Abstract

What explains the differences between legislators’ orientation toward parochialism? While much literature exists on the effect of electoral rules on legislators’ focus on parochial interests in democratic legislatures, less is known about party-nominated and indirectly elected legislators. Drawn on interviews and an original dataset of congressional opinions in China, this analysis identifies non-electoral sources of pork barrel politics. It finds evidence of some orientation toward parochialism among indirectly elected provincial legislators in China. In particular, provincial legislators who concurrently work in lower-level political positions are more inclined to favor constituency-centered interests over broader public interests than non-official legislators. After ruling out several important alternative mechanisms, I argue that extra-legislative incentives and resources to solve local policy problems are the likely mechanisms that connect legislators’ occupation attributes with their advocacy focus. These findings have implications for the role of legislator attributes and the function of non-popularly elected legislatures.

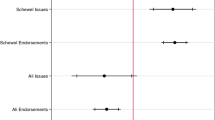

Source: author’s dataset

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Eleven percent of all dictatorships throughout 1946–2008 have unelected or appointed national legislatures (Svolik 2012, 36). In China, there are nearly 3000 national legislators, over 11,000 provincial legislators, and 118,000 prefectural legislators (Manion 2015, 32), all of whom are not elected through popular votes.

These theoretical frameworks highlight the role of authoritarian congresses in sustaining regime longevity, including co-opting (potential) opposition by making policy concessions (Gandhi and Przeworski 2007), by sharing rents (Truex 2014), and by mitigating commitment problems in power sharing (Magaloni 2008). Ruling elites in non-democracies also use the legislature to collect information on public demands (Manion 2015; O’Brien 1994) and quality of subordinates (Geddes 2006) and to provide information for the bureaucracy that could be incorporated into future policy (Hough and Fainsod 1979; Schuler 2020).

Legislators in China are almost entirely part time. In Vietnam, the number of full-time legislators has expanded to 30% since 2000 (Malesky and Schuler 2010, 489).

These positions include positions in the Chinese Communist Party departments, government bureaus, and congress committees.

Almost all Chinese legislators are part-time.

Interview AH21001, Interview GD19001, Interview GD20001, Interview YN21002.

See, for example, a 1988 regulation acquired during fieldwork, “Regulations of Shanghai Municipal Congress on Legislator Opinions” (shanghaishi renmin daibiao dahui guanyu daibiao jianyi piping he yijian de guiding). Based on the interview (Interview SH19001), if any delegate violates the regulation, congress staffs would send the opinion back to the delegate and ask her to rewrite and resubmit. Congress staffs would also inform the delegate of the regulation that prohibits submitting opinions directly related to the interests of delegates’ relatives, friends and workplaces. It is possible that officials’ opinions that aim to solve thorny policy-related problems are implicitly related to their workplace interests; however, because they are explicitly framed as advocating public interests for a specific geographic unit, they are considered as legitimate and acceptable.

The director of the personnel and deputy affairs congress committee commented: “we serve the legislators to help improve the quality of congressional opinions. If they, mostly non-official legislators, need any help (information) before raising opinions, we set up the platform (dajian pingtai), contact the government departments they want to visit, and organize investigation tours for them to gather information… These tours often span districts (i.e., prefectural-level units), we can contact different districts for legislators to have a more comprehensive understanding of the issue.” (Interview SH19001).

Military also constitutes an electoral unit. The local administrative levels in China include provincial, prefectural, county, and township levels.

According to Shi and Liu (2004, 275–298), out of the 82 electoral units (prefectural congresses) of Shanxi, Sichuan, and Zhejiang provincial congresses, the number of legislator candidates nominated by local party branches is equal to the number of seats in 80 electoral units; on average, over 90% of party nominees are elected to Guangdong, Shanxi, and Sichuan provincial congresses. Sun (2014) also finds that in indirect elections, almost every elected legislator is organization nominated.

Around 40–60% of Vietnam National Assembly legislators (1992–2007) work in government and party departments (Malesky and Schuler 2010, 487). Forty-four percent of the 11th Chinese National People’s Congress legislators are government/party employees (Truex 2016,110). See also, http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/0228/c1001-20623877.html, accessed in Nov. 2019. In Chinese provincial congresses, the proportion of official legislators varies from 27 to 49% (see Table 4 in Appendix).

Shanghai has the largest group of entrepreneur legislators (36%), especially SOE managers, while Anhui and Fujian provincial congresses have the largest number of private entrepreneur legislators (over 20%). Yet, entrepreneur legislators account for less than 10% in Yunnan.

http://www.spcsc.sh.cn/Attach/Attaches/201308/201308280315394754.pdf, accessed in July 2019.

These are based on articles 18 and 20 in the 2015 Law on Congress Legislators.

This is consistent with the finding that the level of localism is the lowest among provincial legislators in Shanghai. Only 17% of legislator opinions are local in Shanghai (see Table 2).

http://jyfw.bjrd.gov.cn/publicProposal/getProposalInfo.shtml?proposalId=188140, http://db.ynrd.gov.cn:9107/rdsuggestion/suggestiondetail.shtml?orgId=1&suggestionId=be36b82eaa344a418a9865b52dae1c5f, http://db.ynrd.gov.cn:9107/rdsuggestion/suggestiondetail.shtml?orgId=1&suggestionId=da6c97f53379413dba957ef48e77891a, http://jyfw.bjrd.gov.cn/publicProposal/getProposalInfo.shtml?proposalId=212114, accessed in Nov 2019.

Not all opinions have been put online and some sensitive ones were left unpublished. Interviewees in Shanghai and Anhui provinces mentioned that over 90% of opinions have been released on their congress websites (InterviewSH18001, InterviewAH19001). Tianjin congress, a provincial-level municipality congress, is dropped from the sample due to an exceptionally low number of available opinions (i.e., 194 opinions for the 16th Tianjin congress) compared to other provincial-level units and thus a concern for selection bias.

Public organizations include party and government departments, congress committees, public institutions such as hospitals and universities, and united frontline organizations including satellite parties, Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (zhengxie), and mass organizations(quntuan zuzhi).

Reply documents in D province were acquired during fieldwork in D province in 2019.

The case of Shanghai is somewhat unique in the way that it remains the only province (out of the sampled six provinces) outrightly prohibiting promoting work-place interests in legislators’ opinions. The innovation mentioned above in Shanghai is neither observed in other provinces. Therefore, the pattern uncovered in this article shall have some external validity and persistency.

See http://cpc.people.com.cn/18/n/2012/1109/c350825-19535943.html, accessed July 2020.

References

Ames, Barry. 2001. The deadlock of democracy in Brazil. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

André, Audrey, Sam Depauw, and Shane Martin. 2015. Electoral systems and legislators’ constituency effort: The mediating effect of electoral vulnerability. Comparative Political Studies 48 (4): 464–496.

Blaydes, Lisa. 2010. Elections and distributive politics in Mubarak’s Egypt. Cambridge University Press.

Carey, John. 1996. Term limits and legislative representation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Carey, John, and Matthew Shugart. 1995. Incentives to cultivate a personal vote: A rank ordering of electoral formulas. Electoral Studies 14 (4): 417–439.

Catalinac, Amy. 2016. From pork to policy: The rise of programmatic campaigning in japanese elections. The Journal of Politics 78 (1): 1–18.

Chen, Chuanmin. 2019. Getting their voices heard: Strategies of China’s provincial people’s congress deputies to influence policies. China Journal 82: 46–70.

Chen, Chuanmin. 2020. Local economic development and the performance of municipal people’s congress deputies in China: An explanation for regional variation. Journal of Chinese Political Science 25: 395–410.

Chen, Chuanmin, and Dongya Huang. 2020. Workplace-based connection: incentives for part-time deputies in China’s municipal people’s congresses. Working paper.

Cho, Young Nam. 2002. From ‘rubber stamps’ to ‘iron stamps’: The emergence of Chinese local people’s congresses as supervisory powerhouses. The China Quarterly 171: 724–740.

Crisp, Brian, Escobar-Lemmon. Maria, Jones Bradford, Jones Mark, and Taylor-Robinson. Michelle. 2004. Vote-seeking incentives and legislative representation in six presidential democracies. The Journal of Politics 66 (3): 823–846.

Curto-Grau, Marta, Alfonso Herranz-Loncan, and Albert Sole-Olle. 2012. The Spanish ‘Parliamentary Road’, 1880–1914. The Journal of Economic History 72 (3): 771–796.

Desposato, Scott. 2001. Legislative politics in authoritarian Brazil. Legislative Studies Quarterly 26: 287–317.

Dowdle, Michael. 1997. The constitutional development and operations of the National People’s Congress. Columbia Journal of Asian Law 11 (1): 1–125.

Gandhi, Jennifer. 2008. Political institutions under dictatorship. Cambridge University Press.

Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski. 2007. Authoritarian institutions and the survival of autocrats. Comparative Political Studies 40 (11): 1279–1301.

Geddes, Barbara. 2006. Why parties and elections in authoritarian regimes? Revised version presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington DC.

Grimmer, Justin, and Brandon Stewart. 2013. Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Political Analysis 21 (3): 267–297.

He, Junzhi, and Leming Liu. 2013. Quanguo renda daibiao de geti shuxing yu lvzhi zhuangkuang guanxi yanjiu. Fudan Xuebao [Shehui Kexue Bao] 2: 113–121 (In Chinese).

Heitshusen, Valerie, Garry Young, and David Wood. 2005. Electoral context and MP constituency focus in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. American Journal of Political Science 49 (1): 32–45.

Heurlin, Christopher. 2016. Responsive authoritarianism in China: Land, protests, and policy making. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hou, Yue. 2019. The private sector in public office: Selective property rights in China. Cambridge University Press.

Hough, Jerry, and Merle Fainsod. 1979. How the Soviet Union is governed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Huang, Dongya, and Quanling He. 2018. Striking a balance between contradictory roles. Modern China 44 (1): 103–134.

Kamo, Tomoki, and Hiroki Takeuchi. 2013. Representation and local people’s congresses in China: A case study of the Yangzhou municipal people’s congress. Journal of Chinese Political Science 18 (1): 41–60.

Keefer, Philip, and Stuti Khemani. 2009. When do legislators pass on pork? The role of political parties in determining legislator effort. American Political Science Review 103 (1): 99–112.

Kerevel, Yann. 2015. (Sub)national Principals, Legislative Agents: Patronage and Political Careers in Mexico. Comparative Political Studies 48 (8): 1020–1050.

Landry, Pierre, Xiaobo Lü, and Haiyan Duan. 2018. Does Performance Matter? Evaluating the Institution of Political Selection along the Chinese Administrative Ladder. Comparative Political Studies 51 (8): 1074–1105.

Li, Xiangyu. 2015. Zhongguo renda daibiao xingdong zhong de ‘fenpei’ zhengzhi: Dui 2009–2011 nian G sheng shengji renda dahui jianyi he xunwen de fenxi. Kaifang Shidai 4: 140–156 (In Chinese).

Li, Hongbin, and Li.-an Zhou. 2005. Political Turnover and Economic Performance: The Incentive Role of Personnel Control in China. Journal of Public Economics 89: 1743–1762.

Liu, Dongshu. 2020. “The Strategic Balance Between the Public and Allies: A Theory of Authoritarian Distribution in China.”PhD diss., Syracuse University.

Lu, Jie, and Tianjian Shi. 2015. The Battle of Ideas and Discourses before Democratic Transition: Different Democratic Conceptions in Authoritarian China. International Political Science Review 36 (1): 20–41.

Lü, Xiaobo, Mingxing Liu, and Feiyue Li. 2020. Policy Coalition Building in an Authoritarian Legislature. Comparative Political Studies 53 (9): 1380–1416.

Ma, Jun, and Muhua Lin. 2015. ‘The Power of the Purse’ of Local People’s Congresses in China: Controllable Contestation under Bureaucratic Negotiation. The China Quarterly 203: 680–701.

MacFarquhar, Roderick. 1998. Provincial People’s Congresses. The China Quarterly 155: 656–667.

Magaloni, Beatriz. 2008. Credible Power-Sharing and the Longevity of Authoritarian Rule. Comparative Political Studies 41 (4/5): 715–741.

Malesky, Edmund, and Paul Schuler. 2010. Nodding or Needling: Analyzing Delegate Responsiveness in an Authoritarian Parliament. American Political Science Review 104 (3): 482–502.

Manion, Melanie. 2008. When Communist Party Candidates Can Lose, Who Wins? The China Quarterly 195 (1): 607–630.

Manion, Melanie. 2015. Information for Autocrats: Representation in Chinese Local Congresses. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Martin, Shane. 2011. Using Parliamentary Questions to Measure Constituency Focus: An Application to the Irish Case. Political Studies 59: 472–488.

Micozzi, Juan. 2009. “The Electoral Connection in Multi-Level Systems with Non-Static Ambition.” PhD diss., Rice University.

Micozzi, Juan. 2014. From House to Home: Strategic Bill Drafting in Multilevel Systems with Non-Static Ambition. The Journal of Legislative Studies 20 (3): 265–284.

O’Brien, Kevin. 1994. Agents and Remonstrators: Role Accumulation by Chinese People’s Congress Deputies. The China Quarterly 138: 359–380.

Rosas, Guillermo, and Joy Langston. 2011. Gubernational Effects on the Voting Behavior of National Legislators. The Journal of Politics 73 (2): 477–493.

Russo, Federico. 2011. The Constituency as a Focus of Representation: Studying the Italian Case through the Analysis of Parliamentary Questions. The Journal of Legislative Studies 17 (3): 290–301.

Samuels, David. 2003. Ambition, Federalism, and Congressional Politics in Brazil. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schuler, Paul. 2020. Position Taking of Position Ducking? Comparative Political Studies 53 (9): 1493–1524.

Schuler, Paul, and Edmund Malesky. 2014. “Authoritarian Legislature.” In The Oxford Handbook of Legislative Studies, eds. Shane Martin, Thomas Saalfeld, and Kaare Strøm, 676–695. Oxford University Press.

Shi, Weimin, and Liu, Zhi. 2004. Jianjie xuanju [Indirect Elections]. Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe. (In Chinese)

Stein, Robert, and Kenneth Bickers. 1994. Congressional Elections and the Pork Barrel. The Journal of Politics 56 (2): 377–399.

Sun, Ying. 2014. Municipal people’s congress elections in the PRC: A process of co-optation. Journal of Contemporary China 23 (85): 183–195.

Svolik, Milan. 2012. The politics of authoritarian rule. Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, Michelle. 1992. Formal versus informal incentive structures and legislator behavior. The Journal of Politics 54 (4): 1053–1071.

Tromborg, Mathias, and Leslie Schwindt-Bayer. 2022. A clarity model of district representation: District magnitude and pork priorities. Legislative Studies Quarterly 47 (1): 37–52.

Truex, Rory. 2014. The returns to office in a ‘rubber stamp’ parliament. American Political Science Review 108 (2): 1–17.

Truex, Rory. 2016. Making autocracy work. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Uslaner, Eric. 1985. Casework and institutional design: redeeming promises in the promised land. Legislative Studies Quarterly 10: 35–52.

White, Stephen. 1980. The USSR Supreme Soviet: A developmental perspective. Legislative Studies Quarterly 5 (2): 247–274.

Xia, Ming. 1997. Informational efficiency, organisational development and the institutional linkages of the provincial people’s congresses in China. Journal of Legislative Studies 3 (3): 10–38.

Zhang, Changdong. 2017. Reexamining the electoral connection in authoritarian China. The China Review 17 (1): 1–27.

Zittel, Thomas, Dominic Nyhuis, and Markus Baumann. 2019. Geographic representation in party-dominated legislatures. Legislative Studies Quarterly 44 (4): 681–711.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the two anonymous reviewers who provided valuable suggestions for the revision of this article. I thank Melanie Manion, Shane Martin, Junzhi He, Chuanmin Chen, and Xiangyu Li for their comments and insights on this paper. An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2019 American Political Science Association annual conference. I also thank Liting Pan, Linchuan Zhang, Jingyan Fei, and Guangyao Deng for their research assistantship on this project. All errors remain my own.

Funding

Sponsored by MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (Project No. 17YJCZH278).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zuo, C.(. Legislator Attributes and Advocacy Focus: Non-electoral Sources of Parochialism in an Indirectly-Elected Legislature. St Comp Int Dev 57, 433–474 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-022-09373-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-022-09373-w