Abstract

The purpose of this article is to map research literature on intergenerational contact in refugee and international migration contexts. Using database searches on Scopus, Medline, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Education Research Complete, we identified 649 potentially relevant studies, of which 134 met the inclusion criteria and are mapped in the article by themes, date of publication, geographical distribution, study design, and targeted population. The review has been developed with input from migrant and refugee charities, and it identifies research trends in the field as well as multiple gaps in the literature. The results highlight the complex ways in which intergenerational contact impacts psycho-social wellbeing and integration, health, and education outcomes for both refugees and other migrant groups. Much of the research to date has focused on relationships within families. Studies exploring the potential tensions and benefits of intergenerational contact between refugees/migrants and members of the broader community are lacking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Throughout the migration journey, refugees and asylum seekers face a variety of challenges, amongst them the often-forced separation from families, older relatives, and other loved ones (Dubow & Kuschminder, 2022). Extensive research has shown that family separation has adverse effects on refugees’ mental health and wellbeing (Liddell et al., 2022; Löbel, 2020; Miller et al., 2018), alongside other known risk factors such as pre-migration trauma and post-migration stress (Chen et al., 2017; Fazel et al., 2012). Even where families migrate together, they face unique challenges as each member of the family adjusts to the destination context at their own pace and in line with their own beliefs and aspirations.

The social contacts and relationships which emerge between refugees and members of the receiving society have also been extensively researched in the context of refugee, migration, and integration studies (recently for instance by Huysmans et al., 2021; Phillimore, 2021; Sellars, 2022), but seldom from an intergenerational perspective. Similarly, in their interventions, service delivery and training to staff, refugee support organisations often plan for potential language and cultural barriers, however intergenerational communication barriers and pitfalls and their intersection with culture, as well as the benefits of intergenerational learning for both refugees and locals, are often overlooked. The primary aim of this mapping review is therefore to identify, systematically describe and organise the evidence currently available from empirical research on intergenerational contact in refugee settlement contexts. We approach this field from a comparative perspective, drawing on data and insights from both refugee-specific studies as well as the existing body of evidence on the intergenerational contacts that people from migration background sustain with family, acquaintances, and members of the community beyond the borders of their country of origin.

In the context of this mapping review, intergenerational contact refers to any contact between older and younger individuals, be they family or unrelated individuals. We will primarily consider studies that have explored ways in which intergenerational contact influences either social attitudes and values (with regard to care, education, consumption, gender norms, transmission of intangible cultural heritage, political participation, etc.) or the integration-, health- and wellbeing outcomes of migrant and refugee populations, or both. Studies assessing how the second- or third-generation migrants fare in terms of socioeconomic outcomes such as wealth or social class compared to the first-generation migrants and native populations, without providing insights into interpersonal and social relationships across two or more generations, will not be discussed. This topic has been extensively covered elsewhere (e.g., Agius Vallejo & Keister, 2020).

The questions guiding this mapping review are as follows:

-

Q1: What is the state-of-the-art in research on intergenerational contact in refugee and international migration contexts?

-

Q2: What are the main themes and topics investigated in connection to people in refugee-like situations as compared to other migrant groupsFootnote 1 in the intergenerational (contact) literature?

-

Q3: What are the key gaps that should direct future research in this field?

Method

Systematic Mapping Review

A systematic mapping review provides the means to broadly map an area of research and to produce a range of descriptive data to highlight temporal, geographical, and thematic trends. Employing established methodological approaches from systematic reviews, mapping reviews are effective in uncovering research gaps, pinpointing areas with substantial evidence, and laying the groundwork for meta-analysis and meta-synthesis (Essex et al., 2022; Soaita et al., 2020). The comprehensive overview generated by this mapping review will serve as a valuable resource for migration scholars who wish to enter the field of intergenerational research as well as for those aiming to deepen their understanding of intergenerational dynamics in migration contexts. Additionally, the review will aid researchers and practitioners in swiftly navigating the existing literature landscape, identifying pivotal studies, and fostering potential interdisciplinary collaborations.

Search Strategy

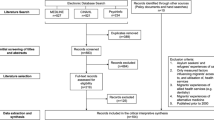

To identify relevant literature, five databases (Scopus, Medline, CINAHL, PsycInfo and Education Research Complete) were searched from inception to 22 February 2022. The key search terms within titles, keywords and abstracts were intergenerational or multi-generational and migration or migrant or immigrant or refugee or forced migrant or asylum seeker. These search terms were combined with concepts and terms referring to community focussed initiatives. Table S1 of the Supplement A shows the complete search strategy used on Scopus. After removing duplicates (n = 176), 473 records were retained for eligibility assessment. The screening and study selection process has been documented using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021) (see Fig. 1).

Eligibility Criteria

Peer-reviewed articles reporting on quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies involving refugees, asylum applicants, or first-, second-, or third generation migrants as participants were considered eligible. The study aims and outcomes had to be related to intergenerational contact and/or the article had to report on interventions, activities or contexts which involved individuals belonging to at least two different age cohorts where one or more cohorts were from migration background. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: wrong population (e.g., research with non-migrants, internally displaced people, returnees, or participants in rural–urban migration within the same country), wrong aim (studies without an intergenerational component or contact between two age groups), wrong design (reviews, commentaries, books, letters, dissertations, perspective pieces or articles not reporting empirical data) or where full-text was not available.

Screening Process

The first level of screening was completed using Rayyan QCRI (https://www.rayyan.ai/), a web-based reference manager system for collaborative reviews. Titles and abstracts were screened independently against the eligibility criteriaFootnote 2; disagreements and references marked as undecided (n = 93) were resolved by discussion involving a third assessor. Studies that were considered potentially relevant were moved to the next stage during which the review team assessed 223 full-text articles and identified 134 studies for inclusion.Footnote 3

Stakeholder Workshop

We held a stakeholder engagement workshop on June 7th, 2022, with the participation of five refugee and migrant charities from London and Southeast England.Footnote 4 During the workshop, early observations from the review were discussed to identify potential topics, questions and comparisons for further exploration based on the screened body of literature.Footnote 5

Data Extraction and Coding

The data extraction form was developed by the review team and piloted on ten eligible studies. The data extraction was completed by four researchers with a random 25 percent also assessed independently by the lead author. There was 85 percent or higher agreement for each data extractor. The following data were extracted: background information (author, country, year), study design and method used, sample (size, age and other demographics, country of origin, type of migration and migrant groups involved), and the main outcomes assessed. Following data extraction, the studies were further coded and categorised according to the age groups involved and the main topics researched in relation to intergenerational contact (e.g., intergenerational conflict, family cohesion, acculturation, care, transmission of trauma, psychological problems, and educational expectations). The final list of categories for data extraction and coding, which was established in line with our preliminary results and the input collected during the stakeholder workshop, is shown in Table S2 of Supplement A.

Data Analysis

The data extracted from the studies were first analysed using descriptive statistics with temporal and geographical data represented in visual graphs to illustrate trends. Next, we explored the distribution of studies by population (refugees vs non-refugees) and context and ranked the main themes investigated. Spearman’s correlation assessments were also conducted to explore whether a connection exists between the themes. Correlation tests are common in review articles as they seek to explore whether a relationship exists between two dichotomous variables. The coefficients are then used to indicate the direction and strength of the relationship.

Results

Descriptive Results

Our searches yielded 649 references, of which 134 studies met the inclusion criteria. The number of papers published per year (Fig. 2) suggests a substantive growth of interest in the topic over the past decades, with 35 studies published in the period from 2000 to 2009, 70 publications in 2010–2020, and a further 26 studies already published since 2020. The majority of these studies were carried out in the United States (n = 72), followed by Australia (n = 19), Canada (n = 10) and the United Kingdom (n = 6). The geographical distribution of the remaining studies is shown in Fig. 3.

Distribution of studies by year of publication (The studies published since January 2022 to date have not been included in Fig. 1.)

The examined studies included participants of various age groups. Amongst the papers that reported this data, when only one group was included in the study the mean age of participants was 34 years, with a range of 10–75 years. When a comparison was made between a younger and older group, the mean age of the younger group was 18 years, with a range of 1–47 years, whilst the mean age of the older group was 44 years, with a range of 12–75 years. Around 37 percent of the reviewed literature discussed intergenerational contact or relationships involving people in refugee-like situation, mostly individuals who or whose family members fled from Eastern and South-Eastern Asia (e.g., Vietnam, Cambodia, and Myanmar) and Sub-Saharan Africa. Likewise, the most common region of origin for the other migrant groups studied was Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, along with Latin America and the Caribbean, and Central and Southern Asia (Fig. 4). As to different generations of immigrants involved in intergenerational research, the studies to date have mainly focussed on the views and experiences of first (settled) and second-generation migrants (Fig. 5). Much less attention has been paid to the role of intergenerational contact in the lives of newly arrived international migrants, those recently seeking asylum or living in refugee camps or those navigating complex transnational relationships. Similarly, the majority of studies have scrutinised intergenerational contact inside the family, although research has also been expanding into nonfamilial relationships between older and younger people (Fig. 6). Only a few studies in this latter group (n = 5), however, engaged people from both migrant and non-migrant backgrounds.

Distribution of studies by the research participants’ region of origin and status. ESEA: Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, SSA: Sub-Saharan Africa, NAWA: Northern Africa and Western Asia, LAC: Latin America and the Caribbean, CSA: Central and Southern Asia, EUR: Europe, UNK: unknown, MULTI: multiple (two or more of the aforementioned regions) (Our classification of countries into regions of origin was guided by the UN International Migration report (https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Feb/un_2019_internationalmigration_wallchart.pdf))

The principal analytical perspectives which informed the studies making up the corpus included cultural identity and acculturation (exploring how different generations navigate and adapt to a new environment), psychosocial wellbeing (investigating psychological and emotional effects as well as coping mechanism), social integration and networks, generational power dynamics and gender studies (exploring gender roles, caring responsibilities and power structures within families), communication, and education, social work and healthcare perspectives. From a methodological perspective, the reviewed studies relied primarily on qualitative data (53 percent, mostly obtained from interviews and focus groups with one or more age cohorts); 40 percent used a quantitative approach (34 cross-sectional studies, 17 studies with cohort- or similar longitudinal study design and six intervention studies) and a further 7 percent reported mixed methods studies (Fig. 7). No temporal trend in the employed methods was apparent.

Themes

The most common themes in the mapped literature—for both studies involving people in refugee-like situations and those conducted with other migrant groups—are acculturation and conflict. The latter have been described as arising from different levels of adjustment to the destination context by children and their parents/caretakers, and it has been discussed in the literature under multiple labels, amongst them, intergenerational cultural conflict (Chung, 2006; Y. Li, 2014; Mwanri et al., 2018; Wu & Chao, 2005), intergenerational acculturation gap (Lim et al., 2009; Merali, 2004; Renzaho et al., 2017; Y.-W. Ying & Han, 2007a, 2007b, 2007c), intergenerational cultural dissonance (Choi et al., 2008; Kane et al., 2016), generation gap and assimilation disparity (Merali, 2002). In the refugee-specific literature, other common topics included psychological problems (e.g., depression, alcohol and drug abuse, anxiety, distress and suicidal ideation) which often accompanied intergenerational conflicts within families (Kane et al., 2016; Mwanri et al., 2018; Ying & Han, 2007a, b, c, 2008b) and/or were considered the result of the intergenerational transmission of (pre)migration trauma and war/conflict exposure (Back Nielsen et al., 2019; Bager et al., 2020; East et al., 2018; Hoffman et al., 2020; Mak et al., 2021; Rizkalla et al., 2020; Sangalang et al., 2017; Sim et al., 2018).

Another overarching theme that we have identified in the refugee-specific literature is communication, which has been studied in relation to intergenerational conflicts and broader parent–child relational contextsFootnote 6 (Atwell et al., 2009; Greenfield et al., 2020; McCleary et al., 2020; Mulholland et al., 2021), acculturation (Merali, 2005), trauma (Krahn, 2013; Lin et al., 2009; Sangalang et al., 2017) and trust and disclosure (Bermudez et al., 2018; Douglass et al., 2021). Family cohesion (Ayika et al., 2018; Tippens, 2020; Ying & Han, 2007a), care for relatives and parenting (including parental control and uses of physical discipline practices in families with migration background) have been other themes explored in the refugee-specific literature, with the latter ones, care and parenting, being mainly investigated in tandem with the effects of trauma and war exposure (Anakwenze & Rasmussen, 2021; Cho Kim et al., 2019; Sim et al., 2018), acculturation and heritage culture (Hatoss, 2022; Tajima & Harachi, 2010; Tsai et al., 2017), sexual and reproductive health (Dean et al., 2017), and gender expectations (Kallis et al., 2020; Mulholland et al., 2021). Post-migration stressors (Atwell et al., 2009; McCleary et al., 2020; Rizkalla et al., 2020; Sim et al., 2018), social exclusion and life on the margins of society (Douglass et al., 2021; East et al., 2018; Mavhandu-Mudzusi, 2019; Mwanri et al., 2018) and the negative impact of these on intergenerational relationships, and inter alia on acculturation, health and wellbeing outcomes for different generations of migrants have also been investigated in the refugee-specific literature, although to a lesser extent than the other themes listed earlier. A complete list of themes is provided in Table 1 which also shows the frequency distribution for research involving people in refugee-like situation versus research conducted with other migrant groups. Table 2 ranks the themes according to their frequency in the refugee-specific literature and shows the result of the theme correlation analysis.

Results for the correlation coefficientsFootnote 7 show Acculturation and heritage culture is positively correlated with Conflict at 0.3454 and Other lifestyles at 0.2850. A negative coefficient is found with (Pre-)migration trauma at -0.4353 and with Health at − 0.2955.Footnote 8 Interestingly, (Pre-)migration trauma is also negatively correlated with Conflict at − 0.2976 but is positively correlated with Psychological problems at 0.2894 and Other negative outcomes at 0.2976. Health is also positively correlated with Psychological problems at 0.3056. Gender is positively correlated with Sexual and reproductive health at 0.4772. As expected, Education is positively correlated with Skills development at 0.4845.

Intergenerational conflicts stemming from different levels of parent–child acculturation were also a major focus for research conducted with other populations from migration-background, that is those who did not identify as refugees and/or were not labelled as such by researchers (Choi et al., 2008; Chung, 2006; Goitom, 2018; J. Li, 2009; Li, 2014; Lim et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2017; Phinney et al., 2000). The topic of intergenerational (acculturation) conflict in this segment of the literature has mainly emerged in studies also concerned with parenting dynamics (Deepak, 2005; Lim et al., 2009; Marcus et al., 2019; Wu & Chao, 2005), care for relatives (Li et al., 2019; Tezcan, 2018), and mental health problems in older/younger generations such as depression, anxiety and alcohol abuse (Hwang et al., 2010; Li, 2014; Lim et al., 2009; Nguyen et al., 2018; Park, 2003; Weaver & Kim, 2008; Yasui et al., 2018; Ying & Han, 2007b, 2008a). Certain themes—e.g., family cohesion (Flores, 2018; Garcia et al., 2013; Howes et al., 2011; Kao & An, 2012; Merz et al., 2009; Willgerodt & Thompson, 2005), care particularly for older relatives (Amin & Ingman, 2014; Flores, 2018; Guo et al., 2019; Kalavar et al., 2020; Lai, 2007; Laidlaw et al., 2010; Mao et al., 2018; Spira & Wall, 2009; Sudha, 2014) and education (Blanchet-Cohen & Reilly, 2017; Ginn et al., 2018; Herzig van Wees et al., 2021; Mendez, 2015; Sime & Pietka-Nykaza, 2015; Warburton & McLaughlin, 2007)—were far more prominent in intergenerational research involving (other) migrant groups than in the refugee-specific literature. The ranked list of all themes in this second group along with the correlation analysis is shown in Table 3.

Results show a negative correlation between Acculturation and heritage culture and Skills development at − 0.2835. Conflict showed the highest number of coefficients that are statistically significant. A positive correlation was found between Conflict and Family cohesion at 0.2634, Parenting at 0.2504, Psychological problems at 0.3153 and Other negative outcomes at 0.3249. A negative coefficient was also found between Conflict and Care for relatives at − 02650. Family cohesion and Other negative outcomes shows a positive result at 0.2388. Care for relatives showed two negative results with studies on Parenting at -0.2712 and Communication at − 0.25. This indicates an increase in Care for relatives results to a decline in both variables. Communication and (Pre-)migration trauma showed a positive outcome at 0.35. Church and religious spaces showed three positive outcomes with Health at 0.2354, Political participation at 0.2907, and Other lifestyle at 0.3318. Other lifestyle positively correlated with Food, nutrition, and obesity at 0.2582. All mentioned results are statistically significant at a p value < 0.05.

Discussion: Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Avenues

Overall, the reviewed literature suggests that intergenerational contact in refugee settlement contexts is a small but growing field of research. The majority of publication included in this review have been published in the last fifteen years and they have focused primarily on intergenerational contact between related individuals. By comparison, very little was found in the literature about intergenerational contact which emerge between individuals in refugee-like situation (or migrants in general) and members of the broader community. Research from non-migration contexts introduce reasons for both optimism and pessimism concerning intergenerational relationships outside family contexts. Several lines of evidence (North & Fiske, 2012) point to potential tensions stemming from prescriptive stereotypes, ageism, and intergenerational competition over societal resources (e.g., work, housing, and government benefits), all of which are likely to be amplified if the contact involves immigrants, amongst them refugees, who continue to be perceived by parts of the society as a treat and/or drain on scarce national resources (Klein, 2021; Onraet et al., 2021). At the same time, research from across different fields has also shown that strong, consistent relationship between old(er) and young(er) generations can debunk intergroup prejudice and stereotypes, reduce isolation, contribute to subjective wellbeing, and improve economic, educational, as well as societal participation (Bryer, 2019; Hunter et al., 2018; Kahlbaugh & Budnick, 2021; North & Fiske, 2012). Much of the current literature is focussed on the negatives (conflict, mental health problems and to a lesser extent problematic and antisocial behaviour), whilst studies delving into the potential benefits of intergenerational contact for refugee populations are largely missing.

The reviewed literature has highlighted the complex and multifaced ways in which intergenerational relationships—particularly within refugee-background families—impact younger generation’s psycho-social wellbeing and outcomes. There is also an extent literature dedicated to the intergenerational transmission of trauma and the effects of pre-migration experiences on parenting and children’s mental health outcomes. Furthermore, an important part of the literature also focuses on the exploration of the dynamics and consequences of intergenerational conflicts stemming from different levels of adjustment to the context of reception. The majority of these intergenerational conflict studies—in both the refugee-specific and broader migrant literature—attempted to classify research participants and their children/parents as high or low on receiving-culture acquisition and on heritage-culture retention in line with earlier conceptualisations of acculturation (Schwartz et al., 2010), which however also meant that the context of settlement, along with the extent of social exclusion, discrimination and other post-migration stressors that older/younger generations of migrants possibly experienced were often not considered.

Beyond tracing the above discussed themes in the current refugee-specific and broader migration literature, the review has also pinpointed new areas of inquiry for strengthening the practical and policy-value of intergenerational research with refugee populations. These included major public health concerns (e.g., childhood overweight and obesity (Halliday et al., 2014; Vue et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2010; Zulfiqar et al., 2021), and sexual and reproductive health and rights (Alcalde & Quelopana, 2013; Dean et al., 2017; Mulholland et al., 2021; Rogers & Earnest, 2014; Herzig van Wees et al., 2021; Villani & Bodenmann, 2017), as well as other themes of significance—for instance, education (Blanchet-Cohen & Reilly, 2017; Mendez, 2015; Singh et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2022), skills exchange and development (Ginn et al., 2018; Hébert et al., 2020; Leek, 2021; Leek & Rojek, 2021) and political participation and belonging (Bloemraad & Trost, 2008; Reynolds et al., 2018; Terriquez & Kwon, 2015)—which have been extensively studied in relation to migrant populations, but are still under-explored from an intergenerational perspective, particularly when it comes to the challenges and benefits of intergenerational contact outside family contexts (North & Fiske, 2012). The few studies that did connect unrelated individuals were almost exclusively set in educational contexts and focussed on a narrow set of skills (e.g., literacy and digital skills) rather than on positive social interactions and relationship-building between the younger and older in community settings. The nature of this latter process, and how and why it does (not) occur, should be a priority for future research. Considering the breadth of the reviewed literature, studies applying a gender lens and/or recounting gendered experiencesFootnote 9 have also been scarce.

When looking more closely at the type of the research conducted, this varied substantially in terms of research participants, aims, methods and as shown above themes. The breadth of methodologies utilised by researchers was widespread and the studies managed to recruit participants from different ethnic minorities (amongst them refugees from all major conflict areas in the past fifteen years), age-cohorts and migrant generations, which is encouraging. There were however relatively few studies involving new arrivals. There is also a lack of translational research and/or co-production involving practitioners, community organisations and/or individuals with lived experience (with some notable exceptions: e.g., Reynolds et al., 2018). As public involvement in research is being strengthened and systematically embedded through institutional policies and funding regulations, future research into intergenerational contacts will need to involve practitioners, community organisations, and representatives of different age cohorts from amongst refugee (migrant) populations and other members of the public in determining research questions and priorities, ethics, and implementation.

As to the broader implications of this review, feedback from charities/associationsFootnote 10 representing sub-groups of refugee and migrant populations in Southeast England confirmed the role of generations working together in improving social cohesions and understanding between communities. Delegates from these stakeholder organisations have also seen a great value in tackling some of the major societal and public health concerns involving refugee populations from an intergenerational perspective, amongst them those highlighted in this discussion earlier (psycho-social wellbeing, tackling isolation and discrimination, and educational success). A research priority for this group of stakeholders is the identification of different delivery models and good practice guidelines for the integration of intergenerational work in their day-to-day activities to ensure young and older people equally engage with and benefit from their support services as well as their broader interventions aimed at creating social connections between refugees, their families, and members of the receiving community.

With the above in mind, we suggest the following directions for future research:

-

Development of interdisciplinary and practitioner-oriented research topics in collaboration with community organisations, practitioners, and people with lived experience

-

More empirical research focused on compounding factors such as gender, race, and the context of settlement in the investigation of intergenerational contact and its effects

-

More empirical research focused on the impact of intergenerational programmes and other support activities connecting refugees with members of the broader community

-

Investigation into the enablers and barriers to such programmes and their benefits for psycho-social wellbeing, intergenerational learning, and family and community cohesion

The above should also be accompanied with the documentation of practical lessons that could feed into future guidance for setting up intergenerational programmes involving individuals in refugee-like situation and/or other migrants.

Conclusion

The aim of this article was to review intergenerational research involving refugees and other migrant groups to map the themes addressed and identify directions for future research. The review looked at a large body of material (data extracted from 134 publications), which varied substantially in terms of research participants, aims, topics and methods used. The mapping has provided an overview of major themes and the relationships between them, which provides an important first step in delineating what is already known to provide a strong basis for further exploration.

The increasing focus on intergenerational research within migration studies reflects a recognition of the profound impact that such research can have on understanding the (re)settlement and integration experiences of migrant and refugee communities. The review allows migration scholars to situate their work within the broader landscape of intergenerational research, and it offers a reference point for them to identify gaps in knowledge, emerging trends, and areas that warrant further exploration. Beyond academia, non-academic stakeholders, including practitioners, non-governmental organisations and charities dedicated to supporting migrants, can also derive substantial benefits from this work. It serves as both a resource and an overview of pivotal studies, equipping these stakeholders with insights that can inform their advocacy efforts and interventions, ultimately contributing to an enhancement in the quality of life for refugee and migrant communities. To our knowledge, this is one of the few systematic mapping reviews in refugee studies, and the first one to include stakeholder consultation and input, which add further value to the study. We have also identified several key directions for future research and practice; it is hoped these will allow for capitalising on the opportunities for exchange, learning and mutual support brought by successful intergenerational programmes and the integration of intergenerational work in refugee support organisations day-to-day activities.

There are also some limitations that warrant consideration, most notably the exclusion of grey literature along with the geographical distribution of the reviewed studies. Grey literature often encapsulates valuable insights from various stakeholders, and neglecting this type of information may result in overlooking community-driven perspectives on intergenerational relationships. The stakeholder engagement workshop that we conducted partially mitigated the impact of this by harnessing the diverse experiences and knowledge of local migrant and refugee charities. Likewise, the workshop provided an opportunity for dialogue and collaboration on the suggested research agenda, ensuring that it resonates with the community’s concerns and priorities.

The geographical distribution of the reviewed studies also raises concerns about the generalisability of the findings. This is skewed towards English-speaking countries, with the overwhelming majority of publications coming from just four countries (United States, Australia, Canada, and United Kingdom). This Western-centric bias limits for instance the applicability of the proposed research agenda to a more global context, given that significant refugee populations and diverse migration experiences exist in regions where English is not the primary language of research and academic publishing. A comprehensive multilingual search strategy would have been more inclusive, enabling a more extensive representation of global research on intergenerational contact in contexts related to refugees and international migration. Going forward, a more nuanced examination is needed to understand how the suggested research agenda might require adjustments or expansions to encompass diverse regional, cultural, and linguistic settings.

Notes

The notions of “refugee” and “international migrant” are complex and multifaceted, subject to varying interpretations influenced by political, social, and disciplinary perspectives. In this review, we adhere to the categorisations employed by the authors of the original studies, where refugees are generally considered as individuals fleeing persecution or violence, and international migrants as those who move across borders primarily for purposes such as education, employment, or family reunification.

Titles and abstracts were screened by EK and RH; full text articles were assessed by EK, RH, EH and MM.

The complete list of assessed studies (including reasons for exclusion) and the full data extraction table underpinning the manuscript are available from the corresponding author on request.

Lewisham Refugee and Migrant Network, Diversity House, Somali Integration and Development Association, Metro, and Medway Plus.

Topics and questions examined during the workshop included: How do different generations within refugee/migrant communities perceive and experience intergenerational contact? In what ways do (cultural) differences within families/communities affect intergenerational relationships? How do traditional parental/carer roles and expectations evolve in the context of migration? How does intergenerational contact contribute to (or hinder) the integration of refugee and migrant families? How can education and community programmes better facilitate positive interactions between different age groups? What community-based initiatives have been successful in promoting positive intergenerational relationships?

For example, family separation and reunification, parental control, and communication about sexuality.

A higher positive correlation coefficient represents a greater increase in co-occurrence of themes. A lower positive coefficient suggests a tendency for such themes to occur less frequently together.

In the context of co-occurrence of themes, a higher negative correlation coefficient implies that an increase in the expression of one variable (theme) correlates with a decrease in the other.

See Stakeholder workshop in the “Method” section.

References

Agius Vallejo, J., & Keister, L. A. (2020). Immigrants and wealth attainment: Migration, inequality, and integration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(18), 3745–3761. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1592872

Alcalde, M. C., & Quelopana, A. M. (2013). Latin American immigrant women and intergenerational sex education. Sex Education, 13(3), 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2012.737775

Amin, I., & Ingman, S. (2014). Eldercare in the transnational setting: Insights from Bangladeshi transnational families in the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 29(3), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-014-9236-7

Anakwenze, O., & Rasmussen, A. (2021). The impact of parental trauma, parenting difficulty, and planned family separation on the behavioral health of West African immigrant children in New York City. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(4), 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra000101

Atwell, R., Gifford S. M., & McDonald-Wilmsen B. (2009). Resettled refugee families and their children’s futures: Coherence, hope and support. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 40 (5): 677–97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41604320

Ayika, D., Dune, T., Firdaus, R., & Mapedzahama, V. (2018). A qualitative exploration of post-migration family dynamics and intergenerational relationships. SAGE Open, 8(4), 215824401881175. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018811752

Back Nielsen, M., Carlsson, J., Køster Rimvall, M., Petersen, J. H., & Norredam, M. (2019). Risk of childhood psychiatric disorders in children of refugee parents with post-traumatic stress disorder: A nationwide, register-based, cohort study. The Lancet Public Health, 4(7), e353–e359. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30077-5

Bager, L., Agerbo, E., Skipper, N., Høgh Thøgersen, M., & Laursen, T. M. (2020). Risk of psychiatric diagnoses in children and adolescents of parents with torture trauma and war trauma. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142(4), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13203

Bermudez, L. G., Parks, L., Meyer, S. R., Muhorakeye, L., & Stark, L. (2018). Safety, trust, and disclosure: A qualitative examination of violence against refugee adolescents in Kiziba camp, Rwanda. Social Science and Medicine, 200, 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.018

Blanchet-Cohen, N., & Reilly, R. C. (2017). Immigrant children promoting environmental care: Enhancing learning, agency and integration through culturally-responsive environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 23(4), 553–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1153046

Bloemraad, I., & Trost, C. (2008). It’s a family affair: Intergenerational mobilization in the spring 2006 protests. American Behavioral Scientist, 52(4), 507–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276420832460

Brotman, S., Silverman, M., Boska, H., & Molgat, M. (2021). Intergenerational care in the context of migration: A feminist intersectional life-course exploration of racialized young adult women’s narratives of care. Affilia, 36(4), 552–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109920954408

Bryer, N. (2019). Review of key mechanisms in intergenerational practices, and their effectiveness at reducing loneliness/social isolation. Social Research and Information Division. Welsh Government. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2019-05/review-key-mechanisms-intergenerational-practices-their-effectiveness-reducing-loneliness-social-isolation.pdf

Chen, W., Hall, B. J., Ling, L., & Renzaho, A. M. N. (2017). Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: Findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30032-9

Cho Kim, S., Manchester, C., & Lewis, A. (2019). Post-war immigration experiences of survivors of the Korean war. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 28(8), 977–995. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1392388

Choi, Y., He, M., & Harachi, T. W. (2008). Intergenerational cultural dissonance, parent-child conflict and bonding, and youth problem behaviors among Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9217-z

Chung, I. W. (2006). A cultural perspective on emotions and behavior: An empathic pathway to examine intergenerational conflicts in Chinese immigrant families. Families in Society, 87(3), 367–376. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3541

Dean, J., Mitchell, M., Stewart, D., & Debattista, J. (2017). Intergenerational variation in sexual health attitudes and beliefs among Sudanese refugee communities in Australia. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 19(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2016.1184316

Deepak, A. C. (2005). Parenting and the process of migration: Possibilities within South Asian families. Child Welfare, 84(5), 585–606.

Douglass, C. H., Block, K., Horyniak, D., Hellard, M. E., & Lim, M. S. C. (2021). Addressing alcohol and other drug use among young people from migrant and ethnic minority backgrounds: Perspectives of service providers in Melbourne, Australia. Health and Social Care in the Community, 29(6), e308–e317. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13355

Dubow, T., & Kuschminder, K. (2022). Family strategies in refugee journeys to Europe. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(4), 4262–4278. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feab018

East, P. L., Gahagan, S., & Al-Delaimy, W. K. (2018). The impact of refugee mothers’ trauma, posttraumatic stress, and depression on their children’s adjustment. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(2), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0624-2

Essex, R., Weldon, S. M., Markowski, M., Gurnett, P., Slee, R., Cleaver, K., Stiell, M., & Jagodzinski, L. (2022). A systematic mapping literature review of ethics in healthcare simulation and its methodological feasibility. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 73, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2022.07.001

Fazel, M., Reed, R. V., Panter-Brick, C., & Stein, A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: Risk and protective factors. The Lancet, 379(9812), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60051-2

Flores, A. (2018). The descendant bargain: Latina youth remaking kinship and generation through educational Sibcare in Nashville Tennessee. American Anthropologist, 120(3), 474–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13052

Garcia, C. M., Aguilera-Guzman, S., Lindgren, R., Gutierrez, B., Raniolo, T., Genis, G., Vazquez-Benitez, & Clausen L., (2013). Intergenerational photovoice projects: Optimizing this mechanism for influencing health promotion policies and strengthening relationships. Health Promotion Practice, 14 (5): 695–705. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26740586

Ginn, C. S., Benzies, K. M., Keown, L. A., Raffin Bouchal, S., & Thurston, W. E. (2018). Stepping stones to resiliency following a community-based two-generation Canadian preschool programme. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(3), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12522

Goitom, M. (2018). ‘Bridging several worlds’: The process of identity development of second-generation Ethiopian and Eritrean young women in Canada. Clinical Social Work Journal, 46(3), 236–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-017-0620-y

Greenfield, P. M., Espinoza, G., Monterroza-Brugger, M., Ruedas-Gracia, N., & Manago, A. M. (2020). Long-term parent-child separation through serial migration: Effects of a post-reunion intervention. School Community Journal, 30(1), 267–298.

Guo, M., Kim, S., & Dong, X. (2019). Sense of filial obligation and caregiving burdens among Chinese immigrants in the United States. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67, S564–S570. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15735

Halliday, J. A., Green, J., Mellor, D., Mutowo, M. P., de Courten, M., & Renzaho, A. M. N. (2014). Developing programs for African families, by African families: Engaging African migrant families in Melbourne in health promotion interventions. Family and Community Health, 37(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000011

Hatoss, A. (2022). That word ‘abuse’ is a big problem for us: South Sudanese parents’ positioning and agency vis-à-vis parenting conflicts in Australia. Linguistics and Education 67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2021.101002

Hébert, C., Thumlert, K., & Jenson, J. (2020). #Digital parents: Intergenerational learning through a digital literacy workshop. Journal of Research on Technology in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2020.1809034

Herzig van Wees, S., Fried, S., & Larsson, E. C. (2021). Arabic speaking migrant parents’ perceptions of sex education in Sweden: A qualitative study. Sexual & Reproductive HealthCare 28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100596

Hoffman, S. J., Vukovich, M. M., Gewirtz, A. H., Fulkerson, J. A., Robertson, C. L., & Gaugler, J. E. (2020). Mechanisms explaining the relationship between maternal torture exposure and youth adjustment in resettled refugees: A pilot examination of generational trauma through moderated mediation. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 22(6), 1232–1239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01052-z

Howes, C., Vu, J. A., & Hamilton, C. (2011). Mother-child attachment representation and relationships over time in Mexican-heritage families. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 25(3), 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2011.579863

Hunter, K., Wilson, A., & McArthur, K. (2018). The role of intergenerational relationships in challenging educational inequality: Improving participation of working-class pupils in higher education. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 16(1–2), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2018.1404382

Huysmans, M., Lambotte, D., Muls, J., Vanhee, J., Meurs, P., & Verté, D. (2021). Young newcomers’ convoy of social relations: The supportive network of accompanied refugee minors in urban Belgium. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(3), 3221–3244. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa130

Hwang, W.-C., Wood, J. J., & Fujimoto, K. (2010). Acculturative family distancing (AFD) and depression in Chinese American families. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(5), 655–667. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020542

Kahlbaugh, P., & Budnick, C. J. (2021). Benefits of intergenerational contact: Ageism, subjective well-being, and psychosocial developmental strengths of wisdom and identity. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development., 96, 135. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914150211050881

Kalavar, J. M., Zarit, S. H., Lecnar, C., & Magda, K. (2020). I’m here, you’re there: In-absentia caregiver stress and transnational support of elderly mothers by adult children. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 320–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2020.1787044

Kallis, G., Yarwood, R., & Tyrrell, N. (2020). Gender, spatiality and motherhood: Intergenerational change in Greek-Cypriot migrant families in the UK. Social and Cultural Geography, 23(5), 697–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2020.1806345

Kane, J. C., Johnson, R. M., Robinson, C., Jernigan, D. H., Harachi, T. W., & Bass, J. K. (2016). The impact of intergenerational cultural dissonance on alcohol use among Vietnamese and Cambodian adolescents in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(2), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.002

Kao, H. F. S., & An, K. (2012). Effect of acculturation and mutuality on family loyalty among Mexican American caregivers of elders. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 44(2), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01442.x

Klein, G. R. (2021). Refugees, perceived threat and domestic terrorism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2021.1995940.

Krahn, E. (2013). Transcending the ‘black raven’: An autoethnographic and intergenerational exploration of Stalinist oppression. Qualitative Sociology Review, 9(3), 46–73.

Lai, D. W. L. (2007). Cultural predictors of caregiving burden of Chinese-Canadian family caregivers. Canadian Journal on Aging, 26, 133–147. https://doi.org/10.3138/cja.26.suppl_1.133

Laidlaw, K., Wang, D., Coelho, C., & Power, M. (2010). Attitudes to ageing and expectations for filial piety across Chinese and British cultures: A pilot exploratory evaluation. Aging and Mental Health, 14(3), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903483060

Leek, J., & Rojek, M. (2021). ICT tools in breaking down social polarization and supporting intergenerational learning: Cases of youth and senior citizens. Interactive Learning Environments. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1940214

Leek, J. (2021). The role of ICT in intergenerational learning between immigrant youth and non-related older adults: Experiences from Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(6), 1114–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1833238

Li, J. (2009). Forging the future between two different worlds: Recent Chinese immigrant adolescents tell their cross-cultural experiences. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24(4), 477–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558409336750

Li, M., Guo, M., Stensland, M., Silverstein, M., & Dong, X. (2019). Typology of family relationship and elder mistreatment in a US Chinese population. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 67 (S3). https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15892.

Li, Y. (2014). Intergenerational conflict, attitudinal familism, and depressive symptoms among Asian and Hispanic adolescents in immigrant families: A latent variable interaction analysis. Journal of Social Service Research, 40(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2013.845128

Liddell, B. J., Batch, N., Hellyer, S., Bulnes-Diez, M., Kamte, A., Klassen, C., Wong, J., Byrow, Y., & Nickerson, A. (2022). Understanding the effects of being separated from family on refugees in Australia: A qualitative study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13232

Lim, S. L., Yeh, M., Liang, J., Lau, A. S., & McCabe, K. (2009). Acculturation gap, intergenerational conflict, parenting style, and youth distress in immigrant Chinese American families. Marriage and Family Review, 45(1), 84–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494920802537530

Lin, N. J., Suyemoto, K. L., & Kiang, P. N. C. (2009). Education as catalyst for intergenerational refugee family communication about war and trauma. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 30(4), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740108329234

Liu, S. W., Zhai, F., & Gao, Q. (2017). Parental acculturation and parenting in Chinese immigrant families: The mediating role of social support. China Journal of Social Work, 10(2), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/17525098.2017.1416992

Löbel, L.-M. (2020). Family separation and refugee mental health–A network perspective. Social Networks, 61(May), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2019.08.004

Maher, S., Blaustein, J., Benier, K., Chitambo, J., & Johns, D. (2020). Mothering after Moomba: Labelling, secondary stigma and maternal efficacy in the post-settlement context. Theoretical Criminology, 26(2), 304–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/136248062098163

Mak, C., Lewis, D. C., & Seponski, D. M. (2021). Intergenerational transmission of traumatic stress and resilience among Cambodian immigrant families along coastal Alabama: Family narratives. Health Equity, 5(1), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2020.0142

Mao, W., Xu, L., Guo, M., & Chi, I. (2018). Intergenerational support and functional limitations among older Chinese immigrants: Does acculturation moderate their relationship? Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 27(4), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2018.1520170

Marcus, A., Begum, P., Alsabahi, L., & Curtis, R. (2019). Between choice and obligation: An exploratory assessment of forced marriage problems and policies among migrants in the United States. Social Policy and Society, 18(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746417000422

Mavhandu-Mudzusi, A. H. (2019). Are ‘blessers’ a refuge for refugee girls in Tshwane, the capital city of South Africa? A phenomenographic study. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 20(2), 257–270.

McCleary, J. S., Shannon, P. J., Wieling, E., & Becher, E. (2020). Exploring intergenerational communication and stress in refugee families. Child and Family Social Work, 25(2), 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12692

Mendez, I. (2015). The effect of the intergenerational transmission of noncognitive skills on student performance. Economics of Education Review, 46, 78–97.

Merali, N. (2002). Perceived versus actual parent-adolescent assimilation disparity among Hispanic refugee families. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 24(1), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015081309426

Merali, N. (2004). Individual assimilation status and intergenerational gaps in Hispanic refugee families. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 26(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ADCO.0000021547.83609.9d

Merali, N. (2005). Perceived experiences of Central American refugees who favourably judge the family’s cultural transition process. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 27(3), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-005-8198-4

Merz, E. M., Özeke-Kocabas, E., Oort, F. J., & Schuengel, C. (2009). Intergenerational family solidarity: Value differences between immigrant groups and generations. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015819

Miller, A., Hess, J. M., Bybee, D., & Goodkind, J. R. (2018). Understanding the mental health consequences of family separation for refugees: Implications for policy and practice. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(1), 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000272

Mulholland, M., Robinson, K., Fisher, C., & Pallotta-Chiarolli, M. (2021). Parent–child communication, sexuality and intergenerational conflict in multicultural and multifaith communities. Sex Education, 21(1), 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2020.1732336

Mwanri, L., Okyere, E., & Pulvirenti, M. (2018). Intergenerational conflicts, cultural restraints and suicide: Experiences of young African people in Adelaide, South Australia. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20(2), 479–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-017-0557-9

Nguyen, D. J., Kim, J. J., Weiss, B., Ngo, V., & Lau, A. S. (2018). Prospective relations between parent-adolescent acculturation conflict and mental health symptoms among Vietnamese American adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000157

North, M. S., & Fiske, S. T. (2012). An inconvenienced youth? Ageism and its potential intergenerational roots. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 982–997. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027843

Onraet, E., van Hiel, A., Valcke, B., & van Assche, J. (2021). Reactions towards asylum seekers in the Netherlands: Associations with right-wing ideological attitudes, threat and perceptions of asylum seekers as legitimate and economic. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(2), 1695–1712. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez103

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Park, B. C. B. (2003). Intergenerational conflict in Korean immigrant homes and its effects on children’s psychological well-being. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 1(3), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1300/J194v01n03_06

Phillimore, J. (2021). Refugee-integration-opportunity structures: Shifting the focus from refugees to context. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(2), 1946–1966. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa012

Phinney, J. S., Ong, A., & Madden, T. (2000). Cultural values and intergenerational value discrepancies in immigrant and non-immigrant families. Child Development, 71(2), 528–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00162

Renzaho, A. M. N., Dhingra, N., & Georgeou, N. (2017). Youth as contested sites of culture: The intergenerational acculturation gap amongst new migrant communities-parental and young adult perspectives. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e0170700. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170700

Renzaho, A. M. N., McCabe, M., & Sainsbury, W. J. (2011). Parenting, role reversals and the preservation of cultural values among Arabic speaking migrant families in Melbourne. Australia. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(4), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.09.001

Reynolds, T., Erel, U., & Kaptani, E. (2018). Migrant mothers: Performing kin work and belonging across private and public boundaries. Families, Relationships and Societies, 7(3), 365–382. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674318x15233476441573

Rizkalla, N., Mallat, N. K., Arafa, R., Adi, S., Soudi, L., & Segal, S. P. (2020). ‘Children are not children anymore; they are a lost generation’: Adverse physical and mental health consequences on Syrian Refugee Children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228378

Rogers, C., & Earnest, J. (2014). A cross-generational study of contraception and reproductive health among Sudanese and Eritrean women in Brisbane. Australia. Health Care for Women International, 35(3), 334–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2013.857322

Sangalang, C. C., Jager, J., & Harachi, T. W. (2017). Effects of maternal traumatic distress on family functioning and child mental health: An examination of Southeast Asian refugee families in the U.S. Social Science and Medicine, 184, 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.032

Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Zamboanga, B. L., & Szapocznik, J. (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65(4), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019330

Sellars, M. (2022). Planning for belonging: Including refugee and asylum seeker students. Journal of Refugee Studies, 35(1), 576–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feab073

Sim, A., Bowes, L., & Gardner, F. (2018). Modeling the effects of war exposure and daily stressors on maternal mental health, parenting, and child psychosocial adjustment: A cross-sectional study with Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Global Mental Health (Cambridge, England), 5, e40. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2018.33

Sime, D., & Pietka-Nykaza, E. (2015). Transnational intergenerationalities: Cultural learning in Polish migrant families and its implications for pedagogy. Language and Intercultural Communication, 15(2), 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2014.993324

Singh, S., Sylvia, M. R., & Ridzi, F. (2015). Exploring the literacy practices of refugee families enrolled in a book distribution program and an intergenerational family literacy program. Early Childhood Education Journal, 43(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-013-0627-0

Soaita, A. M., Serin, B., & Preece, J. (2020). A methodological quest for systematic literature mapping. International Journal of Housing Policy, 20(3), 320–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2019.1649040

Spira, M., & Wall, J. (2009). Cultural and intergenerational narratives: Understanding responses to elderly family members in declining health. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 52(2), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634370802561893

Sudha, S. (2014). Intergenerational relations and elder care preferences of Asian Indians in North Carolina”. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 29(1), 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-013-9220-7

Tajima, E. A., & Harachi, T. W. (2010). Parenting beliefs and physical discipline practices among Southeast Asian immigrants: Parenting in the context of cultural adaptation to the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41(2), 212–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022109354469

Terriquez, V., & Kwon, H. (2015). Intergenerational family relations, civic organisations, and the political socialisation of second-generation immigrant youth. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(3), 425–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.921567

Tezcan, T. (2018). On the move in search of health and care: Circular migration and family conflict amongst older Turkish immigrants in Germany. Journal of Aging Studies, 46, 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2018.07.001

Tippens, J. A. (2020). Generational perceptions of support among Congolese refugees in urban Tanzania. Global Social Welfare, 7(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40609-019-00155-2

Tsai, L. P., Barr, J. A., & Welch, A. (2017). Single mothering as experienced by Burundian refugees in Australia: A qualitative inquiry. BMC Nursing, 16 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-017-0260-0

Villani, M., & Bodenmann, P. (2017). FGM in Switzerland: Between legality and loyalty in the transmission of a traditional practice. Health Sociology Review, 26(2), 160–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2016.1254058

Vue, W., Wolff, C., & Goto, K. (2011). Hmong food helps us remember who we are: Perspectives of food culture and health among Hmong Women with young children. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 43(3), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2009.10.011

Warburton, J., & McLaughlin, D. (2007). Passing on our culture: How older Australians from diverse cultural backgrounds contribute to civil society. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 22(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-006-9012-4

Weaver, S. R., & Kim, S. Y. (2008). A person-centered approach to studying the linkages among parent-child differences in cultural orientation, supportive parenting, and adolescent depressive symptoms in Chinese American families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(1), 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9221-3

Willgerodt, M. A., & Thompson, E. A. (2005). The influence of ethnicity and generational status on parent and family relations among Chinese and Filipino adolescents. Public Health Nursing, 22(6), 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.220603.x

Wilson, A., Renzaho, A. M., McCabe, M., Swinburn, B., Wilson, A., Renzaho, A. M. N., McCabe, M., & Swinburn, B. (2010). Towards understanding the new food environment for refugees from the Horn of Africa in Australia. Health & Place, 16(5), 969–976. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.06.001

Wu, C., & Chao, R. K. (2005). Intergenerational cultural conflicts in norms of parental warmth among Chinese American immigrants. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(6), 516–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/01650250500147444

Yasui, M., Kim, T. Y., & Choi, Y. (2018). Culturally specific parent mental distress, parent–child relations and youth depression among Korean American families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(10), 3371–3384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1151-z

Ying, Y. W., & Han, M. (2007a). A test of the intergenerational congruence in immigrant families - Child scale with Southeast Asian Americans. Social Work Research, 31(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/31.1.35

Ying, Y. W., & Han, M. (2007b). The effect of intergenerational conflict and school-based racial discrimination on depression and academic achievement in Filipino American adolescents. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 4(4), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1300/J500v04n04_03

Ying, Y. W., & Han, M. (2008a). Parental acculturation, parental involvement, intergenerational relationship and adolescent outcomes in immigrant Filipino American families. Journal of Immigrant and Refugee Studies, 6(1), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/15362940802119351

Ying, Y. W., & Han, M. (2008b). Parental contributions to Southeast Asian American adolescents’ well-being. Youth and Society, 40(2), 289–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X08315506

Ying, Y.-W., & Han, M. (2007c). The longitudinal effect of intergenerational gap in acculturation on conflict and mental health in Southeast Asian American adolescents. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(1), 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.61

Zhang, J., Cheng, H.-L., & Barrella, K. (2022). Longitudinal pathways to educational attainment and health of immigrant youth in young adulthood: A comparative analysis. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 31(1), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02170-4

Zulfiqar, T., Strazdins, L., & Banwell, C. (2021). How to fit in? Acculturation and risk of overweight and obesity Experiences of Australian immigrant mothers from South Asia and their 8- to 11-year-old children. SAGE Open, 11(3), 215824402110317. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211031798

Funding

This project has been funded by the University of Greenwich Impact Development Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The second, third, and fourth authors contributed equally to this work and are listed in an alphabetical order. All co-authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalocsányiová, E., Essex, R., Hassan, R. et al. Intergenerational Contact in Refugee Settlement Contexts: Results from a Systematic Mapping Review and Analysis. Int. Migration & Integration (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-024-01144-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-024-01144-x