Abstract

Purpose of review

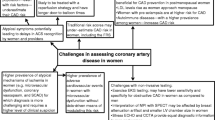

Increased recognition of risk factors and improved knowledge of sex-specific presentations has led to improved clinical outcomes for women with cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared to two decades ago. Yet, CVD remains the leading cause of death for women in the USA. Women have unique risk factors for CVD that continue to go under-recognized by their physicians.

Recent findings

In a nationwide survey of primary care physicians (PCPs) and cardiologists, only 22% of PCPs and 42% of cardiologists reported being extremely well prepared to assess CVD risk in women. A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologist (ACOG) recommends that cardiologists and obstetricians and gynecologists (Ob/Gyns) collaborate to promote CVD risk identification and reduction throughout a woman’s lifetime.

Summary

We suggest a comprehensive approach to identify unique and traditional risk factors for CVD in women, address the gap in physician knowledge, and improve cardiovascular care for women.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(12):e67–e492.

Aggarwal NR, Patel HN, Mehta LS, Sanghani RM, Lundberg GP, Lewis SJ, et al. Sex differences in ischemic heart disease: advances, obstacles, and next steps. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(2):e004437.

• Gu Q, Burt VL, Paulose-Ram R, Dillon CF. Gender differences in hypertension treatment, drug utilization patterns, and blood pressure control among US adults with hypertension: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2004. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21(7):789–98. Gu et al. shows that women with hypertension, despite being on similar treatment regimens as men achieve blood pressure control at a significantly lower rate compared with men, while compliance and treatment rates are higher in women.

• Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937–52. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study) was a large, international, case-control study designed to determine the importance of risk and protective factors for CHD worldwide. Study showed that hypertension and diabetes had higher population attributable risk in women compared to men.

Peters SA, Huxley RR, Woodward M. Diabetes as risk factor for incident coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts including 858,507 individuals and 28,203 coronary events. Diabetologia. 2014;57(8):1542–51.

Huxley RR, Peters SA, Mishra GD, Woodward M. Risk of all-cause mortality and vascular events in women versus men with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(3):198–206.

Njolstad I, Arnesen E, Lund-Larsen PG. Smoking, serum lipids, blood pressure, and sex differences in myocardial infarction. A 12-year follow-up of the Finnmark Study. Circulation. 1996;93(3):450–6.

Wenger NK. Women and coronary heart disease: a century after Herrick: understudied, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. Circulation. 2012;126(5):604–11.

Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, Grines CL, Krumholz HM, Johnson MN, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in women: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(9):916–47.

Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Hayes SN, Walsh BW, et al. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation. 2005;111(4):499–510.

Bairey Merz CN, Andersen HS, Shufelt CL. Gender, cardiovascular disease, and the sexism of obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(18):1958–60.

• Leifheit-Limson EC, D'Onofrio G, Daneshvar M, Geda M, Bueno H, Spertus JA, et al. Sex differences in cardiac risk factors, perceived risk, and health care provider discussion of risk and risk modification among young patients with acute myocardial infarction: the VIRGO Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(18):1949–57. The VIRGO (Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients) showed that among adults aged 18 to 55 hospitalized for an acute myocardial infarction there was sex disparity in prior discussion with healthcare providers about modification of cardiovascular risk factors despite similar risk profile, specifically women were 20% less likely to report such discussions.

Dhawan S, Bakir M, Jones E, Kilpatrick S, Merz CN. Sex and gender medicine in physician clinical training: results of a large, single-center survey. Biol Sex Differ. 2016;7(Suppl 1):37.

Lewis BG, Halm EA, Marcus SM, Korenstein D, Federman AD. Preventive services use among women seen by gynecologists, general medical physicians, or both. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):945–52.

Morgan MA, Lawrence H 3rd, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists’ approach to well-woman care. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):715–22.

Shaw LJ, Pepine CJ, Xie J, Mehta PK, Morris AA, Dickert NW, et al. Quality and equitable health care gaps for women: attributions to sex differences in cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(3):373–88.

• Brown HL, Warner JJ, Gianos E, Gulati M, Hill AJ, Hollier LM, et al. Promoting risk identification and reduction of cardiovascular disease in women through collaboration with obstetricians and gynecologists: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Circulation. 2018. This advisory paper calls for counceling for healthy lifestlye and behavious in the care of all women as well as using well-women exam as an opportunity for early detection and modification of CVD risk factors. The paper discusses importance of bridging the gap between ob-gyn and cardiology which are important pillars of Women's health. Authors also address need for creation and use of templetes for comprehensive CV risk assessment in women. Implementation of consumer devices, apps, and social media networks to educate and empower women was also encouraged by the authors.

Pasternak RC, Abrams J, Greenland P, Smaha LA, Wilson PW, Houston-Miller N. 34th Bethesda Conference: task force #1—identification of coronary heart disease risk: is there a detection gap? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(11):1863–74.

Jewelewicz R, Schwartz M. Premature ovarian failure. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1986;62(3):219–36.

Gaudineau A, Ehlinger V, Vayssiere C, Jouret B, Arnaud C, Godeau E. Factors associated with early menarche: results from the French Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:175.

• Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;2019. 2019 ACC/AHA primary CVD prevention guidelines provide alorithms for CVD risk stratification and relay recommendations on clinical management of patients in different risk categories. Guidline emphasizes importance of clinician patient shared decision making while establishing treatment plan. In addition, incorporation of the risk enhancing factors, which include female specific and female predominant risk factors in risk assessment is recommended in intermediate risk patients. Use of coronary artery calcium scoring to refine risk category is also recommended in patients with intermediate cardiovascular risk if decision regarding treatment is not established.

• Spector TD. Rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 1990;16(3):513–37. In 1990 Dr. Spector reported that rheumatoid arthritis is two to tree times more common in women. It is assumed that the risk for the higher incidence may be related to sex hormones. Pregnancy and oral contraceptive pills may be protective or may delay and modify course of the disease.

Mason JC, Libby P. Cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic inflammation: mechanisms underlying premature cardiovascular events in rheumatologic conditions. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(8):482-9c.

Stamatelopoulos KS, Kitas GD, Papamichael CM, Chryssohoou E, Kyrkou K, Georgiopoulos G, et al. Atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis versus diabetes: a comparative study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(10):1702–8.

Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, Conte CG, Medsger TA Jr, Jansen-McWilliams L, et al. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145(5):408–15.

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol. Circulation. 2018;2018:CIR0000000000000625.

• Saha KR, Rahman MM, Paul AR, Das S, Haque S, Jafrin W, et al. Changes in lipid profile of postmenopausal women. Mymensingh Med J. 2013;22(4):706–11. Saha et al. showed that postmenopausal women have a more atherogenic lipid profile compared to reproductive age group. Authors reported statistically significant increase in total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol and reduction in HDL cholesterol in menopausal women compared to pre-menopausal women.

Shaw LJ, Bairey Merz CN, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kelsey SF, et al. Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: part I: gender differences in traditional and novel risk factors, symptom evaluation, and gender-optimized diagnostic strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(3 Suppl):S4–S20.

Wellons M, Ouyang P, Schreiner PJ, Herrington DM, Vaidya D. Early menopause predicts future coronary heart disease and stroke: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Menopause. 2012;19(10):1081–7.

Anderson SA, Barry JA, Hardiman PJ. Risk of coronary heart disease and risk of stroke in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176(2):486–7.

Conway GS, Agrawal R, Betteridge DJ, Jacobs HS. Risk factors for coronary artery disease in lean and obese women with the polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 1992;37(2):119–25.

Kaaja RJ, Greer IA. Manifestations of chronic disease during pregnancy. JAMA. 2005;294(21):2751–7.

Banerjee M, Cruickshank JK. Pregnancy as the prodrome to vascular dysfunction and cardiovascular risk. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006;3(11):596–603.

Wenger NK. Recognizing pregnancy-associated cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(2):406–9.

Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335(7627):974.

Vaught AJ, Kovell LC, Szymanski LM, Mayer SA, Seifert SM, Vaidya D, et al. Acute cardiac effects of severe pre-eclampsia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(1):1–11.

Heida KY, Velthuis BK, Oudijk MA, Reitsma JB, Bots ML, Franx A, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with a history of spontaneous preterm delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(3):253–63.

Emerging Risk Factors C, Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Perry PL, Di Angelantonio E, Thompson A, et al. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA. 2009;302(4):412–23.

Shlipak MG, Simon JA, Vittinghoff E, Lin F, Barrett-Connor E, Knopp RH, et al. Estrogen and progestin, lipoprotein(a), and the risk of recurrent coronary heart disease events after menopause. JAMA. 2000;283(14):1845–52.

Davidson MH, Ballantyne CM, Jacobson TA, Bittner VA, Braun LT, Brown AS, et al. Clinical utility of inflammatory markers and advanced lipoprotein testing: advice from an expert panel of lipid specialists. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5(5):338–67.

Langsted A, Nordestgaard BG. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting lipoprotein(a). Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2019;21(8):30.

Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, Bang H, Coresh J, Folsom AR, Heiss G, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and risk for incident coronary heart disease in middle-aged men and women in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2004;109(7):837–42.

Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM Jr, Kastelein JJ, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2195–207.

Lakoski SG, Cushman M, Criqui M, Rundek T, Blumenthal RS, D'Agostino RB Jr, et al. Gender and C-reactive protein: data from the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) cohort. Am Heart J. 2006;152(3):593–8.

Khera A, McGuire DK, Murphy SA, Stanek HG, Das SR, Vongpatanasin W, et al. Race and gender differences in C-reactive protein levels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(3):464–9.

Tracy RP, Lemaitre RN, Psaty BM, Ives DG, Evans RW, Cushman M, et al. Relationship of C-reactive protein to risk of cardiovascular disease in the elderly. Results from the Cardiovascular Health Study and the Rural Health Promotion Project. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17(6):1121–7.

Visser M, Bouter LM, McQuillan GM, Wener MH, Harris TB. Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. JAMA. 1999;282(22):2131–5.

Larsson A, Hansson LO, Akerfeldt T. Weight reduction is associated with decreased CRP levels. Clin Lab. 2013;59(9–10):1135–8.

Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, Sheedy PF, Schwartz RS. Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation. 1995;92(8):2157–62.

Lamina C, Meisinger C, Heid IM, Lowel H, Rantner B, Koenig W, et al. Association of ankle-brachial index and plaques in the carotid and femoral arteries with cardiovascular events and total mortality in a population-based study with 13 years of follow-up. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(21):2580–7.

Hecht H, Blaha MJ, Berman DS, Nasir K, Budoff M, Leipsic J, et al. Clinical indications for coronary artery calcium scoring in asymptomatic patients: expert consensus statement from the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2017;11(2):157–68.

Lakoski SG, Greenland P, Wong ND, Schreiner PJ, Herrington DM, Kronmal RA, et al. Coronary artery calcium scores and risk for cardiovascular events in women classified as “low risk” based on Framingham Risk Score: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2437–42.

Kavousi M, Desai CS, Ayers C, Blumenthal RS, Budoff MJ, Mahabadi AA, et al. Prevalence and prognostic implications of coronary artery calcification in low-risk women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2126–34.

Shaw LJ, Min JK, Nasir K, Xie JX, Berman DS, Miedema MD, et al. Sex differences in calcified plaque and long-term cardiovascular mortality: observations from the CAC Consortium. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(41):3727–35.

Lange S, Trampisch HJ, Haberl R, Darius H, Pittrow D, Schuster A, et al. Excess 1-year cardiovascular risk in elderly primary care patients with a low ankle-brachial index (ABI) and high homocysteine level. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178(2):351–7.

Pimple P, Hammadah M, Wilmot K, Ramadan R, Al Mheid I, Levantsevych O, et al. Chest pain and mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia: sex differences. Am J Med. 2018;131(5):540–7 e1.

Nicholson A, Kuper H, Hemingway H. Depression as an aetiologic and prognostic factor in coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of 6362 events among 146 538 participants in 54 observational studies. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(23):2763–74.

Rozanski A, Gransar H, Kubzansky LD, Wong N, Shaw L, Miranda-Peats R, et al. Do psychological risk factors predict the presence of coronary atherosclerosis? Psychosom Med. 2011;73(1):7–15.

Barth J, Schumacher M, Herrmann-Lingen C. Depression as a risk factor for mortality in patients with coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(6):802–13.

Schultz WM, Kelli HM, Lisko JC, Varghese T, Shen J, Sandesara P, et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular outcomes: challenges and interventions. Circulation. 2018;137(20):2166–78.

Funding

This work was supported by Emory Women’s Heart Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Nino Isakadze, Karen Law, Mary Dolan, and Gina P. Lundberg each declare no potential conflicts of interest. Puja K. Mehta reports research support from Sanofi Aventis.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Women’s Health

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Isakadze, N., Mehta, P.K., Law, K. et al. Addressing the Gap in Physician Preparedness To Assess Cardiovascular Risk in Women: a Comprehensive Approach to Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Women. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 21, 47 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-019-0753-0

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-019-0753-0