Abstract

Purpose of review

This review is aimed at summarizing the recently published ISCHEMIA trial (International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches) and how its findings may impact cardiac imaging for stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD) moving forward.

Recent findings

The ISCHEMIA trial compared an initial invasive management strategy with goal of complete coronary revascularization versus an initial medical therapy strategy among stable patients with newly diagnosed moderate to severe myocardial ischemia on non-invasive testing. The trial results showed that an early invasive strategy did not reduce the incidence of major cardiovascular events over 3.2 years of follow-up as compared to optimal medical therapy in patients with SIHD.

Summary

The results of the landmark ISCHEMIA trial solidified the importance of guideline-directed medical therapy and have provided more evidence against the prevailing dogma that moderate to severe ischemia on traditional stress testing mandates coronary revascularization. This trial was not designed to compare different cardiac imaging and stress testing modalities for the assessment of coronary artery disease in patients undergoing their index evaluation for SIHD; however, its design, which included coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) in most patients, and results have generated robust discussion regarding ways to improve non-invasive testing strategies in similar patient populations. We believe that increased utilization of CCTA to identify patients with and without high-risk SIHD, and advanced tests for ischemia, such as positron emission tomography and stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, when selected based on individual patient characteristics, may allow for improved decision-making and outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The evaluation and management of coronary artery disease (CAD) have been challenging physicians for centuries. The prevailing paradigm of managing stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD) has centered on medical therapy and coronary artery revascularization. For decades, physicians have turned to functional tests of ischemia to assess and risk stratify patients with SIHD. In the last 40 years, ischemic testing has also been utilized to identify patients who may benefit from revascularization in lieu of medical therapy alone [1]. However, the routine clinical practice of identifying ischemia and proceeding with revascularization in patients found to have angiographically obstructive CAD was never well proven in large-scale comparative effectiveness trials and has been repeatedly challenged [2,3,4]. Moreover, many have questioned if patients with moderate to severe ischemia on stress testing truly benefit from revascularization over medical therapy alone—as no previous studies had directly examined this clinical question in what was felt to be a high-risk population. The ISCHEMIA trial was designed to help answer the important clinical question—does revascularization in SIHD patients with moderate to severe ischemia outperform optimal medical therapy [5••]?

The ISCHEMIA trial

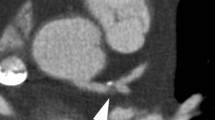

The ISCHEMIA trial randomized 5179 eligible patients (out of 8518 enrolled patients) with moderate to severe ischemia on stress testing (imaging or exercise stress electrocardiography [ExECG]) to either medical therapy or an invasive strategy that consisted of medical therapy plus plan for complete coronary revascularization [5••]. The study flow is summarized in Fig. 1 and inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1. All patients had no left main (LM) stenosis ≥ 50% but had at least at least one major coronary with greater than 50% stenosis. Ensuring obstructive CAD was achieved by having the majority (73%) of participants undergo coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA) [5••]. The remaining patients had renal dysfunction that precluded CCTA or their coronary anatomy was recently known. Importantly, prior to randomization, 21% of subjects referred based on moderate to severe ischemia on stress testing were found to have no significant CAD on CCTA. Additionally, ExECG without imaging was added to the study protocol in 2014 to improve the pace of enrollment and to make the study more generalizable given the extensive use of ExECG globally [5••]. Of the patients enrolled in the ISCHEMIA trial, 50% underwent perfusion imaging with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography myocardial perfusion imaging (PET MPI), 20% underwent stress echocardiography, 25% underwent ExECG, and 5% underwent stress cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) [5••]. Metrics for defining moderate to severe ischemia on the various stress testing modalities are summarized in Table 2. Ultimately, in those randomized to the invasive arm, 96% underwent invasive coronary angiography (ICA) with 79% undergoing revascularization (26% coronary artery bypass graft surgery), with decisions regarding optimal and ideally complete revascularization left to local treating physicians.

Participant flow diagram for the ISCHEMIA trial. Participant flow in the ISCHEMIA trial. CAD coronary artery disease, CMR cardiac magnetic resonance, CCTA coronary computed tomographic angiography, CV cardiovascular, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, MI myocardial infarction, MPI myocardial perfusion imaging, PET positron emission tomography, SCD sudden cardiac death, SIHD stable ischemic heart disease. *To ensure obstructive CAD was achieved, 73% of study participants underwent CCTA. The remaining patients had renal dysfunction that precluded CCTA or their coronary anatomy was recently known

At a median follow-up of 3.2 years, the estimated cumulative rates of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), cardiac hospitalization, and sudden cardiac death were 18.2% vs. 16.4% (p = 0.34) in the medical therapy vs invasive arms, respectively. The composite primary outcome (cardiovascular death, MI, hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest) occurred in 13.3% of the invasive therapy group compared to 15.5% of the optimal medical therapy group (hazard ratio [HR] 0.93, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.80–1.08, p = 0.34) [5••]. The major secondary end point (cardiovascular death or MI occurred in 11.7% vs 13.9% in the invasive and medial therapy groups, respectively (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.77–1.06, p = 0.21). Death from any cause occurred in 6.5% vs 6.4% in the invasive and medial therapy groups, respectively (p = 0.67). During the trial, invasive coronary angiography was performed in 28% of the optimal medical therapy group, with 23% of the medical therapy group ultimately undergoing a coronary revascularization procedure. Indications for catheterization in the optimal medical therapy group included suspected or confirmed events (13.8%), medical therapy failure (3.9%), and nonadherence (8.1%) [5••]. Subgroup analysis did not identify any clinical high-risk subgroup that benefited from an initial invasive strategy.

It is important to note that patients in the initial invasive arm achieved better angina relief at 1 year. Fifty percent of subjects in the invasive arm were angina free compared with 20% in the conservative arm. In terms of quality of life, patients with moderate or severe ischemia and frequent angina (daily, weekly, monthly) had better angina control with the invasive strategy [5••].

The major limitations of this trial were its relatively small sample size and slow enrollment, lower than anticipated adverse events rates in both groups, a 23% crossover rate of medical therapy to the revascularization, high utilization of (25%) of ExECG alone without imaging, low proportion of women (23%), and relatively short follow-up at 3.2 median years. The low event rate was likely related to the exclusion of most patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery, those with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 35%, and the potential selection bias due to low enthusiasm of providers to refer patients with known or suspected high-risk CAD to potential medical therapy alone. The final trial population had less than 20% with a prior MI and less than 5% of patients with a prior diagnosis of heart failure or a cerebrovascular event, respectively. Moreover, only 35% participants reported experiencing any angina in the 4 weeks prior to enrollment.

Despite these limitations, the results of this landmark clinical trial add significantly to a growing body of literature questioning the routine use of coronary revascularization to prevent hard cardiac events in patients with stable symptoms—even in those with moderate to severe ischemia—when aggressive medical therapy is also utilized. Others have questioned if traditional methods of ischemic testing are outdated and feel that newer imaging techniques (CMR MPI, PET MPI, and CCTA) should be utilized over ExECG, stress echocardiography, and SPECT MPI, the dominant forms of stress testing used in the ISCHEMIA trial. It is noteworthy that in the ISCHEMIA trial, CAD severity on anatomic testing (CCTA and ICA) was the most predictive variable for adverse events, irrespective of ischemia severity. Given these results and the high accuracy of CCTA to rule out left main CAD, many now argue that CCTA followed by medical therapy in those without severe angina or left main CAD should be the new testing paradigm in patients with stable symptoms.

Questions raised by the ISCHEMIA trial regarding non-invasive testing in patients with stable ischemic heart disease

The ISCHEMIA trial solidified the central role of medical therapy as the preferred initial treatment strategy in most patients with stable ischemic heart disease who meet ISCHEMIA trial inclusion criteria. The trial has also raised several important questions in the field of non-invasive imaging that have generated robust discussion. Indeed, the ISCHEMIA results challenge the current practice paradigm and clinical practice guidelines that have utilized ischemia testing to select patients with stable symptoms for invasive angiography. If moderate to severe abnormalities on stress testing do not identify a population most likely to benefit from an invasive approach, what testing strategy (if any) will? Naturally, given the utilization of CCTA in most ISCHEMIA trial participants to rule out left main CAD and to confirm the presence of angiographically significant CAD as well as the prognostic power of coronary atherosclerotic burden, some have suggested that CCTA should be the first test in similar patients, especially when there is no prior known CAD. Furthermore, the frequency of significant ischemia without significant CAD on CCTA (21%), in part related to false-positive stress testing, highlights the potential of coronary CTA to serve as a more efficient first-line test and potential gatekeeper to the catheterization lab in patients where this test is appropriate.

Evolving role of coronary CTA

As noted previously, the ISCHEMIA trial was the first large randomized controlled trial in the field of SIHD to include mainly patients with the moderate to severe ischemia on stress testing as well as anatomic evidence of obstructive CAD based on anatomic imaging, specifically utilizing CCTA. It is important to note that CCTA was not compared to functional testing. Previous trials such as PROMISE and SCOT-HEART demonstrated that CCTA is clinically useful as an alternative to or in addition to functional testing in low-risk patients [6, 7••]. While the PROMISE trial did not show a significant benefit at 2 years of CCTA versus conventional ischemia testing, those randomized to CCTA had a lower rate of MI at 1 year and lower rate of normal cardiac catheterization in those referred for ICA, highlighting the potential improvement in selection for ICA. The SCOT-HEART trial, however, demonstrated that CCTA, through its visualization of both obstructive and (especially) non-obstructive coronary atherosclerosis, was associated with more appropriate medical therapy for CAD and significantly lower rate of hard cardiovascular outcomes over 5 years of follow-up [7••].

In patients randomized following CCTA, most patients in ISCHEMIA had evidence of clinically relevant CAD, as reflected in the stenosis of at least 50% of multiple vessels in 79%, left anterior descending artery in 86.8%, and proximal left anterior descending artery un 46.8% [5••]. In a post hoc ISCHEMIA trial analysis, pre-randomization CCTA studies demonstrated a high degree of concordance with those who underwent subsequent ICA, 97.1% agreement for the absence of left main stenosis, and 92.2% agreement for stenosis in at least 1 non-left main coronary artery [8••].

Following the ISCHEMIA trial, many have begun to advocate that all patients without known CAD and angina should undergo CCTA to exclude LM disease while simultaneously starting medical therapy—even in the setting of moderate to severe ischemia on stress imaging. In this management algorithm, patients are only referred for revascularization if there is LM disease or similar high-risk obstructive CAD (multivessel CAD, etc.), unstable angina, or symptoms refractory to medical therapy. By virtue of this protocol, an anatomic study (CCTA or ICA) would be necessary for a patient undergoing evaluation for stable angina in order to exclude obstructive LM disease. This may lead more providers to obtain anatomic imaging initially at the expense of functional testing (bypassing stress imaging), in the evaluation of patients with SIHD and (in theory) lead to less downstream testing following CCTA. Naturally, CCTA would be the preferred non-invasive anatomic study option. If this route is taken, the provider should additionally ensure that the patient is similar to the population enrolled in ISCHEMIA, considering the other exclusion criteria such as LVEF < 35% (Table 1) as these patients may benefit from CMR MPI with delayed enhancement imaging to better define their cardiomyopathy. Proceeding with either an initial invasive strategy or conservative approach will then require an informed decision that will vary based on individual patient factors after risk/benefit discussion.

This algorithm though does not necessarily answer the question of what is causing symptoms in the absence of obstructive CAD and does not allow for the evaluation of coronary microvascular dysfunction but does avoid referrals to the catheterization lab based on false positive stress testing results. Newer techniques in CCTA have been developed to address these shortcomings to some degree. CT-based fractional flow reserve (FFRCT) allows for an estimation of invasively derived FFR. FFRCT can be performed without functional imaging and utilizes the same images from the original CCTA acquisition. In patients with extensive CAD, CCTA complemented by FFRCT has been shown to be non-inferior to ICA and invasive FFR for decision-making, and the identification of targets for revascularization. This data suggests FFRCT may be helpful when considering revascularization—particularly among patients with frequent symptoms [9, 10].

Given the false positive rate of functional stress testing and the clinical need to exclude LM stenosis, early evaluation with CCTA may be warranted or even preferred in many cases. The 2019 European Society of Cardiology guidelines on stable ischemic heart disease state that CCTA should be test of choice in most patients without previously known CAD when high diagnostic accuracy of CCTA can be expected [11••].

In light of the positive attributes of CCTA, this anatomic testing modality is not without limitations. These limitations can be patient specific, acquisition specific, or limited to general availability. Patient-specific contraindications such as renal impairment have been outlined in guidelines [12] which were also used in the ISCHEMIA trial. However, other patient conditions can limit the ability to obtain high diagnostic images including atrial fibrillation or frequent ectopy, morbid obesity, prior coronary stent placement, among others. Many of these limitations can be overcome with recent improvements in hardware, software, and acquisition techniques; however, these acquisitions generally require higher doses of radiation and should be performed and centers with expertise in performing high-quality CCTA. In light of these limitations, we believe ischemia testing will continue to play a role in patients who are not ideal candidates for CCTA. In general, the use of CCTA in patients with previously known CAD should be carefully considered [13]; as these patients have not been evaluated in the context of appropriate prospective clinical trials comparing outcomes to traditional ischemic testing.

The most controversial question on the imaging interpretation of this trial appears to be whether CCTA should be the forerunner in initial imaging for patients with SIHD. We believe this study may lead to increased use of CCTA as a first-line imaging study to evaluate SIHD patients with suspected obstructive CAD, ultimately to determine the role and intensity of medical therapy and to identify the overall burden of atherosclerosis for risk assessment instead of focusing on severity of stenosis alone. Furthermore, CCTA can be utilized to rule out high-risk anatomy given its unmatched negative predictive values compared to other imaging techniques [11••] and motivate providers to utilize more appropriate medical therapy for CAD if non-high-risk anatomy is discovered.

Novel approaches to assess myocardial ischemia

The ISCHEMIA trial outlines the weakness of non-invasive imaging assessments as tools to reliably diagnose obstructive CAD; a significant proportion (21% of the patients undergoing screening CCTA) of patients did not have 50% or greater stenosis, highlighting the differences between anatomic evidence of epicardial CAD, physiologic evidence of ischemia, and potential for imaging artifacts on stress imaging. In an ad hoc analysis of patients enrolled in the ISCHEMIA trial found that few (if any) clinical and stress testing parameters were predictive of LM disease on CCTA in patients with moderate or severe ischemia on stress testing [14].

These findings have led many to consider the role of evaluating myocardial ischemia with novel techniques that may have improved diagnostic and prognostic accuracy compared with the more traditional modalities (SPECT, stress echocardiography, ExECG) used in ISCHEMIA. Stress PET has extensive evidence of superior performance compared with traditional SPECT MPI in diagnosing and assessing risk in patients with CAD. PET MPI and increasingly CMR MPI with whole heart perfusion have powerful and well-vetted applications in evaluating microvascular ischemia, coronary flow reserve, and combination with calcium scoring from transmission scan [15].

Age and sex discrepancies did exist in the ISCHEMIA trial cohort as 22.6% of the study participants were women. Women were also noted to be more often excluded for having less ischemia on stress testing and less obstructive CAD on CCTA [16••]. While women are known to have higher rates of false positive stress test results, some have argued that the ischemia initially detected may have been secondary to microvascular ischemia. As such, PET MPI may be an ideal choice for anatomic (epicardial calcium detection) and functional evaluation to diagnose CAD (either epicardial or microvascular) as the cause of the patient’s symptoms in the absence of significant epicardial stenosis [17].

It is important to note that stress CMR is an excellent test for detecting ischemia compared to SPECT [18] and can also contribute to a better understanding of alternative causes of chest pain such as myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, or pericardial disease. Parametric mapping (T1 and T2) along with delayed enhancement imaging has proven to be very effective techniques in evaluating patients with chest pain syndromes and ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathies [19••, 20, 21]. There is emerging evidence in favor of the utilization of stress CMR; however, the ISCHEMIA trial included only 5% of the trial participants enrolled after stress CMR and the clinical utility remains to be explored and validated [5••, 22]. The MR-INFORM trial compared a stress CMR management strategy with FFR-guided management of patients with typical angina and showed that a CMR strategy safely guided patient management and reduced the number of invasive coronary angiograms and revascularization [23••]. Guideline-supported indications of CMR continue to grow as we see that CMR is an excellent non-invasive imaging modality to evaluate new cardiomyopathies including infiltrative disease with amyloid, sarcoid, HCM, and microvascular angina and viability [13, 24]. Even though the vast majority of PET/CMR MPI is pharmacological and not physiological, CMR provides additional vascular function at the epicardial and microvascular levels and allows for continued medical therapy when vasospastic angina or microvascular angina is considered [18, 25].

Unfortunately, CMR and PET MPI were underrepresented in the ISCHEMIA trial. It remains to be seen if these techniques, with higher accuracy and the ability to better define viability, prior infarction more accurately, might outperform traditional techniques to evaluate SIHD in a similar trial design. Unfortunately, the chief limitation in use of these novel modalities remains access and cost. Of important note, the recent SCMR registry study SPINS demonstrated the diagnostic and cost-effective value of CMR in the USA, but this has yet to be incorporated in guidelines or reimbursement coverage policies [26]. Regardless, we are confident that these novel imaging technique modalities provide clinicians the ability to perform patient-centered imaging with an individualized approach to best answer the clinical questions at hand.

Confidence with medical therapy moving forward

The largest impact of the ISCHEMIA trial on medicine will not be on cardiac imaging, but rather medical therapy for CAD. The ISCHEMIA trial results continue to support growing evidence that fist-line medical therapy in patients with SIHD is not inferior to revascularization [2,3,4]. Importantly, this benefit occurs in the background of widespread availability/accessibility, high procedural success, and low complication rates of coronary revascularization techniques. The ISCHEMIA trial provides more evidence allowing clinicians to pursue an initial strategy of medical therapy—even among patients who have moderate to severe ischemia—and this alone may be highly impactful and important for the millions of patients who have CAD.

In the context of the ISCHEMIA trial, we believe identifying patients who have undiagnosed CAD by CCTA will play an important role going forward. The ability of CCTA to identify patients with non-obstructive CAD who might benefit from more aggressive primary prevention makes this an attractive first-line test in patients without known CAD. In addition to blood pressure control and lifestyle changes, the field of lipid-preventive pharmacotherapy now includes cholesterol-lowering agents such as statins, ezetimibe, and PCSK9-inhibitors, as well as the newer agents of high-dose omega-3, fibrates, aspirin, and cardiorenoprotective hypoglycemic agents [27, 28]. The updated 2019 ESC guidelines highlight the aims of pharmacological management of CAD to reduce angina symptoms and exercise-induced ischemia, and prevent cardiovascular events [11••]. The general strategy includes no universal definition of an optimal treatment in patients with CAD and utilization of the above drugs adapted to each patient’s characteristics and preference with a goal to eliminate angina and lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by at least 50% from baseline and to < 55 mg/dL [11••].

Another question that has be raised following the ISCHEMIA trial is whether clinicians should evaluate for ischemia if medical therapy will be used to treat the majority of stable patients who do not have high-risk CAD. This trial does not provide concrete indications to avoid ischemia testing given there is a significant body of evidence demonstrating that progressive ischemia is associated with increased risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (across all ischemia imaging modalities) [23, 29••]. Ischemic evaluation will continue to have an important clinical role in many patients. This is due in part to the ISCHEMIA trial not including very low or high-risk populations; approximately 54% of the patients in the trial had severe ischemia. We do not know how severe the ischemia was, and it is likely that due to selection bias, individuals who had extensive ischemia, reduced ejection fraction, or other high-risk features were less likely to be randomized in the study.

The results of the ISCHEMIA trial are consistent with those of previous trials demonstrating revascularization had no survival benefit in patients with SIHD without obstructive LM disease. This trial does not change the indication for revascularization in SIHD that has already been established. SIHD continues to warrant a patient-centered approach—one size does not fit all. Management should take into consideration the clinical history, impact on quality of life, risk factors, and the burden of ischemia and atherosclerosis, if known. A multidisciplinary approach and an up-front frank discussion is necessary regarding an invasive approach; specifically, addressing risks and benefits and the fact that revascularization may not reduce likelihood of cardiovascular death or MI.

Conclusions

The landmark results of the ISCHEMIA trial have provided more evidence against the prevailing dogma that moderate to severe ischemia warrants routine coronary revascularization. Additionally, it provides strong evidence that medical therapy is an effective treatment for CAD when compared to patients undergoing revascularization for moderate to severe ischemia on stress testing. This trial, like so many before its publication, demonstrates that appropriate medical therapy for patients with CAD continues to be absolutely paramount. This trial was not designed to compare different cardiac imaging and stress testing modalities for the assessment of CAD in patients undergoing their index evaluation for SIHD; however, its results have generated a myriad of predictions and opinions towards the future cardiac imaging in this population. We believe this trial demonstrates that CCTA can be used to effectively diagnose CAD with high sensitivity and allow for identification of high-risk anatomy that warrants revascularization, if appropriate. The results of the ISCHEMIA trial add to a growing belief that a paradigm shift should occur in the evaluation of SIHD. In evaluating most patients with SIHD, we should first ask ourselves “is coronary atherosclerosis present” and not “is ischemia present”? CCTA allows clinicians to diagnose atherosclerosis and plaque characteristics allowing for tailored medical therapies versus simply identifying ischemia. In this context, we believe the use of CCTA as part of the initial evaluation for CAD will only continue to grow. However, diagnosing myocardial ischemia will remain critically important for many patients, particularly those with established CAD, as we know that progressive ischemia portends worse outcomes. Additionally, many high-risk patients that were excluded by the ISCHEMIA trial remain ideal candidates for ischemia testing. We believe this trial highlights the importance of considering the use of novel approaches to assess myocardial ischemia using PET and CMR MPI as they have been shown to be superior in diagnosing obstructive CAD compared to traditional imaging techniques and also allow for identification of microvascular disease among other cardiac pathologies. The results of this trial will undoubtedly impact the clinical/imaging assessment and treatment of patients with SIHD in the years to come.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, et al. Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003;107:2900–7. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000072790.23090.41.

Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa070829.

Al-Lamee R, Thompson D, Dehbi H-M, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32714-9.

BARI 2D Study Group, Frye RL, August P, et al. A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2503–15. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0805796.

•• Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1395–407. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1915922The ISCHEMIA trial publication.

Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, et al. Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1291–300. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1415516.

•• SCOT-HEART Investigators, Newby DE, Adamson PD, et al. Coronary CT angiography and 5-year risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:924–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1805971 The SCOT-HEART trial showed that CCTA is a reasonable alternative to standard of care for evaluation of SIHD patients who are low to intermediate risk. Interestingly, this trial showed that patients assigned to the CCTA were on more appropriate medical therapy for CAD.

Mancini GBJ, Leipsic J, Budoff MJ, et al. Coronary CT angiography followed by invasive angiography in patients with moderate or severe ischemia-insights from the ISCHEMIA Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.11.012 Recent post hoc analysis of the ISCHEMIA which demonstrated a high degree of concordance of the CCTA studies with those who ultimately underwent ICA.

Collet C, Onuma Y, Andreini D, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography for heart team decision-making in multivessel coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3689–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy581.

Celeng C, Leiner T, Maurovich-Horvat P, et al. Anatomical and functional computed tomography for diagnosing hemodynamically significant coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:1316–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.07.022.

•• Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: the Task Force for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:407–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425 Most updated ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes.

Narula J, Chandrashekhar Y, Ahmadi A, et al. SCCT 2021 Expert consensus document on coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcct.2020.11.001.

Hanson CA, Bourque JM. Functional and anatomical imaging in patients with ischemic symptoms and known coronary artery disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21:79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-019-1155-3.

Senior R, Reynolds H, Min J, et al. Prediction of left main disease using clinical and stress test parameters. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(20)30679-3.

Dewey M, Siebes M, Kachelrieß M, et al. Clinical quantitative cardiac imaging for the assessment of myocardial ischaemia. Nat Rev. Cardiol. 2020;17:427–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-0341-8.

•• Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Bangalore S, et al. Baseline characteristics and risk profiles of participants in the ISCHEMIA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:273–86. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0014 Methodology paper for the ISCHEMIA trial.

Pelletier-Galarneau M, Dilsizian V. Microvascular angina diagnosed by absolute PET myocardial blood flow quantification. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22:9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-020-1261-2.

Greenwood JP, Motwani M, Maredia N, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular magnetic resonance and single-photon emission computed tomography in women with suspected coronary artery disease from the Clinical Evaluation of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Coronary Heart Disease (CE-MARC) Trial. Circulation. 2014;129:1129–38. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000071.

•• Robinson AA, Chow K, Salerno M. Myocardial T1 and ECV measurement: underlying concepts and technical considerations. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:2332–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.06.031 Comprehensive review on T1 mapping and ECV by CMR.

Hanson CA, Kamath A, Gottbrecht M, et al. T2 relaxation times at cardiac mri in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2020;200:989. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020200989.

Sujith K, Nebiyu A, Katwal Arabindra B, et al. Late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance predicts adverse cardiovascular outcomes in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:250–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.001144.

Knott KD, Andreas S, Augusto JB, et al. The prognostic significance of quantitative myocardial perfusion. Circulation. 2020;141:1282–91. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044666.

Nagel E, Greenwood JP, McCann GP, et al. Magnetic resonance perfusion or fractional flow reserve in coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1716734 Important study comparing an FFR-based management with stress CMR. Ultimately, stress CMR was associated with a lower incidence of coronary revascularization than FFR and wasnoninferior to FFR with respect to major adverse cardiac events.

Bax JJ, Delgado V. Detection of viable myocardium and scar tissue. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:1062–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jev200.

Kotecha T, Martinez-Naharro A, Boldrini M, et al. Automated pixel-wise quantitative myocardial perfusion mapping by CMR to detect obstructive coronary artery disease and coronary microvascular dysfunction: validation against invasive coronary physiology. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:1958–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.12.022.

Ge Y, Pandya A, Steel K, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging for stable chest pain syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:1505–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.02.029.

Mortensen MB, Steffensen FH, Bøtker HE, et al. CAD severity on cardiac CTA identifies patients with most benefit of treating LDL-cholesterol to ACC/AHA and ESC/EAS targets. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:1961–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.03.017.

Cainzos-Achirica M, Miedema MD, McEvoy John W, et al. Coronary artery calcium for personalized allocation of aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in 2019. Circulation. 2020;141:1541–53. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.045010.

•• Shaw L, Kwong RY, Nagel E, et al. Cardiac imaging in the post-ISCHEMIA Trial era: a multisociety viewpoint. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:1815–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.05.001 Recent publication written by members of each of the individual modality-specific societies in response to the results of the ISCHEMIA trial.

Relationships with industry

None.

Funding

Dr. Hanson and Dr. Patel are supported by National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (grant no. 5T32EB003841).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human and animal rights and informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

Christopher A. Hanson, Toral R. Patel, and Todd C. Villines declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Imaging

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanson, C.A., Patel, T.R. & Villines, T.C. The New Role of Cardiac Imaging Following the ISCHEMIA Trial. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 23, 36 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-021-00911-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-021-00911-8