Abstract

Purpose of Review

We summarized peer-reviewed literature on aggressive episodes perpetrated by adult patients admitted to general hospital units, especially psychiatry or emergency services. We examined the main factors associated with aggressive behaviors in the hospital setting, with a special focus on the European experience.

Recent Findings

A number of variables, including individual, historical, and contextual variables, are significant risk factors for aggression among hospitalized people. Drug abuse can be considered a trans-dimensional variable which deserves particular attention.

Summary

Although mental health disorders represent a significant component in the risk of aggression, there are many factors including drug abuse, past history of physically aggressive behavior, childhood abuse, social and cultural patterns, relational factors, and contextual variables that can increase the risk of overt aggressive behavior in the general hospital. This review highlights the need to undertake initiatives aimed to enhance understanding, prevention, and management of violence in general hospital settings across Europe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While the trend of 1980s medical literature was to indicate the substantial lack of an increased risk for aggression in patients with psychiatric disorders [1], in the following decades, changes in mental health services including the development of consultation-liaison psychiatric units [2] have determined a different approach to this problem, and by the 1990s, the association between mental illness and aggression seemed to be confirmed [3,4,5].

Currently, findings suggest that up to 50% of patients with psychiatric disorders show aggressive symptoms, as compared to less than 2% of the general population [6•]. Likewise, recent studies hint at an increased risk of aggression among patients affected by mental disorders admitted to the hospital [7••, 8].

In Europe, significant levels of violence from patients in healthcare settings have been identified, with variance of reporting between countries, the highest rates being for France, UK, and Germany and the lowest rates for Norway and the Netherlands [9].

However, violence in healthcare settings is on the rise [10], to the point that the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work has defined the healthcare sector as one with the highest rates of violence [11]. The magnitude of the problems is such that a group of experts founded the “European Violence in Psychiatry Research group” (www.eviprg.eu) aimed to enhance the understanding, prevention, and management of violence in medical settings.

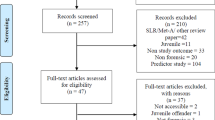

The aim of the present narrative review is to summarize recent peer-reviewed literature from European countries on aggressive episodes in adult patients with mental illnesses admitted to psychiatric units or general hospitals.

For this purpose, we will use the terms “aggression” and “violence” as synonyms and in accordance with the following definition: “physical, psychological, sexual, or other forms of actions which risk causing harm or paining the person exposed” [12].

Aggression in Psychiatric Settings

Research into aggression in psychiatric services is fraught with difficulties. Many differences in methodology, in the definition of what is to be considered an aggressive behavior, as well as in the organization of psychiatry settings, determine a great variation in reported rates of aggression and make it difficult to compare and generalize findings [13].

The dimension of the phenomenon appears however critical if a recent meta-analysis highlighted that psychiatric nurses have about three times the odds of physical assault from patients than nurses in nonpsychiatric settings [14].

According to a review [15••], in acute psychiatric units, between 24 and 80% of mental health workers experienced at least one aggression during their career: verbal assaults affected 46–78.6% of staff, threats 43–78.6%, and sexual harassment 9.5–37.2%.

Another meta-analysis [16] of studies carried out on acute psychiatric wards in high-income countries showed that the pooled proportion of patients who committed at least one act of physical aggression was as high as 17%.

The documented rates of different kinds of reported aggression vary between continents, for example, it was suggested that sexual harassment rates seem lower in European studies [17], while reports of physical assault are more frequent in Anglo regions and bullying more common in the Middle East [18••].

As far as Europe is concerned, an interesting cross-sectional, comparative study between UK and Sweden using the Arnetz Questionnaire [19] found that, in psychiatric inpatient settings, more British than Swedish professionals were at risk of any kind (the study did not differentiate between verbal and physical aggression) of aggression by patients [20]. A more recent retrospective study, using the Patient Conflict Checklist [21] to analyze aggressive enactments in 522 patients of 84 acute psychiatric wards during the first 2 weeks of admission, showed that 51% of patients displayed verbal aggression in at least one occasion, 25% enacted aggression toward objects, and 20% was aggressive toward others. These findings suggest that in UK, aggression episodes might occur (or are reported) more frequently than in other European countries [22]. In general, however, in European hospital psychiatric settings, preoccupying rates of both verbal and physical violence are enacted by patients, and this condition has remained unvaried over the last two decades, according to recent studies based on specifically developed questionnaires and interviews carried out in Norway [23], England [24], and Italy [25].

A UK-based investigation among 194 subjects with a first episode psychosis using the Psychiatric and Personal History Schedule (PPHS) [26] showed that almost 40% of cases enacted an aggressive behavior and that approximately half of these were physically violent [27]. A very recent survey promoted by the UK National Health System [24] using ad hoc developed measures and existing instruments altered to fit the research intents found that the average number of aggressive incidents in mental health/learning disability trusts was over three times the average for all trusts.

According to a prospective study [28] exploring aggressiveness with the Overt Aggression Scale (OAS) [29], in nine French hospitals on involuntary psychiatric inpatients, 79% had been violent, either verbally or physically.

The situation seems comparable in Germany, where, according to a survey on four institutions, 78.7% of the interviewed professionals working in psychiatric inpatients settings reported physical aggression while 96.7% reported verbal forms of aggression from patients in the 12 months prior to the study [30].

Similarly, a Polish study [31] comparing acts of violence in psychiatric and nonpsychiatric settings showed that the overall level of aggression was significantly higher in psychiatric wards. Verbal aggression and screaming were experienced by 100% of psychiatric nurses and physical attacks by 79.5% during the previous year.

An Irish study [32] on patients with first episode psychosis using the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) [33] found physical violence rates of 29% and verbal aggression rates of 36%.

A 1-year investigation on all patients admitted to two short-term psychiatric units in Norway, using the V-Risk-10 scale [34], revealed lower figures: 9% of 1017 patients were aggressive. Of the total number of episodes, 22% were verbal, 38% physical, and 40% both verbal and physical [35].

A Danish study, using the Brøset Violence Checklist (BVC) [36] as a predictor of both verbal and physical aggression risk in 15 psychiatric wards over a period of 3 months, registered very heterogeneous results, with risks for aggressive episodes varying from 0.1 (i.e., one expected violent episode for a patient observed in 1000 shifts) to 14.7% (147 expected violent episodes for a patient observed in 1000 shifts) [37].

In Italy, a questionnaire-based retrospective study [25] showed that 91.5% of the mental health professionals involved in the research reported that they had been victims of one or more episodes of aggressions in the previous year. Specifically, 90.8% reported verbal aggression, 44.5% physical aggressions, and 21.3% were victims of injuries.

The prevalence of aggression per patient was examined, using the Staff Observation Aggression Scale (SOAS) [38], in another Italian study of 1534 patients admitted to a psychiatric unit [39]. Of these, 116 resulted responsible for 329 aggressive episodes (prevalence of aggression = 7.5%; 2.8% incidents/patient). Thirteen episodes were verbal (4%), while the reminders were represented by physical assaults of different seriousness: 266 “simple” physical assaults (80.9%), 40 assaults by using objects 40 (12.1%), and 10 dangerous assault 10 (3%). These results were confirmed in a further 7-year follow-up study [40]. Similar findings were presented in a multicenter Italian study involving 1324 inpatients, of whom 10% showed a verbally hostile behavior or aggression toward objects and 3% were physically assaultive toward others [41].

Aggression in Nonpsychiatric Settings

Interest in understanding how to deal with aggressive behavior in nonpsychiatric settings has increased over time.

International data on emergency departments (EDs) indicate that 25 to 80% of healthcare staff experience physical aggression at least once and nearly 100% is subjected to verbal aggression during their career [42]. Many factors contribute to aggression in EDs, such as poor staffing, lack of privacy, overcrowding, and availability of nonsecured equipment that can be used as weapons by patients [43••].

A review which undertook an international perspective [44] highlighted that modalities of aggression vary with different cultural and social contexts: for instance, patients presenting with weapons in the EDs are more frequent in countries where the acquisition of a weapon is legal, while it is much less likely in others, where obtaining a weapon is more difficult, such as the UK, where in contrast verbal threats, or intimidation, appear significant.

Violence in hospital is indeed considered critical in the UK, where National Health System statistics showed that there were almost one and a half million total reported assaults on staff in 2016 [45].

In Switzerland, a multiple regression analysis study evidenced that besides EDs, a high verbal and physical aggression hazard was present in intensive care units, recovery units, anesthesia, intermediate care, and step-down units [46]. A recent investigation carried out in Norway in ten emergency clinics over 1 year [47], using the Staff Observation of Aggression scale–Revised (SOAS-R), registered a total of 320 aggressive incidents, 60% of which were severe. Verbal aggression episodes accounted for 31.6% of all incidents, threats for 24.7%, and physical aggressions for 43.7%.

In geriatric settings, a Swedish study on 309 patients with dementia evidenced that nearly 32% of patients had shown a physical aggressive behavior in the preceding week. Violent patients were more likely to have impaired speech, difficulties in understanding verbal communication, and prescribed analgesics and antipsychotics [48]. In a German survey using SOAS-R, 73 and 94% out of 585 geriatric professionals had received respectively physical and verbal aggressions in the previous 12 months [49].

In an Italian national cross-sectional survey [50], 76% of 816 EDs nurses reported verbal abuse from patients, 15.5% both physical and verbal aggression, and 0.61% only physical abuse in the year prior to data collection. Rudeness and bad manners (94.0%), the threat of legal action (77.4%), and screaming or shouting (77.0%) were the most frequent verbal form of aggression. The most frequently reported physical aggressions were pulling/grabbing (50.4%), pushing (40.3%), and punching/slapping (36.4%). Arms (60.9%), chest (33.6%), and face (28.1%) were the most harmed parts of the body. Another Italian study, with a retrospective design, collected data from EDs and Acute Psychiatric Units staff, coming to similar findings [51], while a cross-sectional study on 700 nurses of several Italian health departments showed that 49% of them had experienced at least one episode of aggression in the previous year, 82% of which was verbal [52].

In a cross-sectional retrospective Polish study [31], 89.6% of nonpsychiatric nurses reported verbal aggression by patients in the previous year, while physical attacks were experienced by 20.6%. Thirty percent reported screaming from patients on a weekly basis, and over 16% repeated physical attacks. Similar findings leaded another extensive Polish study on more than 1600 healthcare workers, who declared both verbal and physical aggression by patients in several healthcare settings [53].

In general medical units, a condition known as excited delirium (ExD) frequently escalates to violent enactments [54]. ExD is a trans-diagnostic neuropsychiatric condition characterized by a cluster of behaviors including bizarreness, aggression, agitation, ranting, hyperactivity, paranoia, panic, surprising physical strength, hyperthermia, respiratory arrest, and not infrequently death [55]. It is the result of substance intoxication, psychiatric illness, alcohol withdrawal, head trauma, or a combination of these [56, 57].

Risk Factors

The authors of a large longitudinal study carried out in Sweden found that subjects with mental disorders were approximately 4 times more likely than their healthy siblings to perpetrate violence [58••]. However, identifying the factors at the base of violent behaviors in this population is a difficult undertaking, given the wide range of potentially mediating variables.

For clarity reasons, we will divide the risk factors for aggression in psychiatric patients into “internal” and “external” factors [59•] (Table 1).

Finally, we will account for recent research focusing on the neurobiological correlates of aggression [60, 61].

Internal Factors

Psychiatric Diagnosis

According to several studies [62,63,64,65], having a mental disease with severe symptoms is associated with a higher probability of any form of aggressive behavior. Recent investigations identify schizophrenia, cognitive impairment, anxiety, acute stress reaction, suicidal ideation, along with poor insight, personality disorders, impulsivity, and psychopathy as the clinical factors with the strongest empirical evidence for association with violence [66, 67]. In nonpsychiatric hospital setting, aggression, especially in a physical form, appears mostly perpetrated by patients affected by dementia, mental retardation, or other psychiatric disorders and by drug and substance abuse [68].

An extensive Swedish study using nationwide registers analyzed data on 250,419 psychiatric patients, showing that the risks of violence perpetration varied across diagnoses, with higher risks among patients with schizophrenia than among subjects with depressive disorders [58••]. However, according to another Swedish population-based longitudinal study, the risk of physical aggression was higher in subjects with depression than in the general population [69].

A Danish systematic study found an increased risk of aggressive acts associated with mental disorders along the entire diagnostic spectrum, with a similar effect size for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression [70].

Italian clinical studies showed a direct correlation between symptoms of acute psychosis and the occurrence of aggressive behaviors, with the presence of disorientation, motor hyperactivity, hostility-suspiciousness, grandiosity and borderline and passive-aggressive personality traits predicting a change for the worse in aggressive behavior, from verbal to physical [68, 71, 72••], while good metacognition and self-reflectivity appeared as protective factors [72••]. A recent retrospective Italian study found that clinical diagnoses with higher scores at the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) were antisocial and borderline personality disorders, suicidality, mental retardation, and dementia [72••].

Another recent Italian cohort study [73] investigated the relationship between clinical and neuropsychological factors with risk of aggression in inpatients with schizophrenia. Physically aggressive patients showed a higher number of compulsory admissions, higher anger, and less negative symptoms as compared to non-aggressive patients. Aggressive patients performed better on executive and motor tasks probably due to lower negative psychotic symptoms. Negative symptoms also predicted fewer verbal aggressions at 1-year follow-up.

A recent Greek study suggested that a distinction should be done between aggressivity related to the core positive symptoms of schizophrenia and that emerging from independent antisocial personality traits, along with alcohol consumption [74].

Irish and UK observational studies [27, 32] evidenced that patients at first episode psychosis had an even higher risk of violent behavior when involuntarily treated, with a diagnosis of mania and the presence of manic symptoms.

An increased risk for aggressive behaviors has been associated with the concomitant presence of a complex psychiatric condition and the use of antiepileptic drugs in patients with epilepsy [75].

Recently, a role of both short sleep duration and night-to-night variations has been suggested in increased aggression among patients in psychiatric intensive care units [76].

Sociodemographic Factors

Research, however, seems to suggest that mental disorders may not be necessary nor sufficient causes of violence and that, for psychiatric patients as for the general population, sociodemographic and economic factors are contributors to aggressive behaviors [16, 69, 72••, 77•, 78,79,80,81,82].

Male and younger patients are indicated as the most frequent perpetrators of aggressive enactments [66, 72, 83]. Nonetheless, a registry-based study carried out in Denmark showed that, while any form of aggression was much higher in men, the relative impact of mental disorders on risk of aggressive behaviors was stronger in women [69].

An Italian retrospective study [72••] on 400 patients evidenced that while mean MOAS scores were negatively correlated with age of patients, they resulted significantly higher in unemployed vs employed patients, as well as in patients living in indigence, in particular homeless. In addition, male and female single patients showed significantly higher mean MOAS scores compared to patients who were married, while no significant correlation with education and ethnicity was found.

These results are confirmed by a study which gathered data of 522 inpatients from 84 mental health units in South England. Physically aggressive patients typically were younger and more likely to live alone, indicating poor availability of social support [22].

A recent Czech clinical study [84] confirmed a negative correlation between employment and aggressiveness among patients with a psychotic disorder.

History of Aggressions

Patients with severe mental disorders and a history of enacted aggressions are usually considered at high risk of recidivism and poor compliance [16].

A recent cohort Italian study [73] compared a sample of patients with schizophrenia and a history of physical aggression to patients with schizophrenia matched by age, gender, and alcohol abuse but without such a history. During a 1-year follow-up, patients with a history of aggression resulted more likely to be violent.

Another Italian prospective study, comparing never aggressive with verbally, physically, and sexually aggressive male psychiatric patients, found that the latter had displayed an increased number of aggressive behaviors in the previous 2 years [71].

On the same line, a UK study on 522 psychiatric inpatients evidenced that a history of violence was present at higher rates among those who enacted aggression of several forms during hospitalization [22]. However, in an Italian study, inpatients with a history of violence did not show at MOAS higher rates of aggressiveness compared to patients without such a history [85]. Interestingly, a second part of the study, exploring patients’ behavior in the community, found that subjects with a lifetime history of violence engaged in more aggressive enactments than patients without [86]. The Authors speculated that when adequate treatment and management are available, a history of physical aggressiveness does not link with an increased risk of violence.

History of Childhood Abuse and Neglect

In psychiatric patients, as well as in the general population, aggressive conducts can be related to traumatizing life events, including childhood abuse and neglect [77•, 87].

The association between a history of childhood abuse and a higher risk of aggressive behavior and delinquency in the adult age (“the cycle of violence”) has been known for a long time [88], although empirical evidence emerged only more recently [89,90,91,92].

A cross-sectional UK study, comparing male mental health patients with a history of childhood trauma to matched patients without childhood traumatization, found that the formers were 2.8 more likely to commit physical aggressions across the life span [93].

A French study [87] evaluating five different forms of childhood and adolescence neglect and abuse in schizophrenic inpatients with a history of violence found that 46% experienced at least one form of abuse and/or neglect during childhood and 21% experienced more than two forms of abuse and/or neglect. The most frequent forms of maltreatment were physical abuse (39%) and emotional neglect (18%), followed by physical neglect (14%) and sexual and emotional abuse (11%). In addition, a large proportion of patients (43%) had lost a parent in their childhood, 42% of whom died from an aggression.

A retrospective study carried out in the Czech Republic [84] showed, using multiple regression, that childhood physical or sexual maltreatment and recent victimization robustly increased the risk of aggression in patients with psychosis.

Another recent Norwegian study [94] using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [95] found significant differences in childhood exposure to both abuse and neglect: aggressive psychiatric patients showed higher CTQ scores than non-aggressive patients, and both patient groups had higher scores than healthy controls.

Drug Abuse

The role of substance abuse on aggressive enactments in psychiatry has been well articulated and described as one of the most robust clinical findings, with data indicating a doubling of the risk of physical violence through multiple pathways, including substances increasing psychotic symptoms, and a shared risk factors for psychosis and substance abuse [18••, 96••].

A recent review of 27 studies correlated substance abuse with the most severe form of aggressions in patients with schizophrenia [77•]. In a meta-analysis, moreover, substance abuse was associated with aggressions of any severity in patients at their first psychotic episode [97].

The impact of these findings is better understood when considering that, in Europe, 30–50% of people with a severe mental illness also have problems with substance use [98].

On this line, a recent Swiss cohort study on an early psychosis population of 265 patients found that the earlier the cannabis abuse started, the higher was the risk of physical aggressiveness [99].

An extensive registry-based longitudinal Swedish research, involving 250,419 patients, found that risk of aggression was the highest in subjects with concomitant substance use disorders [58••].

A population-based epidemiological study carried out in Denmark [69] confirmed that patients with comorbid mental illness and substance abuse increased the risk of physically aggressive enactments especially among women.

According to an abovementioned Italian study on psychiatric patients [72••], mean MOAS scores for both verbal and physical aggression resulted higher in the alcohol and cannabinoid abusers, while heroine abusers did not show increased scores.

Another study carried out in South England showed that illicit substance use was present in higher rates among verbally and physically aggressive inpatients, with no other clinical factors consistently related to inward aggressive behavior [22].

Alcohol intoxication, substance abuse, and mental illness were also indicated by 220 physicians and nurses as clinical factors for workplace violence in a Cypriot study [100],

Similarly, a retrospective Czech study estimated drug and alcohol use as predictors for physically assaultive behavior both in psychiatric inpatients and controls [84].

Cannabis abuse has been confirmed as a risk factor for violence in a Swiss investigation on patients with early psychosis. The combination of cannabis use, impulsivity, lack of insight, and non-adherence to treatment furtherly increased the risk [99].

A nationwide Italian research individuated among the major risks of physical aggression in EDs, drunkenness (44.6%), and being under the effect of illicit drugs (28.6%) [50].

External Factors

Contextual Factors

Starting from 1990s, literature has been uncontroversial in stating that interpersonal factors are among the most important external determinants of aggressive incidents in general hospital, with ineffective staff-patient relationships, aversive stimulations, and resulting feelings of powerlessness as dramatic precipitants of aggressive acting-outs [22, 67, 78, 101, 102].

A review specifically focused on staff-patient relationship [103] showed that a negative “staff-patient interaction” was the most frequent antecedent overall, precipitating 39% of all aggressive incidents. These finding were confirmed by a review on patients’ perception of factors that ignited a violent reaction toward the staff. Patients recognized in the experience of being ignored and in perception of staff behavior as custodial two major factors triggering aggressive reactions [104].

In Italy, high patient/nurse ratios have been indicated as another significant correlate of an increased risk of violence in general hospital [105], along with long waiting, overcrowding, and feeling of lack of caring [50].

Studies conducted on Norwegian and Irish staff individuated long waiting, involuntary examinations, and poor communication as major contributors to aggressive enactments in EDs [47, 106].

Conversely, a study conducted on English nurses indicated in a positive nurse-patient relationship, the most protective factor against risk of inward violence [107]. In addition, an interesting Italian research found that staff members’ avoidant attachment correlated positively with emotionally aggressive behaviors by patients, while a secure attachment style correlated negatively with both verbally and physically aggressive behaviors. [108•].

No “week-end effect,” in terms of significant variations in the incidence of aggressions on different days of the week due to changes in availability of personnel and services, was suggested in a large study using electronic health records of inpatients of a psychiatric hospital in England [109].

Regarding the physical structure of hospital wards, English and Swedish retrospective studies showed that in psychiatric wards with a distress reducing design (e.g., optimal light, privacy, common areas with ample spaces, and a garden), the number of physical restraints and compulsive injections was reduced [111, 110].

In recognizing the clinical environment as a factor that influences violent incidents, the Royal College of Psychiatrists in UK has developed guidelines to provide directions on the environmental and relational elements that trigger or reduce aggressive behaviors [112].

Neurobiological Theories of Aggression

Studies on the neurobiology of aggression have proposed possible alterations in brain areas also involved with the formation of psychotic symptoms and affective regulation, including frontotemporal circuitry, the amygdala-orbitofrontal system, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus [7, 113, 114••, 115••, 116].

Multiple lines of evidence have shown a dysfunction in the serotonin (5-HT) system in aggressive and in mentally ill subjects, with reduced 5-HT activity associated with depression as well as with impulsive aggression [117, 118].

The contributing role of steroid hormones is another focus of recent research. In a study of a multiple regression model including abuse/neglect history, psychopathy, and impulsivity, baseline cortisol explained 58% of the variance in trait aggression and 26% of the variance in state aggression. The study seems to support the hypothesis that abuse/neglect experiences predict a reduced hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis reactivity, suggesting that a history of child maltreatment, psychopathy, and an impaired HPA-axis reactivity might act together to generate a confluence over aggressive behavior [118].

Recently, pathological appetitive aggression (to be distinguished from defensive one) has been hypothesized to result from an excessive activation of evolutionary conserved reward circuits, also mediating the rewarding effects of addictive drugs [119]. The authors suggest that inappropriate appetitive aggression shares core features with addiction: aggression is often sought despite adverse consequences, and relapse rates among aggressive offenders are as high as relapse rates in drug addiction.

Several genes have been investigated to explore a possible correlation with aggressive behavior. The most intensively studied is the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene allocated on chromosome 22. COMT is involved in the metabolism of dopamine, a key neurotransmitter in schizophrenia pathophysiology. A meta-analysis involving 2370 individuals showed that male patients with schizophrenia who carried the low-activity methionine allele in the COMT gene had an increase in aggression risk by approximately 50% compared with homozygous valine patients [120]. A more recent Swedish cohort study was in line with the hypothesis that COMT genotypes modify the sensitivity to environment that confers either risk (methionine allele) or protection (valine allele) for aggressive behavior [121].

Recent data, evaluating the history of ExD across time, suggest a possible genetic disorder leading to dysregulated central dopamine transporter function that may be a precipitating cause of the condition of excitement and aggressiveness, as well as sudden death because of loss of autonomic function, progressing to cardiorespiratory collapse [122].

Discussion

In this review, we have examined, within a quite complex and controversial literature, the phenomenon of aggression in European hospital settings. Our findings indicate the existence of some differences in rates of aggressive episodes among European countries. This can be due to organizational and environmental differences, such as the extension of teamwork or staff isolation and the characteristics of services and patient/staff ratios, or to differences in reporting aggression, rather than to real clinical differences.

In general, there is an agreement to consider that the interplay of different variables intervenes in determining the risk of aggressive behavior in psychiatric patients. The relationship between mental illness and aggression appears mediated by a combination of clinical, individual, and contextual risk factors, with drug abuse as a trans-dimensional variable which deserves particular attention and with an early age onset of drug abuse as an even higher risk of later occurrence of physically aggressive behavior. This could be explained with the impact of drugs on the neurobiological balance during adolescence, a crucial period for brain maturation.

Among sociodemographic variables, younger age appears independently correlated to an increased risk of aggression, suggesting a reduced capacity of emotional regulation, due either to the young age itself or to a higher acuity of symptom profile at the onset of psychosis [22].

The association between a history of childhood abuse and neglect and an increased risk of aggressive behavior in psychiatric patients has been highlighted in several European studies, confirming that the “cycle of violence” displays a transgenerational pattern.

It has also been pointed out how ward relational factors can often precipitate aggressive incidents. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that ward architectural inadequacies that limit the possibility of patients to seek privacy, regulate relationships, and reduce stressors such as noise and arguments play a role in increasing levels of aggressiveness in hospitals.

In addition, research suggests a possible existence of neurobiological correlates of aggression in psychiatry.

Literature data show that the consequences of aggression are wide reaching, both for victims and actors. Victims of physical aggression—leaving aside physical damage—can report a vast array of psychological consequences, whose seriousness ranges from adjustment symptoms up to post-traumatic stress disorders [123•, 124]. Verbal aggression has been found to produce angst, depression, and other emotional distress, with repercussions on morale, professional replacement, quality of care, and patient recovery processes [125,126,127].

It has been hypothesized that patients with severe mental illness may lack skills to resolve interpersonal conflicts and consequently resort to physical violence [84]. If this hypothesis was confirmed, effective social skills training interventions could reduce aggressive enactments as well as victimization experiences.

On these premises, greater importance should be given to initiatives aimed at improving prevention, early recognition, and management of aggression in general hospital.

Recently, an updated version of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline for short-term management in psychiatric settings has been developed by a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals, patients with a personal experience of aggressive behavior, their caregivers, and guideline methodologists [43••].

However, despite the growth in legislation and in the number of Health and Safety Authorities in various European member states [128], a lack of unifying procedures and standards emerges pertaining to ward safety and security in psychiatric and general hospitals [129].

Conclusions

This review has some limitations. The first arises from the research design itself. Though this work explored different factors in the area, the studies included are heterogeneous and this review did not intend to categorize them depending on their design, methods, and primary outcomes; therefore, no definitive conclusion about associations between factors and risk of aggression can be made. Another limitation partially derives from the nature of both the literature available (which did not allow a more precise differentiation among countries, inpatients and medical environments) and the topic (which does not lend itself to more rigorous research approaches, such as randomized controlled trials).

Nonetheless, we believe that this review can be a valuable contribution to a better delineation of the phenomenon of aggression in European inpatient hospital settings. It also highlights the need to take a commitment both in using the predictive variables to create guidelines and procedures for prevention of aggressive behavior and in improving strategies to manage aggression in the general hospital.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, Geddes JR, Grann M. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000120.

Grassi L, Mitchell AJ, Otani M, Caruso R, Nanni MG, Hachizuka M, et al. Consultation-liaison psychiatry in the general hospital: the experience of UK, Italy, and Japan. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(6):44.

Mullen PE. A reassessment of the link between mental disorder and violent behaviour, and its implications for clinical practice. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(1):3–11.

Marzuk PM. Violence, crime, and mental illness: how strong a link? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(6):481–6.

Noffsinger SG, Resnick PJ. Violence and mental illness. Curr OpinPsychiatry. 1999;12:683–7.

• Varshney M, Mahapatra A, Krishnan V, Gupta R, Deb KS. Violence and mental illness: what is the true story? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(3):223–5 Article discussing the relationship between violence and mental illness. What influences public perception, implications from a public health perspective and current evidence.

•• Pompili E, Carlone C, Silvestrini C, Nicolò G. Focus on aggressive behaviour in mental illness. Riv Psichiatr. 2017;52(5):175–9 Review, based on a selective search of 2010–2016 pertinent literature on PubMed, that summarize information from original articles, reviews, and book chapters about aggression and psychiatric disorders, discussing neurobiological basis and therapy of aggressive behavior.

Rubio-Valera M, Luciano JV, Ortiz JM, Salvador-Carulla L, Gracia A, Serrano-Blanco A. Health service use and costs associated with aggressiveness or agitation and containment in adult psychiatric care: a systematic review of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:35.

Estryn-Behar M, van der Heijden B, Camerino D, Fry C, Le Nezet O, Conway PM, et al. Violence risks in nursing–results from the European ‘NEXT’ study. Occup Med. 2008;58(2):107–14.

Al Ubaidi B. Workplace violence in healthcare: an emerging occupational hazard. Bahrain Medical Bulletin. 2018;40(1):43–5.

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA) European Risk Observatory Report. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.2010. (Online) Available from: https://osha.europa.eu/en/about-eu-osha/what-we-do/european-riskobservatory

Lundström M. Aggression – challenge and fatigue. Nurses’exposure and experiences related to aggression in sheltered accommodations for people with intellectual disabilities. Dissertations, new series. 2006.No.2032, Department of Nursing. Umeå University. Sweden. .

Flannery RB Jr, Wyshak G, Flannery GJ. Characteristics of international staff victims of psychiatric patient assaults: review of published findings, 2000-2012. Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(4):397–404.

Edward KL, Stephenson J, Ousey K, Lui S, Warelow P, Giandinoto JA. A systematic review and meta-analysis of factors that relate to aggression perpetrated against nurses by patients/relatives or staff. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(3–4):289–99.

•• D'Ettorre G, Pellicani V. Workplace Violence Toward Mental Healthcare Workers Employed in Psychiatric Wards. Saf Health Work. 2017;8(4):337–42 Review of publications in PubMed and Web of Science on articles on the concern of patient violence against health care workers employed in psychiatric inpatient wards, in the past 20 years. This review analyzes four main topics: risk assessment, risk management, occurrence rates, and physical/nonphysical consequences.

Iozzino L, Ferrari C, Large M, Nielssen O, de Girolamo G. Prevalence and risk factors of violence by psychiatric acute inpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128536.

Spector PE, Zhou ZE, Che XX. Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: a quantitative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(1):72–84.

•• Flannery RB, Flannery GJ. International Review of Precipitants to Patient Assaults on Staff, 2013–2017. Psychiatr Q. 2018;89(2):497–503 Review on the literature on precipitants to patient assaults from 2013 to 2017.

Arnetz BB. Physicians’ view of their work environment and organisation. Psychother Psychosom. 1997;66:155/162.

Lawoko S, Soares JJF, Nolan P. Violence towards psychiatric staff: a comparison of gender, job and environmental characteristics in England and Sweden. Work & Stress. 2004;18(1):39–55.

Bowers L, Douzenis A, Galeazzi GM, Forghieri M, Tsopelas C, Simpson A, et al. Disruptive and dangerous behaviour by patients on acute psychiatric wards in three European centres. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40(10):822–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0967-1 Epub 2005 Sep 22.

Renwick L, Stewart D, Richardson M, Lavelle M, James K, Hardy C, et al. Aggression on inpatient units: clinical characteristics and consequences. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2016;25(4):308–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12191 Epub 2016 Feb 19.

Johansen IH, Baste V, Rosta J, Aasland OG, Morken T. Changes in prevalence of workplace violence against doctors in all medical specialties in Norway between 1993 and 2014: a repeated cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017757.

Cheng S, Dawson J, Thamby J. How do aggression source, employee characteristics and organisational response impact the relationship between workplace aggression and work and health outcomes in healthcare employees? A cross-sectional analysis of the National Health Service staff survey in England. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035957.

Bizzarri JV, Piacentino D, Kotzalidis GD, Moser S, Cappelletti S, Weissenberger G, et al. Aggression and violence toward healthcare Workers in a Psychiatric Service in Italy: a retrospective questionnaire-based survey. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(4):299–305.

Jablensky A, et al. Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study. Psychological medicine, Suppl. 1992;20.

Dean K, Walsh E, Morgan C. Aggressive behaviour at first contact with services: findings from the AESOP first episode psychosis study. Psychol Med. 2007;37(4):547–57.

Rothärmel M, Poirier MF, Levacon G. Association between the violence in the community and the aggressive behaviors of psychotics during their hospitalizations. Encephale. 2017;43(5):409–15.

Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, Endicott J, Williams D. The overt aggression scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(1):35–9. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.143.1.35.

Franz S, Zeh A, Schablon A, Kuhnert S, Nienhaus A. Aggression and violence against health care workers in Germany--a cross sectional retrospective survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:51 Published 2010 Feb 25.

Merecz D, Rymaszewska J, Mościcka A, Kiejna A, Jarosz-Nowak J. Violence at the workplace--a questionnaire survey of nurses. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21(7):442–50.

Keane S, Szigeti A, Fanning F, Clarke M. Are patterns of violence and aggression at presentation in patients with first-episode psychosis temporally stable? A comparison of 2 cohorts. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2019;13(4):888–94.

Coccaro EF, Harvey PD, Kupsaw-Lawrence E, Herbert JL, Bernstein DP. Development of neuropharmacologically based behavioral assessments of impulsive aggressive behavior. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1991;3(2):S44–51.

Roaldset JO, Hartvig P, Bjørkly S. V-RISK-10: validation of a screen for risk of violence after discharge from acute psychiatry. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(2):85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.04.002 Epub 2010 Jul 8.

Hartvig P, Roaldset JO, Moger TA, Østberg B, Bjørkly S. The first step in the validation of a new screen for violence risk in acute psychiatry: the inpatient context. European Psychiatry. 2011;26(2):92–9.

Almvik R, Woods P. The brøset violence checklist (BVC) and the prediction of inpatient violence: Some preliminary results. Psychiatric Care. 1998;5(6):208–11.

Hvidhjelm J, Sestoft D, Skovgaard LT, Rasmussen K, Almvik R, Bue BJ. Aggression in psychiatric wards: effect of the use of a structured risk assessment. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2016;37(12):960–7.

Morken T, Baste V, Johnsen GE, Rypdal K, Palmstierna T, Johansen IH. The staff observation aggression scale - revised (SOAS-R) - adjustment and validation for emergency primary health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):335.

Grassi L, Peron L, Marangoni C, Zanchi P, Vanni A. Characteristics of violent behaviour in acute psychiatric in-patients: a 5-year Italian study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104:273–9.

Grassi L, Biancosino B, Marmai L, Kotrotsiou V, Zanchi P, Peron L, et al. Violence in psychiatric units. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:698–703.

Biancosino B, Delmonte S, Grassi L, Santone G, Preti A, Miglio R, et al. Violent behavior in acute psychiatric inpatient facilities: a national survey in Italy. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009 Oct;197(10):772–82.

Pourshaikhian M, Gorji HA, Aryankhesal A, Khorasani-Zavareh D, Barati A. A systematic literature review: workplace violence against emergency medical services personnel. Arch Trauma Res. 2016;5:213–24.

•• British Psychological Society, The Royal College of Psychiatrists, National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Violence and Aggression: Short-Term Management in Mental Health, Health and Community Settings: Updated edition. London: British Psychological Society; 2015. NICE guidelines 2015. Guidelines covering the short-term management of violence and aggression in adults, young people,and children and aiming to safeguard both staff and people who use services by helping to prevent violent situations and providing guidance to manage them safely when they occur. pdf1837264712389 2015

Ferns T. Violence in the accident and emergency department--an international perspective. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2005;13(3):180–5.

NHS Protect. Reported physical assaults on NHS staff figures. Physical assaults against NHS staff.2015/16, http://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/Documents/SecurityManagement/Reported_Physical_Assaults_2015–16.

Hahn S, Müller M, Hantikainen V, Kok G, Dassen T, Halfens RJ. Risk factors associated with patient and visitor violence in general hospitals: results of a multiple regression analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(3):374–85.

Johnsen GE, Morken T, Baste V, Rypdal K, Palmstierna T, Johansen IH. Characteristics of aggressive incidents in emergency primary health care described by the Staff Observation Aggression Scale - Revised Emergency (SOAS-RE). BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):33 Published 2020 Jan 13.

Isaksson U, Graneheim UH, Åström S, Karlsson S. Physically violent behaviour in dementia care: characteristics of residents and management of violent situations. Aging Ment Health. 2011 Jul 1;15(5):573–9.

Schablon A, Wendeler D, Kozak A, Nienhaus A, Steinke S. Prevalence and Consequences of Aggression and Violence towards Nursing and Care Staff in Germany-A Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):1274 Published 2018 Jun 15.

Ramacciati N, Gili A, Mezzetti A, Ceccagnoli A, Addey B, Rasero L. Violence towards emergency nurses. Te 2016 Italian national survey: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Nursing Management. 2016:1–14.

Cannavò M, La Torre F, Sestili C, La Torre G, Fioravanti M. Work related violence as a predictor of stress and correlated disorders in emergency department healthcare professionals. Clin Ter. 2019;170(2):e110–23.

Zampieron A, Galeazzo M, Turra S, Buja A. Perceived aggression towards nurses: study in two Italian health institutions [published correction appears in J Clin Nurs. 2011 Jun;20(11–12):1796]. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(15–16):2329–41.

Kowalczuk K, Krajewska-Kułak E. Patient aggression towards different professional groups of healthcare workers. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017;24(1):113–6.

Baldwin S, Hall C, Blaskovits B, Bennell C, Lawrence C, Semple T. Excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): Situational factors and risks to officer safety in non-fatal use of force encounters. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2018;60:26–34.

Samuel E, Williams RB, Ferrell RB. Excited delirium: consideration of selected medical and psychiatric issues. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:61–6.

Vilke GM, Bozeman WP, Dawes DM, Demers G. Wilson MP excited delirium syndrome (ExDS): treatment options and considerations. J Forensic Legal Med. 2012;19(3):117–21.

Gerold KB, Gibbons ME, Fisette RE Jr. Alves D.J review, clinical update, and practice guidelines for excited delirium syndrome. Spec Oper Med. 2015 Spring;15(1):62–9.

•• Sariaslan A, Arseneault L, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, Fazel S. Risk of Subjection to Violence and Perpetration of Violence in Persons With Psychiatric Disorders in Sweden. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;4275 Extensive longitudinal study exploring the risk of victimization and perpetration of violence by patients with a psychiatric disorder in Sweden, compared with the general population.

• O’Rourke M, Wrigley C, Hammond S. Violence within mental health services: how to enhance risk management. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2018;11:159–67 This paper has the aim to present best practice in risk management within mental health services by exploring the prevalence of violence, the nature of risk and by highlighting lessons learned and guidance published on safer services. The article presents ways to enhance risk management in mental health care and reflects on current health care practices.

Hoptman MJ. Impulsivity and aggression in schizophrenia: a neural circuitry perspective with implications for treatment. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(3):280–6.

Rosell DR, Siever LJ. The neurobiology of aggression and violence. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(3):254–79.

Raboch J, Kalisová L, Nawka A, Kitzlerová E, Onchev G, Karastergiou A, et al. Use of coercive measures during involuntary hospitalization: findings from ten European countries. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(10):1012–7.

Flannery RB Jr. Repetitively assaultive patients: review of published findings, 1978–2001. Psychiatry Q. 2002;73:229–37.

Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J. Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur violence risk assessment study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:566–72.

de Girolamo G, Carrà G, Fangerau H, Ferrari C, Gosek P, Heitzman J, et al. European violence risk and mental disorders (EU-VIORMED): a multi-centre prospective cohort study protocol. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):410. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2379-x.

Dack C, Ross J, Papadopoulos C, Stewart D, Bowers L. A review and meta-analysis of the patient factors associated with psychiatric in-patient aggression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(4):255–68.

D'Ettorre G, Pellicani V, Mazzotta M, Vullo A. Preventing and managing workplace violence against healthcare workers in Emergency Departments. Acta Biomed. 2018;89(4-S):28–36 Published 2018 Feb 21.

Amore M, Menchetti M, Tonti C, Scarlatti F, Lundgren E, Esposito W, et al. Predictors of violent behavior among acute psychiatric patients: clinical study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62(3):247–55.

Fazel S, Wolf A, Chang Z, Larsson H, Goodwin GM, Lichtenstein P. Depression and violence: a Swedish population study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):224–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215.

Stevens H, Laursen TM, Mortensen PB, Agerbo E, Dean K. Post-illness-onset risk of offending across the full spectrum of psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2015;45:2447–57.

Candini V, Ghisi M, Bianconi G, et al. Aggressive behavior and metacognitive functions: a longitudinal study on patients with mental disorders. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2020;19:36 Published 2020 Jun 3.

•• Mauri MC, Cirnigliaro G, Di Pace C, Paletta S, Reggiori A, Altamura CA, et al. Aggressiveness and violence in psychiatric patients: a clinical or social paradigm? CNS Spectr. 2019;24(5):564–73 Study assessing the severity of aggressive and violent behaviors in 400 patients admitted to a post-acute psychiatric service in Milan, from 2014 to 2016 and suffering from different psychiatric disorders. This study provides an evaluation on the possible correlation between epidemiologic and sociodemographic factors, clinical variables, and aggression and violence.

Bulgari V, Iozzino L, Ferrari C, Picchioni M, Candini V, De Francesco A, et al. de Girolamo G; VIORMED-1 group. Clinical and neuropsychological features of violence in schizophrenia: a prospective cohort study. Schizophr Res. 2017;181:124–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.016 Epub 2016 Oct 17.

Kristof Z, Kresznerits S, Olah M, Gyollai A, Lukacs-Miszler K, Halmai T, et al. Mentalization and empathy as predictors of violence in schizophrenic patients: comparison with nonviolent schizophrenic patients, violent controls and nonviolent controls. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:198–205.

Brodie MJ, Besag F, Ettinger AB, Mula M, Gobbi G, Comai S, et al. Epilepsy, antiepileptic drugs, and aggression: an evidence-based review. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(3):563–602.

Langsrud K, Kallestad H, Vaaler A, Almvik R, Palmstierna T, Morken G. Sleep at night and association to aggressive behaviour; patients in a psychiatric intensive care unit. Psychiatry Res. 2018 May;263:275–9.

• Rund BR. A review of factors associated with severe violence in schizophrenia. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(8):561–71 A literature review with the aim to identify external and clinical risk factors for serious violence in schizophrenia, in addition to considering the strength of the association between the factors assessed and severe violence.

Cornaggia C, Beghi M, Pavone F, Barale F. Aggression in psychiatry wards: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189:10–20.

Talevi D, Collazzoni A, Rossi A, et al. Cues for different diagnostic patterns of interpersonal violence in a psychiatric sample: an observational study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):196 Published 2020 May 1.

Swanson JW, Van Dorn RA, Swartz MS, Smith A, Elbogen EB, Monahan J. Alternative pathways to violence in persons with schizophrenia: the role of childhood antisocial behavior problems. Law Hum Behav. 2008;32(3):228–40.

Lejoyeux M, Nivoli F, Basquin A, Petit A, Chalvin F, Embouazza H. An Investigation of Factors Increasing the Risk of Aggressive Behavior among Schizophrenic Inpatients. Front Psychiatry. 2013;4:97 Published 2013 Sep 3.

Ferri P, Silvestri M, Artoni C, Di Lorenzo R. Workplace violence in different settings and among various health professionals in an Italian general hospital: a cross -sectional study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2016;9:263–75.

Szabo K, White C, Cummings S, Wang R. Inpatient aggression in community hospitals. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(3):223–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852914000820.

Černý M, Hodgins S, Kučíková R, et al. Violence in persons with and without psychosis in the Czech Republic: risk and protective factors. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2793–805. Published 2018 Oct 23. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S167928.

de Girolamo G, Buizza C, Sisti D, Ferrari C, Bulgari V, Iozzino L, et al. Candini V; VIORMED-1 group. Monitoring and predicting the risk of violence in residential facilities. No difference between patients with history or with no history of violence. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;80:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.05.010 Epub 2016 May 24.

Barlati S, Stefana A, Bartoli F, Bianconi G, Bulgari V, Candini V, et al. VIORMED-2 Group. Violence risk and mental disorders (VIORMED-2): A prospective multicenter study in Italy. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0214924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214924.

Bennouna-Greene M, Bennouna-Greene V, Berna F, Defranoux L. History of abuse and neglect in patients with schizophrenia who have a history of violence. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(5):329–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.01.008.

Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989;244(4901):160–6. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2704995.

Kozak RS, Gushwa M, Cadet TJ. Victimization and violence: an exploration of the relationship between child sexual abuse, violence, and delinquency. J Child Sex Abus. 2018;27(6):699–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2018.1474412 Epub 2018 May 24.

Johnson KL, Desmarais SL, Grimm KJ, Tueller SJ, Swartz MS, van Dorn RA. Proximal risk factors for short-term community violence among adults with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(7):771–7.

Krause-Utz A, Mertens LJ, Renn JB, Lucke P, Wöhlke AZ, van Schie CC, et al. Childhood maltreatment, borderline personality features, and coping as predictors of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2018;31:886260518817782. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518817782 Epub ahead of print.

Dean K, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Webb RT, Mortensen PB, Agerbo E. Risk of being subjected to crime, including violent crime, after onset of mental illness: A Danish national registry study using police data. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(7):689–96.

Bruce M, Laporte D. Childhood trauma, antisocial personality typologies and recent violent acts among inpatient males with severe mental illness: exploring an explanatory pathway. Schizophr Res. 2015;162(1–3):285–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2014.12.028 Epub 2015 Jan 28.

Storvestre GB, Jensen A, Bjerke E, Tesli N, Rosaeg C, Friestad C, et al. Childhood Trauma in Persons With Schizophrenia and a History of Interpersonal Violence. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00383.

Liebschutz JM, Buchanan-Howland K, Chen CA, Frank DA, Richardson MA, Heeren TC, et al. Childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ) correlations with prospective violence assessment in a longitudinal cohort. Psychol Assess. 2018;30:841–5. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000549.

•• Whiting D, Lichtenstein P, Fazel S. Violence and mental disorders: a structured review of associations by individual diagnoses, risk factors, and risk assessment. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;S2215–0366(20):30262–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30262-5 Epub ahead of print. Recent review summarizing evidence on the association between different mental disorders and violence, with emphasis on high quality designs and replicated findings.

Large MM, Nielssen O. Violence in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2011;125:209–20.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Co-morbid substance use and mental disorders in Europe: a review of the data, EMCDDA Papers, 2015. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Moulin V, Alameda L, Framorando D, Baumann PS, Gholam M, Gasser J, et al. Early onset of cannabis use and violent behavior in psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63(1):e78. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.71.

Vezyridis P, Samoutis A, Mavrikiou PM. Workplace violence against clinicians in Cypriot emergency departments: a national questionnaire survey. J Clin Nurs. 2014;24(9–10):1210–22.

Shepherd M, Lavender T. Putting aggression into context: an investigation into contextual factors influencing the rate of aggressive incidents in a psychiatric hospital. J Ment Health. 1999;8(2):159–70.

Powell G, Caan W, Crowe M. What events precede violent incidents in psychiatric hospitals? Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165(1):107–12.

Papadopoulos C, Ross J, Stewart D, Dack C, James K, Bowers L. The antecedents of violence and aggression within psychiatric in-patient settings. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(6):425–39.

Gudde CB, Olsø TM, Whittington R, Vatne S. Service users' experiences and views of aggressive situations in mental health care: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2015;8:449–62.

Felice E. The Socio-Institutional Divide: Explaining Italy’s Long-Term Regional Differences. The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 2018;49:1,43–70.

Angland S, Dowling M, Casey D. Nurses' perceptions of the factors which cause violence and aggression in the emergency department: a qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2014;22(3):134–9.

Trenoweth S. Perceiving risk in dangerous situations: risks of violence among mental health inpatients. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42(3):278–87.

• Berlanda S, Pedrazza M, Fraizzoli M, de Cordova F. Addressing Risks of Violence against Healthcare Staff in Emergency Departments: The Effects of Job Satisfaction and Attachment Style. BioMed Research International. 2019:1–12 Study exploring the impact of staff satisfaction with work and attachment style on aggressive enactments by patients in Emergency Departments.

Patel R, Chesney E, Cullen AE, Tulloch AD, Broadbent M, Stewart R, et al. Clinical outcomes and mortality associated with weekend admission to psychiatric hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(1):29–34.

Ulrich RS, Bogren L, Gardiner SK, Lundin S. Psychiatric ward design can reduce aggressive behavior. J Environ Psychol. 2018;57:53–66.

Jenkins O, Dye S, Foy C. A study of agitation, conflict and containment in association with changes in ward physical environment. Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care. 2015:27–35.

Perlini C, Bellani M, Besteher B, Nenadić I, Brambilla P. The neural basis of hostility-related dimensions in schizophrenia. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(6):546–51.

•• Fjellvang M, Grøning L, Haukvik UK. Imaging Violence in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Critical Discussion of the MRI Literature. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:333 Systematic review, of MRI studies of violence with schizophrenia, with the aim to critically discuss the promises and pitfalls of using this literature to understand violence in schizophrenia in clinical, forensic, and legal settings.

•• Widmayer S, Borgwardt S, Lang UE, Stieglitz RD, Huber CG. Functional Neuroimaging Correlates of Aggression in Psychosis: A Systematic Review With Recommendations for Future Research. Front Psychiatry. 2019;9:777 Systematic Review of studies reporting functional brain imaging correlates of aggression in patients with DSM or ICD diagnosis of affective or non-affective psychosis.

Widmayer S, Sowislo JF, Jungfer HA, Borgwardt S, Lang UE, Stieglitz RD, et al. Structural magnetic resonance imaging correlates of aggression in psychosis: a systematic review and effect size analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:217.

Manchia M, Carpiniello B, Valtorta F, Comai S. Serotonin dysfunction, aggressive behavior, and mental illness: exploring the link using a dimensional approach. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8(5):961–72.

Comai S, Bertazzo A, Vachon J, Daigle M, Toupin J, Côté G, et al. Tryptophan via serotonin/kynurenine pathways abnormalities in a large cohort of aggressive inmates: markers for aggression. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;70:8–16.

Gowin JL, Green CE, Alcorn JL 3rd, Swann AC, Moeller FG, Lane SD. The role of cortisol and psychopathy in the cycle of violence. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;227(4):661–72.

Golden SA, Shaham Y. Aggression addiction and relapse: a new frontier in psychiatry. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(1):224–5.

Singh JP, Volavka J, Czobor P, Van Dorn RA. A meta-analysis of the Val158Met COMT polymorphism and violent behavior in schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43423.

Tuvblad C, Narusyte J, Comasco E, Andershed H, Andershed AK, Colins OF, et al. Physical and verbal aggressive behavior and COMT genotype: sensitivity to the environment. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2016;171(5):708–18.

Mash DC. Excited Delirium and Sudden Death: A Syndromal Disorder at the Extreme End of the Neuropsychiatric Continuum. Front Physiol. 2016;7:435 Starting from the first description by the psychiatrist Luther Bell in institutionalized psychiatric patients the authors examine the several causes of ExD and its severe complications, including death.

Daniels JK, Anadria D. Experiencing and witnessing patient violence - an occupational risk for outpatient therapists? Psychiatr Q. 2019;90(3):533–41.

Andersen LP, Hogh A, Elklit A, Andersen JH, Biering K. Work-related threats and violence and post-traumatic symptoms in four high-risk occupations: short- and long-term symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2019;92(2):195–208.

Hankin CS, Bronstone A, Koran LM. Agitation in the inpatient psychiatric setting: a review of clinical presentation, burden, and treatment. J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(3):170–85.

Pelto-Piri V, Warg LE, Kjellin L. Violence and aggression in psychiatric inpatient care in Sweden: a critical incident technique analysis of staff descriptions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):362 Published 2020 Apr 26.

Ashton RA, Morris L, Smith I. A qualitative meta-synthesis of emergency department staff experiences of violence and aggression. International Emergency Nursing. 2018;39:13–9.

Flannery RB Jr. Characteristics of assaultive psychiatric inpatients: updated review of findings, 1995–2000. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2001;16:153–6.

Cowman S, Björkdahl A, Clarke E, Gethin G, Maguire J. European Violence in Psychiatry Research Group (EViPRG). A descriptive survey study of violence management and priorities among psychiatric staff in mental health services, across seventeen european countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):59 Published 2017 Jan.

Acknowledgments

The editors would like to thank Dr. Kamalika Roy for taking the time to review this manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Ferrara within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Rosangela Caruso, Fabio Antenora, Luigi Zerbinati, Bruno Biancosino, and Martino Belvederi Murri declare no conflict of interest.

Luigi Grassi has been scientific consultant for EISAI srl and Angelini and has royalties from Wiley, Springer, and Oxford University Press Inc. Michelle Riba has no conflict of interest related to this work but receives royalties from Springer, Guilford, Cambridge, American Psychiatric Press Inc., and Current Psychiatry Reports.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Complex Medical-Psychiatric Issues

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Caruso, R., Antenora, F., Riba, M. et al. Aggressive Behavior and Psychiatric Inpatients: a Narrative Review of the Literature with a Focus on the European Experience. Curr Psychiatry Rep 23, 29 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01233-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01233-z