Abstract

Background

Multiple studies demonstrate that fever/elevated temperature is associated with poor outcomes in patients with vascular brain injury; however, there are no conclusive studies that demonstrate that fever prevention/controlled normothermia is associated with better outcomes. The primary objective of the INTREPID (Impact of Fever Prevention in Brain-Injured Patients) trial is to test the hypothesis that fever prevention is superior to standard temperature management in patients with acute vascular brain injury.

Methods

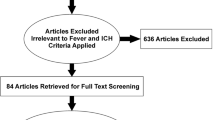

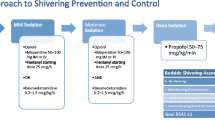

INTREPID is a prospective randomized open blinded endpoint study of fever prevention versus usual care in patients with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. The fever prevention intervention utilizes the Arctic Sun System and will be compared to standard care patients in whom fever may spontaneously develop. Ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage or subarachnoid hemorrhage patients will be included within disease-specific time-windows. Both awake and sedated patients will be included, and treatment is initiated immediately upon enrollment. Eligible patients are expected to require intensive care for at least 72 h post-injury, will not be deemed unlikely to survive without severe disability, and will be treated for up to 14 days, or until deemed ready for discharge from the ICU, whichever comes first. Fifty sites in the USA and worldwide will participate, with a target enrollment of 1176 patients (1000 evaluable). The target temperature is 37.0 °C. The primary efficacy outcome is the total fever burden by °C-h, defined as the area under the temperature curve above 37.9 °C. The primary secondary outcome, on which the sample size is based, is the modified Rankin Scale Score at 3 months. All efficacy analyses including the primary and key secondary endpoints will be primarily based on an intention-to-treat population. Analysis of the as-treated and per protocol populations will also be performed on the primary and key secondary endpoints as sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

The INTREPID trial will provide the first results of the impact of a pivotal fever prevention intervention in patients with acute stroke (www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT02996266; registered prospectively 05DEC2016).

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- ASPECTS:

-

Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score

- CEC:

-

Clinical Events Committee

- DMC:

-

Data Monitoring Committee

- EC:

-

Ethics Committee

- FDA:

-

United States Food and Drug Administration

- F/U:

-

Follow-up

- ICDSC:

-

Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist

- ICF:

-

Informed Consent Form

- ICH:

-

Intracerebral hemorrhage

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- IS:

-

Ischemic stroke

- LAR:

-

Legally Authorize Representative

- MAE:

-

Major adverse event

- mRS:

-

Modified Rankin Scale

- NIHSS:

-

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- MoCA:

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- PP:

-

Per protocol

- SAE:

-

Serious adverse event

- SAH:

-

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- SAP:

-

Statistical analysis plan

- SCA:

-

Sudden cardiac arrest

- SOC:

-

Standard of care

- TBI:

-

Traumatic brain injury

- TH:

-

Therapeutic hypothermia

- TTM:

-

Targeted temperature management

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- WFNS:

-

World Federation of Neurological Societies grading system for subarachnoid hemorrhage

References

Arpino PA, Greer DM. Practical pharmacologic aspects of therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(1):102–11.

Greer DM, Rosenthal ES, Wu O. Neuroprognostication of hypoxic-ischaemic coma in the therapeutic hypothermia era. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(4):190–203.

Rincon F, Rossenwasser RH, Dumont A. The epidemiology of admissions of nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage in the United States. Neurosurgery. 2013;73(2):217–22.

Rincon F, Mayer SA. The epidemiology of intracerebral hemorrhage in the United States from 1979 to 2008. Neurocrit Care. 2013;19(1):95–102.

Marion DW. Controlled normothermia in neurologic intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(2 Suppl):S43–5.

Kammersgaard LP, Jorgensen HS, Rungby JA, et al. Admission body temperature predicts long-term mortality after acute stroke: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke. 2002;33(7):1759–62.

Reith J, Jorgensen HS, Pedersen PM, et al. Body temperature in acute stroke: relation to stroke severity, infarct size, mortality, and outcome. Lancet. 1996;347(8999):422–5.

Prasad K, Krishnan PR. Fever is associated with doubling of odds of short-term mortality in ischemic stroke: an updated meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;122(6):404–8.

Wartenberg KE, Schmidt JM, Claassen J, et al. Impact of medical complications on outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3):617–23.

Schwarz S, Hafner K, Aschoff A, Schwab S. Incidence and prognostic significance of fever following intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2000;54(2):354–61.

Leira R, Davalos A, Silva Y, et al. Early neurologic deterioration in intracerebral hemorrhage: predictors and associated factors. Neurology. 2004;63(3):461–7.

Greer DM, Funk SE, Reaven NL, Ouzounelli M, Uman GC. Impact of fever on outcome in patients with stroke and neurologic injury: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Stroke. 2008;39(11):3029–35.

Broessner G, Beer R, Lackner P, et al. Prophylactic, endovascularly based, long-term normothermia in ICU patients with severe cerebrovascular disease: bicenter prospective, Randomized Trial. Stroke. 2009;40:e657–65.

Fischer M, Lackner P, Beer R, Helbok R, et al. Cooling activity is associated with neurological outcome in patients with severe cerebrovascular disease undergoing endovascular temperature control. Neurocrit Care. 2015;23(2):205–9.

Badjatia N, Fernandez L, Schmidt JM, Lee K, et al. Impact of induced normothermia on outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case–control study. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(4):696–700.

Mayer SA, Kowalski RG, Presciutti M, Ostapkovich ND, et al. Clinical trial of a novel surface cooling system for fever control in neurocritical care patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(12):2508–15.

Bohman LE, Levine JM. Fever and therapeutic normothermia in severe brain injury: an update. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014;20(2):182–8.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the study sponsor, C. R. Bard.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from Becton Dickinson (Franlin Lakes, NJ).

Conflict of interestDr. Greer has received research support to his institution as PI for the INTREPID study from Becton Dickenson. Ms. Ritter is an employee of Becton Dickenson, the study sponsor. Dr. Helbok has received travel grants and lecture fees from Bard Medical, Zoll Medical, Fresenius Kabi, and Integra Life Sciences outside of the submitted work. Dr. Badjatia has received research funding from Becton Dickinson, and has received research funding from Zoll Inc, the Department of Defense and Maryland Industrial Partnerships. Dr. Ko has nothing to disclose. Ms. Guanci has nothing to disclose. Dr. Sheth has received research support to his institution as co-PI for the INTEPID study from Becton Dickinson. He has consulted for Zoll Medical as DSMB chair for another study. He reports receiving funding from Ncontrol for ad board consulting, and from Alva Equity.

Ethical Approval/Informed ConsentThe study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Date 01/2017). Informed consent was obtained from the patient or LAR prior to inclusion. The inclusion/exclusion criteria are included in detail in the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study concept and design were given by DG, KS and JR. Data acquisition and analysis not applicable (protocol manuscript). DG prepared the first draft of the manuscript. Interpretation of the data not applicable (protocol manuscript). All authors provided critical feedback of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Clinical trial registration

The study is now on version 7.0, last updated March 2020. Recruitment began in March 2017, and recruitment is estimated to be completed by April 2022.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greer, D.M., Ritter, J., Helbok, R. et al. Impact of Fever Prevention in Brain-Injured Patients (INTREPID): Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurocrit Care 35, 577–589 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-021-01208-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-021-01208-1