Abstract

People differ in their predispositions to value safety maintenance (i.e., disease prevention regulatory focus) or pleasure pursuit (i.e., pleasure promotion regulatory focus). Extending recent research, results of a cross-sectional study with participants living in Portugal and Spain (N = 770) showed that these individual differences resulted in a trade-off between potential health risks and pleasure rewards in sexual practices and experiences with casual partners. Specifically, people who were more focused on promotion (vs. prevention) reported riskier and more unrestricted sexual activities (more frequent condomless sex activities; more casual partners) and experienced more positive sexual outcomes (more sexual satisfaction; more positive and less negative affect related to condomless sex). This pattern of results remained the same after controlling for country differences, suggesting the robustness of our findings across different cultural contexts. Our study shows the complexity of sexual decisions and align with our reasoning that prevention-focused people tend to prioritize health safety, whereas promotion-focused people tend to prioritize sexual pleasure. Theoretical and applied implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Studies in Portugal and Spain have been documenting negative temporal trends in the perceived severity of certain sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and condom use intentions (Giménez-García et al., 2022), inconsistent condom use rates (e.g., Castro, 2016; Costa et al., 2018; Santos et al., 2018), low frequency of STI testing (e.g., Mendes et al., 2014; Rodrigues, de Visser, et al., 2023; Teva et al., 2018), and increased prevalence of STI diagnoses in recent years (e.g., Geretti et al., 2022; Sentís et al., 2021; Vives et al., 2020). To better understand changes in sexual behaviors and sexual health practices, researchers have argued the importance of considering individual differences and psychological variables (Hatfield et al., 2010; Laan et al., 2021; Sales & Irwin, 2013). For example, studies have consistently shown that despite the risks, many people engage in sexually risky behaviors (e.g., not wearing a condom during intercourse; Ballester-Arnal et al., 2022; Copen et al., 2022; Harper et al., 2018; Katz et al., 2023). However, these findings may be rendered meaningless if researchers fail to consider that people have sex for multiple reasons (Dawson et al., 2008; Gravel et al., 2016; Meston & Buss, 2007), vary in their willingness to pursue short-term and long-term partners (Gangestad & Simpson, 2000; Schmitt, 2005), or adhere to gender norms and sexual scripts to a different extent (Sanchez et al., 2005; Weitbrecht & Whitton, 2020; Wiederman, 2005), among other individual and contextual variables that influence sexual behavior.

The Regulatory Focus Theory (Higgins, 2015) offers an empirically supported framework that helps understand people’s likelihood to pursue goals and navigate decision-making processes, based on their predominant motivational orientation toward either losses or gains. Briefly, people who are more focused on prevention are motivated by safety and strive to avoid losses, whereas people who are more focused on promotion are motivated by advancement and strive to obtain gains. These motives shape how people perceive their environment and make decisions across different domains, including health-related and sex-related decisions (Woltin & Yzerbyt, 2015; Zou & Scholer, 2016). Using samples from different countries-Portugal, Spain, Germany, and the United States-, research has extended this framework to sexual health and wellbeing outcomes. Overall, differences in a person’s predisposition towards health and safety maintenance (i.e., adopting a prevention focus) or sexual pleasure pursuit (i.e., adopting a promotion focus) uniquely shape various sexual practices. More specifically, people who are more focused on prevention are also more aware of sexual health threats (Rodrigues et al., 2019), have more positive condom use attitudes (Rodrigues & Lopes, 2023), feel like they have more control over condom use (Rodrigues et al., 2022), and are less likely to make exceptions about not using condoms (Rodrigues, 2023). In contrast, people who are more focused on promotion report stronger intentions to have condomless sex even during health-threatening contexts (i.e. COVID-19 pandemic; Rodrigues, 2022), use condoms less consistently with casual partners (Rodrigues et al., 2020), and are more sexually satisfied (Evans-Paulson et al., 2022). And yet, being more focused on promotion does not equate to lacking sexual health concerns. Indeed, people who are more focused on promotion get tested for STIs more often and for a larger number of STIs, and go to routine sexual health check-ups more frequently (Rodrigues, de Visser, et al., 2023).

These differences in sexual health practices are aligned with people’s representations of condoms. Indeed, Rodrigues, Carvalho, and colleagues (2023) asked people to indicate what they considered to be the main functions of condoms, as well as situations and conditions under which people were more likely to use condoms or forgo condom use with casual partners (i.e., reasons for [not] using a condom). Results showed that people who were more focused on prevention endorsed health protection as one of the main functions of condoms, considered condom use to be facilitated when people have safety concerns (particularly when people are responsible and cautious with their health), have greater behavioral control (particularly when people plan the sexual encounter or have control over the situation), and enact preparatory behaviors (e.g., had condoms available beforehand). In contrast, condomless sex was considered more likely when people lack proper sex education (particularly when people fail to prioritize sexual protection or lack the knowledge of potential health consequences). People who were more focused on promotion, however, mainly construed condoms as barriers to sexual pleasure, and considered condom use to be facilitated by risk awareness (particularly when people are in high-risk situations and one-night stands), certain sexual activities (particularly when people want to pursue sexual pleasure and seek novel sexual experiences), and concerns with hygiene and health. In contrast, condomless sex was considered more likely when people are in the heat of the moment or have unexpected encounters, have negative STI testing results, want to pursue physical sensations (particularly sexual pleasure and excitement), and want to increase intimacy with their partner. Taken together, these studies indicate that sexual motives have a crucial role in the way people perceive the consequences and benefits of their sexual behaviors.

Current Study and Hypotheses

Past research has examined prevention and promotion scores separately (e.g., Rodrigues & Lopes, 2023), computed a continuous index (e.g., Evans-Paulson et al., 2022; Rodrigues et al., 2019), or categorized participants according to their predominant focus (e.g., Rodrigues, 2023). We took a different approach and sought to identify for the first time whether different latent profiles emerged based on the responses to our main predictor measure (i.e., regulatory focus in sexuality). This analytic strategy allows to establish profiles based on data patterns and categorize people with a certain degree of probability (Bauer, 2022; Spurk et al., 2020), instead of relying on a priori groups. The profiles identified in this analysis were then compared to determine differences in retrospective practices and experiences. Our main goal was to determine if different profiles were associated with trade-offs between potential risks for health safety and rewards for sexual pleasure in sexual practices and experiences with casual sexual partners. Drawing on past research, we expected participants with a predominant promotion profile (vs. prevention profile) to indicate having had condomless sex more frequently (H1) and with a larger number of partners (H2), feeling more sexually satisfied with their casual partners (H3), and experiencing more positive and less negative affect related to their condomless sex activities (H4). As the type of sexual activity can influence decision-making patterns (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2022; Habel et al., 2018; Ssewanyana et al., 2015; Stone et al., 2006), the examination of sexual behaviors delved into the contrasts between penetrative acts (vaginal and/or anal sex) and oral sex. Lastly, we explored differences between Portugal and Spain, and examined whether our main results were consistent after controlling for any a priori differences. The current study was part of the Prevent2Protect project (https://osf.io/rhg7f), and our hypotheses were pre-registered (https://osf.io/caqnt).

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 770) were adults between the ages of 18 and 62 (M = 31.32, SD = 9.12) living in Spain (56.1%) and Portugal (43.9%). Most participants identified as White (77.9%), around half identified as women (56.4%), and most identified as heterosexual (78.3%). Around half of the participants lived in metropolitan areas (62.2%), had a university degree (43.8%), were currently working (57.4%), and were able to manage their expenses with their current income (45.2%). Demographic characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Comparisons based on country of residence revealed some differences. Participants in Spain were older (M = 31.90, SD = 9.55) than participants in Portugal (M = 30.57, SD = 8.50), t(768) = 2.20, p = .044, d = 0.15. As shown in Table 1, there were also differences in ethnic background, p = .002, sexual orientation, p = .009, completed education, p < .001, occupation, p < .001, and socioeconomic status, p = .012. Specifically, we had a higher proportion of participants in Portugal (vs. Spain) who identified as Black (vs. White), who identified as heterosexual (vs. bisexual), had a high school degree (vs. university or post-graduate degrees), were stay-at-home parents or unemployed (vs. students), and were finding it very difficult to live comfortably (vs. living very comfortably) with their current income.

Measures

Apart from the regulatory focus in sexuality measure, none of the measures used in this study have been reported in our prior research. All measures were subject to Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) with maximum likelihood estimation using JASP (Version 0.18.01). We examined model fit based on standard recommendations (Byrne, 2012), including indices of absolute fit (χ2; SRMR), relative fit (TLI), and non-centrality (CFI; RMSEA). We also examined the reliability indexes using McDonald’s omega (Hayes & Coutts, 2020).

Regulatory Focus in Sexuality

We used the measure developed by Rodrigues and colleagues (2019) to assess the extent to which participants are typically driven by promotion motives in sex (six items; e.g., “I am typically striving to fulfill my desires with my sex life”) or prevention motives in sex (three reverse-scored items; e.g., “Not being careful enough with my sex life has gotten me into trouble at times”). Responses were given on 7-point rating scales (1 = Not at all true of me to 7 = Very true of me). CFA results showed good fit indices for a 2-factor model, χ2 (25) = 79.59, p < .001, SRMR = .03, TLI = 0.96, CFI = .97, and RMSEA = .05. Responses were mean averaged on each subscale, with higher scores indicating a greater focus on prevention (ω = .73) and promotion in sexuality (ω = .79).

Condomless Sex Frequency

We assessed retrospective sexual behaviors by asking participants to think about their past sexual activity with casual partners and indicate if they ever had vaginal sex (1 = No; 2 = Yes), anal sex (1 = No; 2 = Yes), oral sex (1 = No; 2 = Yes). Participants who had vaginal sex (95.1%), anal sex (60.3%), and/or oral sex (95.2%) were then asked to indicate how often they typically have sex without using a condom (1 = Never to 7 = Every time I have sex) and with how many casual partners they had sex without using a condom (open-ended response). Questions were presented for vaginal, anal, and oral sex separately.

Sexual Satisfaction

We used the short version of the New Sexual Satisfaction Scale (Štulhofer et al., 2010) and asked participants to think about their casual sex encounters and rate how sexually satisfied they are with themselves (six items; e.g., “The quality of my orgasms”) and with their casual partners (six items; e.g., “The variety of my sexual activities”). Responses were given on 7-point rating scales (1 = Not at all satisfied to 7 = Extremely satisfied). CFA results showed good fit indices to a 2-factor model, χ2 (50) = 242.52, p < .001, SRMR = .03, TLI = .95, CFI = .96, and RMSEA = .07. Responses were mean averaged on each subscale, with higher scores indicating more sexual satisfaction with oneself (ω = .87) and with others (ω = .81).

Affective Reactions Related Condomless Sex

We used a modified version of the International Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) Short Form (Thompson, 2007) to assess positive and negative emotions after having condomless sex with casual partners. The original measure assesses the extent to which people typically experience positive (10 items; e.g., excited) and negative affective states (10 items; e.g., guilty). In this study, participants were asked to indicate how much they felt each emotion the last time they had condomless sex with a casual partner, using a 7-point rating scale (1 = Not at all to 7 = Extremely). The scale was presented twice, once for condomless penetrative (vaginal or anal) sex and once for condomless oral sex. These questions were automatically skipped for participants who used condoms every time they had casual sex. Initial CFA results for both versions showed that, unlike the original scale, item 5 (i.e., “alert”) was negatively correlated with the positive affect factor and therefore had to be reverse-coded. Final CFA results showed good fit indices for a 2-factor model for the condomless penetrative version, χ2 (30) = 220.04, p < .001, SRMR = 0.08, TLI = 0.93, CFI = 0.95, and RMSEA = 0.09, and for the condomless oral sex version, χ2 (30) = 268.86, p < .001, SRMR = 0.10, TLI = 0.92, CFI = 0.95, and RMSEA = 0.11. Responses were mean averaged, with higher scores indicating more positive (ω = .80) and negative affect (ω = .86) related to condomless penetrative sex, and more positive (ω = .85) and negative affect (ω = .86) related to condomless oral sex.

Procedure

Prospective participants were recruited from the Clickworker data collection platform and invited to take part in an online survey about sexuality and sexual practices. Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years old, residing in Portugal or Spain, having engaged in any type of sexual activity in the past (i.e., oral sex or intercourse), and being currently single without a romantic partner. Upon reading their rights (e.g., confidentiality; possibility to abandon the study at any point), participants were asked to give their informed consent in order to proceed with the study. Participants were then asked inclusion criteria questions to assess their eligibility for the study. Those who failed to meet these criteria were automatically redirected to the end of the survey and thanked for their interest. Those who met the criteria were first asked demographic questions, followed by our main variables. Upon survey completion, participants received 5€ in their user account as compensation for participation. The survey could be presented either in Portuguese or Spanish. More details about the procedure are reported elsewhere (Rodrigues, Carvalho, et al., 2023; Rodrigues, de Visser, et al., 2023). A copy of the survey in each language, and the respective list of measures in English, are available (https://osf.io/re9q4).

Analytic Plan

We started by computing descriptive statistics and overall correlations between our continuous measures. Then, instead of categorizing participants based on their overall scores on the regulatory focus in sexuality measure, we computed latent profile analyses (LPA). This person-centered approach accounts for individual differences and allows us to identify groups of participants who share similar response patterns on our predictor variable (Bauer, 2022). Specifically, we explored latent models with up to four profiles (i.e., the combination of low/high values in each subscale). Based on standard recommendations (Ferguson et al., 2020; Spurk et al., 2020), we used Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), sample size–adjusted BIC (SABIC), and the p values of both the Lo, Mendell, and Rubin test (LMR), and the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT). Lower values on AIC, BIC, and SABIC indicate a better fit to the data, and significant LMR and BLRT results suggest that the model with an additional latent profile has a better fit than the previous one. We also considered entropy (values ≥ 0.80 indicate lower classification uncertainty) and the probability of cases for each profile (profiles with < 5% of the sample were discarded). After selecting the best model, we compared scores on the regulatory focus in sexuality subscales between profiles using t-tests to validate the categorization. After this, we computed five Linear Mixed Models using JASP to examine profile differences in (a) condomless sex frequency (vaginal sex vs. anal sex vs. oral sex), (b) number of condomless sex casual partners (vaginal sex vs. anal sex vs. oral sex), (c) sexual satisfaction (with oneself vs. casual partners), (d) affective reactions related to condomless penetrative sex (positive affect vs. negative affect), and (e) affective reactions related to condomless oral sex (positive affect vs. negative affect). This statistical approach allows us to account for response interdependency by considering repeated units of analysis (e.g., negative and positive affective reactions) nested within participants (West et al., 2022). In all analyses, the full model included the profiles identified in the LPA, the different levels of a given outcome variable, and the respective interactions as fixed effects, as well as by-participant random intercepts. When interactions were found, we computed contrasts with Holm adjustment to compare profiles. Lastly, we explored if the results changed when we added the country of residence as an additional factor in the models. Anonymized data and outputs are available (https://osf.io/euvfb).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations between outcome variables are presented in Table 2. Overall, participants who had condomless sex more frequently reported having done so with a larger number of casual partners, reported more sexual satisfaction, and reported more positive and less negative affect related to condomless sexual activities. Participants who were more sexually satisfied reported more positive affect related to condomless sex activities, whereas participants who were less sexually satisfied reported more negative affect related to condomless sex activities.

Latent Profile Analyses

Results summarized in Table 3 show that models with two and three latent profiles had the best fit, considering that only 4% of the participants were assigned to one profile in the final model. We retained the model with two latent profiles, given a larger reduction of AIC, BIC, and SABIC indicators and higher entropy values. Comparisons between profiles showed higher scores on the prevention subscale among participants categorized in Profile 1 (n = 270; M = 5.43, SD = 1.56) when compared to Profile 2 (n = 500; M = 4.71, SD = 1.56), t(768) = 6.21, p < .001, d = 0.47. In contrast, higher scores on the promotion subscale were observed among participants categorized in Profile 2 (M = 5.67, SD = 0.66) compared to Profile 1 (M = 3.71, SD = 0.80), t(768) = 36.48, p < .001, d = 2.76.

Differences According to Latent Profiles

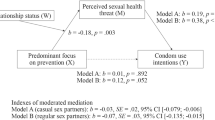

As shown in Table 4, participants categorized as more focused on promotion differed in most outcome variables when compared to participants categorized as more focused on prevention. The results are depicted in Fig. 1.

Condomless Sex Frequency

We found a main effect of latent profiles, such that promotion-focused (vs. prevention-focused) participants reported more frequent condomless sex activities. We also found a main effect of the type of sex, indicating that participants reported less frequent condomless anal (vs. vaginal) sex, p < .001, and more frequent condomless oral (vs. vaginal) sex, p < .001. Lastly, the interaction between factors was also significant, F(2, 1283.33) = 3.11, p = .045. Specifically, promotion-focused (vs. prevention-focused) participants reported more frequent condomless vaginal, p = .029, and oral sex, p < .001.

Number of Condomless Sex Casual Partners

Results showed a main effect of latent profiles, indicating that promotion-focused (vs. prevention-focused) participants had condomless sex with a larger number of casual partners. There was also a main effect of type of sex, such that participants reported a smaller number of casual partners in condomless anal (vs. vaginal) sex, p = .004, and a larger number of casual partners in condomless oral (vs. vaginal) sex, p < .001. The interaction between factors was non-significant, F(2, 1222.93) = 1.60, p = .202.

Sexual Satisfaction

We found a main effect of latent profiles, indicating that promotion-focused (vs. prevention-focused) participants reported higher sexual satisfaction overall. There was also a main effect of the type of sexual satisfaction, such that participants reported being more sexually satisfied with themselves than with their casual partners. No significant interaction between factors emerged, F(1, 764.60) = 1.01, p = .316.

Affect Related to Condomless Sex

No significant main effects of latent profiles emerged. Instead, we found main effects for the type of affect, with participants reporting more positive (vs. negative) affect related to condomless penetrative and oral sex. We also found significant interactions between factors for condomless penetrative, F(1, 1045) = 19.29, p < .001, and oral sex, F(1, 1288) = 14.95, p < .001. Specifically, both types of condomless sex elicited more positive affect among promotion-focused (vs. prevention-focused) participants, both p < .001, whereas only condomless penetrative sex elicited more negative affect among prevention-focused (vs. promotion-focused) participants, p = .029.

Differences According to Country of Residence

We tested if our results changed when the country was included as an additional factor in the linear mixed models. Results showed that the participant’s country of residence interacted with the type of condomless sexual activity, p = .004, the type of sexual satisfaction, p = .027, and the type of affective reactions related to condomless penetrative sex, p = .049. Specifically, participants in Portugal reported less frequent condomless anal (vs. vaginal) sex, p < .001, and more frequent condomless oral (vs. vaginal) sex, p < .001, whereas participants in Spain reported only more frequent condomless oral (vs. vaginal) sex, p < .001 (no differences between condomless anal and vaginal sex emerged, p = .492). Participants in both countries reported more sexual satisfaction with themselves (vs. with their casual partners), both p < .001, with larger differences emerging among participants living in Spain. Lastly, participants in both countries reported more positive (vs. negative) affect related to condomless penetrative sex, both p < .001, with larger differences emerging among participants living in Portugal. Despite these differences, the results reported in our main analyses were overall the same.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study was framed by the Regulatory Focus Theory (Higgins, 2015) and built upon its recent extension to sexuality (e.g., Rodrigues, de Visser, et al., 2023; Rodrigues et al., 2020, 2022). Specifically, we examined the extent to which motivations for sexual health safety (i.e., focus on prevention in sexuality) and sexual pleasure (i.e., focus on promotion in sexuality) contributed to distinct sexual behaviors and experiences with casual partners among people residing in Portugal and Spain.

Aligned with past research, our results supported the existence of two main motivational profiles of regulatory focus in sexuality. When comparing both profiles, results generally supported our hypotheses. We found that participants who were more focused on promotion perceived more sexual pleasure rewards in their casual sex activities, and reported more unrestricted sexual activities and more positive sexual experiences. In contrast, participants who were more focused on prevention perceived more sexual health risks, and reported more restricted sexual behaviors and more negative sexual experiences. Specifically, participants who were predominantly focused on promotion (vs. prevention) reported having condomless sex more often (H1) and with a larger number of casual partners (H2; particularly in vaginal and oral sex), more sexual satisfaction with themselves and with their partners (H3), and more positive (and less negative) affect when thinking about their condomless sex experiences (H4). This pattern of results remained the same after controlling for country of residence, converging with findings from other cultural contexts (see also Evans-Paulson et al., 2022; Rodrigues, 2022, 2023). The results of our study extend past research by showing that safety and pleasure motives have distinct implications for the sexual practices and the sexual experiences people have with their casual partners. Overall, our findings show the importance of examining multiple sources of information to better understand sexual decision-making processes. For example, we extended past research (e.g., Ballester-Arnal et al., 2022) and showed that people have riskier sex when enacting certain types of sexual activity (i.e., oral vs. penetrative sex) and even feel more positive (and less negative) after doing so (e.g., more positive affect related to condomless oral sex than condomless penetrative sex). Our results also highlight the complexity of sexual decisions and align with our reasoning that regulatory focus in sexuality results in a trade-off, such that prevention-focused people tend to prioritize health safety over sexual pleasure, whereas pleasure-focused people tend to prioritize sexual pleasure over health safety.

We must also highlight some additional findings. Being more focused on prevention elicited more condom use, but this was less evident for oral sex when compared to vaginal or anal sex. Past research has provided initial evidence that prevention-focused people have weaker condom use intentions in certain situations (e.g., when there is a lower risk their partner has an STI; Rodrigues, 2022, 2023). We extended this evidence by showing that sexual activities perceived as potentially having fewer consequences for sexual health (e.g., oral sex; Halpern-Felsher et al., 2005) can also lead prevention-focused people to make more lenient decisions and render them at risk of negative sexual health outcomes (even without the benefits typically observed for sexual satisfaction, as our results suggest).

Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Even though our main argument was grounded on the premise that people’s predominant regulatory focus (i.e., trait variable) shapes different outcomes, including sex-related perceptions and behaviors, we are unable to establish causality given the cross-sectional nature of our data. Research has shown that momentary changes in regulatory focus can also be induced (Higgins, 2015), which raises the question if people momentarily change their regulatory focus in response to external cues related to sexual behaviors and sexual health (e.g., being diagnosed with an STI). Future studies could seek to implement longitudinal studies to test if and how sexual motivations are stable or instead change over time (e.g., as a response to life events, shifts in personal values and priorities, or contextual changes) and temporally determine sexual behaviors, perceived risks, and experiences with casual partners (e.g. condom use negotiation). Such design would also allow researchers to determine if the potential effects of regulatory focus in sexuality are independent of, or interact with, other individual differences (e.g., personality traits; age) and past experiences (e.g., unplanned pregnancies), relational dynamics (e.g., trusting the partner), and social pressures (e.g., gender scripts). Such a comprehensive analysis would allow researchers to better understand the relative weight of individual motivations (i.e., prevention or promotion focus) for sexual decisions and experiences, how people trade-off between health safety and sexual pleasure, and which conditions are likely to limit (or enhance) sexual risk perceptions.

Generalizations should also be taken with caution given that individual differences and behaviors (e.g., regulatory focus in sexuality; condom use) may depend on cultural norms and pressures, or contextual variables (e.g., sexual scripts; communication culture; sexuality education). Our results with people residing in two European countries converge with past studies conducted in Germany and the United States. And yet, our sample of participants was relatively young and WEIRD (i.e., Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic; Henrich et al., 2010), which might restrict the overall generalizability of our findings. Hence, future studies could seek to collect data with a more diverse sample of participants (e.g., people from different socioeconomic and cultural contexts) to test the extent to which our current findings are extended to other social and cultural contexts.

Extensions and Implications

Our results could be extended in several ways. For example, the Dual Control Model of Sexual Response (Bancroft et al., 2009; Janssen & Bancroft, 2023) postulates that people are more likely to activate inhibited (vs. aroused) sexual responses when faced with sexual stimuli perceived as threatening (vs. pleasurable). The Sexual Communal Strength framework (Muise & Impett, 2016) postulates that being motivated to respond to the partner’s sexual needs has benefits for sexual desire and satisfaction (Shoikhedbrod et al., 2023). Building upon these theoretical premises, future studies could seek to explore potential underlying psychological mechanisms of the associations between regulatory focus in sexuality and sexual behaviors and experiences. For example, being more focused on prevention may be linked to less pleasurable sexual activities with casual partners because people have more inhibited sexual responses (see also Evans-Paulson et al., 2022). In contrast, being more focused on promotion may be linked to more pleasurable sexual activities (both individual and dyadic, as our findings suggest) because people have more aroused sexual responses and communal motives in sex. Such empirical evidence would be valuable for professionals (e.g., sex therapists, sexual health clinics, etc.) to better understand the needs and struggles of people depending on their predominant regulatory focus.

Our findings also have the potential to extend existing programs to improve sexuality education. For example, intervention programs designed to improve knowledge about STIs and behavioral skills in Portugal and Spain have been shown to improve safer sex attitudes, risk perceptions, and behavioral intentions (e.g., Espada et al., 2015; Morales et al., 2016; Reis et al., 2011). However, these programs (much like the sexuality education curricula usually offered at schools in both countries; Picken, 2020) tend to have hygienist and biological approaches, mostly centering around the potential risks of sexual behavior (e.g., STI acquisition, unplanned pregnancy) and less often on its benefits (e.g., knowledge of one’s body, sexual pleasure). Indeed, a recent study has shown that people who considered that sexuality education received during school years influenced their current thoughts and behaviors in sex are also more likely to protect their health (e.g., more focused on prevention; more likely to enact sexual communication; more likely to use condoms), but have less positive feelings about sex (Rodrigues et al., 2024). Our findings converge with the need to have a more comprehensive approach to sexual health and wellbeing (Ford et al., 2019), particularly considering that including pleasure in sexual and reproductive health programs can help improve condom use frequency (Zaneva et al., 2022). Informed by our findings, sexuality education curricula in schools and awareness campaigns should strive to educate people on how to protect their sexual health (particularly relevant for people who are more focused on promotion) without forgoing their sexual wellbeing (particularly relevant for people who are more focused on prevention), and work to change the narrative that both aspects of sexuality are mutually exclusive.

Data availability

Materials, anonymized data, and outputs that support our findings herein reported are available upon request from the first author and publicly shared on the Prevent2Protect Open Science Framework page (https://osf.io/rhg7f).

References

Ballester-Arnal, R., Giménez-García, C., Ruiz-Palomino, E., Castro-Calvo, J., & Gil-Llario, M. D. (2022). A trend analysis of condom use in Spanish young people over the two past decades, 1999–2020. AIDS and Behavior, 26(7), 2299–2313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03573-6

Bancroft, J., Graham, C. A., Janssen, E., & Sanders, S. A. (2009). The dual control model: Current status and future directions. The Journal of Sex Research, 46(2–3), 121–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490902747222

Bauer, J. (2022). A primer to latent profile and latent class analysis. In M. Goller, E. Kyndt, S. Paloniemi, & C. Damşa (Eds.), Methods for researching professional learning and development: Challenges, applications and empirical illustrations (pp. 243–268). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08518-5_11

Castro, Á. (2016). Sexual behavior and sexual risks among Spanish university students: A descriptive study of gender and sexual orientation. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(1), 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0210-0

Copen, C. E., Dittus, P. J., Leichliter, J. S., Kumar, S., & Aral, S. O. (2022). Diverging trends in US male-female condom use by STI risk factors: A nationally representative study. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 98(1), 50–52. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2020-054642

Costa, E. C. V., McIntyre, T., & Ferreira, D. (2018). Safe-sex knowledge, self-assessed HIV risk, and sexual behaviour of young Portuguese women. Portuguese Journal of Public Health, 36(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1159/000486466

Dawson, L. H., Shih, M.-C., de Moor, C., & Shrier, L. (2008). Reasons why adolescents and young adults have sex: Associations with psychological characteristics and sexual behavior. The Journal of Sex Research, 45(3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490801987457

Espada, J. P., Morales, A., Orgilés, M., Jemmott, J. B., & Jemmott, L. S. (2015). Short-term evaluation of a skill-development sexual education program for Spanish adolescents compared with a well-established program. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.018

Evans-Paulson, R., Widman, L., Javidi, H., & Lipsey, N. (2022). Is regulatory focus related to condom use, STI/HIV testing, and sexual satisfaction? The Journal of Sex Research, 59(4), 504–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1961671

Ferguson, S. L., Moore, G. E. W., & Hull, D. M. (2020). Finding latent groups in observed data: A primer on latent profile analysis in Mplus for applied researchers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(5), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419881721

Ford, J. V., Corona Vargas, E., Finotelli, I., Jr., Fortenberry, J. D., Kismödi, E., Philpott, A., Rubio-Aurioles, E., & Coleman, E. (2019). Why pleasure matters: Its global relevance for sexual health, sexual rights and wellbeing. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(3), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2019.1654587

Gangestad, S., & Simpson, J. (2000). The evolution of human mating: Trade-offs and strategic pluralism. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 573–587. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0000337X

Geretti, A. M., Mardh, O., de Vries, H. J. C., Winter, A., McSorley, J., Seguy, N., Vuylsteke, B., & Gokengin, D. (2022). Sexual transmission of infections across Europe: Appraising the present, scoping the future. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 98(6), 451–457. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2022-055455

Giménez-García, C., Ballester-Arnal, R., Ruiz-Palomino, E., Nebot-García, J. E., & Gil-Llario, M. D. (2022). Trends in HIV sexual prevention: Attitudinal beliefs and behavioral intention in Spanish young people over the past two decades (1999–2020). Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 31, 100677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100677

Gravel, E. E., Pelletier, L. G., & Reissing, E. D. (2016). “Doing it” for the right reasons: Validation of a measurement of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation for sexual relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 92, 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.015

Habel, M. A., Leichliter, J. S., Dittus, P. J., Spicknall, I. H., & Aral, S. O. (2018). Heterosexual anal and oral sex in adolescents and adults in the United States, 2011–2015. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 45(12), 775–782. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000889

Halpern-Felsher, B. L., Cornell, J. L., Kropp, R. Y., & Tschann, J. M. (2005). Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: Perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Pediatrics, 115(4), 845–851. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-2108

Harper, C. R., Steiner, R. J., Lowry, R., Hufstetler, S., & Dittus, P. J. (2018). Variability in condom use trends by sexual risk behaviors: Findings from the 2003–2015 national youth risk behavior surveys. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 45(6), 400–405. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000763

Hatfield, E., Luckhurst, C., & Rapson, R. L. (2010). Sexual motives: Cultural, evolutionary, and social psychological perspectives. Sexuality & Culture, 14(3), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-010-9072-z

Hayes, A. F., & Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use Omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But…. Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Beyond WEIRD: Towards a broad-based behavioral science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X10000725

Janssen, E., & Bancroft, J. (2023). The dual control model of sexual response: A scoping review, 2009–2022. The Journal of Sex Research, Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2219247

Katz, D. A., Copen, C. E., Haderxhanaj, L. T., Hogben, M., Goodreau, S. M., Spicknall, I. H., & Hamilton, D. T. (2023). Changes in sexual behaviors with opposite-sex partners and sexually transmitted infection outcomes among females and males ages 15–44 years in the USA: National Survey of Family Growth, 2008–2019. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 52(2), 809–821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02485-3

Laan, E. T. M., Klein, V., Werner, M. A., van Lunsen, R. H. W., & Janssen, E. (2021). In pursuit of pleasure: A biopsychosocial perspective on sexual pleasure and gender. International Journal of Sexual Health, 33(4), 516–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2021.1965689

Mendes, N., Palma, F., & Serrano, F. (2014). Sexual and reproductive health of Portuguese adolescents. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 26(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2012-0109

Meston, C. M., & Buss, D. M. (2007). Why humans have sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(4), 477–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9175-2

Morales, A., Espada, J. P., & Orgilés, M. (2016). A 1-year follow-up evaluation of a sexual-health education program for Spanish adolescents compared with a well-established program. European Journal of Public Health, 26(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv074

Muise, A., & Impett, E. A. (2016). Applying theories of communal motivation to sexuality. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(8), 455–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12261

Picken, N. (2020). Sexuality education across the European Union: An overview. European Comission. https://doi.org/10.2767/869234

Reis, M., Ramiro, L., de Matos, M. G., & Diniz, J. A. (2011). The effects of sex education in promoting sexual and reproductive health in Portuguese university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 477–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.266

Rodrigues, D. L. (2022). Regulatory focus and perceived safety with casual partners: Implications for perceived risk and casual sex intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology & Sexuality, 13(5), 1303–1318. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.2018355

Rodrigues, D. L. (2023). Focusing on safety or pleasure determine condom use intentions differently depending on condom availability and STI risk. International Journal of Sexual Health, 35(3), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2023.2212651

Rodrigues, D. L., Carvalho, A. C., de Visser, R. O., Lopes, D., & Alvarez, M.-J. (2024). Do different sources of sexuality education contribute differently to sexual health and well-being outcomes? Examining sexuality education in Spain and Portugal. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075241249172

Rodrigues, D. L., Carvalho, A. C., Prada, M., Garrido, M. V., Balzarini, R. N., de Visser, R. O., & Lopes, D. (2023). Condom use beliefs differ according to regulatory focus: A mixed-methods study in Portugal and Spain. The Journal of Sex Research, Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2181305

Rodrigues, D. L., de Visser, R. O., Lopes, D., Prada, M., Garrido, M. V., & Balzarini, R. N. (2023). Prevent2Protect project: Regulatory focus differences in sexual health knowledge and behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 52(4), 1701–1713. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02536-3

Rodrigues, D. L., & Lopes, D. (2023). Seeking security or seeking pleasure in sexual behavior? Examining how individual motives shape condom use attitudes. Current Psychology, 42(21), 17649–17660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02926-1

Rodrigues, D. L., Lopes, D., & Carvalho, A. C. (2022). Regulatory focus and sexual health: Motives for security and pleasure in sexuality are associated with distinct protective behaviors. The Journal of Sex Research, 59(4), 484–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1926413

Rodrigues, D. L., Lopes, D., Pereira, M., Prada, M., & Garrido, M. V. (2019). Motivations for sexual behavior and intentions to use condoms: Development of the regulatory focus in sexuality scale. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(2), 557–575. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1316-2

Rodrigues, D. L., Lopes, D., Pereira, M., Prada, M., & Garrido, M. V. (2020). Predictors of condomless sex and sexual health behaviors in a sample of Portuguese single adults. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.10.005

Sales, J. M., & Irwin, C. E. (2013). A biopsychosocial perspective of adolescent health and disease. In W. T. O’Donohue, L. T. Benuto, & L. W. Tolle (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent health psychology (pp. 13–29). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6633-8_2

Sanchez, D. T., Crocker, J., & Boike, K. R. (2005). Doing gender in the bedroom: Investing in gender norms and the sexual experience. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(10), 1445–1455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205277333

Santos, M. J., Ferreira, E., Duarte, J., & Ferreira, M. (2018). Risk factors that influence sexual and reproductive health in Portuguese university students. International Nursing Review, 65(2), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12387

Schmitt, D. (2005). Sociosexuality from Argentina to Zimbabwe: A 48-nation study of sex, culture, and strategies of human mating. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 247–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X05000051

Sentís, A., Montoro-Fernandez, M., Lopez-Corbeto, E., Egea-Cortés, L., Nomah, D. K., Díaz, Y., de Olalla, P. G., Mercuriali, L., Borrell, N., Reyes-Urueña, J., & Casabona, J. (2021). STI epidemic re-emergence, socio-epidemiological clusters characterisation and HIV coinfection in Catalonia, Spain, during 2017–2019: A retrospective population-based cohort study. British Medical Journal Open, 11(12), e052817. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052817

Shoikhedbrod, A., Rosen, N. O., Corsini-Munt, S., Harasymchuk, C., Impett, E. A., & Muise, A. (2023). Being responsive and self-determined when it comes to sex: How and why sexual motivation is associated with satisfaction and desire in romantic relationships. The Journal of Sex Research, 60(8), 1113–1125. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2130132

Siegel, S., & Castellan Jr., N. J. (1988). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed). Mcgraw-Hill.

Spurk, D., Hirschi, A., Wang, M., Valero, D., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, 103445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103445

Ssewanyana, D., Sebena, R., Petkeviciene, J., Lukács, A., Miovsky, M., & Stock, C. (2015). Condom use in the context of romantic relationships: A study among university students from 12 universities in four central and eastern European countries. European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 20, 350–360. https://doi.org/10.3109/13625187.2014.1001024

Stone, N., Hatherall, B., Ingham, R., & McEachran, J. (2006). Oral sex and condom use among young people In the United Kingdom. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38(1), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1363/3800606

Štulhofer, A., Buško, V., & Brouillard, P. (2010). Development and bicultural validation of the new sexual satisfaction scale. The Journal of Sex Research, 47, 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490903100561

Teva, I., de Araújo, L. F., & de la Paz Bermúdez, M. (2018). Knowledge and concern about STIs/HIV and sociodemographic variables associated with getting tested for HIV among the general population in Spain. The Journal of Psychology, 152(5), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2018.1451815

Thompson, E. R. (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106297301

Tory Higgins, E. (2015). Regulatory focus theory. In R. A. Scott & S. M. Kosslyn (Eds.), Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences: An interdisciplinary, searchable, and linkable resource (pp. 1–18). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0279

Vives, N., Garcia de Olalla, P., González, V., Barrabeig, I., Clotet, L., Danés, M., Borrell, N., & Casabona, J. (2020). Recent trends in sexually transmitted infections among adolescents, Catalonia, Spain, 2012–2017. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 31(11), 1047–1054. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462420940911

Weitbrecht, E. M., & Whitton, S. W. (2020). College students’ motivations for “hooking up”: Similarities and differences in motives by gender and partner type. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 9(3), 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/cfp0000138

West, B. T., Welch, K. B., Gałecki, A. T., & Gillespie, B. W. (2022). Linear mixed models: An overview. In B. T. West, K. B. Welch, A. T. Gałecki, & B. W. Gillespie (Eds.), Linear mixed models: A practical guide using statistical software (pp. 9–58). Chapman and Hall/CRC. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003181064-2

Wiederman, M. W. (2005). The gendered nature of sexual scripts. The Family Journal, 13(4), 496–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480705278729

Woltin, K.-A., & Yzerbyt, V. (2015). Regulatory focus in predictions about others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41, 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214566188

Zaneva, M., Philpott, A., Singh, A., Larsson, G., & Gonsalves, L. (2022). What is the added value of incorporating pleasure in sexual health interventions? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 17(2), e0261034. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261034

Zou, X., & Scholer, A. A. (2016). Motivational affordance and risk-taking across decision domains. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215626706

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). This research was supported by grants awarded to DLR by the Social Observatory of the “la Caixa” Foundation (Ref.: CF/PR/SR20/52550001) and Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Ref.: 2020.00523.CEECIND).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was previously approved by the Ethics Council at Iscte-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (#70/2021) and was in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodrigues, D.L., Carvalho, A.C., Balzarini, R.N. et al. Safety and Pleasure Motives Determine Perceived Risks and Rewards in Casual Sex. Sexuality & Culture (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10243-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10243-x