Abstract

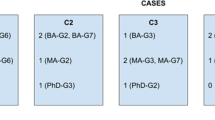

The use of case-based reasoning in teaching professional ethics has come of age. The fields of medicine, engineering, and business all have incorporated ethics case studies into leading textbooks and journal articles, as well as undergraduate and graduate professional ethics courses. The most recent guidelines from the National Institutes of Health recognize case studies and face-to-face discussion as best practices to be included in training programs for the Responsible Conduct of Research. While there is a general consensus that case studies play a central role in the teaching of professional ethics, there is still much to be learned regarding how professionals learn ethics using case-based reasoning. Cases take many forms, and there are a variety of ways to write them and use them in teaching. This paper reports the results of a study designed to investigate one of the issues in teaching case-based ethics: the role of one’s professional knowledge in learning methods of moral reasoning. Using a novel assessment instrument, we compared case studies written and analyzed by three groups of students whom we classified as: (1) Experts in a research domain in bioengineering. (2) Novices in a research domain in bioengineering. (3) The non-research group—students using an engineering domain in which they were interested but had no in-depth knowledge. This study demonstrates that a student’s level of understanding of a professional knowledge domain plays a significant role in learning moral reasoning skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The paper can be obtained by contacting the author Mark Kuczewski directly at <mkuczew@lumc.edu>.

This case, “The Price is Right,” is a modified version of a case with the same name found in the text by Harris et al. (2009, p. 335). Technical issues related to bioengineering were added to that generic engineering ethics case.

This was a preliminary study to the one reported here, which is discussed in detail below.

“Learning and Intelligent Systems: Modeling Learning to Reason with Cases in Engineering Ethics: A Test Domain for Intelligent Assistance,” 1997, National Science Foundation award # 9720341.

Scaffolded Writing and Rewriting in the Discipline (https://sites.google.com/site/swordlrdc/directory, accessed January 29, 2015).

That work was performed under NSF award # 9720341, " Learning and Intelligent Systems: Modeling Learning to Reason with Cases in Engineering Ethics: A Test Domain for Intelligent Assistance", 1997.

The GRE “is a standardized exam used to measure one’s aptitude for abstract thinking in the areas of analytical writing, mathematics and vocabulary” (www.investopedia.com/terms/g/gre.asp). Many graduate schools in the US use these scores to determine an applicant’s eligibility for a given graduate program.

References

Arras, J. D. (1991). Getting down to cases: The revival of casuistry in bioethics. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 16(1), 29–51.

Arras, J., & Rhoden, N. (1989). Ethical issues in modern medicine. Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield Publishing Company.

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2001). Principles of biomedical ethics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brody, B. A. (1988). Life and death decision-making. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brody, B. A. (2003). Taking issue: Pluralism and casuistry in bioethics. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Caplan, A. L. (1980). Ethical engineers need not apply: The state of applied ethics today. Science Technology & Human Value, 5(4), 24–32.

Chambers, T. S. (1995). No Nazis, no space aliens, no slippery slopes and other rules of thumb for clinical ethics. Journal of Medical Humanities, 16(3), 189–200.

Chi, M. T. H. (1978). Knowledge structures and memory development. In R. S. Siegler (Ed.), Children’s thinking: What develops? (pp. 73–96). Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Chi, M. T., & Koeske, R. D. (1983). Network representation of a child’s dinosaur knowledge. Developmental Psychology, 19(1), 29–39.

Churchill, L. (1992). Theories of justice. In C. Kjellstrand & J. B. Dossetor (Eds.), Ethical problems in dialysis and transplantation (pp. 21–31). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Fisher, F. T., & Peterson, P. L. (2001). A tool to measure adaptive expertise in biomedical engineering students. Multimedia Division (Session 2793) In Proceedings for the 2001 ASEE annual conference, June 24–27, Albuquerque, NM.

Goldin, I., Pinkus, R. L., & Ashley, K. D. (2015). Validity and reliability of an instrument for assessing case analysis in bioengineering ethics education. Science and Engineering Ethics,. doi:10.1007/s11948-015-9644-2.

Han, R.-X., Foreman, M., Gollogly, A., Sivarajan, L., & Talman, L. (2007). Interview with Renée C. Fox, Ph.D.: 2007 Lifetime achievement award, American Society for Bioethics and Humanities. Penn Bioethics Journal Vol IV, Issue Fall 2007.

Harris, C. E., Pritchard, M. S., & Rabins, M. J. (2009). Engineering ethics: Concepts and cases. (4th ed.) Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Jonsen, A. R. (1991). Of balloons and bicycles or the relationship between ethical theory and practical judgment. The Hastings Cent Report, 5(21), 14–16.

Jonsen, A. R., & Toulmin, S. (1988). The abuse of casuistry: A history of moral reasoning. Berkley: University of California Press.

Keefer, M., & Ashley, K. D. (2001). Case-based approaches to professional ethics: A systematic comparison of students’ and ethicists’ moral reasoning. Journal of Moral Education, 30(4), 377–398.

Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal. (2007). Call for papers: The method of bioethics. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal., 17(3), 277–278.

Kuczewski, M. (2004). Methods of bioethics: The four principles approach, casuistry, communitarianism. http://bioethics.lumc.edu/about/people/Kuczewski. Accessed December 8, 2009.

Macklin, R. (1993). Teaching bioethics to future healthcare professionals: A case-based clinical model. Bioethics, 7(2–3), 200–206.

Martin, T., Rayne, K., Kemp, N. J., Hart, J., & Diller, K. R. (2005). Teaching for adaptive expertise in biomedical engineering ethics. Science and Engineering Ethics, 11(2), 257–276.

National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2009). Update on the requirement for instruction in the responsible conduct of research. www.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-10-019.html. Accessed January 29, 2015.

National Society of Professional Engineers. (2007). Code of ethics for engineers. http://www.nspe.org/sites/default/files/resources/pdfs/Ethics/CodeofEthics/Code-2007-July.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2015.

Pinkus, R. L., & Gloecker, C. (1999). Want to help students learn engineering ethics? Have them write case studies based on their research/senior design project, Online Ethics Center for Engineering 6/20/2006 National Academy of Engineering. www.onlineethics.org/Education/instructguides/pinkus.aspx. Accessed January 17, 2015.

Pinkus, R. L., Shuman, L. J., Hummon, N. P., & Wolf, H. (1997). Engineering ethics: Balancing cost, risk and schedule: Lessons learned from the space shuttle. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Whitbeck, C. (1995). Teaching ethics to scientists and engineers: Moral agents and moral problems. Science and Engineering Ethics, 1(3), 299–308.

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to acknowledge Kevin Ashley and Ilya Goldin for comments on previous drafts of this paper; Micki Chi for her comprehensive body of work in cognitive psychology that led to the development of the MMR; Michel Ferrari and Judith McQuaide for their contributions to the cognitive modeling grant that is quoted in this paper; Rebecca A. Pinkus and Connor Burn for providing a template of a marking grid that ultimately was developed into our assessment instrument; and Stephanie Bird, who served as a supportive and patient mentor to the first author as this paper and the paper by Ilya Goldin and colleagues (2015) moved from conception to completion. Ann Mertz provided valuable editing for the final version of the paper. Sarah Sudar and Jody Stockdill provided invaluable technical assistance with the completion of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Coding Instructions and Coding Sheet for Student Paper Analysis

Appendix: Coding Instructions and Coding Sheet for Student Paper Analysis

Coding Instructions

In order to achieve the most accurate and consistent classification of respondents’ papers, the same method must be used to code each paper. When reviewing the papers, all coders should follow the instructions below. They will take coders through the assessment form in the order it was meant to be used.

Fill in the classification information at the top of the assessment form according to the attached cover letter.

Analytical Components of Methods of Moral Reasoning

While reading the paper, look for these concepts. Write in the page numbers on the appropriate line next to the concept, noting if the respondent has done one or more of the following: labeled (L), defined (D), or applied (A) the concept. Examples:

-

Label: “Jake was concerned the patient had not given full informed consent.”

-

Define: “A patient gives informed consent if he or she gives permission for a procedure, being fully and completely aware of all it entails and of all consequences. The consent must be freely given and not coerced.”

-

Apply correctly: “After she discussed the procedure with her doctor and had her questions answered, Emily freely agreed to have the operation done.”

The attached glossary provides definitions and examples of all the concepts. Use it as a guide in coding. It should be particularly useful in the following two cases: (1) respondents may apply a concept without explicitly labeling it (as shown in the above example) or (2) if you find that there is a serious error in the respondent’s definition or application of the concept. In the latter case, please make a note in the margin. For example: “L, D, informed consent. Incorrect D: the student discusses informing the patient, but does not discuss the meaning of consent.”

If the paper contains a concept not on the list, then add it to the open spaces on the concept checklist.

Higher Order Criteria (Bottom of the Assessment Form)

The criteria listed here capture more abstract aspects of the ethical analysis. Use of these criteria can be indicated with a simple yes or no, but the coder should also provide a brief justification and page number(s) of when the criterion was used.

-

Professional knowledge means that the case is set in the context of well articulated and relevant technical knowledge.

-

Identify different perspectives means that the respondent has analyzed the case from different points of view.

-

Moving flexibly among various perspectives suggests that the person has a deep knowledge of the different perspectives and can use these different domains as they analyze the case. A paper exhibits this by not only analyzing the case from the viewpoints of various case participants but also by explaining how these viewpoints and analyses relate to one another and to the overall ethical analysis.

-

An analogous case can be a separate case cited for comparison. It can also be evident when a student changes the facts of the case, i.e. “What if the subject was your mother?”

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pinkus, R.L., Gloeckner, C. & Fortunato, A. The Role of Professional Knowledge in Case-Based Reasoning in Practical Ethics. Sci Eng Ethics 21, 767–787 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9645-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9645-1