Abstract

Between 2015 and the beginning of 2016, Greece became one of the epicenters of the European migrant crisis as it was one of the major entry points by the sea of thousands of refugees entering its territory en route to wealthier countries. The unpreparedness of the Greek state and the European Union leaders to deal with the massive migrant flows significantly contributed to the pivotal role that informal and formal actors, including civil society migrant organizations, played to respond to migrants’ needs. The article using data from the EU-funded TransSOL project and applying a mixed method approach with the rationale of complementarity explores attributes (such as organizational structure, main activities, ultimate aims and means to achieve them, collaborative networks, etc.) as well as unveils the meaning of solidarity initiatives of specific formal and informal migrant organizations operating in the country. The indicative findings provide some preliminary evidence on the distinct features of informal and formal migrant organizations uncovering their diverse roles and tasks in meeting migrants’ needs and rights in Greece. It is recommended that further research on migrant organizations examining their main features and potential challenges in supporting migrants is essential not only for migrants themselves but for the whole society, specifically in times marked by a refugee crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The term “refugee,” as per international law, refers to someone who has been forced to flee his/her home country and is unable or unwilling to return to it due to fear of persecution. The term “asylum seeker” refers to an individual seeking protection in the country they are in. In a typical asylum claim process, an asylum seeker makes a claim for protection and waits for the relevant state to recognize him/her as a refugee or not. Not every asylum seeker will ultimately be recognized as a refugee, but every refugee is required to lodge an asylum application. Since some rejected asylum seekers may be refugees, the term refugee is used in the article to refer to both to asylum seekers and refugees. Moreover, the general term “migrant” is used in the article to denote an individual who changes his or her country of usual residence, irrespective of the reason for migration or legal status.

Almost one out of three first time asylum seekers originates from Syria, whereas top citizenships also include Afghans and Iraqis.

The drastic growth of legal and undocumented migrants in Greece, among others, is due to the overall geopolitical changes in the Balkan region, the country’s geographical position and geophysical structure as well as its economic growth due to its membership to the European Economic Communities in 1981 (Kasimis 2012).

Throughout the article the term “migrant organizations” is used to denote organizations that are run from natives and aim to support the rights of migrants residing in the country.

More information about the project can be found at: http://transsol.eu/

Civil society is an elusive and ambiguous concept that is difficult to define. In the present article, the term is used to denote “the totality of social institutions and associations, formal as well as informal, that are not strictly orientated towards production, and are not governmental or familial in character” (Odmalm 2004, p. 472).

Centre for Civil Society, Report on Activities July 2005–August 2006, London School of Economics and Political Science, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/29398/1/CCSReport05_06.pdf. Accessed 7 March 2019.

The sequential explanatory design is a two-phase design where the quantitative data is collected first followed by the qualitative data collection.

A TSO is defined as “a collective body/unit which organizes solidarity events with visible beneficiaries and claims’ on their economic and social well being – including basic needs, health, and work, as depicted through the TSO website/online sources” (TransSOL 2016, p. 282). More information for the quantitative method applied and the Codebook used can be found in TransSOL’s relevant report (see, TransSOL 2016).

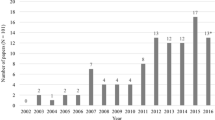

The 300 randomly chosen TSOs to be coded were selected only if they were active at any time at least between 2007 and 2016. Excluded from the sample are (a) state (central)-related organizations as sole organizers of alternative action, (b) EU-related organizations as sole organizers, and (c) corporate-related organizations as sole organizers of alternative action.

More information for the qualitative method applied and the guidelines for the in-depth interviews can be found in TransSOL’s relevant report (see, TransSOL 2016).

See Interview no. 3, no. 4, and no. 5 in Findings section.

See Interview no. 1, no. 2, and no. 6 in Findings section.

Using specific variables from the study’s Codebook, collaborative partners are grouped into six categories including (a) informal collaborators (such as informal citizens/grassroots groups, solidarity/social economy initiatives, indignados/occupy protests/movements, neighborhood assemblies etc), (b) formal collaborators (such as formal social economy enterprises, NGOs/volunteer associations, labor organizations, charities/foundations, associations, etc.), (c) private collaborators (such as companies/private business/enterprises, banks), (d) institutional national collaborators (such as local/regional/state related partners, political parties, church), (e) institutional international collaborators (including EU agencies/organizations/intergovernmental organizations), and (f) other international partners (including international agencies such as UN, WHO, ILO, etc.)

Using specific variables from the study’s Codebook, the beneficiary type of “Children/young people” includes children, youth/teens and students, of “Families/parents” includes families, parents, mothers, fathers, single parents, of “Health vulnerable individuals/groups” includes disabled and health-inflicted and health vulnerable groups (e.g., substance abuse persons), of “Socio-economic vulnerable individuals” includes poor/economically vulnerable/marginalized communities, poor/economically vulnerable/marginalized persons, imprisoned, homeless and uninsured. It should be noted that the above types of beneficiaries are not mutually exclusive.

It should be noted that the majority of Greek legislation about policy issues is predefined by the Memoranda (i.e., the economic adjustment programs implemented in Greece by the IMF, the European Commission and the European Central Bank) whereas policies specifically about migration are mainly decided at EU level.

References

Afouxenidis, A., Petrou, M., Kandylis, G., Tramountanis, A., & Giannaki, D. (2017). Dealing with a humanitarian crisis: Refugees on the eastern EU border of the island of Lesvos. Journal of Applied Security Research, 12(1), 7–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361610.2017.1228023.

Ambrosini, M., & Van der Leun, J. (2015). Introduction to the special issue: Implementing human rights: Civil society and migration policies. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 13(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2015.1017632.

Bagavos, Ch., Papadopoulou, D., & Symeonaki, M. (Eds.) (2008). Migration and service provision to immigrants in Greece. Research no. 29. Athens: INE/GSEE-ADEDY [in Greek] https://www.inegsee.gr/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/files/MELETH_291.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2018.

Cantat, C. (2018). The politics of refugee solidarity in Greece: Bordered identities and political mobilization. Hungary: Center for Policy Studies/CEU https://cps.ceu.edu/sites/cps.ceu.edu/files/attachment/publication/2986/cps-working-article-migsol-d3.1-2018.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2018.

Clarke, J. (2013). Transnational actors in national contexts: Migrant organizations in Greece in comparative perspective. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 13(2), 281–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2013.789672.

de Montclos, M.-A. P. (2007). Humanitarian NGOs and the migration policies of states: A financial and strategic analysis. In M. Korinman & J. Laughland (Eds.), The long marsh to the west (pp. 56–65). London: Vallentine Mitchell Academic.

Eggert, N., & Pilati, K. (2014). Networks and political engagement of migrant organisations in five European cities. European Journal of Political Research, 53(4), 858–875. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12057.

European Commission, (2016). Greece. Brussels: European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations. https://ec.europa.eu/echo/where/europe/greece_en. Accessed 8 Aug 2018.

Eurostat, (2016). Record number of over 1.2 million first time asylum seekers registered in 2015. Eurostat Newsrelease (44/2016 - 4 March 2016). http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7203832/3-04032016-AP-EN.pdf/790eba01-381c-4163-bcd2-a54959b99ed6. Accessed 23 July 2018.

Ferreira, S. (2006). The South European and the Nordic welfare and third sector regimes—how far were we from each other? In A.-L. Matthies (Ed.), Nordic civic society organisations and the future of welfare services. A model for Europe? (pp. 301–326). Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (2008). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation design. In V. L. Plano Clark & J. W. Creswell (Eds.), The mixed methods reader (pp. 121–148). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Gropas, R., & Triandafyllidou, A. (2009). Immigrants and political life in Greece: Between political patronage and the search for inclusion. Policy Brief for EMILIE project. Athens: Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.541.4208&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed 4 July 2018.

Harokopio University. (2009). Guide to NGOs and migrant associations: Profile of organizations in Greece active in migration issues. Athens: Department of Geography, Harokopio University [in Greek].

Huliaras, A. (2015). Greek civil society: The neglected causes of weakness. In J. Clarke, A. Huliaras, & D. Sotiropoulos (Eds.), Austerity and the third sector in Greece: Civil society at the European frontline (pp. 9–28). London: Ashgate.

IOM. (2008). Migration in Greece: A country profile 2008. Geneva: International Organization for Migration http://iom.hu/PDF/migration_profiles2008/Greece_Profile2008.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2018.

Kantzara, V. (2014). Solidarity in times of crisis: Emergent practices and potential for paradigmatic change. Notes from Greece. Studi di Sociologia, 3, 261–280.

Kasimis, C. (2012). Country profiles: Greece: Illegal immigration in the midst of crisis. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute http://www.migrationinformation.org/Profiles/display.cfm?ID=884. Accessed 28 June 2018.

Kavoulakos, K.I. (2006). Migrant organisations: Forms of claiming rights. Article presented in IMEPO Conference, Athens, 23–24 November [in Greek].

Kavoulakos, K., & Gritzas, G. (2015). Social movements and alternative spaces in Greece during the crisis: A new civil society. In N. Demertzis & N. Georgarakis (Eds.), The political portrait of Greece: Crisis and degradation of the political (pp. 338–355). Athens: Gutenberg [in Greek].

Kousis, M., Kalogeraki, S., Papadaki, M., Loukakis, A., & Velonaki, M. (2016). Alternative formen von resilienz in Griechenland. Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen, 29(1), 50–61 [in German].

Kousis, M., Kalogeraki, S., Papadaki, M., Loukakis, A., & Velonaki, M. (2018a). Confronting austerity in Greece: Alternative forms of resilience and solidarity initiatives by citizen groups. In J. Roose, M. Sommer, & F. Scholl (Eds.), Europas Zivilgesellschaft in der Wirtschafts- und Finanzkrise (pp. 77–99). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Kousis, M., Giugni, M., & Lahusen, C. (2018b). Action organisation analysis: Extending protest event analysis using hubs-retrieved websites. In M. Kousis, S. Kalogeraki, & C. Cristancho (Guest Editors), Alternative action organisations during hard economic times: A comparative European perspective. Special issue in American Behavioral Scientist, 62 (6), 739–757, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218768846

Leontsini, M. (2010). Migrant women’s organizations in Athens and multicultural democracy: Gender, social capital and social cohesion. Athens: Department for Early Childhood Education.

Loukakis, A. (2018). Not just solidarity providers. Investigating the political dimension of alternative action organisations (AAOs) during the economic crisis in Greece. In S. Kalogeraki (Ed.), Socio-political responses during recessionary times in Greece, Special issue in Partecipazione e Conflitto, 11(1), 12–37, https://doi.org/10.1285/i20356609v11i1p12.

Loukidou, K. (2013). Formal and informal civil society associations in Greece: Two sides of the same coin? Greek Politics Specialist Group (GPSG) Working Article no. 13. http://www.gpsg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Working_Article_13.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Loukidou, K. (2014). New examples of collective action in Greece: Challenging the traditional patterns of civil society-state relationship. Article presented at the 11th ISTR International Conference Civil Society and the Citizen, Muenster, 22–25 July.

Lyrintzis, C. (2002). Greek civil society in the 21st century. In P. C. Ioakimidis (Ed.), Greece in the European Union: The new role and the new agenda (pp. 90–99). Athens: Ministry of Press and Mass Media.

Mouzelis, N. (1995). Modernity, late development and civil society. In J. A. Hall (Ed.), Civil society: Theory, history, comparison (pp. 224–249). Cambridge: Polity Press & Blackwell publishers Ltd.

Odmalm, P. (2004). Civil society, migrant organisations and political parties: Theoretical linkages and applications to the Swedish context. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(3), 471–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830410001682043.

Oikonomakis, L. (2018). Solidarity in transition: The case of Greece. In D. della Porta (Ed.), Solidarity mobilizations in the ‘refugee crisis’ (pp. 65–98). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Papadaki, Μ., & Kalogeraki, S. (2017). Social support actions as forms of building community resilience at the onset of the crisis in urban Greece: The case of Chania. In M. Kousis (Ed.), Alternative forms of resilience confronting hard economic times. A South European perspective, special section in PArtecipazione e COnflitto, 10(1), 193–220.

Papadaki, M., Alexandridis, S., & Kalogeraki, S. (2015) Community responses in times of economic crisis: Social support actions in Chania, Greece. Kurswechsel: Zeitschrift für gesellschafts-, wirtschafts- und umweltpolitische Alternativen, 1: 41–50.

Papadopoulos, A., & Fratsea, L. (2017). The “unknown” associations of civil society: Immigrant communities and associations in Greece. Greek Political Science Review, 42, 62–90. https://doi.org/10.12681/hpsa.14570 [in Greek].

Papadopoulos, A., Chalkias, C., & Fratsea, L. (2013). Challenges of immigrant associations and NGOs in contemporary Greece. Migration Letters, 10(3), 271–287.

Papataxiarchis, E. (2016a). Being “there”: At the front line of the “European refugee crisis”—Part 1. Anthropology Today, 32(2), 5–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8322.12237.

Papataxiarchis, E. (2016b). Being “there”: At the front line of the “European refugee crisis”—Part 2. Anthropology Today, 32(3), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8322.12252.

Papataxiarchis, E. (2016c). A big reversal ? The European refugee crisis and the new patriotism of ‘solidarity’. Sychrona Themata, 132–133, 7–28 (in Greek).

Petronoti, M. (2001). Εthnic mobilisation in Athens: Steps and initiatives towards integration. In A. Rogers & J. Tillie (Eds.), Multicultural policies and modes of citizenship in European cities (pp. 41–60). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Pilati, K. (2012). Network resources and the political engagement of migrant organisations in Milan. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(4), 671–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.640491.

Rozakou, K. (2011). The pitfalls of volunteerism: The production of the new, European citizen in Greece. European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies. http://eipcp.net/policies/rozakou/en. Accessed 2 Aug 2018.

Rozakou, K. (2016). Socialities of solidarity: Revisiting the gift taboo in times of crises. Social Anthropology, 24(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12305.

Sardinha, J. (2009). Immigrant associations, integration and identity: Angolan, Brazilian and Eastern European communities in Portugal. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Schaub, M. (2013). Humanitarian problems relating to migration in the Turkish-Greek border region: The crucial role of civil society organisations. Research Resources Article for COMPAS. Oxford: University of Oxford. https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/RR-2013-Fringe_Migration_Turkish-Greek.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2018.

Siapera, E. (2019). Refugee solidarity in Europe: Shifting the discourse. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 22, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549418823068.

Simiti, M. (2017). Civil society and the economy: Greek civil society during the economic crisis. Journal of Civil Society, 13(4), 357–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2017.1355033.

Skleparis, D. (2015). Towards a hybrid ‘shadow state’? The case of migrant-/refugee-serving NGOs in Greece. In J. Clarke, A. Huliaras, & D. A. Sotiropoulos (Eds.), Austerity and the third sector in Greece: Civil society at the European frontline (pp. 147–166). London: Ashgate.

Sotiropoulos, D. (2004). Formal weakness and informal strength: Civil society in contemporary Greece. Discussion Article No. 16, London: The London School of Economics and Political Science, Hellenic Observatory/The European Institute. http://www.lse.ac.uk/Hellenic-Observatory/Assets/Documents/Publications/Past-Discussion-Articles/DiscussionArticle16.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2018.

Sotiropoulos, D. (2014). Civil society in Greece in the wake of the economic crisis. Research Article. Athens: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) & Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy http://www.kas.de/wf/doc/kas_12986-1442-2-30.pdf?140522091732. Accessed 1 July 2018.

TransSOL, (2016). Integrated report on reflective forms of transnational solidarity. Deliverable 2.1. TransSOL: European paths to transnational solidarity at times of crisis: Conditions, forms, role models and policy responses. http://transsol.eu/files/2016/12/Integrated-Report-on-Reflective-Forms-of-Transnational-Solidarity.pdf. Accessed 7 July 2018.

Uba, K., & Kousis, M. (2018). Constituency groups of alternative action organizations during hard times: A comparison at the solidarity orientation and country levels. In M. Kousis, S. Kalogeraki, & C. Cristancho (Guest Editors), Alternative action organisations during hard economic times: A comparative European perspective. Special issue in American Behavioral Scientist, 62 (6), 816–836, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218768854

Varouxi, E. (2008). Immigration policy and public administration: A human rights approach of social actors and organisations of civil society. Working Papers 2008/17, Athens: National Centre for Social Research [in Greek].

Zachou, C., & Kalerante, E. (2009). Albanian civil associations in Greece: Ethnic identification and cultural transformations. In M. Pavlou & A. Skoulariki (Eds.), Migrants and minorities: Politics and discourse (pp. 457–494). Athens: Vivliorama [in Greek].

Funding

Results presented in this article have been obtained within the project “European paths to transnational solidarity at times of crisis: Conditions, forms, role models and policy responses” (TransSOL). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 649435. The TransSOL consortium is coordinated by the University of Siegen (Christian Lahusen), and is formed, additionally, by the Glasgow Caledonian University (Simone Baglioni), European Alternatives e.V. Berlin (Daphne Büllesbach), the Sciences Po Paris (Manlio Cinalli), the University of Florence (Carlo Fusaro), the University of Geneva (Marco Giugni), the University of Sheffield (Maria Grasso), the University of Crete (Maria Kousis), the University of Siegen (Christian Lahusen), European Alternatives Ltd. LBG UK (Lorenzo Marsili), the University of Warsaw (Maria Theiss), and the University of Copenhagen (Hans-Jörg Trenz).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kalogeraki, S. A Mixed Method Approach on Greek Civil Society Organizations Supporting Migrants During the Refugee Crisis. Int. Migration & Integration 21, 781–806 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-019-00689-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-019-00689-6