Abstract

In recent years, plentiful data has emerged indicating the detrimental effects of loneliness on well-being. One of the challenges for researchers dealing with this issue is to find the mechanism underlying the relationship. The present study investigated 293 adults, aged 19-40, and examined whether authenticity and rumination functioned as mediators in the relationship between loneliness and well-being (and its three domains – pleasure, engagement, and meaning). The results of the study confirmed the loneliness-well-being link and, additionally, revealed potential mechanisms explaining this relationship, which were of different character in the cases of the particular domains of well-being. As it turned out, authenticity was the sole significant mediator in the relationship between loneliness and meaning, and rumination played the role of key mediator between loneliness and pleasure. Both these mediators had their share in the indirect effects of loneliness on engagement and overall well-being. The relations revealed between loneliness and authenticity are, in turn, congruent with recent conceptualizations of authenticity, which emphasize the interpersonal sources of this variable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Loneliness, understood as subjectively felt discomfort in relation to unsatisfying personal relationships (Cacioppo and Patrick 2008), has powerful and detrimental effects on mental health. Previous research indicates that there are positive relationships between loneliness and depression (Cacioppo et al. 2010), hopelessness (Chang et al. 2010), suicidal ideation (Stravynski and Boyer 2001), psychological distress (Paul et al. 2006) and anxiety (Zawadzki et al. 2013). It has also been demonstrated that loneliness correlates negatively with well-being (Bramston et al. 2002; Golden et al. 2009) and its various indicators, e.g. life satisfaction (Akhunlar 2010), hedonic regulation (Yusoff et al. 2013) and meaning in life (Yeung and Fan 2013).

There is also data that points us in the direction of a relationship between loneliness and well-being. Longitudinal research has demonstrated that loneliness allows for the prediction of a lowered level of well-being (Vanderweele et al. 2012). Moreover, some experimental research has demonstrated that inducing feelings of loneliness decreases optimism (Cacioppo et al. 2006) and global perception of life as meaningful (Lambert et al. 2013; Stillman et al. 2009). The data mentioned above is in accord with the investigations made by some of the leading representatives of positive psychology, indicating the key relevance of healthy and intimate social relationships to an individual’s well-being (Diener and Seligman 2002; Baumeister 2005).

Little is still known about the mechanisms underlying the relationship between loneliness and well-being. However, some pieces of research and theories suggest that the key mechanisms mediating between loneliness and the various indicators of well-being should be sought in the different aspects of the self, whereas most researchers have focused primarily on self-esteem. For example, according to Leary (2005), self-esteem is a sociometer, an indicator of the individual’s current position in a group that detects all signs related to the risk of exclusion from the group, signaling them in the form of a negative affective response. Experimental research shows that loneliness and social rejection are linked to lowered self-esteem (Cacioppo et al. 2006; Zadro et al. 2004), while longitudinal studies demonstrate that self-esteem predicts well-being (Du et al. 2017). Finally, some studies have demonstrated directly that self-esteem mediates the relationship between loneliness and different indicators of well-being (Çivitci and Çivitci 2009; Yildiz and Karadas 2017). However, there are reasons to believe that the mediating mechanisms can be found not only in self-esteem but also in other features of the self, such as integrity and stability of self-knowledge or ways of processing self-relevant information. For example, previous studies on the negative aspects of mental health show that self-concept clarity mediates the relationship between social disconnection and depression (Richman et al. 2016). Ritchie et al. (2011) also demonstrated that self-concept clarity mediates the relationship between stress (one of the examined categories involved the situation linked to being socially rejected) and well-being. On the other hand, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies on private self-consciousness indicate that self-rumination, i.e. neurotic self-attentiveness, is a mediator in the relationship between loneliness and depression (Vanhalst et al. 2012; Zawadzki et al. 2013). In view of this data, the study under discussion here is an attempt to identify the explanatory mechanisms underlying the relationship between loneliness and well-being through referring to self-related variables other than self-esteem, i.e. authenticity and rumination. The presented study has three objectives. The first is to examine the mediating role of authenticity, a variable which combines the structural aspects of the self, processing of self-related information and self-expression, in the relationship between loneliness and well-being. Authenticity interpreted in this way is a well-established negative predictor of well-being (Boyraz et al. 2014) and, as shown by a recent study by Bryan et al. (2017) it negatively correlates with loneliness. The second objective is to see if rumination, as a type of self-awareness, which mediates the relationship between loneliness and depression, will play a similar role with reference to the positive aspects of well-being. The third is to define a potential, more complex mediation mechanism considering both authenticity and rumination.

Authenticity and Well-Being

One of the potential mediators of the relationship between loneliness and well-being may be authenticity, understood as the way of functioning in which one’s self is well-integrated and behavior is consistent with an individual’s beliefs and values (Kernis and Goldman 2006). According to Kernis and Goldman (2006), authenticity has four components: awareness, unbiased processing, authentic behavior and relational orientation. Awareness refers to being ready to continually explore and know one’s true feelings, desires, motives, and inclinations. Unbiased processing is related to processing incoming self-relevant information without cognitive distortions (e.g., defensiveness and self-serving biases). Authentic behavior refers to acting consistently in line with one’s values, interests, and needs. Relational orientation, on the other hand, refers to aiming for openness, sincerity, and honesty in interpersonal contacts, particularly in close relationships. Previous research has demonstrated that authenticity is positively associated with life satisfaction (Brunell et al. 2010) and subjective well-being (Wood et al. 2008). Interestingly, longitudinal studies indicate the unidirectional character of the relationship between authenticity and well-being. Authenticity predicts well-being but there is no reverse dependency (Boyraz et al. 2014).

Authenticity and Loneliness

So far only one study investigating the relationship between loneliness and authenticity indicated a negative correlation between the two variables (Bryan et al. 2017)Footnote 1. Additional, though indirect, evidence for the existence of the relationship between loneliness authenticity is provided by research which involves variables that are close in content to Kernis’ and Goldman’s theoretical construct. It turns out that loneliness is associated with variables which, similarly to the two components of authenticity (awareness and unbiased processing), connect to the clarity of self-knowledge and its integration - self-concept clarity and self-discrepancy. In the case of self-concept clarity, it is a negative correlation (Slotter et al. 2010) and in the case of self-discrepancy, it is positive (Gan and Chen 2017). The causal direction of the relationship between loneliness and accessibility, as well as clarity of the true self, may be indicated by data originating from both longitudinal and experimental studies. In the recently published longitudinal research by Richman et al. (2016), the negative relationship between loneliness and depression was shown to be mediated by self-concept confusion over time. Then again, experimental studies have revealed that an experience of being socially rejected increases self-uncertainty (Yavuz Güzel and Şahin 2018) and causes people to avoid self-awareness (Twenge et al. 2003). Considering all the data indicating that loneliness may reduce authenticity and that both variables are associated with well-being, it can be predicted that authenticity will mediate the relationship between loneliness and well-being.

The relationships Between Rumination and Loneliness and Well-Being

The research presented also set out to investigate whether rumination plays a mediating role in relationships between loneliness and well-being. According to Trapnell and Campbell (1999) rumination refers to self-focused attention, which implies the continuous analysis of situations linked with the sense of threat, loss or harm. The regulatory function of rumination consists in reducing the discrepancy between the current and desired state of the self, whereas numerous studies show that it paradoxically has the opposite effect (see Martin and Tesser 1996). As a result, people in whom this form of self-focused attention prevails, tend to experience sadness, anxiety, and anger. There are several arguments for the mediational role of rumination in the relationship between loneliness and well-being. Firstly, it has been demonstrated that the variable is correlated both with loneliness and well-being. Secondly, these relationships can be interpreted causally. It was revealed that experimentally induced loneliness led to increased rumination (Zwolinski 2011), whereas studies using a rumination-induction task demonstrated that this kind of cognitive activity lowered different indicators of psychological well-being (cf. Margolis and Lyubomirsky 2018). Thirdly, it has been demonstrated, in both cross-sectional and longitudinal research, that rumination is a mediator in the relationship between loneliness and depressive symptoms, which are referred to as negative aspects of well-being (Zawadzki et al. 2013).

Authenticity and Rumination

Both proposed mediators, i.e. authenticity and rumination, are mechanisms related within the self, as suggested by the cross-sectional study that revealed a negative correlation between them (Boyraz and Kuhl 2015). Looking at this relationship in causal categories, it might be concluded that it is authenticity which is a predictor of rumination rather than the other way round. First, according to Trapnell and Campbell (1999), rumination is usually induced by self-doubt and self-uncertainty. On the other hand, a very influential theory in developmental psychology suggests that uncertainty about one’s identity and the sense of being lost in defining the self, lead to ruminative explorations (Luyckx et al. 2008). Finally, in the experimental investigation by Gortner et al. (2006), it was shown that authentic self-expression led to reduced rumination. Therefore, it seems reasonable to suggest that authenticity contributes to lower rumination whereas inauthenticity leads to the intensification of ruminative thoughts.

The Current Study

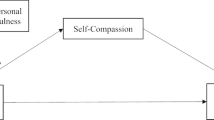

Considering the theoretical and empirical premises set out above, it was hypothesized that loneliness would be negatively associated with well-being (and all its domains) (H1) and that the relationship would be mediated by authenticity (H2) and rumination (H3) as mediators operating not only individually (separately) but also in a serial manner (H4) (see Fig. 1).

The hypothesized serial mediation model assumes that loneliness is associated with a lower level of authenticity which contributes to increased rumination, which in turn is associated with lower well-being and each of its domains.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The study was conducted in Poland on a group of 298 people residing in the Swietokrzyskie and Podkarpackie provinces. Having identified five multivariate outliers based on the Mahalanobis criterion, the statistical analysis included data from 293 people (194 women – 66.2%), aged 19-40 (M= 25.23, SD= 5.77). 191 (65.1%) people in our sample were educated to secondary level, including 180 who were students. 102 people (34%) were educated to degree level. The snowball sampling technique was adopted for the purpose of the study. Students, who comprised almost 61% of the whole sample, were invited to participate in the study by their lecturers. Additionally, each student was asked to recruit one adult. The respondents agreed to participate without any financial reward. All participants were briefed about the purpose of the study and gave their informed consent. The study was conducted in small groups by means of paper-and-pencil questionnaires. All of the required ethical standards were maintained.

Measures

Loneliness

The Loneliness Scale (De Jong-Gierveld and Kamphuis 1985), in the Polish adaptation by Grygiel et al. (2013), was used to measure general loneliness. The scale consists of 11 items. An example is: “I miss having really close friends.” The items are rated from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The Polish version of the instrument has satisfactory reliability and adequate construct validity (Grygiel et al. 2013). Cronbach’s alpha for the whole scale in the current study was 0.86. The Polish version of the tool correlates very highly with another popular measure of loneliness, i.e. the UCLA loneliness scale (Grygiel et al. 2013).

Authenticity

The Authenticity Inventory (Kernis and Goldman 2006), in the Polish adaptation by Kutnik (2014), was used to examine the sense of authenticity in everyday life. The assessment consists of 45 items (e.g., “I rarely, if ever, put on a ‘false face’ for others to see”) rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The Polish version of the instrument has previously demonstrated good reliability and validity (Kutnik 2014; Sobol-Kwapinska et al. 2016). Authenticity measured with this tool is highly correlated with self-concept clarity and identity integration (Kernis and Goldman 2006). Furthermore, the Polish version correlated moderately with mindfulness and highly with basic need satisfaction (Sobol-Kwapinska et al. 2016). The reliability of the four subscales ranged from 0.56 to 0.74 in the present study, with the full set of 45 items yielding an alpha of 0.84. Only the overall score was used in the analyses reported here.

Rumination

Rumination was measured with the 6-item Rumination subscale of the Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire Shortform (RRQ Shortforms; Trapnell 1997) in the Polish adaptation by Słowińska et al. (2014). The answering scale ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An example of a statement included in the scale: “Sometimes it is hard for me to shut off thoughts about myself”. In previous research, the reliability and validity of the tool were satisfactory (Słowińska et al. 2014). Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was 0.75.

Well-Being

The Steen Happiness Index (SHI) (Seligman et al. 2005), in the Polish adaptation by Kaczmarek et al. (2010), was used to measure the participants’ well-being. The scale consists of 20 items (including three buffer items) and requires participants to read a series of statements and pick the one that best describes how they felt in the previous week. The response alternatives range from a negative e.g. “I dislike my daily routine. Most of the time I am bored” to an extreme positive response e.g. “I enjoy my daily routine so much that I almost never take breaks from it”. Response choices range from 1 to 5. The theoretical basis of the tool is Seligman’s (2002) theory of authentic happiness and, in compliance with it, the items cover the subscales of pleasure (4 items, α = 0.66), engagement (7 items, α = 0.70) and meaning (6 items, α = 0.73) – the three pathways to happiness. These three factors are related but have their sources in different traditions of thinking about happiness. Pleasure refers to the hedonic well-being which involves increased positive affect, reduced negative affect, and high life satisfaction. Meaning definitely represents the eudaimonic tradition in thinking about happiness, whereas engagement is well expressed through Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) conceptualization of Flow (i.e. the psychological state that accompanies highly engaging activities) and is treated by researchers as an “amalgam” of hedonic and eudaimonic features (Peterson et al. 2005). The sum of items comprising the subscales is treated as the measure of overall well-being (17 items, α = 0.85), which in Seligman’s concept can be viewed as an indicator of full life, which combines the different paths to personal happiness (Seligman 2002). Kaczmarek et al. (2015) demonstrated that the tool is highly correlated with another popular measure of well-being, i.e. the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), both on the trait level, and on the occasion-specific level. This indicates that the SHI and the SWLS measure very similar constructs.

Data Analysis

The preliminary analyses included the determination of descriptive statistics of major variables and calculation of Pearson’s zero-order correlations as performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 21. The substantive serial mediation analysis included a bootstrap analysis employing the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013). More specifically, four separate serial mediation analyses were tested with reference to SHI total score and to SHI subscales (pleasure, engagement, meaning). In each of the mediation models the sex of the participants (1=male; 2=female), age and education were included as covariates and 10,000 bootstrap resamples were used to estimate the confidence intervals. When the 95% confidence intervals for an indirect effect did not include zero, the indirect effect was significant (MacKinnon et al. 2004). Additionally, AMOS 21 was used to calculate fit indices (AIC and ECVI) for comparing potentially competing models with different sequence of mediators.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Zero-Order Correlations

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alpha scores and correlations for the variables. The normality of the variables was supported as the absolute values of skewness and kurtosis were not greater than two (Gravetter and Wallnau 2014). As shown in Table 1, loneliness was positively correlated with rumination, and negatively correlated with authenticity and each of the well-being domains. Authenticity was, however, negatively correlated with rumination and positively correlated with well-being.

Serial Mediation Analyses

In the next step, the serial mediation models with authenticity and rumination as mediators of the link between loneliness and well-being outcomes were tested (see Tables 2 and 3).

The first serial mediation analysis tested for whether rumination and authenticity would mediate the relationship between loneliness and overall well-being (see Table 2). The results showed that overall well-being was negatively predicted by loneliness, ß = -0.24, p < 0.001 and rumination (ß = -0.10, p < 0.05), and positively predicted by authenticity (ß = 0.19, p < 0.05). Age and sex as covariates were not specifically linked to the output variable but participants with a higher education declared a marginally higher level of well-being than those with a secondary education, ß = 0.06, p < 0.01. The analysis showed the significance of three indirect effects. Both rumination and authenticity were found to independently mediate the association between loneliness and general well-being, B = -0.04, SE = 0.02, 95 % CI = [-0.084, -0.007] for authenticity; B = -0.01, SE = 0.01, 95 % CI = [-0.037, -0.001] for rumination. It was also found that loneliness inhibited well-being through lowering authenticity, which in turn was linked with higher rumination (i.e., serial mediation effect), B = - 0.01, SE = 0.001, 95 % CI = [-0.025, -0.003]. The serial mediation model, as described, explained 22.7% of the variance of general well-being, F(6,286) = 13.98, p < 0.001.

The next analogous serial mediation analyses were performed for particular domains of well-being as output variables (i.e. pleasure, engagement and meaning, see Table 3).

In the domain of pleasure, the results indicated that pleasure was negatively predicted by loneliness, ß = -0.24, p < 0.001 and rumination, ß = -0.15, p < 0.01. Authenticity was not specifically linked to pleasure, similarly to age and sex, which were not related to pleasure at all. The participants with higher education declared higher levels of pleasure than those with secondary education, ß = 0.10, p < 0.05. Two of the indirect effects tested were proven to be significant, with rumination playing a significant role in both. In the first case, which took the form of single mediation, loneliness inhibited pleasure through increasing rumination, B = -0.02, SE = 0.01, 95 % CI = [-0.050, -0.002]. In the second case, the linkage also considered the role of authenticity. Loneliness inhibited pleasure through lowering authenticity and then through increasing rumination (i.e. serial mediation effect), B = -0.02, SE = 0.01, 95 % CI = [-0.034, -0.006]. The model explained 16.9 % of the variance of pleasure, F(6,286) = 9.68, p < 0.001.

In regard to engagement as the output variable, loneliness, ß = -0.21, p < 0.001 and rumination, ß = -0.10, p < 0.05 turned out to be negatively predictive of this domain of well-being whereas authenticity turned out to be its positive predictor, ß = 0.21, p < 0.05. None of the covariates was specifically linked to engagement. The analysis showed the significance of three indirect effects. Both rumination and authenticity were found to independently mediate the association between loneliness and engagement, B = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95 % CI = [-0.095, -0.005] for authenticity; B = -0.01, SE = 0.01, 95 % CI = [-0.040, -0.001] for rumination. It was also found that loneliness inhibited engagement through lowering authenticity and then through increasing rumination (i.e. serial mediation effect), B = -0.01, SE = 0.01, 95 % CI = [-0.027, -0.003]. The discussed serial mediation model explained 18.3% of the variance of engagement, F(6.286) = 10.66, p < 0.001.

The last serial mediation analysis was performed for meaning as a domain of well-being. The results showed that meaning was negatively predicted by loneliness, ß = -0.26, p < 0.001 and positively by authenticity, ß = 0.30, p < 0.01. Rumination, as well as age and education as covariates, were not specifically related to meaning, but women reported a marginally lower level of meaning than men, ß = -0.12, p < 0.1. Only one of the tested indirect effects was proven to be significant - loneliness inhibited meaning through lowering authenticity, B = -0.07, SE = 0.03, 95 % CI = [-0.123, -0.021]. The discussed serial mediation model explained 18.6% of the variance of meaning, F(6.286) = 10.36, p < 0.001.

Testing the Alternative Model

Because theoretically, it is also possible that loneliness increases rumination, which in turn contributes to lower authenticity (cf. Boyraz and Kuhl 2015), an additional alternative model with the opposite sequence of mediators was tested. It was analogous to the original model, but rumination was replaced by authenticity and vice versa. Within a set of models for the same data, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike 1974) and Expected Cross Validation Index (ECVI; Browne and Cudeck 1993) can be used to compare the competing models that need not be nested (the smaller the better). For the original model, the AIC and ECVI values were 68.10 and 0.23 respectively in the case of overall well-being score as output variable, and 88.34 and 0.30 respectively in the cases of 3 distinct domains of well-being as output variables. By comparison, for the alternative model the AIC and ECVI values were 99.61 and 0.34 respectively in the case of overall well-being, and 119.27 and 0.41 for the three domains of well-being. The values of AIC and ECVI suggested that that original model with authenticity as antecedent of rumination is better suited to data than the alternative model with the opposite sequence of mediators.

Discussion

The aim of the research presented in this paper was to define the relationship between loneliness and well-being, taking into account the mediating role of authenticity and rumination. The results confirmed the findings of the previous research which showed a detrimental effect of loneliness on well-being. Loneliness turned out to be a significant negative predictor of each aspect of well-being included in the study, i.e. pleasure, engagement and meaning. What is more, the results of mediation analyses cast new light on potential mechanisms that might explain the relationship between loneliness and well-being. Three types of mediation effects have been revealed, with authenticity and rumination as separate single mediators and with these variables as serial mediators.

The mediation effect of rumination corresponds with the results of research which showed that the variable mediates in the relationship between loneliness and depressive symptoms (Vanhalst et al. 2012). A similar situation obtains in the case of overall well-being as well as pleasure and engagement; loneliness intensifies the level of rumination, which in effect reduces the level of well-being in the areas under consideration. Furthermore, it turned out that rumination as a mediator takes part in a more complex chain of relationships involving authenticity. These serial mediation effects indicate that loneliness reduces authenticity thus intensifying rumination, which is associated with the lowering of overall well-being, pleasure, and engagement. These results suggest that the impact of loneliness on rumination may, at least partly, be the effect of a difficult contact with the true self. The intensification of rumination may be interpreted as the consequence of processes of self-reflection aimed at redefining one’s self and reducing self-discrepancies (cf. Martin and Tesser 1996). Remarkably, in the present study ruminative cognitive activity did not show a relationship with perceiving life in terms of meaning and consequently did not mediate the relationship between loneliness and this variable. It should be noted, however, that the result reflects the unequivocal character of the relationship between rumination and the meaning of life as suggested by some authors, as rumination correlates negatively with the presence of meaning in life and positively with searching for the meaning of life (Steger et al. 2008; Newman and Nezlek 2019). Rumination, therefore, might not necessarily make it more difficult to perceive life in terms of sense; what’s more, according to Martin and Tesser (1996), thinking again and again about difficult experiences might constitute an important process of attributing meaning to them.

It turned out that the role of the sole mediator in the relationship between loneliness and meaning is played by authenticity. Moreover, authenticity both separately and serially, along with rumination, mediates the relationship between loneliness and engagement, and between loneliness and overall well-being. The results suggest that satisfactory relationships with others, especially with significant others, are a key to the validation of the true self, which consequently translates to well-being. This thesis is consistent both with the classic theoretical concepts indicating the social sources of self (Mead 1934; Wallace and Tice 2012), contemporary concepts of authenticity (Wang 2016; Schmader and Sedikides 2017) and the results of studies that demonstrate that feeling socially disconnected predicts a low level of self-concept clarity (Ayduk et al. 2009; Slotter et al. 2010; Richman et al. 2016). Lowered authenticity as an effect of loneliness may be explained by the accompanying social rejection or exclusion, the mechanisms related to psychological defense. As Twenge et al. (2003) demonstrated in their experimental studies, people avoid self-awareness in situations of social rejection, which the authors think may be a mechanism for defending the self against focused attention on socially undesirable traits. Slightly different self-protective mechanisms are described in the evolutionary model of loneliness, according to which in the situation of being socially disconnected the self-preservation mode is activated, characterized by higher sensitivity to any potential social threats and excessive concentration on the self (Cacioppo et al. 2006). The activation of these defensive tendencies is connected to numerous cognitive biases, including those concerning oneself (for example higher self-criticism). At the neurobiological level, this may be linked with a reduced activity of the temporal parietal junction (TPJ), responsible for creating representations of the self and of others relevant to the situation (Boehme et al. 2015). In the context of authenticity, a defensive approach excludes the possibility of unbiased processing of self-related information, lowers one’s readiness to self-disclosure and general openness towards others. This has been confirmed by the results of previous research which demonstrates that authenticity is negatively associated with defensiveness with reference to self-relevant information (Lakey et al. 2008). Lower authenticity may also result from cognitive and motivational contradictions within the self, appearing as the consequence of experiencing loneliness. Firstly, loneliness can be considered as a perceived discrepancy between the actual and ideal social self (Kupersmidt et al. 1999), whereas this type of self-discrepancy is linked with lower authenticity (Gan and Chen 2017). Secondly, according to Cacioppo and collaborators (Cacioppo et al. 2014; Cacioppo and Hawkley 2009), loneliness activates competitive motivational tendencies – to avoid social threats on the one hand, and to re-establish one’s relationship with the social environment on the other. The first is linked to the recalling of information in respect of previous interpersonal failure, the second is related to the necessity to introduce the necessary amendments to one’s social functioning in order to avoid loneliness in the future. In practice, both tendencies mean that it is necessary to verify one’s assumptions about the self and adapt one’s behavior to the perceived demands and expectations of others (c.f. Snyder and Gangestad 2000), which may, in turn, lead to lower authenticity (Schmader and Sedikides 2017).

In addition to this, the analysis that took into consideration the various aspects of well-being demonstrated that in the case of pleasure, rumination was a significant mediator both as a single mediator and through authenticity, which corresponded with the results of research showing that rumination was a mediator in the relationship between loneliness and depressive symptoms (Vanhalst et al. 2012). It can therefore be concluded that this variable is a regulator of hedonic well-being (related to affective balance). In the case of meaning, on the other hand, the mediating role is played only by authenticity, which confirms that the variable is strongly related to eudaimonic rather than hedonic well-being (Smallenbroek et al. 2017).

The present findings should be interpreted in the light of several limitations. First, as the present study was cross-sectional, causality cannot be inferred. The proposed models partly rely on experimental and longitudinal data, but the directions of the proposed causal relationships should become subject to further detailed, particularly experimental, research. The second limitation is that the data for this study was obtained from self-reporting scales. In addition, the fact that most of the participants were female limits the generalizability of the findings.

Despite the limitations noted, the current study makes a useful contribution to the theory and research on the relationship between loneliness and well-being and indicates other potential explanatory mechanisms among self-related variables. When considering the directions for future research in this area, apart from the testing of the mediating relationships in the experimental studies, it would also be reasonable to include self-esteem and the variables related to the organizational and dynamic aspect of the self simultaneously, so as to be able to see which of those variables provide a better explanation for the relationship between loneliness and well-being. It would be also interesting to see if the effect of loneliness on authenticity is moderated by rejection sensitivity or independent versus interdependent self-construal.

Notes

It should also be considered that Bryan et al. (2017) used another method for measuring loneliness, seeing authenticity in the role of moderator rather than mediator of the relationship between loneliness and mental health, and also alcohol-related problems. In the current study, no hypothesis was proposed regarding the potential moderating role of authenticity because the author became familiar with Baker et al.’s work at the stage of already working on the results of his own study. However, additional analyses were carried out, which demonstrated that in the present study authenticity did not moderate the relationship between loneliness and well-being. The results are available directly from the author of the current study.

References

Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 19, 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705.

Akhunlar, M. N. (2010). An investigation about the relationship between life satisfaction and loneliness of nursing students ın Uşak University. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 2409–2415. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SBSPRO.2010.07.472.

Ayduk, Ö., Gyurak, A., & Luerssen, A. (2009). Rejection sensitivity moderates the impact of rejection on self-concept clarity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(11), 1467–1478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209343969.

Baumeister, R. F. (2005). The cultural animal: Human nature, meaning, and social life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boehme, S., Miltner, W. H. R., & Straube, T. (2015). Neural correlates of self-focused attention in social anxiety. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 10(6), 856–862. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsu128.

Boyraz, G., & Kuhl, M. L. (2015). Self-focused attention, authenticity, and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 87, 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.029.

Boyraz, G., Waits, J. B., & Felix, V. A. (2014). Authenticity, life satisfaction, and distress: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(3), 498–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000031.

Bramston, P., Pretty, G., & Chipuer, H. (2002). Unravelling subjective quality of life: An investigation of individual and community determinants. Social Indicator Research, 59, 261–274.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park: Sage.

Brunell, A. B., Kernis, M. H., Goldman, B. M., Heppner, W., Davis, P., Cascio, E. V., & Webster, G. D. (2010). Dispositional authenticity and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 900–905.

Bryan, J. L., Baker, Z. G., & Tou, R. Y. (2017). Prevent the blue, be true to you: Authenticity buffers the negative impact of loneliness on alcohol-related problems, physical symptoms, and depressive and anxiety symptoms. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(5), 605–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315609090.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. New York: Norton.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Ernst, J. M., Burleson, M., Berntson, G. G., Nouriani, B., & Spiegel, D. (2006). Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(6), 1054–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.007.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017216.

Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., & Boomsma, D. I. (2014). Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cognition & Emotion, 28, 3–21.

Chang, E. C., Sanna, L. J., Hirsch, J. K., & Jeglic, E. L. (2010). Loneliness and negative life events as predictors of hopelessness and suicidal behaviors in hispanics: evidence for a diathesis-stress model. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(12), 1242–1253. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20721.

Çivitci, N., & Çivitci, A. (2009). Self-esteem as mediator and moderator of the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 954–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.022.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper and Row.

De Jong-Gierveld, J., & Kamphuis, F. (1985). The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 9, 289–299.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00415.

Du, H., King, R. B., & Chi, P. (2017). Self-esteem and subjective well-being revisited: The roles of personal, relational, and collective self-esteem. PLOS ONE, 12(8), e0183958. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183958.

Gan, M., & Chen, S. (2017). Being Your Actual or Ideal Self? What It Means to Feel Authentic in a Relationship. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(4), 465–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216688211.

Golden, J., Conroy, R. M., Bruce, I., Denihan, A., Greene, E., Kirby, M., & Lawlor, B. A. (2009). Loneliness, social support networks, mood and wellbeing in community-dwelling elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(7), 694–700. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2181.

Gortner, E. M., Rude, S. S., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2006). Benefits of Expressive Writing in Lowering Rumination and Depressive Symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 37(3), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.01.004.

Gravetter, F., & Wallnau, L. (2014). Essentials of statistics for the behavioral sciences (8th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth.

Grygiel, P., Humenny, G., Rebisz, S., Świtaj, P., & Sikorska, J. (2013). Validating the Polish adaptation of the 11-item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 29(2), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000130.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: The Guilford Press.

Kaczmarek, L. D., Stanko-Kaczmarek, M., & Dombrowski, S. (2010). Adaptation and validation of the Steen Happiness Index into Polish. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 3, 98–104.

Kaczmarek, L. D., Bujacz, A., & Eid, M. (2015). Comparative latent state–trait analysis of satisfaction with life measures: The Steen Happiness Index and the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(2), 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9517-4.

Kernis, M. H., & Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. In M. P. Zanna & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 38, pp. 283–357). San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38006-9.

Kupersmidt, J., Sigda, K., Sedikides, C., & Voegler, M. (1999). Social self-discrepancy theory and loneliness during childhood and adolescence. In K. Rotenberg & S. Hymel (Eds.), Loneliness in childhood and adolescence (pp. 263–279). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511551888.013.

Kutnik, J. (2014). Autentyczność - psychologiczna analiza zjawiska na podstawie teorii egzystencjalnej. [Authenticity – psychological analysis on the basis of existential theory] (Unpublished Master’s Thesis). Lublin: Catholic University of Lublin.

Lakey, C. E., Kernis, M. H., Heppner, W. L., & Lance, C. E. (2008). Individual differences in authenticity and mindfulness as predictors of verbal defensiveness. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 230–238.

Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F., & Fincham, F. D. (2013). To belong is to matter: sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213499186.

Leary, M. R. (2005). Sociometer theory and the pursuit of relational value: getting to the root of self-esteem. European Review of Social Psychology, 16, 75–111.

Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Berzonsky, M. D., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Smits, I., & Goossens, L. (2008). Capturing ruminative exploration: Extending the four-dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 58–82.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128.

Margolis, S., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2018). Cognitive outlooks and well-being. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being (pp. 143–158). Salt Lake City: DEF Publishers nobascholar.com.

Martin, L. L., & Tesser, A. (1996). Some ruminative thoughts. In R. S. Wyer (Ed.), Ruminative thoughts: Advances in social cognition (Vol. 9, pp. 1–47). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Newman, D. B., & Nezlek, J. B. (2019). Private self-consciousness in daily life: Relationships between rumination and reflection and well-being, and meaning in daily life. Personality and Individual Differences, 136, 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2017.06.039.

Paul, C., Ayis, S., & Ebrahim, S. (2006). Psychological distress, loneliness and disability in old age. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 11(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500500262945.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z.

Richman, S. B., Pond, R. S., Dewall, C. N., Kumashiro, M., Slotter, E. B., & Luchies, L. B. (2016). An unclear self leads to poor mental health: Self-concept confusion mediates the association of loneliness with depression. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 35(7), 525–550. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2016.35.7.525.

Ritchie, T. D., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Arndt, J., & Gidron, Y. (2011). Self-concept clarity mediates the relation between stress and subjective well-being. Self and Identity, 10(4), 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2010.493066.

Schmader, T., & Sedikides, C. (2017). State authenticity as fit to environment: The implications of social identity for fit, authenticity, and self-segregation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(3), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868317734080.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress. Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60, 410–421.

Slotter, E. B., Gardner, W. L., & Finkel, E. J. (2010). Who am I without you? The influence of romantic breakup on the self-concept. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209352250.

Słowińska, A., Zbieg, A., & Oleszkowicz, A. (2014). Kwestionariusz Ruminacji-Refleksji (RRQ) Paula D. Trapnella i Jennifer D. Campbell – polska adaptacja metody [Paul D. Trapnell and Jennifer D. Campbell’s Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ) – polish adaptation of the measure]. Polskie Forum Psychologiczne, 19, 457–478.

Smallenbroek, O., Zelenski, J. M., & Whelan, D. C. (2017). Authenticity as a eudaimonic construct: The relationships among authenticity, values, and valence. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12, 197–209.

Snyder, M., & Gangestad, S. (2000). Self-monitoring: Appraisal and reappraisal. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 530–555. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.126.4.530.

Sobol-Kwapinska, M., Jankowski, T., & Przepiorka, A. (2016). What do we gain by adding time perspective to mindfulness? Carpe Diem and mindfulness in a temporal framework. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.07.046

Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., Sullivan, B. A., & Lorentz, D. (2008). Understanding the search for meaning in life: personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76, 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x.

Stillman, T. F., Baumeister, R. F., Lambert, N. M., Crescioni, A. W., DeWall, C. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). Alone and without meaning: Life loses meaning following social exclusion. Journal of Experimental and Social Psychology, 45, 686–694.

Stravynski, A., & Boyer, R. (2001). Loneliness in relation to suicide ideation and parasuicide: a population-wide study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 31(1), 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.31.1.32.21312.

Trapnell, P.D. (1997). RRQ shortforms. Retrieved September 10, 2018, from http://www.paultrapnell.com/ measures/RRQshortforms.rtf

Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 284–304.

Twenge, J. M., Catanese, K. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2003). Social exclusion and the deconstructed state: time perception, meaninglessness, lethargy, lack of emotion, and self-awareness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(3), 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.409.

Vanderweele, T. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). On the reciprocal association between loneliness and subjective well-being. American Journal of Epidemiology, 176(9), 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws173.

Vanhalst, J., Luyckx, K., Raes, F., & Goossens, L. (2012). Loneliness and depressive symptoms: The mediating and moderating role of uncontrollable ruminative thoughts. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 146(1–2), 259–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.555433.

Wallace, H. M., & Tice, D. M. (2012). Reflected appraisal through a 21st-century looking glass. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (Vol. 2, pp. 124–140). New York: Guilford.

Wang, Y. N. (2016). Balanced authenticity predicts optimal well-being: Theoretical conceptualization and empirical development of the authenticity in relationships scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.001.

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the authenticity scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.385.

Yavuz Güzel, H., & Şahin, D. (2018). The effect of ostracism on the accessibility of uncertainty-related thoughts. Arch Neuropsychiatry, 55, 183–188. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2017.19342.

Yeung, J. K., & Fan, C. S. (2013). Being socially isolated is a matter of subjectivity: The mediator of life meaning and moderator of religiosity. Revista De Cercetare Si Interventie Sociala, 42, 204–227.

Yildiz, M. A., & Karadas, C. (2017). Multiple mediation of self-esteem and perceived social support in the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(3), 130–139.

Yusoff, N., Luhmann, M., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2013). Explaining the link between loneliness and self-rated health with hedonic regulation as a mediator. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 97, 156–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.216.

Zadro, L., Williams, K. D., & Richardson, R. (2004). How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower mood and self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 560–567.

Zawadzki, M. J., Graham, J. E., & Gerin, W. (2013). Rumination and anxiety mediate the effect of loneliness on depressed mood and sleep quality in college students. Health Psychology, 32(2), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029007.

Zwolinski, J. (2011). Psychological and Neuroendocrine Reactivity to Ostracism. Aggressive Behavior, 38(2), 108–125.

Acknowledgments

The author declares no actual or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within 3 years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence, their work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The procedure performed in this study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This manuscript has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Borawski, D. Authenticity and rumination mediate the relationship between loneliness and well-being. Curr Psychol 40, 4663–4672 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00412-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00412-9