Abstract

The recent disruption of global supply chains and its ripple effects has led to multiple new, often conflicting, demands from governments, businesses, and society for more resilient supply chains, thereby elevating the debate about supply chains to a broader institutional level. As a response, this article aims to broaden how supply chain scholars view decision-making for supply chain resilience from an institutional perspective – in particular, using the construct of institutional complexity. We argue that the inherent complexity in supply chains, consisting of multiple organizations and multiple institutional environments, represents a different playing field and results in different responses, in particular when confronted with disruptions. We provide a systematic and structured understanding of how the interactions of institutional logics, influenced by field-levels structures and processes, impact global supply chains and its constituents. Using existing literature on institutional complexity and works on the effects of institutional logics, we present not only field-level structures and attributes influencing and shaping institutional logics in the supply chain, but also discuss and contrast existing theories and concepts by highlighting the differences between supply chain and organizational responses both on an institutional and an overarching operational level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The disruption of global supply chains and its ripple effects are increasingly recognized as a significant risk to the world economy at both an institutional and organizational level (Katsaliaki et al. 2021; Scheibe and Blackhurst 2018; Dolgui et al. 2018). In particular, the systemic risk of global supply chain disruptions seems to have been underestimated. This has led to an increase in institutional pressures and changes due to the challenges from both the Covid-19 pandemic and from the Ukraine crisis. For example, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has disrupted the wheat supply chains to many African countries that rely on Russia and Ukraine for a significant percentage of their wheat (UNCTAD 2022). This has led to higher world prices for key commodities and also worsened the food security crisis in Africa. As a response, governments, businesses, and related institutions have called for and engaged in various activities to support, restructure, and/or adapt global trade flows for more secure or resilient supply chains (Bier et al. 2020; Yu et al. 2021; Beer et al. 2022).

We argue that the recent disruptions represent a turning point for global supply chains and associated globalization. In contrast to former disruptions, the current ripple effects affect organizations and actors at a broader institutional level. Although global supply chains are interwoven in the world economy, institutions and supply chains function in the context of the transnational logics of politics and commerce, and prescribe different behaviors. As such, institutional responses to support, restructure, and/or adapt global supply chains differ and are often contradictory (Kovács & Falagara Sigala, 2021; Trautrims et al., 2020). The implications of disrupted supply chains greatly increase uncertainty for governments, business, and society and lead to multiple new, and often conflicting, demands in a global supply chain context.

From an institutional view, these supply chains are confronted with so-called institutional complexity, i.e. multiple, and often conflicting so-called institutional logics. Institutional logics represent a set of organizing principles in a given setting and reflect the “assumptions and values, usually implicit, about how to interpret organizational reality, what constitutes appropriate behavior and how to succeed” (Thornton 2004, p.70). In other words, institutional logics underpin the appropriateness of organizational practices at particular moments, which are influenced by multilevel political, cultural, and social aspects of organizational behavior (Lounsbury and Ventresca 2003). In the current dynamic environment, organizations and their actors are subject to multiple competing logics and this generates challenges and tensions for supply chains (Sayed et al. 2017; Weisz et al. 2023; Magliocca et al. 2022).

Institutionalists argue that pre-Covid-19 global supply chains represented a rather mature field, which was characterized by stable priorities between logics due to stable trade routes and predictable production outcomes (Wooten and Hoffman 2008; Herold et al. 2021a). However, since then, the scale of disrupted global supply chains has challenged the priorities in the field, leading to uncertainty and thus to new and sharp contestation between emerging logics because actors can prioritize logics that favor their normative beliefs or their material interests (Greenwood et al. 2011; Raynard 2016). The disruptions and the associated ripple effects along the supply chain reveal institutional complexity and impact the flow of goods, requiring a response from supply chains (Richey et al. 2022).

However, despite the acknowledgement of institutional influences as critical factors, structural recognition of how global supply chains and their members react at an institutional level is largely missing (Kauppi 2013; Herold et al. 2021a). While institutional scholars recognize that supply chains are often exposed to multiple and sometimes competing logics (Tsvetkova 2021; Glover et al. 2014; Saldanha et al. 2015; Herold 2018b), the existing literature makes no systematic predictions about the way in which global supply chains respond to such conflicts at a broader institutional level. In fact, existing research on institutional complexity has focused mostly on organizational responses (Greenwood et al. 2011; Oliver 1991; Thornton and Ocasio 2008).

In contrast to existing theory that investigates organizational responses, categorizing supply chain responses is more complex, because they comprise collaborations with multiple organizations and their associated multi-tier suppliers, various political and cultural layers, each with different logics and demands. In the light of the recent disruptions stemming from Covid-19 as well as from the Ukraine crisis, we argue that the institutional view of supply chain responses differs from the traditional organizational view because of three elements. First, supply chains are more vulnerable to disruptions due to the inherent connectedness between direct supply chain partners and between the various supply chain layers and tiers (Scheibe and Blackhurst 2018; Mena et al. 2013). In other words, while a single organization may be able to isolate a peripheral disturbance at the organizational level, the structure of complex global supply chains leads to immediate consequences and the potential expectations of actors at a broader institutional level. Second, the complexity of supply chains is strongly linked to the complexities of global trade and the associated regulations, customs tariffs, and regional politics. For example, global supply chains are more directly exposed to the struggle (Gros 2019) for technological and geo-strategic dominance between countries and regions, thereby adding another layer of complexity to the consequences of supply chain disruptions. Third, the inherent flexibility in supply chains may provide a range of immediate responses to global disruptions. In other words, while a single organization chooses a response according to their dominant logic, the flexibility of supply chains may encourage the emergence of new demands and expectations.

The current study aimed to extend research on institutional complexity in the supply chain literature. Our interest lay in how supply chains reacted to the tensions of different members along the supply chain and to institutional complexity. Advancing the view of Greenwood et al. (2011), we ask: “How do supply chains experience and respond to these competing, socially constructed, demands and expectations?”.

More specifically, the aim of this study was to provide a systematic and structured understanding of how the interactions of institutional logics—influenced by field-level structures and processes—impacted global supply chains and how supply chains responded. We elaborated on these pressures, in particular how the mature field of manifested pre-Covid-19 global supply chains, represented by relatively stable logics, shifted to a field that faced new ideas and associated actors and organizations, thus leading to uncertainty and new multiple demands for supply chains to function. We argue that an institutional lens provides a so-far-neglected theoretical foundation to examine the implications of disrupted supply chains, thereby offering an opportunity to extend supply chain research to a broader institutional level.

The contribution is threefold: First, we expand and extend research on institutional complexity to supply chains. While existing literature in this arena mainly focuses on organizational reactions, we argue that the inherent complexity in supply chains—consisting of multiple organizations and multiple institutional environments—represents a different playing field resulting in different responses. Second, we categorize the institutional influences on supply chains and thereby identify specific characteristics that have an impact on the extent of institutional complexity within the field. The categorization and identification of institutional influences provides a structured theoretical foundation to better understand not only the changes in the institutional environment, but also how supply chains can adapt their practices to respond to changes. Third, we illustrate supply chain responses to institutional complexity at both an institutional and an overarching operational level. This study thereby addresses the inherent uncertainty associated with decision-making and provides clarity about supply chain implications.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: In the next section, we present and discuss the main structural characteristics of institutional complexity in the context of supply chains and elaborate on the logics and influences. Then, we provide an overview about the attributes that impact supply chain responses stemming from institutional pressures at the field-level. This is followed by a presentation of supply chain responses to institutional complexity and its multiple logics and demands.

2 Institutional complexity in supply chains

Global supply chains are influenced by multiple actors including governments, businesses, and other organizations. During a disruption phase, the influences of old and new actors result in an institutionally complex environment where supply chains are shaped by the field in which they operate. The field represents “the central construct (Wooten and Hoffman 2008, p. 130) within institutional theory and analysis, because it provides the context-related sets of meaning and normative criteria that legitimize the courses of action. In other words, the pressures imposed on supply chains by various actors are fundamentally shaped by processes within an organizational field (Scott 2013).

For the purpose of our study, it was important to define global supply chains because they represent the “lifeblood of trade and economic activity” (WTO 2022). Extending the view of Rodrigue et al. (2016) to an institutional level, we define global supply chains as a globalization effort, reflecting the strategies of governments and businesses to optimize manufacturing expenses by shifting production to specialized and developing countries in order to gain a competitive advantage at both an organizational and an institutional level.

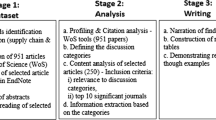

These global supply chains are influenced by institutional patterns, which can be identified from the relationships among logics, fields, and supply chains (see Fig. 1). We argue that the aggregation of responses to institutional complexity can have significant effects on both the field structure and the supply chain attributes. It is important to highlight that supply chain responses, i.e., how the supply chain reacts to external pressures, have feedback effects on the field structure and the attributes, with potential changes to institutional complexity. As such, we advance Greenwood et al.’s (2011) framework by adding another layer of influences and complexity to institutional demands. The original framework does not include a direct feedback link between organizational responses and attributes, i.e., all changes to institutional complexity and the associated attributes are driven by changes in the field structure. In contrast, our framework highlights the potential direct influence of supply chain responses on supply chain attributes. We show that supply chain responses may also directly influence the field positioning, power, and identity, in particular during times of disruption. So far, institutionalists have focused on the analysis of top-down effects owing to external pressures stemming from institutional logics but have paid little attention to how responses may systematically lead to field-level change. Thus, our framework provides a theoretical foundation to examine the influence of supply chain response on both the field structure and the supply chain attributes.

(adapted from Greenwood et al. 2011)

Institutional complexity and supply chain responses.

2.1 The role of institutional logics during supply chain disruptions

Pre-Covid-19 supply chains represented relatively mature fields where inter-organizational relationships were stable and the interaction between actors along the supply chain consisted of clear and identifiable patterns (Mena et al. 2013; Purdy et al. 2019). In stable environments, institutional complexity tends to be lower, simply because the actors have found a consensus and the tensions in the field stemming from competing logics have been solved (Pache and Santos 2013; Herold et al. 2019). These mature fields are further characterized by expectations and demands that are more predictable and consist of regularized practices (Lawrence and Phillips 2004).

Institutionalists often assume that mature fields and the associated inherent stability is the result of overarching dominant logics that dictate behavior in the field (Besharov and Smith 2014; Smets et al. 2012; Thornton and Ocasio 2008). In fact, although global supply chains consist of multiple logics, the stability in mature fields stems from the predictability and the understanding of the relationship between these institutional logics (Herold et al. 2021a; Annala et al. 2019). In a global supply chain context, while governments and businesses often do not agree how global trade and globalization should be governed and organized (Free and Hecimovic 2021), they adopt mechanisms to deal with the tensions that lead to the coexistence of multiple logics. As such, a relatively consistent and predictable set of appropriate internal practices and structures are developed in response to institutional demands, despite competing logics. In other words, in mature fields, complexity can be predicted and this enables supply chains to learn how to react and manage these tensions, thereby mitigating institutional complexity (Bui et al. 2021; Busse et al. 2017; Marzantowicz et al. 2020).

In contrast, disrupted global supply chains and the impact of the ripple effect are characterized by an inherent uncertainty, not only between supply and demand, but also in institutional arrangements (Wieland and Durach 2021; Dolgui et al. 2018; Herold and Lee 2019; Marzantowicz 2020). Thus, disruption rewrites the rules for global supply chains and questions the legitimacy of supply chain activities and boundaries with unknown implications (Manuj and Mentzer 2008). In a field that is characterized by disruption and the search for new legitimate activities, formerly excluded or neglected actors may then enter the field with new ideas and new demands, further complicating the hierarchy of logics. The emergence of new actors leads to a more fragmented and a more unpredictable environment, thus increasing institutional complexity along the supply chain (Kano et al. 2022; Linnenluecke 2017; Marzantowicz and Nowicka 2021). A new field structure emerges that is influenced by the new actors and their demands along the supply chain. In the following section, we elaborate on how we can categorize and describe the field structure changes stemming from the disruption of global supply chains.

2.2 Categorizing the influence of field structure on disrupted supply chains

In the early years of institutional research, studies identified approaches to categorize the influences of and changes in field-level structures (Meyer et al. 1987; Meyer and Rowan 1977). In particular, these approaches distinguished the degree of influence between the institutional settings on supply chains and allowed a more nuanced examination of the link between field-level structures and institutional complexity; based on their degree of (a) fragmentation, (b) formal restructuring/rationalization, and (c) centralization/unification.

First, the degree of fragmentation depends on “the number of uncoordinated constituents upon which an organization is dependent for legitimacy” (Greenwood et al. 2011, p. 337). In other words, uncoordinated actors, audiences, or organizations are represented in the field by multiple institutional logics, thereby increasing fragmentation and complexity. From a supply chain perspective, Ihle et al. (2020) contend that the disruptions caused by the pandemic led to a unprecedented fragmentation of international and national food distribution systems, resulting in complex pressures and competing demands from food retailers, wholesalers, farmers, consumers, and policymakers. Similarly, Prakash (2022) found that the fragmentation caused by supply chain disruption negatively impacted existing supply chain networks, opening the door to new actors and thus increasing complexity along the supply chain.

Second, rationalization refers to the degree of formal structuring, i.e., to what extent the pressures on supply chains and their members are informally or formally organized. Meyer et al. (1987) argue that institutional complexity is influenced by the degree of “formally organized interests, sovereigns, and constituency groups, as opposed to environments made up of less formally organized groups, communities, or associations” (p. 188). This indicates that formalized pressures lead to a lower complexity due to the stable coordination and concerted action of organizational members. From a supply chain perspective, Flynn et al. (2016) found that formalized structures could diminish the uncertainty among differentiated supply chain members and formalization thus “strengthens a supply chain’s behavioral response repertoire by implicitly stipulating the level, frequency and quality of internal and external communication.” (p. 12). In the same vein, Brandenburg and Rebs (2015) argue that the formalization of supplier management can drive a coordinated and more effective response to the sustainability challenges in supply chains. As a result, a more formalized structure sharpens institutional demands and leads to a more calculable response, thereby potentially reducing complexity in the field.

Third, the degree of centralization refers to the hierarchy and the associated power structure of institutional actors (Greenwood et al. 2011). Traditionally, centralization is supposed to reduce complexity because “the environment becomes more centralized but also more unified. The organizational rules […] become more clear, better specified, more uniform and integrated than before” (Meyer et al. 1987, p. 190). In other words, conflicting demands between actors are solved at a high level, either by dominant actors in the field or by reaching a consensus between field-level members, leading to lower institutional complexity (Litrico and David 2017). In a supply chain context, however, Flynn et al. (2016) argue that centralization hinders supply chain integration, because the decision-making is undertaken by only a few actors, thereby neglecting the expertise of other members along the supply chain. In a centralized structure, therefore, employees rely on top management for guidance, instead of using the wider network of sources needed for integration. Thus, although the empirical link between field-level centralization and the supply chain experience of complexity points to lower complexity, centralization may affect the integration and subsequent efficiency of a supply chain negatively.

Scholars argue that these three approaches provide a first step to compare and analyze the differences between fields, but that more dynamic and substantive factors and more elaborated frameworks are necessary to systematically investigate complexity in the field. In other words, we need to examine the structural conditions to better understand the influences on complexity and how supply chains may respond.

3 Supply chain attributes that influence institutional complexity

To better understand how institutional complexity influences the supply chain, Greenwood et al. (2011) suggest examining the supply chain according to specific attributes, in particular the supply chain’s position in the field, its ownership and governance, and its identity.

3.1 Positioning

How supply chains respond to institutional complexity can be distinguished by their position in the field, namely whether the supply chain plays a peripheral role or a central role (Battilana et al. 2009; Leblebici et al. 1991; Herold 2018a). Before the Covid-19 disruptions, global supply chains were seen as fundamental for globalization, but were less likely to experience greater institutional complexity, simply because their peripheral status made them subject to lower institutional expectations. Global supply chains were also less likely to receive the type of policing that required a reaffirmation of (Zhu and Morgan 2018; Chen and Paulraj 2004). Because global supply chains operate in different areas and regions, they are subject to multiple institutional logics or even different organizational fields. Thus, Greenwood and Suddaby (2006) argue that “a network position that bridges fields lessen institutional embeddedness by exposing actors to inter-institutional incompatibilities, increasing their awareness of alternatives” (p. 38). As a consequence, global supply chains prior to Covid-19 had an increased scope for flexibility and discretion to respond to institutional demands.

The Covid-19 disruption and its ripple effects changed this status and positioned global supply chains more centrally in the field, i.e., supply chains were confronted with increasing visibility and media attention (Ivanov and Das 2020; Herold et al. 2021b; Kano et al. 2022). The new-found awareness of the importance of global supply chains led to an increased scrutiny from actors or stakeholders who influence or are influenced by supply chains, leading more demands and competing logics, and increasing institutional complexity (Richey et al. 2022; Wieland and Durach 2021; Massari and Giannoccaro 2021). This contradicts existing institutional theory, which argues that a more central role is linked to stable, established institutional arrangements and less complexity (Leblebici et al. 1991; King 2008; Besharov and Smith 2014; Greenwood et al. 2011; Greenwood and Suddaby 2006). For supply chains, this claim seems to be questionable, because the positioning of the supply chain as a central element leads to an increase in complexity due to the emergence of new actors and demands in the field.

This discussion, in the context of supply chains, underscores the relevance of the field position as an attribute to examine institutional complexity. The different positioning reflects the extent to which complexity is experienced and how responses are shaped. However, it can be argued that the reactions of supply chains, in contrast to the theory of individual organizations, are shaped differently due to the inherent complexity of global trade. As such, a shift to a more central position of global supply chains in the field increases the contradictory institutional prescriptions and also the discretion of responses.

3.2 Power

Another attribute shaping how supply chains respond to institutional complexity is the relative degree of power in the supply chain of a member or group of members involved in decision-making. Decision-makers in supply chain are likely to reflect the interests of the most powerful group (Börjeson and Boström 2018; Scott 2013). As a result, those members with power may be able to dictate the response to institutional complexity that is likely to reflect the members’ interests (Power 2005; Fredrickson 1986). In other words, the more powerful members in the supply chain choose which logic(s) will be prioritized and how the responses to multiple logics are shaped.

Greenwood et al. (2011) identified two approaches to examine the influences of power on institutional complexity: ownership and governance. For ownership, the main argument is that responses to institutional complexity are “affected by its dependence upon important institutional actors” (p. 345). In other words, organizations align their responses to the preferences of those in power. From a global supply chain perspective, however, the worldwide network and its exposure to the multiple logics across different continents and regions may make it difficult to clearly identify a power hierarchy (Busse et al. 2017; Wycisk et al. 2008). Rather, the influences are based on what Greenwood and Hinings (1996) call the distribution of power across different groups and members. As a result, the one ownership is replaced by a more complex network of owners along the supply chain with an enhanced need for collaboration, thereby increasing complexity compared with the traditional organizational approach. The challenge of collaboration and dealing with inherent power structures has been a core concern in the supply chain literature (Ralston et al. 2017; Soosay and Hyland 2015).

From a governance perspective, the responses to institutional complexity depend on the role of different positions and the regulatory context (Shipilov et al. 2010; Lounsbury et al. 2021). For example, Fligstein (1990) found that chief executives’ competencies were strongly aligned with the prescriptions of the regulatory context. As a result, companies reflected the chief executives’ perspective and their preference for certain logics in the companies’ strategies and decisions. From a supply chain perspective, scholars agree that the border-crossing nature of global supply networks and a central position represent major governance challenges because members and actors have to deal with an increasing range of tools including managing codes of conduct, auditing procedures, product information systems, and/or procurement guidelines (Boström et al. 2015; Thürer et al. 2020). To address these challenges, studies suggest developing formalized / more professional arrangements including multi-stakeholder coalitions (Mathivathanan et al. 2018), build flexibility to adapt to global governance arrangements (Boström et al. 2015; Christopher and Holweg 2011), supplement effective monitoring and enforcement mechanisms (Strange and Humphrey 2019) or to establish programs to build compliance capacity (McGrath et al. 2021). These institutional demands from a governance perspective underline the role of power, in particular because these professional logics can be regarded as field-level logics and thus stabilize arrangements and reduce complexity.

3.3 Identity

A third attribute that influences responses to institutional complexity is identity identity (Kodeih and Greenwood 2014; Herold et al. 2023b), which can be defined a set of claims to “institutional standardized social categories” (Whetten and Mackey 2002, p. 397). Thus, identity is about being a member (or claiming to be a member) of certain social categories at the field level, e.g., being labeled a bank or an accounting company. These labels represent socially prescribed categories that are associated with certain characteristics. For example, a marketing company is associated with creativity, while a bank is associated with trust. Institutionalists argue that identities, in that sense, influence the prioritization of demands and expectations because actions conform to established existing practices (Czinkota et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2020). Thus, responses to institutional complexity are likely to be shaped by the perceived legitimate practices in the respective institutional environment and how they fit into the given social category.

From a supply chain perspective, we know little about identity and how it affects responses to institutional complexity (Wessel et al. 2016; Kinra and Kotzab 2008b). It can be argued that supply chains, per se, do not have an identity as they consist of a complex network of various organizations and thus of various identities. However, there are no studies that examine the impact of identity on supply chains and we suggest that, if identity plays a role in supply chains, it is most likely related to the transportation and logistics aspect (Kinra and Kotzab 2008a; Rose et al. 2016). For example, the availability of different transportation modes and the specialization of certain logistics companies influences their responses to institutional complexity (Herold et al. 2023a). Similar to other industries, the discretion of the response is limited to the capacities and capabilities of the respective transportation or logistics companies. For example, FedEx Express, as an express air freight provider, will most likely respond with flexibility around flight operations, while Maersk, a sea transport provider, will limit its responses to container shipping and try to accommodate the various demands within its organizational capacity.

In the context of identity and its responses to institutional complexity, the size of the respective transportation or logistics providers may also play a role. Studies found that large, multinational companies such as FedEx Express, Maersk, or Kuehne & Nagel, have the ability to deviate from institutional demands because these companies act outside the control of regulatory agents (Greenwood and Suddaby 2006). In other words, the size of each of these companies provides “a measure of immunity from institutional pressures, providing it with greater discretion over how, if at all, to respond to them” (Greenwood et al. 2011, p. 341). A strong sense of identity thus reinforces the company’s confidence to either comply with or ignore external pressures, thereby providing a greater range of responses to institutional complexity.

4 Supply chain responses to institutional complexity

From the discussion above, it is clear that a response depends on the multiple logics that are represented in the supply chain. Existing literature tells us also that the response is related to the extent of the logics voice, i.e., the outcome will be determined by the relative distribution of power among the members or groups within the supply chain (Ireland and Webb 2007; Touboulic et al. 2014). However, as Oliver (1991) points out, it is not only important how competing demands are given voice, but also how the voice is linked to perceived legitimate actions in the field.

We argue that one way for supply chains to respond to institutional complexity is to emerge as “institutions in their own right” (Kraatz and Block 2008, p. 251). By building on their own identity, supply chains may be able to immunize themselves against institutional pressures. In other words, the supply chain can detach itself from the institutional setting to a certain degree. However, this response may have major implications for social legitimacy. A withdrawal of a social endorsement may even be a threat to survival; thus, the response must be within the boundaries of perceived legitimacy in the field (Suchman 1995; Czinkota et al. 2014).

A more likely response is, therefore, the compartmentalizing of various sections in the supply chain (e.g., different regions or political environments), with each section giving preference to certain logics (Pratt and Foreman 2000). This decoupling along the supply chain allows the various members to respond more individually to institutional complexity in the respective sections (Schäffer et al. 2015). Thus, members or groups are able to frame messages that are aligned with the respective dominant logics to avoid social penalties penalties (Greenwood et al. 2011). More specifically, in these sections, which Simsek (2009) calls structurally differentiated hybrids, separate units or subunits give preference to different logics, thereby providing legitimate responses to various mindsets and normative processes and practices. Although research on structural hybrids is very limited, it can be concluded that hybrid structures may be seen as legitimate by field-level actors and may also perform effectively (Rao et al. 2003; Pache and Santos 2010).

This approach extends the supply chain literature on responses to institutional complexity, because “most empirical studies assume or imply that organizations enact single […] responses” (Greenwood et al. 2011, p. 351). However, in the supply chain, members will “find heterodox ways of responding to the accountability demands of [their] environment” (Binder 2007, p. 567). In fact, supply chains have to respond in hybrid structures as the network comprises various professional disciplines and needs to balance these professional demands with commercial goals (Doherty et al. 2014). Furthermore, supply chains need to consider politics and their respective logics of norms, both in their relationship with political decision-makers as well as with the employees and workers where the supply chain is located (Klein et al. 2007).

An alternative response to institutional complexity is for supply chains to increase their ability to adapt to drastic changes in the business environment using “structural flexibility” (Christopher and Holweg 2011). Traditionally, any supply chain variability was viewed as a threat for operations, leading to lean practices, push-based production strategies and outsourcing (Ivanov and Dolgui 2020; Wieland 2021). The main argument behind the traditional approach to supply chain management was “to reduce cost through increased control, which in a stable world certainly does enhance profitability” (Christopher and Holweg 2011, p. 69). During disruptions, however, controlling efforts may lead to rigidity along the supply chain, causing problems beyond the supply chain on an institutional level (Mishra et al. 2021). Incorporating structural flexibility means accepting and dealing with institutional complexity and better understanding the impact of disruptions.

In order to have a supply chain response that is flexible to operational and institutional demands, Christopher and Holweg (2011) suggest accepting disruptions and their associated uncertainty as a given, so the risk can be managed. For example, to build structural flexibility, supply chain managers may use a different manufacturing approach. Manufacturing companies in the US traditionally outsourced their manufacturing to China and shipped the finished goods back to the US with frequent deliveries. However, studies show that small-scale manufacturing plants have several benefits (Pil and Holweg 2003). Thus, flexibility can be achieved by still using China as the main source for a base load but using a local plant in the US in case of a surge in demand. This may not only provide an appropriate response to the institutional demands for a functioning supply chain but may also appease institutional constituents in the US who are demanding nearshoring.

Interestingly, the analysis of institutional effects has mainly been top-down, e.g., how logics influence practices and behavior. In contrast, little attention has been given to systematic approaches to how operational actions influence field-level changes, in particular from a supply chain perspective. In other words, it is not clear how a supply chain response that focuses on building structural flexibility into the supply chain network can influence and change the institutional demands. This gap in research is surprising because any responses to institutional complexity affect field structures and thus institutional pluralism. Future research should contribute to a better understanding of the extent to which supply chains in a field can influence institutionally complex situations and, thus, not only give preference to particular logics but also identify how to build a functioning supply chain.

5 Conclusion and implications

Global supply chains have been an existential part of international trade for decades. In stable times, the role of supply chains was rarely mentioned—organizations, politics, and society accepted supply chains as a mechanism to reliably and regularly deliver and supply goods along the value chain. The disruptions stemming from the Covid-19 pandemic as well as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, however, showed the vulnerability of global supply chains and led to multiple challenges at all institutional levels, thereby questioning the legitimacy of international expansion and geographical fragmentation of supply chains. From an institutional perspective, the emergence of new actors wanting to influence supply chains and the notion of legitimacy showed that supply chains have not only a technical–economic side, but also a social side. However, there has been limited discussion in the supply chain management literature of the role of institutional complexity in cognitive and normative terms and its implications for supply chain disruptions.

As a response, the current study set out to better understand how supply chains were influenced by institutional complexity along the global supply chain, in particular in times of disruption. More specifically, we sought to provide a systematic and a more structured conceptualization of how the interactions of institutional logics—influenced by field-level structures and processes—impact global supply chains and how supply chains react. Our framework provides a roadmap and insights into a wide array of institutional phenomena, ranging from instability to innovation, that drive supply chain susceptibility and resilience. By outlining how and why institutional influences affect supply chains, the framework also describes the demands and responses as “richly contextualized spaces” (Wooten and Hoffman 2008, p. 138). As such, this article advances our orientation and understanding of the interactional dynamics between institutional concepts and constructs, global trade, and supply chain disruptions, thereby advancing the theory of institutional complexity and the supply chain management literature.

By unpacking institutional complexity in and for supply chains, this study contributes to the supply chain literature and advances theory in three ways: First, we expand and extend research on institutional complexity for supply chains. While existing literature investigating responses to institutional complexity mainly focuses on organizational reactions, we argue that the inherent complexity in supply chains, consisting of multiple organizations and multiple institutional environments, represents a different playing field resulting in different responses. Second, we categorize the institutional influences on supply chains and thereby identify specific characteristics that have an impact on the extent of institutional complexity within the field. The categorization and identification of institutional influences provides a structured theoretical foundation to better understand not only the changes in the institutional environment, but also how supply chains can adapt practices to respond to changes. Third, we illustrate supply chain responses to institutional complexity both at an institutional and at an overarching operational level. This study thereby addresses the inherent uncertainty associated with decision-making and provides clarity about the supply chain implications.

Next, we identify three specific patterns of complexity that shape supply chains and classify three specific institutional responses. By doing so, we not only demonstrate how competing institutional logics contribute to the vulnerability of supply chains, but we also provide a structured institutional theoretical foundation on how supply chains respond to disruptions. The identification and classification of the institutional influences in a supply chain context highlight how the complexity of supply chains and the institutionalization of logics can impact legitimacy in the field. For example, in the patterns of complexity and in the institutional responses to supply chains, the inherent complexity of global trade and the multiple institutional environments may query how legitimacy is viewed in a supply chain context. According to Suchman (1995), legitimacy is “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (p. 574). As such, our study shows that the implementation of practices and rules at a field-level may differ between institutional environments and their different legitimacy context to an extent where Suchman’s (1995) “generalized perception” need a more nuanced definition.

Finally, by expanding and extending research on institutional complexity to supply chains, we broaden how researchers in supply chain management view supply chain disruptions. Thus, we provide managers with theoretical ways to think about supply chain disruptions and their implications for global trade. Using current research on institutional complexity and the effects of institutional logics, we not only discuss and contrast existing theories and concepts in the context of supply chains, but also provide a structured approach of supply chains responses at an institutional and operational level. We are confident that this study lays the groundwork for further research on institutional complexity in and for supply chains, thereby stimulating investigations into this neglected area of research.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Annala L, Polsa PE, Kovács G (2019) Changing institutional logics and implications for supply chains: ethiopian rural water supply. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 24(3):355–376

Battilana J, Leca B, Boxenbaum E (2009) How actors change institutions: towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Acad Manag Ann 3(1):65–107

Beer E, Mikl J, Schramm H-J, Herold DM (2022) Resilience strategies for Freight Transportation: an overview of the different transport modes responses. In: Kummer S, Wakolbinger T, Novoszel L, Geske AM (eds) Supply Chain Resilience: insights from theory and practice. Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, pp 263–272

Besharov ML, Smith WK (2014) Multiple institutional logics in organizations: explaining their varied nature and implications. Acad Manage Rev 39(3):364–381

Bier T, Lange A, Glock CH (2020) Methods for mitigating disruptions in complex supply chain structures: a systematic literature review. Int J Prod Res 58(6):1835–1856

Binder A (2007) For love and money: Organizations’ creative responses to multiple environmental logics. Theory and Society 36(6):547–571

Börjeson N, Boström M (2018) Towards reflexive responsibility in a textile supply chain. Bus Strategy Environ 27(2):230–239

Boström M, Jönsson AM, Lockie S, Mol AP, Oosterveer P (2015) Sustainable and responsible supply chain governance: challenges and opportunities. J Clean Prod 107:1–7

Brandenburg M, Rebs T (2015) Sustainable supply chain management: a modeling perspective. Ann Oper Res 229(1):213–252

Bui T-D, Tsai FM, Tseng M-L, Tan RR, Yu KDS, Lim MK (2021) Sustainable supply chain management towards disruption and organizational ambidexterity: a data driven analysis. Sustainable Prod Consum 26:373–410

Busse C, Schleper MC, Weilenmann J, Wagner SM (2017) Extending the supply chain visibility boundary: utilizing stakeholders for identifying supply chain sustainability risks. Int J Phys Distribution Logistics Manage 47(1):18–40

Chen IJ, Paulraj A (2004) Towards a theory of supply chain management: the constructs and measurements. J Oper Manag 22(2):119–150

Christopher M, Holweg M (2011) Supply Chain 2.0”: managing supply chains in the era of turbulence. Int J Phys Distribution Logistics Manage 41(1):63–82

Czinkota M, Kaufmann HR, Basile G (2014) The relationship between legitimacy, reputation, sustainability and branding for companies and their supply chains. Ind Mark Manage 43(1):91–101

Doherty B, Haugh H, Lyon F (2014) Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: a review and research agenda. Int J Manage Reviews 16(4):417–436

Dolgui A, Ivanov D, Sokolov B (2018) Ripple effect in the supply chain: an analysis and recent literature. Int J Prod Res 56(1–2):414–430

Fligstein N (1990) The transformation of corporate control. Harvard University Press

Flynn BB, Koufteros X, Lu G (2016) On theory in supply chain uncertainty and its implications for supply chain integration. J Supply Chain Manage 52(3):3–27

Fredrickson JW (1986) The strategic decision process and organizational structure. Acad Manage Rev 11(2):280–297

Free C, Hecimovic A (2021) Global supply chains after COVID-19: the end of the road for neoliberal globalisation? Acc Auditing Account J 34(1):58–84

Glover JL, Champion D, Daniels KJ, Dainty AJ (2014) An institutional theory perspective on sustainable practices across the dairy supply chain. Int J Prod Econ 152:102–111

Greenwood R, Hinings CR (1996) Understanding radical organizational change: bringing together the old and the new institutionalism. Acad Manage Rev 21(4):1022–1054

Greenwood R, Suddaby R (2006) Institutional entrepreneurship in mature fields: the big five accounting firms. Acad Manag J 49(1):27–48

Greenwood R, Raynard M, Kodeih F, Micelotta ER, Lounsbury M (2011) Institutional complexity and organizational responses. Acad Manag Ann 5(1):317–371

Gros D (2019) This is not a trade war, it is a struggle for technological and geo-strategic dominance’ CESifo Forum. ifo Institut–Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung an der …, München, pp 21–261

Herold DM (2018a) Has Carbon Disclosure become more transparent in the global Logistics Industry? An investigation of corporate Carbon Disclosure Strategies between 2010 and 2015. Logistics 2(3):13

Herold DM (2018b) The Influence of Institutional and Stakeholder Pressures on Carbon Disclosure Strategies: An Investigation in the Global Logistics Industry. Dissertation, Griffith University

Herold DM, Lee K-H (2019) The influence of internal and external pressures on carbon management practices and disclosure strategies. Australasian J Environ Manage 26(1):63–81

Herold DM, Farr-Wharton B, Lee KH, Groschopf W (2019) The interaction between institutional and stakeholder pressures: advancing a framework for categorising carbon disclosure strategies. Bus Strategy Dev 2(2):77–90

Herold DM, Ćwiklicki M, Pilch K, Mikl J (2021a) The emergence and adoption of digitalization in the logistics and supply chain industry: an institutional perspective. J Enterp Inform Manage 34(6):1917–1938

Herold DM, Nowicka K, Pluta-Zaremba A, Kummer S (2021b) COVID-19 and the pursuit of supply chain resilience: reactions and “lessons learned” from logistics service providers (LSPs). Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 26(6):702–714

Herold DM, Fahimnia B, Breitbarth T (2023a) The Digital Freight Forwarder and the incumbent: a Framework to examine disruptive potentials of Digital Platforms. Transp Res E, 103214

Herold DM, Harrison CK, Bukstein SJ (2023b) Revisiting organizational identity and social responsibility in professional football clubs: the case of Bayern Munich and the Qatar sponsorship. Int J Sports Mark Spons 24(1):56–73

Ihle R, Rubin OD, Bar-Nahum Z, Jongeneel R (2020) Imperfect food markets in times of crisis: economic consequences of supply chain disruptions and fragmentation for local market power and urban vulnerability. Food Secur 12(4):727–734

Ireland RD, Webb JW (2007) A multi-theoretic perspective on trust and power in strategic supply chains. J Oper Manag 25(2):482–497

Ivanov D, Das A (2020) Coronavirus (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) and supply chain resilience: a research note. Int J Integr Supply Manage 13(1):90–102

Ivanov D, Dolgui A (2020) Viability of intertwined supply networks: extending the supply chain resilience angles towards survivability. A position paper motivated by COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Prod Res 58(10):2904–2915

Kano L, Narula R, Surdu I (2022) Global value chain resilience: understanding the impact of managerial governance adaptations. Calif Manag Rev 64(2):24–45

Katsaliaki K, Galetsi P, Kumar S (2021) Supply chain disruptions and resilience: a major review and future research agenda. Ann Oper Res, 1–38

Kauppi K (2013) Extending the use of institutional theory in operations and supply chain management research: review and research suggestions. Int J Oper Prod Manage 33(10):1318–1345

King BG (2008) A political mediation model of corporate response to social movement activism. Adm Sci Q 53(3):395–421

Kinra A, Kotzab H (2008a) A macro-institutional perspective on supply chain environmental complexity. Int J Prod Econ 115(2):283–295

Kinra A, Kotzab H (2008b) Understanding and measuring macro-institutional complexity of logistics systems environment. J Bus Logistics 29(1):327–346

Klein R, Rai A, Straub DW (2007) Competitive and cooperative positioning in supply chain logistics relationships. Decis Sci 38(4):611–646

Kodeih F, Greenwood R (2014) Responding to institutional complexity: the role of identity. Organ Stud 35(1):7–39

Kraatz MS, Block ES (2008) Organizational implications of institutional pluralism. Sage Handb organizational institutionalism 840:243–275

Lawrence TB, Phillips N (2004) From Moby Dick to Free Willy: macro-cultural discourse and institutional entrepreneurship in emerging institutional fields. Organization 11(5):689–711

Leblebici H, Salancik GR, Copay A, King T (1991) Institutional change and the transformation of interorganizational fields: an organizational history of the US radio broadcasting industry. Adm Sci Q 36(3):333–363

Linnenluecke MK (2017) Resilience in business and management research: a review of influential publications and a research agenda. Int J Manage Reviews 19(1):4–30

Litrico J-B, David RJ (2017) The evolution of issue interpretation within organizational fields: actor positions, framing trajectories, and field settlement. Acad Manag J 60(3):986–1015

Lounsbury M, Ventresca M (2003) The new structuralism in organizational theory. Organization 10(3):457–480

Lounsbury M, Steele CW, Wang MS, Toubiana M (2021) New directions in the study of institutional logics: from tools to phenomena. Ann Rev Sociol 47:261–280

Magliocca P, Herold DM, Canestrino R, Temperini V, Albino V (2022) The role of start-ups as knowledge brokers: a supply chain ecosystem perspective. J Knowldege Manage. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-07-2022-0593

Manuj I, Mentzer JT (2008) Global supply chain risk management strategies. Int J Phys Distribution Logistics Manage 38(3):192–223

Marzantowicz Ł (2020) The impact of uncertainty factors on the decision-making process of logistics management. Processes 8(5):512

Marzantowicz Ł, Nowicka K (2021) Disruption as an element of decisions in the supply chain under uncertainty conditions: a theoretical approach. Zeszyty Naukowe Akademii Morskiej w Szczecinie

Marzantowicz Ł, Nowicka K, Jedliński M (2020) Smart „Plan B”-in face with disruption of supply chains in 2020. LogForum 16(4):487–502

Massari GF, Giannoccaro I (2021) Investigating the effect of horizontal coopetition on supply chain resilience in complex and turbulent environments. Int J Prod Econ 237:108150

Mathivathanan D, Kannan D, Haq AN (2018) Sustainable supply chain management practices in indian automotive industry: a multi-stakeholder view. Resour Conserv Recycl 128:284–305

McGrath P, McCarthy L, Marshall D, Rehme J (2021) Tools and technologies of transparency in sustainable global supply chains. Calif Manag Rev 64(1):67–89

Mena C, Humphries A, Choi TY (2013) Toward a theory of multi-tier supply chain management. J Supply Chain Manage 49(2):58–77

Meyer JW, Rowan B (1977) Institutionalized organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am J Sociol 83(2):340–363

Meyer J, Scott WR, Strang D (1987) Centralization, fragmentation, and school district complexity. Adm Sci Q 32(2):186–201

Mishra R, Singh RK, Subramanian N (2021) Impact of disruptions in agri-food supply chain due to COVID-19 pandemic: contextualised resilience framework to achieve operational excellence. Int J Logistics Manage.

Oliver C (1991) Strategic responses to institutional processes. Acad Manage Rev 16(1):145–179

Pache A-C, Santos F (2010) When worlds collide: the internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Acad Manage Rev 35(3):455–476

Pache A-C, Santos F (2013) Embedded in hybrid contexts: how individuals in organizations respond to competing institutional logics. Res Sociol Organ 39:3–35

Pil FK, Holweg M (2003) Exploring scale: the advantages of thinking small. MIT Sloan Management Review 44(2):33–39A

Power D (2005) Supply chain management integration and implementation: a literature review. Supply chain management: an International journal 10(4):252–263

Prakash G (2022) Resilience in food processing supply chain networks: empirical evidence from the indian dairy operations. J Adv Manage Res.

Pratt MG, Foreman PO (2000) Classifying managerial responses to multiple organizational identities. Acad Manage Rev 25(1):18–42

Purdy J, Ansari S, Gray B (2019) Are logics enough? Framing as an alternative tool for understanding institutional meaning making. J Manage Inq 28(4):409–419

Ralston PM, Richey RG, Grawe SJ (2017) The past and future of supply chain collaboration: a literature synthesis and call for research. Int J Logistics Manage 28(2):508–530

Rao H, Monin P, Durand R (2003) Institutional change in Toque Ville: Nouvelle cuisine as an identity movement in french gastronomy. Am J Sociol 108(4):795–843

Raynard M (2016) Deconstructing complexity: configurations of institutional complexity and structural hybridity. Strategic Organ 14(4):310–335

Richey RG, Roath AS, Adams FG, Wieland A (2022) A responsiveness view of logistics and supply chain management. J Bus Logistics 43(1):62–91

Rodrigue J-P, Comtois C, Slack B (2016) The geography of transport systems. Taylor & Francis

Rose WJ, Mollenkopf DA, Autry CW, Bell JE (2016) Exploring urban institutional pressures on logistics service providers. Int J Phys Distribution Logistics Manage.

Saldanha JP, Mello JE, Knemeyer AM, Vijayaraghavan T (2015) Implementing supply chain technologies in emerging markets: an institutional theory perspective. J Supply Chain Manage 51(1):5–26

Sayed M, Hendry LC, Bell MZ (2017) Institutional complexity and sustainable supply chain management practices. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal.

Schäffer U, Strauss E, Zecher C (2015) The role of management control systems in situations of institutional complexity. Qualitative Res Acc Manage 12(4):395–424

Scheibe KP, Blackhurst J (2018) Supply chain disruption propagation: a systemic risk and normal accident theory perspective. Int J Prod Res 56(1–2):43–59

Scott WR (2013) Institutions and organizations: ideas, interests, and identities. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Shipilov AV, Greve HR, Rowley TJ (2010) When do interlocks matter? Institutional logics and the diffusion of multiple corporate governance practices. Acad Manag J 53(4):846–864

Simsek Z (2009) Organizational ambidexterity: towards a multilevel understanding. J Manage Stud 46(4):597–624

Smets M, Morris T, Greenwood R (2012) From practice to field: a multilevel model of practice-driven institutional change. Acad Manag J 55(4):877–904

Soosay CA, Hyland P (2015) A decade of supply chain collaboration and directions for future research. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 20(6):613–630

Strange R, Humphrey J (2019) What lies between market and hierarchy? Insights from internalization theory and global value chain theory. J Int Bus Stud 50(8):1401–1413

Suchman MC (1995) Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad Manage Rev 20(3):571–610

Thornton PH (2004) Markets from culture: institutional logics and organizational decisions in higher education publishing. Stanford University Press, Standford, CA

Thornton PH, Ocasio W (2008) Institutional logics. In: Greenwood R, Oliver C, Suddaby R, Sahlin A (eds) The sage handbook of organizational institutionalism. Sage, London, pp 100–129

Thürer M, Tomašević I, Stevenson M, Blome C, Melnyk S, Chan HK et al (2020) A systematic review of China’s belt and road initiative: implications for global supply chain management. Int J Prod Res 58(8):2436–2453

Touboulic A, Chicksand D, Walker H (2014) Managing imbalanced supply chain relationships for sustainability: a power perspective. Decis Sci 45(4):577–619

Tsvetkova A (2021) Human actions in supply chain management: the interplay of institutional work and institutional logics in the russian Arctic. Int J Phys Distribution Logistics Manage.

UNCTAD (2022) ‘The Impact on Trade and Development of the War in Ukraine’. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Available at: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/osginf2022d1_en.pdf

Weisz E, Herold DM, Kummer S (2023) Revisiting the bullwhip effect: how can AI smoothen the bullwhip phenomenon? Int J Logistics Manage.

Wessel F, Kinra A, Kotzab H (2016) Macro-institutional complexity in Logistics: the case of Eastern Europe. Dynamics in Logistics. Springer, pp 463–472

Whetten DA, Mackey A (2002) A social actor conception of organizational identity and its implications for the study of organizational reputation. Bus Soc 41(4):393–414

Wieland A (2021) Dancing the supply chain: toward transformative supply Chain Management. J Supply Chain Manage.

Wieland A, Durach CF (2021) Two perspectives on supply chain resilience. J Bus Logistics 42(3):315–322

Wooten M, Hoffman AJ (2008) Organizational fields: past, present and future. In: Greenwood R, Oliver C, Shalin-Andersson K, Suddaby R (eds) The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism. Sage, London, pp 130–147

WTO (2022) ‘Easing supply chain bottlenecks for a sustainable future’ Global Supply Chains Forum. World Trade Organization. Available at: https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/events_e/report-gscforum2022_e.pdf

Wycisk C, McKelvey B, Hülsmann M (2008) Smart parts” supply networks as complex adaptive systems: analysis and implications. Int J Phys Distribution Logistics Manage 38(2):108–125

Yang Q, Geng R, Feng T (2020) Does the configuration of macro-and micro‐institutional environments affect the effectiveness of green supply chain integration? Bus Strategy Environ 29(4):1695–1713

Yu Z, Razzaq A, Rehman A, Shah A, Jameel K, Mor RS (2021) Disruption in global supply chain and socio-economic shocks: a lesson from COVID-19 for sustainable production and consumption. Oper Manage Res, 1–16

Zhu J, Morgan G (2018) Global supply chains, institutional constraints and firm level adaptations: a comparative study of chinese service outsourcing firms. Hum Relat 71(4):510–535

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Herold, D.M., Marzantowicz, Ł. Supply chain responses to global disruptions and its ripple effects: an institutional complexity perspective. Oper Manag Res 16, 2213–2224 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-023-00404-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-023-00404-w