Abstract

Radiation therapy for broncho-pulmonary malignancies can lead to fistula formation between the digestive and respiratory tracts. Treatment options have been largely palliative in nature. Here, we report a combined pneumonectomy and esophagectomy, followed by staged retrosternal gastric pull-up esophageal reconstruction, for treatment of a broncho-esophageal fistula with good functional outcomes following reconstruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fistula formation between the digestive and respiratory tracts in the setting of broncho-pulmonary malignancy is a rare but often devastating complication [1, 2]. While various palliative procedures have been described, quality of life is usually severely compromised and life expectancy is measured in months [3, 4]. Herein, we describe a case of radiation-associated broncho-esophageal fistula treated with a two-stage procedure, comprising a combined pneumonectomy and esophagectomy, followed by esophageal reconstruction with a gastric conduit.

Case report

A 70-year-old male, with a 40 pack-year history of smoking, presented with worsening dyspnea. He underwent bronchoscopy with findings of a partially obstructing endobronchial tumor of the left main stem bronchus. Pathology revealed a mucinous adenocarcinoma. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) demonstrated a single lesion of the left main bronchus with no evidence of distant metastases (cT2NXMX). Surgical resection was advised by the multidisciplinary tumor board; however, the patient refused surgery due to concerns regarding an extended hospitalization during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Despite repeated, detailed explanations of the dangers of forgoing surgery, the patient, together with his close family, was steadfast in refusal of surgery. He then was treated with trans-bronchial laser ablation, followed by a total of 40 Gy of external beam radiation over 3 weeks, and an additional 15-Gy transbronchial brachytherapy session at the final visit. PET-CT, 2 months post-treatment, revealed no areas of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake suspicious for neoplasia.

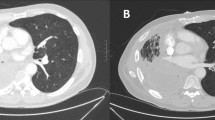

Seven months following treatment completion, due to persistent cough, he underwent extensive work up and a 3-cm broncho-esophageal fistula was observed at the proximal left main stem bronchus extending to the esophagus at 28 cm from the incisors. Fistula formation in this patient may have been caused by various mechanisms. However, due to the excellent response to treatment, the most likely explanation was tissue damage due to radiation treatment. The patient was transferred to our center and a bronchial, covered, metal stent was deployed to cover the fistula and a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) was inserted for enteral access (Figs. 1 and 2).

Due to recurrent episodes of pneumonia, despite bronchial stenting, a decision was made to attempt lung preservation and surgical repair with fistula resection. Prior to surgery, the patient was referred to our surgical geriatrician for pre-surgical evaluation. An individualized prehabilitation plan, including dietary supplementation and physical therapy, was advised.

Surgery was performed through a left posterolateral thoracotomy and a wide area of radiation-induced necrosis of the left main stem bronchus extending into the secondary carina was observed. These findings precluded lung preservation and a left pneumonectomy was carried out. Following fistula resection, a 4-cm-wide esophageal opening was noted with a severe inflammatory response surrounding the adjacent tissue. Due to the unacceptably high risk of leak with either a primary repair or esophageal stenting, esophagectomy was carried out with trans-thoracic closure of the esophageal hiatus and an end esophagostomy was brought out in the left neck. Pathological examination did not find evidence of carcinoma and was notable only for pneumonia and severe inflammation.

Beside evacuation of a chest wall hematoma on post-operative day 3, and transient left vocal cord paresis, the patient recovered extremely well and was discharged home on post-operative day 14. Five months later, a retrosternal gastric pull-up was done for reconstruction of the upper gastro-intestinal (GI) tract. A tubularized gastric pedicle, based on the right gastroepiploic arcade, was constructed, excluding the portion containing the gastrostomy. The gastric conduit was then brought to the left neck through the retrosternal space, following partial manubrium and clavicular head resection. End-to-side esophago-gastric anastomosis was fashioned using a circular stapler (CDH 25, Ethicon ®). He recovered well and was discharged home on post-operative day 14, tolerating liquid diet following a benign upper GI barium follow-through study.

By four weeks post-operative, the patient was completely weaned from jejunostomy feeding while meeting all caloric goals. The patient was seen in the clinic 4 months later having recovered well from surgery.

Comment

The anatomical proximity of the esophagus and left main bronchus, coupled with the paucity of connective tissue between the structures, predisposes the structures to fistula formation. Aquired broncho-esophageal fistula is a rare but often devastating pathology, with numerous causes. In a large cohort of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, receiving split-course palliative thoracic radiotherapy (PTR), 0.2% were found to develop broncho-esophageal fistula [5]. In the setting of malignancy, fistula may be caused by a number of mechanisms, including direct tumor invasion, tumor necrosis following treatment, direct effects of radiation, and malignant lymph node necrosis [3].

Clinical suspicion is usually raised due to the appearance of respiratory symptoms ranging from persistent cough to repeated episodes of aspiration pneumonia. Imaging studies such as upper GI fluoroscopy or computed tomography with oral contrast will establish the diagnosis, with confirmation from endoscopic evaluation consisting of esophagogastroduodenoscopy and/or bronchoscopy [1].

In most reported cases, treatment is palliative and revolves around stenting of either the esophagus, bronchus, or both. These techniques, which may offer temporary relief of symptoms, are susceptible to severe complications including stent migration, perforation, and pressure necrosis of surrounding tissues [1, 3]. Fistula closure using endoscopic clipping, fibrin glue, or Amplatzer devices has been described as well [3, 6]. Although acceptable, these procedures are usually short-lived and only suitable for small fistulae.

Conversely, surgical interventions are rarely performed, possibly due to the extensive morbidity and frailty of the majority of patients suffering from malignant broncho-esophageal fistula. Patient selection is imperative, and a multidisciplinary team evaluation, led by thoracic and foregut surgeons, as well as prehabilitation with the help of a surgical geriatrician [7], is highly advised. Wide exposure of the fistula following pulmonary resection is needed in order to allow visualization of the esophagus and to define the fistula resection margins. Although combined right sleeve pneumonectomy and esophagectomy have been described elsewhere [8], this surgery was palliative in nature and resulted in a resection with known residual tumor remaining. We elected to perform a definitive surgery, in order to reduce the potential complications of an additional anastomosis, as well as to ensure an optimal oncologic outcome. Although a one-step procedure is theoretically possible, we chose a delayed reconstruction of the alimentary tract using the retrosternal route in order to avoid possible contamination of the pneumonectomy space in an already-high-risk patient.

Conclusion

Malignant broncho-esophageal fistula is a rare diagnosis which usually is treated with palliative measures. In fit patients with good oncological status, more radical solutions may provide improved survival and quality of life.

References

Hürtgen M, Herber SCA. Treatment of malignant tracheoesophageal fistula. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24:117–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.09.006.

Balazs A, Kupcsulik PK, Galambos Z. Esophagorespiratory fistulas of tumorous origin. Non-operative management of 264 cases in a 20-year period. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:1103–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.06.025.

Shamji FM, Inculet R. Management of malignant tracheoesophageal fistula. Thorac Surg Clin. 2018;28:393–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thorsurg.2018.04.007.

Hu Y, Zhao Y-F, Chen L-Q, et al. Comparative study of different treatments for malignant tracheoesophageal/bronchoesophageal fistulae. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:526–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00950.x.

Reinfuss M, Mucha-Małecka A, Walasek T, et al. Palliative thoracic radiotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. An analysis of 1250 patients. Palliation of symptoms, tolerance and toxicity. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:344–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.06.019.

Zhou C, Hu Y, Xiao Y, Yin W. Current treatment of tracheoesophageal fistula. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2017;11:173–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753465816687518.

Cooper L, Levy Y, Nissenholtz A, Bugaevsky Y, Kashtan H, Beloosesky Y. Evaluation of the elderly patient with cancer. Harefuah. 2020;159:678–82.

Watanabe I, Takamochi K, Oh S, Suzuki K. Salvage surgery for lung cancer with tracheo-oesophageal fistula during concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2019;29:641–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivz137.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception of the study as well as the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee of Rabin Medical Center in view of the retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care.

Informed consent

Verbal informed consent was obtained prior to the beginning of this study, including consent to publish.

Statement of human and animal rights

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. No animals were used in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Slomowitz, E., Tverskov, V. & Wiesel, O. Combined pneumonectomy and esophagectomy for radiation-associated broncho-esophageal fistula. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 38, 648–650 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12055-022-01381-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12055-022-01381-8