Abstract

Remembering on past emotional episodes frequently elicits an affective state in the remembering person, and remembering in a social context is usually accompanied by narration. This study considers the relationship between the narrator’s affective state and the structure of narratives. More specifically, the study addressees the question whether the temporal structure of narratives reveals the intensity of narrators’ current affective state. The study included 75 participants. They were asked to recount past emotion episodes applying a cue word paradigm with the following emotion category labels: anger, sadness, joy, and pride. Intensity of the narrators’ current affective state was assessed by physiological and self-report measures. The temporal structure of narratives was reflected by the two features of specific temporal reference and temporal unfolding. These features were coded by the method of automated linguistic analysis. The results show that specific temporal reference reflects affective intensity measured as the level of arousal while temporal unfolding reflects affective intensity measured as the valence of the narrator’s current affective state. Results are discussed by highlighting the function of temporal structure of narratives in reliving past experiences during narration.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Beukeboom, C. J., & Semin, G. R. (2006). How mood turns on language. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42, 553–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.09.005.

Bohanek, J. G., Fivush, R., & Walker, E. (2005). Memories of positive and negative emotional events. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 19, 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1064.

Conway, M. A. (2001). Sensory–perceptual episodic memory and its context: Autobiographical memory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B., 356(1413), 1375–1384. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2001.0940.

Costello, A. M., Bruder, G. A., Hoenfeld, C., & Dunchan, J. F. (1995). A structural analysis of a fictional narrative: “A free night”. In J. F. Duchan, G. A. Bruder, & L. E. Hewitt (Eds.), Deixis in narrative. A cognitive science perspective (pp. 461–485). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cowie, R., McKeown, G., & Douglas-Cowie, E. (2012). Tracing emotion: An overview. International Journal of Synthetic Emotions, 3(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.4018/jse.2012010101.

Forgas, J. P. (2014). Feeling and speaking: Affective influences on communication strategies and language use. In J. P. Forgas, O. Vincze, & J. László (Eds.), Social cognition and communication. Sydney symposium of social psychology (pp. 63–81). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Frijda, N. (2007). The Laws of emotions. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gobbo, C., & Raccanello, D. (2007). How children narrate happy and sad events: Does affective state count? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21, 1173–1190. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1324.

Gray, E. K., & Watson, D. (2007). Assessing positive and negative affect via self-report. In J. A. Coan, & J J. B. Allen (Eds.), Handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment. (pp. 171–183). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gottschalk, L. A., & Bechtel, R. J. (2008). Computerized Content Analysis of Speech and Verbal Texts and its Many Applications. New York: Nova Science Publisher.

Habermas, T., Ott, L. M., Schubert, M., Schneider, B., & Pate, A. (2008). Stuck in the past: Negative bias, explanatory style, temporal order, and evaluative perspective in life narratives of clinically depressed individuals. Depression and Anxiety, 25(11), 1091–4269. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20389.

Herman, D. (2002). Story Logic: Problems and Possibilities of Narrative. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Hoeken, H., & van Vliet, M. (2000). Suspense, curiosity, and surprise: How discourse structure influences the affective and cognitive processing of a story. Poetics, 27(4), 277–286 SSDI 0304-422X(94)00007-S.

Hudson, J. A., Gebelt, J., Haviland, J., & Bentivegna, C. (1992). Emotion and narrative structure in young children’s personal accounts. Journal of Narrative and Life History, 2(2), 129–150.

Kunda, Z. (1999). Social Cognition. In Making sense of people. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Labov, W., & Waletzky, J. (1967). Narrative analysis: Oral versions of personal experience. In J. Helms (Ed.), Essays on the verbal and visual arts (pp. 4–44). Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Levine, L. J. (1997). Reconstructing memory for emotions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 126(2), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.126.2.165.

Nelson, K. L., & Horowitz, L. M. (2001). Narrative structure in recounted sad memories. Discourse Processes, 31(3), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326950dp31-3_5.

Oatley, K. (1999). Why fiction may be twice as true as fact: Fiction as cognitive and emotional simulation. Review of General Psychology, 3(2), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.3.2.101.

Pasupathi, M. (2003). Emotion regulation during social remembering: Differences between emotions elicited during an event and emotions elicited when talking about it. Memory, 11(2), 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/741938212.

Pillemer, D. B. (1998). Momentous events, vivid memories. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pillemer, D. B., Desrochers, A., & Ebanks, C. (1998). Remembering the past in the present: Verb tense shifts in autobiographical memory narratives. In C. P. Thompson, D. J. Herrmann, D. Bruce, J. D. Read, D. G. Payne, & M. P. Toglia (Eds.), Autobiographical memory: Theoretical and applied perspectives (pp. 148–162). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Polanyi, L. (1985). Conversational storytelling. In T. A. van Dijk (Ed.), Handbook of Discourse Analysis (Vol. Vol. 3, pp. 183–201). Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Pólya, T., & Gábor, K. (2010). Linguistic structure, narrative structure and emotional intensity. Third International Workshop on Emotion, Corpora for Research on Emotion and Affect. (pp. 20–24.). LREC, Valetta.

Posner, J., Russell, J. A., & Peterson, B. S. (2005). The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 17(3), 715–734. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579405050340.

Raes, F., Hermans, D., Decker, A. D., Eelen, P., & Williams, J. M. G. (2003). Autobiographical memory specificity and affect regulation: An experimental approach. Emotion, 3(2), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.3.2.201.

Ravaja, N. (2004). Contributions of psychophysiology to media research: Review and recommendations. Media Psychology, 6, 193–235. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0602_4.

Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1161–1178.

Russell, J. A., Lewicka, M., & Niit, T. (1989a). A cross-cultural study of a circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 848–856. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.848.

Russell, J. A., Weiss, A., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (1989b). Affect Grid: A single-item scale of pleasure and arousal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(3), 493–502. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.493.

Strapparava, C., & Mihalcea, R. (2015). Affect detection in texts. In: R. A. Calvo, S. K. D'Mello, J. Gratch, & A. Kappas, (Eds). The Oxford handbook of affective computing. (pp. 184–203). New York, NY, Oxford University Press.

Sze, J. A., Gyurak, A., Yuan, J. W., & Levenson, R. W. (2010). Coherence between emotional experience and physiology: Does body awareness training have an impact? Emotion, 10(6), 803–814. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020146.

Toolan, M. J. (2001). Narrative. A critical linguistic introduction (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Wennerstrom, A. (2001). Intonation and evaluation in oral narratives. Journal of Pragmatics. 33, 1183–1206. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(00)00061-8.

Williams, J. M. G. (1996). Depression and the specificity of autobiographical memory. In D. C. Rubin (Ed.), Remembering our past. Studies in autobiographical memory (pp. 244–267). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Wood, W. J., & Conway, M. (2006). Subjective impact, meaning making, and current and recalled emotions for self-defining memories. Journal of Personality, 74(3), 811–845. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00393.x.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Tilmann Habermas, János László, and James Pennebaker for their helpful comments on the draft version of this paper.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office – NKFIH (grant number K 124206) and by the Bolyai Research Scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Tibor Pólya declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1. The affect grid: Source: Gray & Watson 2007 p: 180-181

Subjects have to check the appropriate cell of the grid to describe their affective state in the following way. The cell at the center position of the grid represents a neutral, average, everyday affective state. Moving upward from the center position, the cells represent emotional arousal states increasing from the average to the extreme, while cells below the center are for affective states below average in arousal. Similarly, cells to the right of the center position represent positive emotions, and cells to the left stand for negative emotions. In this way, the selection of one cell represents both the level of arousal and the valence of the affective state.

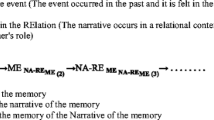

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pólya, T. Temporal structure of narratives reveals the intensity of the narrator’s current affective state. Curr Psychol 40, 281–291 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9921-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9921-8