Abstract

Purpose of the review

The introduction of H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) into clinical practice has been a real breakthrough in the treatment of acid-related diseases. PPIs are now the standard of care for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcer disease (PUD), Helicobacter pylori infection, NSAID-associated gastroduodenal lesions, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). However, despite their effectiveness, PPIs display some intrinsic limitations, which underlie the unmet clinical needs that have been identified over the past decades.

Recent findings

To address these needs, new long-acting compounds (such as tenatoprazole and AGN 201904-Z) and new PPI formulations, including instant release omeprazole (IR-omeprazole) and dexlansoprazole modified release (MR), have been developed. However, a major advance has been the development of the potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs), which block the K+,H+-ATPase potassium channel, are food independent, are reversible, have a rapid onset of action, and maintain a prolonged and consistent elevation of intragastric pH. Vonoprazan and tegoprazan are the two marketed P-CABs while two other compounds (namely fexuprazan and X842) are under active development. Available for almost 6 years now, a considerable experience has been accumulated with vonoprazan, the efficacy and safety of which are detailed in this paper, together with the preliminary results of the other members of this new pharmacologic class.

Summary

Based on the available evidence, erosive reflux disease, H. pylori infection, and secondary prevention of NSAID gastropathy can be considered established indications for vonoprazan and are being explored for tegoprazan and fexuprazan. In the treatment of severe (LA C & D) reflux esophagitis and H. pylori eradication, vonoprazan proved to be superior to PPIs. Other uses of P-CABs are being evaluated, but clinical data are not yet sufficient to allow a definitive answer on its efficacy and possible superiority over the current standard of care (i.e., PPIs). The most notable indication of upper GI (non-variceal) bleeding, where vonoprazan would prove superior to PPIs, has not yet been explored. The safety of P-CABs in the short-term overlaps that of PPIs, but data from long-term treatment are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The advent of antisecretory drugs, such as H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), has revolutionized the management of acid-related diseases, leading to the virtual abolition of elective surgery for ulcer disease and relegating anti-reflux surgery to patients with reflux disease not adequately managed by medical therapy. Acid suppression with delayed-release PPIs (DR-PPIs) has remained the cornerstone of medical treatment of GERD and its complications [1, 2••, 3], despite evidence for almost 20 years that they have some shortcomings [4, 5]. New more effective compounds have been developed [4, 6••, 7,8,9], which have an extended duration of acid suppression that can exert additional benefits [10, 11]. Some of these new drugs provide a significant advance over current treatments [12]. Novel PPIs have been synthesized, but few reached clinical testing. Tenatoprazole (a non-benzimidazole derivative) and AGN a 201904-Z (an omeprazole pro-drug, also known as Durasec™) display a half-life longer than that of current PPIs (about 9 and 4 h, respectively, versus 1.5–2.0 h) and show a superior control of intragastric acidity during nighttime, with few episodes of nocturnal acid breakthrough (NAB) [13, 14]. Only two alternative formulations of existing drugs, instant release omeprazole (IR-omeprazole) and modified-release dexlansoprazole (MR-dexlansoprazole), have been introduced in some countries [11]. These represent a measurable but small incremental advance in the pharmacological control of acid secretion over the DR-PPIs but fall short of achieving the ideal pharmacologic profile, considered desirable to control acidity in patients with more complex clinical problems [13].

An innovative approach has been the introduction of the of H+,K+-ATPase blockers, called potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs) [15,16,17], which block the K+ exchange channel of the proton pump, resulting in a very fast, competitive, reversible inhibition of acid secretion. A P-CAB offers a very rapid and greater elevation of intragastric pH than a DR-PPI, while maintaining a similar or greater degree of antisecretory effect, with a duration which is dependent on the drug half-life. This class of antisecretory compounds has attracted several Pharmaceutical Companies to this avenue of drug development. Some new compounds are already in clinical use in Asian countries as well as in South America and are currently being evaluated for use in North America and Europe. Some others are under active clinical development.

The aims of this review are to summarize the relevant pharmacologic properties of P-CABs together with the current unmet clinical needs in acid-related diseases and discuss how this new class of antisecretory drugs can address these needs.

P-CABs: chemistry and pharmacology

Conversely from the current PPIs, which are all substituted benzimidazoles, P-CABs belong to different chemical classes (Table 1). Although sharing the same mechanism of action, they represent a heterogeneous class of drugs. P-CABs are lipophilic, weak bases that have high pKa values and are stable at low pH. This combination of properties allows them to concentrate in acidic environments. For example, the concentration of a P-CAB with a pKa of 6.0 would theoretically be expected to be 100,000-fold higher in the parietal cell canaliculus (pH = 1) than in the plasma (pH = 7.4) [12].

Almost all these new compounds display rapid and effective antisecretory activity, but not all favorable pharmacodynamic properties have translated into clinical benefits. This is the case for revaprazan (YH1885) [18] and linaprazan (AZD0865) [13], which failed to show superiority over standard-dose PPIs in healing peptic ulcer or reflux esophagitis, respectively.

Conversely from earlier compounds, vonoprazan (TAK-438), a novel and potent orally active P-CAB [19] (developed by Takeda and brought to phase 3 in USA and Europe by Phathom), does represent a real breakthrough in acid suppression. The drug is a pyrrole derivative, displaying the most powerful inhibition of the proton pump compared to PPIs and other P-CABs (Fig. 1) [20].

Vonoprazan: chemical structure of vonoprazan and comparative inhibitory potency (expressed as IC50) towards Hog K+,H+-ATPase in vitro (from Shin et al. [20])

Vonoprazan has been in clinical use for almost 6 years and considerable clinical data have now been accumulated and are detailed in several extensive reviews [19, 21•, 22,23,24,25, 26•]. Its peculiar pharmacological properties can be summarized as follows [6••]:

-

In contrast to DR-PPIs, which are acid-labile drugs, vonoprazan is stable in the acidic gastric environment.

-

The drug has good solubility both in acidic and in neutral conditions.

-

Vonoprazan exerts a pH-independent and direct inhibitory activity on H+/K+-ATPase, without need for conversion into an active form

-

Its dissociation rate from the proton pump is slow and its retention time in the gastric mucosa long (24 h or more).

-

As a consequence, vonoprazan acid inhibitory activity is prolonged.

Clinical pharmacology investigations [27] have been performed in Japanese or Caucasian healthy male volunteers. These studies showed that vonoprazan has almost linear pharmacokinetics and shows a dose-dependent inhibition of 24-h acid secretion (87% and 92% respectively). With vonoprazan 40 mg once daily, the nighttime period (from 20:00 to 08:00) spent above pH 4 and above pH 5 was 100% and 99%, respectively, in Japanese subjects and 90 and 79%, respectively, in UK volunteers. Both the 24-h and nocturnal pH > 4 holding times showed a linear correlation with the AUC [6••]. As consequence of the increase in intragastric pH, serum gastrin and pepsinogen I concentrations also increased in a dose-dependent fashion. Vonoprazan was well tolerated at all doses studied and there were no changes in liver enzymes. A subsequent investigation [28] studied acid inhibition after repeated administration and found that, after 7 days of treatment, the mean 24-h intragastric pH > 4 holding time with vonoprazan 40 mg daily was 100% and 93.2% in Japanese subjects and UK volunteers, respectively, while mean nocturnal times spent with pH > 4 were 100% and 90.4%. In contrast to esomeprazole (and other PPIs), the antisecretory activity of vonoprazan was not dependent on the CYP2C19 genotype [29]. When compared with a PPI (lansoprazole, 30 mg) or an H2RA (famotidine, 20 mg) in H. pylori-negative healthy volunteers, the rise of intragastric pH with vonoprazan (20 mg) was higher and faster [30]. The acid inhibitory effect of vonoprazan (20 mg) was also more rapid and sustained than that of esomeprazole (20 mg) or rabeprazole (10 mg) in patients, who were CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers. Moreover, virtually no episodes of NAB were evident after administration of vonoprazan [31].

Tegoprazan (formerly RQ-00000004 or CJ-12420) is a new P-CAB, recently approved in South Korea for treatment of GERD and PUD. It is a benzimidazole derivative [32, 33], which was developed by RaQualia Pharma in Japan and brought to phase 3 by CJ HealthCare in Korea. A human volunteer study [34] found that single oral administration of the drug under fasted conditions increased intragastric pH to > 6. In a further study with single and multiple doses of tegoprazan [35], a linear PK profile was observed, which was accompanied by a rapid dose-dependent suppression of acid secretion. In the same study, drug bioavailability was estimated to be 86–100%, the compound being mostly eliminated through the stool, with urinary excretion limited to 3–6% [35].

Fexuprazan (DWP14012) is a pyrrole derivative, developed by Daewoong [36], which is currently in Phase III development in South Korea and China. Single (10–320 mg) and multiple (20–160 mg) ascending, once-daily-dose studies with this compound were performed on healthy male subjects without H. pylori infection [37]. Fexuprazan showed rapid and sustained, dose-dependent suppression of gastric acid secretion for 24 h after both single and multiple oral administrations. Although after single doses PK was not linear, plasma concentrations of fexuprazan increased in a dose-proportional manner after multiple doses, without evidence of accumulation in plasma. The drug was well tolerated, with no evidence of hepatotoxicity [37].

One of the drawbacks of PPIs is that they are subject to liver catabolism, mainly by cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19), a drug-metabolizing enzyme for which a genetic polymorphism exists. As a consequence, there are interindividual variations in the PK and PD of PPIs [6••]. Their efficacy in acid-related diseases (especially GERD and H. pylori eradication) is in fact dependent on CYP2C19 genotype [2••]. The new P-CAB class of drugs is devoid of such limitation. Indeed, although different members of this class have been studied mainly in Asian patients [38], vonoprazan was found to provide a similar acid suppression in both Asians and Caucasians [28]. Fitting well with the requirements of the ICH E17 guideline [39], gastric acid suppression by fexuprazan was similar among Koreans, Caucasians, and Japanese, and PK, PK-PD relationship as well as safety were also similar among the three different ethnic groups [40].

X842 is a pro-drug of linaprazan, which has been studied in several phase I studies and 2 phase II trials, performed on almost 3,000 patients. In these investigations, the X842 active metabolite (linaprazan) was well tolerated, with a rapid and effective acid inhibition. Since its half-life is relatively short, the drug was unable to control nocturnal acid secretion [41]. On the contrary, X842 provides effective 24-h pH control through its longer half-life.

The first human study of X842 [42], which is being developed in Europe by Cinclus Pharma AG, showed that—following doses of 1 mg/kg or higher—linaprazan rapidly appears in plasma, with the Cmax at ~ 2 h after oral administration and has a half-life ≥ 10 h. PK appears to be linear since AUC is correlated with the X842 dose. Acid inhibition over the 24 h was dose-dependent, and plasma concentrations of the active metabolite (i.e., linaprazan) were linearly correlated with intragastric pH. With doses of X842 of 2 mg/kg, effective 24 h acid control is achieved, without NAB. A phase 2 study in patients with severe esophagitis is underway and the start of phase III trials is planned for 2021.

A synopsis of the PK and PD characteristics of the current P-CABs [38], given as a single morning dose to healthy H. pylori-negative Asian subjects, is shown—in comparison with esomeprazole—in Table 2.

Acid suppression in GERD

PPI efficacy and unmet needs

The pathogenesis of GERD is complex and multifactorial but with a predominant neuro-motility component [3]. Abnormal esophageal acid exposure is not the result of gastric acid hypersecretion, which has been demonstrated in only a subset of GERD patients [43]. Despite this, antisecretory drugs (H2RAs and PPIs) remain the mainstay of medical treatment for GERD. They act indirectly by reducing the volume and concentration of gastric secretion available for reflux, thus lessening the aggressive power of the refluxed material [12, 44]. PPIs also reduce the size of the acid pocket and increase the pH (from 1 to 4) of its content [45]. The clinical efficacy of these drugs has been clearly shown in many studies and the superiority of PPIs over H2RAs has been established beyond doubt [1, 2••, 46]. Eight-week therapy with standard (once daily) dose PPIs can achieve healing of reflux esophagitis in more than 80% of patients [47], a rate depending on the severity of mucosal lesions [48, 49]. This healing rate can be further improved by increasing the PPI dose to twice daily dosing (morning and evening, NNT = 25) [47]. PPIs relieve typical symptoms in patients with either erosive or non-erosive disease [50]. However, regurgitation is much less reduced than heartburn [51]. Although in the past PPIs were considered to be less efficacious in NERD, this belief has been dismissed by a meta-analysis [52], which has shown that in true NERD patients, whose diagnosis was confirmed by pH metry or pH impedance recording, the symptom response after PPI treatment is similar to that achieved in patients with erosive reflux esophagitis.

Although not as frequent as previously suggested, PPI-refractory heartburn, occurring more commonly in NERD than in erosive disease, does exist. A careful post hoc analysis of 5796 patients from 4 esomeprazole RCTs found that some 20% PPI-treated patients had a partial response [53]. However, outside clinical trials, in every day clinical practice, the prevalence is higher, reaching 54.1% in the last published survey [54]. Although a standard PPI dose can occasionally control symptoms, nocturnal intragastric acidity often remains high, with NAB in these patients. A split regimen (either standard or double dose) of a PPI, given twice daily (before breakfast and before the evening meal), provides superior acid control. In patients with persistent nocturnal symptoms, the addition of an H2RA at bedtime may be indicated to control NAB and associated esophageal acidification [10, 55,56,57], despite the likely development of tolerance [58]. Although management options have been recommended by an expert panel for patients with persistent symptoms while on PPIs [59••], refractory GERD is still one of the unmet clinical needs, which also include the need for a significant improvement in symptom control and faster assured healing, especially in patients with grade C and D erosive esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and extra-esophageal manifestations of GER [4, 7, 8, 10, 60, 61].

Vonoprazan efficacy in erosive reflux disease

As predicted by a large meta-analysis evaluating the intragastric pH data of the currently used antisecretory regimens [62], the healing rate of reflux esophagitis after 8-week therapy with vonoprazan was almost 100%. Moreover, while there were no differences between vonoprazan (20 mg daily) and lansoprazole (30 mg daily) in grade A and B esophagitis, the healing rate with vonoprazan was significantly higher than that with lansoprazole in grade C and D esophagitis [63], a superiority maintained in CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers [64]. The superiority of vonoprazan over lansoprazole in healing severe esophagitis was confirmed in a recent, large, multicenter clinical trial, including 468 Asian patients [65]. Vonoprazan is also effective in patients with PPI-resistant esophagitis, inducing healing in some 85% [66, 67]. The efficacy of vonoprazan was maintained long term, with post hoc analysis showing lower recurrence rates compared to lansoprazole both in Japan [68] and in other Asian (i.e., China, Malaysia, South Korea, and Taiwan) countries [69].

Despite a better healing efficacy, symptom relief with vonoprazan (20 mg daily) in patients with GERD was not different from that achieved with esomeprazole (20 mg daily) [70]. However, symptom relief with vonoprazan appeared more quickly. In patients with esophagitis, heartburn was relieved earlier with vonoprazan compared with lansoprazole. On day 1, complete relief was achieved in 31.3% and 12.5% of patients, taking vonoprazan and lansoprazole, respectively. In addition, significantly more patients attained complete nocturnal heartburn relief with vonoprazan than with lansoprazole [71]. In patients with esophagitis and persistent symptoms after 8 weeks of appropriate PPI therapy [55, 72], switching to vonoprazan (20 mg once daily) provides more potent and prolonged gastric acid suppression, more effective control of esophageal exposure to acid, enhanced symptom improvement, and faster healing of mucosal lesions [73].

While another meta-analysis is ongoing [74], a systematic review and meta-analysis [75], including 6 eligible RCTs comparing the efficacy and safety of vonoprazan with PPIs for GERD, has recently been published. Results show that vonoprazan is non-inferior to PPIs as therapy for patients with GERD (RR: 1.06–95% C.I. 0.99–1.13). However, subgroup analysis indicates that vonoprazan is more effective than PPIs for patients with severe erosive esophagitis (RR: 1.14–95% C.I. 1.06–1.22). The safety outcomes for vonoprazan are similar to those for PPIs (RR: 1.08–95% C.I. 0.96–1.22). In addition to pairwise comparisons, two network meta-analyses are available [76, 77]. The first [76] shows that GERD healing with vonoprazan is higher than with rabeprazole (20 mg) but not higher than other PPIs. However, subgroup analysis indicates that vonoprazan is more effective than most PPIs for patients with severe erosive esophagitis. In the second network meta-analysis [77], which was devoted to maintenance of healing, the efficacy of vonoprazan appears to be higher than that of some PPIs. However, a direct comparison of vonoprazan to each PPI is required to confirm these findings.

Vonoprazan efficacy in non-erosive reflux disease

In a placebo-controlled, multicenter RCT in patients with NERD [78], the number of heartburn-free days, when taking vonoprazan (10 mg or 20 mg daily), was no better than placebo, although the mean severity of heartburn score was lower. In a long-term study [79] in GERD patients taking vonoprazan (10 mg daily), 89% experienced symptom relief at 1 month while 81.6% reported a sustained improvement at 1 year. Of the 18.4% who relapsed, most were controlled by a dose increase. When taken on demand by patients with NERD, vonoprazan (20 mg) was equivalent to PPI maintenance therapy in controlling symptoms [80]. Moreover, vonoprazan was also effective in patients with PPI-resistant NERD. A small retrospective study [81] found that 69.2% of patients reported an improvement in symptoms and quality of life as measured by the GERD-Q score, probably through a more effective reduction of esophageal acid exposure [73]. The effect of low-dose (10 mg) vonoprazan on GI symptoms in patients with GERD was studied in patients with erosive or non-erosive disease [82]. Together with typical symptoms, also epigastric pain (73%), postprandial distress (60%), constipation (58%), and diarrhea (52%) were improved by P-CAB treatment. However, improvement or resolution of GERD symptoms in patients with erosive esophagitis was higher than that in those with NERD (91% versus 83%, p = 0.260 and 71% versus 47%, p = 0.025, respectively) [82].

It is important to appreciate that P-CAB-resistant NERD is also reported and is ascribed to weakly acidic reflux or more likely to functional heartburn [83]. This apparent resistance, however, could be dose-dependent. A retrospective, small study [84] evaluated NERD patients with symptoms resistant to double-dose PPIs, who were switched to vonoprazan (20 mg daily). pH impedance recording revealed fewer reflux events at pH < 5 in patients with symptom improvement compared to those without. In these patients, the proportion of reflux at pH < 4 decreased but that of reflux at pH 4–5 increased while that of reflux at pH < 5 did not change [84]. Despite the limitations of the study, the results suggest that the lack of symptom improvement is related to inadequate acid suppression that could be addressed by a higher vonoprazan dose.

A recent study [85] evaluated pH impedance and HRM parameters in patients with GERD symptoms resistant to PPI or vonoprazan. There was a significant difference in the proportion of underlying conditions between the two groups of patients. After excluding esophageal motor disorders, no cases of acid-related GERD (including erosive esophagitis and NERD) were observed in the vonoprazan-resistant GERD group [85]. These findings suggest that vonoprazan could be used as a diagnostic tool to rule out acid-related GERD.

Is there a role for vonoprazan in Barrett’s esophagus?

Continuous acid suppression with PPIs is indicated in patients with Barrett’s esophagus of any mucosal length because of their potential chemopreventive activity against neoplastic transformation [86], a property advocated by the ACG [87] and AGA [88] but denied in the BSG guidelines [89]. Indeed, a meta-analysis of observational studies showed that PPI use is associated with a 71% reduction in risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma and/or high-grade dysplasia in this patient population (adjusted OR 0.29) [90]. Despite a contrary opinion of the AGA [88], current evidence suggests that standard PPI treatment is unable to normalize esophageal exposure to acid in the vast majority of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Profound (and likely individually tailored) maximal acid suppression is needed not only to control GER, but also in the hope of achieving a better chemopreventive effect [91]. In this connection, the recently published results of the AspECT trial [92•] showed that high-dose PPI therapy (80 mg esomeprazole daily) prolonged time to the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, esophageal adenocarcinoma, and high-grade dysplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus compared with low-dose PPI (20 mg daily). The profound and extended (during both daytime and nighttime) antisecretory effect of vonoprazan could well be especially useful in the long-term treatment of patients with Barrett’s esophagus and data concerning its use in this precancerous condition are eagerly awaited.

Vonoprazan for GERD: conclusions

P-CABs clearly overcome many of the drawbacks and limitations of the DR-PPIs. In acid-related disorders, mucosal healing is directly related to the degree and duration of acid suppression and the length of treatment [10, 62, 93, 94]. Considering the difficulties encountered in attaining effective symptomatic control, particularly at night, using currently available DR-PPIs once daily, this new class of drugs achieves rapid, potent, and prolonged acid suppression and offers the chance of addressing many of the unmet clinical needs in GERD [4, 7, 8, 10], such as the need for fast and assured healing of severe reflux esophagitis and achieving rapid heartburn relief.

It is well known that more severe or rapidly recurring esophagitis is associated with acidification of the esophagus and an increased acid dwell-time as a consequence of lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction [95]. This leads to a fall in intra-esophageal pH, especially at night, related to the duration of and the degree of drop in intragastric pH holding time below pH 4 [62]. Along the same lines, several studies have reported that weakly acidic reflux is one of the most relevant underlying causes of PPI-refractory NERD (for review see [96]). In addition, it was shown that the reflux events at pH 4–5, reaching the proximal esophagus, were the main symptom trigger in these patients [97]. Indeed, the pH of weakly acidic reflux represents a determining factor in provoking heartburn [98]. All these findings suggest that—in patients with more severe esophagitis or PPI-refractory disease—the choice of a P-CAB is appropriate. The available data with vonoprazan are consistent with this idea.

A few clinical studies have suggested that treatment of GERD with a P-CAB is conferring only a small advantage. It is helpful therefore to have a single study from Japan which provides a cost-effectiveness analysis, comparing vonoprazan with lansoprazole in the initial treatment of reflux esophagitis [99]. The author provided a clinical decision analysis, using a Markov model to compare the P-CAB with the current treatment guideline, which recommends a standard-dose PPI, lansoprazole 30 mg once daily, for 8 weeks for the initial treatment of GERD. The model considered treatment of endoscopically confirmed, uncomplicated reflux esophagitis. The comparison evaluated vonoprazan (20 mg once daily for 4 weeks) in a decision tree, which considered extending treatment to 8 weeks, and how retreatment could be approached on recurrence. The P-CAB strategy was superior to PPI in cost per patient to achieve the predetermined clinical outcome and number of days for which medication was required. The superior outcome in favor of the P-CAB was robust in sensitivity analyses, even when healing rates in mild esophagitis were considered.

Preliminary data on tegoprazan and fexuprazan efficacy in GERD

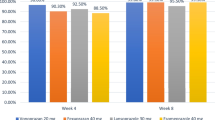

The efficacy of tegoprazan, a P-CAB with a benzimidazole structure [32, 33] and an antisecretory activity similar to that of vonoprazan [38], was recently evaluated in patients with reflux esophagitis. In the study, 302 patients with mucosal breaks were randomized to tegoprazan (50 mg or 100 mg daily) or esomeprazole (40 mg daily), where healing rates after 4 weeks treatment were 91.3%, 93.4%, and 94.3% in the three groups, respectively, while the rate after 8 weeks was 98.9% in all groups [100]. The groups all showed similar improvement, although numbers were too small to allow proper interpretation of results in more severe (grades C and D) esophagitis. The drug provided also a symptomatic benefit, with significant improvement in reflux disease questionnaire and GERD Health Related Quality of Life scores [100].

Fexuprazan, a pyrrole derivative [36] with a rapid and complete onset of antisecretory activity [38], was investigated in a phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial. Two hundred and sixty adult patients with endoscopically confirmed erosive esophagitis (LA grades A to D) were randomized to receive this P-CAB (40 mg once daily) or esomeprazole (40 mg once daily) [101]. The primary outcome measure was the cumulative proportion of patients with healed mucosal breaks, confirmed by endoscopy, at week 8. Healing rate at week 4, symptoms, and quality of life were also assessed. Fexuprazan was non-inferior to esomeprazole, with identical (i.e., 99.1%) cumulative healing rates at 8 weeks and similar rates (90.3% and 88.5%, respectively) at 4 weeks. However, fexuprazan showed better symptom relief in patients with moderate to severe heartburn, an effect persisting also during night time. A similar benefit was evident also for cough. The drug was well tolerated, with an incidence of adverse events comparable between treatment groups [101].

Eosinophilic esophagitis: a role for vonoprazan?

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an eosinophil-rich, Th2 antigen-mediated disease of increasing, worldwide prevalence. Symptoms reflect esophageal dysfunction, and characteristic endoscopic appearances consist of rings, furrows, exudates, and edema. Progressive disease leads to pathologic tissue remodeling, with ensuing esophageal rigidity and loss of luminal diameter caused by strictures [102]. Until recently, patients with esophageal eosinophilia responding to PPIs (PPI-REE) were excluded from the EoE spectrum [103]. Given the fact that EoE and PPI-REE are indistinguishable even at the histological, molecular, and genetic level, the last European guideline has included PPI-REE in the spectrum of the disease [104].

It is well known that PPIs display several non-antisecretory activities, of which the mucosal protective and anti-inflammatory ones are the most relevant in the treatment of EoE [86]. There are several mechanisms underlying the anti-inflammatory action of this class of drugs, including anti-oxidant effects and effects on inflammatory cells, and endothelial and epithelial cells as well as on gut microbiota. In vitro and in vivo studies suggest that the anti-inflammatory effects of PPI treatment rather than acid suppression alone may be responsible for the observed clinical and histologic improvement through inhibition of the Th2-allergic pathway [86]. Indeed, like topical corticosteroids, PPIs downregulate cytokine expression [105].

Several retrospective and prospective studies have reported histological remission and symptom improvement (even with persistent eosinophilic infiltration) after an 8-week treatment course with PPIs, with established GERD having a higher chance of responding to PPIs (for review see [102]). A meta-analysis of 33 studies, including 619 patients (431 adults and 188 children) found an overall histologic remission and clinical response of 50.5% and 60.8%, respectively [106]. No differences were observed regarding the study population, the type of publication, or its quality. Due to their safety profile, ease of administration, and high response rates (up to 60% clinically), PPIs have been considered a first-line pharmacologic treatment for EoE [2••]. Not all patients with EoE respond, however, to PPI therapy [104, 107].

In a Japanese study on EoE, vonoprazan (20 mg once daily) provided a clinical and histologic efficacy similar to that seen with esomeprazole or rabeprazole (Table 3) [108]. It was also reported that half of the EoE patients, who were PPI-resistant, did respond to P-CAB therapy [109]. Clearly, randomized, prospective trials (also outside Asia) are needed to confirm these findings. Whether P-CABs share with PPIs any of the antinflammatory effects (which likely underlie PPI efficacy in EoE) is currently unknown, although an antinflammatory activity of tegoprazan in a mouse model of experimental colitis has recently been reported [110].

Acid suppression for eradication of the Helicobacter pylori infection

Current treatments and unmet needs

Despite a definite trend of decreasing H. pylori infection prevalence in the western world [111], the global prevalence of the infection remains high with an estimate of 4.4 billion people infected worldwide [112]. Although the great majority of patients with H. pylori infection will not have any clinically significant complications, the gastric colonization with this microorganism is a cofactor in the development of three important upper gastrointestinal diseases: duodenal or gastric ulcers, gastric cancer, and gastric mucosa–associated lymphoid-tissue (MALT) lymphoma, with a risk for developing these conditions that varies widely among populations [113, 114••]. In all patients referred for clinical symptoms related to the upper gastrointestinal tract, proper investigation and diagnosis should always include the assessment of H. pylori infection, which—depending on the clinical scenario—will be based on invasive or non-invasive testing [115]. Both the Maastricht V/Florence [116••] and Kyoto Global [117] Consensus have established that—being an infectious disease—H. pylori gastritis should be cured, even in the absence of symptoms and irrespective of the presence of complications. Besides the established indications (in which causality and therapeutic effects are proven), eradication is also indicated in other conditions (including idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, vitamin B12 deficiency, iron-deficiency anemia), where therapeutic benefit has been shown although causality has not yet been proven [115].

Several international guidelines and consensus conferences [116, 118,119,120,121,122] have given recommendations, regularly revised and updated, to optimize the clinical management of H. pylori infection. The survival capabilities of H. pylori within the stomach make eradication difficult. Since no single therapy is effective, several different drug combinations have been developed, with variable and often inconsistent success [123]. The search for an ideal regimen to treat H. pylori infection still continues [124].

After the early observation of the efficacy of bismuth compounds [125], which were re-discovered later on [126], all subsequent regimens (be they dual, triple, sequential, or quadruple) included a PPI (Table 4) [127]. As shown by the MACH-2 trial [128], PPIs are an essential component of any eradication regimen (Table 3). They indeed display several pharmacological actions that give them a place in the eradication regimens [129]. While the use of an antisecretory drug together with antibiotic(s) is logical for the treatment of peptic ulcer, the combination of PPIs with antimicrobials was put forward by a thoughtful editorial [130••], detailing the potential mechanisms underlying this drug synergy.

To be most effective, full-dose PPIs should be given twice daily, concomitantly with antimicrobials as the mean intention-to-treat (ITT) cure rates are greater in patients who use the high-dose PPI, compared with the standard-dose regimen [2••]. The importance of the degree of acid suppression on the eradication efficacy became apparent when attempting a dual (namely omeprazole-amoxicillin combination) therapy. Indeed, a linear relationship between omeprazole dose (20–120 mg daily) and eradication rate was clearly evident: the higher the PPI dose (and, as a consequence, acid suppression), the higher eradication rate [131].

Resistance of H. pylori to antibiotics has reached alarming levels worldwide [132] and has a great effect on efficacy of treatments [133]. Indeed, while drug, dose, formulation, and duration of treatment are all important factors, resistance to antimicrobials as well as the selected antisecretory regimen remains the most critical factor influencing the global eradication rate [134]. Primary resistance can significantly impair the efficacy of eradication regimens, especially those including macrolides (like clarithromycin). Resistance to fluoroquinolones (such as levofloxacin) can also impair the efficacy of eradication regimen. However, resistance to nitroimidazole could be partially overcome in vivo [133, 135]. To deal with the problem of antimicrobial resistance, several new therapies have been developed. Together with the number of drugs, the number and complexity of the regimens have also increased, with a consequent decrease in compliance to treatment, which often compromises efficacy [136].

Strong and long-lasting acid inhibition, especially during the nighttime period, is of pivotal importance for successful H. pylori eradication [130, 137]. This has been outlined by two Asian trials showing that the intragastric pH and the time spent below pH 4 were significantly higher and longer, respectively, in patients cured of H. pylori infection compared to those who remained infected [138, 139]. Moreover, patients with episodes of NAB had eradication rates lower than those without NAB [138].

Drugs providing effective control of both daytime and nighttime acid secretion will likely show better compliance. Indeed, the available DR-PPIs should be given in high dose and at least twice daily, while long-acting antisecretory compounds can be confidently prescribed once daily, leading to a simpler regimen while maintaining the same efficacy. Last but not least, the use of a drug, endowed with an extended duration of acid inhibition, may increase the opportunity to achieve high eradication rates even with dual therapy (e.g., amoxicillin/acid suppressing drug) [140, 141].

Efficacy of vonoprazan-based eradication regimens

An early meta-analysis [142], including 10 studies and 10,644 patients, showed that vonoprazan-based triple therapy was superior to PPI-based triple therapy, with comparable tolerability and adverse events. This superiority was only evident in first-line H. pylori triple eradication therapies but not in second-line treatments [143]. However, a more recent systematic review with meta-analysis [144], specifically devoted to the topic and including 16 comparative studies, concluded that a vonoprazan-based H. pylori eradication regimen can be the first choice for second-line treatment. Moreover, an additional meta-analysis [145] pointed out that vonoprazan is superior to conventional PPIs only for eradication of clarithromycin-resistant H. pylori strains while vonoprazan-based and conventional PPI-based therapies are similarly effective in patients harboring clarithromycin-susceptible H. pylori strains. Finally, a retrospective study [146] found that vonoprazan-based triple therapy was effective as susceptibility-guided triple therapy for H. pylori eradication.

The majority of Japanese studies have been performed with vonoprazan-based or PPI-based triple therapy regimen (i.e., with amoxicillin and clarithromycin) since only triple therapy combinations are currently covered by the Japanese National Health Insurance System [147]. The effectiveness and safety of vonoprazan-based triple therapies in Japan has recently been reviewed [148]. In routine clinical practice, the eradication rates of the first-line therapy and the second-line therapy were 91.24% and 95.45%, respectively. However, as a consequence of the constant increase in clarithromycin resistance, a progressive decrease in the effectiveness of vonoprazan triple regimens becomes evident [143]. Post-marketing surveillance did not show any new safety concerns and incidence of adverse drug reactions with vonoprazan-based regimens ranged from 1.89 to 3.22% [148]. Studies with vonoprazan-based alternative regimens will provide a better understanding of the efficacy of vonoprazan in the eradication of H. pylori. In this respect, some recent studies evaluated vonoprazan-based dual therapies.

After the original report of Miehlke et al. [131], several investigators studied both standard- and high-dose PPI combinations with amoxicillin in the hope of finding an effective and simple eradication regimen. While the standard-dose PPI-amoxicillin dual therapy gave disappointing eradication rates (for review, see [149]), stronger and long-lasting acid suppression (achieved with multiple doses of the antisecretory drug) appeared to be successful. Three meta-analyses [150,151,152] collected all the studies with high-dose PPI-amoxicillin combinations, which showed that this dual therapy is as effective as triple or bismuth-based quadruple therapy, either in first-line or rescue treatment. In addition, compliance with dual therapy was better and the adverse event rate lower [150,151,152].

The antisecretory effect of vonoprazan is long-lasting, covering both daytime and nighttime periods. A twice-daily dose of vonoprazan could, therefore, be sufficient to synergize with amoxicillin, thus further enhancing patient compliance compared with current high-dose PPI dual regimens. Indeed, when vonoprazan-based triple therapy is given to patients harboring clarithromycin-resistant strains, it is like giving a dual therapy and the superiority of vonoprazan triple therapy over PPI triple therapy [145] is likely due to a superior pharmacologic synergy between the P-CAB and the amoxicillin component compared to a standard DR-PPI-amoxicillin combination. Available studies [153,154,155,156,157], summarized in Table 5, and a meta-analysis of them [158] confirm this. A pooled eradication rate of 85.6% (95% CI: 74.8 to 94.0) was found, albeit with evidence of significant heterogeneity (I2 = 64.8%). The eradication rate in patients, who harbored clarithromycin-resistant strains, was 95.4% (95% CI: 86.6 to 100). A comparison of this dual therapy with the pooled data from FDA-approved eradication regimens showed that it provides better eradication rates than PPI or rifabutin triple therapies as well as comparable efficacy to the bismuth quadruple therapy [159]. The overall rate of adverse events with dual therapy was 26.5% (95% CI: 20.0 to 33.5), a figure not dissimilar from that with triple therapies but lower than the rate observed with bismuth quadruple therapy or Talicia™. Provided these results are confirmed in large clinical trials outside Asia, the vonoprazan-amoxicillin dual therapy may become a simple, first-line regimen for the eradication of H. pylori infection. Before being largely adopted, this dual therapy should be optimized, by selecting the best dose, number of drug administrations, and duration [26•].

The WHO listed Helicobacter pylori among 16 antibiotic-resistant bacteria that pose the greatest threat to human health [160]. Given the alarmingly high H. pylori antibiotic resistance rates, antibiotic stewardship programs need to be developed and implemented. In this regard, a move to dual therapy—by using only one antimicrobial agent—will fit well to support this endeavor.

Acid suppression for NSAID-associated GI mucosal injury

Current treatments and unmet needs

Musculoskeletal pain is common and disabling, especially in the elderly population, whose number and proportion is estimated to double by 2030, compared to the 2000 figure [161]. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), indicated for the treatment of inflammatory pain, is therefore bound to increase. NSAIDs are very effective drugs, but their use is associated with a broad spectrum of adverse reactions involving the liver, kidney, CV system, skin, and gut, with gastrointestinal (GI) untoward effects being the most common [162].

NSAIDs and aspirin can damage the upper GI tract, by impairing almost all the mucosal mechanisms of defense, resulting in a mucosa which is unable to tolerate even a low acid load. NSAID-associated injury is pH-dependent and the presence of endogenous acid is of pivotal importance for damage to occur [163, 164]. The extent and severity [164] as well as the probability [163] of damage are inversely correlated to intragastric pH. As a consequence, antisecretory drugs are widely used in the prevention and treatment of NSAID-associated gastric and duodenal ulcer [2••, 165••]. While H2-RAs, at standard doses, only protect the duodenum, PPIs prevent NSAID injury in both the duodenum and the stomach, where the majority of NSAID-related mucosal lesions occurs [166, 167].

Double-dose H2RAs and misoprostol (given four times daily) are effective at preventing chronic NSAID-related endoscopic gastric and duodenal ulcers [168], but compliance is poor. Mucosal protective compounds, such as rebamipide [169], seem also to be effective, but these drugs are not available outside Asia.

As shown in the ASTRONAUT trial [170], DR-PPIs are more effective for healing NSAID-associated duodenal than gastric ulcers. Indeed, after an 8-week treatment with omeprazole, only 81% of gastric ulcers were healed compared to 92% duodenal ulcers, a difference which was more marked at 4 weeks. Furthermore, in those patients requiring long-term treatment with NSAIDs, a loss of protection—even with continued treatment—became apparent [170,171,172].

In order to provide anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects throughout the 24 h, most NSAIDs are prescribed 2–3 times daily, or are given as “extended release” formulations. Moreover, some drugs (such as naproxen) are subject to enterohepatic circulation, which extends their injurious contact with the GI mucosa, especially at night. Consequently, patients taking NSAIDs and on a once-daily PPI will experience nocturnal acidification and hence be “unprotected” during the night (especially after midnight) and will continue to be at risk of mucosal injury or ulceration [162]. Thus, current preventive strategies with PPIs leave some unmet clinical needs [9]. The availability of a long-acting antisecretory drug, covering both the day- and nighttime, should provide improved mucosal protection from NSAID injury [10].

Vonoprazan efficacy in the treatment of NSAID gastropathy

Taking into account the healing efficacy of PPIs in patients with NSAID gastropathy, vonoprazan (20 mg daily, given for 6 weeks in DU and 8 weeks in GU) was evaluated in patients with NSAID ulcers or patients with H. pylori-positive, NSAID-associated ulcers [173]. The healing rates were 77.8% and 74.3%, respectively, a figure significantly lower than that achieved in H. pylori–associated ulcer (i.e., 93.5%). These results come from a multicenter, observational study in Akita Prefecture (Japan) [173] and need to be confirmed in a prospective, double-blind, controlled trial. In this study (in which patients with different ulcer pathogenesis were included), the overall healing rate was 85.1%, a value significantly lower than that observed in a phase 3 trial with vonoprazan for ulcer healing [174]. The rate difference between the two studies is likely due to differences in the proportion of NSAID-associated ulcers (i.e., 32% versus 15%), which proved more difficult to heal. Indeed, in the multivariate analysis, larger ulcers (OR: 3.8, 95 C.I. 1.3–11.5) and NSAID use (OR: 3.0, 95% C.I. 1.1–8.7) were associated with refractoriness [173]. No comparative study versus PPIs has yet been performed, but vonoprazan appeared to be effective in healing a large NSAID-associated, gastric ulcer refractory to 2-month treatment with double-dose PPIs, followed by additional 2 months with PPIs and misoprostol [175].

While PPIs reduce the development of peptic ulcer and related complications in patients taking NSAIDs, their beneficial effect is not expected to take place beyond the duodenum. Indeed, NSAID enteropathy is not a pH-dependent phenomenon and mucosal protection by PPIs is mainly, albeit not only, due to their antisecretory effect [164]. In healthy volunteers and patients, omeprazole did not prevent NSAID-associated intestinal damage, as evaluated by video capsule and/or fecal calprotectin measurement (for review, see [167]). Recent experimental and clinical evidence suggests that PPIs may actually aggravate NSAID injury in the small bowel [176]. Like rabeprazole, vonoprazan is associated with an increase of indomethacin-induced intestinal damage in mice [177]. Since, in this setting, rodent models proved to be predictive of human pharmacology [164], this vonoprazan-NSAID interaction should be taken into account, especially in patients under long-term anti-inflammatory and antisecretory therapy.

Vonoprazan efficacy in the secondary prevention of NSAID gastropathy

A phase 3, double-blind, multicenter, controlled trial in Japan [178] aimed to assess the non-inferiority of vonoprazan to a standard PPI, lansoprazole, for secondary prevention of NSAID-induced peptic ulcers during 24-week, and the safety of vonoprazan during an extended use ≥ 28 weeks. A similar study [179] reported the 24-week recurrence rate of aspirin-associated peptic ulcer in patients taking vonoprazan or lansoprazole. In both studies, patients were randomized (1:1:1) to receive either vonoprazan (20 or 10 mg daily) or lansoprazole (15 mg daily). These trials were preceded by a careful drug interaction study [180], showing the lack of PK interactions between vonoprazan and some NSAIDs (namely loxoprofen, diclofenac, and meloxicam) as well as between the P-CAB and aspirin. The same investigation also showed that aspirin-induced inhibition of platelet aggregation is not influenced by vonoprazan co-administration [180].

Results of the clinical studies (summarized in Table 6) allow to confirm the non-inferiority of both vonoprazan doses to lansoprazole 15 mg and to conclude that vonoprazan is effective in preventing ulcer recurrence in Japanese patients receiving NSAIDs or low-dose aspirin [178, 179].

Vonoprazan efficacy in the treatment of peptic ulcer

The efficacy and safety of vonoprazan in patients with gastric (GU) or duodenal (DU) ulcer was evaluated in two RCTs, using double-dummy blinding [174]. Four hundred fifty-six GU patients and 359 DU patients were randomized to receive vonoprazan (20 mg) or lansoprazole (30 mg) for 8 or 6 weeks, respectively. About 80% of the included patients were H. pylori–positive and some 10–15% were or had been on NSAID therapy. At the end of the treatment period, 93.5% of vonoprazan-treated patients and 93.8% of lansoprazole-treated patients had their GU healed. The corresponding figures for DU healing were 95.5%and 98.3%, for vonoprazan and lansoprazole, respectively. Statistical analysis showed that vonoprazan is non-inferior to lansoprazole with respect to GU healing and has similar efficacy for DU healing, while displaying an overlapping tolerability profile [174].

With the discovery of H. pylori infection, the causes, pathogenesis, and treatment of peptic ulcer disease have been rewritten [181]. Despite substantial advances, this disease remains an important clinical problem, largely because of the increasingly widespread use of NSAIDs for musculoskeletal disorders and low-dose aspirin for primary and secondary prophylaxis of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. Both H. pylori infection and NSAID use independently and, in combination, significantly increase the risk of peptic ulcer and ulcer bleeding [182]. However, albeit rare, a PU either H. pylori-negative and NSAID-negative also exists [181, 183], the management of which is still challenging [183]. In a multicenter, observational study in Japan [173], the healing rate of such idiopathic peptic ulcers with vonoprazan (20 mg daily) was 81.2%, a figure significantly lower than that achieved in H. pylori–associated ulcer (i.e., 93.5%), but similar to that of NSAID-associated ulcer. When patients with advanced gastric atrophy were excluded, the healing rate was even lower (i.e., 71.4%). At multivariate analysis, large ulcer size was associated with refractoriness [173].

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are resection techniques adopted for removal of early gastrointestinal malignancy [184]. EMR is indicated for upper GI lesions less than 20 mm provided they can be easily lifted and have a low risk of submucosal invasion. ESD should be considered for esophageal and gastric lesions that are bulky, show intramucosal carcinoma, or have a risk of superficial submucosal invasion [185, 186]. ESD is a more complex procedure accomplished in a stepwise manner using an assortment of tools and devices. Because of its ability to perform en bloc resection of larger lesions, ESD tends to cause larger artificial ulcers, resulting in a higher risk of complications. Perforation and delayed bleeding are the major complications of gastric ESD, with delayed bleeding and perforation being the most common [184].

Antisecretory drugs are usually prescribed after the procedure to promote the healing of the artificial ulcers caused by ESD and to reduce the risk of bleeding [187]. However, the optimal regimen for gastric acid suppression in this clinical setting remains to be established [188]. While H2RAs and PPIs are equally effective in healing iatrogenic ulcers and reducing epigastric pain, PPIs are more effective in preventing bleeding [187]. These drugs are therefore selected as the first-line treatment, but their efficacy is not complete due to the intrinsic limitations of this class of drugs [4, 5].

Due to the PK and PD superiority of P-CABs over PPIs, several studies with vonoprazan for healing of ESD-induced ulcers have been performed. An early meta-analysis [189] of the first 6 studies found that the likelihood that artificial ulcers are completely healed at 4–8 weeks after the procedure was significantly higher among patients receiving vonoprazan compared with those given PPIs. This superiority was confirmed by a subsequent meta-analysis [190]. However, two systematic reviews with meta-analysis [191, 192] and a network meta-analysis [193] did not find evidence of any superiority of vonoprazan over PPIs although one of these [191] highlighted a faster ulcer healing with the P-CAB. A more extensive review [194], including both RCTs and observational studies, pointed out that—while the overall ulcer healing rate did not differ between vonoprazan and PPIs—this new antisecretory compound was more effective when treating H. pylori–positive patients with ESD ulcers (Table 7). Almost all the studies evidenced a non-significant trend towards a reduced occurrence of delayed bleeding (see below).

Since the effect of PPIs appears not to be dose-dependent [195] and is enhanced by the combination with mucosal protective compounds (like, for instance, rebamipide) [193], mechanisms other than acid inhibition are likely involved in healing of those artificial ulcers. This can explain why more potent acid suppression with vonoprazan does not translate into an added benefit.

Upper GI bleeding: a forgotten or a too difficult indication for P-CABs?

There is an important role for therapeutic gastric acid suppression in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding either in the acute setting and for prevention of rebleeding [196,197,198,199]. For both these indications, PPIs have been more effective than H2RAs [165, 200]. The principles involved in raising intragastric pH to encourage clot formation and also reduce the failure of the clotting mechanisms are based on elegant in vitro work [201], done some 40 years ago but which remains highly relevant today as we now have antisecretory drugs, which are more potent than either the PPIs or the H2RAs. The evidence shows that coagulation is very sensitive to both acidity and proteolytic peptic activity. When pH drops to 6.8, coagulation mechanisms are less effective. Platelet aggregation is reduced by > 50% when the pH falls further to pH 6.4 and at pH < 5.9 platelets actually disaggregate. Furthermore, when the pH is increased to pH 6.8 or higher, platelet aggregation and platelet function are restored and the clotting time (as measured by the PT and PTT) returns to normal [201]. Subsequent studies have shown that—in patients with upper GI bleeding—fibrinolytic activity is enhanced and can be decreased by acid suppression [202], suggesting that this effect could be one of the mechanisms by which antisecretory drugs provide a benefit.

Also important to the formation and stability of any intragastric blood clot from a lesion in the stomach or duodenum is the proteolytic activity of gastric juice, predominantly, peptic activity. Indeed, increasing pH or heating gastric juice to denature pepsin markedly reduced clot lysis in vitro [203]. Thus, the stomach and proximal duodenum present a hostile environment during any episode of bleeding from a damaged or eroded vessel of a lesion in these upper GI sites. The acidity and proteolytic activity enable and accelerate continued bleeding and delay or prevent the formation or stability of any blood clot.

The current approach to medical treatment is predicated on our understanding of these intraluminal events which aims to achieve and maintain an intragastric pH above pH 6 to inhibit peptic activity [196••]. High-dose PPI treatment, when given intravenously, can achieve this target, although there is individual patient variability [204,205,206]. High-risk patients given PPIs should always be managed by the intravenous route and a significant reduction in further bleeding, the need for surgical intervention and mortality was confirmed by a meta-analysis of studies in patients after endoscopic treatment, who continued high-dose continuous infusion of PPIs in comparison to a control group on placebo infusion [207]. Guidelines recommend intravenous high-dose PPI before endoscopy with the aim to stabilize blood clot, to downgrade endoscopic stigmata of recent bleeding and also reduce the need for endoscopic therapy [196,197,198,199].

The new class of P-CAB drugs might fulfill the unmet needs in upper GI bleeding and improve outcomes with respect to rebleeding, transfusion requirements, surgical intervention, and mortality. However, the development of the P-CABs and their approval and introduction into clinical use has focused on the treatment of GERD and on the eradication of H. pylori infection. In spite of the noble objectives and obvious pathophysiological arguments, non-variceal upper GI bleeding has, to date, not been the focus of development for vonoprazan nor tegoprazan. Planning and undertaking studies in the management of acute upper GI bleeding present a considerable challenge but the superiority of oral vonoprazan on pH holding times when compared with esomeprazole and rabeprazole is clearly evident [29, 31, 208]. These three studies reported similar results comparing esomeprazole and/or rabeprazole with vonoprazan. Vonoprazan produced significantly higher median pH; pH holding time ratio (HTR) above pH 3, 4, and 5 and superior acid suppression over 0–24 h as well as 0–12 h and 12–24 h, with markedly higher nocturnal pH readings. None of the studies reported data for pH 6, although the 24-h intragastric pH curves from one [31] of the studies suggest that the results would, at least, be similar. In the SAMURAI pH study [208], the data reported for the pH 5 HTR for the cohort of healthy Japanese volunteers taking vonoprazan (20 mg once daily) versus rabeprazole (20 mg once daily) were (mean and SD) 80.9% (16.3) versus 38.1% (16.8), respectively. The treatment difference (LS mean and 95% CI) was 42.7% (28.3–57.2, p < 0.0001). In the second cohort, vonoprazan (20 mg once daily) was compared with double-dose rabeprazole (20 mg twice daily) and HTR results (Mean and SD) were 81.5% (16.8) versus 56.5% (16.7), respectively, with a treatment difference (LS mean and 95% CI) of 25.0% (13.3–36.7, p < 0.0011).

To date, there are no reports of the use of vonoprazan or tegoprazan in patients with upper GI bleeding, although several studies have addressed the use of vonoprazan in the management of ESD-related gastric ulcer following a variety of indications (see above). As previously discussed, the risk of rebleeding following ESD is a serious concern and reported to be about 5% [209,210,211,212] and usually occurs within the first 2 weeks post procedure [213, 214].

Acid suppression is a standard component of management to accelerate the healing of the ulcerated resection site and reduce the risk of rebleeding [187] [188]. Vonoprazan was therefore evaluated in this clinical setting. In one study [215], this P-CAB was given to 75 patients, prospectively enrolled prior to ESD, who were compared with 150 patients selected in a 2:1 ratio from a PPI-treated historical control cohort, matched for age, sex, ulcer size and H. pylori status. Despite that healing rate was higher in the PPI group, the incidence of post ESD bleeding in the vonoprazan group 1/75 (1.3%) was lower than in the PPI-treated patients (15/150–10%) (p < 0.01). Factors which affected post-ESD bleeding were the type of antisecretory drug (p = 0.016) and use of an antithrombotic agent (p = 0.014) [215]. The benefit in prevention of delayed bleeding was not confirmed by a subsequent study [216] and by several meta-analyses [190,191,192, 194] (Table 7).

The equivocal results with no difference between the P-CAB, vonoprazan, and PPIs in preventing rebleeding may result from the antisecretory effects of both drugs raising pH above the pH threshold to heal and prevent rebleeding, especially after the effective coagulation of larger vessels which occurs in properly performed ESD. The pH threshold for ulcer healing in the duodenum is well established at pH 3 [217] but for healing of gastric ulcer the situation is less clear and a careful analysis of 56 trials of antisecretory drugs in the treatment of benign gastric ulcer (GU), using an approach similar to that used for duodenal ulcer [217], showed that no such similar correlation existed unless placebo rates were included [218]. Correlation between GU healing was stronger with 24 h acid suppression than nocturnal acidity and duration of treatment was the most important variable. There was no obvious association between increasing degrees of acid suppression and improved ulcer healing rates when exploring omeprazole and various doses of H2RAs. Thus, the findings in these studies and the above meta-analyses are entirely consistent with the earlier conclusions on acid suppression and healing of gastric ulcer and do not argue for or against the proposal to evaluate the P-CABs in patients with upper GI bleeding. Given orally, these drugs have a potent and prolonged effect on the reduction of intragastric acidity and meet many of the criteria for still considering a development program for use in upper GI bleeding.

Safety of P-CABs

Although PPIs represent one of the safest drug classes available and have been used worldwide for almost 30 years, the number of publications concerning safety with DR-PPIs have increased dramatically with many widely publicized topics appearing in high-profile journals or the media. The methodological bias of these studies, including many confounding studies and often the lack of biological plausibility, have been extensively discussed in some thoughtful reviews [219••, 220•, 221]. Much of the evidence, which associates PPI treatment with serious long-term conditions, is weak with very low OR [222, 223]. In clinical practice, therefore, it is important to balance the undoubted benefits of treatment with PPIs with their purported risks and review the indications for the choice of drug and dose and to explain this carefully to the patient [2••, 14].

In light of the above concerns, the safety of the profound acid suppression obtained with P-CABs needs to be carefully investigated and patients treated with these new drugs should be followed up closely. Adverse events could be plausible and predictable (like, for instance, those concerning acid inhibition) while others (such as those molecule-dependent) are idiosyncratic and rare. While these latter will be unlikely with P-CABs (whose chemical structure is different from that of the current PPIs), those connected with the primary pharmacologic action (i.e., the antisecretory effect) may actually be exaggerated.

Clinical trials to date and subsequent meta-analyses [75,76,77, 142, 144, 145] have shown that the short-term safety of vonoprazan (the only widely used and thoroughly investigated P-CAB) in the short and medium term is excellent and comparable to that of PPIs. Since, in both healthy volunteers and patients with GERD, serum gastrin and pepsinogen I levels mirrored the antisecretory effect of vonoprazan [31, 224, 225], hypergastrinemia associated with long-term therapy [226] might be a concern. This issue was extensively addressed at the Hanbury Manor Workshop in 1995 [227] and there has been no convincing evidence of neoplastic change in subsequent years of follow-up [228]. In most studies of hypergastrinemia associated with the use of antisecretory drugs, gastrin levels do not continue to increase and promptly return to normal after discontinuation of therapy [229]. However, the results of a 52-week esophageal healing maintenance study in patients with reflux esophagitis [64], vonoprazan (10 or 20 mg once daily) induced a striking and progressive increase in serum gastrin (up to 678.0 pg/mL at 52 weeks with the 20-mg dose). There were no significant effects on gastric neuroendocrine cells at 24 and 52 weeks or changes in pepsinogen levels, but histology findings of the antral and corpus mucosa were not reported.

Due to the lack of long-term data, a 5-year safety study (the so called VISION study [226]) in 195 patients with healed erosive esophagitis taking vonoprazan (10 or 20 mg daily) or lansoprazole (15 or 30 mg daily) for maintenance was designed. The results of the 2-year interim analysis were presented at the Digestive Disease Week 2020. As expected from the stronger and longer-lasting antisecretory activity, mean serum gastrin pepsinogens, and chromogranin A were consistently higher in patients taking vonoprazan than in those given lansoprazole (Table 8). However, the mean pepsinogen I/pepsinogen II ratio was similar between the two groups and remained constant over time [226], which is reassuring [230,231,232]. Endoscopic findings showed a greater proportion of fundic gland polyps in the vonoprazan-treated patients at week 48, but the between-group difference was reduced at week 108, when the proportion of patients with hyperplastic polyps and with cobblestone mucosa was also greater than that seen in lansoprazole-treated patients (Table 9). In addition, patients on the P-CAB had more multiple white and flat elevated lesions compared to those on PPI [226]. Histologic examination showed that a greater proportion of patients in the vonoprazan group had hyperplasia of parietal cells, foveolar cells, and G cells than in the lansoprazole group. However, at week 108, no patient in either group showed malignant alterations of epithelial cells. In the vonoprazan group, 3 patients had hyperplastic endocrine cell micronest (ECM) at week 108 [226]. A recent report [233] found in 2 vonoprazan-treated patients with very high hypergastrinemia the appearance of several small white granular nodules in the gastric fundus (Fig. 2). Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging showed capillary dilation on their surface and histologic examination revealed a cystic dilated gland duct with stored secretions. These nodules decreased with drug tapering and disappeared after switching to an H2RA (i.e., famotidine, 40 mg daily) [233]. The authors suggested naming these nodules “white granules with slight elevation (WSGE),” similar to “white glove appearance (WGA),” sometimes observed in patients with autoimmune gastritis and hypergastrinemia [234] or under acid suppression therapy [235]. Despite being considered specific to P-CABs, these gastrin-related, reversible findings are likely the counterpart of the fundic gland polyps, which can be found in up to 23% of patients on long-term PPIs [236,237,238]. The mechanism by which antisecretory drugs may increase the prevalence of fundic gland polyps is uncertain. One plausible hypothesis is that fundic gland cysts are predisposed to by mucus-blocking of the fundic pits, as a result of the reduced flow of glandular secretions [239].

White glandular nodules, observed in a patient given vonoprazan (20 mg daily) for 11 weeks. a Endoscopic appearance; b histologic examination, showing a cystic dilated gland duct with stored secretions (from Kinoshita et al. [233])

As with PPI treatment, vonoprazan can reduce the gastric barrier to exogenous microorganisms, increasing the risk of enteric infections (e.g., traveler’s diarrhea) in those traveling to tropical regions [240, 241]. Dysbiosis [242] and changes in the gut microbiome [243, 244, 245••] have been reported during long-term PPI therapy and similar changes are now reported with vonoprazan. A preliminary publication [246] suggests that—with P-CABs—the effect may be more pronounced. The most markedly increased pathway in response to vonoprazan was LPS biosynthesis proteins and LPS biosynthesis. These changes are likely connected to the increase in intraluminal pH and are similar to those observed in the H. pylori microorganism in response to external pH changes [247]. Since LPS is a strong stimulant of immune response derived from gram-negative bacteria [287], these findings suggest that vonoprazan may stimulate the inflammatory status of the gut microbiome.

Conclusions and future perspectives

P-CABs clearly overcome many of the drawbacks and limitations of the DR-PPIs. In acid-related disorders, mucosal healing is directly related to the degree and duration of acid suppression and the length of treatment [10, 62, 93, 94]. Considering the difficulties encountered in attaining effective symptomatic control, particularly at night, using currently available DR-PPIs once daily, this new class of drugs achieves rapid, potent, and prolonged acid suppression and offers the chance of addressing many of the unmet clinical needs in GERD [4, 7, 8, 10], such as fast and assured healing of severe reflux esophagitis and achieving quick heartburn relief. The benefits of this prolonged acid suppression also extends to H. pylori eradication, where the control of intragastric pH, especially during the night, is crucial [13, 14] and where vonoprazan may provide an optimal dual therapy as a simple, reliable, and effective first-line treatment [13, 14]. Being a pH-dependent phenomenon [164], NSAID gastropathy is effectively prevented by vonoprazan, but its superiority over DR-PPIs has not been demonstrated in this clinical setting. However, based on the available evidence, erosive reflux disease, H. pylori infection, and secondary prevention of NSAID gastropathy can be considered established indications for vonoprazan (Table 10).

Other uses of this P-CAB are being evaluated, but clinical data are not yet sufficient to allow a definite answer on its efficacy and eventual superiority over our current standard of care (i.e., PPIs). The most important indication of upper GI (non-variceal) bleeding, where vonoprazan is likely to outweigh the benefits of DR-PPIs, has not yet explored (Table 10).

Hopefully, both vonoprazan (as well as tegoprazan and fexuprazan) will be fully evaluated also in Europe and North America, where the choice of antisecretory treatments remains limited. Only after worldwide extensive use can a critical evaluation of a new agent (in particular of a first-in-class drug) be made, allowing clinicians to determine whether it is effective and safe and whether it is really superior to currently available treatments. As with every new drug, overuse and misuse can occur and can be avoided only with responsible marketing and thoughtful prescribing, together with careful monitoring of patients treated. At the present time, the indications for treatment with vonoprazan or other P-CABs should be for the difficult-to-treat acid-related disorders and unmet needs, where the benefit to risk ratio is expected to be most favorable [13, 15].

Change history

11 March 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-021-00343-0

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Savarino V, Di Mario F, Scarpignato C. Proton pump inhibitors in GORD. An overview of their pharmacology, efficacy and safety. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59(3):135–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2008.09.016.

•• Scarpignato C, Gatta L, Zullo A, Blandizzi C. Effective and safe proton pump inhibitor therapy in acid-related diseases - a position paper addressing benefits and potential harms of acid suppression. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0718-z Comprehensive position paper discussing all the approved and off-label uses of PPIs.

Scarpignato C, Gatta L. Acid suppression for management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: benefits and risks. In: Morice A, Dettmar P, editors. Reflux aspiration and lung disease. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG; 2018. p. 269–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90525-9_23.

Hunt RH. Review article: the unmet needs in delayed-release proton-pump inhibitor therapy in 2005. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(Suppl 3):10–9.

Tytgat GN. Shortcomings of the first-generation proton pump inhibitors. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13(Suppl 1):S29–33.

•• Scarpignato C, Hunt RH. The potential role of potassium-competitive acid blockers in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2019;35(4):344–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/mog.0000000000000543 Detailed review describing the pharmacology of P-CABs and their efficacy in GERD.

Dickman R, Maradey-Romero C, Gingold-Belfer R, Fass R. Unmet needs in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;21(3):309–19. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm15105.

Katz PO, Scheiman JM, Barkun AN. Review article: acid-related disease-what are the unmet clinical needs? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(Suppl 2):9–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02944.x.

Scheiman JM. Unmet needs in non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced upper gastrointestinal diseases. Drugs. 2006;66(Suppl 1):15-21.

Scarpignato C, Pelosini I. Review article: the opportunities and benefits of extended acid suppression. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23(Suppl 2):23–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02945.x.

Scarpignato C, Hunt RH. Proton pump inhibitors: the beginning of the end or the end of the beginning? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8(6):677–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2008.09.004.

Scarpignato C, Pelosini I, Di Mario F. Acid suppression therapy: where do we go from here? Dig Dis. 2006;24(1–2):11–46. https://doi.org/10.1159/000091298.

Hunt RH, Scarpignato C. Potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs): are they finally ready for prime time in acid-related disease? Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6:e119. https://doi.org/10.1038/ctg.2015.39.

Hunt RH, Scarpignato C. Potent acid suppression with PPIs and P-CABs: what’s new? Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2018;16(4):570–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-018-0206-y.

Scarpignato C, Hunt RH. Editorial: towards extended acid suppression-the search continues. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(8):1027–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13384.

Inatomi N, Matsukawa J, Sakurai Y, Otake K. Potassium-competitive acid blockers: advanced therapeutic option for acid-related diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;168:12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.08.001.

Oshima T, Miwa H. Potent potassium-competitive acid blockers: a new era for the treatment of acid-related diseases. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24(3):334–44. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm18029.

Kim HK, Park SH, Cheung DY, Cho YS, Kim JI, Kim SS, et al. Clinical trial: inhibitory effect of revaprazan on gastric acid secretion in healthy male subjects. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(10):1618–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06408.x.

Garnock-Jones KP. Vonoprazan: first global approval. Drugs. 2015;75(4):439–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-015-0368-z.

Shin JM, Inatomi N, Munson K, Strugatsky D, Tokhtaeva E, Vagin O, et al. Characterization of a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker of the gastric h,k-atpase, 1-[5-(2-fluorophenyl)-1-(pyridin-3-ylsulfonyl)-1h-pyrrol-3-yl]-n-methyl methanamine monofumarate (tak-438). J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339(2):412–20. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.111.185314.

• Echizen H. The first-in-class potassium-competitive acid blocker, vonoprazan fumarate: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2016;55(4):409–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-015-0326-7 Detailed review on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the first P-CAB, vonoprazan.

Otake K, Sakurai Y, Nishida H, Fukui H, Tagawa Y, Yamasaki H, et al. Characteristics of the novel potassium-competitive acid blocker vonoprazan fumarate (TAK-438). Adv Ther. 2016;33(7):1140–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0345-2.

Martinucci I, Blandizzi C, Bodini G, Marabotto E, Savarino V, Marchi S, et al. Vonoprazan fumarate for the management of acid-related diseases. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18(11):1145–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2017.1346087.

Yang X, Li Y, Sun Y, Zhang M, Guo C, Mirza IA, et al. Vonoprazan: a novel and potent alternative in the treatment of acid-related diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(2):302–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-017-4866-6.

Sugano K. Vonoprazan fumarate, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, in the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: safety and clinical evidence to date. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756283x17745776. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756283x17745776.

• Graham DY, Dore MP. Update on the use of vonoprazan: a competitive acid blocker. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(3):462–6. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.018 Thoughtful remarks on current and potential clinical use of vonoprazan.

Sakurai Y, Nishimura A, Kennedy G, Hibberd M, Jenkins R, Okamoto H, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of single rising TAK-438 (vonoprazan) doses in healthy male japanese/non-japanese subjects. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6:e94. https://doi.org/10.1038/ctg.2015.18.

Jenkins H, Sakurai Y, Nishimura A, Okamoto H, Hibberd M, Jenkins R, et al. Randomised clinical trial: safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of repeated doses of TAK-438 (vonoprazan), a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, in healthy male subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(7):636–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13121.

Kagami T, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, Uotani T, Yamade M, Sugimoto M, et al. Potent acid inhibition by vonoprazan in comparison with esomeprazole, with reference to CYP2C19 genotype. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(10):1048–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13588.

Ohkuma K, Iida H, Inoh Y, Kanoshima K, Ohkubo H, Nonaka T, et al. Comparison of the early effects of vonoprazan, lansoprazole and famotidine on intragastric pH: a three-way crossover study. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2018;63(1):80–3. https://doi.org/10.3164/jcbn.17-128.

Sakurai Y, Mori Y, Okamoto H, Nishimura A, Komura E, Araki T, et al. Acid-inhibitory effects of vonoprazan 20 mg compared with esomeprazole 20 mg or rabeprazole 10 mg in healthy adult male subjects-a randomised open-label cross-over study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(6):719–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13325.