Abstract

The “facie sympathique” is a vital sign first described by Etienne Martin in 1899 referring to unilateral miosis, with or without ptosis, at the opposite side from the knot in hanging. This mark is scarcely reported in legal medicine textbooks and scientific papers. Moreover, when cited, it is referred to differently from its original meaning, both as unilateral contraction (miosis) and dilatation (mydriasis) of the pupil depending on the antemortem firmness of the ligature’s neck pressure in hanging with little attention to ptosis. Due to the sympathetic nervous pathway supplying the eye, the review of this ocular sign in hanging supports the importance of revitalizing the “facie sympathique” in research on lesion vitality in mechanical asphyxia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hanging is the most frequent form of mechanical asphyxia in suicide in most countries [1, 2]. However, the judicial authority does not frequently pursue investigations by forensic autopsy and toxicological examination in hanging cases. In Italy, for instance, the magistrate usually limits the forensic investigation to medico-legal doctor participation at the crime scene and external examination. Hence, the medico-legal contribution does not reduce the risk of a misclassified death cause and manner. Forensic researchers have long been engaged in distinguishing antemortem from postmortem hanging biomarkers through the analysis of skin wounds at the ligature neck mark [3], fractures of the neck structures [4,5,6], injuries of the soft tissue [7], and the presence of intimal layer tears in the carotid artery (Amussat’s sign) and hemorrhages on the anterior surface of the intervertebral lumbar disc (Simon’s bleedings) [8,9,10].

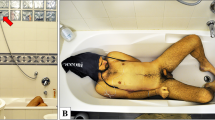

In 1899, Etienne Martin (1871–1949) first described the presence of unilateral miosis with partial superior eyelid closure (ptosis) on the opposite side of the knot in two individuals who died due to hanging (Fig. 1), which he named the “facie sympathique” as it resembled a patient’s face after sympathectomy. However, disagreement about the interpretation of the “facie sympathique” as an antemortem ocular mark of neck compression arose soon after its first description (1899) [11, 12].

Photograph of the “facie sympathique” in an individual who died due to hanging. Etienne M. “Le facies sympathique des pendus.” Archives de l’anthropologie criminelle (vol. 14; 1899, Page 178), Musée Criminocorpus consulted on Nov. 9, 2022, https://criminocorpus.org/en/ref/114/9565/

This paper offers a historical and narrative medico-legal contribution to better understand whether the “facie sympathique” finding should be re-evaluated by forensic pathologists as a marker of vital compression of the neck, a key forensic analysis topic in cases of mechanical asphyxia caused by hanging.

Historical background

An important initial aspect is a revision of the studies on hanging conducted by Etienne Martin (1871–1949) and Nicolae Minovici (Bucarest, 1868–1941) at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Etienne Martin, who followed A. Lacassagne as the chair of forensic medicine in 1913 at the Médecine Légale Institute of the Faculté de Médecine de l’Université de Lyon, reported two cases of hanging where the loop of the rope was deeper at the left side of the neck (first case) and at the right side (second case) in an article titled “Le facies sympathique des pendus” (1899) [11]. In the first case, he observed a concomitant presence of miosis (5 mm on the left vs. 7 mm on the right) and ptosis in the left eye. He also noted tearing of the intimal layer of the left carotid artery (Amussat’s sign) and hemorrhage of the ipsilateral superior sympathetic ganglion at the noose level. In the second case, he noted miosis at the right pupil, facial congestion, tongue placement between the teeth, and hemorrhagic petechiae at the legs.

In both cases, in the opinion of Etienne Martin, the facial findings resembled those observed by the surgeon M. Jaboulay in patients sympathectomized for exophthalmos due to goiter [13]. Thus, based on surgical knowledge, Etienne Martin suggested that compression and/or stimulation by stretching of the cervical sympathetic trunk is responsible for pupillary inequality in hanging.

It could be argued that the close cooperation between French and Romanian researchers was the reason why in 1904, Nicolae Minovici (of Bucarest) visited the laboratory of Etienne Martin at the Médecine Légale Institute of the l’Université de Lyon to “faire la connaisence” [14]. In the book “Studiu asupra spânzurării” [15], translated into French in 1905, Nicolae Minovici reported his experience on 51 cases, considering his results as “absolutament contraries” to those of Etienne Martin; it was assumed that the higher-strength neck compression was at the opposite side of the knot (loop) [14]. Although Nicolae Minovici did not provide any alternative pathogenic explanation to Etienne Martin’s thesis, he stated that pupillary and eyelid inequality represents an unpredictable postmortem facial sign that can be associated with individuals who died from disease rather than from hanging. However, some of the data collected by Nicolae Minovici (Table 1) do not seem to be “absolutament contraries” from Etienne Martin’s experience. By reviewing the information in Table 1, Minovici described miosis at the side of the loop in 5 of 51 hanging cases (case n.19 at left, n.15 at right; n.6, 7, 8 loop anteriorly) and ptosis at the side of the loop in 1 of 51 cases (case n.6 on the right side). Moreover, Minovici reported pupilar “inégales” on the same side of the loop in 7 of 51 cases (n.9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 20).

Medico-legal narrative review

Many legal medicine textbooks and scientific papers have been published since the beginning of the twentieth century. However, assessments of this peculiar facial finding have rarely been conducted in the international medico-legal literature [16]. Nevertheless, the presence of anisocoria in hanging is cited as a “significant” central nervous system sign [17] or as a “specific” sign [18]. Payne-James et al. reported that anisocoria, although rarely observed in hanging, “may be caused by pressure of the strangulation device on the cervical sympathetic nerve” [19]. Interestingly, when these ocular signs are mentioned, they are considered vital signs and reported differently from Etienne Martin’s original experience regarding the presence of miosis, the involvement of the upper eyelid (ptosis), and the site of the neck at which the rope’s section (knot or loop) is believed to be responsible for the pressure on cervical sympathetic nerves. Several authors described the “facie sympathique” as mydriasis and an open eyelid at the side of the knot instead of miosis and partial eyelid closure (ptosis) at the side of the loop, as described by Etienne Martin [20,21,22,23]. Polson et al. described the presence of anisocoria on the side of the ligature knot [24] without specifying the eye signs (miosis or mydriasis). In the Forensic Atlas edited by Weimann and Prokop [25], the presence of ptosis is described in asphyxia deaths related to strangulation while eyelids are not visible in the pictures regarding hanging. The pupil status is not shown in both cases. Finally, most of the forensic case reports on hanging retrieved by searching the PubMed database up to September 2022 have the victim’s eyes hidden by a black strip for privacy.

The differences in “facie sympathique” reporting in hanging among forensic texts might have an historical explanation. Undoubtedly, the interruption of the cervical sympathetic nervous system supplying the eye (Fig. 2) with unilateral miosis together with ptosis dates to 1852 in the report of Claude Bernard [26], a researcher at the Faculté de Médecine de l’Université de Lyon (the same institution as Etienne Martin). However, evidence of ocular inequality due to sympathetic involvement was previously identified in dogs by Pourfour du Petit (1775), who gave his name to the syndrome characterized by unilateral mydriasis (not miosis), eyelid retraction (not ptosis), and sometimes hyperhidrosis [27]. These ocular signs (mydriasis and eyelid retraction) have been considered by recent researchers [28] due to an interesting lesion (not an interruption) observed in the cervical sympathetic nervous system and may precede Claude Bernard’s disease.

Anatomy of the sympathetic nervous system supplying the eye. Gray, Henry. Anatomy of the Human Body. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1918; Fig. 840, Sympathetic connections of the ciliary and superior cervical ganglia. Bartleby.com, 2000, consulted on Nov. 9, 2022. www.bartleby.com/107/

Thus, there are two ways that involvement of the cervical sympathetic nervous system might produce the “facie sympathique” in hanging: nerve interruption at the site of the ligature’s strongest compression, causing miosis, or nerve excitation by stretching (not interruption), which might occur in the area close to the point of the knot, causing mydriasis.

Medico-legal perspectives

The idea of a relationship between the “facie sympathique” (miosis and ptosis) and cervical sympathetic pathway damage in hanging does not seem to be confined to the beginning of the twentieth century. Nevertheless, the antemortem anatomic involvement of the cervical sympathetic tract in hanging did not garner substantial forensic attention over time. The scarcity of “facie sympathique” reporting could be because it is believed that only very strong neck pressure might injure the cervical sympathetic chain and because unilateral miosis might be considered a postmortem behavior of the pupil [29], although unusual and not well understood. Thus, whether the “facie sympathique” is due to an antemortem cervical sympathetic neck injury or if it represents a postmortem change in pupil diameter undoubtedly requires further research.

It would be intriguing for forensic investigation to concentrate on eyelid and iris details with the same attention usually paid to other hanging marks. This crude observational activity, hopefully with the help of a measuring tool to avoid subjective results, could be first used to evaluate whether, as per Etienne Martin, the term “facie sympathique” must be maintained (or not) in association with neck compression in hanging or, as per Minovici, it must be considered an unpredictable and unstable ocular mark. Moreover, processes for diagnosing Bernard-Horner syndrome in living people [30], postmortem computer tomography (CT) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [31], could be promising tools for detecting the integrity of the superior cervical ganglion prior to autopsy [32], although access to both of these techniques remains limited in forensic institutes. Finally, in living people, anatomical cervical sympathetic integrity is also investigated by the chemical response of the pupils to pharmacological tests [30, 33]. The use of these pharmacological tests postmortem has not been considered, although parameters of pupil reaction are used to establish the time since death through topical drugs that act directly on iris muscles, with divergent results [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] (Table 2) regarding the mechanism of this supravital phenomenon.

Conclusion

Undoubtedly, only a careful evaluation of all the available data may reduce the risk of a misinterpretation of death’s cause and manner, especially in the asphyxia-related deaths. Anyway, what can be drawn from the aforementioned data? First, forensic investigators have maintained an interest in “facie sympathique” in hanging over time, although this mark is described differently from Etienne Martin’s description (1899) without further evidence regarding antemortem versus postmortem pathogenetic mechanisms. Hence, the historical disagreement between Etienne Martin and Nicolae Minovici regarding the interpretation of the “facie sympathique” has not been overcome, and this facial mark cannot yet be recommended as a diagnostic tool. For this reason, the opportunity to appreciate ocular inequality is of forensic interest, and the “facie sympathique” mark should be a focus of studies aimed at identifying signs of vitality in hanging and in any fatal upper neck trauma, especially when no skin marks are evident.

Key points

-

1.

Forensic researchers have long distinguished antemortem from postmortem hanging markers.

-

2.

In 1899, Etienne Martin first noted unilateral miosis with partial superior eyelid closure (ptosis) on the opposite side of the knot in hanging. He named this presentation “facie sympathique” due to its resemblance to the face of patients who underwent sympathectomy.

-

3.

This facial mark is scarcely reported in the forensic literature and, when mentioned, is described differently from its original meaning. Thus, the “facie sympathique” cannot be recommended as a diagnostic tool in establishing antemortem from postmortem neck compression.

-

4.

For these reasons, the evidence of ocular inequality in hanging might maintain forensic interest and allow the consideration of the “facie sympathique” mark in fields of research focused on signs of vitality in hanging and any fatal upper neck trauma, especially when no skin marks are evident.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or from the corresponding author.

References

World Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643 . Accessed 10 Oct 2022.

Fazel S, Runeson B. Suicide. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:266–74.

Legaz Pérez I, Falcón M, Gimenez M, et al. Diagnosis of vitality in skin wounds in the ligature marks resulting from suicide hanging. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2017;38(3):211–8.

Sharma BR, Harish D, Sharma A, et al. Injuries to the neck structures in deaths due to constriction of the neck, with special reference to hanging. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008;15:298–305.

Clement R, Guay JP, Sauvageau A. Fractures of the neck structure in suicidal hangings: a retrospective study on contributing variable. For Sci Inter. 2011;207:122–6.

Zatopkova L, Janik M, Urbanova P, et al. Laryngohyoid fractures in suicidal hanging: a prospective autopsy study with an updated review and critical appraisal. For Sci Inter. 2018;290:70–84.

Nikolic S, Micic J, Attanasijevic T, et al. Analysis of neck injuries in hanging. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2003;24(2):179–83.

Fracasso T, Pfeifer H. Simon’s bleeding in case of incomplete hanging. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2008;29(4):352–3.

Tawil M, Serinelli S, Gitto L. Simon’s sign: case report and review of the literature. Med Leg J. 2022;90(1):52–6.

Hejna P. Amussat’s sign in hanging – a prospective autopsy study. J For Sci. 2011;56(1):132–5.

Etienne M. Le facies sympathique des pendus, Archives d'anthropologie criminelle de criminologie et de psychologie normale et pathologique. Lyon: Éd. Storck. 1899. https://criminocorpus.org/fr/bibliotheque/page/9565/ Accessed 28 Oct 2022.

Lacassagne A. Précis de Médicine légale. Paris: Éd. Masson et C. 1906.

Jaboulay M. La section du sympathique cervical dans l’exophtalmie. Lyon: Éd. Lyon Médical. 1896.

Minovici N. Études sur la pendaison. Hachette Livre Bnf 1.10.2020 (ISBN 978–2329493091). 1905.

Minovici N. Studiu asupra spânzurării. UK: Ed. Kessinger Publishing (ISBN 9781165677634). 1904.

Marchetti D, Boccardi L, Biondo D, Cittadini F. Oculo-sympathetic findings in cases of neck trauma. A systematic review. Rev de Medicina Leg. 2018;26(4):419–28.

Andriuskeviciute G, Chmieliauskas S, Jasulaitis A, et al. A study of fatal and nonfatal hangings. J Forensic Sci. 2016;61(4):984–7.

Yakvtsova I, Hurov O, Nikonov V, et al. Diagnostics of mechanical asphyxia – experience of foreign countries (literature review). ScienceRise: Med Sci. 2021;3(42):45–9.

Payne-James J, Busuttil A, Smock W. Forensic medicine: Clinical and pathological aspects. 1st edition. New York: Greenwich Medical Media Publisher. 2002.

Pholtan Rajeev SR. Forensic science on hanging in ancient Siddha Tamil Text – systematic comparative study. J Forensic Res Crim Investig. 2021;2(2):78–83.

Chanana A, Hakumat R, Jagdish G, Vijay A. Unusual changes in eyes in a case of a typical hanging- role of cervical sympathetic system. J Punjab Acad Forensic Med Toxicol. 2003;3:19–21.

Bardale R. Principle of forensic medicine and toxicology. Ltd India, New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publisher (P). 2011.

Biswas G. Review of forensic medicine and toxicology. Ltd India, New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publisher (P). 2012.

Polson CJ, Gee DJ, Knight B. Hanging. In: Polson CJ, Gee DJ, Knight B, editors. The essentials of Forensic Medicine. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1985.

Weimann W, Prokop O. Atlante di Medicina Legale. Roma: PEM Ed. 1966.

Bernard C. De l’influence du système nerveux grand sympathique sur la chaleur animale. CR de l’académie des Sciences. 1852;34:472–5.

Best AE. Pourfour du Petit’s experiments on the origin of the sympathetic nerve. Med Hist. 1969;13(2):154–74.

Sègura P, Speeg-Schatz C, Wagner JM, Kern O. Le syndrome de Claude Bernard-Horner et son contraire, le syndrome de Parfour du Petit, an anesthésie-réanimation. Ann Fr Anesth Rèanim. 1998;17(7):709–24.

Sołek-Pastuszka J, Zegan-Baranska M, Biernawska J, et al. Atypical pupil reactions in brain dead patients. Brain Sci. 2021;11:1194–200.

Reede DL, Garcon E, Smoker WRK, Kardon R. Horner’s syndrome: clinical and radiographic evaluation. Neuroimag Clin N Am. 2008;18:369–85.

Gascho D, Heimer J, Tappero C. Relevant findings on postmortem CT and postmortem MRI in hanging, ligature strangulation and manual strangulation and their additional value compared to autopsy – a systematic review. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2019;15:84–92.

Saylam CY, Ozgiray E, Orhan M, Cagli S, Zileli M. Neuroanatomy of cervical sympathetic trunk: a cadaveric study. Clin Anat. 2009;22(3):324–30.

Thompson HS, Mensher JH. Adrenergic mydriasis in Horner’s syndrome. Hydroxyamphetamine test for diagnosis of postganglionic defects. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;72:72–480.

Marshall JN. On the changes in the pupil after death and the action of atropine and the other alkaloids on the dead eye. Lancet. 1885;286–288.

Prokop O, Fϋnfhausen G. Uber postmortale Pupillenreaktion auf pharmakologische Reize. In: Schleyer F. Determination of the time of death in the early post-mortem interval. In: Lundquist F. Methods of Forensic Science. London/New York J. Wiley & Sons. 1963;2:261–64.

Bardzik S. The efficiency of methods of estimating the time of death by pharmacological means. J Forensic Med. 1966;13(4):141–3.

Klein A, Klein S. Die Todeszeitbestimmung am menschlichen Auge. Dresden University: MD Thesis, 1978. In Hensgge C, Knight B, Krompecher T, Madea B, Nokes L. The estimation of the time since death in the early post-mortem period. 2nd ed. Arnold, London. 2002;139–142.

Orrico M, Melotti R, Mantovani A, et al. Criminal investigations: pupil pharmacological reactivity as method for assessing time since death is fallacious. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2008;29(4):304–8.

Larpkrajang S, Worasuwannarak W, Peonim V, et al. The use of pilocarpine eye drops for estimating the time since death. J Forensic Leg Med. 2016;39:100–3.

Koehler K, Sehner S, Riemer R, et al. Post-mortem chemical excitability of the iris should not be used for forensic death time diagnosis. Int J Legal Med. 2018;132(6):1693–7.

Shivam D, Monika C, Kumath Manish K, Gupta M. Determining pupillary reaction time using pilocarpine eye drop – a postmortem study journal of Indian. Acad Forensic Med Year. 2022;44(Suppl):2–5.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The manuscript has not been published and is not under submission elsewhere. All the authors approved the manuscript to Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest. The paper was carried out without any source of funding or disclaimers. All authors equally contributed to the paper. The two figures have the permission from the copyright owners.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marchetti, D., Santoro, L. & Mercuri, G. The “facie sympathique” sign in hanging: historical background, forensic review, and perspectives. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 20, 261–267 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-023-00603-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-023-00603-8