Abstract

This paper will explore a model of best practice, the Leverkusen Model, as well as its impact on both the city and the refugees it serves by utilising key stakeholder interviews, civil servants, non-profits, and Syrian refugees living in Leverkusen. The core argument to be presented here is that the dynamic fluidity of the Leverkusen Model, where three bodies (government, Caritas, and the Refugee Council) collaborate to manage the governance responsibilities, allows for more expedited refugee integration into society. This paper utilises an analytical model of multi-level governance to demonstrate its functional processes and show why it can be considered a model of best practice. Started in 2002, the Leverkusen Model of refugee housing has not only saved the city thousands of euros per year in costs associated with refugee housing, but has aided in the cultivation of a very direct, fluid connection between government, civil society, and the refugees themselves. Leverkusen employs a different and novel governance structure of housing for refugees: with direct consultations with Caritas, the largest non-profit in Germany, as well as others, refugees who arrive in Leverkusen are allowed to search for private, decentralised housing from the moment they arrive, regardless of protection status granted by the German government. This paper fills a gap in the existing literature by addressing the adaptation of multi-level governance and collaborative governance in local refugee housing and integration management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction and Background

Nestled in an enclave between Cologne, Düsseldorf, and Wuppertal is Leverkusen, a mid-sized city best known as being the headquarters for multinational pharmaceutical giant Bayer, as well as home to Bundesliga football club Bayer Leverkusen. Its layout engenders the feeling of bordering larger cities, with its mixture of suburban, urban, and bucolic pastures spun together within a border wrapped by a frenetic bus system and punctuated by a few stops on the S-Bahn. Traditionally a ‘worker’s city’ with a history of hosting an older population of Turkish and Greek GastarbeiterFootnote 1, it has remained generally centre-left in its politics (David NelsonFootnote 2 interview 2019).

It is also home to an eponymous model of refugee housing and integration policy. Founded in 2002 in the wake of the refugees fleeing the various conflicts in the former Yugoslavia that followed the collapse of the post-Soviet order in the 1990s, members of the NGOs Caritas and the Refugee Council of Leverkusen convinced the city government that ensuring better quality accommodation and giving refugees access to the private apartment/housing market will both save the city money and ensure greater integration outcomes for the refugees. The Leverkusen Model was born and entrenched into the city’s governance structure, establishing collaborative governance over policy that remains in effect to this day.

The Model’s tenets have also expanded into other areas of integration policy and are a cornerstone of how the city conducts its housing and integration practices, and these tenets have become emboldened by the surge in asylum applications to Germany since 2014. But to what extent does the Leverkusen Model still function as a best practice policy (see Deutscher Bundestag, 2014) among the wide swath of housing integration policies? This paper explores the Leverkusen Model, what supports it, and how it has remained a staple of Leverkusen’s refugee integration policy for nearly two decades when so much of Germany had to adapt on the fly to the influx of refugees in 2014/2015. We will explore this by framing this paper through the following two questions:

-

1.

What dimensions of multi-level governance contribute to the function of the Leverkusen Model?

-

2.

Does the multi-level governance structure of the housing policy affect refugee integration prospects?

In this paper, we will argue, first, that because Leverkusen structured its multi-level governance (MLG) with collaborative ties between the city government and the NGOs Caritas and the Refugee Council, the Model has evolved to encompass tangential areas to housing, such as neighbourhood integration policies. This has strengthened volunteer and local initiatives and approaches to refugee integration and expanded the initial scope of the Model to include civil society as the bedrock of the Model’s governance. Second, the Leverkusen Model’s governance structure is able to move refugees quickly from a state of uncertainty to relative stability and have consistent support for refugees in common markers of integration, i.e. housing, language, education, and work, because of a reasonably centralised civil society apparatus for coordinated volunteer efforts. For this argument, we will define what we mean by best practice and why something can be considered best practice through Marsh and McConnell’s (2010) heuristic for assessing policy success, and Homsy et al. (2019) framework for assessing MLG.

To analyse Leverkusen’s governance practice, we will utilise MLG as a framework on which to both map out and understand the various interconnecting factors that contribute to the Model’s functions. We use MLG as an analytical framework because of its capacity to describe and reveal how interactions in various levels of government and governance partnerships formulate and implement policy (see Stephenson, 2013; Hooghe & Marks, 2003) which then allows us to explain how these interactions function, rather than using another framework that would assume policy implementation is a ‘straight silo’ of decision-making within government (see George, 2004). We also utilise theories of migrant integration to inform us how the governance structure of the Leverkusen Model either facilitates or hinders refugee integration; these theories all contain relevant aspects of how integration, as a concept, functions from both the perception of the refugee and the respective government (see Bourhis et al., 1997), and helps us to better understand how the posture a government takes with regard to refugee integration policy can create either a positive or a hostile environment.

We will first give an overview of MLG and include a discussion of success/failure and best practice. Then, we will review relevant theories of integration. We will then briefly review our methodology before engaging in our analysis of the Leverkusen Model, where we will find that the Model’s collaborative governance, facilitated through dynamic communications between relevant stakeholders, enables the Model’s durability and extension, and makes it an example of best practice within refugee housing and integration policy.

Multi-level Governance as an Organising Framework

MLG, as a method of analysis of governance systems, was developed by Hooghe and Marks (2003) to apply a framework to the increasingly complex interplay in decision and policymaking between the then-newly formed European Union and its member states (see Hooghe et al., 1996). Since its advent, MLG has developed into multiple streams of governance models rather than as a unicellular entity for understanding EU policymaking. Hooghe and Marks (2003) delineate two types, type I and type II. Type I is closely linked to federalism, as the layers of government are nested but have specifically defined jurisdictions where functions within certain policy areas are bundled together to focus on a specific area.

Type II governance is composed of ‘multiple, independent jurisdictions fulfil(ing) distinct functions’ (Ibid: 237), which are made to be task-specific rather than bundled policy areas. There’s no actual limit to the number of jurisdictions so long as each one fulfils a specific function, and they may come and go as issues arise. Type II governance also doesn’t keep strict borders within cities on the jurisdictions of its entities for its constituents.

Type II has seen a relative increase in use recently as different methods of policy instrument implementation have developed; much of this has come from formal government deregulation and privatisation, i.e. utilising specialist organisations in service delivery of policy implementation rather than delivering the service directly from the government (Le Galès, 2011). This has precipitated a change from government to ‘governance’, which has allowed grassroots organisations to take over delivery of smaller aspects of policy delivery (Cairney, 2012: 158).

Inherent in MLG, and especially within type II, is collaborative governance. It entails close ties between governments and third-sector organisations (and the public, either through civic engagement, volunteering, or the like) (Bingham, 2011). Where governments in tandem with specialist organisations can actively and beneficially collaborate and cultivate a society-centred perspective of policy issues, in the ideal case, responses to policy problems are better handled by the governance structure (Sellers, 2011).

Much of this can be traced to the development of subject area networks at the local level, which often advocate for transparent deliberation and close ties with government for service delivery (Kjær, 2004). In this way, as Cairney (2012) describes, there are two essential characteristics that arise: first, that there is interdependence between public and private organisations, and second, that governments have the authority but not the capacity to follow through on policies on their own (Cairney, 2012: 157). Without the private actors who have become the delivery specialists, then there is no policy implementation.

Homsy et al. (2019) developed a framework for understanding MLG in their study of sustainability governance, based on previous analyses of MLG systems in different settings. The framework is composed of five parts: first, the coordinating and sanctioning role of a central authority; second, engagement with civil society; third, co-production of knowledge; fourth, capacity provision; and fifth, framing of co-benefits. Their framework is nested in the locality of multi-level governance and the necessity of policy issues, in their case environmental governance, to utilise and operationalise distinctly local expertise.

Best Practice and Success

The framework dovetails into a discussion of what makes a successful policy implementation within the realm of MLG, and subsequently a model of best practice. Unfortunately, if determining that a policy was either a success or a failure were a straightforward, quantifiable process, academia around the subject wouldn’t be so prone to argument about what can truly constitute either concept (see McConnell, 2015). Both success and failure of policies and their objectives, unsurprisingly, exist in a spectrum of implementation and contextual analysis, as well as through perceptions of how policies change over time.

‘Best practice’ is, similarly, subjective: deciding what the benchmark is, as well as factors surrounding historical contexts, can turn something that was ‘best practice’ into ‘bad practice’ (Löffler, 2000). For us, the discussion of best practice will revolve around duration, maintenance, and expansion of good policy, as well as its spread to other cities or regions, through the discussion of policy success.

As with any public policy, considerations have to be made as to the context in which it is developed, whether it has defined goals, what the targeted population is, what the unintended consequences were of the policy’s implementation, who were the main and secondary stakeholders, was there a power disparity in the relevant stakeholders, et al. before beginning an assessment of a policy’s success or failure (McConnell, 2015). Marsh and McConnell (2010: 571) highlight a heuristic guideline about how to assess policy success across three dimensions: the process (the development of the policy, i.e. the policymaking stages), the programmatic (the operations, the implementation, and the outcome), and the political (popular or not for the government). The heuristic asks questions about the possible indicators of success and the places where to look for evidence, i.e. in how the policy was implemented, who benefited, and whether it was popular.

In the case of refugee housing policy, what we search for in terms of benchmarks for policy success or failure is, similarly, piecemeal. We will refer back to Marsh and McConnell’s (2010: 580) list of considerations when asking if the Leverkusen Model is successful or not, or somewhere in between: is the policy durable? Does it change/get amended often to contravene or winnow its original intentions, or does it expand? Whose interests are primarily being served by the policy? Are those interests one-sided, i.e. in the interest of cost-savings on behalf of government budgets, or is there a dual interest for the public? Is it popular among the citizenry? Can this policy be viewed in isolation as a success/failure, or was there an exogenous factor that altered the policy’s trajectory? These notions of temporality, maintenance, power relationships, popularity, connection to other related policies, and internal/external impacts/conflicts will carry over into our analyses.

The next section will give an overview of the various theories around migrant integration, touching on how governments can choose to orient themselves with regard to societal access for refugees.

Theories of Integration as a Roadmap

Theories surrounding how migrants integrate are typically divided between what migrants do, what states/governments do, and what society does. For migrants, Berry’s (2005) acculturation model analyses how individuals may position themselves with regard to their integration outlooks, where they can choose to wholly assimilate into a new culture and ‘disregard’ their home country; become segregated into only interacting with those from their own culture; integrate into the norms of society and position themselves on the ‘border’ between their home culture and the new one; or become marginalised and choose to interact with neither those from their home country or the new society (Berry, 2005: 705).

Important in this facet of integration is not just the individual migrant’s needs, but how the new society around the migrant positions itself with regard to inclusivity or otherwise (Murphy, 1977). In situations where the receiving society have histories of intaking migrants from a culture similar to one that is newly arriving, acculturation aspects may be facilitated, though this is not always guaranteed (Lebedva & Tatarko, 2004). Because receiving societies may not be uniformly in favour of a new group of migrants due to extemporaneous societal issues, it then rests on the government to encourage interaction between societal actors and the new migrants (Koos & Seibel, 2019).

For refugees, however, this integration aspect is marred by possible instances of post-traumatic stress from fleeing their home countries (Allen et al., 2006). Some may not be able to adjust or integrate as quickly as a government would like them to due to this past trauma, especially as demands placed on refugees may be more than those placed on general migrants (Söhn, 2013). Refugees then must walk a fine line between perceiving their home countries as places of trauma, and of worrying about possible friends/family they had to leave behind in order to survive (Al-Ali, 2001). They may live physically in one place but psychologically remain ‘back home’, making a government’s integration demands on a refugee more difficult (Erdal & Oeppen, 2013).

Because of this, refugees may take up more ‘transnational’ lives in their new country, balancing themselves between forming new lives and maintaining strong cultural ties with their homelands (Vertovec, 2009). Contrary to what one may believe, transnational aspects of living in a new country may aid in integration into that country (Sert, 2012). Transnationalism needn’t be maintaining active communications with those in a homeland, or sending money to family still at home; it can be something as simple as finding foods native to one’s home in the new country, or living near a diaspora that is also more familiar with the new country than the refugee may be (Ehrkamp, 2005).

How a government positions itself with regard to integration policies can strongly determine integration outcomes for all (Bendel et al., 2019; Bourhis et al., 1997; Nuissl et al., 2019). Countries that place strong restrictions on refugees and migrants at large, or implement ‘colour-blind’ policies, risk alienating those who aren’t accustomed to how societal mechanics and services operate (Allport, 1954; Phillimore, 2011). Many states now engage in civic integration, which places demands on refugees and general migrants to adhere to the standards provided by the state in order to have a good staying probability (Joppke, 2007). The core belief surrounding civic integration is that states promote those values they believe should be held by its citizens (Goodman, 2010). However, as found by Goodman and Wright (2015), those states whose policies scored higher on the CIVIX civic integration scale didn’t have an immediate effect of integrating immigrants into society,Footnote 3 confirming Ersbøll and Gravesen’s (2010) study, which found that it was ‘friends, family, and work’ that aided migrant integration rather than requirements laid down by the state (Ersbøll & Gravesen, 2010: 41).

This leads into the theory of interculturalism, a nascent school of thought in migrant integration that posits that direct, positive, and continuous contact between different social groups promotes integration between those groups (Zapata Barrero, 2015). Interculturalism is differentiated from multiculturalism in its belief that there must be interactions between different groups in order to promote a more cohesive culture, rather than the general living side-by-side nature of multiculturalism (Meer & Modood, 2012). In the case of Germany, this practice of encouraging interaction between refugees and the native population was done mostly within the scope of the massive civil society outpouring in 2015 through various initiatives, much of which was independent from both national and local government (Aumüller et al., 2015; Doomernik & Ardon, 2018; Dukic et al., 2017). The idea has also culminated in programs such as Startblok in the Netherlands, which both sought to tackle its housing shortage and the necessity to introduce refugees into society by constructing housing units where young Dutch can live side-by-side with new refugees (Czischke & Huisman, 2018).

When trying to model a structure of how integration happens, Startblok adheres to the basic design of Ager and Strang’s (2008) integration framework, which posits that material means (work, housing, etc.) can lead to social bridges (those connections made with members of the new society), which are the strong connecting tissue that leads into deeper understanding of the new culture. However, Ager and Strang’s framework runs into the problem that different cities and countries focus on different aspects of integration, typically within trying to get refugees to participate in and contribute to the economy as quickly as possible rather than working on all aspects of integration simultaneously, harking back to civic integration (Maroufi, 2017).

As the saying goes, one cannot put the cart before the horse. Excessive pressure from government to fulfil one need of the state without determining the needs of the refugees leads to what Ersbøll and Gravesen (2010) found, while relying solely on volunteer initiatives for integration services without government action or aid can lead to extreme uncertainty for refugees (Phillimore, 2012). There must be a balance between the residency demands of the government and the needs of refugees to ease themselves into a new society, and in the following sections, we will analyse just how it is that the Leverkusen Model achieves that balance.

The next section briefly discusses the methodology before detailing the structure of the Leverkusen Model and how it functions practically for refugees.

Methodology

Field work conducted in Leverkusen included 18 semi-structured interviews with Syrian refugees, volunteers who have worked or still work with refugees, either personally or in the mass accommodations, NGO workers, and members of the civil service. The ages of the Syrian interview participants ranged from 25 to 55 and were composed of 1 woman and 6 men. Syrians were the only nationality interviewed because of the 2016 Integration Law’s (Integrationsgesetz) stipulation that asylum seekers from countries with a good staying prospectFootnote 4 can access integration benefits before a formal asylum decision has been granted. It has largely benefited asylum seekers from Syria, who are approved in more than 93% of cases (BAMF, 2018).

Only those (non-refugee) interviewees who have given permission to be identified will be; otherwise, respondents are given a randomly assigned set of letters for identification. Interviews were conducted in German and English and lasted, on average, for an hour. Interviewees were contacted through e-mail/phone initially, and then further interview subjects were obtained via chain referrals or ‘snowballing’.

Semi-structured interviews were utilised because of the necessity to understand the subjective nature of both one’s integration into Germany and how one came to access the benefits of integration, i.e. languages and finding help from volunteers, and capture the contextual essence of their social settings (Devine, 2002: 199). They also enable interview participants to not be confined to more rigid lines of questioning, which can exclude information that may be useful for the study but not raised within hard-coded interview questions. Additionally, interviews allow for inductive analysis and better understanding of the complex interdependences that arise from integration and multi-level governance structures (Vromen, 2010: 257).

Interview questions for governance partners (civil servants and Caritas/Refugee Council employees) were mainly focussed on issues surrounding communication between governance partners (both formal and informal, i.e. regular meetings and contact regarding individual refugee cases), interaction between government/NGO employees and refugees, policy input from other groups,Footnote 5 practices and issues of policy implementation, and pragmatic experiences surrounding the Model’s primary focus, i.e. obtaining private housing for refugees.

Interview questions for refugee participants were focussed on their interactions with the structure of the Model’s policy governance, including the governance-centralised volunteer efforts and neighbourhood policies. This included experiences searching for housing, interactions with governance officials (if any occurred), sentiments surrounding their places of residence (both within the mass accommodations and private residences), and experiences working on behalf of the Model’s policy governance, if they did.

These two areas of focus to guide the semi-structured interviews provided a more complete view as to how the Model’s policy governance functioned at both the starting point (governance mechanics) and the ending point (individual refugees obtaining housing).

There are possible sources of bias in the selection of Syrian refugee subjects. All but one of the Syrians interviewed were either previously proficient in English or still maintained some level of English-speaking ability. This would indicate that the interview participants came from an educated background and that human capital may allow for them to better adapt to German society than would someone who came from a lower-educated background. Additionally, chain referrals run the risk of the initial interview partner only referring those living in ‘best case scenarios’ rather than those who may be living in worse circumstances.

Additionally, document analysis (of those provided by interview participants) was conducted. Documents obtained throughout the course of the empirical research supplemented the data provided by interview participants.

Finally, with a view to the previous information, we undertook policy analysis through assessments provided by those working within the governance framework (civil servants, Caritas and Refugee Council employees) and refugees. This was bolstered by policy documents from the city of Leverkusen, which has released regular updates to both its integration policy concept and its housing initiatives. These coalesce into the structural foundations in the next section and allow us to better understand how and why the Model expanded as it has.

The Leverkusen Model: Findings

From 2002: Governance

Leverkusen was an unlikely city to develop what might be termed a ‘best practice’ model of governance on refugee housing and integration (as referred to in Deutscher Bundestag, 2014). In 2002, the city government was reticent to allow refugees to enter the private housing market (Schillings & Märtens, 2015). Many in the city government believed that refugees would have a hard time using basic utilities and would possibly burn down their new residences (Refugee Council employee interview 2019).

However, the city government allowed a pilot program where employees from Caritas and the Refugee Council would actively search for flats on behalf of refugees (Caritas employee ‘A’ interview, 2019). Once the pilot program was completed and Caritas and the Refugee Council had moved the 80 selected refugees out of the mass accommodations and into private apartments, the city found it saved €76,000; the Model was then implemented full-time into the city’s integration framework (Schillings & Märtens, 2015). From then, all but one of the 12 refugee accommodations in Leverkusen were able to close due to the Model’s implementation. These were reopened in 2014 to cope with rising asylum cases (Stadt Leverkusen, Dezernat für Bürger, Umwelt und Soziale, 2017).

The Model sets down 3 standard rules: first, that there is no minimum mandatory time spent in mass accommodation,Footnote 6 unlike in cities such as neighbouring Cologne (Adam et al., 2019); refugees, regardless of status, are able to search for and obtain a private room in a house/apartment upon arriving in the city. Second, non-profit Caritas maintains a constant presence in every refugee accommodation and actively helps refugees find places to live. Third, that there would be active communication and coordination between Caritas, the Refugee Council, the Integration Council, and the city government (Caritas internal document obtained, 2019).

The Model is supported through the interconnected, collaborative governance (type II) structure established between the Leverkusen government and the city’s main NGOs, as well as the secondary NGOs that are kept within the circle of policy planning. Two key tenets to the functioning of this collaborative governance structure are direct and active communications between the NGOs and the city government, and involvement of civil society/citizenry, reflecting the technocratic characteristics of the governance structure (Scholten, 2013: 220). Besides Caritas social workers working alongside city government social workers in refugee accommodations, civil service employees have direct and constant communications with the various NGOs:

[W]e have a very good structure of co-working with different institutions like AWO, Caritas, Flüchtlingsrat, and Kommmunales Integrationszentrum… I think I have like, four or five meetings every week with different actors, the communication is quite intense. (David Nelson interview 2019).

The city developed a structured ‘communications flowchart’ between the ‘controlling group’ (i.e. the government institutions typically responsible for policy areas, such as the Department of Education or the Social Services Department) and the ‘specialist groups in integration’, which can be both other government entities and specialist NGOs and organisations dedicated to those policy areas, i.e. the Department of Education has direct input from the Social Services Department and the head of the Migration Office (Stadt Leverkusen Kommunales Integrationszentrum, 2019: 8–9).

Volunteer services are also coordinated between the city government and the NGOs. As ZOL, a city government volunteer coordinator stated:

We coordinate with all the supporters and institutions that work with refugees, and they ask me much because they also mostly organise the appointments for the refugees. For example, doctor appointments, or other conversations they’re asking me if they have something then and then write me. It’s very constant contact… we have work groups and other meetings that we do with full-time [professional] workers from Caritas, Refugee Council, Fachbereich Soziales, community integration centre, and everything possible that also does integration work, and we meet together regularly. I am, for example, in a work group with the [previous groups mentioned] from the city of Leverkusen Community Integration Centre and we meet and plan some events together. (ZOL Interview 2019).

Present Day

There are 12 extant refugee accommodations in Leverkusen dating back to 2002, though several will be consolidated into one newly built structure at Sandstraße to accommodate 450 (out of a total of 1105 spaces). By 2017, Leverkusen had a total refugee population of 3684Footnote 7 (Stadt Leverkusen, Dezernat für Bürger & Umwelt und Soziale, 2017). Much like other cities in Germany during the height of the asylum movement in 2014–2015, large spaces such as school gyms and old military barracks had to be sequestered as temporary shelters. The city updated its integration conceptualisation to reflect on and expand the collaborative structure in the face of a new wave of refugees declaring asylum in Germany, and heavily utilised centralised and coordinated volunteer efforts to facilitate private housing efforts for refugees (Ibid).

The new concept reinforced the city’s position that integration is a collective action that necessitates a ‘constructive interplay of educational institutions, charities, business enterprises and other civil society groups… [and] the resources, actions, and motivations of migrants also play a decisive role’, with housing and accommodation existing as one of the key factors in facilitating integration (Stadt Leverkusen Kommunales Integrationszentrum, 2017: 8). Consistent collaboration and coordination between the governance partners enable increased interactions between refugees and the locals through directed volunteer efforts.

[B]ecause of organising even meeting points by volunteers inside the camps or beside in the neighbourhood by the camps and there are certain contacts even to German people… by this chain houses are found even the expectation of refugees of certain people or of certain people who I meet increase. (Refugee council employee interview 2019)

Furthermore, the new integration concept proposed the extension of ‘intercultural offerings’ and facilitating the creation of new representative groups for refugees in order to ensure a two-way understanding of integration, i.e. that refugee voices and needs can be adequately and directly communicated to the government by refugees themselves rather than through interlocutors, who may misunderstand more specific cultural issues (Stadt Leverkusen Kommunales Integrationszentrum, 2017: 14–15; see Zapata Barrero, 2015).

Leverkusen also initiated cultural sensitivity seminars for its employees, reflecting further investment into an intercultural operating viewpoint (Stadt Leverkusen Kommunales Integrationszentrum, 2019: 11). Inviting migrant-oriented perspectives into those who both implement and craft policy is a key tenet of removing the one-sided nature of integration policies that can often lead to uncertainty for refugees (see Ersbøll & Gravesen, 2010).

Part of this intercultural work has been carried out through the Leverkusen Integrationsrat (Integration Council), an arm of the Leverkusen government that specifically works to facilitate the creation and support the maintenance of migrant organisations in Leverkusen, an important facet in transnationalistic integration (see Sert, 2012). Contact first begins as a relay from the city’s NGOs directly to the Integrationsrat.

When a new group, for example, the Syrian Kurds, when they organise, then comes Caritas or the Flüchtlingsrat, they tell me there is a new group, and here in the house we have rooms that they can use for their groups. Because that is often, the first question, where can we meet? (Andreas LaukötterFootnote 8 interview 2019).

The refugee-representative organisations working through the Integrationsrat act almost as a ‘council’ of representatives on behalf of refugees and interact with the government to represent their interests (Ibid), enabling further strengthening of the city’s governance structure through inclusion of refugee-representative groups (see Haque, 2011). The city recently facilitated the creation of a representative Kurdish cultural group, of which one refugee interview participant (KPL) is a supporting member. The city also pledged to increase the ‘intercultural orientation’ of its employee base, which would ensure diverse employees with various cultural and linguistic backgrounds (Stadt Leverkusen Kommunales Integrationszentrum, 2017: 14).

By establishing a more diverse civil service, the city government can then be more responsive and dynamic in its approaches to integration, such as through its volunteer coordination efforts (Leverkusen refugee accommodation civil servant interview 2019a), and sensitive to cultural peculiarities that would not otherwise be known by a more homogeneous employee corpus. For instance, AQL, a Syrian refugee who had a corporate job in Syria, chose to work as a social officer for refugees near Bonn while living in Leverkusen (AQL interview 2019).

Through this deepening and widening of the governance practices surrounding the Model, as well as the centralisation of volunteer efforts, the temporary spaces, such as school gyms, were closed ahead of the city’s initial proposed timetable (Leverkusener Anzeiger, 2017).

How Leverkusen Works for Refugees

The lack of restrictions on refugees’ ability to find spaces in which to live in Leverkusen is facilitated through the cooperation and collaboration between the city’s government, the civil society organisations, and the volunteers; all of which helps a refugee begin to acclimate to the city on the first day of their arrival.

I was signing up to search for an apartment, and that’s good in Leverkusen that one could find an apartment search even though one doesn’t have an aufenthaltstitel [staying permit]. That was a big help to find, not every city is like that. One can do that in Leverkusen. (KPL interview 2019)

The removal of restrictions of integration benefit access was expanded to the city’s offered formal language courses (Stadt Leverkusen Kommunales Integrationszentrum, 2019: 12–13; see Marsh & McConnell, 2010). Refugees can then register for German classes as soon as they arrive in the city regardless of whether they’ve received an asylum decision from the BAMF (see Ager & Strang, 2008).

However, while the German courses help with language acquisition, all interview participants agreed that it was the volunteers that helped the refugees acquire German faster, as well as find private accommodations. One of the most reliable means of centralising volunteer help for refugees within Leverkusen has been through the sprachcafes. Each major (and many smaller) NGO in Leverkusen hosts a sprachcafe that is open for refugees and Germans alike. Typically, the NGO offices are near the accommodations, allowing for intercultural exchanges (see Zapata Barrero, 2015) between natives and the refugees.

He helped me to find an apartment, he helped me to learn the language, he helped me with the government documents because I couldn’t speak well… (BDL interview 2019)

I was [in the accommodation] for 6 months, but I didn’t stay there much. I was always out, for example, we went to cafes, to learn German, to see how quickly we can learn German. Therefore I had only six months of staying there… We didn’t learn any German in Sandstraße [accommodation] sprachkurs. We had there… a sprachkurs, and that was also voluntarily… next door was an international café. The people meet there and talk, for example, they help when one gets mail and we don’t understand. And I show them, and they helped me… more helpful, the international café [was than the sprachkurs]. They help a lot when you need, for example, for post, they take time, they clear things up well so you can understand. (YSL interview 2019)

Refugees who received help from the volunteers also became volunteers themselves and helped the NGOs and city government whenever they could offer it. Besides KPL and YSL, MOL, AQL, BQL, BDL, and AWL all volunteered through either the city government or the NGOs to help newly arrived refugees with some of the anxieties and difficulties that they faced when they first arrived. This self-reinforcing mechanism enables a sense of familiarity and can ease the transition into Leverkusen (see Vertovec, 2009), and is enabled by the interconnections made by the city’s governance structure.

For new arrivals, I had helped in these cafes when they put forward questions, I had accompanied them when they needed German volunteers, and I was always translating and a [Syrian] wanted to find a flat for himself, there was volunteers… They had asked me where do you live, I said in the Sandstraße, and ‘you have no place to live, and you help the people to search for apartments?’ I said it’s normal, I like to help. (KPL interview 2019)

I have a contract with the city as a volunteer. Sometimes they call me, they say a family needs a translator or a companion to a hospital or a school or to Auslanderbehorde and so on, and if I have time I confirm. (AQL interview 2019)

I've been working with Syrian refugees in camps generally for the first two years. (MOL interview 2019)

Voluntary service for refugee who want to make culture and language mittler, so I do this job and the refugees who want to make some voluntary service for one year, with the Bundesfreiwilligendienst. So I worked there for 2 years and 8 months more. I still work there, and I am a seminar leader, group leader who make seminar with other people as a job also. (AWL interview 2019)

Because Germany’s housing market is largely informal and housing is attained more through networks and contacts rather than formal searches through advertisements, the Model’s encouragement of contact between citizens and refugees achieves two facets of most of the aforementioned theories around integration, i.e. establishing relationships with the native culture and a sense of agency (see Vey, 2018; Murdie, 2008) or control over their lives in the new country by allowing them to secure a residence.

And the aspect, which is very important, as well, that there haven't been any bigger conflicts following the lodging in private rooms. There have been many social impact, of course for the people themselves. To visit the language courses, to communicate with their neighbourhoods, to have contact with the other children, to school and kindergarten around their home. (Caritas employee ‘A’ interview 2019)

In 2017, the city found that, in 2015, 450 refugees were able to move from the accommodations into private spaces, while in 2016, 411 refugees were able to obtain private spaces from a total refugee population of ~ 3500 in both years; unfortunately, the report doesn’t delineate what percentage of those ~ 3500 lived in accommodations or otherwise, though at the time there were 1105 beds within refugee accommodations (Stadt Leverkusen, Dezernat für Bürger & Umwelt und Soziale, 2017). A Leverkusen civil servant interviewed for this study reported that, in 2017 (amid falling asylum seeker numbers), 267 people moved out of the accommodations; in 2018, 411; in 2019, 308; and in the first 8 months of 2020, 137 (Leverkusen refugee accommodation civil servant interview 2019; figures updated.).

This indicates that there is a consistent turnover of spaces with refugees entering the private housing market, facilitated through the interaction between the volunteers and the refugees rather than Caritas or the city government, which Caritas states have become the most important factor for refugees to find housing and ultimately adapt to living in Germany (Caritas employee ‘B’ interview 2019).

The city government, partnered with Caritas, started a program in 2019 called Willkommen im Quartier (Welcome to the Neighbourhood) to introduce refugees to native Germans in the neighbourhood in which they’ll live. Native Germans are responsible for acting as tour guides for the refugees’ new neighbourhoods. There have been 11 pilots of this program, which involve guided tours (with language support) of the areas of commerce, culture, and leisure. The Job Centre supports training for the tour guides so as to impart practical information to the refugees, such as on the technical aspects of accessing the health system and getting a mobile phone contract (JOB Service Employment Promotion Leverkusen gGmbH, 2019; Stadt Leverkusen Kommunales Integrationszentrum, 2019: 26).

In situations where city or Caritas employees act in inappropriate ways in the accommodations, refugees have mechanisms to ensure transparency and accountability, another essential part of collaborative governance (see Sellers, 2011). In the case of AWL, a Caritas employee in the accommodation acted in a way to which many residents took offence. AWL petitioned to have the employee removed from the housing, but many refugees were afraid to speak up out of fear for their asylum status. Even when he went to speak with Caritas, he found they weren’t receptive to his claims. He then contacted the mayor’s office. ‘And after that they come from there, they see the situation, they speak with some people there, and they find it not good. They transfer [the Caritas employee] from the camp. (AWL Interview 2019)’.

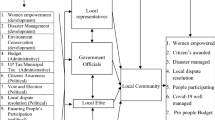

Figure 1 depicts a diagram outlining the Leverkusen Model’s governance structure.

Organising Leverkusen’s MLG Infrastructure

Utilising Homsy et al. (2019) MLG framework, we can better understand and detail the Leverkusen Model’s structure to show how the connections within its governance reinforce the Model’s functioning, as shown in Table 1.

The next section will analyse the Leverkusen Model as an example of best practice utilising Marsh and McConnell’s (2010) heuristic to assess policy success.

Assessing Policy Success and Best Practice

While Leverkusen has been referred to as a model of best practice in discussions surrounding refugee housing and integration policies (see Deutscher Bundestag, 2014), we should assess the Leverkusen Model’s ‘success or failure’ niche in order to establish that it hits all the marks of what we would want to see under a policy that can be called one of best practice.

We refer back to our tenets of determining success or failure, i.e. temporality (i.e. duration), maintenance, power relationships, popularity, connection to other related policies, and internal/external conflicts (Marsh & McConnell, 2010). Table 2 breaks down the relative favourability/unfavourability of Leverkusen under the criteria.

The Leverkusen Model has adapted to more expedited means for searching for and allocating housing due to the availability of the internet, as opposed to when it was first developed in 2002. It has remained popular not only with the party currently in power (SPD), but also with the centre-right CDU; the only party that opposes it is the far-right party, which has very little influence in LeverkusenFootnote 9 (Leverkusen refugee accommodation civil servant interview 2019). Power relationships are managed by consistent collaborative governance and transparency between the governance partners, along with constant communication (David Nelson interview 2019; Leverkusen refugee accommodation civil servant interview 2019; ZOL interview 2019). The city also encourages contact between refugees and citizens through various programs that are also coordinated with the city’s NGOs, and this contact facilitates better understandings for refugees of the various necessities the German government institutes for integration (KPL interview 2019; AQL interview 2019; BQL interview 2019). This constant interaction between the governance partners means that there is little conflict as policy implementations are constantly discussed.

A Reflection on ‘Best Practice’

From here, we can see that the Leverkusen Model can be considered a relative ‘policy success’ in that there hasn’t been an effort to either redefine or reform it; rather, the city has expanded it. But then what makes a policy success a model of best practice? Beyond the reference within policy discussions within the Deutscher Bundestag (2014), we can argue that best practice is a policy that allows a government to both have its cake and eat it, or obtain a strong balance of policy outcomes with few negative outcomes or externalities (see Löffler, 2000). In the case of Leverkusen, this much is evident: the city’s goals were to save on expenditures for refugee accommodations while the NGOs sought to facilitate refugee entry into society through private housing. Both were obtained.

That the policy has endured and expanded over 18 years (and within the most recent asylum surge) is further testament not only to the political popularity of the Model within Leverkusen as a policy staple, but also to its almost common-sense components that allow interactions with refugees at all levels of society, from city government to NGO to average citizen. This has enabled the Leverkusen Model to be adopted or partially implemented by neighbouring cities within North-Rhein Westphalia (Flüchtlingsrat, 2015) and for the Model to be recommended as a party policy within Die Linke (Die Linke, 2013).

The Leverkusen Model can be considered a model of best practice due to the coherence of its type II MLG collaborative structure, where roles are clearly defined between all the relevant actors and there are transparent methods of checks-and-balances between all the actors to ensure that all aspects of the Model run as smoothly as possible. Communication between governance parties is continuous. The entire governance structure then promotes direct contact between citizens and refugees, exemplifying proactive integration through promoted contact (Maroufi, 2017; Zapata Barrero, 2015). It is both a proactive and reactive Model, where the only major problem within it is something the Model itself cannot solve: the general supply of available housing.

Discussion

While we’ve argued that the Leverkusen Model is one of best practice, it is important to reiterate the limitation of this study: the small sample size and narrowed national background of refugee responses can only serve to illustrate how the Leverkusen Model functions on a smaller scale rather than for refugees at large in Leverkusen. However, and reflecting on our first research question, we’ve found that all governance partners are satisfied with how the Model operates within the scope of collaborative governance. From the civil service to the refugee-facing organisations, relevant stakeholders are given input into policy implementation.

Within the scope of the second question, what we’ve found is an interesting by-product of a housing search: because Germany’s housing market is informal and relies on network chains of local knowledge, promoted volunteer contact became the primary method for refugees to find private housing. The MLG structure of the Model allows for volunteer responses to be coordinated between the NGOs and the government (ZOL interview 2019; Refugee Council employee interview 2019), which then promotes intercultural contact and encourages language acquisition (YSL interview 2019; BDL interview 2019). As within Ager and Strang’s (2008) integration model, refugee connections with and to nationals are integral to overall integration.

From this, we can perceive civil society as being the most important foundation for refugee integration through housing in Leverkusen. This implication holds wide-ranging importance for refugee policies writ large: an engaged civil society and volunteer effort, where contact between nationals and refugees is promoted by the government, can better facilitate refugee integration. Whether it’s through obtaining housing or having a friend with whom one can practice the local language, a government policy that enables its citizenry to aid in acclimating refugees to their new surroundings enjoys support from its citizens, its governance partners, and the policy’s recipients, the refugees themselves.

The Model also enables refugees to easily become volunteers themselves through its governance structure, which presents a strong transnationalistic (see Vertovec, 2009) element to promote new refugee integration. This self-reinforcing mechanism allows the Model to move beyond a more standard interculturalist approach (see Zapata Barrero, 2015) by allowing someone familiar with two different cultures to act as a bridge for someone who is completely new to the country.

Given the general structuring of governance across cities in Germany (with type I and type II utilised widely), the Model bears relevance to many cities that either struggled to react well to the initial refugee influx in 2014–2015, or severely restricted the rights of refuges to access societal resources due to perceived financial costs. The Model’s success over nearly two decades demonstrates that it is effective for both government and refugees. While there are expected administrative difficulties and issues in day-to-day delegation, it is a system that has enabled the Leverkusen government to save on expenditures while enabling refugees to become contributing members of society with relative ease.

The only speed bump to the Model’s wider application and implementation is the ongoing housing supply crisis across the plurality of German cities, which falls in tandem with a general affordability crisis. Leverkusen has engaged in a building program to ensure a growing population can be adequately housed across the city. Whether it will be enough to adjust to sudden population influxes from large-scale refugee movements, for example, remains to be seen.

Further longitudinal study into the implementation of the Leverkusen Model is warranted in order to best ascertain its merits, which will not be difficult given the Leverkusen Model will likely continue into the future.

Availability of Data and Material

Data from interviews is encrypted and held securely to protect the identifications of the interview partners.

Code Availability

None.

Notes

The Gastarbeiter were migrants brought into Germany in the 1960s and 1970s to fill vacant jobs who then remained after the Gastarbeiter program ended (Brubaker, 1992).

David Nelson is the city’s Koordinator EinrichtungsbetreuerInnen (Coordinator of facility supervisors).

At the time Goodman (2010) developed the CIVIX index in ~ 2008–2009, Germany still had more restrictive requirements and more difficult/unclear paths and access to citizenship/permanent residence before the passage of the 2016 Integration Law.

Defined as any nationality that has higher than 50% acceptance in Germany (see BAMF, 2018).

This includes non-policy governance groups such as Jürgen Dreyer’s church, which provides neighbourhood support for refugees, and refugee-representative groups, such as those representing specific ethnicities/nationalities (Jürgen Dreyer interview 2019).

The only exception to this rule is those asylum seekers who have a non-zero chance of claiming asylum, such as those classified under Sect. 15a of the Aufenthaltsgesetz, those from other EU states, or those who are found to have passed through a safe third country.

The city’s official publications do not differentiate the population of refugees living in mass accommodations from those living outside of them.

Andreas Laukötter is the Geschäftsführer des Integrationsrates (Managing Director of the Integration Council).

Alternativ für Deutschland (AfD) holds 3 seats out of 52 in the Leverkusen city council (Der Landeswahlleiter des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, 2020).

References

Adam, F., Föbker, S., Imani, D., Pfaffenbach, C., Weiss, G., & Wiegandt, C-C. (2019). Lost in transition? Integration of refugees into the local housing market in Germany. Journal of Urban Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1562302 [Accessed 13 Dec 2019].

Ager, A., Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies [online], 21(2), 166–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016 [Accessed 17 Jan 2018].

Al-Ali, N. (2001). Trans- or a-national? Bosnian refugees in the UK and the Netherlands. In N. Al-Ali & K. Koser (Eds.), New Approaches to Migration? Transnational communities and the transformation of home (pp. 96–117). Routledge.

Allen, J., Vaage, A., & Hauff, E. (2006). Refugees and asylum seekers in societies. In D. Sam & J. Berry (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 198–217). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489891.017 [Accessed 23 Oct 2019].

Allport, G.W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Aumüller, J., Daphi, P., & Biesenkamp, C. (2015). Die Aufnahme von Flüchtlingen in den Bundesländern und Kommunen Behördliche Praxis und zivilgesellschaftliches Engagement, Robert Bosch Stiftung, 2015. [online] Available at: https://www.bosch-stiftung.de/de/publikation/die-aufnahme-von-fluechtlingen-den-bundeslaendern-und-kommunen [Accessed 20 Nov 2017].

Bendel, P., Schammann, H., Heimann, C., & Stürner, J. (2019). A local turn for European refugee politics, Heinrich Böll Foundation, March 2019, Berlin. [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.25530/03552.5 [Accessed 5 Apr 2019].

Berry, J. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013. [Accessed 18 Jan 2018].

Bingham, L. (2011). Collaborative governance. In M. Bevir (Ed.) The SAGE handbook of governance (pp. 386–401). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446200964.n25.

Bourhis, R., Moïse, L., Perreault, S., & Senécal, S. (1997). Towards an interactive acculturation model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology, 32(6), 369–386. [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/002075997400629 [Accessed 13 Jan 2020].

Brubaker, R. (1992). Citizenship and nationhood in France and Germany. Harvard University Press.

Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF). (2018). Entitlement to Asylum, 28 November 2018. Available at: https://www.bamf.de/EN/Themen/AsylFluechtlingsschutz/AblaufAsylverfahrens/Schutzformen/Asylberechtigung/asylberechtigung-node.html [Accessed 9 May 2019].

Cairney, P. (2012). Understanding public policy: Theories and issues. Palgrave Macmillan.

Caritas. (2019). Sozialpaedagogische Begleitung des Unterbringungskonzeptes/Beratung zur Temporaeren Integration. Caritas Internal Document.

Czischke, D., & Huisman, C. (2018). Integration through collaborative housing? Dutch Starters and Refugees Forming Self-Managing Communities in Amsterdam. Urban Planning, 3(4), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v3i4.1727. [Accessed 23 Mar 2019].

Der Landeswahlleiter des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen. (2020). Kommunalwahlen 2020, Endgültiges Ergebnis für die Stadtratswahl: Krfr. Stadt Leverkusen. 13 September 2020. [online]. Available at: https://www.wahlergebnisse.nrw/kommunalwahlen/2020/aktuell/a316000kw2000.shtml [Accessed 26 May 2021].

Deutscher Bundestag. (2014). Entwurf eines Gesetzes über Maßnahmen im Bauplanungsrecht zur Erleichterung der Unterbringung von Flüchtlingen. Ausschuss für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit BT-Drucksache 18/2752. [online]. Available at: https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/362450/ac1d245b825c845d83f25e5cf5f7f440/Protokoll-18-24-data.pdf [Accessed 8 Oct 2018].

Devine, F. (2002). Qualitative Methods, in Marsh, D. & Stoker, S. (2002). Theory and methods in political science: Second Edition. Palgrave Macmillan.

Die Linke. (2013). Konzept einer dezentralen Unterbringung von AsylbewerberInnen und geduldeten MigrantInnen für die Stadt Brühl. Eckhard Riedel, Fraktionsvorsitzender, 20/09/2013. [online]. Available at: https://www.dielinke-bruehl.de/fileadmin/lcmssvbruehl/Dokumente/Dezentrale_Unterbringung_AsylbewerberInnen.pdf [Accessed 29 Oct 2018].

Doomernik, J., & Ardon, D. (2018). The city as an agent of refugee integration. Urban Planning (ISSN: 2183–7635) 2018, 3(4), 91–100. [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v3i4.1646 [Accessed 17 Jul 2019].

Dukic, D., McDonald, B., & Spaaij, R. (2017). Being able to play: Experiences of social inclusion and exclusion within a football team of people seeking asylum. Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2017, 5(2), 101–110. [online]. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i2.892 [Accessed 7 Oct 2018].

Ehrkamp, P. (2005). Placing identities: Transnational practices and local attachments of Turkish immigrants in Germany. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31(2), 345–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183042000339963. [Accessed 8 Dec 2019].

Erdal, M. B., & Oeppen, C. (2013). Migrant balancing acts: Understanding the interactions between integration and transnationalism. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39(6), 867–884. [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.765647 [Accessed 10 Nov 2019].

Ersbøll, E., & Gravesen, L. (2010). Country Report Denmark, The INTEC Project, European Integration Fund. [online] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/librarydoc/the-intec-project-integration-and-naturalisation-tests-the-new-way-to-european-citizenship---national-report-for-denmark [Accessed 19 Apr 2018].

Flüchtlingsrat, N. R. W. (2015). Flüchtlinge privat aufnehmen – darf ich das? Flüchtlingsrat Duisburg, Mittwoch, 2.12.2015. Flüchtlingsrat NRW e.V. [online]. Available at: http://docplayer.org/23422741-Fluechtlinge-privat-aufnehmen-darf-ich-das.html [Accessed 15 Apr 2018].

Freudenberg, J. (2018). Wohn- & Geschäftshäuser Marktreport 2018/2019 Leverkusen. Engel & Völkers Commercial Leverkusen. [online]. Available at: https://www.engelvoelkers.com/de-de/commercial/doc/Leverkusen_WGH_2018_2019_WEB.pdf [Accessed 3 Apr 2019].

George, S. (2004). Multi-level governance and the European Union. In I. Bache & M. Flinders (Eds.), Multi-level Governance (pp. 107–126). Oxford University Press.

Goodman, S. (2010). Integration requirements for integration’s sake? Identifying, categorising and comparing civic integration policies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(5), 753–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691831003764300. [Accessed 5 Dec 2017].

Goodman, S., & Wright, M. (2015). Does mandatory integration matter? Effects of civic requirements on immigrant socio-economic and political outcomes. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(12), 1885–1908. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1042434. [Accessed 5 Dec 2017].

Hanhörster, H., Droste, C., Lobato, I. R., Diesenreiter, C., & Liebig, S. (2020). Wohnraumversorgung und sozial räumliche Integration von Migrantinnen und Migranten Belegungspolitiken institutioneller Wohnungsanbietender. Bundesverband für Wohnen und Stadtentwicklung e. V. ISBN: 978–3–87941–802–2. [online]. Available at: https://www.vhw.de/fileadmin/user_upload/08_publikationen/vhw-schriftenreihe-tagungsband/PDFs/vhw_Schriftenreihe_Nr._16_Vergabepraktiken.pdf [Accessed 14 Jul 2020].

Haque, M. (2011). Non-governmental organizations. In M. Bevir (Ed.) The SAGE handbook of governance (pp. 330–341). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446200964.n21.

Homsy, G., Liu, Z., & Warner, M. (2019). Multilevel governance: Framing the integration of top-down and bottom-up policymaking. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(7), 572–582. [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2018.1491597 [Accessed 10 Jul 2019].

Hooghe, L., Marks, G. (2003). Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multilevel governance. American Political Science Review, 97. [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000649. [Accessed 22 May 2019].

Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Blank, K. (1996). European integration from the 1980s: State-centric v. multi-level governance*. Journal of Common Market Studies, 34, 3. September 1993. [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.1996.tb00577.x [Accessed 17 May 2019].

JOB Service Employment Promotion Leverkusen gGmbH. (2019). Willkommen im Quartier. [online]. Available at: https://www.joblev.de/leistungen/quartiersbezogene-angebote/willkommen-im-quartier/ [Accessed 13 Jun 2020].

Joppke, C. (2007). Beyond national models: Civic integration policies for immigrants in Western Europe. West European Politics, 30(1), 1–22. [online]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380601019613 [Accessed 3 Nov 2017].

Kjær, A. (2004). Governance. Polity Press.

Koos, S., & Seibel, V. (2019). Solidarity with refugees across Europe. A comparative analysis of public support for helping forced migrants. European Societies, 21(5), 704–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2019.1616794 [Accessed 20 Mar 2020].

Le Galès, P. (2011). Policy Instruments and Governance. In The SAGE Handbook of Governance, 142–159. SAGE Publications Ltd, 2011. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446200964.n10.

Lebedva, N., & Tatarko, A. (2004). Socio-psychological factors of ethnic intolerance in Russia’s multicultural regions. In B. N. Setiadi, A. Supratiknya, W. J. Lonner, & Y. H. Poortinga (Eds.), Ongoing themes in psychology and culture: Proceedings from the 16th International Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. [online]. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/243 [Accessed 10 Jan 2020].

Leverkusener Anzeiger. (2017). Flüchtlingsunterkunft: Alte Schule an der Görresstraße wieder frei. Kölner-Stadt Anzeiger. 02/10/2017. [online]. Available at: https://www.ksta.de/region/leverkusen/stadt-leverkusen/fluechtlingsunterkunft-alte-schule-an-der-goerresstrasse-wieder-frei-28518780 [Accessed 20 Jun 2018].

Löffler, E. (2000). Best-practice cases reconsidered from an international perspective. International Public Management Journal, 3(2), Winter 2000, 191–204. [online]. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7494(00)00035-0 [Accessed 3 Dec 2019].

Maroufi, M. (2017). Precarious integration: Labour market policies for refugees or refugee policies for the German labour market?, in D. Douhaibi, M. Aced, & C. Lee (Eds.). Refugee Review Special Focus Labour, Vol. III. [online]. Available at: https://espminetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Refugee-Review-Vol.-III.pdf [Accessed 7 Nov 2019].

Marsh, D., & McConnell, A. (2010). Towards a framework for establishing policy success. Public Administration, 88(2), 564–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01803.x [Accessed 3 Jul 2020].

McConnell, A. (2015). What is policy failure? A primer to help navigate the maze. Public Policy and Administration, 30(3–4), 221–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952076714565416 [Accessed 12 Jul 2020].

Meer, N., & Modood, T. (2012). How does interculturalism contrast with multiculturalism? Journal of Intercultural Studies, 33(2), 175–196. [online]. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2011.618266 [Accessed 27 Jan 2019].

Murdie, R. (2008). Pathways to housing: The experiences of sponsored refugees and refugee claimants in accessing permanent housing in Toronto. Journal of International Migration & Integration, 9, 81–101. [online]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-008-0045-0 [Accessed 2 Sept 2018].

Murphy, H. B. M. (1977). Migration, culture and mental health. Psychological Medicine, 7, 677–684. [online]. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/88AD333D34B0BB130C34F0223109DDBD/S0033291700006334a.pdf/migration_culture_and_mental_health1.pdf [Accessed 10 Jan 2020].

Nuissl, H., Domann, V., & Engel, S. (2019). Integration als kommunalpolitische Aufgabe. Die Erschließung eines sich neu formierenden lokalen Politikfeldes. Raumforschung und Raumordnung (published online ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.2478/rara-2019-0016 [Accessed 14 Apr 2019].

Phillimore, J. (2011). Approaches to health provision in the age of super-diversity: Accessing the NHS in Britain’s most diverse city. Critical Social Policy 0261–0183 101; 31(1), 5–29; 385437. [online] Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018310385437 [Accessed 25 Oct 2019].

Phillimore, J. (2012). Implementing integration in the UK: Lessons for integration theory, policy and practice. Policy & Politics, 40, 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X643795. [Accessed 2 Feb 2018].

Schillings, R., & Märtens, M. (2015). Das Leverkusener Modell. Stadt Leverkusen. [online] Available at: https://www.deutscher-verein.de/de/uploads/vam/2015/doku/f-9903-15/das_leverkusener_modell.pdf [Accessed 14 Apr 2018].

Scholten, P. (2013). Agenda dynamics and the multi-level governance of intractable policy controversies: The case of migrant integration policies in the Netherlands. Policy Sciences, 46, 217–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-012-9170-x. [Accessed 23 Nov 2019].

Sellers, J. (2011). State–society relations. In M. Bevir (Ed.) The SAGE handbook of governance (pp. 124–141). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446200964.n9.

Sert, D. (2012). Integration and/or transnationalism? The case of Turkish-German transnational space. Centre for Strategic Research, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Turkey. Volume XVII, Number 2, pp. 85–102. [online]. Available at: http://sam.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/deniz_sert.pdf [Accessed 13 Jan 2019].

Söhn, J. (2013). Unequal welcome and unequal life chances: How the state shapes integration opportunities of immigrants. European Journal of Sociology, 54, 295–326. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975613000155. [Accessed 23 May 2018].

Stadt Leverkusen, Dezernat für Bürger, Umwelt und Soziale. (2017). Sachstandsbericht Flüchtlinge in Leverkusen. [online] Available at: https://integration-in-leverkusen.de/images/PDF/Sachstandsbericht_Fluechtlinge_5_Maerz_2017.pdf [Accessed 18 Apr 2018].

Stadt Leverkusen Kommunales Integrationszentrum. (2017). Integrationskonzept der Stadt Leverkusen. [online] Available at: https://www.leverkusen.de/leben-in-lev/downloads/soziales/Broschu_re_Integrationskonzept_Leverkusen_ANSICHTSPDF_FINAL.pdf [Accessed 16 Apr 2018].

Stadt Leverkusen Kommunales Integrationszentrum. (2019). Umsetzungsbericht zum Integrationskonzept der Stadt Leverkusen. [online]. Available at: https://www.leverkusen.de/leben-in-lev/downloads/soziales/2019-07-01_Umsetzungsbericht_Integrationskonzept_Stadt_Leverkusen.pdf [Accessed 21 Jun 2020].

Stephenson, P. (2013). Twenty years of multi-level governance: Where does it come from? What is it? Where is it going? Journal of European Public Policy, 20(6), 817–837. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.781818. [Accessed 5 Mar 2019].

Vertovec, S. (2009). Transnationalism. In G. T. Kurien & J. E. Alt (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of political science (pp. 1683–1684). CQ Press.

Vey, J. (2018). Leben im Tempohome. Qualitative Studie zur Unterbringungssituation von Flüchtenden in temporären Gemeinschaftsunterkünften in Berlin. Zentrum Technik und Gesellschaft, Technische Universität Berlin, discussion paper Nr. 40/2018. [online]. Available at: https://www.tu-berlin.de/fileadmin/f27/PDFs/Discussion_Papers_neu/discussion_paper_Nr._40_18.pdf [Accessed 8 Aug 2018].

Vromen, A. (2010). Debating methods: Rediscovering qualitative approaches, in Marsh, D. & Stoker, S. (Eds.). Theory and Methods in Political Science: Third Edition, Palgrave Macmillan.

Zapata Barrero, R. (Ed.). (2015). Interculturalism in cities: Concept, policy and implementation. Edward Elgar.

Funding

The author received partial financial support from the University of York.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The author was granted by the University of York Ethics Board.

Disclaimer

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Auslender, E. Multi-level Governance in Refugee Housing and Integration Policy: a Model of Best Practice in Leverkusen. Int. Migration & Integration 23, 949–970 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00876-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00876-4