Abstract

Informal settlements in major urban areas are often derided through discourses as pockets of poverty, disorder, and marginalisation. Consequently, city planning officials often seek to eliminate or reduce such settlements for more ordered planned settlements. Yet, informal urban settlements continue to remain a part of urban life and have, in many places, increased in size and density. This paper provides an ethnographic account of the place-making activities deployed by informal settlement dwellers in Abuja, Nigeria, who face constant threats of displacement and eviction. We use place-making as an analytic lens with which to explore the discursive, political, and material strategies used by individuals and communities to resist the threats of displacement. Through ethnographic fieldwork in Mabushi and Mpape, we identify, on the one hand, the key material strategies of place-making to include incremental improvement to dwellings, planting of economic trees, and physical confrontations. On the other hand, the formation of settlement associations and active involvement in local politics with its attendant alliance-making have contributed to place-making strategies through the development of meanings, senses of togetherness, and belonging to the settlements. Our findings show the agency of informal settlement dwellers and how they use both material processes and discursive narratives to generate new meanings of place, tenure security, and the right to the city. This enables them to resist displacement from the urban environment. We conclude that a place-making approach to exploring informal settlements is fruitful for understanding the complexity of urban change processes in the Nigerian context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

On the 2nd of February 2017, jubilant residents in the sprawling informal settlement of Mpape in Abuja, Nigeria, poured out on the streets in celebration. This was the day an Abuja High Court judge ruled that the planned demolition and eviction of the settlement by the Federal Capital Development Authority (FCDA) was illegal, and therefore had to be abandoned. This famous legal victory against urban demolition of the settlement came as relief to the thousands of residents in Mpape who for so long had lived in a state of fear under constant threats of demolition from city planning authorities. In July 2012, the FCDA and its Department of Development Control served the residents of Mpape with notices to quit as part of the planned demolition of the settlement. According to the residents, the FCDA’s action was without any prior consultation or provision for alternative housing options or compensation. It was on this basis that members of the Mpape Residents Community Development Association (MRCDA) with the help of local and international non-governmental organisations headed to the High Court to seek for a revocation of the notices to quit from the FCDA. In addition to arguing that the FCDA was in breach of international laws prohibiting forced eviction, the MRCDA also argued that many of the residents of Mpape had lived there for decades — some even long before Abuja became a Federal Capital City in 1976 — and so have accrued rights to adequate housing and land tenure security. It took nearly 5 years of legal tussle before the court ruled against demolition and declared it an illegal process that could not proceed. Since this legal victory, residents of informal settlements in Mpape and other peripheral areas of Abuja have continued pursuing place-making strategies to secure their existence in the urban space. This situation goes against the vision of making Abuja a befitting modern capital of Nigeria through strict planning enforcement, in line with the Federal Capital Territory Act of 1976. Existing informal settlements were evicted, displaced, and relocated to make way for well-planned and regulated urban development. However, more than 45 years later, informal settlements remain a key part of Abuja’s urban landscape. The persistence of informal settlements in Abuja raises thought-provoking questions about how these informal settlements manage to survive attempts to evict them, and what different strategies the dwellers use to secure their land tenure while facing constant threats of displacement.

In the context of the ongoing rapid pace of global urban transition, it is estimated that approximately 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas (United Nations, 2018). In Africa, the population is set to double to 1.3 billion by 2050 with an accompanying high rate of urbanisation resulting in pressures on land and other resources. The number of people living in informal settlements is expected to increase sharply because new urban migrants can access cheap accommodation and find employment opportunities (Stacey, 2018). Often, informal settlements are established on lands that formally belong to either the state or other people. This situation makes the issue of land rights and tenure security contentious for urban planners and informal settlement dwellers who have to constantly fight against threats of eviction. Nigeria, home to the largest population in Africa, is faced with a dramatic urban transition across many cities. This urban process places pressure on critical social services, resulting in urban planning and policy challenges in the country (Onwujekwe et al., 2022). Fabiyi (2017) argued that the growth of informal settlements in Nigerian cities and difficulties in their effective governance are due to weak urban administration policies that are inconsistent in formulation and implementation. However, what is often missing in such accounts is how residents in urban informal settlements fend of attempts at urban planning processes that tend to sweep the poor away (Watson, 2009). Informal settlements remain rooted in the urban landscape as places of diversity and ingenuity, as dwellers adopt creative ways to survive with minimal resources. The residents’ place-making activities in Nigeria’s informal settlements need to be seen as residents’ ways of securing their own well-being in a contested space by maintaining secure access to prime urban lands. It is in this context of contestations over access to urban space that the informal settlements of Mpape and Mabushi have taken root in Abuja.

Therefore, this study provides an ethnographic account of place-making activities deployed by informal settlement dwellers in Abuja, Nigeria, who face constant threats of displacement and eviction. We use place-making as an analytic lens with which to explore the discursive, political, and material strategies used by individuals and communities in resisting the threats of displacement. This paper is structured into six sections as follows. After this introduction, the next section develops a conceptual framework of perceived tenure security through place-making approaches. The third section focuses on the research design, methodology, and methods. The findings on the material and discursive meaning approaches to place-making are structured into the fourth and fifth sections, respectively. The final section presents a discussion of the key insights leading to the final conclusions.

Perceived Tenure Security: a Place-Making Approach

All controversies around informal settlements — settlements that fall out of the government’s official regulation and protection — are invariably tied to land ownership rights and the tenure security of the dwellers. Land rights, defined as the social and legal entitlement to acquire, use, and control a piece of land (UN-Habitat, 2008:5), are the main contentious issue in discourses on informal settlements (Roy, 2005). Contention over land rights in informal settlements is often connected to disagreements over different land ownership claims and tenure arrangements. Land tenure — the institutional and legal framework for regulating land-use behaviour, property rights, accessibility, allocation, control, transfer, usage type, and period of use (FAO, 2002; Malik et al., 2019) — is a form of formal protection from arbitrary displacement or forced eviction from city authorities. However, tenure security, namely, the guarantee of protection from arbitrary displacement and confidence that one’s right to a land is recognized by others and protected by all authorities (United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation FAO, 2002:29), defines the dynamics around informal settlements (Malik et al., 2019; Reale & Handmer, 2011). Normally, the one with the officially recognized (statutory) right to a land should have higher tenure security, but in cases where other unofficially recognized persons already have access to the land, tenure insecurity starts manifesting for both the official and unofficial land claimers. The contentions over land ownership rights increase tenure insecurity because of the awareness of all land rights claims that a change in the rules of engagement can alter the access and utility of the land (see Arnot et al., 2011).

The challenges of land rights and tenure security and related secondary challenges, such as infrastructural development, are persistent problems for informal settlement dwellers (ISD), which constitute up to 70% of the urban population in Africa. The urban land issues in most African cities are complex, multi-layered, and poorly understood because of the complex powerplay, lack of transparency, institutional challenges (Berry, 2009; Hornby et al., 2017; Nuhu, 2018; Otubu, 2018), unending land crises, and conflicting claims on land rights and tenure security (van der Haar et al., 2020). Conflicting claims and contentions often originate from different tenure arrangements: the (postcolonial) state’s formalized statutory tenure arrangements and preexisting customary arrangements. These two — customary and statutory land rights or tenure practices — are the most common normative classes of land rights and tenure security. Customary land tenure practices are based on local, traditional, or ancestral customs or communal land management (Hornby et al., 2017). It is the dominant or widely accepted tenure practice across sub-Saharan Africa, under the authority of traditional rulers (Chimhowu, 2019). Statutory land tenure is commonly described as an adopted land management practice by colonial masters, where the state has the overriding rights to allocate and register land based on the state’s land use plans (see Njoh, 2013).

Despite most postcolonial states adopting the statutory tenure system, customary land practices are still prevalent in many African societies, especially indigenous communities whose indigeneity is a source of land security (Sjaastad & Bromley, 1997). However, between the two classes of tenure practices, de facto tenure practices define the dynamics of land in most African cities. There are questions regarding what is legal or illegal, temporary or permanent lease, registered or unregistered, community or individual ownership, indigenous or state lands, etc. (see Hornby et al., 2017; UN-Habitat, 2008; Sjaastad & Bromley, 1997) in African land dynamics. Even though informal settlement dwellers are always subjected to (threats of) displacement, they are considered to have de facto tenure security because of their current occupation or entitlement to the land (van Gelder & Luciano, 2015). Their de facto tenure security does not prevent displacement, but they usually deploy different ways to enhance their security.

In this study, we aim to contribute to the expanding literature on land rights and tenure security by exploring the ways in which informal settlement dwellers of Abuja engage in place-making strategies to strengthen their tenure security under the threat of displacement and eviction. Van Gelder and Luciano (2015) argued that tenure security has three forms. First, there is the de facto tenure security that accrue to people based on ancestral ties to a place and/or due to their indigeneity. Second, there is perceived tenure security, that is, the subjective perception of individuals or groups on their security or protection from arbitrary displacement, often based on having lived in a given place for a long time. Third, there is legal tenure security, which is tenure security according to existing laws and legislation. Using the case of low-income settlements in Durban, South Africa, Patel (2013) explained that dwellers understood and realized their tenure security differently from the statutory rights imposed by the state. These differences, she argues, need to be captured or operationalized in theories and policies, and mainly in state dealings with informal settlement dwellers. The management of informal settlements is often a yardstick for evaluating the efficiency of the state and its planning institutions in many global south cities. In addition, the socio-economic systems that produce urban inequality and marginalisation of the urban poor, urban planning and regulatory institutions that designate what space is formal or informal, and the institutions that enhance the emergence of informal settlements are all connected to the working mechanisms of the state (Alfaro d’Alençon et al., 2018; Roy, 2005; Wacquant, 2008, 2015). The unpredictable actions of the state and the persistent threats of displacement make the everyday lives of informal settlement dwellers precarious and vulnerable.

This paper is an ethnographic study on the linkages between the social and the spatial aspects of resistance practices in contexts of perceived tenure security. Resistance practices of dwellers can ensure that they are not arbitrarily displaced (Arnot et al., 2011; Hall et al., 2015; Michelutti & Smith, 2014; Reerink & van Gelder, 2010; Rubin, 2018; van Gelder & Luciano, 2015). Research has also shown that studying the resistance of people and groups in relation to the places where it occurs is fruitful (Courpasson & Vallas, 2016; Courpasson et al., 2017). The aim of this study is to demonstrate how resistance to displacement occurs in and through place(-making strategies) and how place is both an enabling and constraining factor in resistance practices.

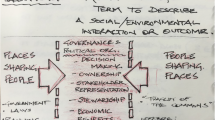

There are many types of place-making strategies, ranging within and beyond the dichotomies of top-down and bottom-up, formal and informal, or formal planning and citizen-led place-making (Andres et al., 2021). Top-down and formal place-making refer to the collaborative effort of state and non-state institutions with the aim of crafting the physical characteristics, functions, and meanings of a place. It is commonly associated with the collaborative work of planners, policymakers, and architects, and it ignores the activities of dwellers in the making of places. Bottom-up or informal place-making refers to the actions of the dwellers as place-makers and the ways they use place to address their social realities in informal settlements. This relates to what Quintana Vigiola (2022) calls “people-centred approaches,” which emphasize the role of the people in transforming a place to address their needs. Place-making is used here to capture the efforts of dwellers to organise, arrange, and give meaning to their everyday places in relation to or as a response to persistent threats of displacement. We see place-making as a political endeavour and draw attention to the choices people make in the making of a place to achieve a certain goal, what the effects are of their place-making activities, and how they address the wider context of the city and the country. As Lombard (2014) argues, place-making offers a fruitful perspective on resistance as it cuts across different scales, from individuals to groups and families, from private to public spaces, and from smaller-scale places and neighborhoods to wider areas. Contributing to ethnographic work on marginalised places, we emphasise the agency of the dwellers in making a change and claiming their right to the city (Lefebvre, 1968), while being aware that their agency is deeply constrained by legal and economic circumstances, often unfavourable for them, both at the city and at the state level. Our approach relates to what Andres et al. (2021) called “citizen-led place-making” to refer to the “reactive alternative-substitute place-making that occurs when there is no available alternative” (p.29). As Andres et al. (2021) argue, planning in the Global South needs to include a more complex and systemic framework that incorporates also “impermanent, adaptable, temporary and alternative forms of place-making into the planning process for regional futures” (p.29).

The nature of informal settlement dwellers’ emotional relationships with places is relevant to our understanding of place-making activities as strategies to resist displacement. The particular ways in which places are meaningful for people have been explored in debates that have unfolded around the concepts of place attachment and sense of place, among others. Place attachment refers to the emotional bonds between people and places (see Manzo & Devine-Wright, 2014; Altman & Low, 1992; Lewicka, 2011a, 2011b). Such approaches deal primarily with the “person component” (Lewicka, 2011b), and they have been most commonly explored through positive experiences of the dwellers and the places that are meaningful to them (Manzo, 2005). By focusing on place-making, we want to emphasise that the dwellers in informal settlements do not only form attachments to place in contexts of persistent threats of displacement. Rather, they craft the meanings and functions of a place to achieve political goals and, in this case, to strengthen the security of their land tenure. We apply this place-making approach to capture the idea of place as a process, always in the making (Massey, 1991, 2005), and more importantly, to demonstrate that place is “a way of seeing, knowing, and understanding the world” (Cresswell, 2004:11). Our approach to place-making and resistance practices contributes to the understanding of the complexity of urban processes in the Nigerian context.

Research Setting, Methodology, and Methods

Nigeria, located in Western Africa, provides a rich case setting for exploring issues around informal urban settlements. With an estimated 225 million people, it is the most populous country in Africa and the 6th most populous country in the world. As a republic, Nigeria has a mix of federal, presidential, and representative democratic system of governance. In this system, the national government holds executive power, while legislative power is wielded by the federal government and the two legislative chambers of the House of Representatives and the Senate. The country is divided into 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), in which the country’s capital, Abuja, is located. Given the growing urban governance issues in Lagos (the former capital city), a national decree (decree no. 6, FCT Act 1976) was promulgated on 4 February 1976 to establish a new national capital region which was carved out of the existing Kogi, Niger, Kaduna, and Nassarawa states. The larger Abuja metro area and the city of Abuja, with a current estimated population of over 3.6 million, became the new national capital region and capital city, with land areas of approximately 8000 km2 and 250 km2, respectively.

The coming into force of the FCT Act in 1976 and the creation of Abuja as the FCT meant that all existing traditional customary land management processes, titles, and rights became void. All land allocation, control, and governance within this area came under the sole authority of the national state government through the FCT minister. Thus, the existing original inhabitants and communities were classified as informal and marked for displacement, relocation, and resettlement to make way for a more planned and regulated urban development process, making Abuja a befitting modern capital city of Nigeria. These informal settlements that existed prior to the creation of Abuja as an FCT were resettled in order to make way for a well-planned modern city. These plans have remained unrealised leading to the subsequent neglect of these informal settlements that have grown in size with a number turning into slums. Consequently, over 45 years later, the dream of a well-planned modernised city is yet to be realised amidst a growth in the size and form of urban informal settlements in Abuja. Over the past decades, Abuja has become a scene of constant face-off between city planning and governance authorities and the collective groups of urban informal dwellers amidst (threats of) demolitions, displacement, and contentiousness over resettlement compensation packages. Given such a situation, the question remains as to how dwellers in these informal settlements persist in their place-making activities to show their belonging and contribution to the city.

Research for this paper was carried out in the two neighborhoods of Mabushi and Mpape, located in the core and periphery of Abuja, respectively. Their different origins, sizes, locations, and socioeconomic and demographic statuses provide a unique basis for exploring the process of place-making by city dwellers. While a direct comparison is not sought in this research, findings from these two neighbourhoods provide insights that can deepen the understanding of the place-making creativity of urban informal settlements. Mpape is regarded as the biggest slum area in Abuja, situated within a practice and discourse of displacement and forced evictions, while Mabushi, given its central location in the city centre, has resettlement plans developed by federal state planning authorities.

The data were produced as part of a larger project aimed at the understanding of the ways in which the interactions between state and non-state actors influence land rights and tenure security in informal settlements in Abuja. The main methods were semi-structured interviews with state and non-state actors, focus group discussion, document analysis, and participant observations. The methodological design entailed three phases of fieldwork visits to over 1.5 years: March to April 2019, October 2019 to January 2020, and October and November 2020. State actors in this study refer to the state officials that are affiliated to state agencies and institutions and are having statutory roles of executing state’s policies and plan. Non-state actors refer to the other stakeholders without official affiliation, and who are either contending or reacting to state’s policies and plans. The non-state actors include out of office politicians or politicians without portfolio. The interview participants cut across relevant government agencies, departments, and units such as the Federal Capital Development Authority (FCDA), Abuja Geographic Information System (AGIS), Lands Department, Development Control Department (also known as Abuja Metropolitan Management Council-AMMC), and the Municipal Area Councils. The non-state participants include community leaders, representatives, and residents in Mpape, Mabushi, Jabi, Kpadna, Kabusa and Utako on one side, and self-proclaimed politicians (without portfolio), land developers, investors, agents, and individuals that have been allocated the lands of yet-to-be resettled indigenous communities. In total, 48 interviews and 10 focus group discussions were carried out with over 100 participants. An extensive review of relevant policies and documents was used to supplement the interview data. Policy documents, Abuja master plan, regional development plans, 1976 FCT Act, Nigerian Land use Act of 1978, and their reviews, research papers, maps, court cases, and media reports were sourced from government institutions such as FCDA, AMMC, AMAC, and AGIS.

In terms of positionality and ethics, the first author is a (anonymised) and a researcher in (anonymised). His position of being an insider and outsider enhanced and constrained access to research participants and information, hence the need for some reflexive practices to negotiate through hurdles (Adu-Ampong & Adams, 2019). For example, based on his understanding of the working mechanisms of most of the state institutions and clues from some insiders, he was able to informally negotiate most bureaucratic bottlenecks that would have limited his access to relevant informants and documents. One downside of this positionality is that some participants provided concise responses to questions assuming that as a (anonymised) with lived experience of the country’s governance processes, he should understand the situation without much explanation. However, this shortcoming was compensated for with interviews with more respondents within the same department or unit; this was to verify and/or supplement the responses of their colleagues.

Resisting Displacement Through the Materiality of Places and the Built Environment

Among its many conceptualisations, place is also a process — an open-ended process of becoming in which people’s agency and activities continuously shape the history and materiality of a given physical location (Massey, 1991, 2005). Within informal settlements, this conception of place as a process provides an essential framework for seeing informal settlement dwellers as agents who, although constrained by existing structures, still manage to act in ways that resist and disrupt their attempts to displace them. Through often quite incremental changes to the physical environment, informal settlement dwellers engage in place-making activities that seek to strengthen the security of their land tenure. Under the shadow of regular threats of displacement, the dwellers in Mpape and Mabushi continued to exhibit agency in securing their existence in Abuja. In this section, we highlight three main ways in which they resist displacement through material ways within the built environment.

The first place-making strategy used by dwellers in Mpape and Mabushi entails incremental improvements to their dwelling places. The state often attempts to displace these communities on the basis that they have old mud houses and practice traditional ways of life. To resist this charge and prevent the demolition of their structures, informal settlement dwellers are now stepping up to modernize their living conditions, especially by rebuilding their old houses to conform with modern structures using sand blocks. While it is easier for state planning agencies to demolish old mud houses — often in derelict conditions (see Fig. 1) — it is more difficult for them to pull down houses built with sand concrete blocks on the basis of structural and aesthetic reasons. By demolishing their own old mud houses and rebuilding them with modern materials (see Fig. 2), dwellers are able to counter the main justification of the state planning agencies to oust them from the urban area. This communal sentiment is expressed by a local political leader, who is also the owner of one of these modern concrete block houses in Mabushi:

…I started this structure in 2006, then my friends were warning me about the resettlement, I told them I can’t wait for FCDA any longer for a resettlement that will never happen…I am happy some of them are now doing the same, anybody that get little opportunity of money they demolish their house and start something…if you go up there you will see some (new) houses, that is because they have kept aside the hope of resettlement, we are the ones resettling (or reintegrating) ourselves now...

This strategy of local residents in putting up new concrete houses is their way of resisting displacement, knowing that it is very difficult for city officials to pull down such structures. City planning officials also attest to the efficiency of this resistance strategy, in which some residents modernise the inside of their dwellings through incremental changes. A senior planning official in the FCDA resettlement department noted the following:

…see, it’s because there is no space for them to develop. Did you enter the houses? They have modernized the inside; it is the outside that is looking so tattered, most of them have AC [air conditioning] in their houses, sometimes even prefer to stay in those places not minding the environment; when you begin to look at them like that [from the modernizing perspective], they are not slum per se… (see also Fig. 3).

The process of improving their dwellings on both the outside and inside is a clear place-making strategy that serves to strengthen the dwellers’ claim to tenure security and provide a resistance buffer to attempts to displace them.

A second material practice of resisting displacement through place-making involves the planting of economic trees such as cashews and moringa on vacant land spaces in the communities and in surrounding farmlands. Place-making strategies, both formal and informal, involve not only changes in the urban infrastructure and built environment but also in the green spaces in the city. Similar to modern concrete block houses, it is difficult for city officials to displace communities with a high number of planted economic trees. This is because there is a legal stipulation that compensation is paid for all economic trees that have to be cut down to make way for any statutory land claimant or developer to access the land. During interviews, developers, surveyors, and land agents reported that they had to pay huge amounts of money for economic trees before they could access the lands that had been statutorily allocated to them. A land agent and developer noted the following:

…we pay for cashew trees, moringa trees, palm trees, …sometimes we can pay as much as 4 million naira (about 7000euros) per hectare…officially it’s supposed to be 1500 naira [about 3euros] per tree for the nursery ones, 3000 (about 6euros) for those that are producing, 17000 [about 30euros] for cashew trees, but if we pay through the government, they won’t get the money, so it’s better to bargain with them [the dwellers] directly…

Indeed, while the legal requirement for compensation for economic trees sets the rates, this is not always adhered to by actors involved due to government bureaucracy. Therefore, developers resort to direct negotiations with informal settlement dwellers for compensation payments. Thus, dwellers who seek to hold tightly to their place tend to demand exorbitant compensation for economic trees. This deters potential developers from attempting to displace them, and continues to prove an effective resistance strategy.

Physical confrontation and sometimes acts of vandalism represent the third main resistance strategy used by the dwellers in Mabushi and Mpape. The materiality of this strategy involves protests, road blockages, and confrontational attacks, which are commonly used to resist displacement and land confiscations in informal settlements. During a court case instigated after the state attempted to demolish a significant part of the informal settlement in Mpape, residents reported that they blocked the road on the judgement day to swing the court’s judgement in their favour. According to the Mpape youth leader:

…we closed down Mpape on the judgement day, all the students didn’t go to school, we all went to the court…and that helped because they already asked the judge to approve the demolition, but when they saw all of us on the street, vehicles couldn’t move until the judgement went in our favor…

The question is whether it was indeed their protests on the day that swung the judgement. What is significant is the belief held within informal settlements that protests represent an avenue of place-making and resistance strategies. In addition to protests, informal settlement dwellers use physical confrontation to resist displacement. In Mabushi, the traditional council explained that their youth usually chase away development control officials at any time they come to their communities. Land developers also attest to physical confrontations with informal settlement dwellers. One land agent interview said: “…they [the dwellers] can shoot an arrow at you from the bush if you don’t consult them or go to the plot without an indigene or the owner of the land….” Furthermore, the traditional leaders explained that the last time Abuja city officials came with the military in trying to forcefully demolish their houses, they all went inside their houses and challenged the officials to demolish their houses while staying inside. Such physical confrontations usually result in city officials and developers abandoning demolition attempts.

Making Resilient Places: Meanings, Actions, and Senses of Togetherness

Place-making not only captures the efforts of dwellers to craft the material characteristics and functions of a place but also shapes its meanings for the dwellers and outsiders. To the outsiders, both Mpape and Mabushi now appear as united places where city dwellers have a strong sense of togetherness and organized resistance efforts. The dwellers of Mabushi have formed associations at the community level and are part of various organisations such as the Nigerian Slum/Informal Settlement Federation, the Association of Abuja Indigenous Communities, the FCT Youth Coalition, and other community-based associations. According to the Mabushi community council, during a focus group discussion, most of the associations were formed “because of the forceful collection of lands without due process.” Mpape residents also have an association (“Mpape residents’ association”) that is legally registered with the state. According to a tribal head in Mpape, the “residents’ association is legally registered (because) we are trying every means possible to counter any move they want to come with, we know the laws they are coming to quote for us.” The activities of the associations are also supported by several media platforms (such as WhatsApp and Facebook) to create awareness and mobilize their members across Abuja for any action of resistance.”

The increased sense of togetherness and joint concern has resulted in solidarity among dwellers. The common areas of solidarity among the majority of the dwellers are their unity in sourcing resources for community development and cooperation to enhance peace in the communities. As dwellers are deprived of basic amenities from the state, most of the amenities they have in their communities are a result of community efforts. As unity among the dwellers is crucial for their survival, no major lines of division along religious or tribal lines exist among the dwellers, as the tribal head of the Hausa migrants described:

…there is no tribalism and no religion crisis between the Muslim and the Christians, we have been living peacefully, and we the leaders are not showing any religious difference, the leader [Mpape traditional ruler] does not discriminate. Anytime any issue comes up we have support from our neighbours too to maintain our togetherness…

However, lines of division and conflicts exist. Rapid urbanisation across the country has resulted in major rural–urban migration. This created a situation in which migrants of similar tribes could not be differentiated from their original inhabitants for developmental planning purposes (especially resettlement). The indigenous and non-indigenous dichotomy manifests in some important issues concerning the community, such as financial contributions to community projects, demolitions, and tenure security. The indigenous and non-indigenous differences are also manifested in the demolition of illegal houses and the tenure security of some informal settlement dwellers. Most respondents revealed that migrants were the main targets of the state’s demolition exercises. The indigenes are confident that they are safe and protected because of their indigenous status of having customary or ancestral rights to their land. Apart from the different classes of some informal settlement dwellers (indigenes and non-indigenes) that could sometimes be a source of conflict, there are some stakeholders who have other interests that influence the overall stability of informal settlements. These conflicting interests are usually between community leaders (traditional chiefs) and political (administrative) representatives within and outside informal settlements. Such parallel interests include the struggle for community leadership (that is, who represents the dwellers), the conniving of actors with state officials and developers to grab land, and the hijacking of development funds and support from the state by some leaders.

The strong sense of togetherness and shared concerns has made both settlements successful in dealing with legal issues and state efforts for resettlements. For example, the dwellers learned to refuse resettlement allocation papers from the FCDA, as accepting the papers will be tantamount to accepting their displacement. This rejection of resettlement packages is considered a resistance strategy because without agreement by both parties, the state planning authorities cannot forcefully demolish the settlements as they had done in the past. According to many of the stakeholders interviewed, informal settlement dwellers have mastered the act of instituting court cases to obtain court injunctions on state institutions to halt development control exercises within their settlements or the demolition of individual buildings. While there are still several other active court cases between the dwellers and the state planning institutions (especially FCDA and Development Control), and some of them have not ended in favour of the dwellers, the locals believe that these litigations have prevented the displacement of most dwellers. A tribal head in Mpape remarked that “the government can do anything anytime…if not for the court, they would have demolished all our houses.” The litigations have significantly enhanced the logjam around informal settlements, and the dwellers seem to have found solace in the judiciary against state planning authorities and other contending actors.

Joining mainstream politics and alliances with state actors has helped the dwellers in their efforts to make their own places resilient to replacement. These practices are also pivotal to the success of other resistance strategies, as the state is the central actor capable of validating or refuting the dwellers’ claims and contentions. Some dwellers hold political appointments in state agencies. For example, a political leader in Mabushi claimed that they have allies within the state planning agencies who feed them with information on the various plans against the dwellers allowing them to strategize before the plans are executed. In what can be described as clientelism, the Mpape people boasted a large population size that could determine the outcomes of municipal elections. In one of the focus groups, one resident said: “…during (municipal) elections, even if a candidate wins other polling units, if the Mpape result is not out yet, you cannot be confident of winning, because the Mpape population can win you any election, they do not joke with us.”

The joining of mainstream politics and alliances with state actors has led to some advancements in the built environment and infrastructure of settlements. A political leader in Mabushi said: “it was much later after some of us enter politics, that we were able to do more for the community, for example, during my tenure (as the Speaker of Abuja Municipal Area Council) I was able to influence the addition of more classrooms to the government school and more transformers to the community, but we as a community are the initiators of all the developmental projects….” Dwellers’ engagement in politics has also facilitated their penetration into state institutions to make allies with state actors to garner support for their agitation. This set of state actors includes relatives and family members, dwellers working in state institutions, people who are sympathetic to their struggles, and some state actors with vested interest in informal settlements. All these efforts of the dwellers and the leaders have resulted in shaping new meanings and identities of Mabushi and Mpape as resilient places with a strong sense of togetherness and joint concerns related to displacement.

Conclusion

Place-making — the efforts of people to craft the use, functions, and meanings of place — is a fruitful perspective to capture the efforts of informal settlement dwellers to organise, arrange, and give meaning to their everyday places in response to persistent threats of displacement. It provides an important framework for seeing informal settlement dwellers as agents who engage in place-making activities to adjust the meanings of place and belonging to their often-unfavorable social realities in informal settlements. Through place-making activities, informal settlement dwellers are able to strengthen tenure security, their right to stay, and their right to the city (Lefebvre, 1968). This paper shows how the dwellers in Mpape and Mabushi in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja, exhibit agency in securing their existence and resisting displacement in light of the regular threats of displacement. By shaping the materiality of the built environment as well as the meanings of place for the dwellers and the outsiders, residents in Mpape and Mabushi are able to mobilize and safeguard their communities’ continued existence in the urban space.

In the context of land insecurity, this place-making approach shows how the agency of informal settlement dwellers in making their homes and everyday places is deeply constrained not only by unfavourable legal and economic land tenure circumstances, but also by their perceived tenure security — their subjective group perceptions of security or protection from arbitrary displacement. The ways dwellers build their homes or the ways they relate to each other and make communities, the political actions they take, or even the trees they plant and the ways they go about daily routines like receiving post, are guided by their shared subjective understanding of what can protect them from arbitrary displacement. Their everyday choices about where they live are deeply limited by their sense of perceived tenure security and fear of losing their home. While the place-making approach is a fruitful perspective on resistance that sheds light to the agency of the dwellers, at the same time, it demonstrates how precarious lives are in an informal settlement and how the deprivation of the basic right to land security forces dwellers to place-making actions not guided by their free will or conviction, but by their basic need to exist, to keep their land, their dwellings, and to protect themselves from arbitrary displacement.

The findings of this study demonstrate the need for more research that captures the differences between legal and perceived tenure security and the ways in which they affect the everyday lives of people in informal settlements. They ways dwellers understand their tenure security differently from the imposed statutory rights from the state guides their everyday lives to a large extent. These differences need to be captured by researchers from different perspectives, and it is in an attempt to capture these differences that avenues for future research emerge. Place-making offers a crucial perspective; yet, research on the ways perceived tenure security affects the ways people make communities, relate to each other, and make important life choices such as education, job, personal relationships, as well as the ways in which they perceive and use natural resources, such as soil or water, can provide fruitful new understandings of the ways tenure insecurities affect people and places across different contexts.

References

Adu-Ampong, E. A., & Adams, E. A. (2019). But you are also Ghanaian, you should know”: Negotiating the insider–outsider research positionality in the fieldwork encounter. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(6), 583–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419846532

Alfaro d’Alençon, P., Smith, H., Álvarez de Andrés, E., Cabrera, C., Fokdal, J., Lombard, M., & Spire, A. (2018). Interrogating informality: Conceptualisations, practices and policies in the light of the New Urban Agenda. Habitat International, 75, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.04.007

Altman, I., & Low, S. M. (Eds.). (1992). Place attachment. Plenum.

Andres, L., Bakare, H., Bryson, J. R., Khaemba, W., Melgaço, L., & Mwaniki, G. R. (2021). Planning, temporary urbanism and citizen-led alternative-substitute place-making in the Global South. Regional Studies, 55, 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1665645

Arnot, C. D., Luckert, M. K., & Boxall, P. C. (2011). What is tenure security? Conceptual implications for empirical analysis. Land Economics, 87(2), 15. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.87.2.297

Berry, S. (2009). Property, authority and citizenship: Land claims, politics and the dynamics of social division in West Africa. Development and Change, 40(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01504.x

Chimhowu, A. (2019). The ‘new’ African customary land tenure. Characteristic, features and policy implications of a new paradigm. Land Use Policy, 81, 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.04.014

Courpasson, D., & Vallas, S. (2016). The Sage handbook of resistance. SAGE.

Courpasson, D., Dany, F., & Delbridge, R. (2017). Politics of place: The meaningfulness of resisting places. Human Relations, 70, 237–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716641748

Cresswell, T. (2004). Place: A short introduction. Blackwell Publishing.

Fabiyi, O. (2017). Urban space administration in Nigeria: Looking into tomorrow from yesterday. Urban Forum, 28, 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-016-9299-3

FAO (2002). Land tenure and rural development. United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation Land Tenure Studies no3. ISBN: 92–5–104846–0

Federal Government of Nigeria (1976). Federal Capital Territory ACT. (6). Lagos: Federal Government of Nigeria

Hall, R., Edelman, M., Borras, S. M., Scoones, I., White, B., & Wolford, W. (2015). Resistance, acquiescence or incorporation? An introduction to land grabbing and political reactions ‘from below.’ The Journal of Peasant Studies, 42(3–4), 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2015.1036746

Hornby, D., Royston, L., Kingwill, R., & Cousins, B. (2017). Tenure practices, concepts and theories in South Africa. In D. Hornby (Ed.), Securing land tenure in urban and rural South Africa (p. 26). Natal Press.

Lefebvre, H. (1968). Le Droit à la ville [The right to the city] (2nd ed.). Anthropos.

Lewicka, M. (2011a). On the varieties of people’s relationships with places: Hummon’s typology revisited. Environment and Behavior, 43(5), 676–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510364917

Lewicka, M. (2011b). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31, 207–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

Lombard, M. (2014). Constructing ordinary places: Place-making in urban informal settlements in Mexico. Progress in Planning, 94, 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2013.05.003

Malik, S., Roosli, R., Tariq, F., & Salman, M. (2019). Land tenure security and resident’s stability in squatter settlements of Lahore. The Academic Research Community publication, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.21625/archive.v3i2.508

Manzo, L. C. (2005). For better or worse: Exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 25, 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.01.002

Manzo, L. C., & Devine-Wright, P. (Eds.). (2014). Place attachment: Advances in theory, methods, and applications. Routledge.

Massey, D. (1991). A global sense of place. Marxism Today, 38, 24–29.

Massey, D. (2005). For Space (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Michelutti, E., & Smith, H. C. (2014). The realpolitik of informal city governance. The interplay of powers in Mumbai’s un-recognized settlements. Habitat International, 44, 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.07.010

Njoh, A. J. (2013). Equity, fairness and justice implications of land tenure formalization in Cameroon. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(2), 750–768. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01168.x

Nuhu, S. (2018). Peri-urban land governance in developing countries: Understanding the role, interaction and power relation among actors in Tanzania. Urban Forum, 30(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-018-9339-2

Onwujekwe, O., Orjiakor, C. T., Odii, A., et al. (2022). Examining the roles of stakeholders and evidence in policymaking for inclusive urban development in Nigeria: Findings from a policy analysis. Urban Forum, 33, 505–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-021-09453-5

Otubu, A. (2018). The land use act and land administration in 21st century Nigeria: Need for reforms. Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy, 9(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.4314/jsdlp.v9i1.5

Patel, K. (2013). The value of secure tenure: Ethnographic accounts of how tenure security is understood and realised by residents of low-income settlements in Durban. South Africa. Urban Forum, 24, 19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-012-9169-6

Quintana Vigiola, G. (2022). Understanding place in place-based planning: From space- to people-centred approaches. Land, 11(11), 2000. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11112000

Reale, A., & Handmer, J. (2011). Land tenure, disasters and vulnerability. Disasters, 35(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01198.x

Reerink, G., & van Gelder, J.-L. (2010). Land titling, perceived tenure security, and housing consolidation in the kampongs of Bandung. Indonesia. Habitat International, 34(1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.07.002

Roy, A. (2005). Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360508976689

Rubin, M. (2018). At the borderlands of informal practices of the state: Negotiability, porosity and exceptionality. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(12), 2227–2242. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1460466

Sjaastad, E., & Bromley, D. W. (1997). Indigenous land rights in Sub-Saharan Africa: Appropriation, security and investment demand. World Development, 25(4), 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(96)00120-9

Stacey, P. (2018). Urban development and emerging relations of informal property and land-based authority in Accra. Africa, 88(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972017000572

UN-Habitat (2008). Secure land rights for all. Global Land Tool Network (GLTN); Nairobi, Kenya, 2008. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10535/6047

United Nations. (2018). The world’s cities in 2018: Data booklet. Department of Economic and Social Afairs, Population Division

van der Haar, G., van Leeuwen, M., & de Vries, L. (2020). Claim-making as social practice — Land, politics and conflict in Africa. Geoforum, 109, 111–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.12.002

van Gelder, J. L., & Luciano, E. C. (2015). Tenure security as a predictor of housing investment in low-income settlements: Testing a tripartite model. Environment and Planning a: Economy and Space, 47(2), 485–500. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130151p

Wacquant, L. (2015). Revisiting territories of relegation: Class, ethnicity and state in the making of advanced marginality. Urban Studies, 53(6), 1077–1088. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015613259

Wacquant, L. (2008). Urban outcasts: A comparative sociology of advanced marginality. UK: Cambridge: Polity

Watson, V. (2009). The planned city sweeps the poor away …”: Urban planning and 21st century urbanization. Progress in Planning, 72, 151–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2009.06.002

Funding

Nuhu Adeiza Ismail received the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFUND) Overseas Scholarship Award granted to him in 2018 for his PhD study from the Federal Government of Nigeria. The primary research underlying this study was made possible through this award. Emmanuel Akwasi Adu-Ampong also received financial support from the Dutch Research Council (NWO) Veni Grant with number VI.Veni.201S.037 which made possible his contribution to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and initial analysis were performed by Ismail Adeiza Nuhu and subsequently further developed by Ana Aceska and Emmanuel Akwasi Adu-Ampong. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ana Aceska and Emmanuel Akwasi Adu-Ampong. All authors commented on all iterative draft versions of the manuscript until the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ismail, N.A., Aceska, A. & Adu-Ampong, E.A. “We Closed Down Mpape on the Judgement Day”: Resistance and Place-Making in Urban Informal Settlements in Abuja, Nigeria. Urban Forum 35, 179–195 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-023-09492-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-023-09492-0