Abstract

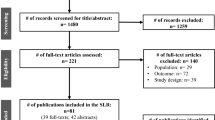

For patients hospitalized with acute heart failure, health policy initiatives in the USA have drawn attention to 30-day mortality and readmission. Confusion around definitions, populations, and thus reported rates for these two outcomes is common. Among Medicare fee-for-service patients hospitalized with heart failure, all-cause mortality 30 days from the time of admission is 11.7 % and all-cause unplanned readmission 30 days from discharge is 23.0 %. Rates for Medicaid and commercially insured patients are lower. Mortality rates have been relatively stable, while readmission rates increased under the Diagnosis Related Group payment system then began decreasing under the Hospital Readmission Reductions Program. Risk models are reasonable at predicting mortality, whereas readmission has been harder to anticipate. The use of risk-standardized hospital rates as performance measures has generated considerable debate. Future work should clarify the interaction between the two measures, the optimal time window and factors influencing rates and trends—including socioeconomic status.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, “Report to the Congress: promoting greater efficiency in Medicare,” June 2007. Accessed May18, 2014 from http://www.medpac.gov/documents/jun07_entirereport.pdf

Department of Health and Human Services. “Hospital compare.” Accessed May 24, 2014 from www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. The Hospital Compare website is a resource for the most updated data from over 4,000 Medicare-certified hospitals regarding mortality and readmission rates (among others) in the United States.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “Readmissions reduction program.” Accessed May 18, 2014 from http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “Bundled payments for care improvement (BPCI) initiative. Accessed June 4th, 2014 from http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/

Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;128.

Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:606–19.

Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. NEJM. 2013;368:100–2.

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:1810–52.

McMurray M, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:803–69.

Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–28.

Fisher ES, Wennberg JE, Stukel TA, Sharp SM. Hospital readmission rates for cohorts of Medicare beneficiaries in Boston and New Haven. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:989–95.

Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Hellermann-Homan JP, Killian J, Yawn BP, et al. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004;292:344–50.

Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Report. Hyattsville. MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013.

Burton R. Health policy brief: care transitions. Health Affairs. 2012(September 13).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed mortality file: underlying cause of death. CDC WONDER Online Database [database online]. Released January 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed June 20th, 2014 from http://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQl.html.

Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998–2008. JAMA. 2011;306:1669–78. Analysis of a large cohort of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries showing that overall rates of risk-adjusted hospitalization for heart failure declined 30% from 1998 to 2008; in contrast, over the same period, 1-year risk-adjusted all-cause mortality rate after heart failure hospitalization remained high at approximately 30%. Rehospitalization rates remained unchanged or even increased over a similar time frame.

Krumholz HM, Normand SL, Spertus JA, Shahian DM, Bradley EH. Measuring performance for treating heart attacks and heart failure: the case for outcomes measurement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26:75–85.

Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Zhenqiu L, et al. Diagnosis and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309:3555–63.

Bueno H, Ross JS, Wang Y, Chen J, Vidan MT, Normand SL, et al. Trends in length of stay and short-term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006. JAMA. 2010;303:2141–7.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Accessed June 18th, 2014 from http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html

US Department of Health and Human Services. New HHS data shows major strikes made in patient safety, leading to improved care and savings. May 7th, 2014.

Krumholz HM, Merrill AR, Schone EM, Schreiner GC, Chen J, Bradley EH, et al. Patterns of hospital performance in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure 30-day mortality and readmission. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:407–13.

Konstam MA, Gheorghiade M, Burnett Jr JC, Grinfeld L, Maggioni AP, Swedberg K, et al. Effects of oral tolvaptan in patients hospitalized for worsening heart failure: the EVEREST outcome trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1319–31.

O’Connor CM, Starling RC, Hernandez AF, Armstrong PW, Dickstein K, Hasselblad V, et al. Effect of nesiritide in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:32–43.

Squires DA. The U.S. health system in perspective: a comparison of twelve industrialized nations. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2011:16:1–14.

Hammill BG, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC, Schulman KA, Curtis LH. Linking inpatient clinical registry data to Medicare claims data using indirect identifiers. Am Heart J. 2009;157:995–1000.

Blair JE, Zannad F, Konstam MA, Cook T, Traver B, Burnett Jr JC, et al. Continental differences in clinical characteristics, management, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with worsening heart failure results from the EVEREST (Efficacy of Vasopressin Antagonism in Heart Failure: Outcome Study with Tolvaptan) program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1640–8.

West R, Liang L, Fonarow GC, Kociol R, Mills RM, O’Connor CM, et al. Characterization of heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: a comparison between ADHERE-US registry and ADHERE-international registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:945–52.

Allen LA, Smoyer Tomic KE, Smith DM, Wilson KL, Agodoa I. Rates and predictors of 30-day readmission among commercially insured and Medicaid-enrolled patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2012;672–9. One of very few analyses assessing readmission data in non-Medicare populations. Administrative claims from the MarketScan Commercial and Medicaid Databases were used to identify all first hospitalizations with a discharge diagnosis code for heart failure between 2005–2008. Among patients with a mean age 55 years, all-cause 30-day crude readmission rates were 17.4% for Medicaid patients and 11.8% for commercially insured patients

Eapen ZJ, Reed SD, Li Y, Kociol RD, Armstrong PW, Starling RC, et al. Do countries or hospitals with longer hospital stays for acute heart failure have lower readmission rates?: findings from ASCEND-HF. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:727–32.

Fonarow GC, Adams Jr KF, Abraham WT, Yancy CW, Boscardin WJ. Risk stratification for in-hospital mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure: classification and regression tree analysis. JAMA. 2005;293:572–80.

Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and risk stratification in acute heart failure. Am Heart J. 2008;155:200–7.

Abraham WT, Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients hospitalized for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:347–56.

O’Connor CM, Hasselblad V, Mehta RH, Tasissa G, Califf RM, Fiuzat M, et al. Triage after hospitalization with advanced heart failure: the ESCAPE (Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness) risk model and discharge score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:872–8.

Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, Cropp AB, et al. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: predication of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1424–33.

Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, Kagen D, Theobald C, Freeman M, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306:1688–98. A systematic review summarizing validated readmission risk prediction models. Twenty-six unique readmission models were identified, with the most common outcome being 30-day readmission.

Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, Wang Y, Han LF, Ingber MJ, et al. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1693–701.

Zhang W, Watanabe-Galloway S. Ten-year secular trends for congestive heart failure hospitalizations: an analysis of regional differences in the United States. Congest Heart Fail. 2008;14:266–71.

Hammill BG, Curtis LH, Fonarow GC, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, Peterson ED, et al. Incremental value of clinical data beyond claims data in predicting 30-day outcomes after heart failure hospitalization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:60–7.

Hersh AM, Masoudi FA, Allen LA. Postdischarge environment following heart failure hospitalization: expanding the view of hospital readmission. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000116.

Gorodeski EZ, Starling RC, Blackstone EH. Are all readmission bad readmissions? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:297–8.

Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Keenan PS, Chen J, Ross JS, Drye EE, et al. Relationship between hospital readmission and mortality rates for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309:587–93. An analysis of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries discharged with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia between 2005–2008, which found hospital 30-day risk-standardized mortality rates were minimally associated with risk-standardized readmission rates.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “Hospital value-based purchasing.” Accessed June 1st, 2014 from http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/index.html?redirect=/hospital-value-based-purchasing

Gamble JM, Eurich DT, Ezekowitz JA, Kaul P, Quan H, McAlister FA. Patterns of care and outcomes differ for urban vs rural patients with newly diagnosed heart failure, even in a universal healthcare system. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:317–23.

Foraker RE, Rose KM, Suchindran CM, Chang PP, McNeill AM, Rosamond WD. Socioeconomic status, Medicaid coverage, clinical comorbidity, and rehospitalization or death after an incident heart failure hospitalization: atherosclerosis risk in communities cohort (1987 to 2004). Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:308–16.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Morbidity and mortality: 2012 chart book on cardiovascular, lung, and blood diseases. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2012

Zannad F, Garcia AA, Anker SD, Armstrong PW, Calvo G, Cleland JG, et al. Clinical endpoints in heart failure trials: a European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association consensus document. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1082–94.

Acknowledgments

Larry A. Allen is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Grant # K23HL105896).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Colleen K. McIlvennan declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Larry A. Allen has received compensation from Amgen for service on a scientific advisory panel and compensation from Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals for service on a steering committee.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McIlvennan, C.K., Allen, L.A. Outcomes in Acute Heart Failure: 30-Day Readmission Versus Death. Curr Heart Fail Rep 11, 445–452 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-014-0215-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-014-0215-7