Abstract

Many industrial firms motivate structural changes by an increased focus on core activities and reduced ownership of non-core activities. However, classifying maintenance activities as either core or non-core can be difficult, since maintenance is a support function strongly linked to the production core within a manufacturing firm. Based on a multiple case study that included four buying firms and four suppliers within the process industry, this paper investigates how the relative capabilities of the firms affect the governance decision about maintenance outsourcing. A conceptual framework built on a distinction between core-close and core-distant maintenance and between different maintenance capabilities is presented. The subsequent empirical analysis illustrates how the developed framework can be used for both analyzing and guiding firms’ decisions about outsourcing and governance regarding maintenance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Fierce competition in the global economy induces firms to strategically identify and decide on which activities should be performed internally and which would be more appropriate to outsource (Sanchís-Pedregosa et al. 2014). The rapid development of information and communication technologies has also made outsourcing accelerate and encompass almost every organizational activity (Aron and Singh 2005 and McIvor 2009), including areas such as service maintenance (Barthèlemy and Quèlin 2006; McIvor 2005; Quinn 2000). The effects that firms experience from outsourcing are, however, ambiguous (Bengtsson et al. 2009). Outsourcing has, on the one hand, been associated with negative consequences such as losing some of the capabilities that are outsourced (Bettis et al. 1992). On the other hand, the outsourcing firm is not limited to its own capabilities; it can take advantage of a stream of external ideas and capabilities it could not possibly generate itself (Quinn 2000). The decision to outsource therefore must consider the question of governance (Williamson 1999 and McIvor 2008).

Governing maintenance outsourcing relies on the interdependencies between maintenance and core production (Murthy et al. 2002). One problem here is that industry representatives often do not regard maintenance as a contributor to the core capability of a firm (Gupta et al. 2009); maintenance is inversely regarded as safe to outsource in the belief that outsourcing will not have an adverse impact on the firm’s future capabilities and performance (Maley et al. 2015). However, some researchers do indeed suggest that maintenance is close to the core operation of the firm (eg (Levery 1998). In this paper, we use a distinction motivated by Arnold (2000) and differentiate between core-close maintenance and core-distant maintenance. The distinction is firm specific and must be decided with care by management of the firm. In process industries (such as the steel industry), the capacity and the accuracy of the equipment is critical, and effective maintenance is crucial for competitiveness as well. Process industry plants are complex systems where many activities are interlinked, something that makes the decision about what is core and what is non-core difficult. Therefore, the process industry is a fruitful context for studying outsourcing decisions related to maintenance. To the best of our knowledge there is a lack of models for how to govern outsourced services that support value-adding processes such as maintenance. In addition to governance, the dearth of models includes analysis of relative capabilities. The outsourcing decision depends on the supplier’s capability to deliver the outsourced services in a superior manner compared to the outsourcing firm (McIvor 2008).

Against this background, the purpose of this paper is to investigate how firms’ relative capabilities affect the governance decision on maintenance outsourcing. Based on a multiple case study that includes four buying firms and four suppliers within the process industry, this paper investigates how the relative capability of the firms affects the governance decision on maintenance outsourcing. More specifically, the paper presents a conceptual framework that is defined by two dimensions: (1) relative technical capability and (2) relative organizational capability (eg, process maturity). The study illustrates how the capability position of the supplier affects the buying firm’s governance decision. In this paper, we conceptualize the outsourcing package, representing capability position in terms of technical and organizational capability, maintenance distinctions, and governance typology. From this, two research questions have been derived:

-

RQ1 – In what way does a distinction between core-close and core-distant maintenance affect the outsourcing decision?

-

RQ2 – How does supplier capability affect the governance of the outsourced maintenance activities?

2 Theoretical frameworks

In this paper, we conceptualize governance of maintenance outsourcing by combining the supply chain management maturity and the supply chain process maturity frameworks (SCMM/SCPM) with a typology of global value chain governance. The SCMM/SCPM is an evolutionary framework that provides a processual dimension and a way of mapping changes in the supply chain over time (Varoutsa and Scapens 2015). The governance typology provides not only an understanding of different governance alternatives but also how they are connected to a firm’s governance needs and, together with SCMM/SCPM, to the relative capability position of a supplier.

2.1 Core-close/core-distant maintenance

Industrial maintenance is one of the top five functions that are most affected by outsourcing (Quèlin and Duhamel 2003). Companies claim that maintenance is inimitable, because it involves firm capabilities that cannot be easily implemented or copied by their competitors (Maley et al. 2015), and therefore contributes to a firm’s competitive advantage. Maintenance effectiveness directly impacts plant reliability, uptime availability, and production efficiency, and therefore affects cost-related and supply reliability aspects of competitive advantage rather directly. Maintenance is often close to the core operation of a manufacturing firm. A decision to outsource maintenance is difficult because it might have a strong effect on the firm’s production efficiency and encompasses not only professional skills but also process knowledge and understanding of the interrelationship among processes in the production plant (Levery 1998). At the same time, the urgency and criticality of different maintenance activities vary due to how they relate to the core of the production.

Inspired by Arnold (2000) distinctions between core-close and core-distinct activities, this paper divides maintenance services into either core-close or core-distant. The distinction between them are built upon on two attributes; (1) Strategic importance, where core-close is defined by the maintenance activities that are directly targeted at and facilitated by the firm’s core processes, ie the processes that have a strong effect on the firm’s production efficiency, and therefore contributes to competitive advantage (McIvor 2008). Core-distant maintenance is defined as maintenance activities that target processes that are necessary and supportive, but less important for maintaining the core process efficiency. (2) Degree of specificity: according to Williamson (1991) and Arnold (2000) specificity refers to asset specificity as well as human capital specificity in terms of a high degree of knowledge, skills, and experience. Core-close maintenance mainly relates to high human capital specificity. However, core-close maintenance activities also involves a high degree of knowledge of and experience with workflows and processes of core activities within the firm or the other party (Levery 1998), which is defined as procedural asset specificity by Zaheer and Venkatraman (1995). Core-distant maintenance concerns medium or low asset specificity and refers to those skills or expertice that are not key to the success for the outcome of the firm’s or the other party’s core activities (Cox 1996; Arnold 2000).

To decide whether a form of maintenance is core-close or core-distant is tricky, but the decision is crucial for the strategic approach and for the supplier selection process (McIvor 2008). When comparing two maintenance processes to classify if they are core-close or core-distant, one of them contributes less than the other. A truck is less strategically important than vibration analysis, because in term of efficiency, quality, and costs, it contributes less to the firm’s core business. A fan could be extremely strategically important for production efficiency, while the same fan in another location in the production plant can have no strategic value at all. This implies that core-close and core-distant maintenance could have quite different effects on production efficiency (Ghayebloo and Shahanaghi 2010), and therefore must be maintained differently from both strategic and practical approaches. McIvor (2000) states that defining core activities of the business is the first step in the outsourcing decision. Determining the contribution of a process to a firm’s competitive advantage is central for the classification of core-close or core-distant maintenance, and based on that classification central for the outsourcing decision (McIvor 2000, 2008). The kind of maintenance as well as the relative capability position of the maintenance suppliers together constitutes sources of sustained competitive advantage for the firm; this underlines the need for firms to implement a value-creating relationship strategy for business-critical maintenance processes. This strategy involves the ability to select the right supplier and to build trust-based relationships (Ireland et al. 2002).

2.2 Outsourcing

There are several definitions of the term outsourcing (see overview in Gilley and Rasheed 2000). In the most far-reaching understanding, outsourcing equals “outside resource using” (Büner and Tuschke 1997 and Quinn and Hilmer 1994), which encompasses purchasing all kinds of activities, including those that have never been done internally. The term outside means creating value not within the company and a strategic focus on external resources (Arnold 2000). A narrower common understanding is that outsourcing describes the process of having an activity that was formerly done inside the organization performed by an external supplier (McIvor 2008 and Bengtsson 2008). Outsourcing has evolved into a more strategic process; collaboration, cooperation, and co-development are required to gain success (Ishizaka and Blakiston 2012). Outsourcing demands a close and long-term relationship to sustain a competitive advantage (McHugh et al. 2003) and should not be used as a synonym for contracting out. Contracting means work completed by an external supplier on a single job basis (Hätönen and Eriksson 2009), whereas outsourcing involves reliance on the external skills and capabilities of an external supplier (Kakabadse and Kakabadse 2000 and Varadarajan 2009). Madhok (2002) recognized that firms need to consider their own capability attributes and their competences prior to outsourcing. But how they should consider them is less documented in the literature.

There are many articles about outsourcing (eg, Prahalad and Hamel 1990; Quinn and Hilmer 1994; Cox 1996; McIvor 2000, 2008), most of them without any guiding methodology. The Sourcing Strategy framework by McIvor (2008) is an exception and a commonly used framework in operations management. It is built up by assessing activities in two dimensions: relative capability and the contribution to competitive advantage. According to McIvor (2008), a key strategic issue for competitiveness is understanding why one firm differs in performance from another. Building on the resource-based view of Barney (1991), he claims that competitive advantage is sustained when (a) competitors are unable to duplicate the benefits of this strategy and (b) it continues to exist after efforts to duplicate that advantage have failed. Accordingly, the decision of whether a process should be outsourced or not must be based on an evaluation of the firm’s own capability relative to competitors and suppliers. McIvor (2008) therefore argues that the analysis concerns identifying the differences between the organization and potential external process suppliers. One key issue here is the capability of the suppliers that provide core services—whether they can excel in vital processes compared with the organization itself or its competitors (Aron and Singh 2005 and Ishizaka and Blakiston 2012). However, it is not always easy to identify which services are core or non-core (Cox 1996). As the second dimension, McIvor (2008) contends that it is central to the outsourcing process to determine the contribution to competitive advantage of an activity.

2.3 Governance typology

Outsourcing creates an interfirm relationship between firm and supplier (Barthèlemy and Quèlin 2006); that is, outsourcing implies a change in how activities are governed. Governance issues concerning interfirm relationships are receiving more and more attention in the literature. The use of contracts and governance mechanisms is essential for obtaining rewards from outsourcing (Lonsdale 1999; Datta and Roy 2013; Ishizaka and Blakiston 2012). Vitasek and Manrodt (2012) state that outsourcing requires a governance structure with insights rather than oversight, involving elements of relationship management. The literature addresses different kinds of governance structures and types for a firm’s supply chain (eg, Gereffi et al. 2005 and Wathne and Heide 2004), relying on the new institutional economics literature, a branch predominantly concerned with governance and where transaction costs are located (Williamson 1998).

Maintenance must be seen as a supply chain of its own. That’s because production plant maintenance is not directly involved in the supply chain of firms’ core production but rather supports the core supply chain, in other words the production line, with corrective and preventive maintenance services. Governance structures and mechanisms must allow for flexible adaptation to changing circumstances (Williamson 1991) and uncertainty in the downstream relationships (Wathne and Heide 2004). Following Dekker (2008) and Ireland et al. (2002), firms can deal with control problems in interfirm relationships by selecting an appropriate partner. Furthermore, the partner selection phase influences both collaboration and the use of governance arrangements (Dekker 2004).

Basic governance alternatives can be based theoretically on Williamson’s institutional economics. He identified three major governance structures for economic transactions (Williamson 1985): Markets—steer transactions by the price mechanism, Hierarchies—based on centralization and directly linked with insourcing, and Hybrids—all structures in between the two others (Williamson 1999). Most other theoretical models or frameworks in the literature also have this definition of governance (eg, Arnold 2000 and McIvor 2008), although with minor differences between them. Gereffi et al. (2005) construct an analytical typology of global value chain governance based on four determinants: (1) the complexity of information and knowledge transfer required, (2) the extent to which this information and knowledge can be codified and transmitted efficiently, (3) the capabilities of actual and potential suppliers in relation to the requirements of the transaction, and (4) the degree of explicit coordination and power asymmetry. Their framework consists of five analytical governance types with markets and hierarchies as the extremes; each governance type provides a different trade-off between the benefits and risks of outsourcing. The five governance types are:

-

1.

“Market”, a typical spot-market with market linkages not completely transitory

-

2.

“Modular”, suppliers who make products to customer’s specifications

-

3.

“Relational”, networks with complex interactions between customer and suppliers, high mutual dependence and a high level of asset specificity

-

4.

“Captive”, small suppliers who are transactionally dependent on much larger customers, and

-

5.

“Hierarchy”, a governance form characterized by vertical integration and managerial control.

Gereffi et al. (2005) argue that a theory of value chain governance should allow for more than just generating different forms of interfirm coordination. It must also anticipate change in value chains, because governance structures evolve over time as the value chain does. This implies that value chains, governance typology, and structures undergo a maturity process.

2.4 Supply chain process management maturity – the influence on capability and governance

Some maturity models in the literature aim to evaluate the present situation of a firm’s ability to be competitive, set goals, allocate resources and collaborate with partners (Lahti et al. 2009). However, we are using the Supply Chain Management Maturity (SCMM) model developed by Lockamy and McCormack (2004), which was designed to measure supply chain process management skills. Arguing that the Lockamy and McCormack (2004) model relies on subjective metrics to rank the maturity levels of firms, Oliveira et al. (2011) developed a new model of SCPM called Supply Chain Process Management Maturity Model 3 (SCPM3), enabling an understanding of the precedence of the dynamics of supply chain process management skills as well as an identification of the key turning points that distinguish the maturity levels (Souza et al. 2015).

The governance will change as the supply chain moves from low maturity and a traditional buyer–supplier relationship towards a mature inter-organizational relationship and mutual dependency, characterized as a shift from an internally oriented approach to an externally oriented approach by Lockamy and McCormack (2004). The following is a short description of each SCM maturity level according to Oliveira et al. (2011) and Lockamy and McCormack (2004), along with each one’s connection to governance (Gereffi et al. 2005 and Varoutsa and Scapens 2015):

-

Foundation (Ad hoc) – The supply chain and practices are unstructured and ill-defined. This level comprises traditional arm’s-length market-based relationships characterized by a lack of close interaction and collaboration between suppliers and buyers (Varoutsa and Scapens 2015). The marketplace consists of many potential suppliers, and the main factors in the choice of supplier are the market price and market governance (Gereffi et al. 2005).

-

Structure (Defined) – Firms at this level seek to optimize their use of resources through the integration of processes. Production planning and distribution management are implemented, and the primary objective of companies at this level is the identification of critical partners and the formalization of contracts. There is no need for a sophisticated control instrument (Varoutsa and Scapens 2015), so a market governance typology is still to be expected.

-

Vision (Linked) – At this stage, companies review their functional structure and logistics processes. Cooperation among intra-company functions, vendors, and customers is in place. Efforts to identify suppliers who are encouraged to invest in the relationship and commit themselves to the supply chain (Varoutsa and Scapens 2015) are in place. Firms exchange essential information and engage some suppliers in longer contracts, and modular governance typology is needed rather than market governance (Gereffi et al. 2005). This stage is the beginning of a more collaborative relationship and can be considered the “breakthrough” phase, according to Lockamy and McCormack (2004).

-

Integration (Integrated) – At this stage of maturity the stakeholders increasingly realize the importance of relationships. The company, as well as its vendors and suppliers, takes cooperation to the process level, and by working more closely there is a need for more information sharing (Caglio and Ditillo 2012). The objective of the companies at this level is to build a supply chain based on collaborative behavior, and the suppliers are involved in the early stages of customer-specific product design, especially in modular products (Stevensson and Spring 2009). Partners are integrated through the sharing of risk and rewards and long-term shared commitment and goals. A modular governance typology is to be expected (Gereffi et al. 2005).

-

Dynamic (Extended) – This stage is characterized by the systematic integration of the supply chain to allow for dynamic behavior based on the continuous improvement of processes. Collaboration with suppliers is established, and the focus is on partnership based on mutual interests, goals, and respect (Varoutsa and Scapens 2015). The focus is on the relationship with, rather than the performance of, the supplier (Johnsen et al. 2008), and advanced management practices will be in place (Varoutsa and Scapens 2015) such as cross-organizational teams (Lockamy and McCormack 2004). Sharing of strategic information is necessary, especially for the governance of the relationship (Varoutsa and Scapens 2015). The expected governance typology is a relational one (Gereffi et al. 2005).

When building trust-based interfirm relationships, such as when moving from a traditional arm’s-length relationship to a more mature supply chain including partnership with suppliers, the firm needs to reconstruct its supply chain practices. The studies by Caglio and Ditillo (2008) and Varoutsa and Scapens (2015) both find that different forms of governance are needed at each maturity phase. Consequently, supply chain reconstruction is likely to be accompanied by governance changes (Varoutsa and Scapens 2015). Each stage of maturity is equal to a specific level of organizational capability, such as the capability to interact and collaborate with the supplier or customer effectively, and the capability position is itself a combination of technical and organizational capabilities.

2.5 Summing up the conceptual framework

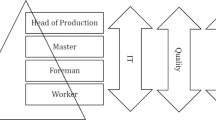

Based on the previous discussion, we present a theoretical framework incorporating governance typology for global value chains by Gereffi et al. (2005), supply chain process management maturity (organizational capability) by Lockamy and McCormack (2004) and Oliveira et al. (2011), and the suppliers’ performance, technical capability (Fig. 1). In this study we test the framework on the Swedish process industry.

Quadrant 1 (Q1) in Fig. 1 is the category of suppliers with relatively low technical and organizational capabilities, sourced by traditional arm’s-length contracts, often as sub-suppliers at planned shut-downs. They possess neither the organizational capability needed for relational forms of collaboration nor the technical skill to do strategically important core-close maintenance. In quadrant 2, highly mature suppliers can be expected. The low technical capability could indicate entrance in a new market; therefore, the potential to leverage the position into quadrant 4 is very high. Until then, they are governed with market contracts based on price, mostly for corrective maintenance. In quadrant 3, modular contractors making services or products such as spare parts to customer’s specifications could be expected when the suppliers increase their maturity close to the Vision level. In quadrant 4 are found the suppliers with capability to manage deep collaboration and partnerships. They also have the technical skills to perform core-close maintenance, both corrective and preventive, as well as to develop more competitive maintenance processes.

3 Research methodology

We adopted a multiple case study methodology to address the purpose of our research. Four global buying firms and four service suppliers (of which one is global, three regional) participated in the study. The characteristics of the firms are elaborated in the next section. Case study methodology was found appropriate because there is a need to explore a new phenomenon and to build knowledge (Yin 2014). Qualitative case studies have been identified as offering the most interesting research opportunities (Bartunek et al. 2006). Both Weick (1969) and Cronbach (1975) recommend that researchers should “try harder to make interpretations specific to situations”. Learning from a particular case, conditioned by the environmental context, should be considered a strength rather than a weakness. The interaction between a phenomenon and its context is best understood through in-depth case studies (Dubois and Gadde 2002). Even though the number of companies is rather small, this study meets the standard of good credibility, according to the credibility scale for small samples presented by Forza (2002).

The analysis was done in two steps. First, we used the questionnaire from the SCMM model presented by Lockamy and McCormack (2004). The model weights nine variables differently according to their appearance in different constructs in a set of 94 questions, using a five-point Likert scale. The maturity level was then defined by the total score (490) set by the answers of the questionnaire. This maturity model was selected because it had already been tested and validated (Lockamy and McCormack 2004; McCormack et al. 2008; Söderberg and Bengtsson 2010). As a complement, we used the SCPM3 model by Oliveira et al. (2011) to define the levels of maturity, because it is the most updated model and has a strong similarity to the former model. The definition of the different levels is similar and the description of mechanisms and characteristics of each level is somewhat more clarified, although the scores that define each level are slightly different.

The suppliers were each visited for an interview. However, since the maturity models used retain a certain level of subjectivity as they are based on managers’ perceptions (Souza et al. 2015), we recommend that future researchers verify whether data correspond to a firm’s actual practices (McCormack et al. 2009; Souza et al. 2015). The plant management, who in the case of the three local suppliers are the owners of the firms, have scant knowledge about SCM practices, so we went to visit them and discussed the questionnaires together, to give the respondents enough background information about SCM to answer the questions properly. All the respondents agreed with the necessity of this approach.

We used semi-structured interviews to identify what kind of maintenance the four buying firms have outsourced, focusing on maintenance within the production plant (Levery 1998), how they outsourced (both purchased and supplied) the activities, and their future strategy for their maintenance activities. The interviews, conducted with in total 13 maintenance- and purchasing managers in the four steel companies, covered questions concerning strategies for maintenance management and implementations such as supplier selection process, supplier–buyer relationships, strategic contribution of maintenance, internal maintenance organization structure, capability position, attitudes towards outsourcing, and future strategies. In addition, interviews were conducted with supplier 1 on one more occasion to clarify how the local firm fits in with the global parent company’s business model and strategy. This question was asked of the three local suppliers at the same time as the maturity analysis was done. The suppliers’ technical skills were evaluated by the buying firms as well as by the supplier themselves on a scale of low, skillful and highly skillful.

The data analysis was based on written summaries about each case company. After we identified characteristics of maintenance, we initiated a cross-case analysis, looking for similarities and divergences across the cases to find common practices and strategies regarding outsourcing and capability development. All answers as well as analysis done were validated by the respondents at the studied firms (Voss et al. 2002).

3.1 The case companies

The four buying firms (named buying firms 1–4) were chosen because they all have complex manufacturing plants and extensive maintenance but have applied outsourcing to various extents. The participating firms are steel companies producing world-class products used in a variety of areas on the global market (Table 1). These four big steel companies and their supplier base are the foundation for one of Sweden’s biggest industry clusters, and together they represent a majority of Swedish steel industry as well as the foundation of it 150 years ago. Taken together these firms cover a large proportion of the Nordic steel industry.

The participating suppliers (Table 2) were chosen because of their regional connection, and they all supply a variety of industries. All four suppliers serve at least one of the four steel companies participating in the study. These four suppliers cover a majority of maintenance specialists in the region, serving steel, paper and pulp, and complex process industries such as mining firms.

4 Case results

4.1 Buying firms

As shown in Table 1, company sizes differ in both sales and employees. About 10–20 % of the employees are contracted by the maintenance division. The balance between handling maintenance as outsourcing or in-house production is about 50–50 to 40–60, the percentage of outsourcing is a little bit less than in more complex process industries in Sweden such as mining, where the balance is 80–20 % (Maley et al. 2015). Most of the externally services are performed by local or regional suppliers. The trend is to decrease the supplier base for maintenance services, contracting with more capable and mature suppliers as key suppliers. Taken together, our sample of buying firms covers a large proportion of the Nordic steel industry. A summary of the buying firms follows.

-

Buying firm 1 is a global and innovative engineering group with a strong commitment to enhancing customer productivity, profitability, and safety. The company’s operations are concentrated in three core areas: tools and tooling systems for metal cutting, equipment and tools for mining, and products in advanced stainless steels, special alloys, and titanium. Buying firm 1 has approximately 600 employees working with maintenance activities. The mechanical maintenance divisions are centralized for all plants. The companies’ needs for hydraulic and automation services are performed with internal (hierarchical) contracts except for new installations, which are performed externally. All other maintenance services are decentralized, with the responsibility and management inside each plant. The company is using all suppliers except supplier 1, mainly with market contracts (Table 3). They have a few modular contracts with supplier 2 as a complement to their market contracts for corrective maintenance, negotiating for a relational contract involving improvement efforts from the supplier. Supplier 3 is only used for market contracts with some exceptions for spare parts, where they have a modular contract. They later ended their contract with supplier 4 due to the supplier’s inability to develop and sustain its organizational capability. Supplier 4 is now governed by strict captive governance as a subcontractor to a newly contracted international supplier. The company believes there will be many more collaborative and relational contracts in the future as digitization drives analysis and predictability forward, simultaneously increasing the demands for high relative capability positions by the suppliers. The company has some of their core-distant maintenance, such as trucks and overhead cranes, outsourced to highly skillful and mature suppliers competing on an international market.

Table 3 Suppliers and capability positions -

Buying firm 2 is a leading European producer of engineering steel for customers in the bearing, transport, and manufacturing industries. Production comprises primarily bar, tube, ring, and pre-components in low-alloy steels that are often used for demanding applications such as in bearings, powertrains, hydraulic cylinders, and rock drills. The company has a decentralized maintenance organization except for automation and hydraulics, which is performed with internal contracts (hierarchical). Approximately 200 people serve the company with maintenance services. Buying firm 2 only uses suppliers 2 and 3, mainly with market contracts for corrective maintenance. Supplier 2 has had a few modular contracts in recent years. Like supplier 1, they have outsourced core-distant maintenance, such as trucks and overhead cranes, to highly skillful and mature suppliers competing on an international market. Buying firm 2 has the same view as buying firm 1 on the future development of the core-close maintenance services, supported by the possibilities given by future digitization efforts by the industry.

-

Buying firm 3 is a global leader in stainless steel; they create advanced materials that are efficient, long lasting, and recyclable. The company has a rich tradition in metals, and the company has been instrumental in developing the stainless-steel industry into what it is today. The company’s mechanical maintenance is outsourced to the highly skillful and highly mature supplier 1 with partner arrangements and relational governance (Table 3). The contract with supplier 1 has evolved over time as the supplier leveraged their technical skills. The firm has outsourced electrical maintenance, vibration analysis, and services of vital control systems where the company doesn’t have the right competences to more skillful suppliers with a high maturity. The maintenance service is governed with contracts ranging from modular to relational, based on social and technical structures rather than economic, depending on the specifications of the services and the capability position of the supplier. The rest of their maintenance is decentralized, but the company has started a change towards a centralized organization and a decrease in employees from approximately 265 to 165. The firm uses all suppliers except supplier 4 for their outsourced maintenance services. Supplier 2 has both market and modular contracts and supplier 3 holds mainly market contracts for corrective maintenance. They use supplier 3 temporarily for modular contracts of recurrent services and spare parts as needed. They have outsourced core-distant maintenance, such as trucks and overhead cranes, to highly skillful and mature suppliers competing on an international market. They shared the same view as buying firms 1 and 2 on future development of the core-close maintenance services towards relational contracts and partnerships, inspired by the opportunities offered by future digitization efforts by the industry.

-

Buying firm 4 is a Nordic and US-based steel company with a global reach and cost-efficient and flexible production system. The company is a leading producer on the global market for advanced high-strength steels and quenched and tempered steels; standard strip, plate, and tubular products; as well as construction solutions. The company has a centralized maintenance organization and approximately 300 employees within the maintenance organization. They perform services for most of the core-close maintenance such as mechanical, automation, and control systems with internal contracts (hierarchical) or with service agreements from the suppliers of the equipment. External suppliers are mostly used for corrective and time-critical maintenance they don’t have their own resources for. The firm uses supplier 2 for corrective maintenance with market contracts and for more specified maintenance with modular contracts. Suppliers 3 and 4 are contracted mostly for corrective maintenance with market contracts. Core-distant maintenance such as trucks and overhead cranes are outsourced to highly skillful and mature suppliers competing on an international market. Like the others, they have the same view on the future development of the core-close maintenance services.

4.2 Supplier firms

-

Supplier 1 is an established European supplier located all over the world and one of the largest maintenance suppliers in the Nordic countries, active in most areas of maintenance such as facilities, energy, automotive, manufacturing, and complex process industries. It was established in the region when acquiring a local maintenance firm that mainly serves buying firm 3. The firm’s capability position, both technical and organizational capability, is very high (Table 3). The firm mostly uses relational contracts and partnership arrangements involving process development and continuous improvements (CI) for most of their customers. They have more developed partnerships with customers from other industry sectors such as the energy and chemical industries, because they find a higher degree of organizational capability within firms from these industry sectors. After acquiring the local maintenance firm, the supplier tried to implement a partnership based on relational governance but failed due to lack of technical skills and process knowledge of the customers’ production process. After a while, the supplier had increased their skills and process knowledge and could proceed to implement the original business strategy together with the customer. The supplier states that a turning point for success for modular and relation contracts, especially for partnering arrangements, is that both the customer and supplier have the same foundation of capability position, especially the organizational capability (eg, process maturity).

-

Supplier 2 is a well-established, highly skillful, and mature supplier (Table 3) of maintenance services, specialized in serving buying firm 1 with both corrective and preventive maintenance. The supplier also produces both services and spare parts on customer specifications to all four of the buying firms. Supplier 2 does continuous process improvements on a regular basis. The supplier serves international customers with customer-specific products for the energy sector. Supplier 2 is a highly skillful and specialized supplier with good process knowledge of steel plants, in particular the processes of buying firm 1.

-

Supplier 3 is a skillful and low-maturity supplier (Table 3) with a high capacity for rapid and flexible corrective maintenance. Supplier 3 serves all four of the buying firms with market arrangements, mainly for corrective maintenance. Supplier 3 also makes spare parts on customer specifications.

-

Supplier 4 is a skillful and low-maturity supplier with the capacity for corrective maintenance (Table 3). They supply the steel and process industries, as well as the energy and nuclear industries with corrective maintenance based on market contracts. Supplier 4 lost their market contracts and is now acting as a sub-supplier.

-

Buyer firm 1 has a highly skillful and high-maturity internal maintenance organization (Table 3), serving the plant with both corrective and preventive maintenance through hierarchical (internal) contracts, approximately 50–60 % of all performed maintenance. The maturity level is higher than the maturity within the regional suppliers, but not as high as the international supplier 1.

5 Analysis and discussion

Next we will discuss how our empirical findings inform the two research questions of our study. The following analysis and discussion will also provide a basis for validating the proposed conceptual framework presented earlier (Fig. 1).

5.1 Analysis

Our first research question (RQ1) was how the distinction between core-close or core-distant maintenance affects the outsourcing decision. All the buying firms share a consensus about maintenance structure, meaning that maintenance processes inside the production plant must be divided into core-close maintenance or core-distant maintenance due to the impact on production efficiency (high or low strategic impact on overall business performance), and therefore must be managed differently. Processes that directly affect the production line and machinery are considered core-close maintenance, all other processes as core-distant.

The findings show that there is indeed a distinction between different maintenance processes inside the plant, that between core-close and core-distant maintenance. This distinction is of importance for the strategic aspect of the outsourcing decision, when it defines the level of strategic impact of the process, high or low (McIvor 2008). However, this distinction builds upon the process contribution to production efficiency (a distinction not fixed over time) and is not directly connected to the business strategy. That might be one reason, of many others, why corporate management have neglected the strategic importance of maintenance processes. This phenomenon has been identified in the literature (eg, Gupta et al. 2009; Murthy et al. 2002; Pintelon et al. 2006). The results from the study show that maintenance processes are difficult to classify as being of either high or low competitive nature (Cox 1996), and therefore hard to determine whether or how to outsource.

The second research question (RQ2) concerned how capability position affects the governance of the outsourced maintenance activities. The findings show that the governance strategy chosen by the case companies is strongly influenced by the suppliers’ relative capability position. This position depends on a combination of technical capability (eg, skilled individuals, process knowledge, advanced technology, innovative and entrepreneurial approach), and organizational capability (eg, process maturity). The combination sets the prerequisites for the possibilities of different governance options, as displayed in Table 3.

All steel companies in the study combine mainly market governance with arm’s-length contracts based on price for their corrective maintenance using external contracts. As a complement, they all use modular governance with turn-key suppliers based on contracts, emphasizing preventability, capability, flexibility, reliability, and responsiveness, sometimes with a fixed price when mature suppliers are available. Buying firm 3 differs from the others in that they are using relational governance and partnering arrangements with supplier 1 for their core-close maintenance. Buying firm 1 used to govern supplier 4 with a market contract; later, this was changed to a captive governance contract with supplier 4 as a sub-supplier due to the supplier’s relatively low capability position and failure to increase the position (Table 4).

The findings indicate that a high level of only one technical or organizational capability is not enough to build a foundation for modular or relational governance for complex and strategically important maintenance processes. There is a need for high organizational capability (eg, process maturity) and technical capability to handle complex buyer–supplier relationships (Lockamy and McCormack 2004 and Oliveira et al. 2011). This need is confirmed by the transition from market contract to relation-based contract displayed by supplier 1 as their technical capability evolved over time. Furthermore, the study shows that suppliers with strength in only one of these capabilities will most certainly be procured with traditional market contracts. Maturity at least close to the Vision level is needed for modular contracts involving customer-specific information; to the Integration level for relational contracts where cooperation, collaborative behavior, and logistic integration take place. Finally, a maturity at Dynamic level for full partnering arrangements with systematic and integrated horizontal inter-organizational processes, CI efforts, and responsiveness to changing demands is needed (Oliveira et al. 2011; Varoutsa and Scapens 2015; Gereffi et al. 2005). However, notice that it is the lowest capability level of the buyer or the supplier that decides the appropriate governance alternative.

5.2 Discussion

Our findings show that the sourcing framework suggested by McIvor (2008) is valuable for identifying the capability positions of competitors and suppliers, as well as the strategic importance of the outsourced process. However, using the framework alone does not capture the full complexity of the outsourcing decisions made within the case companies. McIvor (2008) does present governance alternatives; he suggests adopting appropriate contractual arrangements to deal with potential opportunism. But his framework does not provide any guidance on how to select governance alternatives based on the supplier firms’ ability to manage highly specific and complex transactions such as partnering arrangements. The governance typology for global value chains by Gereffi et al. (2005) presents a slightly different picture of outsourcing alternatives. They explain the governance options based on the complexity of the transaction rather than the risk of opportunism. Even if the governance typology presented by Gereffi et al. (2005) is not introduced as a decision framework, it illustrates well how the governance mechanisms and needs increase as the customer-supplier relationship becomes more complex. Our study confirms that and highlights the need for governance allowing complex interfirm coordination, especially for complex core-close maintenance within partnership arrangements. However, like the framework from McIvor (2008), it doesn’t take the suppliers’ ability to conduct the relationship into account. Thus, there is a need for a third perspective on the outsourcing issue.

In relationship to the Supply Chain Process Management Maturity model by Lockamy and McCormack (2004) and Oliveira et al. (2011), a third perspective emerges: organizational capability. This kind of capability defines the supplier’s ability to collaborate and interact with the outsourcing firm and manage those complex transaction characteristics identified by Gereffi et al. (2005). Our study confirms the conclusions reached by Varoutsa and Scapens (2015) that governance structure evolves a more trustworthy and technical structure as the supply chain matures and transaction complexity increases (Gereffi et al. 2005). We agree with Lockamy and McCormack (2004) and Oliveira et al. (2011) when they discuss the necessity to reach a high maturity level to be able to manage deep intra-organizational collaboration and interactions with partners. This is especially interesting when combined with the frameworks of Gereffi et al. (2005), McIvor (2008), and the results from Varoutsa and Scapens (2015).

Summarizing, our study suggests that outsourcing decisions are far more complex and difficult than shown in existing frameworks. McIvor (2008) highlights the capability position but excludes organizational capability. Gereffi et al. (2005) stress the transaction complexity and the ability to manage information sharing and collaboration, but do not directly address organizational capability or process maturity. Varoutsa and Scapens link the level of supply chain maturity to governance evolvement, addressing the supply chain in a broader sense. The SCMM model by Lockamy and McCormack (2004) is also relevant, since it captures the temporal evolution of the outsourcing relationships as described in the case companies. Together these frameworks build a foundation for outsourcing decisions.

6 Conclusions

Our findings highlight the importance of identifying the outsourced maintenance process contribution to production efficiency, and thereby categorizing the maintenance as core-close or core-distant. The results from the study show that the capability position of the supplier, specifically the mix of technical and organizational capability, affects and influences the choice of governance option with maintenance outsourcing, as well as the relationship with the supplier.

Our study makes at least two theoretical contributions. Firstly, the study contributes to outsourcing literature confirming the outsourcing strategy framework by McIvor (2008) as a useful tool even for analyzing support processes such as maintenance. Secondly, the study contributes to SCM literature by emphasizing that when a supply chain matures, the supply chain reconstructs and SCM relies more on collaboration and trust than formal contracts and control mechanisms (Ballou et al. 2000 and Varoutsa and Scapens 2015). Maintenance is no exception. We furthermore confirmed the claims by Gereffi et al. (2005) and Varoutsa and Scapens (2015) that governance changes as the value chain matures or evolves to be more complex. We have extended the validity of these frameworks by testing them in a new and specific context.

Looking at implications, we believe the findings can help managers to better understand the important of the maintenance distinctions (core-close or core-distant) for the outsourcing decision, as it affects the production efficiency and thereby the firm’s overall business strategy. It could also help managers to be familiar with the characteristics of their firm’s capability position and leverage the understanding of how capability position influences the governance decision. Furthermore, the framework presented here could provide guidelines for choosing the right supplier (Ireland et al. 2002 and Dekker 2004) by showing what capability position the supplier needs for each different level of transaction complexity expressed by the governance typology defined by Gereffi et al. (2005), and thereby designing appropriate governance mechanisms (Williamson 1999; Gereffi et al. 2005; Meer-Kooistra and Scapens 2008; McIvor 2008). We support Varoutsa and Scapens (2015) in their opinion that a firm is unlikely to be able to move from arm’s-length relationships to collaborative relationships in a single step. Governance mechanisms must evolve; they cannot be designed and put in place. Furthermore, personal and technical skills are also needed for a deeper relationship, and they must evolve too.

7 Limitations and further research

There are several limitations of our study. One limitation is the process-industry focus, which might limit the generalizability of the findings even though outsourcing and governance issues are relevant in other industries. Further research is required to obtain an in-depth understanding of the outsourcing decision-making process in relation to maintenance and governance. A key issue here is to understand the distinction between core-close and core-distant maintenance, as well as how the capability position affects the design of governance mechanisms and structures. It would thus be useful to explore in depth governance structures in existing partnerships between buyer and suppliers in a variety of industries.

The new era of digitization and the Internet of Things (IoT) increases the strategic importance of those decisions. Managers have new opportunities to diagnose, predict, solve, and maintain production. Thus, the knowledge required to manage maintenance activities has become more challenging, resulting in pressure on manufacturers to outsource maintenance to specialized suppliers. Therefore, it would be valuable to do research on the impact of IoT on the outsourcing of maintenance requirements.

References

Arnold U (2000) New dimensions of outsourcing: a combination of transaction cost economics and the core competencies concept. Eur J Purch Supply Manag 6(1):23–29

Aron R, Singh J (2005) Getting offshoring right. Harward Bus Rev 83(12):135–143

Ballou HR, Gilbert MS, Mukherjee A (2000) New managerial challenges from supply chain opportunities. Ind Mark Manag 29(1):7–18

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17(1):91–120

Barthèlemy J, Quèlin BV (2006) Complexity of outsourcing contracts and ex post transaction costs: an empirical investigation. J Manag Stud 43(8):1775–1797

Bartunek J, Rynes S, Ireland R (2006) What makes management research interesting and why does it matter? Acad Manag J 49(1):9–15

Bengtsson L (2008) Outsourcing manufacturing and its effect on engineering firm performance. Int J Technol Manag 44(3/4):373–390

Bengtsson L, von Haartman R, Dabhilkar M (2009) Low-cost vs. innovation: contrasting outsourcing and integration strategies in manufacturing. Creat Innov Manag 18(1):35–47

Bettis R, Bradley S, Hamel G (1992) Outsourcing and industrial decline. Acad Manag 6(1):7–22

Büner R, Tuschke A (1997) Outsourcing. Die Bitriebswirtschaft 57(1):20–30

Caglio A, Ditillo A (2008) A review and discussion of management control in inter-firm relationships: achievements and future directions. Acc Organ Soc 33:865–898, Oct-Nov,7-8

Caglio A, Ditillo A (2012) Opening the black box of management accounting information exchanges in buyer–supplier relationships. Manag Account Res 23(2):61–78

Cox A (1996) Towards an entripreneurial and contractual theory of the firm. Eur J Purch Supply Manag 2(1):57–70

Cronbach L (1975) Beyond the two disciplines of scientific psychology. Am Psychol 30(2):116–127

Datta PP, Roy R (2013) Incentive issues in performance-based outsourcing contracts in UK defence industry: a simulation study. Prod Plan Control 24:359–374, april-may,4-5

Dekker HC (2004) Control of inter-organizational relationships: evidence on appropriation concerns and coordination requirements. Acc Organ Soc 29:27–49, January,1

Dekker HC (2008) Partner selection and governance design in interfirm relationships. Acc Organ Soc 33:915–941, Oct-Nov,7-8

Dubois A, Gadde L-E (2002) Systematic combining: an abductive approach to case research. J Bus Res 55(7):553–560

Forza C (2002) Survey research in operations management: a process-based perspective. Int J Oper Prod Manag 22(2):152–194

Gereffi G, Humphrey J, Sturgeon T (2005) The governance of global value chains. Rev Int Polit Econ 12(1):78–104

Ghayebloo S, Shahanaghi K (2010) Determining maintenance system requirements by viewpoint of reliability and lean. J Qual Maint Eng 16(1):89–106

Gilley KM, Rasheed A (2000) Making more by doing less: an analysis of outsourcing and its effects on firm performance. J Manag 26(4):763–790

Gupta S, Woodside A, Dubelaar C, Bradmoore D (2009) Diffusing knowledge-based core competencies for leveraging innovation strategies: modeling outsourcing to knowledge process organization (KPOs) in pharmazeptcal networks. Ind Mark Manag 38(2):219–227

Hätönen J, Eriksson T (2009) 30 + years of research and practices of outsourcing-exploring the past and anticipating the future. J Int Manag 15(2):142–155

Ireland RD, Hitt MA, Vaidyanath D (2002) Alliace management as a source of competetive advatage. J Manag 28(3):413–446

Ishizaka A, Blakiston R (2012) The 18C’s model for a successfullong-term outsourcing arrangement. Ind Mark Manag 41(7):1071–1080

Johnsen T, Johnsen R, Lamming R (2008) Supply relationship evaluation: the relationship assesment process (RAP) and beyond. Eur Manag J 26(4):274–287

Kakabadse N, Kakabadse A (2000) Critical review- outsourcing: a paradigm shift. J Manag Dev 19(8):670–728

Lahti M, Shamsuzzha A, Helo P (2009) Developing a maturity model for supply chain management. Int J Logistics Syst Manag 5(6):654–678

Levery M (1998) Outsourcing maintenance - a question of strategy. Eng Manag J 8:34–40, February,1

Lockamy A, McCormack K (2004) The developement of supply chain management process maturity model using the concepts of business process orientation. Supply Chain Manag : Int J 9(4):272–278

Lonsdale C (1999) Effectively managing vertical supply relaitionships: a risk management model for outsourcing. Supply Chain Manag : Int J 4(4):176–183

Madhok A (2002) Reassessing the fundamental and beyond: Ronald Coase, the transaction cost and resource-based theories of the firm and institutional structure of production. Strateg Manag J 23(6):535–550

Maley J, Kowalkowski C, Brege S, Biggeman S (2015) Outsourcing maintenance in complex process industries - managing firm capabilities in lock-in effect. Asia Pac J Market Logistics 27(5):801–825

McCormack K, Ladeira MB, Valderes de Oliviera MP (2008) Supply chain maturity and performance in Brazil. Supply Chain Manag : Int J 13(4):272–282

McCormack K, Willems J, van den Bergh J, Deschoolmeester D, Willaert P, Štemberger MI, Škrinjar R, Trkman P, Ladeira MB, de Oliveira MPV, Vuksic VB, Vlahovic N (2009) A global investigation of key turning points in business process maturity. Bus Process Manag J 15(5):792–815

McHugh M, Humphreys P, McIvor R (2003) Buyer–supplier relationships and organizational health. J Supply Chain Manag 39(2):15–25

McIvor R (2000) A practical framework for understanding the outsourcing process. Supply Chain Manag : Int J 5(1):22–36

McIvor R (2005) The outsourcing process. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

McIvor R (2008) What is the right outsourcing strategy for your process. Eur Manag J 26(1):24–34

McIvor R (2009) How the transaction cost and resource-based theories of the firm inform outsourcing evaluation. J Oper Manag 27(1):45–63

Meer-Kooistra J v d, Scapens RW (2008) The governance of lateral relations between and within organisations. Manag Account Res 19(4):365–384

Murthy D, Atrens A, Eccleston J (2002) Strategic maintenance management. J Qual Maint Manag 8(4):287–305

Oliviera MPV, Ladeira M, McCormack K (2011) The supply chain process management mautity model-SCPM3. Supply Chain Manag - Pathways Res Pract XX(XX):201–218

Pintelon L, Pinjala SK, Vereecke A (2006) Evaluating the effectiveness of maintenance strategies. J Qual Maint Eng 12(1):7–20

Prahalad C, Hamel G (1990) The core competence of the corporation. Harward Business Review. Issue may-jun

Quèlin B, Duhamel F (2003) Bringing together strategic outsourcing and corporate strategy: outsourcing motives and risks. Eur Manag J 21(5):647–661

Quinn JB (2000) Outsourcing innovation: the new engine of growth. Sloan Manag Rev 41(summer, 4):13–28

Quinn JB, Hilmer FG (1994) Strategic outsourcing. Sloan Manag Rev 35(Summer,4):43–55

Sanchís-Pedregosa C, Palacín-Sánchez M-J, González-Zamora M-d-M (2014) Exploring the financial impact of outsourcing services strategy on manufacturing firms. Oper Manag Res 7(3):77–85

Söderberg L, Bengtsson L (2010) Supply chain management maturity and performance in SMEs. Oper Manag Res 3(1):90–97

Souza RP, Guerreiro R, Oliviera MPV (2015) Relationship between the maturity of supply chain process management and the organisational life cycle. Bus Process Manag J 21(3):466–481

Stevensson M, Spring M (2009) Supply chain flexibility: an inter-firm empirical study. Int J Oper Prod Manag 29(9):946–971

Varadarajan R (2009) Outsourcing: think more expansively. J Bus Res 62(11):1165–1172

Varoutsa E, Scapens RW (2015) The governance of inter-organisational relationships during different supply chain maturity phases. Ind Mark Manag 46(April):68–82

Vitasek K, Manrodt K (2012) Vested outsourcing: a flexible framework for collaborative outsourcing. Strategic Outsourcing: Int J Vol. 5(No1):4–14

Voss C, Tsikriktsis N, Frohlich M (2002) Case research in operation management. Int J Oper Prod Manag 22(2):116–137

Wathne KH, Heide JB (2004) Relationship governance in a supply chain network. J Mark 68(No.1):73–89

Weick K (1969) The social psychology of organization, 1st edn. Addison-Wesley, Reading

Williamson OE (1985) The economics institutions of capitalism. The Free Press, McMillan Inc., New York

Williamson OE (1991) Comparative economic organization: the analysis of discreat structual alternatives. Adm Sci Q 36(2):269–296

Williamson OE (1998) The institution of governance. Am Econ Rev 8(2):75–79, May,2

Williamsson O (1999) Strategic research: governance and competence perspectives. Strateg Manag J 20(12):1087–1108

Yin RK (2014) Case study research: design and methods, 5th edn. Sage Publications, London

Zaheer A, Venkatraman N (1995) Relational governance as a interorganizational strategy: an empirical test of the role of trust in economic exchange. Strateg Manag J 16(5):373–392

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Söderberg, L., Bengtsson, L. & Kaulio, M. A model for outsourcing and governing of maintenance within the process industry. Oper Manag Res 10, 20–32 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-016-0121-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-016-0121-0