Abstract

Access to public health has been, is, and will be a necessary right for any person in the world, motivating the proposal of universalist approaches as the best way to provide this service. However, we know that universalism is limited, at best, when it concerns immigrants. In this article, we focus on Costa Rica’s and Uruguay’s health systems, generally acknowledged as Latin America’s most universal, to argue that there are important barriers that limit immigrants’ access to public health insurance and health care. Applying a model based on the work by Niedzwiecki and Voorend (2019) that allows us to disaggregate the barriers to access into legal, institutional, de facto, and agency barriers, our analysis shows that migration and social policy interact to create barriers of different magnitudes, often conditioning healthcare access on migratory status, formal employment, and/or purchasing power. These limitations to universal social protection create important vulnerabilities, not only for the immigrants involved, but also for the health systems, and therefore for public health, highlighting the limitations of universalism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Access to health care is a human right and the recent convulsive health crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of universal access to social protection schemes. Collectively funded, universal, and solidary state services have shown to be more effective in providing effective social protection (World Health Organization et al., 2018; Carroll & Frakt, 2017). However, as the recent pandemic has painfully laid bare, actual access to health services has been far from universal in most countries in Latin America (Enríquez & Sáenz, 2021; Filgueira et al., 2020; Martich, 2021).

One particularly vulnerable population across the continent are immigrants (Carrasco & Suárez, 2020). Right before the pandemic, the movement of people from one country to another was at a record high. Over 250 million live in a country different from the one they were born. In Latin America, the number of immigrants in 2020 reached 42.9 million, accounting for 15.3% of the immigrant population worldwide (ICMPD, 2021). Where global immigrants represent 3% of the population, in Latin America this is 6%, and in Central America 12% (United Nations, 2020). In addition, 72% of these migratory movements are intra-regional, that is, from one Latin American country to another.

As a region intricately entangled with migration flows, states face challenges to ensure their protection and integration, in particular into their often already strained healthcare systems. In their response to this challenge, governments have generally not given high priority to ensuring health coverage of their immigrant populations (Voorend, 2019; World Health Organization, 2021), even though immigrants tend to live in worse conditions than nationals—many work in risky jobs, and have less access to health care, pensions, and formal education (Maldonado et al., 2018).

Therefore, this paper asks to what extent do states in Latin America protect immigrants from health risks? Do immigrants have differential access to basic health services compared with nationals in Latin America? In this article, expanding on a conceptual-methodological tool originally proposed by Niedzwiecki and Voorend (2019) to analyze barriers to access to social policy, we analyze immigrants’ access to health care in two of Latin America’s most universal and long-standing social protection systems: Costa Rica and Uruguay. While their relatively generous health systems may generate the expectation that coverage might be extended to immigrants, our analysis shows that there are important barriers to access in both countries, despite very different migration scenarios (Costa Rica as a consolidated destination country, and Uruguay as a relatively new destination country).

Following Niedzwiecki and Voorend (2019), we differentiate between legal, institutional, de facto, and agency barriers to understand the mechanisms of exclusion from social policy. Using a novel conceptual-methodological approach to analyze the breakdown of social exclusion, understood as a process of obstruction induced by structural and institutional factors or deliberate agency by individual actors (Fischer, 2011), we argue that barriers to social policy for immigrants can be written into policies or become evident at the moment of implementing those programs. More specifically, exclusion can occur at the moment of policy design (by legal and de facto barriers) or at the moment of its implementation (by institutional and agency barriers).

In the following section, the literature is briefly reviewed after which our conceptual-methodological approach is further explained. In the “Methodological and Conceptual Considerations” section, the health systems and migration contexts of Costa Rica and Uruguay are contextualized. In the “Public Health Systems and Migration in Costa Rica and Uruguay” section, we present our analysis, and “Access and Barriers to Health Care for Immigrants in Costa Rica and Uruguay” provides final reflections, including a discussion on how differentiated access to health care in Latin America has its roots in the analyzed barriers, proposing and inviting the application of this type of analysis to identify the main bottlenecks to universalism in Latin America’s social policy.

Debates and Theory

Despite the unprecedented high number of immigrants in the world, and their apparent and increasing vulnerabilities, the literature has not kept up with events on the ground, particularly in Latin America. Three bodies of literature are of special interest, however, in the study of the dynamics of migration and social protection.

First, previous scholarships on welfare states in the USA and Europe have analyzed the incorporation (or lack thereof) of immigrants to the welfare state, as part of its population groups to be covered and in light of its broad capacity to aspire to a universal social protection system (Fox, 2012; Carmel et al., 2012).Footnote 1 It analyzes, for the most part, the design of policies and eligibility criteria, as well as actual coverage and effects of social protection (Garay, 2016; Huber & Stephens, 2012; Pribble, 2011). However, Latin American States have shown less institutional capacity to offer sufficient, universal social protection. Therefore, the literature from Latin America has focused on the constellation of state, market, and informal/family practices, proposing the concept of welfare regimes. There is considerable variation in these constellations across Latin America, and their capacity to provide social protection (Martínez Franzoni & Sánchez Ancochea, 2016; Noy, 2013). However, this welfare regimes literature pays little attention to immigrants, with noticeable exceptions (Maldonado et al., 2018; Noy & Voorend, 2016; Voorend, 2019).

Some important lessons from the literature that does link migrants with welfare regimes are that there may be substantial differences in access to social protection through the State, the market, and informal networks between nationals and immigrants. Formal entitlements to social policy do not always translate into de facto access to social services for immigrants. Pivotal factors in explaining the discrepancy between rights and access are migratory status (Voorend, 2019), institutions’ inventiveness in circumventing inclusionary laws (Noy & Voorend, 2016; Voorend, 2019), and xenophobic public opinions, often based on incorrect or imprecise information on the incidence of immigrants in public services and its financial implications, which may lead to rejections at the social service counter (Rangel, 2020; Rivero, 2019). Noy and Voorend (2016) conclude that the variation in the extension of social rights depends on the interaction between migration and social policy, the structure and organization of the health system, and regional and international regulatory frameworks.

More recently, the welfare regimes literature has had a special interest in the expansion of social policy during the last decade in Latin America (Antía, 2018; Garay, 2016; Jakubiak, 2017). This literature focuses on the factors that may explain why some countries have turned to more inclusionary social policy, expanding coverage and benefits, while others have lagged in this regard (Niedzwiecki, 2018; Ubasart-González & Minteguiaga, 2017). However, again, immigrant populations are not specifically included in these analyses.

Second, the international migration literature is ahead in engaging with inclusion and exclusion of immigrants, focusing on when, how, and why states grant immigrants social rights, how this is influenced by migration policy, and different types of welfare and incorporation regimes (see, for example, Harell et al., 2017; Lucassen, 2016). This literature has studied the granting of social rights to immigrant populations (Joppke, 2012; van Hooren, 2011), and has analyzed comparatively the differences in welfare (poverty, employment, and social benefits) between immigrant and national populations (Castles & Miller, 2014; Carmel et al., 2012), noting variations across regimes with respect to the integration of immigrants (Castles & Miller, 2014; Freeman & Mirilovic, 2016). These studies, however, focus predominantly on the formal recognition of rights to immigrants and not on actual access to social services (Antía, 2018; Voorend & Alvarado, 2021b), with notable exceptions such as the literature on social mobility which points to the fact that migratory movements mean a change in the social class of immigrants (usually a downgrade), which should be understood as an explanatory factor for their possibilities of accessing social protection and health care (Mendoza et al., 2018; Simandan, 2018). However, in general, the literature on international migration has largely excluded Latin America as a region of study. Studies of migration in Latin America, in turn, have not paid attention to immigrants’ social protection in a systematic and comparative way and have been mostly focused on individual countries as opposed to a comparative perspective (Cabieses & Oyarte, 2020). In particular, this literature has hardly interacted with the Latin American welfare regimes literature, with some notable exceptions (Maldonado et al., 2018; Noy & Voorend, 2016; Voorend, 2019).

Finally, the transnational social protection literature has placed emphasis on the interconnections between (transnational) forms of formal and informal social protection of immigrants. Social protection is understood broadly as the policies, programs, people, organizations, and institutions that provide and protect people (Levitt et al., 2017), including social policy, or what several studies call formal (or state) social protection (Barglowski et al., 2015; Faist & Bilecen, 2015). This literature focuses on the mobility of people between countries with different state capacities and analyzes how this may imply limitations in their access to formal social protection, due to the requirements for access to social protection programs, such as having residency or citizenship status (Dobbs & Levitt, 2017; Faist, 2017; Levitt et al., 2017; Parella & Speroni, 2018). As such, informal social protection mechanisms come to the forefront, many of which may have a transnational character; i.e., they transcend State borders. For Latin America, this literature is incipient, but highlights the importance of focusing on diverse informal mechanisms of social protection (Salazar & Voorend, 2019; Voorend & Alvarado, 2021b). This paper finds itself somewhere on the frontiers of these bodies of literature. Like the international migration literature, it focuses on formal social protection, but adopts a comparative lens to account for variation in welfare regime types.

Methodological and Conceptual Considerations

The original research from which this paper derives was an exploratory study of immigrants’ inclusion to and exclusion from social policy in different Latin American countries. In this article, we focus specifically on healthcare services as one of the first efforts to apply this analytical framework. Methodologically, document analysis was applied to laws, regulations, and institutional norms that regulate access to these services. The analysis focused on eligibility criteria, and the mechanisms that stipulate how and to what extent immigrants are included or excluded. Furthermore, semi-structured interviews with key representatives of the institutions providing these services allowed us to further our understanding of the barriers to health care.Footnote 2

To identify the inclusion/exclusion of immigrants, conceptually we adapt a definition of social exclusion proposed by Fischer (2011) who defines exclusion as a process of obstruction or repulsion. The focus is on the mechanisms that cause exclusion, rather than the result of being excluded. Such processes can be induced by structural, institutional, or agency mechanisms, and may be intentional or not. Like Fischer, we are interested both in the outcome of exclusion (do immigrants have access or not?) and the forms in which this outcome is shaped (how are immigrants excluded?). However, unlike Fischer, we follow Niedzwiecki and Voorend (2019) and decide to speak of barriers to access, instead of mechanisms of exclusion, because barriers better represent the idea that obstacles can nonetheless be jumped. In other words, immigrants may be ultimately able to access a given transfer or service despite the barriers encountered. The process will certainly be harder than for a citizen because of the existence of those barriers (Cabieses & Oyarte, 2020).

Four barriers to access are identified, which arise at either the design or the implementation stages of social policies. When a policy is designed, it can exclude immigrants by making a legal distinction between citizens and noncitizens or by incorporating requirements in the law that de facto make it very difficult for most noncitizens to access. At the implementation phase, policies can create exclusion when the institution or people (agency) in charge of the service provision further define conditions for access.

First, a legal barrier refers to an explicit form of leaving out noncitizens from a transfer of service that is stated in a law or a policy document. A good example would be when the law states that irregular immigrants are not eligible to access a particular social assistance policy. Second, de facto barriers arise when a condition for accessing a social benefit has different implications for immigrants and nationals, making access difficult in practice. That is, the law states no explicit exclusion of immigrants, and all conditions for access apply equally to nationals and immigrants. However, the implications of these requisites affect both populations differently. A good example is the minimum number of contributions required in many pension systems. While this applies to all, for immigrants who are typically overrepresented in the informal sector and often have lived in the country for a shorter time than citizens, reaching that number of minimum contributions might be much more difficult than for nationals. The result is that many immigrants do not access pensions in their host societies, even though there might be no legal barrier to access.

On the other hand, other barriers arise during policy implementation. Institutional barriers are not stated in the law but are explicitly determined by the institution in charge of providing a service or transfer. This is possible when the institution has some degree of autonomy regarding the eligibility criteria, for example, if a policy does not include a national ID requirement in its law, but the institution requires a valid ID for access, excluding undocumented immigrants. Barriers of agency, in turn, are the hardest to detect, as they take place at the moment of interaction between the service provider and the recipient. In the day-to-day counter interactions, it is possible that a receptionist, a doctor, or a nurse, for instance, asks for a national ID to access health services, even if this is not specified in the law or by the institution. Since 2016, For example, Chilean law accepts passports and foreign IDs as a valid identification for enrolling in the public health system, yet especially undocumented immigrants are sometimes denied access due to misinformation or discriminatory practices by healthcare providers (Cabieses et al., 2017). Similar accounts were documented in Costa Rica (Voorend, 2019).

Finally, the barriers are classified into four levels, depending on how challenging they are to surmount: inclusion (no barriers to enrollment in the health system), low barriers (that can be overcome with relative ease), high barriers (that are difficult to overcome, but do not imply total exclusion), and exclusion (which represent unsurmountable barriers). The lower the barrier, the more inclusive the social policy, and vice versa, the higher the barrier, the more exclusive the social policy.

In the analysis carried out for this article, we focus on health care. This decision is motivated by the fact that health care is the one social policy that, unlike education or pensions, is required through the whole span of one’s life. Also, in contrast with transfers, it is required by everyone, irrespective of income, and as it implies a physical interaction with the social service provision, it is in health care the presence of immigrants is most visible, and therefore their claim to access most polemic (Voorend, 2019). Our focus is on immigrants’ access to the Costa Rican and Uruguayan public health systems. In both countries, broadly, there are several ways to access the health system, which can be summarized in two paths: through a contributory pay-as-you-go system in which the State taxes income/wages (typically one part to the employer, and another to the employee), or through a non-contributory affiliation for which a person may qualify if they fall below a certain income level. In the latter case, the State pays for the cost of health care.

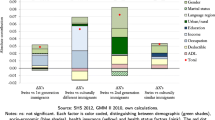

As the results will show below, the conceptual-methodological tool, based on Niedzwiecki and Voorend (2019), allows to pinpoint where barriers to access to social policy arise, and to what extent they exclude a specific population, in this case immigrants. However, certain limitations deserve mention. Our analysis focuses on migratory status to differentiate the population, but ignores to a large extent possible variations by gender, age, level of schooling, etc. This limitation relates more to the scope of this article, than the usefulness of the tool, because it does allow for this type of differentiated analysis. Another limitation relates to the agency barriers, concerning cases in which access to health care is limited through discrimination. These barriers are often subtle, extremely varied, and hard to detect. Also, while there is anecdotal and qualitative evidence that discriminatory practices take place, such evidence is often not generalizable, not found by quantitative studies, or not sufficiently researched to determine its scope (Voorend, Bedi and Sura-Fonseca, 2021). Further research would be welcome to investigate the extent to which discriminatory practices limit immigrants’ access to social policy.

Public Health Systems and Migration in Costa Rica and Uruguay

Before presenting our analysis, this section provides a general overview of the public health systems and general migration dynamics in Costa Rica and Uruguay (Table 1).

Costa Rica

Costa Rica has a long-standing, universal, and solidary health system, with a large public sector and a growing private sector (Cecchini et al., 2014; OECD, 2017). Its flagship institution, the Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social (Costa Rican Social Security Fund) (CCSS), was created in 1941, and is the monopoly public institution in charge of social security in Costa Rica and manages the provision of public health care. The CCSS relies on tripartite financing (employers, employees, and the State) and manages Costa Rica’s public health insurance scheme, called the Sickness and Maternity Insurance (Seguro de Enfermedad y Maternidad (SEM)), which provides health insurance coverage for between 87 and 94% of the population (Izarra & Delgado, 2020; OPS, 2019). The country presents an internationally acclaimed story of “health without wealth” (Noy, 2012; Noy & Voorend, 2016).

The SEM has four different points of entry, but once a person acquires an insurance, he or she has the exact same access to all the services offered in the public healthcare system. The system’s four main entry points are largely contributive, but there are also non-contributive health insurance types. First, affiliation is possible as salaried and independent workers, financed by contributions by the employer (9.25% of the salary), the worker (5.5%), and the Costa Rican State (1.0%). Second, there are affiliations for self-employed and other persons who voluntarily affiliate. They contribute 9.25% of the reference income for their profession, while the State contributes 1.25% (Article 33, Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica, 1997). Third, pensioners who contributed to the health system continue to receive a health insurance. These three modalities all include the possibility of affiliating economically dependent family members, through the family insurance.

Finally, there is an insurance by the State, which is a non-contributory insurance for people who fall under the poverty line. This applies to approximately 12.7% of the total insured population (Arce Ramírez, 2020), and implies a health insurance extension based on a socio-economic study. This group also comprises all children and pregnant women, to whom this health insurance is always extended, irrespective of whether they were previously affiliated to the CCSS. In case of emergencies, uninsured people are able to use hospitals and public health facilities, despite not counting on a health insurance, although they may be charged for these services later (Unger et al., 2008).

Since the austerity measures of the 1980s, the country’s healthcare system has faced great pressures which have affected its robustness (OECD, 2017; Quesada-Yamasaki, 2020; Sánchez-Ancochea & Martínez-Franzzoni, 2013). While the effects are only subtly visible on output indicators (OECD, 2020; Rojas, 2020), the growth of the private sector is apparent; private health spending increased from 23 to 33% between 2000 and 2009 (Sánchez-Ancochea & Martínez-Franzzoni, 2013), as well as the general dissatisfaction with public health services (Dobles et al., 2013). More recently, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and general mismanagement (MIDEPLAN, 2016; Pacheco et al., 2020), the financial sustainability of the CCSS was seriously compromised (OPS/OMS, 2013; Carrillo-Lara et al., 2011), leading to more austerity measures.

In this context of erosion of the public healthcare system, the inclusion of immigrants in health services is a thorny issue. Costa Rica is one of Latin America’s most important immigrant-receiving countries, with about 10.2% of the population born elsewhere. Most come from Nicaragua (70.98%), while Colombia and El Salvador migrants account for about 10% (Morales-Ramos, 2018). The contexts of violence in other Central American countries and natural disasters marked the beginning of important contemporary migratory flows in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. In the 1990s, labor migration dominated, especially due to the lack of economic opportunities in neighboring Nicaragua. More recently, migration flows have diversified, with Central Americans escaping violence in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala (Salazar & Voorend, 2019), and Venezuelans (since 2016) and Nicaraguans (since 2018) escaping political unrest (Fundación Arias, 2019; Voorend, Guilarte, et al., In press). Costa Rica is also a country of transition to the USA for other migratory groups, for example, from countries in Africa (Villalobos Torres, 2018).

Migration is legally regulated under Law 8764, which was approved in August 2009 and came into effect in March 2010 and is implemented by the General Directorate for Migration and Foreigners (Dirección General de Migración y Extranjería (DGME)). On paper, the law comprises a serious commitment to an integrated approach to migration policy, with emphasis on “principles of respect for human rights; cultural diversity; solidarity; and gender equity” (Art. 3, Ley General de Migración y Extranjería. No. 8764., 2009). While an improvement in comparison to the highly punitive previous law, which emphasized immigration control (Fouratt, 2014; Kron, 2011; Lopez, 2012), the current Law has received criticism for the vague definition of integration and the absence of a defined regulatory framework to ensure implementation (Voorend, 2014), while still giving a lot of centralities to security issues and handing the Migration Police great authority (Kron, 2011). Also, it implies high costs for the regularization process, complicating immigrant access to social services (Noy & Voorend, 2016).

Uruguay

Uruguay, like Costa Rica, has a long-standing, strong, and universal social security system, which, despite going through the dictatorial period of the 1970s, has maintained the foundations of its social security system with a mixed public–private model since the 1960s (Banco de Previsión Social, n.d.; Bertoni, 2020). The system is divided in an approximate 50/50 ratio between a public sector, led by the State Health Services Administration (Administración de los Servicios de Salud del Estado (ASSE)) and an important private sector organized under the Institutions of Collective Medical Assistance (Instituciones de Asistencia Médica Colectiva (IAMC)).

The public system, founded in 1935 through the creation of the Ministry of Public Health to initially assist poor populations, has undergone several changes over the years, including the addition in 1987 of the ASSE as the main state program provider of comprehensive health care in the public system of Uruguay (Law No. 18.161). Other changes were less expansionary, such as the closure of more than 15 health institutions (covering over 170,000 users) following the country’s economic crises during the 1990s (Aran, 2011; Barot, 2016; PAHO, 2015). The private branch emerged from efforts by immigrant groups that were generating “relief societies, mutual associations, which provided the predominant health care in the private sector, with a pre-payment and non-profit system, under the principles of solidarity and mutual aid” (PAHO, 2015: p. 10., Own translation). Currently, ASSE covers between 30 and 40% of the population (Ministerio de Salud Pública, n.d.).Footnote 3

In 2005, the health system was reformed to create the National Integrated Health System (SNIS). The objective was to achieve the articulation in comprehensive networks of public and private services, to expand basic coverage for low-income people without social insurance, and to define a single administrator of health services (Oreggioni, 2015; Sollazzo & Berterretche, 2011). It also created the National Health Insurance (Law 18,211), the creation of the National Health Fund—FONASA as the single administrator of health services (Law 18,131), and the decentralization of state health services (Law 18,161).

With the reform in place, people have the possibility of affiliating to the public entity (ASSE) or to one of the private providers (IAMC). Whichever the choice, the main entries to the system are the same: affiliation as dependent and independent workers, contributing between 3 and 6% of their salaries depending on the level of income and whether they affiliate family members, plus a 5% employer’s contribution when applicable. Family members can be affiliated, which increases the contribution percentages. Contribution and family coverage payments vary according to whether the main affiliate’s income is above or below a national minimum income reference.Footnote 4 There is also a non-contributory entry mode, which is covered by the State and focuses on vulnerable populations: homeless people, pregnant women, and children (Barot, 2016; Oreggioni, 2015).

In this context, of a strong healthcare system with high public healthcare spending (Lizardy, 2021), there is an emerging challenge of incorporating a growing immigrant population. Over the last decades, Uruguay has become an important migration destination country. Currently, approximately 3.1% of the total population was born abroad, coming mainly from Argentina and Brazil, Spain, and Italy (IOM, 2011). This immigrant population is generally older, with a higher educational profile and greater purchasing power than that of Costa Rica. However, these migratory trends seem to be changing in the context of economic growth in the early 2000s, with the arrival of younger people of diverse origins, including Chile, Paraguay, and Peru (MIDES, 2017; OIM Uruguay, 2011).

This migratory context is regulated by Law No. 18250, which came into force in January 2008, repealing a long-standing law dating back to the 1930s. It establishes the National Migration Board (Junta Nacional de Migración) as an advisory and coordinating body of migration policies of the Executive Branch (Law 18,250, Art. 24). The current law has been highlighted as an instrument inspired by the defense of human rights that ensures the foreign population equal conditions with the Uruguayan national population in areas such as access to health, labor, social security, housing, and education (MIDES, 2017; Ministerio del Interior, n.d.; Psetizki, 2010). The provisions of the Law are regulated by Decree 394/2009, establishing mechanisms to regulate the residence, access to health, education, work, and social security of immigrants. Likewise, the presence of an agreement signed with the Mercosur countries (Decree 312/015) allows to expedite the residence of people coming from those countries as well as their families. This new regulation is considered progress in migratory matters, which nevertheless has been criticized for weak inter-institutional collaboration in migratory matters and for being disconnected with immigrant realities (Facal, 2017).

Access and Barriers to Health Care for Immigrants in Costa Rica and Uruguay

This section presents our analysis of the barriers to access for immigrants in the public health systems of Costa Rica and Uruguay. We focus on the legal and de facto barriers that occur at the level of policy design, and the institutional and agency barriers that occur at the moment of policy implementation.

Three important considerations are of order. First, barriers, especially when they are low barriers, do not automatically imply exclusion, and may be overcome. Second, it is crucial to distinguish between different migratory status of (ir)regularity, because the barriers that the different groups face are very different. Third, there are different types of immigration which imply different levels of access to social policy. We focus on the most common of these: labor immigration. Based on these considerations, the analysis identifies the existence of barriers (yes or no) and the level of barriers identified (none, low, high, exclusion) for different groups of immigrants, based on migratory status.Footnote 5 A distinction is made between naturalized immigrants (who obtained the nationality of the host country), permanent and temporary residents (with a residence permit emitted by the host country), irregular immigrants (without a migration document emitted by the host country, but who do have some official document of identification from their home country), and undocumented immigrants (without documentation either from their host country or their country of origin). The analysis applies to the contributory and non-contributory schemes for accessing public health insurance.Footnote 6

Costa Rica

In Costa Rica, access to health care is strongly conditioned by migratory status (Voorend, 2019). In Table 2, the types of barriers to the contributory and non-contributory health systems are shown by migratory status. The analysis presented includes the contributory public health insurance for salaried or self-employed workers, the voluntary insurance, and the family insurance. Denizens (naturalized and permanent or temporary residents) do not encounter any legal barriers in policy design. The law explicitly requires persons to be legal residents to enroll in health insurance, thereby excluding irregular and undocumented immigrants (Art. 13, Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica, 1997).Footnote 7 On top of this legal barrier, the CCSS reaffirms that foreigners must present a national or residence ID, or at least a work permit indicating that the person is in the process of regularization (CCSS, n.d.-b).Footnote 8 The process is the same for family members, who must present their Costa Rican ID or residency documents.

Thus, besides the regular status requirement, Costa Rica’s law stipulates the exact same conditions for access to the health system for nationals and immigrants: having a health insurance (Noy & Voorend, 2016; Voorend, 2019). Regular immigrants, at least legally, have access to the health system, while irregular and undocumented immigrants are excluded. However, the interplay of migration and social policy in Costa Rica makes the regularization process complicated. In order to access health insurance, one requirement is to have a regular migratory status in the country. However, to obtain such a status, it is necessary to have a health insurance. This Catch-22 situation involves immigrants navigating two parallel processes. Two Constitutional Court sentences have resolved this situation in theory, dictating that the DGME should give a temporary permit while the CCSS emits a health insurance (Voorend, 2019). However, in practice, immigrants still face this Catch-22 situation which represents a high barrier for irregular and undocumented immigrants to access this insurance.

There are also de facto barriers to access, which arise from the fact that health insurance implies a cost for enrollment and builds on the assumption of employment in the formal sector. While informal jobs are not uncommon for the national population, a larger share of immigrants in the country works in the informal sector (about 60%) of the economy (Morales-Ramos, 2018; OIT, 2016; Voorend, Alvarado, et al., 2021; Voorend, Guilarte, et al., 2021). In practice, this makes immigrants’ access to insurance as salaried workers more difficult, and implies that, if they are to be insured, they often must resort to voluntary insurance. This, again, implies a cost, of about 9–15% of the estimated wage, to be paid by the worker (CCSS, n.d.-a). For an unskilled person earning a minimum wage of about US $570, this implies between US $50 and 85 per month, while the requisites for a prolonged regularized stay in Costa Rica add up to between US $370 and US $800 (Voorend, 2019). To this, the substantial costs of issuing and renewing residency documents needed for sustaining the health insurance must be added (Noy & Voorend, 2016). These high costs are classified as a high barrier for all immigrant groups, except for the naturalized foreigners.

Finally, with regard to agency barriers, cases of abuse and bad attention at healthcare services have been reported from interviews and news reports (Voorend, 2019; El Mundo CR, 2018; Rodríguez, 2013). Anecdotal evidence exists of discriminatory attitudes and xenophobia towards the immigrant population, especially from Nicaragua (Dobles et al., 2013; Fouratt, 2014; Voorend, 2019). Such attitudes may lead to exclusion, and unpleasant experiences depending on the counter clerk at the counter.

The non-contributory health insurance is composed of three distinct sub-branches: the inclusion of adults below the poverty line (which we can call Assumption of State Responsibility Insurance), as well as the universal inclusion of pregnant women and children (Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica, 1997). For these non-contributory health insurance entries, the de facto and institutional barriers change, while legally maintaining the same exclusion of non-resident immigrants and similar agency barriers.Footnote 9 Important institutional barriers are presented due to the fact that, even though the CCSS institutionally stipulates as a requisite having to present a Costa Rican ID or a residence card emitted by migration authorities (besides a sworn statement and an application form for State Assurance Benefits), it adds that foreigners must present these same regular migratory ID documents for all the members of the family nucleus older than 18 years old (CCSS, n.d.-a).Footnote 10 This means a (low) barrier for denizens, because they depend on their relatives being able to present the proper documentation as well. Obtaining and renewing this documentation are expensive (Voorend, 2019), which additionally to the institutional barrier represents a de facto barrier. In practice, immigrants are overrepresented among the lower income groups in Costa Rica (Voorend, Alvarado, et al., 2021; Voorend, Guilarte, et al., 2021).

Another low de facto barrier exists, as the non-contributory insurance implies that beneficiaries have asked for institutional support. This is generally less common among immigrants, because in practice they are often not aware of this and also it involves putting their information in public institutional hands, which is sometimes misinterpreted as a threat for them as immigrants (even if they have a regular status) (González and Horbaty, n.d.; Acuña, 2005). Also, the socio-economic studies necessary for eligibility are considered complex and bureaucratic, which often deters immigrants from seeking access (Cabieses & Oyarte, 2020; Noy & Voorend, 2016).

Uruguay

In contrast with Costa Rica, Uruguay exhibits greater inclusiveness from the legal point of view for all immigrant population groups (see Table 3), although there are some institutional and de facto barriers to immigrants’ access to health care. The absence of legal barriers is notable in Uruguay’s Integrated Health System Law which guarantees universal access to health insurance (Ley del Sistema Nacional Integrado de Salud., 2007),Footnote 11 while the Migration Law goes further and indicates that any immigrant who can prove his or her identity, with a document issued by their country of origin or by a third country, has access to health insurance. Even if no such document is available, it can be replaced with an affidavit (Ley de Migración., 2007).Footnote 12 This, in legal terms, allows for unrestricted access to the healthcare system, irrespective of migratory status.

However, we encountered an important institutional barrier. According to ASSE, the presentation of a valid ID is requested as an affiliation requirement and, in contrast with the Law, it does not enable the opportunity to present an affidavit if documentation is missing for non-resident immigrants (or immigrants with the residency process underway) (ASSE, n.d.). Therefore, undocumented immigrants are excluded institutionally. Also, the institution clarifies, on its website, that affiliation of non-resident foreigners only applies to those persons who have a regularization process underway. This implies that irregular immigrants have a high barrier to access health insurance, since they can only be enrolled if they first start the regularization process.

Another important institutional barrier is affiliation to ASSE’s health insurance. It is free of charge for Uruguayan nationals and immigrants with permanent or temporary residents who are under the income ceiling set by ASSE, but immigrants who are still in process of obtaining a residence permit are required to pay a membership fee.Footnote 13 This monetary differentiation represents a high barrier to access health insurance for irregular immigrants.Footnote 14

On the other hand, there are several de facto barriers to healthcare access. First, in the case of self-employed workers, like in Costa Rica, the full payment of contributions to the system (regardless of the migratory group) falls entirely on the direct savings of the individual, since there is no employer who contributes to this quota. Given especially recent immigrants’ larger incorporation in informal labor activities (Prieto et al., 2016), the costs associated with healthcare insurance can represent higher barriers for immigrants than for nationalsFootnote 15 (ASSE, n.d.). Second, there is an additional de facto barrier to access family insurance, as documents such as a birth certificate (in the case of children) or a marriage certificate (for spouses) are required to be presented by the affiliated worker. Like in Costa Rica, these legal documents can be more difficult to obtain for immigrants than for nationals, as they often involve traveling to their home countries. This was classified as a low barrier for denizens and residents, although the barrier is higher for irregular and undocumented immigrants, because their travel to and from their country of origin happens in irregular circumstances.

Finally, we did not find many reports on agency barriers in Uruguay. Although there are complaints of mistreatment at the time-of-service delivery in health facilities (Mourelle, 2021), and reports on cases of xenophobia in the country (López, 2020), no direct relationship between the two issues was found. In interviews with ASSE representatives, it was reiterated that usually the user complaints they receive do not indicate xenophobic attitudes. Further research is recommended on this issue.

On the other hand, with respect to non-contributory health insurance, like in Costa Rica, barriers to access are substantially lower. Legally, full inclusion is maintained for resident and non-resident immigrants, while institutionally, the presentation of an ID is requested, which excludes undocumented immigrants, and limits irregular immigrants to only the ones with open residency procedures (ASSE, n.d.). Finally, in general, there is a low de facto barrier for all groups, as ASSE requests the presentation of documents such as letters of shelter or refuge for homeless people or a salary receipt for all family members of pregnant women who require this insurance to demonstrate their lack of economic capacity to contribute to the system. These types of documents require additional effort for immigrants to apply for them.Footnote 16 Also, interested beneficiaries are required to seek out these institutions, which creates a certain fear among undocumented and irregular immigrants to be exposed to the migration authorities.

Final Reflections: Limited Protection in Contexts that Demand Universality?

This paper has elaborated and applied a conceptual-methodological tool, initially proposed by Niedzwiecki and Voorend (2019) for the study of the mechanisms of social exclusion. This tool proves useful to identify the barriers to access, in this case, to public health care. By operationalizing previous definitions of social exclusion that center on the process and mechanisms, instead of the outcomes, of exclusion, the tool has potential to be used in other settings, policy sectors, or other populations.

In the analysis provided here for migrants’ access to public health care in Costa Rica and Uruguay, it shows that, even in those Latin American countries characterized by a strong and institutionalized social policy system, there are significant barriers to immigrants’ access to public health, and that these barriers arise from policy design, or arise during the implementation phase. These barriers can be legal, with explicit barriers written in the laws, and which may arise from an interplay between migration law and social policy (Voorend, 2019). In Costa Rica, this happens through parallel (and somewhat paradoxical) requirements for immigration regularization and access to health insurance. In Uruguay, the Migration Law is more inclusive in terms of healthcare access, but the combination of the Social Security Law and ASSE’s implementation creates (institutional) barriers, nonetheless. In both countries, de facto barriers were found as well: the rules of the game are the same for nationals and immigrants but affect the latter differently.

During the implementation phase, the institutions in charge of healthcare provision may establish additional requirements, which turn into institutional barriers. This is the case in Uruguay, for example, where legal access to health care is, on paper, guaranteed, but the country’s healthcare institutions limit access with their own requirements. Finally, there are very subtle barriers, which are much more difficult to document, created during the interaction between the health service provider and the patient. Like Voorend (2019) argues for Costa Rica, the person working at the counter potentially has a big influence on whether an immigrant receives attention, and the quality of that attention.

In the countries analyzed for this paper, access is highly dependent on migratory status, thereby underscoring previous findings (Noy & Voorend, 2016; Rangel, 2020; Voorend, 2019), but also by the immigrant’s capacity to find employment in the formal economy. The breakdown of the analyzed barriers is useful because it allows for disaggregated analysis of the mechanisms that explain why and to what extent immigrants obtain access to health services in the host country, or not. As it was exposed, the absence of one type of barrier does not guarantee access. In Costa Rica, despite the health system’s high levels of coverage and high-quality services, there are important legal and institutional barriers that exclude irregular and undocumented immigrants from accessing a public health insurance, while the interplay between social and migration policy also creates additional (low) barriers, related to the costs of affiliation and regularization. In contrast, the Uruguayan law is more inclusive, but the additional requisites and fees established by the social security institutions show their autonomy to create barriers to inclusion.

Non-contributory health insurance schemes typically present fewer and lower barriers, although they also tend to exclude undocumented immigrants. However, in practice access is limited through the economic costs implied with affiliation processes, and the presentation of the required documentation (certificates, IDs, proof of income). We find that non-contributory schemes are also often present institutional and de facto barriers, which make enrollment usually more difficult or impossible to achieve for immigrant groups, especially irregular and undocumented immigrants.

In general, these barriers compromise the aspirations of universality in health systems, where affiliation is conditioned on residency status, monetary capacity, and access to formal employment. This study, then, highlights the crucial difference between the recognition of rights and actual access to social services.

In part, the literature already warned that in times of austerity and situations in which national health systems have trouble in extending coverage or providing quality services to the national population, the inclusion of immigrants is not a priority (Carrasco & Suárez, 2020; Voorend & Alvarado, 2021b; World Health Organization, 2021). The barriers to access are troubling in the sense that they limit universalism when coverage should include all. After all, many health threats, like the current COVID-19 virus, do not respect these barriers, and by not including immigrants in public health, health systems shoot themselves in the proverbial foot.

Notes

Specifically for Costa Rica and Uruguay, a total of six interviews were conducted with personnel from the healthcare agencies of these countries to discuss the access opportunities offered to immigrants and where the main obstacles might be.

In interviews with ASSE personnel, it was commented that this coverage could be as high as 50% of the total population.

The Benefits and Contributions Base (BPC) is an index used to calculate taxes, income, and social benefits. It replaces the use of a national minimum wage in Uruguay. It was created by Law 17,856 of 2004 and its value is updated every January 1, being for 2021 its value of $4,870. If the affiliate has an income level lower than 2.5 BPC, his contribution is 3% of his salary regardless of whether it covers family members or not, while contributors with income above the 2.5 BPC threshold have a contribution of 4.5%, in the case of not attributing coverage to another beneficiary, 6% in the case of attributing coverage to dependents under 18 years of age or for disabled persons over 18 years of age, and an additional 2% in the case of assigning coverage to a spouse (ASSE, n.d., own translation).

It is worth noting that the components of transversality should be further deepened in attributes on further analysis, including aspects such as gender, age, or sexual orientation. This is because, for example, an immigrant woman might face different barriers, especially of the agentive type, than a man, despite having the same migratory status.

As previously mentioned, these public health schemes operate as collective funds, where the employer contributes a certain percentage over wages, and the employee another percentage (the latter normally lower than the former). Within contributory schemes, there are typically pay-as-you-go schemes, which tax wages, or independent and voluntary schemes, which calculate the contributions from estimated or self-reported earnings. Also, family insurance falls under this category, where the contributor may include dependent family members in the insurance package. Non-contributory public health insurance, in contrast, implies that the person who receives health insurance does not pay with contributions over his or her wage/income. Instead, the costs are covered based on general contributions and other taxes.

Article 13, Health Insurance Regulation, 1997. Own Translation. A) Requirements for assignment or identification.

Foreign person of legal age: Present DIMEX (includes the categories of Refugee Applicant and Work Permit) or Passport in force and in good condition, as appropriate. When the foreigner is in the process of regularization and his/her identity document is expired, he/she must additionally present a resolution of approval of residence.

In order to be assigned an insurance number, you are required to present your residence card or the respective residence and work permit. Work permits for foreigners must be processed by the employers based on the regulations of the law, regardless of the type of job and the economic activity in which they are required. All foreign workers require a work permit, since in Costa Rica labor rights are guaranteed by the Political Constitution, the Labor Code, and other related laws. (…) With the permit, the employer or contractor has the duty to affiliate the worker to social security, represented by the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS) (CCSS, n.d., own translation).

Article 13, Health Insurance Regulation, Costa Rica, 1997. own translation.

In addition to the declared poverty status, the following must be met:

The presentation of the valid identification document; in the case of nationals the identity card, and in the case of foreigners the current residence card or administrative resolution issued by the General Directorate of Migration and Foreigners that indicates the approval of the migratory status of legal resident, this for all the members of the family nucleus older than 18 years old. In the case of foreign minors, a residency card, passport, or authenticated or apostilled proof of birth must be provided. (CCSS, n.d.-b, own translation).

Requirements.

Identification document in force and in good condition:

- Identity card or Minors’ Identification Card (TIM), in the case of nationals.

- In the case of foreigners: Current residence card or administrative resolution issued by the General Direction of Migration and Foreigners that indicates the approval of the migratory status of legal resident, this for all the members of the family nucleus older than 18 years old. In the case of foreign minors, it will be necessary to provide a residence card, passport, or authenticated or apostilled proof of birth.

2. Affidavit.

3. Application form for State Assurance Benefits. (CCSS, n.d.-b, own translation).

Law No. 18.211. Article 1.- This law regulates the right to health protection of all inhabitants residing in the country and establishes the modalities for their access to comprehensive health services. Its provisions are of public order and social interest.

Article 3º.- The following are guiding principles of the National Integrated Health System: (…).

c. The universal coverage, accessibility, and sustainability of the health services.

Law 18.250/2008: "Sect. 35—Without prejudice to the provisions of Sect. 49 of Law No. 18.211, the migratory irregularity shall not constitute an obstacle for the access to comprehensive health benefits through the entities comprising the National Integrated Health System, under the conditions provided for in the previous section of this Decree. In these cases, immigrants shall prove their identity before the health service provider in question with the document issued by the country of origin or by a third country in their possession. If they do not have any, they shall do so by means of a sworn statement. In the case of minors or disabled adults, the affidavit on identity shall be provided by the persons in whose care they are.".

Foreigners (with or without residency proceedings) and returnees to the country may affiliate to ASSE.

1) Foreigners (with residency in process) and without formal coverage may join ASSE, according to Law Nº 18.250; Decree Nº 394/09, Arts. 34 and 39 through a free affiliation. The validity of such procedure shall be subject to the date of the residency procedure.

Membership requirement: photocopy of identification document, proof of income, and proof of residence procedure.

Cost of assistance—tickets and orders: People with free affiliation are entitled to integral health care free of charge in any of ASSE’s health services. This means that they do not pay for orders or tickets, for any concept of their care.

2) Foreigners (without residency), spouse/legal spouse, and children without residency may affiliate to ASSE by paying an ASSE Quota, according to Decree Nº 394/09, Art. 37.

Membership requirement: photocopy of identification document.

Cost of assistance—tickets and orders: People with ASSE Quota affiliation are entitled to integral health care free of charge in any of the ASSE health services. This means that they do NOT pay orders or tickets, for any concept of their care. Those benefits that are not included in the National Plan of Integral Attention have the following attention policy.

Likewise for family insurance, there is an additional important particularity to note, in that affiliation can be done through two instances: the BPS or FONASA, both giving access to the same family health insurance provided by ASSE. However, in practice the BPS does not affiliate foreigners (only Uruguayan or naturalized) and therefore, the only viable option is to affiliate via FONASA.

Although there is an exception to the payment of affiliation fees if the person’s income is below an institutionally established ceiling, which attenuates the barrier (ASSE, n.d.). In the case of self-employed workers, there is a possibility that they do not have to contribute to the health insurance if their income is under a defined ceiling. If you exceed the income ceilings established for the free membership category or are affiliated with a private provider, the only way to join ASSE is to pay a monthly contribution.

This was confirmed in interviews with ASSE personnel. It was commented that these difficulties in obtaining these documents are not documented but that they are aware that in practice they can be a difficulty for immigrants.

References

Acuña, G. (2005). La Inmigración en Costa Rica: Dinámicas, Desarrollo y Desafíos. Proyecto Fondo OPEC-UNFPA. San José, Costa Rica.

Antía, F. (2018). Regímenes de política social en América Latina: Una revisión crítica de la literatura*. Revista Desafíos, 30(2). https://revistas.urosario.edu.co/xml/3596/359655844007/index.html. Accessed 14 June 2022

Aran, D & H. Laca. (2011). Sistema de salud de Uruguay. Revista Salud Pública México. https://www.scielosp.org/pdf/spm/v53s2/21.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Arce Ramírez, C. A. (2020). Financiamiento y cobertura del Seguro de Salud en Costa Rica: Desafíos de un modelo exitoso. Gestión En Salud y Seguridad Social, 1(1), 12–20.

Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica. (1997). Reglamento de Seguro de Salud. http://www.pgrweb.go.cr/scij/Busqueda/Normativa/Normas/nrm_texto_completo.aspx?param1=NRTC&nValor1=1&nValor2=43463&strTipM=TC. Accessed 14 June 2022

Asamblea Legislativa de Costa Rica (2009). Ley General de Migración y Extranjería. No. 8764. Costa Rica: Asamblea Legislativa. https://www.migracion.go.cr/Documentos%20compartidos/Leyes/Ley%20General%20de%20Migraci%C3%B3n%20y%20Extranjer%C3%ADa%208764.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

ASSE. (n.d.). ¿como me afilio? - ASSE. http://afiliaciones.asse.com.uy/web/guest/prestacion. Accessed 14 June 2022

Banco de Previsión Social. (n.d.). Evolución histórica. Banco de Previsión Social. https://www.bps.gub.uy/11626/evolucion-historica.html. Accessed 14 June 2022

Barglowski, K., Bilecen, B., & Amelina, A. (2015). Approaching transnational social protection: Methodological challenges and empirical applications: Approaching transnational social protection. Population, Space and Place, 21(3), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1935

Barot, P. (2016). Reforma de la salud en Uruguay: Avances y vacíos. (Tesis para optar por el grado de Licenciatura en Trabajo Social). Universidad de la República. https://www.colibri.udelar.edu.uy/jspui/bitstream/20.500.12008/21957/1/TTS_BarotCostasPatricia.pdf. Accesed 14 June 2022

Bertoni, A. (2020). La seguridad social desde la dictadura a la fecha. La diaria. https://ladiaria.com.uy/opinion/articulo/2020/12/la-seguridad-social-desde-la-dictadura-a-la-fecha/. Accessed 14 June 2022

Cabieses, B., & Oyarte, M. (2020). Acceso a salud en inmigrantes: Identificando brechas para la protección social en salud. Revista de Saúde Pública, 54. https://doi.org/10.11606/S1518-8787.2020054001501

Cabieses, B., Oyarte, M., & Delgado, I. (2017). Uso efectivo de servicios de salud por parte de migrantes internacionales y población local en Chile. In La migración internacional como determinante social de la salud en Chile: Evidencia y propuestas para políticas públicas (pp. 146–179). Universidad de Desarrollo.

Carmel, E., Cerami, A. & Papadopoulos, T. (2012). Migration and welfare in the New Europe: Social protection and the challenges of integration. Bristol: Bristol University Press

Carrasco, I., & Suárez, J. I. (2020). Migración internacional e inclusión en América Latina. Serie Políticas Sociales No. 231. Santiago: CEPAL. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/43947/1/S1800526_es.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Carrillo-Lara, R., Martínez Franzoni, J., Naranjo, F., & Sauma, P. (2011). Informe del equipo de especialistas nacionales nombrado para el análisis de la situación del seguro de salud de la CCSS. Recomendaciones para restablecer la sostenibilidad financiera del seguro de salud. San José: IIS-UCR. https://bibliotecavirtual.clacso.org.ar/Costa_Rica/iis-ucr/20120726043438/informe.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Carroll, A. E., & Frakt, A. (2017, September 18). The best health care system in the world: Which one would you pick? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/18/upshot/best-health-care-system-country-bracket.html, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/18/upshot/best-health-care-system-country-bracket.html. Accessed 14 June 2022

Castles, S., & Miller, M. J. (2014). The age of migration. International population. Movements in the modern world. In The age of migration: International population movements in the modern world (Fifth, pp. 1–18). Macmillan Education UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-26846-7_1. Accessed 14 June 2022

CCSS. (n.d.-a). Cátalogo de Trámites. CCSS - Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social. https://www.ccss.sa.cr/tramites. Accessed 3 Sept 2021

CCSS. (n.d.-b). Preguntas Frecuentes. CCSS - Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social. https://www.ccss.sa.cr/preguntas-frecuentes. Accessed 3 Sept 2021

Cecchini, S., Filgueira, F., & Robles, C. (2014). Social protection systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: A comparative perspective. Series Social Policy No. 202. Commission publication Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

datosmacro.com. (2019). Migrantes totales 2019 | datosmacro.com. https://datosmacro.expansion.com/demografia/migracion/emigracion. Accessed 10 Sept 2021

Dobbs, E., & Levitt, P. (2017). The missing link? The role of sub-national governance in transnational social protections. Oxford Development Studies, 45(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1271867

Dobles, I., Vargas, G., & Amador, K. (2013). Inmigrantes: Psicología, identidades y políticas públicas. La experiencia nicaragüense y colombiana en Costa Rica. San José: Editorial UCR.

El Mundo CR. (2018, 9th of april). Defensoría: CCSS debe garantizar atención prenatal a mujeres en estado de embarazo. https://www.elmundo.cr/costa-rica/defensoria-ccss-debe-garantizar-atencion-prenatal-a-mujeres-en-estado-de-embarazo/. Accessed 10 Sep 2021

Enríquez, A., & Sáenz, C. (2021). Primeras lecciones y desafíos de la pandemia de COVID-19 para los países del SICA. Serie Estudios y Perspectivas No. 189. México: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL).

Facal, S. (2017). Movimientos Migratorios en Uruguay. Un estudio a través del marco normativo. Observatorio Iberoamericano sobre Movilidad Humana, Migraciones y Desarrollo, OBIMID.

Faist, T. (2017). Transnational social protection in Europe: A social inequality perspective. Oxford Development Studies, 45(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1193128

Faist, T., & Bilecen, B. (2015). Social inequalities through the lens of social protection: Notes on the transnational social question: Social inequalities through the lens of social protection. Population, Space and Place, 21(3), 282–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1879

Filgueira, F., Galindo, L. M., Giambruno, C., & Blofield, M. (2020). América Latina ante la crisis del COVID-19: Vulnerabilidad socioeconómica y respuesta social. Serie Políticas Sociales, No. 238. México: Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL).

Fischer, A. M. (2011). Reconceiving social exclusion. Brooks World Poverty Institute. http://www.bwpi.manchester.ac.uk/resources/Working-Papers/bwpi-wp-14611.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Fouratt, C. (2014). “Those who come to do harm”: The framings of immigration problems in Costa Rican immigration law. International Migration Review, 144–180. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fimre.12073

Fox, C. (2012). Three worlds of relief: Race, immigration, and the American welfare state from the progressive era to the new deal. New Yersey: Princeton University Press.

Freeman, G. P., & Mirilovic, N. (2016). Handbook on migration and social policy. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing

Fundación Arias. (2019). De la represión al exilio: Nicaragüenses en Costa Rica. Caracterización sociodemográfica, organizaciones y agenda de apoyo. Fundación Arias para la Paz y el Progreso Humano. https://www.migrationportal.org/es/resource/represion-exilio-nicaraguenses-costa-rica-caracterizacion-sociodemografica-organizaciones-agenda-apoyo/. Accessed 14 June 2022

Garay, C. (2016). Social policy expansion in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316585405

González, H., & Horbaty, G. (n.d.). Nicaragua y Costa Rica: Migrantes enfrentan percepciones y políticas migratorias. https://ccp.ucr.ac.cr/noticias/migraif/pdf/horbaty.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Harell, A., Soroka, S., & Iyengar, S. (2017). Locus of control and anti-immigrant sentiment in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Political Psychology, 38(2), 245–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12338

Huber, E., & Stephens, J. (2012). Democracy and the left: Social policy and inequality in Latin America. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

International Labour Organization - ILO. (2016). La migración laboral en América Latina y el Caribe: Diagnóstico, estrategia y líneas de trabajo de la OIT en la región. International Labour Organization, Oficina Regional para América Latina y el Caribe.

International Center for Migration Program Development - ICMPD. (2021). Perspectivas de las migraciones en 2021 en Latinoamérica y el Caribe (LAC). Cinco aspectos a tener en cuenta en 2021. Tendencias y acontecimientos claves en la región. International Center for Migration Program Development. https://www.icmpd.org/file/download/51076/file/RMO_LAC_2021_ES_final.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

International Organization for Migration - IOM. (2011). Perfil Migratorio Uruguay. Organización Internacional para las Migraciones. Oficina Regional para América del Sur. Buenos Aires: IOM.

Izarra, L. G., & Delgado, R. G. M. (2020). Desarrollo en Centroamérica: Hacia una agenda de políticas sociales. Análisis comparado entre el Triángulo Norte y Costa Rica. Cuadernos Inter.c.a.mbio sobre Centroamérica y el Caribe, 17(2), e41765–e41765. https://doi.org/10.15517/c.a..v17i2.41765

Jakubiak, I. (2017). Migration and welfare systems – State of the art and research challenges. Central European Economic Journal, 1 https://doi.org/10.1515/ceej-2017-0004

Joppke, C. (2012). Citizenship and immigration. Ethnicities, Cambridge, Oxford, Boston, MA: Polity. pp.844–863. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796812449706

Kron, S. (2011). Gestión migratoria en Norte Y Centroamérica: Manifestaciones y contestaciones. Anuario de Estudios Centroamericanos, Vol. 37. San José, Costa Rica. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/152/15237016002.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Levitt, P., Viterna, J., Mueller, A., & Lloyd, C. (2017). Transnational social protection: Setting the agenda. Oxford Development Studies, 45(1), 2–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1239702

Poder Legislativo de la República de Uruguay (2007). Ley del Sistema Nacional Integrado de Salud., no. 18.211. https://www.paho.org/uru/dmdocuments/Ley18211SNIS.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Lizardy, G. (2021). Cómo Uruguay evitó el colapso de su sistema de salud pese a tener una de las peores tasas de muertes nuevas por covid-19. BBC News Mundo. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-57251662. Accessed 14 June 2022

López, A. (2020). Rinche Roodenburg: “En Uruguay hay racismo, xenofobia y discriminación.” Diario EL PAIS Uruguay. https://www.elpais.com.uy/domingo/rinche-roodenburg-uruguay-hay-racismo-xenofobia-discriminacion.html. Accessed 14 June 2022

Lopez, M. (2012). The incorporation of Nicaraguan temporary migrants into Costa Rica’s healthcare system: An opportunity for social equity? Electronic Theses and Disertations, 502. University of Windsor. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1501&context=etd. Accessed 14 June 2022

Lucassen, L. (2016). Migration, membership regimes and social policies: A view from global history. . In: Freeman, G. P., and Mirilovic, N. (eds) (2016). Handbook on migration and social policy. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing

Maldonado, C., Martínez, J., & Martínez, R. (2018). Proteccion social y migración. Una mirada desde las vulnerabilidades a lo largo del ciclo de la migración y de la vida de las personas. CEPAL, 120.

Martich, E. (2021, June 16). Salud y desigualdad: La pandemia reforzó lo que ya sabíamos | Nueva Sociedad. Nueva Sociedad | Democracia y Política En América Latina. https://nuso.org/articulo/salud-y-desigualdad-la-pandemia-reforzo-lo-que-ya-sabiamos/. Accessed 14 June 2022

Martínez Franzoni, J., & Sánchez Ancochea, D. (2016). The quest for universal social policy in the south: Actors, ideas and architectures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316410547

Mendoza, S., Armbrister, A. N., & Abraído-Lanza, A. F. (2018). Are you better off? Perceptions of social mobility and satisfaction with care among Latina immigrants in the U.S. Social Science & Medicine, 1982(219), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.014

Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica - MIDEPLAN. (2016). Costa Rica: Estado de las Pensiones. Régimen de Invalidez, Vejez y Muerte. Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica. Unidad de Análisis Prospectivo. https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/r37657.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Ministerio de Desarrollo Social - MIDES. (2017). Caracterización de las nuevas corrientes migratorias en Uruguay: Nuevos orígenes latinoamericanos: estudio de caso de las personas peruanas y dominicanas. Ministerio de Desarrollo Social - MIDES. (Universidad de la Repúbica Uruguay. https://monotributo.mides.gub.uy/innovaportal/file/76604/1/caracterizacion-de-las-nuevas-corrientes-migratorias-en-uruguay..pdf. Accessed 14 Sept 2021

Ministerio de Salud. (2018). Informe Cobertura Poblacional del SNIS según prestador. 22. https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-salud-publica/sites/ministerio-salud-publica/files/documentos/publicaciones/Informe%20Cobertura%20poblacional%20del%20SNIS%20seg%C3%BAn%20prestador%202018.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Ministerio de Salud Pública. (n.d.). Cobertura poblacional. Ministerio de Salud Pública. Retrieved from https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-salud-publica/tematica/cobertura-poblacional. Accessed 13 Sept 2021

Ministerio del Interior. (n.d.). Uruguay país modelo: Aquí se garantizan los derechos de los migrantes. Ministerio del Interior. Retrieved from https://www.minterior.gub.uy/index.php/2013-06-17-14-41-56/2012-11-13-13-08-52/78-noticias/ultimas-noticias/1859-uruguay-pais-modelo-aqui-se-garantizan-los-derechos-de-los-migrantes (Accessed: 10th of September, 2021).

Morales-Ramos, R. (2018). Inmigración y empleo en Costa Rica: Un análisis con perspectiva de género a partir de la encuesta continua de empleo. Economía y Sociedad, 23(54), 51–72. https://doi.org/10.15359/eys.23-54.5

Mourelle, I. (2021, June 10). Usuario denuncia carencias en Emergencia del hospital de Rivera | La Mañana. https://www.xn--lamaana-7za.uy/actualidad/usuario-denuncia-carencias-en-emergencia-del-hospital-de-rivera/. Accessed 14 June 2022

Nannestad, P. (2007). Immigration and welfare states: A survey of 15 years of research. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 512–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2006.08.007

Niedzwiecki, S. (2018). Uneven social policies: The politics of subnational variation in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Niedzwiecki, S., & Voorend, K. (2019). Barriers to social policy and immigration in Latin America. Fifth Southwest Workshop on Mixed Methods Research.

Noy, S. (2012). World Bank projects and targeting in the health sector in Argentina, Costa Rica and Peru, 1980–2005. Paper presented at the ISA 2012 Forum, Argentina: Buenos Aires.

Noy, S. (2013). Globalization, international financial institutions and health policy reform in Latin America. Indiana University.

Noy, S., & Voorend, K. (2016). Social rights and migrant realities: Migration policy reform and migrants’ access to health care in Costa Rica, Argentina, and Chile. Journal of International Migration and Integration, Vol.17(2), 605–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0416-2

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development - OECD. (2017). OECD reviews on health systems: Costa Rica. Evaluation and recommendations

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development - OECD. (2020). Economic studies of the OECD. July, 2020. Retrieved from: Estudios Económicos de la OCDE: Costa Rica. https://www.oecd.org/economy/surveys/costa-rica-2020-OECD-economic-survey-overview-spanish.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Organización Panamericana de la Salud - OPS. (2019). Perfil del sistema y servicios de salud de Costa Rica con base al marco de monitoreo de la Estrategia Regional de Salud Universal. Organización Panamericana de la Salud.

Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS) & Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) (2013). Cinco Estudios acerca del seguro social de salud de Costa Rica. Resúmenes Ejecutivos. San José: OPS/OMS.

Oreggioni, I. (2015). III. El camino hacia la cobertura universal en Uruguay. https://www.paho.org/uru/dmdocuments/Capitulo_3.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Pacheco, J. F., Elizondo, H., & Pacheco, J. C. (2020). El sistema de pensiones en Costa Rica: Institucionalidad, gasto público y sostenibilidad financiera. CEPAL. Serie Macroeconomía del Desarrolo., 87.

Panamerican Health Organization - PAHO. (2015). Perfil del Sistema de Salud—Uruguay 2015. https://www.paho.org/uru/dmdocuments/libro%20PERFIL%20DEL%20SISTEMA%20DE%20SALUD.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Parella, S., & Speroni, T. (2018). Las perspectivas transnacionales para el análisis de la protección social en contextos migratorios. Autoctonía. Revista de Ciencias Sociales e Historia, 2(1), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.23854/autoc.v2i1.59

Pribble, J. (2011). Worlds apart: Social policy regimes in Latin America. Studies in Comparative International Development, 46(2), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-010-9076-6

Prieto, V., Robaina, S., & Koolhaas, M. (2016). Acceso y calidad del empleo de la inmigración reciente en Uruguay. REMHU : Revista Interdisciplinar Da Mobilidade Humana, 24(48), 121–144. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-85852503880004809

Psetizki, V. (2010). Uruguay, un país para migrar. BBC News Mundo. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/america_latina/2010/09/100901_uruguay_inmigrantes_llegada_peaAccessed 14 June 2022

Quesada-Yamasaki, D. (2020). Sostenibilidad del Seguro de Salud en Costa Rica: Un Análisis Multi-dimensional de su Definición. Revista Salud y Administración, 7(20), 29–45.

Rangel, M. (2020). Protección social y migración: El desafío de la inclusión sin racismo ni xenofobia. Serie Políticas Sociales CEPAL, 232, 54. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/45244/1/S1901183_es.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Rivero, P. A. (2019). Si, Pero no Aqui: Percepciones de xenofobia y discriminación hacia migrantes de Venezuela en Colombia, Ecuador y Perú. Oxfam, 21.

Rodríguez, A. (2013). El derecho a la salud en las inmigrantes nicaragüenses: Una realidad a medias desde el trato de igualdad al otro. Emfermería En Costa Rica, 34 (1). https://www.kerwa.ucr.ac.cr/handle/10669/28861. Accessed 14 June 2022

Rojas, K. (2020, February 17th). Voz experta: ¿Cuanto se gasta en salud en Costa Rica? Voz Experta UCR. https://www.ucr.ac.cr/noticias/2020/02/17/vox-experta-cuanto-se-gasta-en-salud-en-costa-rica.html. Accessed 14 June 2022

Salazar, S., & Voorend, K. (2019). Protección social transnacional en Centroamérica. Reflexiones a partir de tres contextos de movilidad. Cahiers Des Amériques Latines, 91, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.4000/cal.9369

Sánchez-Ancochea, D., & Martínez-Franzzoni, J. (2013). Good jobs and social services: How Costa Rica achieved the elusive double incorporation. Palgrave Macmillan.

Senado y la Cámara de Representantes de Uruguay (2007). Ley de Migración., no. 18.250.https://www.oas.org/dil/esp/Ley_Migraciones_Uruguay.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Simandan, D. (2018). Rethinking the health consequences of social class and social mobility | Elsevier Enhanced Reader. Social Science & Medicine, 258–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.037

Sollazzo, A., & Berterretche, R. (2011). El Sistema Nacional Integrado de Salud en Uruguay y los desafíos para la Atención Primaria. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 16, 2829–2840. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232011000600021

Ubasart-González, G., & Minteguiaga, A. (2017). Esping-Andersen en América Latina: El estudio de los regímenes de bienestar. Política y gobierno, XXIV(1), 213–236.

Unger, J.-P., De Paepe, P., Buitrón, R., & Soors, W. (2008). Costa Rica: Achievements of a heterodox health policy. American Journal of Public Health, 98(4), 636–643. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.099598

United Nations. (2020). International migrant stock | population division. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock. Accessed 14 Sept 2021

van Hooren, F. J. (2011). Caring migrants in European welfare regimes: The policies and practice of migrant labour filling the gaps in social care. 250. http://hdl.handle.net/1814/17735. Accessed 14 June 2022

Villalobos Torres, G. P. (2018). El tránsito de migrantes por Costa Rica: El caso de las personas cubanas que persiguen el «sueño americano». Revista Espiga, 16(34), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.22458/re.v17i34.1800

Voorend, K. (2014). “Shifting in” state sovereignty: Social policy and migration control in Costa Rica. Transnational social review: A social work journal. Vol. 4, Núm. 2–3. Pp. 207–225. https://repositorio.iis.ucr.ac.cr/handle/123456789/273

Voorend, K. (2019). ¿Un imán de bienestar en el sur? Migración y política social en Costa Rica. San José: Editorial UCR.

Voorend, K., & Alvarado, D. (2021a). Costa Rica‘s social policy response to COVID-19: Strengthening universalism during the pandemic? (No. 6; CRC 1342 Covid-19 Social Policy Response Series). German Research Foundation. https://www.socialpolicydynamics.de/f/62eb122c1b.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Voorend, K., & Alvarado, D. (2021b). Cruzando fronteras en vulnerabilidad. Estudio de la protección social transnacional en el Sur Global. Revista Rupturas, 41–65. https://doi.org/10.22458/rr.v11i1.3392

Voorend, K., Alvarado, D., & Oviedo, L. Á. (2021). Future demand for migrant labor in Costa Rica. Knomad/World Bank. https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2021-12/KNOMAD%20Working%20Paper%2040-Future%20Demand%20for%20Migrant%20Labor%20in%20Costa%20Rica-Dec%2021.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2022

Voorend, K., Guilarte, J. J., Alvarado, D., & Soto, T. (2021b). Costa Rica country report. DARA Refugee Response Index (RRI) Project. DARA Refugee Response Index (RRI) Project.