RAS-1 nor RAS). This result stands in contrast to a meta-analysis by Wright et al. (2017), examining 50 studies on the association between pornography consumption and relationship satisfaction, in which they found that a higher rate of pornography consumption was associated with lower levels of relationship and sexual satisfaction. However, there are a few differences between this study and Wright et al.’s meta-analysis (Wright et al. 2017) that should be noted: in the meta-analysis, the association was only found among men, relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction were merged into a single measure, and they did not explicitly delineate whether their operationalization of pornography consumption included frequency of use and/or whether consumption of problematic pornography was included in the construct. A recent review by Vaillancourt-Morel et al. (2019) highlights the importance of gender and the context in which pornography is consumed as important variables to consider when interpreting the associations between pornography use and relationship satisfaction: men’s higher frequency of pornography use is more negatively associated with lower relationship satisfaction than women’s higher frequency of pornography use. In addition, larger between-partner discrepancies in pornography use, attitudes towards pornography, and secretive and solitary use of pornographic material can also result in lower levels of relationship satisfaction.

Furthermore, different measures of problematic pornography use may result in different relationship patterns. For example, in the study of Bőthe et al. (2017), the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS) was applied to assess the level of problematic pornography use, while the Cyber-Pornography Use Inventory (CPUI) was employed in the present study. The PPCS assesses problematic pornography use via six factors (i.e., tolerance, salience, mood modification, conflict, withdrawal, and relapse), while the CPUI assesses problematic pornography use via three factors (i.e., negativity towards viewing online pornography, compulsivity, and social anxiety). These two scales measure different aspects of problematic pornography use: the conflict factor of PPCS includes items referring to sexual or relationship problems, while the CPUI does not cover this topic. In Bőthe et al.’s (2017) study, using the PPCS, negative, weak associations between relationship satisfaction and problematic pornography use were reported (e.g., Bőthe et al. 2017). However, in the present study, using the CPUI, no associations were found between problematic pornography use and relationship satisfaction. Therefore, it is possible that the dissimilarity as mentioned above between the measures could contribute to the mixed results regarding the associations of relationship satisfaction and problematic pornography use.

Potential Applications of the Single-Item Relationship Satisfaction Measure (RAS-1)

Previous research (e.g., Cunny and Perri 1991; Dolan et al. 2015; Konrath et al. 2014; Konrath et al. 2018; Mark et al. 2013; Nagy 2002; Robins et al. 2001) has shown that single-item measures have numerous advantages over full-length measures, and could be more appropriate when resources, sample size, and/or time are limited (e.g., Cunny and Perri 1991). Also, single-item measures such as the RAS-1 may be more suitable for online surveys when respondents have a limited attention span (Konrath et al. 2014; Konrath et al. 2018) or when the same construct has to be assessed multiple times, such as in diary studies (e.g., Konrath et al. 2014). They are also more suitable for pilot testing new theories or methods (e.g., Konrath et al. 2018) and are easier to interpret (e.g., Dolan et al. 2015). In addition, they may be more flexible and have more face validity than full-length measures (e.g., Nagy 2002). However, the use of the full RAS is advised when the research calls for a more complex examination of relationship satisfaction as a construct, as opposed to acquiring a more general assessment of relationship satisfaction (in which case RAS-1 would be sufficient).

Limitations and Future Directions

The current studies have several limitations that raise interesting questions for future research. First, we utilized cross-sectional research designs, and as a result, cannot infer causality from the present results. Reverse associations between the examined variables are also possible (e.g., relationship satisfaction may have an effect on loneliness). Moreover, confounding variables can also play an important role in the aforementioned associations (such as the moderating role of gender or secrecy about use in the case of pornography use – Vaillancourt-Morel et al. 2019). Another limitation is that since all the measures were self-reported, certain biases (e.g., social desirability bias) may have affected participants’ responses. It is also worth noting that the applied samples were not representative (e.g., culture and age), limiting the generalizability of the findings.

It is also important to note that while single-item measures are increasingly used to examine complex constructs, and some reliabilities can be estimated (such as test-retest reliability), these measures do not allow for estimation of some more complex reliabilities, such as internal consistency or factor structure (Mark et al. 2013) and the captured variance may also be affected. To corroborate the reliability and validity of the RAS-1, further studies are needed in different contexts (e.g., in other cultures, or among younger or older individuals). Moreover, future studies assessing the RAS-1’s test-retest reliability in longitudinal designs and changes across cultural contexts will be beneficial for a more nuanced assessment of reliability and validity.

Conclusions

The findings of the present two-study investigation contribute to the growing body of literature regarding the associations between relationship satisfaction and other related constructs (e.g., Byers 2005; Stewart and Szymanski 2012; Hawkley et al. 2008) and the application of single-item measures in the social sciences (e.g., Cunny and Perri 1991; Dolan et al. 2015; Konrath et al. 2014; Konrath et al. 2018; Mark et al. 2013; Nagy 2002; Robins et al. 2001). The findings of the present studies indicate that the RAS-1 (a single-item measure of relationship satisfaction) is a valid and reliable tool to assess the level of relationship satisfaction, as suggested by its associations with the original RAS and theoretically relevant correlates. Thus, RAS-1 may be an appropriate measure of relationship satisfaction, particularly when researchers would like to apply a short, cost-effective measure of relationship satisfaction.

Acknowledgements: The research was supported by the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office (Grant numbers: KKP126835, and NKFIH-1157-8/2019-DT). BB was supported by the ÚNKP-18-3 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities and by a postdoctoral fellowship from the SCOUP Team – Sexuality and Couples – Fonds de recherche du Québec, Société et Culture. The funding agencies did not have input into the content of the manuscript and the views described in the manuscript reflect those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funding agencies.

References

Acker, M., & Davis, M. H. (1992). Intimacy, passion and commitment in adult romantic relationships: A test of the triangular theory of love. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9(1), 21–50.

Apt, C., Huribert, D. F., Pierce, A. P., & White, L. C. (1996). Relationship satisfaction, sexual characteristics and the psychosocial well-being of women. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 5(3), 195–210.

Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., & Orosz, G. (2015). Clarifying the links among online gaming, internet use, drinking motives, and online pornography use. Games for Health Journal, 4(2), 107–112.

Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2017). The pervasive role of sex mindset: Beliefs about the malleability of sexual life is linked to higher levels of relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction and lower levels of problematic pornography use. Personality and Individual Differences, 117, 15–22.

Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Zsila, Á., Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2018). The development of the problematic pornography consumption scale (PPCS). Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 395–406.

Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2020a). The short version of the problematic pornography consumption scale (PPCS-6): A reliable and valid measure in general and treatment-seeking populations. Journal of Sex Research, 1–11.

Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Potenza, M. N., Orosz, G., & Demetrovics, Z. (2020b). High-frequency pornography use may not always be problematic. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.01.007.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15(1), 141–154.

Byers, E. S. (2005). Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 42(2), 113–118.

Christophersen, T., & Konradt, U. (2011). Reliability, validity, and sensitivity of a single-item measure of online store usability. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 69(4), 269–280.

Cunny, K. A., & Perri III, M. (1991). Single-item vs multiple-item measures of health-related quality of life. Psychological Reports, 69(1), 127–130.

Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29.

Davison, S. L., Bell, R. J., LaChina, M., Holden, S. L., & Davis, S. R. (2009). The relationship between self-reported sexual satisfaction and general well-being in women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(10), 2690–2697.

de Jong-Gierveld, J. (1987). Developing and testing a model of loneliness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(1), 119–128.

de Jong-Gierveld, J. (1998). A review of loneliness: Concept and definitions, determinants and consequences. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 8(1), 73–80.

Dinkel, A., & Balck, F. (2006). An evaluation of the German relationship assessment scale. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 64, 259–263.

Dolan, E. D., Mohr, D., Lempa, M., Joos, S., Fihn, S. D., Nelson, K. M., & Helfrich, C. D. (2015). Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: A psychometric evaluation. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(5), 582–587.

Dolbier, C. L., Webster, J. A., McCalister, K. T., Mallon, M. W., & Steinhardt, M. A. (2005). Reliability and validity of a single-item measure of job satisfaction. American Journal of Health Promotion, 19(3), 194–198.

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412.

Dweck, C. (2012). Mindset: Changing the way you think to fulfil your potential (Updated ed.). London: Robinson.

Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C. Y., & Hong, Y. Y. (1995a). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A world from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267–285.

Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C. Y., & Hong, Y. Y. (1995b). Implicit theories: Elaboration and extension of the model. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 322–333.

Feeney, J. A. (2002). Attachment, marital interaction, and relationship satisfaction: A diary study. Personal Relationships, 9(1), 39–55.

Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In G. R. Hancock & R. D. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 269–314). Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

Fletcher, G. J. O., Simpson, J. A., & Thomas, G. (2000). The measurement of perceived relationship quality components: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(3), 340–354.

Fricker, J., & Moore, S. (2002). Relationship satisfaction: The role of love styles and attachment styles. Current Research in Social Psychology, 7(11), 182–205.

Gola, M., Lewczuk, K., & Skorko, M. (2016). What matters: Quantity or quality of pornography use? Psychological and behavioral factors of seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(5), 815–824.

Graham, J. M., Diebels, K. J., & Barnow, Z. B. (2011). The reliability of relationship satisfaction: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 39–48.

Grubbs, J. B., Sessoms, J., Wheeler, D. M., & Volk, F. (2010). The cyber-pornography use inventory: The development of a new assessment instrument. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 17(2), 106–126.

Gwinn, A. M., Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., & Maner, J. K. (2013). Pornography, relationship alternatives, and intimate extradyadic behavior. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(6), 699–704.

Hald, G. M., Træen, B., Noor, S. W., Iantaffi, A., Galos, D., & Rosser, B. S. (2015). Does sexually explicit media (SEM) affect me? Assessing first-person effects of SEM consumption among Norwegian men who have sex with men. Psychology & Sexuality, 6(1), 59–74.

Hawkley, L. C., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Masi, C. M., Thisted, R. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 63(1), 375–384.

Hendrick, S. S. (1988). A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family, 50(1), 93–98.

Hendrick, S. S., Dicke, A., & Hendrick, C. (1998). The relationship assessment scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(1), 137–142.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453.

Konrath, S., Meier, B. P., & Bushman, B. J. (2014). Development and validation of the single item narcissism scale (SINS). PLoS One, 9(8), e103469.

Konrath, S., Meier, B. P., & Bushman, B. J. (2018). Development and validation of the single item trait empathy scale (SITES). Journal of Research in Personality, 73, 111–122.

Lavner, J. A., & Bradbury, T. N. (2012). Why do even satisfied newlyweds eventually go on to divorce? Journal of Family Psychology, 26(1), 1–10.

Lee, J. A. (1973). The colors of love: An exploration of the ways of loving. Ontario: New Press.

Loo, R. (2002). A caveat on using single-item versus multiple-item scales. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17, 68–75.

Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Schutte, N. S., Bhullar, N., & Rooke, S. E. (2010). The five-factor model of personality and relationship satisfaction of intimate partners: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(1), 124–127.

Malouff, J. M., Schutte, N. S., & Thorsteinsson, E. B. (2014). Trait emotional intelligence and romantic relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Family Therapy, 42(1), 53–66.

Mark, K. P., Herbenick, D., Fortenberry, J. D., Sanders, S., & Reece, M. (2013). A psychometric comparison of three scales and a single-item measure to assess sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research, 51(2), 159–169.

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.-T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11, 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2.

Marsh, H. W., Ellis, L. A., Parada, R. H., Richards, G., & Heubeck, B. G. (2005). A short version of the self-description questionnaire II: Operationalizing criteria for short-form evaluation with new applications of confirmatory factor analyses. Psychological Assessment, 17(1), 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.17.1.81.

Martos, T., Sallay, V., Szabó, T., Lakatos, C., & Tóth-Vajna, R. (2014). Psychometric characteristics of the Hungarian version of the relationship assessment scale (RAS-H). Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika, 15(3), 245–258.

Maxwell, J. A., Muise, A., MacDonald, G., Day, L. C., Rosen, N. O., & Impett, E. A. (2017). How implicit theories of sexuality shape sexual and relationship well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(2), 238–279.

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

McKee, A. (2007). The relationship between attitudes towards women, consumption of pornography, and other demographic variables in a survey of 1,023 consumers of pornography. International Journal of Sexual Health, 19(1), 31–45.

Meeks, B. S., Hendrick, S. S., & Hendrick, C. (1998). Communication, love and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(6), 755–773.

Mellor, D., Stokes, M., Firth, L., Hayashi, Y., & Cummins, R. (2008). Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(3), 213–218.

Morin, A. J. S., Katrin Arens, A., & Marsh, H. W. (2015). A bifactor exploratory structural equation modeling framework for the identification of distinct sources of construct-relevant psychometric multidimensionality. Structural Equation Modeling, 23(1), 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.961800.

Muthén, B., & Kaplan, D. (1985). A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non-normal Likert variables. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 38(2), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1985.tb00832.x.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide. (7th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Nagy, M. S. (2002). Using a single-item approach to measure facet job satisfaction. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75(1), 77–86.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). In McGraw-Hill series in psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Orosz, G., Szekeres, Á., Kiss, Z. G., Farkas, P., & Roland-Lévy, C. (2015). Elevated romantic love and jealousy if relationship status is declared on Facebook. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 214.

Orosz, G., Tóth-Király, I., & Bőthe, B. (2016). Four facets of Facebook intensity—the development of the multidimensional Facebook intensity scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 100, 95–104.

Parade, S. H., Supple, A. J., & Helms, H. M. (2012). Parenting during childhood predicts relationship satisfaction in young adulthood: A prospective longitudinal perspective. Marriage & Family Review, 48, 150–169.

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Personal Relationships, 3, 31–56.

Pistole, M. C. (1989). Attachment in adult romantic relationships: Style of conflict resolution and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 6(4), 505–510.

Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jans, L. (2013). A single-item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 597–617.

Pyle, T., & Bridges, A. (2012). Perceptions of relationship satisfaction and addictive behavior: Comparing pornography and marijuana use. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1(4), 171–179.

Rask, M., Malm, D., Kristofferzon, M. L., Roxberg, Å., Svedberg, P., Arenhall, E., Baigi, A., Brunt, D., Fridlund, B., Ivarsson, B., Nilsson, U., Sjöström-Strand, A., Wieslander, I., & Benzein, E. (2010). Validity and reliability of a Swedish version of the relationship assessment scale (RAS): A pilot study. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 20(1), 16–21.

Renshaw, K. D., McKnight, P., Caska, C. M., & Blais, R. K. (2011). The utility of the relationship assessment scale in multiple types of relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28(4), 435–447.

Robins, R. W., Hendin, H. M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(2), 151–161.

Rogala, C., & Tydén, T. (2003). Does pornography influence young women’s sexual behavior? Women's Health Issues, 13(1), 39–43.

Rubin, Z. (1970). Measurement of romantic love. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 16(2), 265–273.

Rusbult, C. E., & Buunk, B. P. (1993). Commitment processes in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10(2), 175–204.

Sander, J., & Böcker, S. (1993). Die Deutsche Form der Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS): Eine kurze Skala zur Messung der Zufriedenheit in einer Partnerschaft. Diagnostica, 39(1), 55–62.

Schwartz, P., & Young, L. (2009). Sexual satisfaction in committed relationships. Sexuality Research & Social Policy, 6(1), 1–17.

Shrout, P. E., & Rodgers, J. L. (2018). Psychology, science, and knowledge construction: Broadening perspectives from the replication crisis. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1), 487–510. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011845.

Sprecher, S. (2002). Sexual satisfaction in premarital relationships: Associations with satisfaction, love, commitment, and stability. Journal of Sex Research, 39(3), 190–196.

Sternberg, R. J. (1997). Construct validation of a triangular love scale. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27, 313–335.

Stewart, D. N., & Szymanski, D. M. (2012). Young adult women’s reports of their male romantic partner’s pornography use as a correlate of their self-esteem, relationship quality, and sexual satisfaction. Sex Roles, 67(5–6), 257–271.

Szymanski, D. M., & Stewart-Richardson, D. N. (2014). Psychological, relational, and sexual correlates of pornography use on young adult heterosexual men in romantic relationships. Journal of Men's Studies, 22(1), 64–82.

Szymanski, D. M., Feltman, C. E., & Dunn, T. L. (2015). Male partners’ perceived pornography use and Women’s relational and psychological health: The roles of trust, attitudes, and investment. Sex Roles, 73(5–6), 187–199.

Vaillancourt-Morel, M. P., Daspe, M. È., Charbonneau-Lefebvre, V., Bosisio, M., & Bergeron, S. (2019). Pornography use in adult mixed-sex romantic relationships: Context and correlates. Current Sexual Health Reports, 11(1), 35–43.

Vaughn, M. J., & Matyastik Baier, M. E. (1999). Reliability and validity of the relationship assessment scale. American Journal of Family Therapy, 27(2), 137–147.

Voon, V., Mole, T. B., Banca, P., Porter, L., Morris, L., Mitchell, S., Lapa, T. R., Karr, J., Harrison, N. A., Potenza, M. N., & Irvine, M. (2014). Neural correlates of sexual Cue reactivity in individuals with and without compulsive sexual Behaviours. PLoS One, 9, e102419.

Wanous, J. P., & Hudy, M. J. (2001). Single-item reliability: A replication and extension. Organizational Research Methods, 4(4), 361–375.

Wanous, J. P., & Reichers, A. E. (1996). Estimating the reliability of a single-item measure. Psychological Reports, 78(2), 631–634.

Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Hudy, M. J. (1997). Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 247–252.

Willoughby, B. J., Carroll, J. S., Busby, D. M., & Brown, C. C. (2015). Differences in pornography use among couples: Associations with satisfaction, stability, and relationship processes. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 145–158.

Wright, P. J., Tokunaga, R. S., Kraus, A., & Klann, E. (2017). Pornography consumption and satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Human Communication Research, 43(3), 315–343.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The current study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Eötvös Loránd University (2015/359).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Flóra Fülöp and Beáta Bőthe contributed equally to this paper, they both should be considered first authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fülöp, F., Bőthe, B., Gál, É. et al. A two-study validation of a single-item measure of relationship satisfaction: RAS-1. Curr Psychol 41, 2109–2121 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00727-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00727-y