Abstract

Objective

Chronic neck pain, a prevalent health concern characterized by frequent recurrence, requires exploration of treatment modalities that provide sustained relief. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the durable effects of acupuncture on chronic neck pain.

Methods

We conducted a literature search up to March 2024 in six databases, including PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library, encompassing both English and Chinese language publications. The main focus of evaluation included pain severity, functional disability, and quality of life, assessed at least 3 months post-acupuncture treatment. The risk of bias assessment was conducted using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool, and meta-analyses were performed where applicable.

Results

Eighteen randomized controlled trials were included in the analysis. Acupuncture as an adjunct therapy could provide sustained pain relief at three (SMD: − 0.79; 95% CI − 1.13 to − 0.46; p < 0.01) and six (MD: − 18.13; 95% CI − 30.18 to − 6.07; p < 0.01) months post-treatment. Compared to sham acupuncture, acupuncture did not show a statistically significant difference in pain alleviation (MD: − 0.12; 95% CI − 0.06 to 0.36; p = 0.63). However, it significantly improved functional outcomes as evidenced by Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire scores 3 months post-treatment (MD: − 6.06; 95% CI − 8.20 to − 3.92; p < 0.01). Although nine studies reported an 8.5%–13.8% probability of adverse events, these were mild and transitory adverse events.

Conclusion

Acupuncture as an adjunct therapy may provide post-treatment pain relief lasting at least 3 months for patients with chronic neck pain, although it is not superior to sham acupuncture, shows sustained efficacy in improving functional impairment for over 3 months, with a good safety profile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Neck pain, defined as pain extending from the upper cervical line to the level of the scapulae, may manifest as radiating discomfort affecting the head, trunk, and upper limbs [1]. This condition is the second leading cause of disability globally [2••], with an estimated 67% of individuals experiencing neck pain at some point in their lives [3]. Around 20% of these cases progress to chronic neck pain (CNP) [4], a pain persisting for over 3 months [5]. Individuals with sedentary occupations are particularly prone to CNP due to prolonged static postures, inadequate physical activity, and various workplace-related factors. CNP also frequently arises from traumatic events [6]. Notably, CNP imposes a significant public health and economic burden, with about 25% to 60% of patients experiencing pain for a year or longer after the initial episode [7•], a figure that rises to 60–80% among manual laborers [8].

Clinical guidelines typically advocate for oral medications and various interventional strategies for managing CNP. Despite the emphasis on physical therapy, adherence to prescribed exercises is often challenging, resulting in suboptimal outcomes. While physical therapy may offer temporary pain relief, the recurring nature of CNP necessitates frequent clinic visits for continued management, underscoring the limitations of current interventional strategies in providing long-term relief [9]. The conventional first-line treatment for CNP typically recommends the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, their use is marred by significant safety concerns, leading to the hospitalization of over 100,000 patients annually due to gastrointestinal complications associated with NSAID usage, as well as approximately 16,500 fatalities each year attributed to these adverse effects in the United States [10]. Given these concerns and the lack of substantial evidence for the sustained effectiveness of both pharmacological and physical interventions, there is a pressing need to explore treatment strategies for CNP that are more effective and safer with better sustained effects.

Many patients are dissatisfied with conventional treatments and seek complementary and alternative medicines (CAM). Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese therapeutic method that achieves healing through needle insertion, with a history of use exceeding 3,000 years in East Asia. It is characterized by minimal side effects and lasting efficacy, and has gained worldwide popularity, with over 14.01 million Americans having received acupuncture treatments [11, 12]. Acupuncture has demonstrated sustained effects in treating various diseases, suggesting that its enduring therapeutic efficacy may be advantageous in alleviating CNP [13, 14]. Current reviews have either overlooked the long-term effects of acupuncture in treating CNP or merely focused on its sustained benefits on pain relief, neglecting to comprehensively evaluate its post-treatment effects on functional improvement and quality of life enhancement [15,16,17]. Given the propensity of CNP to recur and persist, therapies exhibiting more pronounced sustained effects are worthy of patient recommendation. This meta-analysis aims to systematically assess the sustained effects of acupuncture on CNP, focusing on outcomes of pain, function, and quality of life, and safety assessment [18].

Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [19], and it was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under ID No. CRD42023403434. [20].

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Chinese Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Database, and the VIP Database for English and Chinese literature from their inception to March 2, 2024. The search terms included chronic neck pain (e.g., cervical pain, cervicodynia, myofascial pain syndrome, trachelodynia, and neck disorder), acupuncture (e.g., dry needling and electroacupuncture), and randomization (e.g., randomized controlled trials and clinical trials). Search strategies were formulated for different databases (supplementary data sheet S1). We manually screened the references of current reviews to obtain more relevant research.

Inclusion Criteria

Participants: Adults with neck pain of more than 3 months secondary to mechanical neck disorders, myofascial pain syndrome, cervical spondylosis, cervical spine diseases with radiating pain, and myalgia were included in this study.

Intervention The intervention group received various types of acupuncture (e.g., electroacupuncture, warm acupuncture, abdominal acupuncture, auricular acupuncture, and dry needling) for neck pain. Studies comparing the combination of acupuncture with other intervention measures to those using the same types of interventions alone were included.

Comparison The control group received sham acupuncture, no treatment or active treatments (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, exercise, massage, transcutaneous electrical stimulation, etc.).

Outcomes This study evaluated the sustained efficacy of acupuncture in treating CNP by analyzing pain intensity, neck dysfunction, and quality of life during follow-up over 3 months post-treatment. Pain intensity was assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), and Numerical Rating Scale (NRS). Neck dysfunction was assessed using the Neck Disability Index (NDI) and Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire (NPQ). Quality of life was assessed using the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).

Study Design Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) of acupuncture for CNP were included only if they had a follow-up period of at least 3 months post-treatment.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies involving patients diagnosed with myelopathy were excluded. Whiplash injury was excluded because it may have had a different natural history. Patients with cervical headache/vertigo but without neck pain were omitted from the study. Additionally, studies on acupoint injection, needle-knife therapy, bee venom acupuncture, and studies comparing different acupuncture methods versus Chinese herbal medicine were excluded.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two experienced researchers (JF and HS) independently conducted the study analysis, initially screening titles and abstracts post-deduplication, followed by full-text reviews based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreement was addressed via consensus. Data extraction, performed by the two authors using a predesigned table, was overseen by a senior researcher. The data extracted included the first author, intervention and control measures, sample size, duration of disease, follow-up period, outcome measures, and adverse events.

Assessment of Risk of Bias

Using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool, a revised framework of the Cochrane Collaboration for RCTs, two independent investigators evaluated the bias present in the studies included in the analysis. This tool covers five key domains: the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurements, and selection of reported results. Assessments were classified as "low," "high," or "having some concerns." Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, with a third investigator (ZL) stepping in for consensus if needed.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing Review Manager 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). The mean difference (MD) and 95% CI were calculated for continuous results. Based on the method described by Wan et al. the median and quartile ranges of continuous data were converted into means and standard deviations. The Cochrane QP value and I2 statistics were used to examine the heterogeneity in all meta-analyses. When p value < 0.05 or I2 > 50%, indicating significant heterogeneity, the results were combined using a random-effects model. Otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Egger’s test was used to assess publication bias (only for results containing ten or more studies).

Results

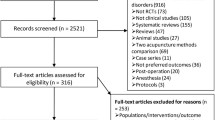

The initial search identified 7639 studies from six databases. After excluding 1553 studies due to duplication, 122 studies were screened based on titles and abstracts. Ultimately, 18 articles met the inclusion criteria. The process of study selection is displayed in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Eighteen studies [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] were included. The sample size, interventions, control, follow-up duration, and outcomes are summarized in Table 1. Interventions included manual acupuncture, dry acupuncture, warm needle moxibustion, and press needles. Seven studies combined acupuncture with manipulation, exercise, or other treatments [25, 26, 29, 32, 36,37,38]. Control group (CG) can be divided into three categories: sham acupuncture (minimal acupuncture at a non-acupoint or unrelated point, or blunt needle without actually piercing the skin), no treatment, and active treatment (such as TENS, traction treatment, self-exercise, and massage). Pain was assessed using the NRS, VAS, and MPQ; neck dysfunction was assessed using the NDI, NPQ, and NPDS; and quality of life was assessed using SF-36.

Risk of Bias Assessment

In our meta-analysis of 18 studies, rigorous randomization resulted in a low risk in this domain. However, 15 studies [21,22,23,24,25,26, 28,29,30, 32,33,34, 36,37,38] lacked detailed descriptions of intervention deviation and adequate blinding, posing a latent risk of bias. Regarding missing outcome data, 11 studies [21, 22, 24, 27,28,29,30,31,32, 34, 36] meticulously reported participant withdrawals and final analysis inclusions, substantiating a low bias risk, while seven studies [23, 25, 26, 33, 35, 37] failed to provide a study flowchart, thereby obscuring the precise number of patients lost to follow-up and thus leading to a high risk of bias. Six studies [22,23,24, 36,37,38] showed unclear selective reporting bias owing to the lack of protocol registration, whereas the remaining 12 [21, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] had a low bias risk in this domain. Overall and individual trial bias risks are both presented in Figs. 2 and 3.

Acupuncture Versus Sham Acupuncture

Pain Intensity

Two studies evaluated the prolonged effects of acupuncture versus sham acupuncture on CNP by assessing the VAS scores at 3, 6, and 12 months post-treatment. Liang et al. [27] reported no statistically significant difference at 3 months (MD: − 0.12; 95% CI − 0.06 to 0.36; p = 0.63) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Similarly, Gattie et al. [31] observed no statistically significant difference at 6 months (MD: 0.01; 95% CI − 1.16 to 1.18; p = 0.99) (Supplementary Fig. 2), a trend that continued at 12 months (MD: − 0.42; 95% CI − 1.55 to 0.71; p = 0.47) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Disability

Three studies compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture in functional improvements using the NDI and NPQ. At 6 months post-treatment, Gattie et al. [31] observed no statistically significant difference in NDI scores (MD: 2.40; 95% CI − 5.46 to 10.26; p = 0.55) (Supplementary Fig. 4). At 12 months, the difference in NDI scores remained insignificant (MD: − 0.11; 95% CI − 7.69 to 7.47; p = 0.98) (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, significant functional benefits were observed at 3 months post-treatment for NPQ. The synthesized data from Liang et al. [27] and Xu et al. [35] showed a notable improvement (MD: − 6.06; 95% CI − 8.20 to − 3.92; p < 0.01; I2 = 45%) (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, this improvement did not reach the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) criterion, defined as a 25% reduction in score from baseline [39].

Quality of Life

The study by Liang et al. [27] found that observations 3 months post-treatment revealed that acupuncture did not exhibit statistically significant improvements over sham acupuncture in both mental component summary (MCS) scores (MD: 5.36; 95% CI: − 1.53 to 12.25; p = 0.13) (Supplementary Fig. 6) and physical component summary (PCS) scores (MD: 1.02; 95% CI: − 6.20 to 8.24; p = 0.78) (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Acupuncture Versus No-Treatment Control

The study by Witt et al. [21] investigated the effect of acupuncture on the quality of life compared with no-treatment using the SF-36. At 3 months post-treatment, acupuncture provided a statistically significant improvement in MCS (MD: 3.20; 95% CI 1.30 to 5.10; p = 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 8), meeting the MCID threshold of 2.5 [40]. However, this improvement diminished at 6 months post-treatment (MD: 0.90; 95% CI 0.36 to 1.44; p = 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 9). The PCS scores initially improved significantly at 3 months post-treatment (MD: 4.60; 95% CI 1.86 to 7.34; p = 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 10), exceeding the MCID of 2.6 [41], but the effect size decreased at 6 months post-treatment (MD: 0.60; 95% CI 0.24 to 0.96; p = 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 11). The study by Witt et al. did not report on pain intensity or function.

Acupuncture Versus Active Control

Pain Intensity

Five studies [22, 23, 25, 30, 34] compared the efficacy of acupuncture with active controls in the management of pain intensity, as measured by the VAS or NRS scoring systems. De et al., Irnich et al., and Valiente et al. compared acupuncture with active treatment in VAS or NRS scores three months after treatment (MD: − 0.17; 95% CI − 0.46 to 12; p = 0.24; I2 = 44%) (Fig. 5), while the studies by Franca et al. and Ilbuldu et al. made a similar comparison at six months (MD: − 1.27; 95% CI − 17.41 to 14.87; p = 0.88; I2 = 55%) (Fig. 6). No statistically significant differences were observed in either time frame.

Disability

Six studies [24, 25, 28, 30, 33, 34] analyzed the long-term efficacy of acupuncture versus active control using the NDI and NPQ to measure disability and functional improvement. At 3 months post-treatment, NDI showed no significant difference (MD: − 0.29; 95% CI − 2.37 to 1.80; p = 0.79; I2 = 23%) (Fig. 7), but at 6 months, a significant difference was observed (MD: − 9.00; 95% CI − 14.06 to − 3.94; p = 0.0005) (Supplementary Fig. 12), meeting the MCID of 3 points [41]. NPQ results indicated significant improvement at 3 months post-treatment (MD: − 6.67; 95% CI − 9.42 to − 3.92; p < 0.01; I2 = 24%) (Fig. 8), persisting at 6 (MD: − 6.33; 95% CI − 9.22 to − 3.44; p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. 13) and 12 months (MD: − 4.75; 95% CI − 7.86 to − 1.64; p = 0.003) (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Acupuncture with Active Control Versus Active Control (add-on)

Pain Intensity

Six studies rigorously evaluated the long-term effectiveness of combining acupuncture with active control interventions versus active control alone for treating CNP. These studies employed various pain assessment tools, including the VAS in five studies [25, 26, 29, 37, 38] to measure pain intensity, the NRS in one study [36], and the MPQ for a comprehensive evaluation of pain in another [38]. At the three-month post-treatment mark, a fixed-effects model analysis of VAS (0–10) and NRS scores (0–100) showed a standardized mean difference (SMD) favoring acupuncture combined with active control over active control alone (SMD: − 0.79; 95% CI − 1.13 to − 0.46; p < 0.01; I2 = 13%) (Fig. 9). At the six-month post-treatment mark, a random-effects model analysis of VAS scores (0–100) indicated that acupuncture with active control maintained a benefit over active control alone (MD: − 18.13; 95% CI − 30.18 to − 6.07; p < 0.01), although with a substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 92%) (Fig. 10). The MPQ reported a mean difference (MD: − 1.03; 95% CI − 2.38 to 0.32; p = 0.13) (Supplementary Fig. 15), meeting the MCID of 1 for MPQ, though it did not reach statistical significance.

Disability

Five studies compared the efficacy of acupuncture combined with active treatment with active treatment alone. Two studies [32, 38 ] reported outcomes at 3 months post-treatment (MD: − 3.83; 95% CI − 9.22 to 1.57; p = 0.16; I2 = 74%) (Fig. 11), and four studies [25, 29, 32, 37] provided data at 6 months (MD: − 9.00; 95% CI − 19.22 to 1.22; p = 0.08; I2 = 98%) (Fig. 12), with no statistical significance.

Safety Assessment

Among the 18 included studies, eight did not report on adverse events, while 10 noted mild adverse events with no severe cases reported. The incidence rate of adverse events in the acupuncture group was 8.5% compared to 3% in the sham acupuncture group, 6.4% in the active treatment group, and 13.8% in the combined acupuncture and active treatment groups. The minor adverse effects associated with acupuncture reported in most studies [25, 29, 31, 32, 34] included minor local bleeding or hematoma after acupuncture and needling pain, with a likelihood of occurrence at 23.7%. Studies by Salter et al. [24] and Stieven et al. [32] indicate a 13.2% chance of transient dizziness, 5.9% of fatigue, and 20.6% of worsening symptoms associated with acupuncture. Liang et al. [27] reported that three patients in the acupuncture group fainted during treatment, and the symptoms were relieved entirely after lying down and drinking hot water.

Discussion

The objective of this review was to evaluate the sustained effects of acupuncture on CNP. CNP characterized by its prolonged course and tendency for recurrence, necessitated extended follow-up periods to adequately assess the sustained effects of acupuncture. The majority of included studies in our analysis opted for follow-up time points of one month (55%), three months (78%), six months (39%), and 12 months (11%) after acupuncture treatment. In evaluating persistent effects, most studies favored follow-up periods exceeding three months [43, 44••]. Consequently, our meta-analysis primarily focused on the outcomes at 3, 6 and 12 months post-treatment.

Compared to sham acupuncture, acupuncture did not demonstrate sustained effects in alleviating pain or improving the quality of life. This finding suggests two possible interpretations: first, acupuncture may not provide a lasting impact in reducing the severity of CNP and enhancing the quality of life; second, sham acupuncture interventions could exhibit therapeutic benefits, potentially due to the placebo effect influenced by patient expectations and beliefs, impacting treatment outcomes [44••]. However, in terms of functional improvements, acupuncture showed certain advantages over sham acupuncture, especially in terms of NPQ scores at the three-month follow-up. This might indicate that the effect of acupuncture on sustained functional recovery surpasses those of psychological factors. Pain and quality of life ratings are susceptible to influences from emotional states, environmental factors, and individual expectations. In contrast, functional status assessments (such as the NPQ scale) may reflect objective physical abilities and the ability to perform daily activities more accurately. Therefore, changes in these domains may not necessarily align perfectly. In the follow-up comparisons between the acupuncture and active control groups, acupuncture did not show significant statistical or clinical differences in pain intensity compared to the active controls. This suggests that its effectiveness in the ongoing control of CNP may be comparable to conventional medication or non-acupuncture physical therapy. However, regarding functional impairment, acupuncture demonstrated a significant improvement at the six-month mark (NDI score), reaching MCID. Furthermore, statistically significant improvements in NPQ scores were observed at 3, 6, and 12 months, indicating that acupuncture may be superior in enhancing functional status and reducing disability than active control. In studies comparing acupuncture combined with active control to active control alone, the combination of acupuncture and active control was more effective in alleviating pain, suggesting that acupuncture as an adjunct therapy may significantly enhance the therapeutic efficacy of conventional treatments. Significant heterogeneity was observed in studies comparing acupuncture with active controls, which may be attributed to variations in the types and intensities of active controls used across studies. Only one study compared acupuncture with a no-treatment group, suggesting that acupuncture might have sustained the effects of acupuncture in improving quality of life.

Despite the mechanisms underlying the efficacy of acupuncture not being fully elucidated, acupuncture stimulation is widely believed to trigger inherent pain control mechanisms in the body, thereby producing analgesic effects [45]. Particularly, neuroplasticity provides a rational explanation for the long-term analgesic effects of acupuncture. For instance, in rat models, low-frequency (2 Hz) electroacupuncture has been shown to induce long-term depression (LTD) in C fibers, leading to sustained pain alleviation [46].

Our findings align with those reported in the review conducted by Yuan et al. [47], which included 17 studies with 1,434 participants. The aggregated evidence from these studies was rated as high-quality. The authors synthesized results from multiple follow-up intervals, revealing that the positive effects of acupuncture on functional impairment were sustained for more than three months. Furthermore, pain reduction was not significantly different compared to sham acupuncture during the follow-up phase. Our investigation extends the follow-up period beyond their scope, appraising the persistent effects at 6 and 12 months post-treatment and evaluating the contribution of acupuncture to enhancing the quality of life.

Acupuncture improves functional status with sustained effects, and as an adjunctive therapy, acupuncture provides sustained relief from pain, Thus, its advantages extend beyond the treatment duration, providing more than just temporary relief of symptoms. This finding is crucial for clinical practice as it addresses a major concern for both patients and healthcare providers: consistent relief can lead to less frequent treatments, thus facilitating more effective CNP management. Another notable aspect of this investigation lies in the outstanding safety profile exhibited by acupuncture, which underscores its potential for wider clinical adoption. Our study has certain limitations. First, there is the predominantly moderate-to-low quality of most of the evidence included. This limitation arises from several factors: a relatively limited scope of literature, with a few outcome indicators reported in only a single source; varied definitions, diagnostic criteria, and treatment methods for CNP across different studies that may have impacted the results; and incomplete assessment of the adverse effects of acupuncture in studies. Furthermore, the articles in our analysis did not report whether patients received any other treatments during the follow-up period, necessitating a cautious interpretation of our results, as any additional treatments could have influenced the outcomes observed post-treatment. We believe that future studies on acupuncture should emphasize its prolonged effects, with follow-ups exceeding three months while ensuring a high-quality design and adequate sample sizes for reliable results.

Conclusion

Acupuncture, as an adjunct therapy, may provide post-treatment pain relief for at least three months among patients with CNP, although its effectiveness is not superior to that of sham acupuncture. The benefits of acupuncture in improving functional impairments extend beyond three months. Despite the necessity for further investigation requiring increased sample sizes, standardized procedures, and meticulous designs, the enduring therapeutic effect of acupuncture and its favorable safety profile, as evidenced by existing research, suggests that it may be a complementary approach for managing CNP.

Data Availability

All data generated in this review are available upon request.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Guzman J, Hurwitz EL, Carroll LJ, Haldeman S, Côté P, Carragee EJ, et al. A new conceptual model of neck pain: linking onset, course, and care: the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 Suppl):S17-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.007.

•• Kim S, Lee SH, Kim MR, Kim EJ, Hwang DS, Lee J, et al. Is cupping therapy effective in patients with neck pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(11):e021070. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021070. This study shows that neck pain has a high rate of disability, which deserves attention.

Viljanen M, Malmivaara A, Uitti J, Rinne M, Palmroos P, Laippala P. Effectiveness of dynamic muscle training, relaxation training, or ordinary activity for chronic neck pain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;327(7413):475. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7413.475.

Bronfort G, Evans R, Nelson B, Aker PD, Goldsmith CH, Vernon H. A randomized clinical trial of exercise and spinal manipulation for patients with chronic neck pain. Spine. 2001;26(7):788–97; discussion 798–799. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200104010-00020.

Alagingi NK. Chronic neck pain and postural rehabilitation: a literature review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2022;32:201–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2022.04.017.

Haldeman S, Carroll L, Cassidy JD, Schubert J, Nygren A. The bone and joint decade 2000–2010 task force on neck pain and its associated disorders: Executive summary. Spine. 2008;33(4 Suppl):S5-7. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181643f40.

• Manchikanti L. Comprehensive review of epidemiology, scope, and impact of spinal pain. Pain Phys. 2009;4;12(4;7):E35–70. https://doi.org/10.36076/ppj.2009/12/E35. It reveals that CNP is prone to recurrent.

Carroll LJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, van der Velde G, Holm LW, Carragee EJ, et al. Course and prognostic factors for neck pain in workers: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000–2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Spine. 2008;33(4 Suppl):S93-100. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816445d4.

Côté P, Wong JJ, Sutton D, Shearer HM, Mior S, Randhawa K, et al. Management of neck pain and associated disorders: a clinical practice guideline from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(7):2000–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4467-7.

Whitfield-Cargile CM, Cohen ND, Chapkin RS, Weeks BR, Davidson LA, Goldsby JS, et al. The microbiota-derived metabolite indole decreases mucosal inflammation and injury in a murine model of NSAID enteropathy. Gut Microbes. 2016;7(3):246–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2016.1156827.

Zhang Y, Leach MJ, Bishop FL, Leung B. A Comparison of the Characteristics of Acupuncture- and Non–Acupuncture-Preferred Consumers: A Secondary Analysis of NHIS 2012 Data. J Altern Complement Med. 2016;22(4):315–22. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2015.0244.

Vickers AJ, Vertosick EA, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE, Sherman KJ, et al. Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Update of an Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2018;19(5):455–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.11.005.

Hershman DL, Unger JM, Greenlee H, Capodice JL, Lew DL, Darke AK, et al. Effect of Acupuncture vs Sham Acupuncture or Waitlist Control on Joint Pain Related to Aromatase Inhibitors Among Women With Early-Stage Breast Cancer. JAMA. 2018;320(2):167–76. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.8907.

Li S, Zhang Z, Jiao Y, Jin G, Wu Y, Xu F, et al. An assessor-blinded, randomized comparative trial of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) combined with cranial electroacupuncture vs. citalopram for depression with chronic pain. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:902450. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.902450.

Fu LM, Li JT, Wu WS. Randomized Controlled Trials of Acupuncture for Neck Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(2):133–45. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2008.0135.

Leaver AM, Refshauge KM, Maher CG, McAuley JH. Conservative interventions provide short-term relief for non-specific neck pain: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2010;56(2):73–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1836-9553(10)70037-0.

MacPherson H, Vertosick EA, Foster NE, Lewith G, Linde K, Sherman KJ, et al. The persistence of the effects of acupuncture after a course of treatment: a meta-analysis of patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2017;158(5):784–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000747.

Oliveira VH, Mendonça KM, Monteiro KS, Silva IS, Santino TA, Nogueira PAM. Physical therapies for postural abnormalities in people with cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;2020(3):CD013018. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013018.pub2.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, for the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339(Jul21 1):b2535–b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1.

Witt CM, Jena S, Brinkhaus B, Liecker B, Wegscheider K, Willich SN. Acupuncture for patients with chronic neck pain. Pain. 2006;125(1):98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.013.

Irnich D, Behrens N, Molzen H, König A, Gleditsch J, Krauss M, Natalis M, Senn E, Beyer A, Schöps P. Randomised trial of acupuncture compared with conventional massage and “sham” laser acupuncture for treatment of chronic neck pain. BMJ. 2001;322(7302):1574–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7302.1574.

Ilbuldu E, Cakmak A, Disci R, Aydin R. Comparison of laser, dry needling, and placebo laser treatments in myofascial pain syndrome. Photomed Laser Surg. 2004;22(4):306–11. https://doi.org/10.1089/pho.2004.22.306.

Salter GC, Roman M, Bland MJ, MacPherson H. Acupuncture for chronic neck pain: a pilot for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7(1):99. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-7-99.

França DLM, Senna-Fernandes V, Cortez CM, Jackson MN, Bernardo-Filho M, Guimarães MAM. Tension neck syndrome treated by acupuncture combined with physiotherapy: A comparative clinical trial (pilot study). Complement Ther Med. 2008;16(5):268–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2008.02.006.

Ma C, Wu S, Li G, Xiao X, Mai M, Yan T. Comparison of Miniscalpel-needle Release, Acupuncture Needling, and Stretching Exercise to Trigger Point in Myofascial Pain Syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(3):251–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b8cdc8.

Liang Z, Zhu X, Yang X, Fu W, Lu A. Assessment of a traditional acupuncture therapy for chronic neck pain: A pilot randomised controlled study. Complement Ther Med. 2011;19:S26-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2010.11.005.

MacPherson H, Tilbrook H, Richmond S, Woodman J, Ballard K, Atkin K, et al. Alexander Technique Lessons or Acupuncture Sessions for Persons With Chronic Neck Pain: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):653–62. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0667.

Cerezo-Téllez E, Torres-Lacomba M, Fuentes-Gallardo I, Perez-Muñoz M, Mayoral-del-Moral O, Lluch-Girbés E, et al. Effectiveness of dry needling for chronic nonspecific neck pain: a randomized, single-blinded, clinical trial. Pain. 2016;157(9):1905–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000591.

De Meulemeester KE, Castelein B, Coppieters I, Barbe T, Cools A, Cagnie B. Comparing Trigger point dry needling and manual pressure technique for the management of myofascial neck/shoulder pain: a randomized clinical trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2017;40(1):11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmpt.2016.10.008.

Gattie E, Cleland JA, Pandya J, Snodgrass S. Dry needling adds no benefit to the treatment of neck pain: a sham-controlled randomized clinical trial with 1-year follow-up. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2021;51(1):37–45. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2021.9864.

Stieven FF, Ferreira GE, Wiebusch M, de Araújo FX, da Rosa LHT, Silva MF. Dry needling combined with guideline-based physical therapy provides no added benefit in the management of chronic neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50(8):447–4. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2020.9389.

Nejati P, Mousavi R, Angoorani H. Acupuncture is as Effective as Exercise for Improvement of Chronic Neck Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Shiraz E-Med J [Internet]. 2020 May 20 [cited 2023 Mar 18];22(3). Available from: https://brieflands.com/articles/semj-97497.html. https://doi.org/10.5812/semj.97497.

Valiente-Castrillo P, Martín-Pintado-Zugasti A, Calvo-Lobo C, Beltran-Alacreu H, Fernández-Carnero J. Effects of pain neuroscience education and dry needling for the management of patients with chronic myofascial neck pain: a randomized clinical trial. Acupunct Med. 2021;39(2):91–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964528420920300.

Xu S, Fu W. Acupoint specificity and effect of acupuncture deqi on cervical pain in cervical spondylosis. China J Tradit Chin Med Pharm. 2014;29(9):3003–7. https://doi.org/CNKI:SUN:BXYY.0.2014-09-089.

Lin X, Luo L, Zhou H, Zhang J, Jiao J. Clinical observation of cervical radiculopathy treated by cervical synchronous traction combined with warm acupuncture and moxibustion. China J Tradit Chin Med Pharm. 2017;32(11):5041–4.

Huang J, Zhang C, Wang J, Chen R, Hu C, Luo L, et al. Effect of intradermal acupuncture (press needle) on pain and motor function in patients with nonspecific neck pain: a randomized controlled study. Chin J Rehabil Theory Pract. 2019;25(4):465–71. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-9771.2019.04.018.

Tang K, Wang T, Xia W, Yang Q, He J, Tong Y. To evaluate the clinical effect of acupuncture on cervical myofascial trigger points in the treatment of cervical radiculopathy by ultrasound elastography. J Chin Physician. 2022;24(7):1087–90. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn431274-20210625-00688.

Sim J, Jordan K, Lewis M, Hill J, Hay EM, Dziedzic K. sensitivity to change and internal consistency of the northwick park neck pain questionnaire and derivation of a minimal clinically important difference. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(9):820–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ajp.0000210937.58439.39.

Strand V, Michalska M, Birchwood C, Pei J, Tuckwell K, Finch R, et al. Impact of tocilizumab administered intravenously or subcutaneously on patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 2018;4(1):e000602. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000602.

Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos GJ, Cramer H. Clinically meaningful differences in pain, disability and quality of life for chronic nonspecific neck pain – A reanalysis of 4 randomized controlled trials of cupping therapy. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21(4):342–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2013.04.005.

•• Bakkum MJ, Tichelaar J, Wellink A, Richir MC, van Agtmael MA. Digital learning to improve safe and effective prescribing: a systematic review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106(6):1236–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1549. This study reveals that the effect of sham acupuncture may be due to the placebo effect.

Kongtharvonskul J, Woratanarat P, McEvoy M, Attia J, Wongsak S, Kawinwonggowit V, et al. Efficacy of glucosamine plus diacerein versus monotherapy of glucosamine: a double-blind, parallel randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18(1):233. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1124-9.

Lv ZT, Shen LL, Zhu B, Zhang ZQ, Ma CY, Huang GF, et al. Effects of intensity of electroacupuncture on chronic pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1899-6.

Coutaux A. Non-pharmacological treatments for pain relief: TENS and acupuncture. Joint Bone Spine. 2017;84(6):657–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.02.005.

Xing GG, Liu FY, Qu XX, Han JS, Wan Y. Long-term synaptic plasticity in the spinal dorsal horn and its modulation by electroacupuncture in rats with neuropathic pain. Exp Neurol. 2007;208(2):323–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.09.004.

Yuan QL, Guo TM, Liu L, Sun F, Zhang YG. Traditional Chinese medicine for neck pain and low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Baak JPA, editor. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0117146. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117146.

Funding

This study was supported by funding from the High Level Chinese Medical Hospital Promotion Project, with grant number No. HLCMHPP2023089.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JF and HS made equal contributions to this study and are co-first authors. They were responsible for designing the study, analyzing the data, and drafting the manuscript. WW and HC conducted the literature search, selected trials, and also contributed to drafting the manuscript. MY, YH, and SG were involved in data extraction and analysis. YY and LZ conducted initial revisions of the manuscript and assessed the risk of bias in the included trials. ZL supervised the project and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, J., Shi, H., Wang, W. et al. Durable Effect of Acupuncture for Chronic Neck Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr Pain Headache Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-024-01267-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-024-01267-x