Abstract

We study how changes in return migration patterns over the last decade impacted self-employment rates in Mexico. Using state historical migration rates as instruments, we calculate elasticities of self-employment to return migration of 0.093, 0.156, and 0.236 for all workers, males, and low-educated male workers, respectively. Back-of-the-envelope calculations indicate that the 0.18 percentage point decline in the return migration rates observed between 2006 and 2016 reduced the self-employment rate by 5.8 percent relative to the level seen in 2006. Additionally, we estimate the gains from migration and self-employment among Mexican return migrants controlling for observable and unobservable characteristics. While return migrants have earnings 1.72 log points higher than non-migrant Mexican workers, we do not find differences in the earnings of self-employed and wage-employed return migrants once we control for unobservable skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this paper, migrants are individuals who moved from Mexico (home country) to the United States (host country). Return migrants are individuals who migrated to the United States, stayed in that country for some time mainly to work or look for a job, and later decided to return to Mexico to settle there permanently.

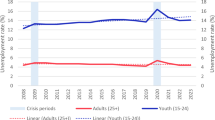

Authors’ calculations using Mexican census data and the 2005 and 2015 ENOE. We report the average yearly self-employment growth rate in urban areas among individuals in the labor force aged 15–65.

On a different strand of literature, studies that explicitly focused on the effect and uses of remittances have obtained mixed results. Yang (2008) analyzes the effect of remittances on Filipino households. He finds that an increase in remittances leads to enhanced human capital accumulation and entrepreneurship. Members of remittance-receiving households work more hours on self-employment and become more likely to start more capital-intensive household enterprises after a negative economic shock. Murillo-Castaño (1984) highlights how in the case of Colombian return migrants from Venezuela, savings were used to buy, establish, or expand self-employment activities, but only after the basic needs of the household members have been satisfied. On the contrary, studies using data from Albania have endorsed the view that savings from migration are spent primarily in conspicuous consumption and non-productive investment such as housing (Carletto et al. 2004; King and Vullnetari 2003). Finally, studies analyzing the uses of remittances in small communities in Mexico have found that remittances tend to be disproportionately used for consumption and have no impact on investment decisions (Dinerman 1982; López 1986).

That period includes the years during which return migration occurred. To study the effect of return migration between 2002 and 2006, we use data from the ENOE in 2007 and include employed individuals who joined a wage job or became self-employed between 2003 and 2007. We repeat these calculations using all the years in the sample. To analyze the effect of return migration between 2012 and 2016, we use data from the ENOE from 2017 and include employed individuals who joined a wage job or became self-employed between 2013 and 2017.

The survey conducted in Mexican airports is available since 2009. Individuals returning by plane represent six percent of the total number of return migrants.

Our specification does not include controls for occupation and state economic conditions. The occupational choice might be endogenously determined by migration experience, and the effect of migration on self-employment might be mediated by occupation or industry choice. Similarly, state economic conditions can be endogenous.

State-level migration rates from the 1920s are provided by Christopher Woodruff at http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/staff/academic/woodruff/data/mexico_migration.

To account for the effect of the economic conditions in the United States on the return migration rates, we use weighted US unemployment and state GDP growth rates. We construct weights using origin and destination states to account for the geographical distribution of Mexican migrants in the United States. The US weighted unemployment rate associated with a Mexican state is constructed using the proportion of migrants from that state who migrate to different destinations in the United States, multiplied by the unemployment rate in those destinations. A similar methodology was used to estimate the US weighted GDP growth rates. We include these variables as instruments in our main specification and test for instrument redundancy. We could not reject the null that the additional instruments are redundant. For that reason, we did not include them in our final regressions.

We divide Mexico into four regions according to their geographical and migratory characteristics. Northern Mexico: Baja California Norte, Baja California Sur, Sonora, Sinaloa, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas. Western Mexico: Aguascalientes, Colima, Durango, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán, Nayarit, San Luis Potosi, and Zacatecas. Central Mexico: Morelos, Queretaro, Tlaxcala, Puebla, Hidalgo, D.F., Estado de Mexico, and Veracruz. Southern Mexico: Campeche, Chiapas, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, and Yucatan.

According to Guevara Ramos (2008), the percent distribution of Mexican migrants to the United States by region was 47.8 percent from Western Mexico, 23.4 percent from Southern Mexico, 18.3 percent from Central Mexico, and 10.5 percent from Northern Mexico between 2003 and 2006.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines a long-term migrant as a person who moves to another country for at least 12 months. But given the characteristics of the Mexican migration, we had to use an alternative definition. The EMIF asks respondents the number of years since the first and last entry. To identify temporary and permanent migrants, we use the number of years from the first entry. Therefore, our measure of duration does not imply continuous presence in the United States.

.

We estimate the percentage change in self-employment by dividing each regression coefficient by the average self-employment rate of the corresponding group of workers. The percentage change in the return migration rate is one divided by the average return migration rate of the period (0.265). For all workers (Column 1), the percentage change in self-employment is (0.053/0.150 = 0.353); the percentage change in the return migration rate is (1/0.265 = 3.777), and the elasticity is (0.353/3.777 = 0.093).

This evidence is consistent with previous research that has documented higher migration rates from relatively poor communities in Mexico. In those regions, individuals tend to have lower endowments and more liquidity constraints, which could decrease their probability of starting a business and become self-employed. Moreover, the critical role that networks at destination have on the migration decision could have also contributed to this negative correlation. Individuals are more likely to migrate if members of their family or community have previous migration experience. Households in that region will be more likely to receive remittances from abroad. High dependence on remittances could decrease the incentives of individuals to work, start their own business, and become self-employed.

We multiply the 0.18 percentage point decrease in the return migration rate of Mexican workers by the coefficient estimated (0.053) and divide by the self-employment rate observed in 2016 (0.165).

We use ten years as a cutoff point to define temporary and permanent migrants and show how the results would change if we move that threshold. For that reason, we have an overlap between 8 and 10 years. We show results if we consider them as temporary or permanent migrants. To verify that using workers with less than five, eight, and ten years in the United States is a reliable indicator of temporary migration, we use self-reported country of residence. More than 79 percent of those who returned within the first five years, more than 78 percent of those who returned within the first eight years, and 77 percent of those who returned within the first ten years reported Mexico as their country of residence. Conversely, more than 65 percent of those who report more than eight years from the first entry, 70 percent of those who report more than ten years from the first entry, and 73 percent of those who report more than twelve years from the first entrance indicate the United States is their country of residence.

“Oportunidades” is the most important anti-poverty program of the Mexican Government.

While we can make inferences regarding the type of selectivity of the return migrants relative to the non-immigrant population, we cannot analyze the selectivity of migration since we only observe migrants who return.

The propensity score is the conditional probability of assignment to a particular treatment given a vector of observed characteristics.

We report the average of the estimates using matching to the nearest neighbor and to the two nearest neighbors.

See Table 3.

Similar results were obtained when matching the nearest neighbor.

References

Blanchflower D, Oswald A (1998) What makes an entrepreneur? J Law Econ 16(1):26–60

Bohn S, Lofstrom M, Raphael S (2014) The effects of state-level legislation targeted towards limiting the employment of undocumented immigrants on the internal composition of state populations: The case of Arizona. Rev Econ Stat 96(2):258–269

Borjas G, Bratsberg B (1996) Who leaves? The outmigration of the foreign-born. Rev Econ Stat 78(1):165–176

Borraz F (2005) Assessing the impact of remittances on schooling: The Mexican experience. Glob Econ J 5(1):1–30

Briggs V (2004) Guestworker Programs: Lessons from the Past and Warnings for the Future. Center for Immigration Studies, Washington

Carletto C, Davis B, Stampini M, Trento S, Zezza A (2004) Internal Mobility and International Migration in Albania. FAO ESA Working Paper No. 04–13

Chiquiar D, Salcedo A (2013) Mexican Migration to the United States: Underlying Economic Factors and Possible Scenarios for Future Growth. Migration Policy Institute, Washington

Dinerman IR (1982) Migrants and Stay-at-Homes: A Comparative study of rural Migration from Michoacan, Mexico. Monograph Series No. 5. Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, San Diego

Dustmann C, Kirchkamp O (2002) The optimal migration duration and economic activities after re-migration. J Dev Econ 67:351–372

Gitter S, Gitter R, Southgate D (2008) The impact of return migration to Mexico. Estudios Econ 23(1):3–23

Goldsmith-Pinkham P, Sorkin I, Swift H (2020) Bartik instruments: What, when, why, and how. Am Econ Rev 110(8):2586–2624

Gonzalez-Barrera A (2015) More Mexicans Leaving Than Coming to the U.S. Pew Hispanic Center, Washington

Guevara Ramos E (2008) Pobreza, Migracion, Remesas y Desarrollo Economico. B - EUMED, Spain

Hanson G, Woodruff C (2003) Emigration and Educational Attainment in Mexico. University of California at San Diego, Mimeo

Hoekstra M, Orozco-Aleman S (2017) Illegal immigration, state law, and deterrence. Am Econ J Econ Pol 9:228–252

Ilahi N (1999) Return migration and occupational change. Rev Dev Econ 3(2):170–186

Jaeger DA, Ruist J, Stuhler J (2018) Shift-share instruments and the impact of immigration. (No. w24285). National Bureau of Economic Research

King R, Vullnetari J (2003) Migration and Development in Albania. Development Research Centre on Migration, Globalization, and Poverty, Sussex Centre for Migration Research, Working Paper C5

Lacuesta A (2010) A revision of the self-selection of migrants using returning migrant’s earnings. Ann Econ Stat 97(98):235–259

López G (1986) La Casa Dividida: Un Estudio de Caso Sobre Migración a Estados Unidos en un Pueblo Michoacano. El Colegio de Michoacán, Zamora

McCormick B, Wahba J (2001) Overseas Work Experience, Savings and Entrepreneurship amongst Return Migrants to LDCs. Scott J Political Econ 48(2):164–178

McKenzie DJ, Hildebrandt N (2005) The Effects of Migration on Child Health in Mexico. United States: World Bank, Development Research Group, Trade Team

McKenzie D, Rapoport H (2007) Network effects and the dynamics of migration and inequality: theory and evidence from Mexico. J Dev Econ 84(1):1–24

McKenzie D, Rapoport H (2010) Self-selection patterns in Mexico-U.S. migration: The role of migration networks. Rev Econ Stat 92(4):811–821

McKenzie D, Rapoport H (2011) Can Migration reduce educational attainment? Evidence from Mexico. J Popul Econ 24(4):1331–1358

Mesnard A (2004) Temporary migration and capital market imperfections. Oxf Econ Pap 56(2):242–262

Murillo-Castaño G (1984) Effects of emigration and return on sending countries: The case of Colombia. Int Soc Sci J 36(3):453–467

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2016) Self-employment rate (indicator). https://doi.org/10.1787/fb58715e-en. https://data.oecd.org/emp/self-employment-rate.htm. Accessed 1 Jun 2021

Orrenius P, Zavodny M (2009a) The effects of tougher enforcement on the job prospects of recent latin American immigrants. J Policy Anal Manage 28(2):239–257

Orrenius P, Zavodny M (2009b) Tied to the Business Cycle: How Immigrants Fare in Good and Bad Economic Times. Migration Policy Institute, Washington

Passel J, Cohn D, Gonzalez-Barrera A (2012) Net Migration from Mexico Falls to Zero—and Perhaps Less. Pew Hispanic Center, Washington

Piracha M, Vadean F (2010) Return migration and occupational choice: Evidence from Albania. World Dev 38(8):1141–1155

Reinhold S, Thom K (2013) Migration experience and earnings in the Mexican labor market. J Hum Resour 48(3):768–820

Robertson R, Halliday T, Vasireddy S (2020) Labour market adjustment to third-party competition: Evidence from Mexico. World Econ 43(7):1977–2006

Wahba J (2015) Selection, selection, selection: The impact of return migration. J Popul Econ 28:535–563

Wahba J, Zenou Y (2009) Out of sight, out of mind: Migration, entrepreneurship and social capital. Reg Sci Urban Econ 42(5):890–903

Woodruff C, Zenteno R (2007) Migration networks and microenterprises in Mexico. J Dev Econ 82(2):509–528

Yang D (2008) International migration, remittances and household investment: Evidence from Philippine Migrants’ Exchange Rate Shocks. Econ J 118(528):591–630

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Orozco-Aleman, S., Gonzalez-Lozano, H. Return Migration and Self-Employment: Evidence from Mexican Migrants. J Labor Res 42, 148–183 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-021-09319-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-021-09319-6