Abstract

Purpose of Review

There is a growing evidence base describing population health approaches to improve blood pressure control. We reviewed emerging trends in hypertension population health management and present implementation considerations from an intervention called Team-supported, Electronic health record-leveraged, Active Management (TEAM). By doing so, we highlight the role of population health managers, practitioners who use population level data and to proactively engage at-risk patients, in improving blood pressure control.

Recent Findings

Within a population health paradigm, we discuss telehealth-delivered approaches to equitably improve hypertension care delivery. Additionally, we explore implementation considerations and complementary features of team-based, telehealth-delivered, population health management. By leveraging the unique role and expertise of a population health manager as core member of team-based telehealth, health systems can implement a cost-effective and scalable intervention that addresses multi-level barriers to hypertension care delivery.

Summary

We describe the literature of telehealth-based population health management for patients with hypertension. Using the TEAM intervention as a case study, we then present implementation considerations and intervention adaptations to integrate a population health manager within the health care team and effectively manage hypertension for a defined patient population. We emphasize practical considerations to inform implementation, scaling, and sustainability. We highlight future research directions to advance the field and support translational efforts in diverse clinical and community contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hypertension (HTN) affects approximately 116 million adults in the USA [1]. It is one of the most prevalent contributors to cardiovascular disease, resulting in approximately 659,000 deaths in the USA each year [2, 3]. While HTN alone is associated with cardiovascular disease and “all cause” mortality, its high co-occurrence with obesity, dyslipidemia, and diabetes makes HTN a persistent obstacle towards improved outcomes and equity and a significant driver of costs. When adjusting for age, the burden of HTN and related chronic conditions falls disproportionately on underserved communities [4]. As such, improving HTN outcomes among underserved communities is a priority area of focus for population health management efforts. Population health management is defined by its proactive focus on the health needs of a defined population or community, in contrast to exclusively reacting to individual level patient medical needs when they arise [5, 6]. Within a population health paradigm, HTN management leverages technologies to identify and engage at-risk populations, thereby increasing reach and the potential for impact particularly among underserved communities.

There are multiple evidence-based strategies to manage HTN, including lifestyle modifications and medications. When HTN control is achieved, stroke is reduced 35–40%, myocardial infarction 20–25%, and heart failure over 50% [7, 8]. However, uptake of lifestyle modifications and adherence to medications is suboptimal, so HTN control is often not achieved. In an analysis of 2015–2018 data, only 26.1% of adults with diagnosed HTN and prescribed medication achieved HTN control [9]. Patients’ long-term non-adherence rate to provider’s pharmacotherapy recommendations range from 50–70% [10]. Patient-level barriers associated with this lack of treatment and self-management include suboptimal adherence to medication or behavioral interventions and lack of knowledge and self-efficacy specific to managing HTN [11, 12]. Provider-level barriers to evidence-based HTN management include insufficient time to spend with patients and clinical inertia which can result in failure to intensify treatments [13,14,15]. In fact, two-thirds of all suboptimal HTN treatment in the USA originates from inadequate provider treatment [16]. Provider challenges related to the complexity of polypharmacy is associated with suboptimal treatment adherence, which in turn leads to poor HTN control [17]. System level barriers such as a lack of care coordination, decision support, and access to BP monitoring/follow-up exacerbate existing challenges to HTN treatment [18]. The cumulative effect of barriers at the patient, provider, and system level is suboptimal HTN treatment. To be effective, population health management initiatives must recognize and work within and across each of these levels to achieve optimal blood pressure control targets.

In practice, population health management often refers to a range of health care services and analytics that support a coordinated and proactive approach to support improved outcomes for a community. In other words, the goal of population health management is to improve the health and well-being of a specific group of people or community [19••]. To this end, population health management uses multilevel approaches that require careful attention to the broader context of patient situations (e.g., low-income communities, limited transportation options, nutritious food availability, beliefs and norms, rurality) to better understand context-specific drivers of outcomes. By taking these multilevel factors into account, models of care can be more tailored and responsive.

We summarize emerging evidence to support HTN population health management as an effective responsive to the multi-level drivers of inequitable outcomes. First, we highlight several distinct yet complementary components of emerging best practices for designing HTN population health management initiatives: (1) population health management and the role of a population health manager; (2) team-based care; (3) telehealth modalities; and (4) the electronic health record (EHR). Second, we describe how the chronic care model can be used to guide the design of multi-level interventions. Third, we use the TEAM intervention as a case study to present implementation considerations and intervention adaptations to effectively manage HTN for a defined patient population. In describing the implementation processes, we emphasize practical considerations associated with intervention design, adaptation, scaling, and sustainability in real-world contexts. Finally, we provide perspective on future research directions and opportunities to support the translation of TEAM and HTN population health approaches like it into practice.

Components of Approaches to HTN Population Health Management

-

1.

Population Health Management and the Role of a Population Health Manager

Population Health Management

Serxner et al. described the core components of population health management including attention to the full continuum of care, data sharing, and multidisciplinary care coordination [20]. Similarly, Matthews et al. focused on the shift of the role of health care systems from sporadic and episodic encounters to serve individuals in need of immediate care towards accountability for the health and well-being of an entire patient population [21]. When treatment interventions are organized and delivered through a population health management paradigm, interventions have the potential to lessen health disparities by proactively focusing on both unmet clinical and health-related social needs. Examples of population health management interventions to promote health equity include implementation of a system-wide screening intervention to decrease disparities in colorectal cancer screening rates [22], a care-management intervention bridging the transition from in-patient to out-patient mental health care to reduce readmissions of at-risk patients [23], and community partnerships and coordination to promote treatment adherence [24, 25•]. Additionally, interventions based on population health management are effective in achieving BP control for patients with uncontrolled HTN. For example, in a propensity score-matched cohort study of patients that received multi-disciplinary team case management to address HTN disparities in Baltimore, patients that completed all three sessions (39%) experienced reductions in systolic (9 mmHg) and diastolic blood pressure (4 mmHg) greater than matched controls with no disparities in these reductions among White and Black patients [26•].

By taking a population health approach, we consider how inequities and social determinants of health shape why certain populations have differential health outcomes [27]. As population health management continues to gain prominence in the context of value-based care [28], it is critical to design HTN interventions and support translational efforts to ensure use in clinical practice. To translate evidence-based population health management interventions into practice, there are considerations that may impact the roles, responsibilities, composition, and staffing priorities of the care team and health system.

Population Health Manager

One emerging role that is central to population health management is that of the population health manager. A population health manager is a member of the health care team who uses population-level health data to identify unmet needs, intervene, and improve inequities and clinical outcomes among a defined community, usually within a shared geographic area. When embedded within the care team, the population health manager provides culturally appropriate counseling and gives support to patients related to their health self-management, navigating community resources or social services, and promoting treatment adherence [29,30,31]. Furthermore, a population health manager considers patient-level factors (e.g., self-efficacy, medical needs, social needs), clinic-level factors (e.g., specialty providers, community-based care, wrap-around service availability), and system-level factors (e.g., physical environment, eligibility and access to health and social services, and locally available resources), when developing health strategies [32, 33]. Many times, nurses fill the role of population health managers as the role, purpose, and function of the population health manager complement the nurse’s training and approach to health and wellness.

Within the context of HTN, a population health manager would consider the patients’ cultural preferences and environment to tailor strategies for promoting self-management and medication and treatment adherence for HTN risk reduction. The reorientation of the health care workforce towards population health management, including the adoption of population health managers into care teams, represents an important opportunity to improve population health HTN outcomes and complement providers’ clinical management activities.

-

2.

Team-Based Care

Team-based care is an essential component of a population health approach for HTN management. Team-based care models include personnel from both clinical specialties (e.g., social work, medicine, nursing) and non-clinical specialties (e.g., community health worker, data science, informatics) and are an evidence-based approach to improve health outcomes and quality of care, especially for those with chronic conditions. Effective team-based care models focus on disease management, provider coordination, performance measurement, the process of care delivery, and engaging the patient in decision making to promote self-management [34]. A team-based approach to HTN care is ideal but can be challenging in practice; for example, a patient’s primary care provider may not be able to easily view records and information generated by other providers. As a result, medication non-adherence or non-optimal prescribing patterns can result from lack of continuity of care due to barriers to information sharing [15, 35]. A change in health behavior due to team-based care is particularly relevant to a condition such as HTN in which sustained treatment adherence and self-management are critical.

HTN team-based care interventions are associated with improved BP control and lower systolic and diastolic BP (especially when pharmacists and nurses are involved) and predict effectiveness of drugs [36••, 37•]. Specifically, a 2009 meta-analysis by Carter at el. found that HTN interventions that emphasized integrating complementary roles and clinical specialties had large effect sizes on systolic blood pressure (SBP). For example, effective team-based care strategies included pharmacist treatment recommendations (− 9.30 mm Hg), nurse led interventions (− 4.80 mm Hg), and use of a treatment algorithm enabled through clinical informaticist support (− 4.00 mm Hg) [36••]. Team-based care not only has the potential to improve HTN outcomes, but also represents an extremely cost-effective approach to HTN management [38•, 39]. A 2015 economic systematic review of team-based care interventions to control blood pressure found that they almost all were cost-effective at the most conservative threshold of $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) [40]. In addition, studies demonstrate that team-based care can increase patient satisfaction [40]. There is also an emerging evidence base that team-based care may be a mechanism for improving health equity. An analysis of 12 systematic reviews of the literature describing promising patterns and designs of interventions to reduce health disparities identified multidisciplinary team-based care interventions that were culturally tailored as a promising strategy [41].

-

3.

Leveraging Telehealth Modalities

Effective population health management should consider strategic integration of existing technologies and digital platforms including telehealth to engage patients [42•]. Telehealth is when a healthcare system exchanges medical information through electronic communication platforms to address a patient’s health [43, 44]. Telehealth enabled communication can occur between clinicians, clinician and patient, and patient and mobile health technology to perform a variety of services including counseling, medication management, education, and monitoring. Telehealth occurs via two-way synchronous video or audio-only (e.g., by telephone) communication to complement or substitute in-person encounters as an efficient and convenient, accessible mechanism for chronic care delivery. Notably, the COVID-19 global pandemic and associated changes to telehealth reimbursement and regulatory policies have accelerated adoption of telehealth infrastructure across medical specialty service lines, a trend that continued after in-person visit volume returned to pre-pandemic levels [45].

There is an emerging evidence base describing effective telehealth approaches for patients with HTN and related chronic conditions. Specifically, telehealth technologies represent an important opportunity to improve HTN population health by addressing the multi-level drivers of blood pressure control. For example, in a 4-year randomized control trial, a nurse-led behavioral intervention administered via telephonic encounters showed an increase in HTN control by 13% when compared to usual care [46]. Another recent study showed that when used in conjunction with electronic health databases, telehealth interventions can improve quality of life, disease stability, and treatment compliance in elderly patients with co-morbid diseases [47]. Telehealth interventions are a promising mechanism for modifying patient non-adherence behaviors [48, 49]. A systematic review of telehealth application included a broad range of clinical applications and showed that telehealth interventions as adjuncts to routine care produces positive outcomes and that the most pronounced benefits were for chronic conditions like HTN [45]. For example, telephone-based interventions improve treatment adherence and blood-pressure control in individuals with HTN [50•]. Telehealth interventions also show promise for promoting health equity. When compared to usual care, nurse implemented telemedicine that combined behavioral and medical interventions improved mean systolic blood pressure, especially in African Americans [51]. Telephone-administered behavioral interventions have also shown success in HTN control and promise in Medicaid patients [52, 53•, 54, 55, 56•, 57, 58]. For example, in one 2011 study, implementing a telehealth HTN behavioral intervention resulted in treatment adherence increase from 55 to 77% in Medicaid patients [53•]. One study implementing a telephone administered behavioral intervention at three primary care clinics versus nine usual care sites showed success in larger-scale implementation; however, there is still a gap between discovery and delivery. Despite evidence that these interventions can be effective in controlled research conditions, there is a need to better understand (i) what is necessary to introduce and sustain a novel intervention into routine clinical care and (ii) what aspects of the intervention are critical to preserve to produce the same results in “real-world” clinical and community settings [52]. As telehealth becomes a more common treatment intervention, health system-wide data for tailored scaling across a defined population is a critical need and implementation consideration [59].

-

4.

The Role of the EHR

Effective and efficient HTN care models often feature the use of EHR technologies to identify patients, coordinate activities, and engage through behavioral interventions in a timely manner. In fact, emerging technologies related to telemonitoring’s capture and integration within the EHR may represent an important opportunity for the field to augment and synergize with team-based care [60••]. Thus, there is an important role for system-level investments in clinical information systems and technology infrastructure to facilitate HTN team-based care and population health management.

Population health management interventions that leverage the EHR can improve population health by identifying high risk patients. EHRs include physical assessments and medical histories of individual patients to assess cardiovascular risk and rising risk [61]. EHRs can be used to evaluate interventions and predict risk, especially when integrated with other sources including data on social determinants [56•, 62]. For example, data obtained from EHRs can be used to predict development of HTN and coronary heart disease, or to track associations between hospitalizations and patient characteristics related to heart-failure [63,64,65]. Additionally, EHRs can be used to assess health disparities [66] and inform the development of interventions to improve both health equity and outcomes.

The use of EHRs to inform interventions has implications for the design of population health surveillance efforts. New York City created a system to track HTN prevalence using aggregate EHR data from a network of outpatient practices. This example represents an opportunity to leverage EHR infrastructures at the population level and use the EHR to go beyond syndromic surveillance and quality improvement at the individual and practice levels [67, 68]. Similarly, when a health maintenance organization system implemented a population-based HTN management program, they were able to achieve above 80% blood pressure control across the population represented in the hypertension registry [69•]. A key facet of the program was a comprehensive, EHR-based, HTN registry to enable customizable queries that informed prioritization of patient subgroups (e.g., individuals with poorly controlled hypertension, underserved communities) that would benefit from treatment intensification. This risk stratification is consistent with a review of HTN interventions that found the most effective approaches included population (e.g., clinic or panel-level review) rather than an exclusive focus on patient-level intervention [70]. Using EHRs to enable a HTN population program deployed in concert with a team-based telehealth approach is synergistic and facilitates response to patient, provider, and system level barriers to HTN management.

Applying the Chronic Care Model to Design HTN Population Health Management Approaches

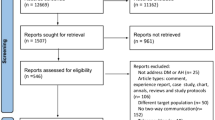

A HTN intervention within a population health paradigm should include an inclusive approach which incorporates chronic care model (CCM) concepts, including self-management support, care coordination, enhanced clinical information systems (e.g., clinical registries and telehealth), and decision support [71]. Therefore, data-driven (e.g., EHR), team-coordinated, telehealth technologies and intervention strategies facilitated by a population health manager represent complementary approaches to advance HTN population health management. We conducted a narrative review to describe the evidence base of these synergistic strategies that fit seamlessly within a population health management care paradigm. Table 1 summarizes particularly relevant studies the describe the role of a population health manager and the use of team-based care, the EHR, and telehealth to better manage HTN.

Based on the range of system-level factors that impact HTN outcomes and access to care, telehealth and virtual care address system level barriers to care by facilitating improved access. However, system level factors and social determinants of health present unique challenges and opportunities for uptake. For example, there are concerns that telehealth technologies may impact health equity if uptake, particularly for synchronous audio–video technologies, is greater among wealthier, white, and younger patients [72, 73]. Variation of telehealth use is due to multi-factorial drivers including differences in social determinants (e.g., access to a reliable internet connection, patient and provider preferences, technological literacy, condition complexity, and medical visit type) [74,75,76]. However, evidence from the VA, which serves a significant rural patient population, suggests that telephonic telehealth may be an effective mechanism for improving access to care for more remote, underserved communities [77, 78]. While effective best practices for telehealth continue to emerge across the care continuum, there is a need to advance integration of telehealth approaches within a population health management paradigm (i.e., proactive, focused on a population and equity), requiring complementary team-based models of care and EHR-enabled identification and coordination. To better illustrate the intersection of telehealth and population health management, we present an evidence-based intervention called TEAM [79••].

Case Study: Team-Supported, EHR-Leveraged, Active Management (TEAM) Intervention

As the largest integrated health care system in the USA, the Veterans Affairs’ Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has a unique opportunity to manage HTN using a population health approach and presents an integrated care environment which allows for a successful intervention because of advancements in care coordination and management [71]. A population health approach in the context of the VHA includes leveraging a team of specialists drawing from the integrated system to work together. Care coordination is an especially critical consideration for rural communities that the VHA disproportionately serves, who face challenges associated with higher rates of HTN and inadequate local resources [81]. To address this challenge and integrate the aforementioned components of effective HTN population health management, we developed Team-supported, EHR-leveraged, Active Management (TEAM) based on stakeholder feedback using existing health care system employees, resources, and technological infrastructure.

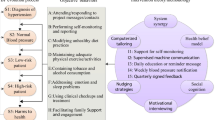

TEAM leverages capabilities of an integrated health care system consistent with best practices for improving HTN population health outcomes. TEAM includes a targeted approach to a defined patient population using the electronic health record, a team-based approach featuring a nurse population health manager and leveraging existing telehealth infrastructure. TEAM consists of five core components: (1) identification of patients with uncontrolled HTN for enrollment according to criteria using an EHR-based query; (2) the patients received a CVD risk letter; (3) the population health manager created and entered a detailed care plan based on patient needs; (4) the primary care team ordered appropriate treatment; and (5) the population health manager reported patient progress [79••]. These complementary core components support Veterans in achieving optimal blood pressure control (Fig. 1). The pilot study of TEAM intervention demonstrated improved patient and system level outcomes, including improvements in HTN control [79••]. On the patient level, at 45 days following the TEAM intervention, 40% of patients had blood pressure measurements < 140/90 mm Hg. Compared with baseline (151/95 mm Hg), there was an average reduction of 11 mmHg and 5 mmHg, on systolic and diastolic blood pressure, respectively. This BP improvement was accomplished through improved patient engagement to adopt self-management behaviors and engage in productive interactions with their health care team. After the intervention, 61% of patients scheduled appointments, 83% attended scheduled appointments, and 62% contacted a healthcare provider either check their BP, change medications, or get a referral for a health service [79••]. The promising findings of the TEAM intervention are likely due to the complementary components based on emerging best practices in the HTN population health management literature; however, the integration of TEAM into real-world practices required modifications and adaptations to ensure fit.

TEAM Adaptations

Few research-developed interventions are adopted into real-world practice settings [82]. When they are, they are regularly modified or adapted to meet the needs of the target population or to match the clinical context. Often this process of modification is driven by constraints or contextual factors (e.g., staffing, cultural considerations, resource availability) and is done without a strategic or purposeful approach to ensure fidelity to the intervention’s original design. To support translational efforts, especially for multi-level interventions, it is critical to carefully and intentionally adapt interventions to match their intended context without compromising the essential elements that make it effective. Herein we describe TEAM intervention adaptation to better integrate in real-world clinical environments within diverse VA clinics. We used the Stirman et al.’s Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications-Expanded (FRAME) to analyze and organize TEAM intervention refinements, additions, and modifications [83, 84]. By doing so, both practitioners and researchers can assess the rationale, timing, relationship to fidelity, and the impact of the modifications to ensure the intervention will retain its effectiveness.

FRAME classifies adaptations across different categories to inform reporting. These include (1) when and how the modification(s) were made, (2) whether it was planned/proactive (i.e., an adaptation) or unplanned/reactive, (3) the stakeholder that determined that the modification should be made, (4) what is modified, (5) the level of delivery that the modification is made (e.g., individual, cohort, practitioner, clinic, network, or system/community), (6) the nature of content-level modifications (e.g., substitution, addition, integrating other evidence based components), (7) the extent to which fidelity is preserved, and (8) the modification rationale (e.g., the intent or goal of the modification or the contextual implementation factors that the modification was made in response to).

We documented the adaptations and changes to the TEAM protocol by engaging with front-line stakeholders, investigators, and research staff. Once feedback had been collated, we organized and reported adaptations to intervention components consistent with FRAME. Adaptations were developed proactively and iteratively at a single site during a pilot phase to identify barriers to implementation and implementation strategies. We focused on adaptations across four core elements of the TEAM intervention: (i) identification and screening of eligible patients; (ii) recruitment and outreach; (iii) patient engagement and activation; (iv): EHR-enabled documentation and team-based care planning. The evaluation of modifications to improve fit with local practice patterns and capabilities can inform the design of implementation strategies and provide practical considerations for practitioners for integrating TEAM and evidence-based HTN population health management approaches like it (see Table 2). For example, we found that adaptations ranged from minor “tweaks” to facilitate adoption (e.g., minor changes to inclusion criteria to reach more patients or utilizing locally available technologies to promote communication and care planning) to more significant alterations of the intervention (e.g., removing medication adjustments as a component of the intervention). These data on implementation and adaptations were used to identify relevant and agreed upon implementation strategies to overcome anticipated implementation barriers as we implemented TEAM at additional subsequent VHA sites. By providing guidance and technical assistance on permissible adaptations that can be made without compromising intervention fidelity, translational efforts to integrate TEAM into real-world clinical settings can be better supported.

Implementation Considerations and Lessons Learned

Adaptations are a key concept in implementation to improve intervention fit or effectiveness in a specific context. The aforementioned modifications rarely exist within a vacuum and are often made in response to implementation factors. To highlight implementation factors associated with TEAM, we assessed implementation context based on the Consolidated Framework For Implementation Research (CFIR), a framework centered on (1) intervention characteristics, or attributes of TEAM that impact implementation success; (2) outer setting, or economic and social factors within the community and health system that affect implementation; (3) inner setting, or contextual factors within the health system and clinics that influence implementation; (4) individual characteristics of the individuals that use TEAM; and (5) implementation processes, or actions taken by individuals to implement [85, 86]. The experience using a population health manager within a multi-level HTN population health management intervention requires attention to the implementation factors across domains captured by CFIR. In Table 3, we summarize these lessons learned and map them to CFIR domains and constructs to illustrate the complex interplay between the intervention, context, and the dynamic processes, systems, and agents that can drive or inhibit implementation, for example, defining roles and performance metrics and establishing communication channels and protocols for team-based care.

Conclusion

HTN population health management is an important frontier for the field that requires adapting best practices within a population health paradigm consistent with the CCM. We describe relevant literature and discuss the resulting implications for staffing, organization of care, integration of technologies and analytics, and implementation by exploring promising, evidence-based components including leveraging the EHR, team-based care, telehealth, and novel care team composition (e.g., the role of a population health manager). These strategies and components are successful because they advance HTN care in a CCM consistent and organized way within a population health paradigm by being responsive to the multi-level drivers of poor HTN adherence and outcomes.

We use the TEAM intervention as an exemplar that has demonstrated improved patient and system level outcomes, including improvements in HTN control [79••]. Specifically, TEAM improved engagement and management in patients with high BP and led to improved clinical outcomes [79••]. We also explore the challenges to translating intervention components developed in a research context into routine care and the need for strategic and proactive adaptation. In doing so, we highlight the complex interplay and practical considerations of modifying an intervention to facilitate adoption balanced with the importance of maintaining fidelity to evidence-based components. These adaptations range from “tweaks” to substantive modifications and should be monitored carefully to ensure that effectiveness is not diminished. The experience with TEAM in the VA highlights the promise of translational efforts but should be interpreted with caution. As TEAM and interventions like it are moved outside of a VA institutional environment into community and other clinical contexts, further adaptation will be needed in response to dynamic factors including patient characteristics, data availability, and existing infrastructure.

Availability of Data and Material

Upon request from Dr. Bosworth, the project lead of TEAM.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Facts about hypertension. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm. Accessed 7 April 2021.

Kannel WB. Blood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor. JAMA. 1996;275(20):1571. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1996.03530440051036.

Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143:e254–743.

Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple chronic conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand. 2017;10.

Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Deswal A, Dunbar SB, Francis GS, Horwich T, et al. Contributory risk and management of comorbidities of hypertension, obesity, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and metabolic syndrome in chronic heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134(23):535–78. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000450.

Long AN, Dagogo-Jack S. The comorbidities of diabetes and hypertension: mechanisms and approach to target organ protection. J Clin Hypertens. 2013;13(4):244–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/2Fj.1751-7176.2011.00434.x

Yoon PW, Gillespie CD, George MG, Wall HK, Centers for Disease C. Prevention Control of hypertension among adults--National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2005–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61 Suppl:19–25. PMID: 22695459

Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman N. Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood-pressure-lowering drugs: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials. Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. Lancet. 2000;356(9246):1955–1964.

Ritchey MD, Gillespie C, Wozniak G, et al. Potential need for expanded pharmacologic treatment and lifestyle modification services under the 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline. The J Clin Hyper. 2018;20(10):1377–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13364.

Adherence to long-term therapies. evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Org 2003.

Bosworth HB, Oddone EZ, Weinberger M. Patient treatment adherence: concepts, interventions, and measurement. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Asso 2006.

Hong TB, Oddone EZ, Dudley TK, Bosworth HB. Medication barriers and anti-hypertensive medication adherence: the moderating role of locus of control. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(1):20–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786430500228580.

Okonofua EC, Simpson KN, Jesri A, Rehman SU, Durkalski VL, Egan BM. Therapeutic inertia is an impediment to achieving the Healthy People 2010 blood pressure control goals. Hypertension. 2006;47(3):345–51. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.0000200702.76436.4b.

Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Karter AJ, et al. Why don’t diabetes patients achieve recommended risk factor targets? Poor adherence versus lack of treatment intensification. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):588–594. https://doi.org/10.1007/2Fs11606-008-0554-8

Ho PM, Bryson CL, Rumsfeld JS. Medication adherence: its importance in cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2009;119(23):3028–35. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.108.768986.

Wang TJ, Vasan RS. Epidemiology of uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. Circulation. 2005;112(11):1651–62. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.104.490599.

Egan BM, Zhao Y, Li J, et al. Prevalence of optimal treatment regimens in patients with apparent treatment-resistant hypertension based on office blood pressure in a community-based practice network. Hypertension. 2013;62(4):691–7. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.113.01448.

Steinbrook R. Health care and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1057–60. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp0900665.

•• Steenkamer BM, Drewes HW, Heijink R, Baan CA, Struijs JN. Defining population health management: a scoping review of the literature. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20(1):74–85. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2015.0149. A comprehensive definition of population health management.

Serxner S, Noeldner SP, Gold D. Best practices for an integrated population health management (PHM) program. Am J Health Promot 2006;20(5 suppl):1–10, iii. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-20.5.tahp-1

Matthews MB, Hodach R. Automation is key to managing a population’s health. Healthc Financ Manage. 2012;66(4):74–8 (PMID: 22523891).

Berkowitz SA, Percac-Lima S, Ashburner JM, Chang Y, Zai AH, He W, et al. Building equity improvement into quality improvement: reducing socioeconomic disparities in colorectal cancer screening as part of population health management. J Gen Inter Med. 2015;30:942–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3227-4.

Hutchison SL, Flanagan JV, Karpov I, et al. Care management intervention to decrease psychiatric and substance use disorder readmissions in Medicaid-enrolled adults. J Behav Health Serv Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-018-9614-y

Jones LK, Greskovic G, Grassi DM, et al. Medication therapy disease management: Geisinger’s approach to population health management. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:1422–35. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp161061.

• Halladay JR, Donahue KE, Hinderliter AL, et al. The heart healthy lenoir project-an intervention to reduce disparities in hypertension control: study protocol. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-441. An exemplar population health management intervention to improve hypertension outcomes for an underserved population.

• Hussain T, Franz W, Brown E, et al. The role of care management as a population health intervention to address disparities and control hypertension: a quasi-experimental observational study. Ethn Dis. 2016;26(3):285–294. Published 2016 Jul 21. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.26.3.285. An exemplar population health management intervention to improve hypertension outcomes for an underserved population.

Young TK. Population health: concepts and methods. 2nd Ed. Oxford University Press; 2004.

Felt-Lisk S, Higgins T. Exploring the promise of population health management programs to improve health. Mathematica. 2001.

Brownstein JN, Chowdhury FM, Norris SL, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of people with hypertension. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):435–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.011.

Norris SL, Chowdhury FM, Van Le K, et al. Effectiveness of community health workers in the care of persons with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23(5):544–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01845.x.

Dolor RJ, Yancy WS Jr, Owen WF, et al. Hypertension Improvement Project (HIP): study protocol and implementation challenges. Trials. 2009;10:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-10-13.

Radzyminski S. The concept of population health within the nursing profession. J Prof Nurs. 2007;23(1):37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.10.004.

Moore M, Peterson L, Coffman M, Jabbarpour Y. Care coordination and population management services are more prevalent in large practices and patient-centered medical homes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(6):652–3. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2016.06.160180.

Goldberd DG, Beeson T, Kuzel AJ, Love LE, Carver MC. Team-based care: a critical element of primary care practice transformation. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(3). https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2012.0059

Flocke SA, Strange KC, Zyzanski SJ. The impact of insurance type and forced discontinuity on the delivery of primary care. J Fam Pract. 1997;45(2):129–35 (PMID: 9267371).

•• Carter BL, Rogers M, Daly J, Zheng S, James PA. The potency of team-based care interventions for hypertension: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19). https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.316. A ground breaking systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate team based care interventions’ impact on hypertension outcomes.

• Proia KK, Thota AB, Njie GJ, Finnie RKC, Hopkins DP, Mukhtar Q, et al. Preventive services task force, community. team-based care and improved blood pressure control: a community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(1):86–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.03.004 . An exemplar population health management intervention that features team based care to improve hypertension outcomes.

• Jacob V, Chattopadhyay SK, Thota AB, Proia KK, Njie G, Hopkins DP, et al. Preventive Services Task Force, Community. Economics of team-based care in controlling blood pressure: a community guide systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(5):772–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.003 . A systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis of team based care interventions to improve hypertension outcomes.

Wohler DM, Liaw W. Team-based primary care: opportunities and challenges. Starfield Summit; 2016.

Wen J, Schulman KA. Can team-based care improve patient satisfaction? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7): e100603. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100603.

Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):992–1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9.

• Milani RV, Lavie CJ, Bober RM, Milani AR, Ventura HO. Improving hypertension control and patient engagement using Digital Tools. Am J Med. 2017;130(1):14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.07.029. An exemplar population health management intervention that features digital medicine to improve hypertension outcomes.

Bingham JM, Black M, Anderson EJ, et al. Impact of telehealth interventions on medication adherence for patients with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and/or dyslipidemia: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2021;55(5):637–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028020950726.

Tuckson RV, Edmunds M, Hodgkins ML. Telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1585–92. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsr1503323.

Drake C, Lian T, Cameron B, Medynskaya K, Bosworth HB, Shah K. Understanding telemedicine’s “New normal”: variations in telemedicine use by Specialty Line and patient demographics. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0041.

Bosworth H, Olsen MK, Dudley T, Orr M, Goldstein MK, Datta SK, et al. The Veterans’ Study to Improve The Control of Hypertension (V-STITCH): a patient and provider intervention to improve blood pressure control. In: 25th HSR&D National Meeting. Washington: DC; 2007. p. 15.

Noel HC, Vogel DC, Erdos JJ, Cornwall D, Levin F. Home telehealth reduces healthcare costs. Telemed J E Health. 2005;10(2)

Totten AM, Womack DM, Eden KB, et al. Telehealth: mapping the evidence for patient outcomes from systematic reviews. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), Rockville (MD); 2016. PMID: 27536752

Totten AM, Womack DM, Eden KB, et al. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

• Friedman RH, Kazis LE, Smith MB, Stollerman J, Torgerson J, Carey K. A telecommunications system for monitoring and counseling patients with hypertension. Impact on medication adherence and blood pressure control. Am J Hypertens. 1996;9(4 Pt 1):285–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-7061(95)00353-3 . An exemplar medication adherence intervention that features telehealth to improve hypertension outcomes.

Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, McCant F, Harrelson M, Gentry P, Rose C, et al. Hypertension Intervention Nurse Telemedicine Study (HINTS): testing a multifactorial tailored behavioral/educational and a medication management intervention for blood pressure control. Am Heart J. 2007;153(6):918–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.004.

Bosworth HB, Almirall D, Weiner BJ, Maciejewski M, Kaufman MA, Powers BJ, et al. The implementation of a translational study involving a primary care based behavioral program to improve blood pressure control: The HTN-IMPROVE study protocol (01295). Implement Sci. 2010;16(5):54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-54.

• Bosworth HB, DuBard CA, Ruppenkamp J, Trygstad T, Hewson DL, Jackson GL. Evaluation of a self-management implementation intervention to improve hypertension control among patients in Medicaid. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1(1):191–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-010-0007-x. An exemplar population health management intervention that features telehealth outreach across a statewide Medicaid population to improve hypertension outcomes.

Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Gentry P, et al. Nurse administered telephone intervention for Blood Pressure Control: a patient-tailored multifactorial intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(1):5–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2004.03.011.

Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Neary A, et al. Take control of your blood pressure (TCYB) study: a multifactorial tailored behavioral and educational intervention for achieving blood pressure control. Patient Educ and Couns. 2008;70(3):338–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.014.

• Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Grubber JM, et al. Two self-management interventions to improve hypertension control. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):687. https://doi.org/10.7326/0000605-200911170-00148. An exemplar population health management intervention that leveraged telehealth and remote monitoring to improve hypertension outcomes.

Bosworth HB, Powers BJ, Olsen MK, et al. Home blood pressure management and improved blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1173. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.276.

Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Dudley T, et al. Patient education and provider decision support to control blood pressure in primary care: a cluster randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2009;157(3):450–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.003.

Abbott PA, Liu Y. A scoping review of telehealth. Yearb Med Inform. 2013;8:51–8 (PMID: 23974548).

•• Derington CG, King JB, Bryant KB, et al. Cost-effectiveness and challenges of implementing intensive blood pressure goals and team-based care. Current Hypertension Reports. 2019;21(12). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-019-0996-x . An overview of the cost-effectiveness and implementation of team-based care models to improve hypertension outcomes.

Häyrinen K, Saranto K, Nykänen P. Definition, structure, content, use and impacts of electronic health records: a review of the research literature. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77(5):291–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.09.001.

Drake C, Lian T, Trogdon JG, et al. Evaluating the association of social needs assessment data with Cardiometabolic Health status in a federally qualified community health center patient population. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2021;21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-02149-5

Radhakrishnan K, Jacelon CS, Bigelow C, Roche J, Marquard J, Bowles KH. Use of a homecare electronic health record to find associations between patient characteristics and re-hospitalizations in patients with heart failure using telehealth. J Telemed Telecare. 2013;19(2):107–112. https://doi.org/10.1258/2Fjtt.2012.120509

Ye C, Fu T, Hao S, Zhang Y, Wang O, Jin B, et al. Prediction of incident hypertension within the next year: prospective study using statewide Electronic Health Records and machine learning. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(1): e22. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9268.

Du Z, Yang Y, Zheng J, Li Q, Lin D, Li Y, et al. Accurate prediction of coronary heart disease for patients with hypertension from Electronic Health Records with big data and machine-learning methods: model development and performance evaluation. JMIR Med Inform. 2020;8(7): e17257. https://doi.org/10.2196/17257.

Shuey MM, Gandelman JS, Chung CP, Nian H, Yu C, Denny JC, et al. Characteristics and treatment of African-American and European-American patients with resistant hypertension identified using the electronic health record in an academic health centre: a case−control study. BMJ Open. 2018;8: e021640. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021640.

Newton-Dame R, McVeigh KH, Schreibstein L, et al. Design of the New York City macroscope: innovations in population health surveillance using electronic health records. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2016;4(1):1265. https://doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1265

Lu Y, Huang C, Mahajan S, et al. Leveraging the electronic health records for Population Health: a case study of patients with markedly elevated blood pressure. J Am Heart Asso. 2020;9(7). https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.119.015033

• Jaffe MG, Lee GA, Young JD, Sidney S, Go AS. Improved blood pressure control associated with a large-scale hypertension program. JAMA. 2013;310(7):699. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.108769. An exemplar population health management intervention that leveraged an electronic health record enabled registry to improve hypertension outcomes.

Glynn LG, Murphy AW, Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Interventions used to improve control of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd005182.pub4.

Cordasco KM, Hynes DM, Mattocks KM, Bastian LA, Bosworth HB, Atkins D. Improving care coordination for veterans within VA and across Healthcare Systems. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(S1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04999-4.

Jaffe DH, Lee L, Huynh S, Haskell TP. Health inequalities in the use of telehealth in the United States in the lens of COVID-19. Popul Health Manag. 2020;23:368–77.

Ye S, Kronish I, Fleck E, et al. Telemedicine expansion during the COVID-19 pandemic and the potential for technology-driven disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;36:256–8.

Bauerly BC, McCord RF, Hulkower R, Pepin D. Broadband access as a public health issue: The role of law in expanding broadband access and connecting underserved communities for better health outcomes. J Law Med Ethics 2019;47(2_Suppl.):39–42.

Goodman CW, Brett AS. Accessibility of virtual visits for urgent care among us hospitals: a descriptive analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05888-x.

Donelan K, Barreto EA, Sossong S, et al. Patient and clinician experiences with telehealth for patient follow-up care. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(1):40–4.

Stevenson L, Ball S, Haverhals LM, Aron DC, Lowery J. Evaluation of a national telemedicine initiative in the Veterans Health Administration: factors associated with successful implementation. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(3):168–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X16677676.

Lum HD, et al. “Anywhere to anywhere: use of telehealth to increase health care access for older, rural veterans.” Public Policy & Aging Report 30.1 (2020); 12–18.

•• Jazowski SA, Bosworth HB, Goldstein KM, White-Clark C, McCant F, Gierisch JM, et al. Implementing a population health management intervention to control cardiovascular disease risk factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1931–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05679-4. A population health management intervention that combines best practices related to telehealth, electronic health record capabilities, and team-based care to improve hypertension outcomes in a Veteran population.

• Mulrooney M, Smith M, Lewis K, et al. Practical implementation insights from 2 Population Health Pharmacist Project approaches to improve blood pressure control. J Am Pharm. 2022;62(1):270–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2021.07.012. An exemplar population health management intervention that uses the electronic health record to identify hypertensive patients likely to disproportionately benefit from proactive outreach by population health pharmacists. Implementation considerations are presented and discussed.

Bain NSC, Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Cassidy J. Striking the right balance in colorectal cancer care–a qualitative study of rural and urban patients. Fam Pract. 2002;19(4):369–74.

Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Yearb Med Inform. 2000;09(01):65–70. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1637943.

Stirman SW, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The frame: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science. 2019;14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y

Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder J, Calloway A. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2013;8:65. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-65.

Drake C, Lewinski A, Zullig L. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). In. The International Encyclopedia of Health Communication: Wiley; 2021. In press. Accepted January 26, 2021.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Funding

The research reported in this publication was supported by Office of Rural Health Award grant #ORH 14379; Durham Center of Innovation to Accelerate Discovery and Practice Transformation grant #CIN 13–410; Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations grant #TPH 21–000 (to AAL); VA HSR&D grants #08–027 (to HBB) and #18–234 (to AAL); and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health award number K12HL138030 (to CD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CD, LLZ, AAL, KMG, JS, and HBB contributed to the study conception, framing, and design. AAL, LLZ, KMG, FM, JG, and CW contributed to the data preparation and extraction, and CD, AAL, JS, KMG, AR, HBB, and LLZ contributed to data interpretation and narrative literature review. The first draft of the article was written by CD, AAL, and LLZ. All authors read and approved the final article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The study described has been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and has been performed in accordance with ethical standards from the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and later amendments. All persons who participated in the study gave informed consent prior to consent and have had identifying information omitted.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Drake reports receiving funds from ZealCare. Dr. Lewinski reports receiving funding from the PhRMA Foundation and Otsuka. Dr. Bosworth reports receiving research funds from Sanofi, Otsuka, Johnson and Johnson, Improved Patient Outcomes, Novo Nordisk, PhRMA Foundation as well as consulting funds from Walmart, Webmed, Sanofi, Otsuka, Abbott, and Novartis. Dr. Zullig reports receiving funding from the PhRMA Foundation and Proteus Digital Health as well as consulting funds from Novartis and Pfizer. The remaining authors have no competing interests to declare. The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the author(s) who are responsible for its contents and do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the US Government, or Duke University. Therefore, no statement in this article should be construed as an official position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Duke University.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Telemedicine and Technology

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Drake, C., Lewinski, A.A., Rader, A. et al. Addressing Hypertension Outcomes Using Telehealth and Population Health Managers: Adaptations and Implementation Considerations. Curr Hypertens Rep 24, 267–284 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-022-01193-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-022-01193-6