Abstract

In the United States National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health have mandated training STEM doctoral students in the ethical and responsible conduct of research to improve doctoral students' ethical decision-making skills; however, little is known about the process and factors that STEM faculty and graduate students use in their decision-making. This exploratory case study examined how four triads of chemistry faculty and their doctoral students recruited from three research universities in the eastern United States engaged in ethical decision-making on issues of authorship, assignment of credit, and plagiarism. A mixed-methods approach involving the administration of an online survey consisting of three open-ended case studies followed by a think-aloud interview was utilized. Participants were found to use analogical reasoning and base their decision-making on a common core set of considerations including fundamental principles, social contracts, consequences, and discussion with an advisor, often using prior personal experiences as sources. Co-authorship did not appear to impact the doctoral students' ethical decision-making. Gender may play a role in graduate students' decision-making; female doctoral students appeared to be less likely to consider prior experiences when evaluating the vignettes. Graduate students' lack of knowledge of the core issues in the responsible conduct of research, coupled with their lack of research experience, and inability to identify the core considerations may lead them to make bad judgments in specific situations. Our findings help explain the minimal impact that the current responsible conduct of research training methods has had on graduate students' ethical decision-making and should lead to the development of more effective approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is significant interest worldwide in the responsible conduct of research (RCR) training of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) graduate students as a means of informing and improving young scientists' responsible and ethical conduct of research (Carnero et al., 2017; Plemmons & Kalichman, 2018; Steele et al., 2016; Tang & Lee, 2020). In the United States, RCR training is mandated for all students supported with federal funding by either the National Institutes of Health (Ulane, 2011) or the National Science Foundation (NSF) (Córdova, 2017). What is known is that RCR training is effective in teaching graduate students the fundamental concepts of RCR (Antes et al., 2009). Case studies are frequently used in RCR training (Macrina, 2011; Macrina, 2014; National Academy of Sciences, 2018; National Academy of Sciences et al., 2009; Tang & Lee, 2020) and there is some evidence supporting their efficacy (Antes et al., 2009). Team-based learning appears to positively impact graduate and postdoctoral students' ethical decision-making (McCormack & Garvan, 2014). Mentoring also appears to be a piece of the puzzle though it may exert either a positive and negative influence depending on the type of mentoring used (research, survival, financial, and personal) and specific type of behavior involved (Anderson et al., 2007). What is known about students' ethical decision-making is that their gender (Langlais & Bent, 2014), self-perceptions, beliefs, and personality traits (Antes et al., 2007; Langlais & Bent, 2018) impact graduate students’ ethical decision-making. Prior exposure to ethical events and the severity of the consequences associated with these events also appear to sensitize and influence students' ethical decision-making (Mumford et al., 2006, 2007).

Authorship is an important fundamental concept in RCR training that has enormous professional significance in STEM education and research (Biagioli & Galison, 2003; Mabrouk & Currano, 2018). Recently, our lab investigated authorship decision-making in the context of undergraduate research partnerships (Abbott et al., 2020; Andes & Mabrouk, 2018). We learned that faculty do not engage in explicit discussion of authorship or the decision-making process that they use in making authorship or authorship hierarchy decisions with their graduate students or undergraduate researchers. So, we have initiated work to investigate faculty and graduate students' ethical decision-making on RCR issues related to authorship to learn what factors faculty and their graduate students consider when making ethical decisions on these issues, and to explore whether and how prior authorship experiences influence graduate students’ ethical decision-making.

Methodology

This study was reviewed and approved by the Northeastern University Institutional Review Board (#19–10-18) before any survey or interview work was conducted. Unsigned consent was used for surveys and a signed consent form was used for the think-aloud interviews.

Since little is known about how faculty and graduate students engage in ethical decision-making on issues related to the responsible conduct of research and because our objective was to develop a model for the process faculty and graduate students use, a qualitative methodology seemed most appropriate. We chose the exploratory case study methodology because our goal is to learn how chemistry faculty and their graduate students engage in ethical decision-making on authorship-related issues and investigate what factors influence their decisions. To develop an accurate picture, it is imperative to consider the context in which faculty and their graduate students make these decisions at research universities specifically, in courses and their research groups. Since the issues being evaluated have no clear, single set of likely outcomes, an exploratory approach is appropriate. We decided to use a set of open-ended case studies in our work because, as mentioned, open-ended case studies are frequently used in RCR training and therefore are likely to be familiar to our faculty and graduate student participants. We used a two-pronged approach in our work engaging our participants as individuals in a survey followed by a think-aloud interview.

Research Design

Survey Design

The survey (see Appendix A) was designed to engage the participants in ethical decision-making on issues related to authorship and identify what factors the participants used when making their decisions. Participants were asked to evaluate three open-ended scenarios. In each, they were asked to determine whether a graduate student should discuss their concerns with their advisor and to identify their top three considerations when making their decision from a list of 14 randomly ordered items representing common decision-making considerations. Every effort was made to ensure consistency of these items across scenarios and to ensure items were specific and relevant to each scenario. In the first scenario, a graduate student learned that they were the second author on a now published paper after doing substantial work to revise a paper for publication. As such, this scenario focused on the assignment of credit, authorship requirements, and authorship hierarchy. The second scenario highlights a graduate student, now having second thoughts, after plagiarizing content for the background section of a federal grant proposal soon to be submitted by their faculty advisor; the last scenario focused on an ill graduate student contemplating plagiarism on a paper for a graduate course. Consistent with best practices, we captured our participants' demographics at the end of the survey.

Survey Administration

Semi-scripted think-aloud interviews (see Appendix A) were conducted following the administration of the survey (see Appendix B). The think-alouds were useful in evaluating the reliability and face validity of the survey items and provided much rich data on the participants’ ethical decision-making process that would never have been captured using a survey alone. After participants worked their way through the survey in the think-aloud, the participants were asked whether the wording of the directions, scenarios, and items was confusing or difficult to understand. Participants were also asked whether the items reflected their considerations when evaluating the scenario. Content validity of the survey was initially assessed through the review of the survey by the study’s three authors and six faculty and two advanced doctoral students participating in the Humanities Center Faculty Fellows program. Subsequently, the refined survey and think-aloud script were tested through the recruitment and participation of two students who completed the survey and then participated in a practice think-aloud interview prior to the start of the study. The adequacy of the survey instrument is supported by the fact that none of the twelve study participants offered any suggestions for additional items that would have reflected their considerations.

Design of Think-aloud Interviews

Each participant was interviewed separately. Before the interview, each participant was provided a copy of their answers to the survey and a blank survey. During the think-aloud interview (see Appendix B), participants were asked to walk through their decision-making process for each scenario and explain why they selected the items they chose as the most important factors in making their decision and why they ranked the three items in the order that they did. After discussing the three scenarios, participants were asked a set of 4 exit questions to evaluate which scenario was the easiest and which was the most challenging to evaluate and why they felt that way. Participants were also asked what, if anything, they learned by participating. Each participant received a $50 honorarium at the end of the think-aloud interview.

Recruitment and Think-aloud Interviews

We emailed the chairs of 7 chemistry departments and requested the names of faculty whom we might contact and invite to participate in our study. Four chairs responded and provided us with names of faculty whom we could contact. Twelve faculty were then emailed and invited to participate. Six responded and four faculty were ultimately recruited. Our invitation email explained the purpose of our study and that we sought to recruit triads consisting of faculty and two current doctoral students, one of whom had co-authored one or more research papers with their advisor and a second student who had not yet co-authored any publications with their faculty advisor. Triads were recruited one at a time. Faculty who agreed to participate were asked to provide contact information for two current graduate students who fit the criteria above. Once recruited, each participant was provided a link to the survey (Appendix A). Thirty-minute semi-scripted think-aloud interviews (Appendix B) were conducted within 2 weeks of when each participant finished taking the survey. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, nine participants representing three triads were interviewed via Zoom.

The think-aloud interviews were rich in content. Interviews with the four participating faculty varied between 38 and 55-min. Discussions with the graduate students were significantly shorter and varied between 14 and 29 min with one exception. A male graduate student who had extensively published with his advisor spoke with us for 46-min. All interviews were recorded and transcribed by one member of the research team as soon as practical after the interview. Transcripts were vetted for accuracy by a second member of the research team, usually the principal investigator. All personal information and university names were removed from the transcripts to protect confidentiality. To support the authenticity of the data, actual quotes appear throughout this manuscript that represent the participants’ spoken words. This was done to fairly and faithfully capture the true meaning of the participants’ expressed views. This represents a best practice in qualitative research and supports the trustworthiness of our study.

Demographics

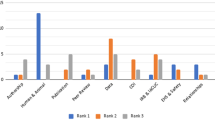

We sought to interview research triads from different universities representing different subdisciplines of chemistry. We recruited 4 triads from the chemistry departments at 2 private research universities and 1 public university in the eastern United States. Our participants were diverse in gender and ethnicity (see Fig. 1). Three of the four faculty recruited were full professors and the fourth was a tenured associate professor. Each faculty member represented a different subdiscipline of the field of chemistry, specifically, chemical education, chemical biology, physical chemistry, and organic chemistry. Eight chemistry doctoral students were recruited to participate. Two graduate students were recruited in each triad, one had prior publication experience with their faculty advisor and the other hasn’t yet published. Among the four graduate students who hasn’t published with faculty advisors, one was in their first year, two were third-year students, one was in their fourth year. Two of the four graduate students who had publication experiences were in their second year. Another was in their third year and still another was in their sixth-year. Among these eight graduate students, seven of them were U.S. educated. One student was an international student who received their bachelor’s degree in China.

Data Analysis

All the survey responses were downloaded and analyzed in Excel. All anonymized interview data were transcribed, and the transcripts were independently vetted by two members of the research team. The interview data were coded in NVIVO v. 12 (qualitative analysis software). Both researchers used open coding and worked through each transcript line-by-line independently, to identify codes representing recurrent ideas, themes, and actions that were explicitly expressed in the transcript. These ideas, themes, and actions became coding nodes when, after comparison, the pair of coders agreed that these themes were common and worth further examination. After agreeing upon all the codes for a single transcript, the iterative process was repeated until all 12 transcripts were coded. Evidence supporting theoretical saturation comes from the fact that no new codes were identified in the last two think-aloud interview transcripts and is consistent with sampling guidelines and expectations from the qualitative methods literature (Guest et al., 2006). Confirmability of the coding scheme was demonstrated when a third member joined the research team. This member re-examined and reanalyzed previously acquired and coded interview transcripts assuring that the conclusions which were being drawn were genuinely grounded in the data. Inter-rater reliability was evaluated using Cohen's Kappa, which considers chance agreement between the coders (Mabmud, 2010). The overall agreement (k = 0.9) supports the reliability of the coding scheme. A threshold of kappa greater than 0.7 is generally considered satisfactory. The codes were then categorized thematically. Through constant comparison analysis, categories and codes were subsumed and reorganized under a smaller set of categories. Ultimately, this led to the creation of two mind maps for the major categories: authorship requirements and decision-making elements.

Results and Discussion

Eight of the 14 items were selected at least once by a participant as one of their top three considerations. This suggests that the number of items was appropriate. Six items "Advisor has power over student's present and future, so it is important to tread lightly," "Advisor's opinion of the student may be diminished," "Advisor is nice and understanding," "Advisor is stern and mean," “In denial,” and “It is important to avoid conflict with one’s advisor” were not selected by any participant. However, one or more participants mentioned these items during the think-aloud interviews as additional considerations. Consequently, these items were retained in the survey as they do appear to be valid considerations.

To ensure that the scenarios were neither too challenging nor overly simplistic, we asked the participants at the end of the think-aloud to rate the overall difficulty they had in evaluating the scenarios on a scale from 1 (easiest) to 10 (most difficult). Individual participants' evaluations varied between 2 and 8 with six of the participants rating the difficulty between 2 and 4. We also asked the participants which of the three scenarios they found easiest to evaluate and which they found the most difficult, to further ensure that the scenarios were equally challenging to evaluate. Evaluations of each of the scenarios ranged widely with no scenario either consistently evaluated as easy or difficult by any category of participants (faculty, graduate students who were published, graduate students who have not yet published, males or females).

Survey Data

The top-3 ranked items for each of the three scenarios are summarized in Table 1. One or more participants selected 8 of the 14 items in their selection of the most important considerations. This suggests that individuals valued a wide array of considerations when evaluating the scenarios. However, a review of Table 1 demonstrates that there was a common core set of items that were consistently and frequently selected by the participants overall. Furthermore, several items were frequently selected across all four teams and all three scenarios. “Fundamental principle” (32), “Discuss with advisor” (25), and “Consequences” (23) were the top 3 choices across all three scenarios.

Scenario 1

Scenario 1 focuses on issues of assignment of credit and authorship hierarchy. In this scenario, our participants appeared to value 4 of the 14 decision-making considerations. Participants frequently chose “Discuss with advisor” (10), “Fundamental principle” (9), and “New social contract” (8). A smaller number selected “Consequences” (4). Other items selected infrequently by participants included “External entity requirements” (3), and “Right is right and wrong is wrong” (1). All three members of Triad 1 selected “Journals have requirements.” This identification was unique to this triad.

Scenario 2

Scenario 2 focuses on the issue of plagiarism on a federal grant proposal and explores the significance of repercussions to other individuals beyond the student in the context of the research group. This scenario elicited the narrowest range of the top 3 of 14 items. We speculate that this likely reflects the lack of personal experience that the graduate students in our study had with research grants and grant writing (see below). All the participants selected “Fundamental principle” (12). Nearly everyone selected “Consequences” (10) as one of their top 2 items. Other frequent selections were “External entity requirements” (7), and “Discuss with advisor” (6). Only one additional item “Right is right and wrong is wrong” was selected by any participant as a top 3 consideration.

Scenario 3

Scenario 3 also focuses on the issue of plagiarism. Here, however, the context is the academic classroom. Once again there are potentially serious repercussions but only for the student who is the focus of the scenario. The participants identified the widest range of items when evaluating this scenario. Participants frequently chose "Fundamental principle" (11), "Consequences" (9), and "Discuss with advisor" (9). There was a strong agreement regarding the most important consideration; “Fundamental principle” was selected by 8 participants as the most important consideration. There was also strong consistency in the items selected by the faculty participants. Three of the four faculty identified these same top 3 three items. Other considerations identified included “If anyone has been in this position” (1), “New social contract” (1), “Avoid conflict with advisor” (1), “External entity requirements” (1), and “Right is right and wrong is wrong” (1). Four of these were selected by graduate student participants.

Limitations

One limitation of this exploratory case study was the sample consisted of 12 participants, representing four research groups in four different sub-fields of chemistry at 2 private and 1 public research university located in the eastern United States. Other individuals in chemistry departments at other universities and in other countries may have different knowledge and experiences and therefore they may hold views that were not represented in our study. Second, there is an over-representation of female participants in our study (9 out of 12 total). Third, our participants self-selected to participate so there is likely some self-selection bias. In addition, our results are based on survey and think-aloud interview data captured at a single point in time. As such our findings should be considered a starting point for broader studies in this area.

Prior Ethics Training

All the graduate student participants reported completing a required ethics workshop or course as part of their undergraduate or graduate training before participating in our study. All the participants completed their most recent ethics training in the United States. However, none of them appeared to base their decision-making on case studies or any other information from the training they received. Based on our interviews, there is some evidence that a combination of factors may have been responsible for the lack of impact of this training on the graduate students. Several students made comments regarding the timing of the training, typically completed during the first year of graduate study, like “It’s been a while” or “if I remember right.” The generality of the content was identified as another reason for their perception of the lack of relevance of the training. One student stated, "It doesn't really apply to specific situations that maybe we as chemists would fall under." Another student said "It's not very well taught, unfortunately. It's a log of patents and some weird situations." The lack of impact was consistent with the efficacy of current ethics training methods as reported in the literature (Antes et al., 2009).

Personal Experience

In the think-aloud interviews, we discovered that the study participants frequently used prior experience with similar situations when evaluating the three scenarios. Participants appeared to identify common elements, draw comparisons between the scenario and a specific prior experience, identify common elements in the two situations, and then identify their top considerations. Consider Faculty 1’s explanation of their analysis of scenario 3:

So, I have firsthand experience with it…including one student, who heavily, who just cut and paste stuff from websites onto a paper in a course on ethics… And he heavily cut and paste parts of what he was supposed to write from authors available on the web, and [the professor] sent me his paper as an attachment with all those sections, highlighted asking, what to do. And uh, so I had to deal with that situation very carefully. I did see merit there, so he wasn't kicked out. He was explained very strenuously though, not to do that ever again.

Table 2 summarizes the participants' use of personal experience in evaluating each of the scenarios. We are aware of at least one other qualitative study (Gibson et al., 2014) focused on ethical decision-making that reported the frequent use of personal experience by participants in evaluating ethical scenarios and discussing their reasoning. In this study, eight participants including all four faculty, three of the graduate students with prior publication experience, and one unpublished male student discussed prior experience during their think-aloud interviews. Participants appeared to leverage personal experience most frequently when evaluating the authorship scenario 1 and explaining the importance of the item “Discuss with advisor” (5), “Fundamental principle” (3), or “Consequences” (2).

Overall, the graduate student participants appeared to be less likely to use personal experience in evaluating the scenarios. Three of the four graduate students with publication experience leveraged prior experiences in evaluating scenario 1. Two graduate students leveraged personal experience when evaluating the first and third but not the second scenario. None of the students seemed to use personal experience when evaluating the second scenario focused on grantsmanship. One possible explanation for this is that the graduate students had no previous grant writing experiences upon which to draw. So, we reached out to our graduate student participants afterward to find out if they had had any experience working on grants preceding our interview. Indeed, only one of the 8 graduate student participants reported having participated in any form of grant writing prior to their interview.

We saw some evidence that may indicate a gendered effect in graduate students’ use of personal experience when making ethical decisions on authorship-related issues. Four of the five female graduate students participating in the study did not refer to any prior events when evaluating any of the scenarios during their think-aloud interviews. Three of these students had no publication experience. All three male graduate students, though, recounted one or more personal stories when discussing their reasoning during the think-aloud interviews. It may simply be that the four female graduate students did not think to mention prior experiences during the interview; our prompt may not have been sufficient/appropriate to elicit this information, and, of course, our study was small. Nonetheless, the female students appear to be less likely to consider personal experience when making ethical decisions on authorship-related issues. Langlais and Bent (2014) reported, based on scores from Mumford's Ethical Decision Making test, (Mumford et al., 2006) that the female graduate student participants in their study were more ‘ethical’ in their decision-making than the males. Given Langlais and Bent’s findings, we believe our observation of possible gendered differences is an issue that merits further study.

Reputation

We also identified "Reputation" as another important consideration from the think-aloud data. We defined reputation as "the image one has as a scientist within the field." As summarized in Table 3, "Reputation" was mentioned by 9 out of 12 participants. All 4 faculty members mentioned "Reputation" in at least one scenario. 2 of the 4 graduate students who had publication experience considered "Reputation" when explaining their reasoning process during the interview, but both only mentioned it in one of three scenarios. To be specific, the published student from triad 1 thought about "Reputation" in scenario 2 while the published student from triad 3 considered it while evaluating items in scenario 1. Out of the 9 participants who mentioned "Reputation," the remaining 3 graduate students had not co-authored papers. Two of the 3 unpublished female students valued "Reputation" in 2 scenarios (triad 2: scenarios 1 and 2; triad 3: scenarios 2 and 3). During the interview, all participants considered the negative effects on graduate students themselves, the faculty advisor, and overall lab in the scenarios. We found faculty members are more likely to relate issues to "Reputation" and spontaneously share their thoughts about "Reputation" with us. Graduate students who had published were less likely to consider "Reputation" in comparison with those who had not published. However, there was no evidence that the faculty influenced the students. Moreover, lab culture may be an explanation for the consideration of "Reputation". For example, everyone in triad 3, valued "Reputation", demonstrating the possibility the lab values reputation through implicit or explicit discussion.

Theoretical Model for RCR Decision Making on Authorship-Related Issues

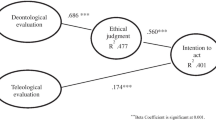

Overall, there appears to be a common set of primary decision-making elements driving our participants' evaluation of all three scenarios. We have incorporated these elements into a preliminary theoretical model for ethical decision-making on authorship-related issues shown in Fig. 2. These core elements include "Fundamental principle," which as mentioned earlier was selected most frequently (32 times across all three scenarios), "Discuss with advisor," (25), and “Consequences” (23). In addition, looking holistically across the three scenarios, receiving credit, funding agencies taking FFP seriously, and “Reputation” all seem to represent specific forms of “consequences.” The “social contract” also appears to be an important consideration though we note that this item was primarily a consideration in the authorship scenario. Finally, as we noted above, participants seemed to map to specific considerations whenever they had prior experience dealing with what they perceived to be a similar situation.

Comparison Between Research Triads

We saw evidence of different reasoning patterns between the different research groups. For example, triad 1 was the only research group to discuss and place a significant value specifically on journal requirements (“External entity requirements”) as a top 3 consideration in evaluating scenario 1. Every member of the triad considered this selection the third most important consideration. This likely reflects the values of the faculty advisor. The influence of the faculty however does not appear to be strong as evidenced by the variety of considerations used by the different participants in each triad.

Faculty versus Graduate Students

There was general consistency in the faculty’s top 3 ethical considerations. “Fundamental principles,” (12) "Consequences," (8) and "Discuss with advisor" (7) were common choices. However, there was also evidence of individual differences. For example, faculty 1 valued "External entity requirements," as a consideration in their evaluation of scenario 1, which was not selected by the other faculty members. “Fundamental principle,” (20) “Discuss with advisor,” (17) and “Consequences” (12) were also the most frequently invoked selections among the graduate students. Overall, there was good general agreement between the faculty and graduate students’ top selections. Among the top selections, across all three scenarios, both faculty and students selected “Fundamental principle” as their number one consideration. Faculty, however, considered “Consequences” before “Discuss with advisor” and students found it more important to consider “Discuss with advisor” before considering “Consequences.”

We saw some evidence in our study that the act of co-authorship may influence graduate students’ ethical reasoning on authorship-related issues (see Table 1). For example, both the faculty and the graduate student with publication experience in Triads 1 and 2 identified the same three considerations in evaluating scenario 1. However, overall, the top 3 considerations in evaluating all three scenarios identified by the published graduate students were no more similar to their faculty advisor’s considerations than those of their unpublished peers. There was also some variation in the top 3 considerations of the graduate students in each triad, which suggests that the influence of peers working in the same group may not be a significant factor affecting individual graduate students’ ethical decision making on authorship related RCR issues.

Six items “Advisor’s opinion of student may be diminished,” "Advisor has power over student's present and future, so it is important to tread lightly," "Advisor's opinion of the student may be diminished," "Advisor is nice and understanding," "Advisor is stern and mean," “In denial,” and “It is important to avoid conflict with one’s advisor” were not selected by anyone as a top 3 consideration. However, these items were consistently identified as the least important of the 14 considerations listed on the survey. With the exception of “In denial,” five of these items reflect concerns that a student might have if they were uncertain about their relationship with their advisor. In our previous work, the power dynamic was found to be an important issue affecting authorship decision-making in undergraduate research partnerships at research universities (Abbott et al., 2020). Our data here suggest that while power may be a consideration, it was not a major factor in our graduate student participants’ decision making.

The Role of Analogies in Ethical Decision-Making

Social psychologist Kevin Dunbar’s research group (Blanchette & Dunbar, 2000; Dunbar, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2000, 2001; Dunbar & Blanchette, 2001; Dunbar & Fugelsang, 2005) spent over a decade investigating in vivo/in vitro how scientists think and how their reasoning allows them to discover and explain new phenomena. Scientists appear to use analogical thinking most frequently, e.g., when formulating new concepts, designing experiments, interpreting data, and troubleshooting (dealing with unexpected results) (Dunbar, 2001). Researchers will often start by using local analogies and identifying superficial features. If these are unsuccessful, they then investigate more distant analogies using deeper structural elements. According to Dunbar's work over 50% of the analogies scientists make are based on deep rather than superficial features (Dunbar, 1995, 1997). It is the ability to identify deeper structural features that leads to productive analogies when dealing with unexpected results. Furthermore, analogical reasoning appears to be useful as it forces scientists to identify the critical structural elements in the problem. The use of analogies appears to correlate with experience; graduate students were reported to create few analogies while postdocs and faculty made many (Blanchette & Dunbar, 2000). Emotion associated with the source analog can also impact the strength of the analogy (Blanchette & Dunbar, 2001). Inexperienced young scientists tend to focus on superficial features which may lead them to use ineffective analogies. However, engaging student scientists in generating their own analogies appears to help them identify the salient structural similarities generating more robust analogies (Blanchette & Dunbar, 2000).

As we discussed earlier, many participants, including all the faculty in our study recounted stories from their past when discussing their rationale and made analogies between their prior experiences and the situations depicted in the scenarios. In Dunbar’s work (Dunbar, 1997), analogies were invoked 50% of the time when the goal was to explain. In our think-aloud interviews, we asked our participants to explain the basis for their selections. As in Dunbar's work, many of the analogies our participants used mapped within the same domain (source and target), for example, prior experiences in authorship mapped to scenario 1, prior experiences with funding agencies mapped to scenario 2, and prior experiences either as an instructor or student in the classroom were mapped to scenario 3. Both faculty and graduate students in our study told us that it was easier to evaluate the scenarios if they had prior experience. When asked which scenario was easiest to evaluate, one faculty member stated: “All of them because I lived through it. It like wasn't hard.” Students told us that they had an easier time evaluating the scenarios if they had prior experience. One graduate student said:

Yeah. The hardest one for me was the first scenario because I'm still in my early stages of my PhD and I haven't really gotten involved in, um, like I haven't, I guess, I don't know… Like I haven't really experienced that scenario. But with the other two scenarios, I've experienced my students cheating, I've experienced like my um, my fellow classmates like, uh, having to, to just, um, leave the class or not continue their program because they have cheated. So, it was easier for me to, to sort of in a way relate with the other scenarios from experience rather than just relate with first scenario because I haven't really had any conversation about authorship up until this point. It was very like easy in terms of like my advisor and the people I've worked with because it, it just made sense.

We posit scientists and student scientists use analogical reasoning in ethical decision-making on RCR-related issues such as authorship and plagiarism. Since we use analogies so frequently in our day-to-day work, is it any surprise that we would use this reasoning in our evaluation of ethical issues affecting our work? We believe that the elements identified in our theoretical model may represent some of the critical deep structural elements that scientists use in making ethical decisions on RCR issues (Fig. 1). As such, we believe that the identification of these elements should be useful in both the design of RCR training and training materials including case studies, as well as the analysis of these cases.” Modern research takes place in a complex, inherently social context, specifically, the research group (Degn et al., 2018). Groups are often heterogeneous, constituted of individuals with varying levels of technical knowledge and experimental expertise and this knowledge and expertise often represents different disciplines. Dunbar demonstrated that the makeup of the research group and its dynamics can modulate individual biases, foster recognition of inconsistencies, and produce conceptual change and insight (Dunbar, 1995). These characteristics can also inhibit these actions when the members come from similar backgrounds and possess a similar knowledge base. Student scientists may be hampered in their ability to engage in productive analogical reasoning on RCR issues both due to their limited content knowledge and experience in identifying good analogies and will often focus on superficial structural elements as a result (Novick, 1988). It likely doesn't help that some faculty at research universities do not explicitly discuss authorship or other RCR issues in their research groups. REF.

As mentioned earlier, case studies are often used in RCR training workshops where the participants are simultaneously being introduced to the RCR concepts for the first time. The case studies used in these workshops are often open-ended and the workshops typically engage groups of inexperienced students in discussion. Successful solution of open-ended case studies (target) requires a fundamental understanding of the RCR concepts involved, the ability to draw on (similar) source situations, and the ability to identify the underlying structural features to make an analogy and successfully map between the source and target. We posit that current training methods may be ineffective in changing ethical behavior because some student scientists may be deficient in one or even all three areas and this, in turn, may make it difficult for them to engage in productive analogical reasoning when faced with significant ethical challenges in the classroom or the research laboratory.

If we desire our students to be able to engage in complex ethical decision-making on emergent scientific discoveries, then perhaps we need to rethink our training methods. We would like to offer the following three suggestions based on our work: (1) Initial RCR training to first focus on introducing students to the critical RCR issues. (2) At a separate time, engage students in the analysis of case studies with an emphasis on getting them to identify the critical structural issues in the scenario. Finally, after introducing the student scientists to the fundamental RCR concepts and engaging them in a productive analysis of prior cases, (3) engage teams of expert and student scientists in the explicit analysis of open-ended case studies where the discussion focuses on analogical reasoning in which the source and targets and the critical structural elements are explicitly identified and discussed. In these discussions, we believe based on Dunbar's work, students should be engaged in actively generating analogies using their own prior knowledge and experiences so that they can learn how to identify the critical, relevant structural elements and develop their own robust analogies.

In summary, in this exploratory case study, we have shown that chemistry faculty and students engaging in ethical decision-making on authorship-related issues base their decision-making on a common core set of considerations. These include fundamental principles, a new social contract, consequences, and a discussion with an advisor. Participating in authorship experiences does not appear to significantly impact graduate students' ethical decision-making on authorship-related issues. Faculty and graduate students approach ethical decision-making using the same type of reasoning that they use in their research, specifically, analogical reasoning. Frequently, they use personal experiences as a source, to understand and evaluate new ethical dilemmas. Additionally, we saw some evidence that gender may play a role in graduate students’ decision-making. Next steps include testing the generalizability of our findings to other groups and disciplines, probing the influence of gender, and investigating scientists’ ethical reasoning for a wider array of RCR issues.

Data Availability

The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Change history

16 June 2022

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article ORCiD 0000-0003-0549-7426 for Yiyang Gao, ORCiD 0000-0002-9571-9186 for Jasmin Wilson and ORCiD 0000-0003-4965-1448 for Patricia Ann Mabrouk were inadvertently omitted.

References

Abbott, L. E., Andes, A., Pattani, A. C., & Mabrouk, P. A. (2020). Authorship not taught and not caught in undergraduate research experiences at a research university. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(5), 2555–2599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00220-6

Anderson, M. S., Horn, A. S., Risbey, K. R., Ronning, E. A., De Vries, R., & Martinson, B. C. (2007). what do mentoring and training in the responsible conduct of research have to do with scientists’ misbehavior? Findings from a national survey of NIH-funded scientists. Academic Medicine, 82(9), 853–860. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31812f764c

Andes, A. & Mabrouk, P. A. (2018). Authorship in undergraduate research partnerships: A really bad tango between undergraduate protégés and graduate student mentors while waiting for professor godot. In Credit where credit is due: Respecting authorship and intellectual property, Vol. 1291, (pp. 133–158). American Chemical Society. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2018-1291.ch013

Antes, A. L., Brown, R. P., Murphy, S. T., Waples, E. P., Mumford, M. D., Connelly, S., & Devenport, L. D. (2007). Personality and ethical decision-making in research: The role of perceptions of self and others. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 2(4), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2007.2.4.15

Antes, A. L., Murphy, S. T., Waples, E. P., Mumford, M. D., Brown, R. P., Connelly, S., & Devenport, L. D. (2009). A meta-analysis of ethics instruction effectiveness in the sciences. Ethics and Behavior, 19(5), 379–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420903035380

Biagioli, M. & Galison, P. (Eds.). (2003). Scientific authorship: Credit and intellectual property in science. Routledge.

Blanchette, I., & Dunbar, K. (2000). How analogies are generated: The roles of structural and superficial similarity. Memory and Cognition, 28(1), 108–124. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03211580

Blanchette, I., & Dunbar, K. (2001). Analogy use in naturalistic settings: The influence of audience, emotion, and roles. Memory and Cognition, 29(5), 730–735. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03200475

Carnero, A. M., Mayta-Tristan, P., Konda, K. A., Mezones-Holguin, E., Bernabe-Ortiz, A., Alvarado, G. F., Canelo-Aybar, C., Maguiña, J. L., Segura, E. R., Quispe, A. M., Smith, E. S., Bayer, A. M., & Lescano, A. G. (2017). Plagiarism, cheating and research integrity: Case studies from a masters program in Peru. Science and Engineering Ethics, 23(4), 1183–1197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-016-9820-z

Córdova, F. A. (2017). Important notice No. 140. training in responsible conduct of research—A reminder of the NSF requirement. Internet: National Science Foundation Retrieved from https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/issuances/in140.jsp

Degn, L., Franssen, T., Sørensen, M. P., & de Rijcke, S. (2018). Research groups as communities of practice—A case study of four high-performing research groups. Higher Education, 76(2), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0205-2

Dunbar, K. (1995). How scientists really reason: Scientific reasoning in real-world laboratories. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of insight (pp. 365–395). MIT Press.

Dunbar, K. (1997). How scientists think: On-line creativity and conceptual change in science. In T. B. Ward, S. M. Smith, & J. Vaid (Eds.), Conceptual structures and processes: emergence, discovery, and change (pp. 461–493). American Psychological Association Press.

Dunbar, K. (1999). How scientists build models: Invivo science as a window on the scientific mind. In L. Magnani, N. Neressian, & P. Thagard (Eds.), Model-based reasoning in scientific discovery (pp. 89–98). Plenum Press.

Dunbar, K. (2000). How scientists think in the real world: Implications for science education. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(99)00050-7

Dunbar, K. (2001). The analogical paradox: Why analogy is so easy in naturalistic settings, yet so difficult in the psychological laboratory. In D. Gentner, K. J. Holyoak, & B. Kokinov (Eds.), The analogical mind: Perspectives from cognitive science (pp. 520). MIT Press.

Dunbar, K., & Blanchette, I. (2001). The in vivo/in vitro approach to cognition: The case of analogy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5(8), 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01698-3

Dunbar, K., & Fugelsang, J. (2005). Scientific thinking and reasoning. In K. J. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 705–726). Cambridge University Press.

Gibson, C., Medeiros, K. E., Giorgini, V., Mecca, J. T., Devenport, L. D., Connelly, S., & Mumford, M. D. (2014). A qualitative analysis of power differentials in ethical situations in Academia. Ethics and Behavior, 24(4), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2013.858605

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How Many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82.

Langlais, P. J., & Bent, B. J. (2014). Individual and organizational predictors of the ethicality of graduate students’ responses to research integrity issues. Science and Engineering Ethics, 20(4), 897–921. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-013-9471-2

Langlais, P. J., & Bent, B. J. (2018). Effects of training and environment on graduate students’ self-rated knowledge and judgments of responsible research behavior. Ethics and Behavior, 28(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1260014

Mabmud, S. M. (2010). Cohen’s Kappa. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of research design (pp. 188–189). SAGE Publications Inc.

Mabrouk, P. A. & Currano, J. N. (Eds.). (2018). Credit where credit is due: Respecting authorship and intellectual property (Vol. 1291) https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2018-1291. American Chemical Society. https://doi.org/10.1021/bk-2018-1291

Macrina, F. (2011). Teaching authorship and publication practices in the biomedical and life sciences. Science and Engineering Ethics, 17(2), 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-011-9275-1

Macrina, F. L. (2014). Scientific integrity: Text and cases in responsible conduct of research (4th ed.). ASM Press.

McCormack, W. T., & Garvan, C. W. (2014). Team-based learning instruction for responsible conduct of research positively impacts ethical decision-making. Accountability in Research, 21(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2013.822267

Mumford, M. D., Devenport, L. D., Brown, R. P., Connelly, S., Murphy, S. T., Hill, J. H., & Antes, A. L. (2006). Validation of ethical decision making measures: Evidence for a new set of measures. Ethics and Behavior, 16(4), 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb1604_4

Mumford, M. D., Murphy, S. T., Connelly, S., Hill, J. H., Antes, A. L., Brown, R. P., & Devenport, L. D. (2007). Environmental influences on ethical decision making: Climate and environmental predictors of research integrity. Ethics and Behavior, 17(4), 337–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420701519510

National Academy of Sciences. (2018). The online ethics center for engineering and science. Retrieved October 2019 from http://www.onlineethics.org/

National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. (2009). On being a scientist: A guide to responsible conduct in research: Third Edition. http://www.nap.edu/readingroom/books/obas/

Novick, L. R. (1988). Analogical transfer, problem similarity, and expertise. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 14(3), 510–520. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.14.3.510

Plemmons, D. K., & Kalichman, M. W. (2018). Mentoring for responsible research: The creation of a curriculum for faculty to teach RCR in the research environment. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(1), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9897-z

Steele, L. M., Johnson, J. F., Watts, L. L., MacDougall, A. E., Mumford, M. D., Connelly, S., & Lee Williams, T. H. (2016). A comparison of the effects of ethics training on international and US students. Science and Engineering Ethics, 22(4), 1217–1244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9678-5

Tang, B. L., & Lee, J. S. C. (2020). A reflective account of a research ethics course for an interdisciplinary cohort of graduate students. Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(2), 1089–1105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00200-w

Ulane, R. (2011). Update on the requirement for instruction in the responsible conduct of research. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Extramural Programs. Retrieved October 2019 from http://grants1.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-10-019.html

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Northeastern University Honors Program for an Honors Early Research Award and Rein Kirss and Ethan Reiter for helpful feedback that significantly improved our paper. PAM also wishes to thank the 2019-2020 Northeastern University Humanities Center Fellows for reviewing and feedback on the survey instrument and study design used in this work.

Funding

This research was funded by the Office of the Provost of Northeastern University (Boston, MA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PAM developed the study design, participated in all aspects of the data collection and analysis, and worked collaboratively with YG on writing this manuscript. JW helped develop the survey instrument and interview script and participated in the early data collection and analysis. YG refined the survey instrument and interview script, completed the data collection, analyzed all the study data, and contributed significantly to the writing of this manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures used in this study were in accord with Northeastern University’s Institutional Review Board (#19–10-18), which reviewed and approved the research protocol before the study was initiated and annually after that. Signed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article ORCiD 0000-0003-0549-7426 for Yiyang Gao, ORCiD 0000-0002-9571-9186 for Jasmin Wilson and ORCiD 0000-0003-4965-1448 for Patricia Ann Mabrouk were inadvertently omitted.

Appendices

Appendix A: Survey instrument

Scenario 1

List of characters

Dr. Lesley, professor of the lab in which Riley and Chris work.

Chris, first-year graduate student in Dr. Lesley's lab and second author on the paper Riley, recently graduated Ph.D. student in Dr. Lesley's lab and first author on the paper.

Scenario 1

Lesley asks Chris, a first-year graduate student who recently joined the lab, to complete a few experiments on a project that forms the basis of one chapter in Riley, a soon-to-be-graduated doctoral student’s dissertation to turn the chapter into a manuscript that will be submitted to Science, a prestigious and highly cited journal. Chris, Riley, and Dr. Lesley discuss the authorship criteria used in the lab as soon as Dr. Lesley decides that the work should be written up, and everyone agrees that Riley should be the first author and Chris should be the second author on the paper. The paper was submitted just before Riley is graduated. Three months later, Dr. Lesley received the reviews. The Editor has decided that major revision will be required before publication is warranted, but the good news is that the paper has not been rejected. To address the reviewers' concerns, all of Riley’s work must be repeated, and a series of new experiments must be carried out to confirm several critical issues. Dr. Lesley asks Chris to do this work and leans on Riley to rewrite the manuscript. The revised paper is resubmitted and published shortly afterward. Chris is surprised and upset to discover that they are the second author on the published paper. Chris wonders whether they should speak to Dr. Lesley.

Should Chris speak with Dr. Lesley?

Yes.

No.

Cannot decide.

Directions: Read over the 14 statements below and select only one of the 14 statements for choice 1, choice, 2, choice 3, and choice 4. 1 is the most important, and 4 is the least important.

-

1.

Dr. Lesley’s opinion of Chris will likely be improved

-

2.

Dr. Lesley’s opinion of Chris may be diminished

-

3.

A fundamental principle is involved; specifically, the first author usually does most of the work on the paper (Fundamental principle)

-

4.

The situation has changed, so a new social contract should be negotiated between Dr. Lesley and Chris (New social contract)

-

5.

If Chris doesn’t speak up, then Chris won’t get the credit they deserve for their work on the paper (Consequences)

-

6.

Right is right, and wrong is wrong

-

7.

Dr. Lesley has power over Chris’s present and future, so it is important to tread lightly

-

8.

Dr. Lesley is nice and understanding

-

9.

Dr. Lesley is stern and mean

-

10.

There is no issue here because Chris will likely be the first author next time (In denial)

-

11.

It is important to avoid conflict with one’s advisor

-

12.

It is important to learn how to discuss important issues with one’s advisor (Discuss with advisor)

-

13.

Every journal has authorship requirements (External entity requirements)

-

14.

Chris needs to find out if anyone else in the lab has been in this position (If anyone has been in this position)

Scenario 2

List of Characters

Dr. Nour, Zein's doctoral research advisor.

Zein, a third-year graduate student in Nour's group who helped Dr. Nour draft the background section of the NIH grant application.

Scenario 2

Dr. Nour asks Zein, a third-year graduate student, to help him draft the background section of an R21 NIH grant application that will support Zein’s work if funded. The grant deadline is three weeks away. The topic is an important one central to Zein’s doctoral research but one that Zein has been struggling to understand. Two weeks later, short on time and uncomfortable with the subject matter, Zein opts to paraphrase heavily using several highly cited published studies. Pressed for time, Dr. Nour incorporates Zein’s text verbatim into the final draft without taking the time to review Zein’s work. Zein wonders whether they should tell Dr. Nour what they did before submitting the grant application.

Should Zein speak with Dr. Nour?

Yes.

No.

Cannot decide.

Directions: Read over the 14 statements below and select only one of the 14 statements for choice 1, choice, 2, choice 3, and choice 4. 1 is the most important, and 4 is the least important.

-

1.

Dr. Nour’s opinion of Zein will likely be improved

-

2.

Dr. Nour’s opinion of Zein may be diminished

-

3.

A fundamental principle is involved; specifically, paraphrasing is a form of plagiarism and is unacceptable (Fundamental principle)

-

4.

The situation has changed, so a new social contract should be negotiated between Dr. Nour and Zein (New social contract)

-

5.

If Zein doesn’t speak up, then there could be serious repercussions (Consequences)

-

6.

Right is right, and wrong is wrong

-

7.

Dr. Nour has power over Zein’s present and future, so it is important to tread lightly

-

8.

Dr. Nour is nice and understanding

-

9.

Dr. Nour is stern and mean

-

10.

There is no issue here because it is unlikely that anyone will find any problem because Dr. Nour didn’t see one (In denial)

-

11.

It is important to avoid conflict with one’s advisor

-

12.

It is important to learn how to discuss important issues with one’s advisor (Discuss with advisor)

-

13.

Every funding agency takes issues involving falsification, fabrication, and plagiarism (FFP) seriously (External entity requirements)

-

14.

Zein needs to find out if anyone else in the lab has been in this position (If anyone has been in this position)

Scenario 3

List of Characters

Prof. Jones, professor of the research group in which Charlie works.

Charlie, a second-year graduate student in Prof. Jones' research group who is preparing for the qualifying doctoral exams.

Scenario 3

Charlie is a second-year graduate student preparing for the qualifying doctoral exams. Charlie struggled through the required coursework the first year of the program and has been attempting to compensate for poor course performance by strong research contributions in the research lab that they joined. In Prof. Jones’s research group, Charlie is well-liked and respected for their hard work and willingness to pitch in and help others when needed. Charlie becomes ill and gets behind working on the final paper in the last graduate course that they are required to take in their doctoral program. Pressed for time, uncomfortable with the subject matter, and concerned about their status in the graduate program, Charlie contemplates paraphrasing several paragraphs from a series of obscure published studies.

Should Charlie speak with Professor Jones?

Yes.

No.

Cannot decide.

Directions: Read over the 14 statements below and select only one of the 14 statements for choice 1, choice, 2, choice 3, and choice 4. 1 is the most important, and 4 is the least important.

-

1.

Prof. Jones’ opinion of Charlie will likely be improved

-

2.

Prof. Jones’ opinion of Charlie may be diminished

-

3.

A fundamental principle is involved; specifically, paraphrasing is a form of plagiarism and is unacceptable (Fundamental principle)

-

4.

The situation has changed, so a new social contract should be negotiated between Prof. Jones and Charlie (New social contract)

-

5.

If Charlie doesn’t speak up, then there could be serious repercussions (Consequences)

-

6.

Right is right, and wrong is wrong

-

7.

Prof. Jones has power over Charlie’s future in the doctoral program, so it is important to tread lightly

-

8.

Prof. Jones is nice and understanding

-

9.

Prof. Jones is stern and mean

-

10.

There is no issue here because it is unlikely that anyone will notice (In denial)

-

11.

It is important to avoid conflict with one’s advisor

-

12.

It is important to learn how to discuss important issues with one’s research advisor (Discuss with advisor)

-

13.

Every graduate course has final deadlines (External entity requirements)

-

14.

Charlie needs to find out if anyone else in the graduate program has been in this position (If anyone has been in this position)

Appendix B: Think-Aloud Script

Opening Statement: | Thank you for agreeing to participate. Your participation is very important to me as we seek to understand how chemistry faculty and graduate students engage in ethical decision-making on issues related to the responsible conduct of research Before we begin, I would like you to take a moment and review the informed consent form. I am providing you with two copies. One that I would like you to sign and return to me and a second that you may keep *Interviewers turn on recorder* |

Directions for Think-Aloud | Your participation today is confidential. Your responses will not be associated with you in any way. All data will be anonymized and analyzed, and reported in aggregate. If at any point you decide that you would like to withdraw from participation, just let me know What we are going to do now is to provide you with a copy of your answers to the online survey you completed. What I want you to do is to work through the survey with me “thinking-out-loud” so that I can understand the reasoning process you used in selecting your answers Please know that this is not a test. Your performance is not being evaluated. There are no right or wrong answers to the survey questions. If you have any questions about the survey questions, if something is unclear, please ask. As you read and work your way through the survey, I would like you to discuss your thoughts and reasoning out loud. Pretend as best as you can that I am not here. Do you have any questions so far? Let’s get started |

Hand out the mentor or protégé interview script | As the participant works through the script, I will prompt, echo, and summarize the participant’s dialog asking questions as needed to capture their thoughts and experience working through the survey. Representative questions might include: Can you tell me what you are thinking? Describe the steps you are going through here |

General questions | After the participant has worked through the survey, I will ask some general questions to gauge the clarity and accuracy of the wording. My conversation with the participant will likely look something like the following: Now that you have worked your way through the interview script, I have several questions I would like to ask you · So, what did you think of the survey and our interview? · Have you participated in any research ethics training as a part of your Ph.D. studies? · How easy or difficult, on a scale of 1–10, ten being most difficult and one being easiest, was it to answer the questions? · What was the easiest scenario to evaluate? Why do you think you found this scenario the easiest? · What scenario was the most challenging to evaluate? Why do you think you found this scenario the most difficult? Based on our earlier discussion, it may be necessary to revisit certain questions. The types of questions and wording I would likely use would look something like this: · I noticed it took you a long time to work through question ____. Can we return to this question and discuss it further? · I noticed question _____ caused some confusion. Can we go back and review the wording of this question so I can improve the wording · I noticed the word __________ caused some confusion, what do you think would be a better word? · Well, that’s the end of the formal part of our think-aloud. I would like to know if you feel that you learned anything by participating in our study. What did you learn? |

Closing Statement | Your comments and insights are very important to me. Once again, I would like to thank you for your time and participation in our study |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Wilson, J. & Mabrouk, P.A. How Do Chemistry Faculty and Graduate Students Engage in Decision Making on Issues Related to Ethical and Responsible Conduct of Research Including Authorship?. Sci Eng Ethics 28, 27 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-022-00381-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-022-00381-6