Abstract

Migrants and refugees try to reach Europe to seek protection and a better life. The responsiveness and stewardship of the European countries health system have an impact on the ability to access healthcare. This study aims to investigate the differential probability of healthcare unmet needs among migrants living in four European countries. We used a 2019 cross-sectional data from the European Union Income and Living Conditions survey. We performed a two-stage probit model with sample selection, first to identify the respondents with need for care, then those who need it but have not received it. We analysed reasons for unmet needs through accessibility, availability and acceptability. We then performed country studies assessing the national health systems, financing mechanisms and migration policies. Bringing together data on financial hardship and unmet needs reveals that migrants living in Europe have a higher risk of facing unmet healthcare needs compared to native citizens, and affordability of care remains a substantial barrier. Our results showed the country heterogeneity in the differential migrants’ unmet needs according to the place where they live, and this disparity seems attributed to the health system and policies applied. Given the diversity of socioeconomic conditions throughout the European countries, the health of migrants depends to a large degree on the integration and health policies in place. We believe that EU policies should apply further efforts to respect core health and protection ethics and to acknowledge, among others, principles of ‘do-no-harm’, equity and the right to health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Various reasons bring people to pursue a new life in a different place around the world. Some are looking for a job opportunity or to follow an education, others are forced to flee for fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, nationality, religion or political opinion, and millions flee from war or violence. According to the United Nations (UN, 2020), the estimated number of international migrants worldwide has increased in the last few years, reaching 281 million in 2020 (3.4% of the global population). Eighty million of these migrants were refugees or asylum seekers forcibly displaced from their homes and 10% of them are currently living in the European Union (EU). In 2019, 2.7 million immigrants entered the EU from non-EU countries, and 472,000 asylum applications were lodged in the EU in 2020 (Eurostat, 2022).

Migrants and refugees try to reach the EU to seek protection and a better life. While some use legal ways, others risk their lives at sea or in the hands of traffickers, to escape from political oppression, war, natural disasters and poverty. They frequently carry the burden of their diseases from their country of origin, while others developed it during their traumatic travel experiences, impacting their physical and mental health.

Although migrants are often, at least initially, relatively healthy compared with the non-migrant population in the host country, available data suggest that they tend to be more vulnerable to certain communicable diseases, occupational health hazards, injuries, poor mental health, diabetes mellitus, and maternal and child health problems (Kotsioni et al., 2013; Padovese et al., 2014; Rechel et al., 2011) and may have a much greater need for ongoing care and treatment (BBC News, 2017). Also, there is evidence that migrants are more vulnerable than nationals in some ways and may be less informed and willing to seek legal redress to their issues (Noy & Voorend, 2016). Those factors have subsequently been considered and found with impact on the migrants’ integration process in the country of destination (Jefee-Bahloul et al. 2016; Giannakopoulos and Anagnostopoulos 2016; Fuhr et al. 2019).

Global evidence of migrants’ access to healthcare is scant (Lebano et al., 2020) and generally country-specific, making it difficult to draw comparisons and commonalities across countries (De Vito et al., 2015). Most of the literature has focused on the health status of migrants compared to the local population documenting the differences in the use of health services (Affronti et al. 2011) and showing that inequalities still exist in accessing healthcare (Ho et al., 1997; Tognetti, 2015); some highlighted barriers to access to healthcare such as organisational and administrative issues, also knowledge and language difficulties (Chappuis et al., 2015; Norredam et al., 2010; Sarría-Santamera et al., 2016; Graetz et al. 2017), while others studies (Giannoni et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2013) reported that individuals in an equal state of health but unequal in other characteristics, such as the income level or immigrant status, may have unequal probabilities for accessing healthcare.

Inequalities in healthcare use have been analysed by measuring horizontal equity which is defined as healthcare utilisation according to health needs irrespective of socio-economic status, ability to pay, social or personal background (Van Doorslaer et al., 1992; O’Donnell et al., 2007; Wagstaff & Van Doorslaer 2000). A previous study on Syrian refugees in Egypt (Fares & Puig-Junoy, 2021) observed a pro-rich inequality and horizontal inequity in the probability of refugees’ outpatient and inpatient health services utilisation. Bozorgmehr et al. (2015) also analysed horizontal vertical equity among asylum-seekers in Germany using logistic regression models where the outcome is access to healthcare. The main object of this wide literature was to empirically measure the inequity in the use of healthcare services. In this study, as observed by Guidi et al. (2016), we consider that the study of subjective needs is a proxy much closer to access than utilisation, since, in order to achieve horizontal equity in healthcare, resources should be allocated accordingly to health needs in the societies (Van Doorslaer et al., 2000). In this regard, this paper has not focused on inequity measurement in healthcare utilisation but on the analysis of factors determining healthcare UN at the individual level and the differential probability of migrants’ healthcare UN.

Evidence has shown that if individuals’ health needs are not addressed equitably (d’Uva et al., 2009; Goddard & Smith, 2001), this will result in unmet health needs, inadequate healthcare and inequitable health outcomes (Levesque, 2012; Rodney & Hill 2014). Unmet healthcare need is associated with the treatment and care gap, which refers to the deviation in the proportion of the population in need of services and the proportion that receives them as stated by Kazdin (2017). This unmet need (UN) concept is a subjective measure of access to healthcare. Carr & Wolfe (1976) define it as ‘the differences between services judged necessary to deal appropriately with health problems and services actually received’.

Inequalities in unmet needs for healthcare between natives and migrants within Europe were studied by Guidi et al. (2016) using 2012 cross-sectional data from the European Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). In this study ‘the prevalence of medical unmet needs, adjusted by age and health status, is higher in foreign women, both EU-born and non-EU born, but it is no longer significant after the socioeconomic adjustment’. In the case of dental care unmet needs, some inequalities persisted even after adjusting for socioeconomic variables.

Despite that legal migrants and many refugees may have been granted the right under the national law of the EU member states to access available healthcare, this right does not guarantee that they will be willing or able to (IOM, 2017). Access to healthcare for refugees, asylum seekers and migrants varies across European countries in terms of regulation and laws (Bradby et al., 2015). There is extensive evidence from different European countries (Rechel et al., 2011, 2013) that shows that despite equitable aspirations, inequalities between migrants and non-migrants in health and access to healthcare services persist (Lebano et al., 2020). For example, it has been reported a different prevalence of chronic diseases by citizenship (Buja et al., 2013a). Also, some migrant groups reported much higher levels of unmet medical needs than the general population in Finland (Çilenti et al., 2021).

Often, legal entitlement does not guarantee access and administrative procedures such as requirements for documentation or policies discretionary decisions create barriers to accessibility, this effect has been well documented in the literature (Bradby et al., 2015; De Vito et al., 2015; Matlin et al., 2018). Moreover, the structure and the organisation of health systems, as determined by government policy, have a profound influence on the ability of particular groups to access healthcare (Marmot et al., 2008; O’Donnell et al., 2016). These health policies, which include regulatory, financial and payment regimes, packages of care and entities, affect the structure and performance of the healthcare system, for example social insurance-based systems are particularly problematic for asylum seekers and refugees since registration is more complex than in tax-funded systems as described by Suess et al. (2014).

Furthermore, the European healthcare systems differ among EU countries in several aspects, such as health financing and the range of contribution mechanism, which impacts the medical care granted to citizens and migrants. There are three principal mechanisms for health financing used in Europe (Thomson et al., 2009): (1) the national health system (NHS): the healthcare sector is financed mainly through taxation and access is nearly universal (as in Spain); (2) the social health insurance (SHI): it is the main healthcare finance system in most of the EU countries (as in Germany and France); and (3) out-of-pocket payment (OOP): these payments can be in the form of direct payments for services not covered by the statutory benefits package, cost-sharing (user charges) for services covered by the benefits package, or informal payments (as in Greece).

The responsiveness of the national health system in terms of the availability of services, the model of health insurance, the extent of healthcare coverage and out-of-pocket payments can impact migrants’ ability to access healthcare (Wendt, 2009). The EU member states have formally recognised the right of every person to attain the highest standard of physical and mental health, even though provisions to address the migrants’ and refugees’ health needs remain inadequate and often unmet (Macfarlane et al., 2015).

In this study, we examine the variables related to unmet healthcare requirements among documented migrants from four EU member states: Germany, France, Spain and Greece, using the 2019 wave of Eurostat EU-SILC data. By employing more recent data and a different model approach, the current work adds to the recent contributions of the literature in Guidi et al. (2016). Using a bivariate probit model with sample selection, we examine if the migrant population has a need for healthcare and whether these needs are being met by the present healthcare infrastructure in the host country.

These four countries have been the main destination for migrants in 2020, with 102,500 applications for international protection registered in Germany which accounts for 24.6% of all first-time applicants in the EU, followed by Spain (86,400, or 20.7%), France (81,800, or 19.6%), ahead of Greece (37,900, or 9.1%) (Eurostat, 2022). Migrants also included asylum seekers and refugees in the population data reported to Eurostat. As access to health is related both to legal entitlements and to the existence of barriers to utilising healthcare, two main components are considered in the analysis of the four member states: the health system stewardship on how government actors take responsibility for the health system and legislation in regard to the well-being of the migrants and refugees and their equal access to healthcare; and the national health financing mechanisms from the point of view of financing schemes (financing arrangements through which health services are paid for and obtained by people, e.g. social health insurance) and types of revenues of financing schemes (e.g. social insurance contributions) (OECD, 2019).

Elsewhere, many studies have demonstrated that effective integration policies and socioeconomic security should be encouraged as they may reduce health risks for migrants and refugees (Hadjar & Backes, 2013; Ikram et al., 2015, Malmusi 2015; Giannoni et al., 2016). Accordingly, we provide a secondary descriptive review of reasons of the disparity between the four countries in terms of the health systems and migrant integration policies that could affect migrants’ and refugees’ access to healthcare and explain potential variation in UM.

This study aims to investigate the differential probability of healthcare unmet needs among migrants living in four EU member states—Germany, France, Spain and Greece—and to draw comparisons between those EU countries, taking into consideration the disparities in the health system observed through financing and contribution mechanisms and the migration policies.

Methods

Data

Our data were drawn from the 2019 wave of the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) survey for a set of 4 countries: Germany, Greece, Spain and France.

EU-SILC is the EU reference source for comparative statistics on income distribution and social exclusion at European level; it provides two types of annual data: (1) cross-sectional data pertaining to a given time or a certain time period (1-year period) and (2) longitudinal data pertaining to individual-level changes over time, observed periodically over a 4-year period.

In this study, we used the 2019 cross-sectional data where information on social exclusion conditions, labour, education, health information and income variables were obtained from individuals aged 16 and over.

In order to assess migrant integration policies in European countries, we use MIPEX data for 2020 the latest available year of the survey (MIPEX, 2020). The Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) covering 38 European countries was developed as a tool to monitor policies affecting migrant integration in different countries; it includes policies related to labour market mobility, family reunion, education, health, political participation, permanent residence, access to nationality and anti-discrimination. Research activities are coordinated by the Migration Policy Group, in cooperation with the research partners. Our MIPEX data cover the 2020 global policy and the health policy index in the 4 countries (Solano & Huddleston, 2020).

Finally, the country’s health financial indicators were obtained from the Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat, 2019) and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2019).

Outcome Variable: Unmet Needs

The outcome of interest was a binary indicator variable derived from the question, ‘Was there any time during the last 12 months when, in your opinion, you needed a medical examination or treatment for a health problem, but you did not receive it?’ This question differentiates between medical and dental care, but in our analysis, we treat them together. Only those who reported needing a medical or dental examination or treatment in the previous 12 months were asked this question. Our outcome variable aims to capture the restricted access to medical and dental care via the person’s own assessment.

Explanatory Variables

Following the previous empirical literature on explanatory factors of unmet need, our selection of independent variables tried to include all those factors related to the underlying reasons for UN which are available in the EU-SILC. The more usually used explanatory variables are age, nationality and marital status that represent socio-demographic characteristics, and chronicity which is used as a proxy of health status; also, some studies also test for the relevance of supply as a UN determinant and include educational level, labour status and household income in order to represent the socioeconomic position of individuals (Hernandez-Quevedo et al., 2010; Urbanos Garrido 2020; Chung, 2022). In the study of Guidi et al. (2016), which analysed the determinants of migrants’ UN using the 2012 EU-SILC, the following variables were considered as potential explanatory factors: age, education, working position, activity status, equivalised income, ability to make ends meet, access to healthcare services, self-health assessment, chronic diseases and limitations in activities.

This study uses socioeconomic and demographic characteristics as explanatory variables. These variables include the age (18 years old and older), gender (coded 1 = female, 0 = male), log-transformed equivalent household income using the OECD scale, self-perceived general health (coded 1 = very bad, 2 = bad, 3 = fair, 4 = good and 5 = very good), self-reported chronic illness (coded 1 = yes, 0 = no), country of survey (coded 1 = Germany, 2 = Greece, 3 = Spain and 4 = France) and migrant status (coded 1 = yes, 0 = no).

The migrant status variable is obtained from the variable being a recognised-non-born and non-European citizen. In the EU-SILC, a recognised non-European citizen is a person who is not a citizen of the reporting country nor any other EU country, but who has established links to that country which include some but not all rights and obligations of full citizenship.

Migrant variable included asylum seekers, refugees and other migrants who are usual residents for at least 12 months and living in a private house; however, differentiation between the immigrant statuses was not included.

Statistical Analysis

Unmet needs being analysed using a probit model with sample selection, with reference to its usage in Davin et al. (2006), Gannon & Davin (2010) & Chung (2022). The probit model is used as a correction device for sample selection in our two-stage construction of the dependent variable: in the first stage, we identify who are the respondents with need for care and in the second stage who are those who need it but do not receive it? Fig. 1 describes the process involved in our analysis.

The main probit model assumes that there exists an underlying relationship:

such that we observe only the binary outcome:

where \({y}_{1}^{*}\) is a latent variable measuring the propensity of unmet needs for medical or dental care, \({\varvec{X}}\) is a set of control variables that incorporates the log-transformed equivalent household income, the country of survey and migrant status, and \({u}_{1}\) is the error term normally distributed with a mean of 0 and standard deviation 1. In order to allow that the difference in the unmet needs for medical or dental care between migrant and recognised European citizens can be different according to each country of the survey, we add to the model a new variable which is the interaction between these two categorical variables.

However, it must be taken into account that the dependent variable \({y}_{1}^{*}\) is only observed when respondents reported needed medical or dental examination or treatment during the last 12 months \({y}_{2}^{*}>0\) according to the selection equation:

where \({y}_{2}^{*}\) is a latent variable too, \({\varvec{Z}}\) is a vector of explanatory variables related to the need for medical or dental care, and \({u}_{2}\) is the error term normally distributed with a mean of 0 and standard deviation 1. We use the correlation coefficient \(\rho\) between \({u}_{1}\) and \({u}_{2}\) to test for sample selection bias.

We estimate \(\beta\), \(\gamma\) and \(\rho\) jointly use a full maximum-likelihood procedure. For this, we use the heckprob procedure in STATA 17 (StataCorp, 2021) Stata Statistical Software: Release 17, Stata Press, College Station, TX, USA. In order to handle the within-countries correlation arising from the nested nature of the data (households within countries), we clustered the standard errors by country employing a robust cluster estimation. Data were weighted to adjust for survey design.

Finally, we calculate the average marginal effects of the regressors of interest, that is, the conditional (on selection) predicted probability of the unmet need for medical or dental care.

A p < 0.05 cut-off was used to determine the statistical significance of all analyses.

Country Case Studies

This section contains country information related to the health system stewardship and policy toward migrants, refugees and asylum seekers and the national health financing mechanisms.

Spain has experienced a sharp increase in the number of migrants (both documented and undocumented) over the past few years (IOM, 2017, 2019). Many migrants are now choosing Spain as an alternate gateway to Europe given the recent deals to shut routes and restrict migration to Italy and Greece.

Spain health policy has shifted from one of exclusivity as seen in the Royal Decree Law in 2012 (RDL 16/2012) to one that more recently proclaims free access beyond emergency care to primary care to all, regardless of immigration or citizenship status (Legido-Quigley et al., 2018).

Spain has a tax-based system of healthcare where a near-universal public health system provides coverage to 99.1% of the population with entitlement based on social security working status. Direct state funding through general taxation is the main source of healthcare financing in Spain.

France has long been a destination country for migrants, asylum seekers and refugees, and in 2018 migrants represented 9.7% of the total population.

In France, the health system aims to be inclusive and accessible to migrant patients. As such, the same principles apply to legal residents as to French citizens. Asylum seekers are also covered by the universal free health insurance system (Couverture Universelle Maladie Protection Complémentaire; CMU-C). Low-income irregular migrants are covered by state medical aid (Aide Médicale d’Etat) with certain conditions and restrictions.

The French national health system is funded through taxation and personal contributions. Social security health coverage is based on a system where ‘everyone pays according to their means and receives according to their needs’. This covers approximately 65% of healthcare expenses and every person legally residing in France is entitled to it (Kulesher & Forrestal, 2014).

Germany has increased the support and solidarity to refugees and migrants since the Syrian crisis, by December 2018, there were 1.8 million people with a refugee background in Germany (including beneficiaries of international protection and asylum seekers) (Simonet, 2010).

Persons with refugee status and beneficiaries of subsidiary protection have the same status as German citizens within the social insurance system. This includes membership in the statutory health insurance, if they are unemployed, the job centre or the social welfare office provides them with a health insurance card which entitles them to the same medical care as statutory health insurance.

Germany healthcare benefits are financed through national insurance contributions made by the worker and/or their employer, while everyone who legally resides in Germany must be covered by health insurance (public or private).

Like France, Germany has increased their reliance on income not related to earnings, through tax allocations—a move that is likely to contribute to fiscal sustainability in the context of rising unemployment, growing informal economies and concerns about international competitiveness.

Greece is the first country of arrival in Europe for irregular migrants and asylum seekers. At the end of 2019, Greece was hosting over 186,000 refugees and asylum-seekers (UNHCR Operational Data Portal, 2019), besides more than 700,000 third-country nationals (Eurostat, 2020).

Free access to healthcare for beneficiaries of international protection is provided under the same conditions as for nationals, pursuant to Article 33 of Law 4368/2016 by the Ministry of Health. The national health system is financed by the state budget, social insurance contributions and private payments. It relies on a mandatory health insurance which is based on work (with employer/employee contributions, which are income-related).

Thus, health services are funded by individual contributions (insurance-based) but also by state subsidies (tax-based). Greece has engaged in substantial reforms of its national health system in order to tackle the economic crisis and social difficulties that the country is facing since 2012; this has resulted in the reduction of 40% of the financing of public hospitals and an increase in the co-payment up to 25% of drug costs.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Summary statistics are reported in Table 1. We analysed a total of 109,031 observations, among the adult interviewees (age 18 years old and older), 82,467 (75.64%) reported needed medical or dental care during the last 12 months. Out of 82,467 who needed medical or dental care, 9530 (11.56%) did not receive it.

Most of the observations in the sample were females (52.40). 24.38% of our included individuals reported that self-perceived health status was very good, and 45.22% reported it was good (45.22%). Average age was around 53 years old. About 3.43% (3743 individuals) of the whole sample are recognised-non born, non-European citizens (migrants).

Estimation Results

The selection model for the probability of the need for medical or dental care is shown in the first column in Table 2. Analysis of the selection model reveals that being female, getting older, having declared a self-perceived bad health condition, suffering from a chronic illness and having a low household income are factors that are strongly related to significant positive effects on the likelihood of the need for medical or dental care; these results were coherent with findings in the literature (Nielsen & Krasnik, 2010; Hurley, 2018; Kaoutar, 2014).

The highly significant correlations test between the error terms (ρ) provides evidence of a selection effect suggesting that we correctly modelled the unmet need for medical or dental care conditioned to a prior need for medical or dental care. When ρ ≠ 0, i.e. there is a correlation between error terms of the main and selection equation, then the standard probit model will produce biased results.

Table 2, fourth column, presents the probit model for unmet need for medical or dental care, with correction for sample selection. Results of this probit model show that having a higher level of disposable household income is related to significant negative effects on the likelihood of the unmet need for medical or dental care. The variables migrant status and country of residence, as well as their interaction, show significant results too, with significant differences between countries.

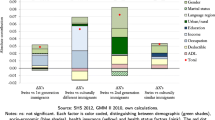

The average marginal effect of the probit model for unmet need for medical or dental care, with correction for sample selection, is shown in Table 3. Holding equivalent income variable at mean value, the conditional predicted probability of unmet need for medical or dental care is 4.09% among those migrants who reside in Germany, 39.33% among those migrants who reside in Greece, 10.63% among those migrants who reside in Spain and 11.38% among those migrants who residing in France. Being a migrant significantly increases the likelihood of an unmet need for medical or dental care in all countries (p value < 0.0001).

Finally, the results of the tests in Table 4 show significant differences in the probability of the unmet need for medical or dental care between the countries in the survey when the migrant status = yes (p value < 0.0001), except between Spain and France (p value = 0.3055)

We categorised self-declared reasons for unmet needs into three main categories as described in the literature (Pappa et al., 2013): (1) accessibility when the reason was related to cost affordability and proximity of service; (2) availability when the reason was related to the timely provision of health services and the waiting list; and (3) acceptability when the reason is related to personal attitudes and other circumstances.

In Table 5, we investigated the distribution of the reasons for which self-assessed needed healthcare is not received accounting for the variation in the four selected countries. We found that the main reason for the unmet needs in dental care was the accessibility in terms of cost and proximity which was strongly conveyed in Greece and Spain. The other reasons for unmet needs in medical care were related to the acceptability in terms of personal attitudes and circumstances. A significant difference was observed between the four countries.

Table 6 presents the country’s characteristics as highlighted in the literature (Cylus et al., 2012; Pappa et al., 2013; Malmusi, 2015; Carballo et al. 1998), which may influence access to healthcare for migrants. The 2020 global Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) in the 4 countries (Solano & Huddleston, 2020) shows that Germany received the highest score among all countries, scoring 58 points out of 100, compared to 56 for France and Spain and 46 for Greece. The MIPEX health score results locate Greece another time at the end of the list with a score of 48 points compared to a quite similar score in the other three countries: 63 points for Germany and 65 points for both France and Spain.

We also noted that the out-of-pocket payment (OOP) as a health financing mechanism was the highest in Greece while the health expenditure as a percentage of GDP was the lowest.

Discussion

Survey data has been commonly used to ascertain individuals’ perceptions of unmet needs arising from various barriers to accessing care (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2019). Similar to other studies (Cavalieri, 2013; Chaupain-Guillot & Guillot 2015; Guidi et al., 2016; Connolly & Wren, 2017; Fiorillo, 2020), we investigated unmet needs within and across European countries using data from the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). In our study sample, factors such as being a female, getting older, having declared a bad health condition, suffering from a chronic illness and having a low household income are strongly related to significant positive effects on the likelihood of the need for medical or dental care. We also noted that low-income households in the four EU countries are more likely to report unmet needs compared to national communities, in accordance with the literature (Giannoni et al., 2016; Popovic et al., 2017; Quintal et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2013).

Migrant was not found as a significant determining factor to express a medical or dental care need; however, we found that in the four EU countries included in our study, migrants have more healthcare UN than non-migrants (p value < 0.0001). This means that the availability of the service does not seem to be the main reason for the limited access, while the affordability of care, confusion about the system and the failure of healthcare providers may play a significant role (Frank et al., 2017; Taglieri et al., 2013; Violini, 2015). Residency in an EU country does not seem sufficient to ease the barriers to healthcare access for the migrant population. Our findings were in accordance with previous surveys in China (Lu, et al., 2016) and Italy (Buja et al., 2013b), while other studies suggested that migrants were more inclined to ignore health issues, which results in more unmet healthcare needs (De Back et al., 2015; Shao et al., 2018). In this sense, Matlin et al. (2018) have looked at various issues regarding migrants’ health needs globally and highlighted the existence of a discrepancy between emphasis on health rights and equity on the one hand and the actual provision of equal healthcare on the other, as our results on the marginal effect of the probability of healthcare unmet needs for the migrants, with heterogeneous country effects, suggest.

Some studies explained effectively how health systems are structured and the extent of people’s and migrants’ entitlements (Matlin et al., 2018; Rechel et al., 2011). Our results show country heterogeneity in the differential healthcare migrants’ UN according to the country where they are living. In this paper, we empirically tested migrants’ UN for healthcare through two main aspects. Firstly, the characteristics of individuals seeking care, which are directly related to the acceptability and affordability of healthcare, including patients’ socioeconomic status, social capital, the perception of the benefits and the quality of the services. And, secondly, we tested differential migrants’ UN in relation to the characteristics of the health system, which include availability and accessibility of healthcare services. Whereas the major variability of UN appears related to individual factors (Allin & Masseria, 2009; Guidi et al., 2016; Herr et al., 2014), in our study, we noted a significant difference in the likelihood of a migrant facing unmet needs living in one country compared to the others, suggesting that the country of residence determines the extent of healthcare services that could be offered and received by the migrants.

WHO highlighted that any health discrepancies between migrants and non-migrants disappear after controlling for socioeconomic status (WHO, 2010), though poor socioeconomic status might itself be a result of migrant status and ethnic origin, because of processes of social exclusion (Davies et al., 2009; Ingleby, 2009). Also, Guidi et al. (2016), using 2012 data, concluded that the differential prevalence of medical and dental UN is not statistically significant after adjustment for socioeconomic variables, except in the case of dental UN (men and women). However, our results, using a more recent dataset (2019 year), holding the economic income at the mean value for all migrant populations, provided evidence that those migrants living in Germany presented less probability (4.09%) of declaring unmet need for medical and dental care, compared to migrants residing in Spain or France with 10.63% and 11.38%, respectively, and comparing to Greece which presents the uppermost probability of unmet need with 39.33%.

Policies designed to mitigate healthcare UN play a significant role in reducing health inequality and fulfilling the goal of universal health coverage (Ronksley et al., 2012). According to Bradby et al. (2015) and O’Donnell et al. (2016), the characteristics of the health system and the extent of the out-of-pocket payments can impact populations and individuals’ ability to access healthcare. Hence, to further investigate this variability, we underwent a scoping descriptive review of the health policies in the four countries of our study. We observed the out-of-pocket (OOP) as % of current health expenditure (CHE) from the Eurostat database of 2019, as presented in Table 6, and found Greece, where UNs were the highest among the four countries, has as well the highest reliance on OOP with 36% of CHE, compared to the other three countries. Heavy reliance on out-of-pocket payments, basing population entitlement on factors other than the country of residence, is likely to delay care-seeking, increase financial hardship and unmet needs, and exacerbate inequalities in access to care among already vulnerable groups of migrants and refugees (Thomson et al., 2015).

Our findings also suggest that the variations in rates of unmet need between countries could be partly explained by the differences in financing modality in the healthcare systems. These results have been put forward in another study by Connolly and Wren (2017). Assessing the characteristic of the health system in the four countries, we found that in Germany, healthcare benefits are financed through national insurance contributions made by the worker and/or their employer, while everyone who legally resides in Germany must be covered by health insurance (public or private). In France, the insurance system is funded primarily by payroll taxes (paid by employers and employees), a national income tax, and tax levies on certain industries and products, and in Spain, healthcare benefits are financed mainly through general taxation (tax-based healthcare system). While in Greece, the system is financed by the state budget, social insurance contributions and private payments; the largest share of health expenditure is constituted by the private one, mainly in the form of out-of-pocket payments, which is also the element contributing most to the overall increase in health expenditure. The high percentage of private expenditure goes against the principle of fair financing and equity in access to healthcare services.

Few studies (Giannoni et al., 2016; Hadjar & Backes, 2013; Ikram et al., 2015) have highlighted a third element that would influence access to healthcare which is policies related to integration and that could be aggregately measured using the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) (Vearey, 2016). Our secondary descriptive analysis of the data from the 2020 Migrant Integration Policy Index in the four countries may be interpreted to be in alignment with the earlier econometric analysis performed in this paper, given that the country with the lowest MIPEX scores both globally and related to health, Greece in our study, also presented the uppermost probability of UN. While all four EU countries have migrant integration policies which attempt to address protection and human rights principles, major disparities remain between member states’ application of those policies, which has an impact on the unmet needs and aggravates the risk conditions of migrants and refugees in Europe.

Limitations and Strength

In the EU-SILC dataset for research purposes, information on birthplace is aggregated into the country of residence, the rest of the EU and outside of the EU. The main limitation of the study could be not to identify the nature of immigrants being refugees, asylum seekers or legal migrants, which restricts the depth of understanding of the protection challenges and health needs of each of those groups. Thus, it would have been more informative to compare populations with different ethnic and migration backgrounds (Villadsen et al. 2010).

Furthermore, the largest endogeneity concern in our study was selection bias, which we addressed through our two-stage selection model. Another potential source of endogeneity is the strong relationship between income and health. For most age groups, men and women from lower social classes have worse self-perceived general health than those from higher social classes. However, in our data, the fact that the self-perceived general health refers to the last 12 months avoids that a significant percentage of the variance in one measure can be explained by the other.

Moreover, and concerning the data source, the EU-SILC is a harmonised dataset of country surveys that can present heterogeneity in methods of sampling, data collection and response rates (Iacovou et al., 2012). Limited participation and representation of immigrants in population surveys have been observed and could present an issue (González-Rábago et al. 2014). However, these surveys have standardised quality procedures and collect health and social exclusion outcomes that allow reasonably consistent comparisons across countries. To our knowledge, this is the first study to draw comparisons and affirm disparities between four countries in the EU regarding the probability of unmet needs and access to healthcare for migrants and refugees living in Europe.

Finally, our statistical model provides certain advantages over the multivariate logistic regression models used in other papers (Cavalieri, 2013; Moran et al., 2021). These papers use logistic regression to estimate the effect of a vector of variables on the unmet need for medical care. With a random sample of individuals, logistic regressions would produce an unbiased and efficient estimate of this effect. However, the unmet need for medical care is only available for individuals that needed medical care during the last 12 months, leading to a non-random sample. When non-random samples are used, the presence of sample selection bias can lead to flawed conclusions. Our two-stage approach deals with the presence of this sample selection bias.

Conclusion

This study used European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) survey to investigate the differential probability of unmet health needs for migrants in 4 EU countries. While the database, however inclusive, did not differentiate the nature of migrants (refugees, asylum seekers or legal migrants), yet we extrapolate, without distinction, the findings to all migrant categories for policy advocacy purposes.

Bringing together data on financial hardship and unmet needs across four countries in Europe reveals that migrants and refugees living in Europe have a higher risk of facing unmet healthcare needs compared to native citizens. Affordability of care remains a substantial barrier for many migrants who reside in Europe, while the availability of services does not seem sufficient to guarantee access to that service.

We found a significant variation between migrants’ unmet health needs residing in the four EU countries, and this disparity seems to be attributed to the structure of the national health system, policies to support migrants and financing healthcare mechanisms.

Given the vast diversity of socioeconomic and living conditions throughout European countries, the health of migrants also depends to a large degree on the specifics of the host country. Reviewing and comparing the policies of the four EU member states displayed to which extent, health financing mechanisms can exacerbate or mitigate the threat of financial risk of ill health. The higher reliance on out-pocket contribution, as seen in Greece, is met with a greater likelihood to face unmet needs.

Co-payment and out-of-pocket design (private financing) are key factors influencing financial protection. Considering exemptions for vulnerable refugees and migrants appears to be the most effective co-payment design feature in terms of access to healthcare and financial protection.

Migration is a common phenomenon in Europe, and migrants will continue to make up a growing share of the European population. The term ‘integration’ seems still poorly understood and differently applied throughout the EU member states. The European institutions defined integration as a two-way process in which both the host country and the migrants themselves are responsible (European Commission, 2011), whereas migrants are not a homogeneous group and improving their integration and consequently, their access to healthcare should consider biological demography, social determinants and individual behaviours.

Additionally, services for migrants are dynamic and impacted by several factors as providers’ behaviours and individual attitudes but also by the health need of migrants and their family members, with reference to the underlying health system, legal implications and social values.

The marginal effect of the probability of healthcare unmet needs for the migrants and the heterogeneous of the country effects in our study display the existence of a discrepancy between the EU emphasis on health rights and equity on one hand and the actual provision of equal healthcare on the other.

We believe that EU policies should apply further efforts to respect core ethics related to health and protection and to acknowledge, among others, the principles of ‘do-no-harm’, equity and the right to health.

Finally, migrants’ health calls for adapted information systems with the ability to disaggregate populations by refugee, asylum seeker or migrant status. This will enable the monitoring of services with humanitarian standards and indicators, as well as provide public health and policymakers with better, more accurate information.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from third parties; applications for access to anonymised EU-SILC survey microdata files for research purposes are handled by Eurostat.

Abbreviations

- CHE:

-

Current health expenditure

- EU:

-

European Union

- EU-SILC:

-

European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- MIPEX:

-

Migrant Integration Policy Index

- OOP:

-

Out-of-pocket payment

- UN:

-

Unmet need

- UNHCR:

-

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

References

Affronti, M., Affronti, A., Pagano, S., Soresi, M., Giannitrapani, L., Valenti, M., La Spada, E., & Montalto, G. (2011). The health of irregular and illegal immigrants: Analysis of day-hospital admissions in a department of migration medicine. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 8(7), 561–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-0110635-2

Allin, S., & Masseria, C. (2009). Research note: Unmet need as an indicator of access to healthcare in Europe. Anonymous The London school of Economics and Political Science: European Commission Directorate-General “Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities” Unit E1–Social and Demographic Analysis, from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/28454/

BBC News (2017). Migrant crisis: Migration to Europe explained in seven charts. BBC, from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34131911. Accessed 1 Dec 2020

Bozorgmehr, K., Schneider, C., & Joos, S. (2015). Equity in access to health care among asylum seekers in Germany: Evidence from an exploratory population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research, 15, 502. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1156-x

Bradby, H., Humphris, R., Newall, D., & Phillimore, J. (2015). Public health aspects of migrant health: A review of the evidence on health status for refugees and asylum seekers in the European region, . from http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/289246/WHO-HEN-Report-A5-2-Refugees_FINAL.pdf?ua=1

Buja, A., Gini, R., Visca, M., Damiani, G., Federico, B., Francesconi, P., Donato, D., Marini, A., Donatini, A., Brugaletta, S., Baldo, V., Bellentani, M., Valore Project. (2013). Prevalence of chronic diseases by immigrant status and disparities in chronic disease management in immigrants: A population-based cohort study. Valore Project. BMC Public Health, 13, 504. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-504

Buja, A., Gini, R., Visca, M., Damiani, G., Federico, B., Francesconi, P., Donato, D., Marini, A., Donatini, A., Brugaletta, S., Baldo, V., Bellentani, M., Valore Project. (2013). Characteristics, processes, management and outcome of accesses to accident and emergency departments by citizenship. International Journal of Public Health, 59(1), 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-013-0483-0

Carballo, M., Divino, J. J., & Zeric, D. (1998). Migration and health in the European Union. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 3(12), 936–944. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00337.x

Carr, W., & Wolfe, S. (1976). Unmet needs as sociomedical indicators. International Journal of Health Services., 6(3), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.2190/MCG0-UH8D-0AG8-VFNU

Cavalieri, M. (2013). Geographical variation of unmet medical needs in Italy: A multivariate logistic regression analysis. International Journal of Health Geographics, 12(1), 1–117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-12-27

Chaupain-Guillot, S., & Guillot, O. (2015). Health system characteristics and unmet care needs in Europe: An analysis based on EU-SILC data. The European Journal of Health Economics, 16(7), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-014-0629-x

Chappuis, M., Tomasino, A., & Didier, E. (2015). Observatoire de l’accès aux droits et aux soins de la mission France de Médecin du Monde. https://www.medecinsdumonde.org/app/uploads/2022/04/MDM-RAPPORT-OBSERVATOIRE-2016.pdf

Chung, W. (2022). Changes in barriers that cause unmet healthcare needs in the life cycle of adulthood and their policy implications: A need-selection model analysis of the Korea health panel survey data. Healthcare, 10, 2243. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112243

Çilenti, K., Rask, S., Elovainio, M., Lilja, E., Kuusio, H., Koskinen, S., Koponen, P., & Castaneda, A. E. (2021). Use of health services and unmet need among adults of Russian, Somali, and Kurdish origin in Finland. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 18, 2229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052229

Connolly, S., & Wren, M. A. (2017). Unmet healthcare needs in Ireland: Analysis using the EU-SILC survey. Health policy, 121(4), 434–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.02.009

Cylus, J., Mladovsky, P., & McKee, M. (2012). Is there a statistical relationship between economic crises and changes in government health expenditure growth? An analysis of twenty-four European countries. Health Services Research, 47(6), 2204–2224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01428.x

Davies, A., Basten, A., & Frattini, C. (2009). Migration: A social determinant of migrants’ health. Eurohealth, 16(1), 10–12. from https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/122710/Eurohealth_Vol-16-No-1.pdf.

Davin, B., Joutard, X., Moatti, J. P., et al. (2006). Besoins et insuffisance d’aide humaine aux personnes âgées à domicile : une approche à partir de l’enquête « Handicaps, incapacités, dépendance ». Sciences Sociales et Santé, 24, 59–93. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0013/122710/Eurohealth_Vol-16-No-1.pdf.

De Back, T. R., Bodewes, A. J., Brewster, L. M., & Kunst, A. E. (2015). Cardiovascular health and related healthcare use of Moluccan-Dutch immigrants. PloS One, 10(9), e0138644. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138644

De Vito, E., De Waure, C., Specchia, M. L., & Ricciardi, W. (2015). Public health aspects of migrant health: A review of the evidence on health status for undocumented migrants in the European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2015 (Health Evidence Network synthesis report 42), from https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/289255/WHO-HEN-Report-A5-3-Undocumented_FINAL-rev1.pdf

D’Uva, T. B., Jones, A. M., & Van Doorslaer, E. (2009). Measurement of horizontal inequity in healthcare utilisation using European panel data. Journal of Health Economics, 28(2), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.09.008

European Commission. (2011). European agenda for the integration of third-country nationals. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Brussels, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0455&from=EN.

Eurostat (2022). Migration and migrant population statistics from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics#:~:text=%3A%20Eurostat%20(migr_imm2ctz)-,Migrant%20population%3A%2021.8%20million%20non%2DEU%2D27%20citizens%20living,of%20the%20EU%2D27%20population. Accessed 27 Mar 2022

Fares, H., & Puig-Junoy, J. (2021). Inequity and benefit incidence analysis in healthcare use among Syrian refugees in Egypt. Conflict & Health, 15, 78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-021-00416-y

Fiorillo, D. (2020). Reasons for unmet needs for healthcare: The role of social capital and social support in some Western EU countries. International Journal of Health Economics and Management, 20(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-019-09271-0

Frank, L., Yesil-Jürgens, R., Razum, O., Bozorgmehr, K., Schenk, L., Gilsdorf, A., & Lampert, T. (2017). Gesundheit und gesundheitliche Versorgung von Asylsuchenden und Flüchtlingen in Deutschland. Journal of Health Monitoring, 2(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.17886/RKI-GBE-2017-005

Fuhr, D. C., Ataturk, C., McGrath, M., Ilkkursun, Z., Woodward, A., Sondorp, E., & Roberts, B. (2019). Treatment gap and mental health service use among Syrian refugees in Turkey. European Journal of Public Health, 29(Supplement_4), ckz185-579. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.579

Gannon, B., & Davin, B. (2010). Use of formal and informal care services among older people in Ireland and France. European Journal of Health Economics, 11, 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-010-0247-1

Giannakopoulos, G., & Anagnostopoulos, D. C. (2016). Child health, the refugees crisis, and economic recession in Greece. The Lancet, 387(10025), 1271. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30016-2

Giannoni, M., Franzini, L., & Masiero, G. (2016). Migrant integration policies and health inequalities in Europe. BMC Public Health, 16, 463. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3095-9

Goddard, M., & Smith, P. (2001). Equity of access to healthcare services: Theory and evidence from the UK. Social Science & Medicine, 53(9), 1149–1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00415-9

González-Rábago, Y., La Parra, D., Martín, U., & Malmusi, D. (2014). Participación y representatividad de la población inmigrante en la Encuesta Nacional de Salud de España 2011–2012. Gaceta Sanitaria, 28(4), 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2014.02.011

Graetz, V., Rechel, B., Groot, W., Norredam, M., & Pavlova, M. (2017). Utilization of healthcare services by migrants in Europe—A systematic literature review. British Medical Bulletin, 121(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldw057

Guidi, C., Palència, L., Ferrini, S., & Malmusi, D. (2016). Inequalities by immigrant status in unmet needs for healthcare in Europe: The role of origin, nationality and economic resources. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies research paper no. RSCAS, 55. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2860634

Hadjar, A., & Backes, S. (2013). Migration background and subjective well-being a multilevel analysis based on the European social survey. Comparative Sociology, 12(5), 645–667. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-12341279

Hernandez-Quevedo C., Masseria C., Mossialos E. Methodological issues in the analysis of the socioeconomic determinants of health using EU-SILC data. Eurostat Methodologies and Working Papers, 2010, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3888793/5847256/KS-RA-10-016-EN.PDF/14ea442a-ef64-4b81-a522-7cee4bd3dbe3

Herr, M., Arvieu, J. J., Aegerter, P., Robine, J. M., & Ankri, J. (2014). Unmet healthcare needs of older people: Prevalence and predictors in a French cross-sectional survey. The European Journal of Public Health, 24(5), 808–813. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt179

Ho, J. H., Chang, R. J., Wheeler, N. C., & Lee, D. A. (1997). Ophthalmic disorders among the homeless and nonhomeless in Los Angeles. Journal of the American Optometric Association, 68(9), 567–573.

Hurley, R. (2018). Challenge anti-migrant policies with evidence, doctors are told. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online), 361, k2266. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2266

Iacovou, M., Kaminska, O., & Levy, H. (2012). Using EU-SILC data for cross-national analysis: Strengths, problems and recommendations (no. 2012–03). ISER working paper series, from on: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/65951/1/686613252.pdf

Ikram, U. Z., Malmusi, D., Juel, K., Rey, G., & Kunst, A. E. (2015). Association between integration policies and immigrants’ mortality: An explorative study across three European countries. PLoS One, 10(6), e0129916. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129916

Ingleby, D. (2009). European research on migration and health. Brussels: International Organization for Migration, from https://aen.es/wp-content/uploads/docs/AMAC_project_background_paper_Ingleby_1st_DRAFT.pdf

International Organization for Migration- IOM (2016). The health of migrants. From www.iom.int/sites/default/files/our_work/ODG/GCM/IOM-Thematic-Paper-Health-of-Migrants.pdf. Accessed 18 Aug 2020

IOM (2017). Summary report on the MIPEX health strand and country reports. UN, from https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/mrs_52.pdf. Accessed 18 Aug 2020

IOM (2019). World migration report 2020, from https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf. Accessed 18 Aug 2020

Jefee-Bahloul, H., Bajbouj, M., Alabdullah, J., Hassan, G., & Barkil-Oteo, A. (2016). Mental health in Europe’s Syrian refugee crisis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(4), 315–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00014-6

Kaoutar, B., Gatin, B., de Champs-Leger, H., Vasseur, V., Aparicio, C., de Gennes, J., Lebas, J., Chauvin, P., & Georges, C. (2014). Socio-demographic characteristics and health status of patients at a free-of-charge outpatient clinic in Paris. La Revue De Médecine Interne, 35(11), 709–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revmed.2014.05.013

Kazdin, A. E. (2017). Addressing the treatment gap: A key challenge for extending evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 88, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.004

Kotsioni, I., Ponthieu, A., & Egidi, S. (2013). Health at risk in immigration detention facilities. Forced Migration Review, 44, 11–13. from https://www.fmreview.org/sites/fmr/files/FMRdownloads/en/detention/kotsioni-et-al.pdf.

Kulesher, R., & Forrestal, E. (2014). International models of health systems financing. Journal of Hospital Administration, 3(4), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.5430/jha.v3n4p127

Lebano, A., Hamed, S., Bradby, H., Gil-Salmerón, A., Durá-Ferrandis, E., Garcés-Ferrer, J., Azzedine, F., Riza, E., Karnaki, P., Zota, D., & Linos, A. (2020). Migrants’ and refugees’ health status and healthcare in Europe: A scoping literature review. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08749-8

Legido-Quigley, H., Pajin, L., Fanjul, G., Urdaneta, E., & McKee, M. (2018). Spain shows that a humane response to migrant health is possible in Europe. The Lancet Public Health, 3(8), e358.

Levesque, J. F., Pineault, R., Hamel, M., Roberge, D., Kapetanakis, C., Simard, B., & Prud’homme, A. (2012). Emerging organisational models of primary healthcare and unmet needs for care: Insights from a population-based survey in Quebec province. BMC Family Practice, 13(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-13-66

Lu, L., Zeng, J., & Zeng, Z. (2016). Demographic, socio-economic, and health factors associated with use of health services among internal migrants in China: An analysis of data from a nationwide cross-sectional survey. The Lancet, 388, S5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31932-8

Macfarlane, A., Dattani, N., & Zeitlin, J. (2015). 6. WC poster walk: Migrant and ethnic minority health. European Journal of Public Health, 25, 3. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv175.272

Malmusi, D. (2015). Immigrants’ health and health inequality by type of integration policies in European countries. The European Journal of Public Health, 25(2), 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku156

Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., Houweling, T. A., Taylor, S., Commission on Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 372(9650), 1661–1669. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6

Matlin, S. A., Depoux, A., Schütte, S., Flahault, A., & Saso, L. (2018). Migrants’ and refugees’ health: Towards an agenda of solutions. Public Health Reviews, 39, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-018-0104-9

MIPEX 2020 Migrant Integration Policy Index, from http://www.mipex.eu. Accessed 18 June 2021

Moran, V., Suhrcke, M., Ruiz-Castell, M., Barré, J., & Huiart, L. (2021). Investigating unmet need for healthcare using the European Health Interview Survey: A cross-sectional survey study of Luxembourg. BMJ open, 11(8), 048.

Nielsen, S. S., & Krasnik, A. (2010). Poorer self-perceived health among migrants and ethnic minorities versus the majority population in Europe: A systematic review. International Journal of Public Health, 55(5), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-010-0145-4

Norredam, M., Nielsen, S. S., & Krasnik, A. (2010). Migrants’ utilization of somatic healthcare services in Europe—A systematic review. European Journal of Public Health, 20(5), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp195

Noy, S., & Voorend, K. (2016). Social rights and migrant realities: Migration policy reform and migrants’ access to healthcare in Costa Rica, Argentina, and Chile. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(2), 605–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0416-2

O’Donnell, O., Van Doorslaer, E., Wagstaf, A. & Lindelow, M. (2007). Analyzing health equity using household survey data: A guide to techniques and their implementation. Washington, DC: The World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/6896

O’Donnell, C. A., Burns, N., Mair, F. S., Dowrick, C., Clissmann, C., van den Muijsenbergh, M., ... & RESTORE Team. (2016). Reducing the healthcare burden for marginalised migrants: The potential role for primary care in Europe. Health Policy, 120(5), 495-508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.03.012

Official Gazette of the Hellenic Republic (2016), Law 4368: Measures to speed up government work and other provisions, National Printing Office, 2016 (in Greek), from https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/104200/127009/F-550014472/GRC104200%20Grk.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). Health for everyone? Social inequalities in health and health systems, OECD health policy studies. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/3c8385d0-en

Padovese, V., Egidi, A. M., MelilloFenech, T., Podda Connor, M., Didero, D., Costanzo, G., & Mirisola, C. (2014). Migration and determinants of health: Clinical epidemiological characteristics of migrants in Malta (2010–11). Journal of Public Health, 36(3), 368–374. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdt111

Pappa, E., Kontodimopoulos, N., Papadopoulos, A., Tountas, Y., & Niakas, D. (2013). Investigating unmet health needs in primary healthcare services in a representative sample of the Greek population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(5), 2017–2027. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10052017

Popovic, N., Terzic-Supic, Z., Simic, S., & Mladenovic, B. (2017). Predictors of unmet healthcare needs in Serbia; analysis based on EU-SILC data. PLoS One, 12(11), e0187866. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187866

Quintal, C., Lourenço, Ó., Ramos, L. M., & Antunes, M. (2019). No unmet needs without needs! Assessing the role of social capital using data from European social survey 2014. Health Policy, 123(8), 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.06.001

Rechel, B., Mladovsky, P., Devillé, W., Rijks, B., Petrova-Benedict, R., & McKee, M. (2011). Migration and health in the European Union, European observatory on health systems and policies series, from: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/161560/e96458.pdf. Accessed 18 Oct 2020

Rechel, B., Mladovsky, P., Ingleby, D., Mackenbach, J. P., & McKee, M. (2013). Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. The Lancet, 381(9873), 1235–1245. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62086-8

Rodney, A. M., & Hill, P. S. (2014). Achieving equity within universal health coverage: A narrative review of progress and resources for measuring success. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13, 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-014-0072-8

Ronksley, P. E., Sanmartin, C., Quan, H., Ravani, P., Tonelli, M., Manns, B., & Hemmelgarn, B. R. (2012). Association between chronic conditions and perceived unmet healthcare needs. Open Medicine, 6(2), e48–e58.

Sarría-Santamera, A., Hijas-Gómez, A. I., Carmona, R., & Gimeno-Feliú, L. A. (2016). A systematic review of the use of health services by immigrants and native populations. PUblic Health Reviews, 37, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-016-0042-3

Shao, S., Wang, M., Jin, G., Zhao, Y., Lu, X., & Du, J. (2018). Analysis of health service utilization of migrants in Beijing using Anderson health service utilization model. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 462. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3271-y

Simonet, D. (2010). Healthcare reforms and cost reduction strategies in Europe: The cases of Germany, UK, Switzerland, Italy and France. International Journal of Healthcare Quality Assurance, 23(5), 470–488. https://doi.org/10.1108/09526861011050510

Singh, G. K., Rodriguez-Lainz, A., & Kogan, M. D. (2013). Immigrant health inequalities in the United States: Use of eight major national data systems. The Scientific World Journal, 2013, 512313. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/512313

Solano, G., & Huddleston, T. (2020). Migrant integration policy index. Barcelona Center for International Affairs (CIDOB) and Migration Policy Group (MPG), from https://www.migpolgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Solano-Giacomo-Huddleston-Thomas-2020-Migrant-Integration-Policy-Index-2020.pdf

StataCorp. (2021). Stata statistical software: Release 17. StataCorp LLC.

Statistical Office of the European Union (Eurostat) (2019), How to apply for micro data?, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/203647/771732/How_to_apply_for_microdata_access.pdf. Accessed 30 Oct 2020

Suess, A., Ruiz Pérez, I., Ruiz Azarola, A., & March Cerdà, J. C. (2014). The right of access to healthcare for undocumented migrants: A revision of comparative analysis in the European context. The European Journal of Public Health, 24(5), 712–720. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku036

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 2019. UNHCR statistical yearbook 2015, from https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/country/59b294387/unhcr-statistical-yearbook-2015-15th-edition.html. Accessed 4 Aug 2020

Taglieri, F. M., Colucci, A., Barbina, D., Fanales-Belasio, E., & Luzi, A. M. (2013). Communication and cultural interaction in health promotion strategies to migrant populations in Italy: The cross-cultural phone counselling experience. Annali dell’Istituto superiore di sanità, 49, 138–142.

Thomson, S., Foubister, T., Mossialos, E., & World Health Organization. (2009). Financing healthcare in the European Union: Challenges and policy responses. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326415/9789289041652-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Thomson, S., Figueras, J., Evetovits, T., Jowett, M., Mladovsky, P., & Maresso, A. (2015). Economic crisis, health systems and health in Europe: Impact and implications for policy. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

Tognetti, M. (2015). Health inequalities: Access to services by immigrants in Italy. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 3(04), 8. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2015.34002

UNHCR (2019). Operational data portal. From https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179#_ga=2.252195593.1212904425.1622883720-290536606.1622883720

United Nations (UN) Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2020). International migration 2020 highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/452), from https://www.un.org/en/desa/international-migration-2020-highlights. Accessed 30 June 2021

UrbanosGarrido, R. M. (2020). Income-related inequalities in unmet dental care needs in Spain: Traces left by the Great Recession. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(207), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01317-x

Van Doorslaer, E., Wagstaff, A., Van der Burg, H., Christiansen, T., De Graeve, D., Duchesne, I., Gerdtham, U. G., Gerfin, M., Geurts, J., Gross, L., Hakkinen, U., John, J., Klavus, J., Leu, R. E., Nolan, B., O’Donnell, O., Propper, C., Puffer, F., Schellhorn, M., … Winkelhake, O. (2000). Equity in the delivery of health care in Europe and the US. Journal of Health Economics, 19(5), 553–583.

Van Doorslaer, E., Wagstaf, A., & Rutten, F. (1992). Equity in the finance and delivery of health care: An international perspective. Oxford University Press.

Vearey, J. (2016). Mobility, migration and generalised HIV epidemics: A focus on sub-Saharan Africa. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784714789.00030

Villadsen, S. F., Sievers, E., Andersen, A. N., Arntzen, A., Audard-Mariller, M., Martens, G., Ascher, H., & Hjern, A. (2010). Cross-country variation in stillbirth and neonatal mortality in offspring of Turkish migrants in northern Europe. European Journal of Public Health, 20(5), 530–535. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq004

Violini, L. (2015). Salute, sanità e Regioni: un quadro di crescente complessità tecnica, politica e finanziaria. Le Regioni, 43(5–6), 1019–1030.

Wagstaff, A., & Van Doorslaer, E. (2000). Equity in healthcare finance and delivery. Handbook of health economics, 1, part B,1803–1862. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0064(00)80047-5

Wagstaf, A., Bilger, M., Sajaia, Z., & Lokshin, M. (2011). Health equity and financial protection: Streamlined analysis with ADePT software. The World Bank.

Wendt, C. (2009). Mapping European healthcare systems: A comparative analysis of financing, service provision and access to healthcare. Journal of European Social Policy, 19(5), 432–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928709344247

World Health Organization. (2010). How health systems can address health inequities linked to migration and ethnicity. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhaguen, from https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/127526/e94497.pdf. Accessed 30 Oct 2020

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HF, JP-D and JP-J designed the analysis performed in this paper. JP-D analysed the individual data and performed the statistical analysis. Results were interpreted and discussed by all authors, and HF elaborated the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable (this paper uses secondary data; ethics approval and consent were obtained by the original EU-SILC-Eurostat).

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributions to Literature

• This study makes a positive contribution to the literature and its scant evidence on migrants’ access to healthcare in Europe.

• Our work provides insight into the individual barriers and institutional factors that contribute to migrants’ unmet healthcare needs in Europe.

• Our study is the first to draw comparisons across EU countries considering the disparities in health financing and the structure of the health system.

• This research contributes with an appropriate statistical approach to model the unmet need for healthcare.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fares, H., Domínguez, J.P. & Puig-Junoy, J. Differential Probability in Unmet Healthcare Needs Among Migrants in Four European Countries. Int. Migration & Integration 24, 1523–1546 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-023-01024-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-023-01024-w