Abstract

Expectations for behavior that might influence early-stage attraction in romantic relationships are likely to be influenced by cultural values, such as those found in cultures of honor. Honor-based ideals emphasize reputation maintenance and create powerful expectations for the behaviors of men and women. This study sought to examine the role of masculine honor norms in how college women in the southern United States respond to behavioral cues presented by a man in an online dating simulation. Specifically, women who more strongly endorsed masculine honor norms demonstrated an insensitivity to aggressive behavior reported by a man who was a potential romantic partner compared to women who did not endorse these same honor norms. Results indicate that honor-oriented women reported strong romantic interest in a male even when he reveals aggressive actions in his online dating profile. However, women who do not strongly endorse masculine honor norms reported significantly less romantic interest in the aggressive male compared to an otherwise-equivalent non-aggressive male. These results suggest that the impact of honor values on relational patterns can begin as early as the initial attraction stage before any interaction occurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There are many ways romantic partners connect with each other. From chance encounters in public spaces, to having a “blind date” set up by a trusted friend, men and women find ways of meeting prospective romantic partners and determining how interested they are in pursuing a relationship. Romantic attraction during initial encounters is driven by a variety of influences, one of which is socialized expectations conveyed through cultural norms. While some women find physical features paramount in initial attraction, others might look for less tangible qualities such as a sense of humor, honesty, and respect. Indeed, one need only consider the romantic relationships of their friends and family to recognize the variety of characteristics that individuals are looking for when seeking a partner. When identifying what makes a man attractive, women might be influenced by cultural values. These values can be quite different from one another across cultural types and between individuals within the same culture (Leung & Cohen, 2011), resulting in the possibility that what one woman finds attractive might be entirely unattractive to another woman. The present study sought to identify how the values dominant within honor-oriented cultures might influence the ways women view behavioral acts of aggression in response to insults within an online dating paradigm and how such views might enhance or undermine romantic interest in a potential dating partner.

Honor Cultures

The label “honor culture” characterizes societies that place a very high premium on the maintenance and defense of reputation, making reputation defense a “central organizing theme” of social life (Leung & Cohen, 2011). Examples of present-day honor cultures include the U.S. South and West, Central and South America, and countries throughout the Middle East and surrounding the Mediterranean (Brown, 2016; Chesler, 2010; Nisbett & Cohen, 1996; Peristiany, 1966; Rodriguez-Mosquera et al., 2000). Honor cultures typically prize reputations for strength, toughness, and intolerance of disrespect for men, whereas these cultures tend to prize reputations for familial loyalty and chastity for women (Barnes et al., 2014; Vandello & Cohen, 2003, 2008; Vandello et al., 2009). Because a person’s social value is dependent on his or her reputation in an honor culture (in contrast to a dignity culture, which imbues individuals with worth simply because they are human; Leung & Cohen 2011), the extent to which people live up to the standards demanded by honor determines their worth in society. Once a person’s reputation has been sufficiently tarnished, honor might prove impossible to regain. Thus, people in honor cultures tend to be extremely vigilant to honor threats and willing to go to extreme lengths to defend their honor (e.g., Cohen et al., 1996).

Examples of such honor-defensive behaviors have been described across a variety of domains by social-psychological research over the past several decades. For example, one of the earliest investigations of honor-related dynamics in social psychology involved a set of studies by Cohen and colleagues, who showed that male college students reacted much more aggressively to a realistic insult in a laboratory setting if they had grown up in the U.S. South than if they had grown up in the U.S. North (Cohen et al., 1996). Indeed, Cohen and colleagues even showed that southern men’s testosterone and cortisol levels spiked following an insult, which did not occur among northern men. Subsequent studies supported these early results across a variety of controlled situations in the lab (Bosson et al., 2009; Vandello et al., 2008a, 2008b; Vandello & Cohen, 2003), and research beyond the lab showed that these aggressive responses might be precursors to more extreme forms of violence in the real world, including argument-based homicides (Nisbett & Cohen, 1996), school shootings (Brown et al., 2009), and even suicides (Osterman & Brown, 2011).

Honor and Romantic Relationships

The interdependence of male and female reputational concerns, combined with the particular types of reputations that are idealized for men and women, can also facilitate aggression in romantic relationships. For example, Vandello and Cohen (2003) found that participants from Brazil (an honor culture) were significantly more likely to condone violence in response to an unfaithful woman in a hypothetical vignette compared to participants from North America. Indeed, Brazilian participants rated a man who reacted with violence as being more honorable than the man who did not. Likewise, after witnessing what seemed to be a live interaction between a romantic couple that included aggression in response to perceived infidelity, southern American Anglo and Latino/a participants rated her more favorably if she subsequently decided to stay with the abusive partner and even encouraged her to do so, whereas northern American Anglo participants encouraged her to leave him and rated her more favorably when she indicated an intention to leave (Vandello & Cohen, 2003; see also Vandello et al., 2008a, 2008b, 2009).

Vandello, Cohen, and their colleagues have proposed that honor cultures promote schemas and scripts for how romantic interactions should unfold, (Vandello & Cohen, 2003, 2008; Vandello et al., 2009), and these scripts can lead to cultural acceptance of relationship violence in certain circumstances. Specifically, in order to be a good woman, a woman should embody the characteristics of purity, chastity, and loyalty (Vandello & Cohen, 2003). A woman’s place within a culture of honor is to serve her family, and once she is married, she is to obey and honor her husband. A woman’s honor is closely tied to both her family’s overall reputation as well as her husband’s honor. A man’s honor is displayed via acts of courage, bravery, and retaliatory aggression (Vandello & Cohen, 2003). Importantly, aggression for its own sake is not condoned within an honor culture (Cohen, 1998), but in response to a threat (whether actual or perceived) aggression is often touted as the most appropriate answer (Cohen & Nisbett, 1994), including within close relationships.

Given that society teaches individuals what is acceptable and expected within relationships (Cohen et al., 1999; Haj-Yahia, 1998, 2002; Pence & Paymar, 1993), it is plausible that schemas about what characteristics are seen as desirable and undesirable in a potential romantic partner might be just as influenced by honor-related values as are beliefs about how couples should behave within an established relationship. For instance, if a “real man” is one who exerts dominance and displays aggression when his masculine honor is threatened, women in honor cultures might be encouraged to pursue such men as dating partners, or at least exhibit less reluctance to pursue a romantic relationship with a man who exhibits behaviors that suggest a propensity for honor-related aggression. Based on socialization about what it means to be honorable (Henry, 2009), honor-oriented women might be less sensitive to cues that a man tends to respond to insults with high levels of aggression, even if that same propensity means he might one day direct his aggression toward them (Witte & Mulla, 2012).

The Present Study

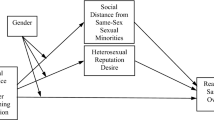

The purpose of the present study is to locate the influence of masculine honor on relational patterns at the earliest point in the cycle of a romantic relationship—specifically, the attraction and initiation stage (Connolly et al., 2013; Eastwick et al., 2011). We examine the extent to which women who vary in their endorsement of masculine honor-related beliefs and values find a potential romantic partner attractive and express willingness to initiate a relationship with him in the context of an online dating platform. By randomly assigning some women to discover his propensity for honor-related aggression (and other women not to discover this propensity), we can determine the extent to which honor-oriented women exhibit a degree of insensitivity to aggressive behavioral cues. This hypothesized insensitivity would lead to an interaction between women’s degree of masculine honor endorsement and the aggression cues present in the male target’s dating profile, such that women low in honor endorsement would find an aggressive man less appealing as a romantic partner than would women high in honor endorsement. Furthermore, we can examine whether honor-oriented women exhibit either relative insensitivity or absolute insensitivity in their romantic interests—the former requiring only that honor endorsement be significantly associated with romantic interest in an aggressive target, but the latter requiring that aggressive cues have no measurable effect on the romantic interest levels of highly honor-oriented women.

This study also assesses whether endorsing honor ideology influences women to view an aggressive dating target as similar to themselves or to their ideal romantic partner, to view such a dating target as possessing a variety of masculine honor-related characteristics, or to view him as simply being high in masculinity. Theoretically, such differences could potentially explain any insensitivity displayed by honor-oriented women toward an aggressive man. For example, it is possible that a woman who has learned that a prospective dating partner responded aggressively when insulted might view him as being very masculine, as being similar to her ideal romantic partner, or as possessing qualities indicative of honor norms. This study sought to test whether such variables could explain any insensitivities that might be displayed by women evaluating an aggressive (vs. non-aggressive) male.

Method

This study was reviewed and approved by the IRB. Participants came to the lab individually and after providing consent, they viewed one of two online dating profiles, depending on their assigned condition, that differed with respect to the presence or absence of aggressive behaviors presented in them (see Appendices A and B). Participants then rated the man in the profile on a number of dimensions, including how attractive they found him and how likely they would be to initiate contact with him, before responding to a brief set of demographic questions and being debriefed.

Sample

Ninety-eight female college students at a large institution in the U.S. Southwest completed this study in partial fulfillment of a research requirement for their introductory psychology course. The vast majority of the sample (77.5%) identified as White, while the remaining participants identified as other ethnicities. The average age of the sample was 18.9 years old, with a range of 18–27. Three participants did not have valid scores on our measure of masculine honor endorsement, so the analyses reported below include data only from 95 women.

Procedure and Materials

Prior to coming to the lab and as part of an extensive battery of measures unrelated to this study, participants had completed the 16-item honor ideology for manhood scale, or HIM, an individual difference measure developed by Barnes and colleagues (Barnes et al., 2012a, 2012b) to assess how strongly participants endorse honor-related beliefs and values associated with masculinity. Respondents indicate on a 1–9 scale how much they agree or disagree with items such as, “A real man doesn’t let other people push him around,” and “A real man never backs down from a fight,” with higher scores indicating greater endorsement of masculine honor norms. The HIM exhibited strong internal reliability in the present study (α = 0.91), consistent with previous research (e.g., Barnes et al., 2012a, 2012b).

When participants arrived at the lab, they were told that they would be participating in an early-stage assessment of a new online platform for matching romantic partners. Participants then viewed one of two male dating profiles (see Appendices A and B). General information about the man in the profile included college major, personality characteristics, hobbies, and a favorite recent experience, as well as a candid photo. Both profiles contained the following “non-aggressive” cues, written ostensibly by the male target: admitting to underage drinking, describing himself as adventurous, assertive, and strong-willed and as having a passion for hunting and rock climbing. The majority of these cues theoretically align with culture of honor norms (e.g., dominance, risk-taking), although they could easily be construed in a neutral, non-aggressive way.

Participants saw identical information in the two profiles, with one exception. In response to a prompt, the target in the non-aggressive condition recounted a recent annoying situation in which he stood in a long line to pay his tuition bill, only to find that he needed to visit another department first. However, he did not have time to go to the other department prior to his next class. The description of the incident indicated that he went to class rather than stand in another long line. The target in the aggressive condition, in contrast, recounted a recent annoying situation in which he was insulted by his boss in front of several customers. In response, the target reacted aggressively, throwing down his apron and walking out on the job, keying his boss’s car as he left before speeding out of the parking lot.

After reading one of these two profiles, participants indicated their romantic interest in the target by indicating their overall feelings of attraction toward him, how likely they would be to ask him out on a date, how likely they would be to go on a date if he asked them out, how likely they would be to send him a message on the dating website, how likely they would be to email him, and how likely they would be to start a short-term relationship with him. These items were rated from 1 to 7, with 1 indicating low interest and 7 indicating high interest (see Appendix C for exact response scales). These 6 responses were combined to form the composite dependent variable of romantic interest in the dating target (α = 0.93). Participants also responded to a question probing how likely they would be to start a long-term relationship with the target, but this item reduced reliability when assessing psychometric properties, so it was not included in the composite variable.

Participants also rated the target on a variety of characteristics that are theoretically linked with masculine honor, such as being tough, adventurous, competitive, and dominant (see Appendix D for exact response scales). We reasoned that this composite scale of 12 items (α = 0.55) might mediate the link between masculine honor ideology and romantic interest, in that more honor-oriented women might perceive the aggressive target as fulfilling honorable characteristics more strongly than the non-aggressive target. In line with this reasoning, participants also rated the target on several indicators of perceived similarity. This composite variable was composed of 3 items (α = 0.77) indicating how much the participant had in common with the target, how close the target was to the participant’s ideal partner, and how similar the target was to the participant’s current or most recent partner. This variable was included as a possible mediator in that more honor-oriented women might perceive more similarity with the aggressive target compared to the non-aggressive target.

Participants also indicated their perceptions of the overall masculinity and positivity of each profile. These variables represent potential alternative, more general, mediators of the hypothesized interaction between condition and HIM scores. Finally, participants indicated the extent to which various elements of the target profile had influenced their ratings, including the target’s response to the “most recent annoyance” question. This was designed to probe the level of awareness at which any differences in perception of the targets is processed. Due to the design of the study, the only difference between profiles was the “most recent annoyance” (refer to Appendices A and B), so if participants indicated that this element of the profile did not heavily influence their ratings, this would suggest any differences in sensitivities to aggressive behaviors might operate outside of conscious awareness. Participants took no longer than 30 minutes to complete the study, after which they were thanked for their participation, debriefed, and dismissed.

Results

We conducted a regression analysis that included the composite romantic interest variable as the DV and the mean-centered HIM, condition (coded 0 for the non-aggressive condition and 1 for the aggressive condition), and the interaction between the HIM and condition. The results indicated that condition significantly predicted romantic interest in the target, β = − 0.52, t(93) = − 5.98, p < .001. This main effect indicated that women who viewed the non-aggressive target expressed more romantic interest in him than did women who viewed the aggressive target. The HIM was not a significant predictor of romantic interest in the target overall, β = − 0.06, t(93) = − 0.53, p = .72. As predicted, however, the interaction between condition and the HIM was statistically significant, β = 0.26, t(93) = 2.23, p = .02.

In order to understand the nature of this interaction, we plotted the dependent variable at +/− 1 standard deviation from the mean of the HIM for each condition (see Fig. 1). The simple slope of masculine honor endorsement and romantic interest in the non-aggressive condition was not significantly different from 0, β = –0.064, t(93) = − 0.53, p = .72. In contrast, the association between masculine honor endorsement and romantic interest in the aggressive condition was significant and positive, β = 0.33, t(93) = 2.51, p = .007. As Fig. 1 shows, women who were low in honor endorsement viewed the target in the aggressive condition as significantly less desirable than did women high in honor endorsement. Indeed, the target’s behavior in the aggressive condition (compared to the non-aggressive condition) had an impact on the target’s desirability even among women high in masculine honor endorsement, β = – 0.31, t(93) = − 2.54, p = .01, but this impact was substantially smaller than it was among women low in masculine honor endorsement, among whom the behavior present in the aggressive profile had a large impact, β = – 0.71, t(93) = − 5.82, p < .001.

Given the results of this analysis, we next wanted to assess whether participants were aware of the influence of the most recent annoyance (the only difference between profiles) on their evaluations. Overall, participants indicated this element of the profile had little influence on their ratings, indicated by a mean of 3.46 (SD = 2.42) on a 7-point scale. An independent samples t-test revealed that there was a significant difference between profiles, with participants indicating the annoyance influenced their evaluations significantly more in the aggressive condition (M = 4.02, SD = 2.73) than in the non-aggressive condition (M = 2.87, SD = 1.89), t(93) = − 2.38, p = .02. However, a regression analysis probing this awareness indicated that the HIM [β = 0.09, t(93) = 0.80, p = .42] did not significantly predict the self-reported influence of the annoyance variable, but condition did [β = 0.24, t(93) = 2.42, p = .02]. The interaction between the HIM and condition likewise did not emerge as a significant predictor [β = − 0.13, t(93) = − 1.32, p = .19]. This analysis indicates that participants in the aggressive condition indicated significantly more influence of the most recent annoyance on their profile evaluations, but that this perceived influence did not differ based on masculine honor endorsement.

In addition to the above potential mediator analyses, we also created a composite honor characteristics scale (α = 0.55) consisting of 12 items typically associated with masculine honor. It is possible that women higher in masculine honor endorsement might notice these characteristics in the target profile, especially in the aggressive condition, whereas women lower in masculine honor endorsement might not evaluate the target in the same way. In order to assess this possibility, we entered the mean-centered HIM scores, condition, and their interaction into a regression equation predicting this composite variable. None of these variables emerged as a significant predictor of this composite variable: the HIM did not emerge as a significant predictor, [β = 0.10, t(93) = 0.71, p = .48], nor did condition [β = 0.07, t(93) = 0.67, p = .51] or their interaction [β = 0.06, t(93) = 0.40, p = .69]. Thus, neither honor orientation nor condition significantly impacted perceptions of the target’s masculine honor-related characteristics. Given the low alpha of this scale, we also performed a factor analysis of these items that revealed three sub-clusters. However, none of the clusters had reliable alphas, nor did they relate to the HIM or the composite variable of romantic interest (all rs less than 0.30).

Next, we examined the possibility that women higher in masculine honor endorsement might perceive more commonality between themselves and the target, particularly the aggressive target. In order to assess this possibility, we performed a regression analysis that included the mean-centered HIM variable, condition, and their interaction predicting this composite dependent variable of perceived similarity. The HIM emerged as a significant predictor [β = 0.20, t(93) = 2.03, p = .046], as did condition [β = − 0.29, t(93) = − 3.03, p = .003], but the interaction was not significant, β = 0.17, t(93) = 1.74, p = .086. This analysis indicates that women high in masculine honor endorsement did indeed perceive more similarity between themselves and the dating targets, and that all participants perceived more in common with the non-aggressive target than the aggressive target. However, there was insufficient evidence that women higher in masculine honor endorsement felt that they had more in common with either target compared to women low in masculine honor endorsement.

We expected that masculine honor endorsement might moderate the association between profile and the perceived masculinity of the target. This analysis revealed a strong positive association between condition and masculinity ratings, β = 0.30, t(93) = 3.02, p = .003. However, neither the HIM [β = − 0.12, t(93) = − 1.16, p = .25] nor the condition \(\times\) HIM interaction [β = − 0.09, t(93) = − 0.86, p = .39] was significant. This analysis indicates that everyone perceived the target in the aggressive condition as more masculine than the target in the non-aggressive condition. Thus, perceptions of masculinity were incapable of mediating the condition \(\times\) HIM interaction on romantic interest.

Similarly, we found that regardless of HIM scores, participants perceived the aggressive target (M = 3.51) as being less positive overall than the non-aggressive target (M = 4.67), t(93) = 4.68, p < .001. Neither honor endorsement [β = 0.03, t(93) = 0.30, p = .77] nor the interaction between honor and condition [β = 0.02, t(93) = 0.23, p = .82] were significant predictors of positivity ratings, however. Thus, profile positivity was not capable of serving as a mediator of our romantic interest findings. Data are available here: https://osf.io/kuq3e/?view_only=44d2c966861b40568e7f4f3b01be08ed.

Discussion

The current study assesses how certain behavioral cues might alter a man’s romantic appeal as a function of a woman’s masculine honor endorsement. Based on previous work on the priorities that dominate honor cultures (e.g., Vandello & Cohen 2003, 2008), we hypothesized that an aggressive male target might be viewed differently by women high (vs. low) in masculine honor orientation, with the former evaluating him more desirably than the latter. Stemming from a culture that condones aggression under a variety of honor-related situations, as well as excessive risk-taking (Barnes et al., 2012) and displays of toughness (Barnes et al., 2012a, 2012b), more honor-oriented women might exhibit greater interest in a prospective romantic partner, compared to less honor-oriented women, when he conforms to the cultural expectations of how a “real man” is supposed to behave when his honor is threatened (such as when he is publicly insulted). Thus, a man who responds to an honor threat with aggression, as was the case with the aggressive male in this study, might be viewed much more negatively by less honor-oriented women, who might see his behavior as a signal of how dangerous he could be when pushed, even (or perhaps especially) to his close relationship partners.

Results of the present study were generally in line with these predictions. Women did perceive the two profiles differently, depending on how strongly they endorsed masculine honor norms. Specifically, all women, regardless of masculine honor endorsement, indicated a greater romantic interest in the male target in the non-aggressive profile. However, women low in masculine honor endorsement displayed significantly less interest in the aggressive male target than did women high in masculine honor endorsement. It is worth noting that the items comprising the romantic interest variable did not merely indicate women’s willingness to respond positively to the target if he were to pursue them for a relationship. Rather, these items indicated women’s willingness to initiate romantic contact with the target. These results indicate that what women perceive as desirable is indeed shaped by cultural norms.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

A limitation of the current study is that the between-subjects design did not include the ability for participants to choose between the two targets. This sort of choice would be more in line with real-world situations in which women are presented with various available romantic partners. Thus, we cannot be sure that, if given a choice between an aggressive romantic partner and a non-aggressive one, most masculine honor-endorsing women would choose the former. Still, the fact that women who strongly endorsed masculine honor norms in this study indicated more romantic interest in the less aggressive target than they did in the more aggressive target suggests that these women might select a partner with a weaker propensity for violence if given the option.

Another limitation of the present study is that we were unable to determine the precise mechanism for the relative insensitivity of honor-oriented women to the cues posed by the aggressive male target. We suspected that honor-oriented women might see this prospective partner as being more possessive of honor characteristics, more similar to themselves or their ideal partner, or simply more masculine or more positive, compared to women low in honor orientation. However, none of the potential mediators of our romantic interest variable were successful in explaining why more honor-oriented women found the aggressive male target more alluring than did less honor-oriented women. We should note that a different measure of honor characteristics might lead to different outcomes, especially one that exhibited greater reliability than the one we used in the present study. Understanding better the precise mechanism or mechanisms that drive the pattern of romantic interest that we observed in the current study seems a goal well worth pursuing in future research (HIM; Barnes et al., 2012a, 2012b).

The design of this study included two potential male dating targets that differed only in one section of their online profile. In creating the conditions, we strove to select information that would convey different responses to a provocation. We recognize that in creating the profiles, we presented different provocations (waiting in lines compared to being insulted at work) in the profiles as well as how the man responded. Thus, our data do not allow us to predict how women might have viewed a target who responded aggressively to waiting in long lines or who did not respond aggressively when insulted. However, we decided it would be difficult, if not impossible, to create an insult-based provocation condition that women (and perhaps especially those who strongly endorse masculine honor norms) would find to be culturally “neutral.” We also did not want to leave uncertain how the target responded to either situation, which would run the risk of participants inferring different responses by each target. Future studies might benefit from examining a wider range of interpersonal provocations as well as a variety of aggressive and non-aggressive responses, which would allow us to understand better how women view potential dating partners as a function of their adherence to honor norms.

This study was conducted in the Southern U.S. with a small, mostly White, heterosexual sample of college-age women. Based on prior work in honor-related violence patterns (Brown et al., 2018; Vandello et al., 2008a, 2008b), there is reason to suspect that results might be different if this study were conducted with more diverse samples or people from other regions of the country. Future research should likewise examine how responses of women might change as a function of their age and their experiences of relationship-based aggression. Similarly, the ways in which men feel the pressure of honor-oriented norms to behave in retaliatory ways when faced with honor threats and in the presence of potential romantic partners might also be worth investigating.

In real life, the extent to which a person fulfills the behavioral expectations of his or her culture determines, to a large extent, the social status of that person, which contributes substantially to that person’s perceived mate value (Henry, 2009; Zayas & Shoda, 2007; Zentner & Mitura, 2012). Men in an honor culture who signal that they not only endorse the dominant values of their culture, but also live out those values, might achieve greater social status. It is possible that the perception of the aggressive target’s likelihood of ultimately having greater social status is what drove honor-oriented women to view him as being more desirable than less honor-oriented women did, a subtle calculus that these women might not have even been conscious of performing. Future research should explore this and other non-conscious mediators of attraction in order to determine more precisely why honor-oriented women do not exhibit as much sensitivity to the risks posed by the more aggressive target compared to less honor-oriented women. In addition, a valuable avenue for future work would be to assess existing romantic relationships to determine whether these differences in perceptions of romantic interest are displayed when women actually enter romantic partnerships. After all, it is different to imagine hypothetically dating an aggressive man than actually to pursue and begin a romantic relationship with one. Although the stakes are higher in the latter instance, those greater stakes might either reduce or enhance the power of honor-based norms to shape the perceptions and choices of romantic partners toward one another.

Practice Implications

It is important to emphasize what we did not find in this study. Specifically, women who more strongly endorsed masculine honor norms did not show enhanced interest in the aggressive male target compared to the non-aggressive target, meaning that we found evidence for relative insensitivity but not absolute insensitivity. Thus, even highly honor-oriented women viewed the aggressive target as less desirable than the non-aggressive target, even though they did so to a lesser extent than did women who were low in masculine honor orientation. We interpret this finding as showing that even the powerful norms of an honor culture do not make women completely oblivious to the possible risks associated with a man who displays aggression following a perceived honor threat. That suggests to us that it might be possible to enhance this sensitivity through education and other forms of socialization to help women avoid becoming romantically involved with men who might at some point pose a danger to them (O’Farrell et al., 2004; Whitaker et al., 2013; Yllo 1983; Yllo & Straus, 1990; Zayas & Shoda, 2007; Zentner & Mitura, 2012).

It bears mentioning that among many theoretically possible mediators of the link between masculine honor endorsement and women’s perceptions of the dating target, we found no evidence for a conscious difference driving their levels of sensitivity. That is, women high in masculine honor endorsement did, indeed, rate the aggressive target differently than did women low in masculine honor endorsement. However, when asked about the very information that clearly affected their evaluations (because it was, by design, the only difference between the two profiles), participants did not indicate that this information strongly influenced their judgments. In addition, perceptions of commonality with the dating target, perceptions of him as displaying honor-related characteristics, perceptions of masculinity, and perceptions of the overall positivity of the profile did not differ as a function of honor status. These null effects strike us as being interesting and important, insofar as they suggest that the mechanism for the demonstrated insensitivity displayed by honor-oriented women does not appear to operate at a conscious level of awareness. That possibility would mean that effective interventions designed to enhance women’s sensitivity to these aggressive cues could prove particularly challenging to create.

Conclusion

The current study advances existing work that highlights some of the dangers of living in a culture of honor (e.g., Barnes et al., 2012a, 2012b; Cohen, 1998), particularly to women in romantic relationships (Brown et al., 2018; Cohen & Vandello, 2008). We showed that women respond differently to a target in a dating profile who reveals aggressive responses to honor threats, depending on women’s level of endorsement of masculine honor. In particular, women who strongly endorse masculine honor seem at risk for pursuing potentially aggressive romantic partners. These results shed light on the fact that socialization processes can influence not only how established relationships transpire, but also whom people find desirable as potential mates. These results expand on evidence presented by Brown et al. (2018) of the risks of intimate partner violence associated with the normative expectations prevalent in honor cultures. In the aim of identifying the various locations within the life of a romantic relationship that honor norms prevail, this study indicates that women might well miss early signals a man might display in response to a perceived honor threat that could indicate his likelihood of engaging in even more severe acts of honor-related aggression, including toward the people around him. This study represents a small but important step in advancing our understanding of how masculine honor norms can shape relationship patterns.

Data Availability

The data generated by this study are available via the Open Science Framework repository here, https://osf.io/kuq3e/?view_only=44d2c966861b40568e7f4f3b01be08ed.

Code Availability

The data were analyzed using SPSS.

References

Barnes, C. D., Brown, R. P., & Osterman, L. L. (2012a). Don’t tread on me: Masculine honor ideology in the U.S. and militant responses to terrorism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(8), 1018–1029.

Barnes, C. D., Brown, R. P., & Tamborski, M. (2012b). Living dangerously: Culture of honor, risk-taking, and the nonrandomness of “accidental” deaths. Social Psychology and Personality Science, 3, 100–107.

Barnes, C. D., Brown, R. P., Carvallo, M., Lenes, J., & Bosson, J. (2014). My country, my self: Honor, identity, and defensive responses to national threats. Self & Identity, 13, 638–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2014.892529.

Bosson, J. K., Vandello, J. A., Burnaford, R. M., Weaver, J. R., & Wasti, S. A. (2009). Precarious manhood and displays of physical aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 623–634.

Brown, R. P. (2016). Honor bound: How a cultural ideal has shaped the american psyche. Oxford University Press. http://lccn.doc.gov/2015033718.

Brown, R. P., Osterman, L. L., & Barnes, C. D. (2009). School violence and the culture of honor. Psychological Science, 20(11), 1400–1405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02456.x.

Brown, R. P., Baughman, K. R., & Carvallo, M. R. (2018). Culture, masculine honor, and violence toward women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44, 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217744195.

Chesler, P. (2010). Worldwide trends in honor killings. Middle East Quarterly, 17(2), 3–11.

Cohen, D. (1998). Culture, social organization, and patterns of violence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 408–419. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.408.

Cohen, D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1994). Self-protection and the culture of honor: Explaining southern violence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 551–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205012.

Cohen, D., Nisbett, R. E., Bowdle, B. F., & Schwarz, N. (1996). Insult, aggression, and the southern culture of honor: An “experimental ethnography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 945–960. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.5.945.

Cohen, D., Vandello, J. A., Puente, S., & Rantilla, A. K. (1999). When you call me that, smile!”: How norms for politeness, interaction styles, and aggression work together in southern culture. Social Psychology Quarterly, 62, 257–275. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695863.

Connolly, J., Nguyen, H. N. T., Pepler, D., Craig, W., & Jiang, D. (2013). Developmental trajectories of romantic associations and associations with problem behaviours during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1013–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.006.

Eastwick, P. W., Finkel, E. J., & Eagly, A. H. (2011). When and why do ideal partner preferences affect the process of initiating and maintaining romantic relationships? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(5), 1012–1032. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024062.

Haj-Yahia, M. M. (1998). A patriarchal perspective of beliefs about wife beating among palestinian men from the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Journal of Family Issues, 19(5), 595–621. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251398019005006.

Haj-Yahia, M. M. (2002). Attitudes of arab women toward different patterns of coping with wife abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17(7), 721–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260502017007002.

Henry, P. J. (2009). Low-status compensation: A theory for understanding the role of status in cultures of honor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 451–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015476.

Leung, A. K. Y., & Cohen, D. (2011). Within- and between-culture variation: Individual differences and the cultural logistics of honor, face, and dignity cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(3), 507–526. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022151.

Nisbett, R. E., & Cohen, D. (1996). Culture of honor: Psychology of violence in the South. Westview Press.

O’Farrell, T. J., Murphy, C. M., Stephen, S., Fals-Stewart, W., & Murphy, M. (2004). Partner violence before and after couples-based alcoholism treatment for male alcoholic patients: The role of treatment involvement and abstinence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(2), 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.202.

Osterman, L. L., & Brown, R. P. (2011). Culture of honor and violence against the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(12), 1611–1623. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211418529.

Pence, E., & Paymar, M. (1993). Domestic violence information manual. In The Duluth domestic abuse intervention project. Springer Publishing, Inc.

Peristiany, J. (1966). Honour and shame: The values of Mediterranean society. Weidenfeld & Nicholson.

Rodriguez-Mosquera, P. M., Manstead, A. S. R., & Fischer, A. H. (2000). The role of honor-related values in the elicitation, experience, and communication of pride, shame, and anger: Spain and the Netherlands compared. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 833–844. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167200269008.

Vandello, J. A., & Cohen, D. (2003). Male honor and female fidelity: Implicit cultural scripts that perpetuate domestic violence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 997–1010. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.997.

Vandello, J. A., & Cohen, D. (2008). Gender, culture, and men’s intimate partner violence. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 652–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00080.x.

Vandello, J. A., Bosson, J. K., Cohen, D., Burnaford, R. M., & Weaver, J. R. (2008a). Precarious manhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1325–1339.

Vandello, J. A., Cohen, D., & Ransom, S. (2008b). U.S. southern and northern differences in perceptions of norms about aggression: Mechanisms for the perpetuation of a culture of honor. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39, 162–177.

Vandello, J. A., Cohen, D., Grandon, R., & Franiuk, R. (2009). Stand by your man: Indirect prescriptions for honorable violence and feminine loyalty in Canada, Chile, and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40, 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022108326194.

Whitaker, D. J., Murphy, C. M., Eckhardt, C. I., Hodges, A. E., & Cowart, M. (2013). Effectiveness of primary prevention efforts for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 4, 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.4.2.175.

Witte, T. H., & Mulla, M. M. (2012). Social norms for intimate partner violence in situations involving victim infidelity. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(17), 3389–3404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512445381.

Yllo, K. (1983). Sexual equality and violence against wives in american states. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 14(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.14.1.67.

Yllo, K., & Straus, M. (1990). Patriarchy and violence against wives: The impact of structural and normative factors. In M. Straus, & R. Gelles (Eds.), Physical violence in american families. Transaction Publishers.

Zayas, V., & Shoda, Y. (2007). Predicting preferences for dating partners from past experiences of psychological abuse: Identifying the ‘psychological ingredients’ of situations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206293493.

Zentner, M., & Mitura, K. (2012). Stepping out of the caveman’s shadow: Nation’s gender gap predicts degree of sex differentiation in mate preferences. Psychological Science, 23(10), 1176–1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612441004.

Funding

This research was partially funded by a Graduate Research Fellowship awarded to the corresponding author from the University of Oklahoma.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was designed and conducted by KRB under supervision of RPB in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the dissertation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Oklahoma and determined to be “exempt” status.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Aggressive Profile

Appendix B

Non-aggressive Profile

Appendix C

Composite Romantic Interest Questions

Appendix D

Please rate the person you saw in the profile for the following characteristics (items with * reverse-scored):

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baughman, K.R., Brown, R.P. Romantic Attraction and Insensitivity to Aggressive Cues Among Honor-Oriented Women. Sexuality & Culture 27, 1794–1812 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10090-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-023-10090-2