Abstract

The Job Demands-Resources model postulates job resources to directly promote employees’ mental health and to interact with job demands. Recent meta-analyses revealed differential effects of social and organizational resources. Studies of job resources in police officers predominantly included social resources and have rarely examined differential effects, interaction effects, and both negative and positive mental health outcomes. The present study provides a comprehensive test of job resources for the mental health of police officers: Main and interaction effects of social and organizational resources were tested on burnout symptoms and job satisfaction. Survey data were collected from 493 German police officers. Social (support, sense of community, leadership quality) and organizational resources (influence at work, possibilities for development, meaning of work), demands (quantitative, emotional, work privacy conflicts), burnout symptoms, and job satisfaction were assessed with an online questionnaire. Stepwise regression analyses and moderator analyses (PROCESS) were performed. Job resources contributed to the prediction of burnout symptoms and job satisfaction beyond job demands. Organizational resources explained substantial variance beyond social resources. Sense of community and possibilities for development were the most influential resources, and work privacy conflicts were the most influential demand. In addition, work privacy conflicts strengthened the association between sense of community and job satisfaction. The study confirms that social as well as organizational resources are protective for police officers’ mental health. Sense of community and possibilities for development emerged as promising starting points for measures to prevent burnout and promote job satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The daily work of police officers involves various and challenging operational and organizational demands (Collins and Gibbs 2003; Galanis et al. 2021; Violanti et al. 2017). Some of them (e.g., workload, shift work, emotional demands) are partly unchangeable or hardly influenceable in police work and are considered risk factors for the mental health of police officers. However, police work also involves health-promoting factors, namely, job resources such as autonomy or social support. The Job Demands-Resources model (JD-R model) postulates job resources to promote employees’ mental health and interaction effects with job demands (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Demerouti et al. 2001; Demerouti and Nachreiner 2019). Recent meta-analyses distinguished social from organizational resources and revealed differential effects on positive indicators of mental health (Gusy et al. 2020; Lesener et al. 2020). Studies of job resources in the police have rarely examined different subcategories of resources (Hu et al. 2016), interaction effects (Santa Maria et al. 2018), and positive mental health outcomes (Hu et al. 2016; van den Broeck et al. 2010; Wolter et al. 2019b). The present study extends the existing literature by differentiating between social and organizational resources and examining their predictions beyond job demands for a negative and a positive mental health outcome. Moreover, it investigates the differential and interaction effects of job resources.

The Job Demands-Resources Model

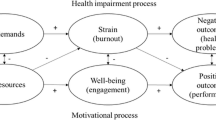

Job characteristics and their effects on employees’ mental health are described and investigated within several theoretical frameworks. The Job Demands-Resources model (JD-R model; Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Demerouti et al. 2001; Demerouti and Nachreiner 2019) is one of the most popular and empirically validated (Schaufeli and Taris 2014). It comprises two main assumptions.

Firstly, the model assumes that all job characteristics can be classified in two broad categories that can be applied to any occupational context. Job demands are defined as “physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and psychological costs” (Demerouti et al. 2001, p. 501). Schaufeli (2017) refers to them as “the ‘bad things’ at work” (p. 121). Examples are workload and time pressure, emotional demands, or role conflicts. Job resources, in contrast, are seen as “the ‘good things’ [at work]” (Schaufeli 2017, p. 121) that “refer to physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that may do any of the following: (a) be functional in achieving work goals, (b) reduce job demands at the associated physiological and psychological costs; (c) stimulate personal growth and development” (Demerouti et al. 2001, p. 501). Examples include support at work, autonomy, or role clarity.

Secondly, the model assumes that job demands and job resources are involved in two different processes affecting employees’ mental health and further consequences (Bakker and Demerouti 2007). In the first health impairment process, job demands predict negative mental health outcomes such as burnout which in turn may lead to reduced performance or turnover intention. In the second motivational process, job resources promote positive mental health outcomes (e.g., work engagement, job satisfaction) which in turn may foster organizational commitment or performance (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Demerouti et al. 2001; Demerouti and Nachreiner 2019). The JD-R model further states that poor job resources directly contribute to burnout (Schaufeli and Taris 2014). Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence across different occupations and workplaces confirms the postulated main effects of job demands and job resources (Crawford et al. 2010; Lesener et al. 2019; Schaufeli and Taris 2014).

Moreover, the JD-R model hypothesizes interaction effects of job demands and job resources (Demerouti and Nachreiner 2019). In particular, the health-promoting effect of job resources should be moderated by job demands. In addition, job resources should buffer the negative impact of job demands on burnout by supporting employees in being able to cope with the daily demands of their work (Bakker and Demerouti 2007). Support at work, for example, is such a resource which should have a buffer effect (Johnson and Hall 1988). Overall, there are only few studies on the two interaction effects. If anything, the buffer effect of resources was examined (Bakker et al. 2005; Xanthopoulou et al. 2007). These studies confirmed that several job resources (e.g., autonomy, performance feedback, support at work) weakened the association between job demands (e.g., workload, emotional demands, work home interference, physical demands) and burnout.

Job Resources in Police Officers

Several studies have applied the JD-R model to the context of police work. All of them considered negative mental health outcomes (Frank et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2016; Martinussen et al. 2007; Santa Maria et al. 2018; van den Broeck et al. 2010; Wolter et al. 2019b). Regarding job resources, those studies confirmed the postulated negative association between several job resources (e.g., social and organizational support, shared values, positive leadership climate) and burnout, emotional exhaustion, and work stress. Some studies have also examined positive mental health outcomes (Hu et al. 2016; van den Broeck et al. 2010; Wolter et al. 2019b). They found job resources such as support at work, shared values, or autonomy to promote job engagement or vigor and the general well-being.

To our knowledge, the interaction effects of the JD-R model have only been examined in one study for police officers (Santa Maria et al. 2018). It tested the buffering hypothesis and confirmed job resources (support by colleagues, shared values, and positive leadership climate) to weaken the association between job demands and emotional exhaustion. No study was found on job demands moderating the association between job resources and positive outcomes among police officers.

In summary, the state of research based on the JD-R model shows that job resources, in addition to job demands, have an important role in predicting police officers’ mental health. However, positive outcomes have been examined less frequently than negative outcomes, and interaction effects have been examined less frequently than main effects.

Subcategories of Job Resources

In the introduction of the JD-R model, Demerouti et al. (2001) described different subcategories of job resources. Based on Udris et al. (1992), they distinguished internal and external resources, but excluded internal resources due to the uncertainty as to which they are stable and changeable at all by work design (Demerouti et al. 2001). The authors thus understood job resources as external resources which can be either organizational (e.g., autonomy, job variety, participation in decision making) or social in nature (e.g., support from colleagues or supervisors). The subdivision, however, did not find its way into the JD-R model and related research. This applies also to the studies on police officers: They included job resources from the two subcategories but did not take this into account in the analyses (Frank et al. 2017; Martinussen et al. 2007; Santa Maria et al. 2018; van den Broeck et al. 2010; Wolter et al. 2019b).

Two recent meta-analyses provided a more differentiated view of job resources within the JD-R model (Gusy et al. 2020; Lesener et al. 2020). They differentiated social resources from organizational or work-related resources and analyzed their impact on positive mental health outcomes such as job engagement and job satisfaction. In result, organizational resources (e.g., autonomy, development opportunities, role clarity) had a stronger impact on work engagement than social resources (e.g., support by colleagues and supervisors, support climate). For job satisfaction, social resources were somewhat more predictive than organizational resources (Gusy et al. 2020).

Only one study on police officers, to our knowledge, examined different subcategories of job resources (Hu et al. 2016). It differentiated task resources (job control and participation in decision making) and support from colleagues and from the supervisor and investigated their influence on burnout and work engagement: Task resources were found to be relevant in the prevention of burnout and in the promotion of work engagement, whereas social resources were predictive only for work engagement. These results underscore the importance of task resources for negative and positive mental health even though social resources had a stronger effect on the positive outcome on work engagement.

Against this backdrop, the other studies included primarily indicators from the subcategory of social resources (Frank et al. 2017; Martinussen et al. 2007; Santa Maria et al. 2018; van den Broeck et al. 2010; Wolter et al. 2019b). Organizational resources were considered only in three studies (Frank et al. 2017; Martinussen et al. 2007; van den Broeck et al. 2010). Two used autonomy as a single indicator (Martinussen et al. 2007; van den Broeck et al. 2010). None of these studies were interested in the differential effects of social and organizational resources.

It can be concluded that social and organizational resources seem to play a different role and organizational resources may be highly important in general and in the police. Organizational resources are considered in few studies of police officers to date, and only one examined them as a specific subcategory (Hu et al. 2016). Any differential effects may be neglected. We propose therefore further research on subcategories of job resources and differential effects within the JD-R model. This approach would allow to provide evidence for further theory development as well as resource-specific health promotion interventions in the workplace.

Present Research

The present study aimed at extending the literature on job resources with the JD-R model: Based on Udris et al. (1992) and Demerouti et al. (2001), job resources were further differentiated into social and organizational resources. It was outlined that studies on police officers predominantly examined the effects of social resources. Studies which compared the two subcategories imply however organizational resources to be highly important for mental health. Of particular interest was thus the unique contribution of organizational resources over and above social resources. Furthermore, the differential effects of the specific job resources and interaction effects were examined for a negative and a positive mental health outcome (i.e., burnout symptoms and job satisfaction). Support at work, sense of community, and quality of leadership were included as social resources, and influence at work, possibilities for development, and meaning of work as organizational resources. Quantitative demands, emotional demands, and work privacy conflicts were included as job demands due to their relevance for mental health among police officers (Collins and Gibbs 2003; Galanis et al. 2021; Martinussen et al. 2007; Santa Maria et al. 2018; van den Broeck et al. 2010; Violanti et al. 2017; Wolter et al. 2019b).

Four research questions were stated: (1) Do job resources explain unique variance in the outcomes over and above job demands and control variables, and do organizational resources specifically explain variance over and above social resources? (2) Which specific social and organizational resources contribute significantly to the predictions? (3) Is the association between job resources and job satisfaction moderated by job demands? (4) Do job resources buffer the association between job demands and burnout symptoms?

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 493 uniformed police officers who took part in the health survey in a German police headquarters (N = 995) and provided complete data on the study variables. All employees had been informed about the aim of the health survey, anonymity, voluntariness, and data protection, and received the link to an online questionnaire. Employees without internet access at work were provided a paper–pencil version of the questionnaire. Five employees took advantage of this possibility. The health survey had been approved by the institutional ethics committee.

The study sample consisted of 364 male (74%) and 129 female (26%) police officers. The age distribution is shown in Table 1. The police officers were more likely to work full-time (90%) and in an alternating shift service (52%); one of four had a leadership role (25%).

Study Variables

Job demands, social resources, organizational resources, as well as mental health outcomes were measured with the German standard version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ, Lincke et al. 2021). The COPSOQ is a valid and reliable instrument for research on work and health and for occupational risk assessment (Burr et al. 2019). It has been applied to various occupations and workplaces and is widely used in research. Two measures were slightly modified to be more suitable for the sample and the job characteristics: One item each was replaced by an item from an older version of the instrument (2014; emotional demands) or deleted (job satisfaction). All items were rated on 5-point Likert-type scales with values from 0 to 100. Study variables were calculated by taking the mean. Means, standard deviations, and internal consistencies are shown in Table 2.

Job Demands

Quantitative demands were assessed by rating the frequency of five specific demands (e.g., “Do you have to work very fast?”; 0 = never/hardly ever to 100 = always). Emotional demands were reported by two items (e.g., “Is your work emotionally demanding?”) and work privacy conflicts by four items (e.g., “The demands of my work interfere with my private and family life.”) asking for the extent of these demands (0 = to a very small extent to 100 = to a very large extent).

Social Resources

Support at work and sense of community at work were reported by frequency ratings (0 = never/hardly ever to 100 = always). Support comprises two items on support from colleagues and two items on support from the immediate superior (“How often do you get help and support from […], if needed?”, “How often are / is your […] willing to listen to your problems at work, if needed?”). Sense of community at work refers to colleagues and includes two items (e.g., “Is there a good atmosphere between the colleagues at work?”). Quality of leadership was assessed by asking the respondents to rate four different behaviors of their immediate superior (e.g., “To what extent would you say that your immediate superior is good at planning work?”; 0 = to a very small extent to 100 = to a very large extent).

Organizational Resources

Influence at work was assessed by three frequency ratings (e.g., “Do you have a large degree of influence on the decisions concerning your work?”; 0 = never/hardly ever to 100 = always) as well as the first item of possibilities for development (“Is your work varied?”). The other two items of possibilities for development (e.g., “Do you have the possibility of learning new things through your work?”) and meaning of work (two items, e.g. “Is your work meaningful?”) were ratings of the extent of different aspects of these constructs (0 = to a very small extent to 100 = to a very large extent).

Mental Health

Burnout symptoms were assessed as a negative outcome. The measure consists of three symptom items whose frequency is rated from never/hardly ever (0) to always (100; e.g., “How often do you feel physically exhausted?”). Job satisfaction was chosen as a positive outcome (Gusy et al. 2020). The measure asks how satisfied the respondents are with six work-related issues (e.g., “How pleased are you with your work prospects?”; 0 = highly unsatisfied to 100 = very satisfied).

Additional Variables

Sex and age, and the job characteristics full-time work (yes; no), supervisor position (yes; no), and working time model (day service; alternating shift service; time shifted service, incl. evenings and weekends) were asked to describe the sample.

Data Analysis

The analyses were performed using SPSS 27.

The first research question was examined by hierarchical regression analyses to test the predictive value of the two subcategories of job resources for burnout symptoms and job satisfaction. The first step included sex and age as possible control variables, followed by the job demands in the second step. In the third and fourth steps, the social and organizational resources were entered, respectively, to test whether job resources account for unique variance in the outcomes over and above the control variables, job demands, and over and above social resources in the case of the organizational resources.

To answer the second research question, which job resources significantly contribute to the predictions, the unique effects of the resources were determined.

The third and fourth research questions were tested by moderation analyses using PROCESS (Hayes 2018). Based on the previous regression analyses, the two job resources and the one job demand with the strongest main effects were selected and tested for interaction effects. The remaining demands and resources as well as the control variables from the previous regression models were entered as covariates. All variables of the interaction terms were centered. Significant interaction effects were further investigated by simple slopes analyses: Conditional effects of the predictor variable on the outcome in question were estimated and visualized at different values of the moderator(s) and tested whether the conditional effects were different from zero.

Results

The intercorrelations of the study variables are shown in Table 2. Burnout symptoms and job satisfaction were negatively and significantly associated (r = -0.42, p < 0.01). The more burnout symptoms the participants had, the less satisfied they were with their job.

All job demands and job resources significantly correlated with the two outcomes. The more job demands and the fewer social and organizational resources the participants reported, the more burnout symptoms and lower job satisfaction they had.

The three job demands were significantly associated. For example, the higher the quantitative and emotional demands, the more work privacy conflicts (rs > 0.43, ps < 0.01). The three social resources also significantly correlated, e.g., the more social support and higher the quality of leadership, the higher the sense of community at work (rs > 0.44, ps < 0.01). Likewise, the three organizational resources were significantly associated, e.g., the more meaning of work (r = 0.53, p < 0.01) and more influence at work (r = 0.26, p < 0.01), the more the possibilities for development.

Contribution of Social and Organizational Resources

The first research question was whether job resources explain unique variance in the outcomes over and above job demands and control variables, and whether organizational resources specifically explain variance over and above social resources.

Table 3 presents the results of the hierarchical regression analyses for the two outcome measures. The overall models with all variables were significant. They explained 37% of the variance in burnout symptoms, F(11, 481) = 25.91, p < 0.001, and 54% of the variance in job satisfaction, F(11, 481) = 50.77, p < 0.001.

The control variables significantly accounted for variance only in burnout symptoms, ΔR2 = 0.07, F(2, 490) = 17.71, p < 0.001, but not in job satisfaction, ΔR2 = 0.00, F(2, 490) = 0.28, p < 0.001. Burnout symptoms thus increased across the age groups.

Adding job demands in the second step of the analyses contributed significantly to the prediction of burnout symptoms, ΔR2 = 0.22, F(3, 487) = 49.32, p < 0.001, and job satisfaction, ΔR = 0.19, F(3, 487) = 39.22, p < 0.001. In specific, work privacy conflicts significantly predicted burnout symptoms, ΔR2 = 0.11, F(1, 487) = 74.08, p < 0.001. Work privacy conflicts were also the job demand with the strongest effect on job satisfaction, ΔR2 = 0.11, F(1, 487) = 67.90, p < 0.001, which was significantly predicted by emotional demands too, ΔR2 = 0.01, F(1, 487) = 6.54, p < 0.01. That is, the more conflicts the police officers perceived between their work and private life, the more burnout symptoms and less satisfied they were with their job. They were also less satisfied with their job the more emotionally demanding it was perceived.

Entering the third step supported the predictive value of the social resources for both outcomes. The amount of the explained variance increased by 5% in burnout symptoms, F(3, 484) = 12.62, p < 0.001, and by 23% in job satisfaction, F(3, 484) = 64.86, p < 0.001.

Adding the fourth step showed that organizational resources had predictive value too: They accounted for a further 4% variance in burnout symptoms, F(3, 481) = 9.05, p < 0.001, and 11% in job satisfaction, F(3, 481) = 38.49, p < 0.001.

Differential Effects of Job Resources

The second research question addressed the differential effects of the job resources by asking which specific job resources have significant main effects on the mental health outcomes. The change in R2 for each job resource variable is presented in Table 3.

In the case of social resources, sense of community was the strongest predictor of burnout symptoms, ΔR2 = 0.03, F(1, 484) = 18.67, p < 0.001, and job satisfaction, ΔR2 = 0.06, F(1, 484) = 46.20, p < 0.001. Quality of leadership, in addition, significantly predicted job satisfaction, ΔR2 = 0.04, F(1, 484) = 34.59, p < 0.001. The more sense of community the police officers perceived, the fewer burnout symptoms and higher job satisfaction they reported. They were also more satisfied the better the quality of leadership was.

Regarding organizational resources, possibilities for development was a significant predictor of burnout symptoms, ΔR2 = 0.02, F(1, 481) = 12.41, p < 0.001. It was the strongest predictor for job satisfaction too, ΔR2 = 0.04, F(1, 481) = 38.19, p < 0.001, which was also predicted by influence at work, ΔR 2 = 0.01, F(1, 481) = 12.01, p < 0.001, and meaning of work, ΔR2 = 0.01, F(1, 481) = 9.74, p < 0.001.

Moderation Effects on Job Satisfaction

The third research question regarded the moderation of the effects of job resources on job satisfaction by job demands. Sense of community at work and possibilities for development were the social and organizational resources, respectively, with the strongest effects on job satisfaction and were thus examined for potential interaction effects (PROCESS model 1). The interaction effects were tested with the job demand work privacy conflicts as it was the demand with the strongest effect on job satisfaction. The remaining job demands, job resources, and the control variables were entered as covariates. With sense of community at work, the overall model, R2 = 0.53, F(11, 481) = 49.63, p < 0.001, and the addition of the interaction term, ΔR2 = 0.01, F(1, 481) = 6.05, p < 0.05, were significant. The interaction increased the amount of the explained variance in job satisfaction by 1%, indicating that the health-promoting effect of sense of community at work depends on the extent of work privacy conflicts.

To further investigate the interaction, conditional effects of sense of community at work on job satisfaction at different levels of work privacy conflicts were estimated. Figure 1 shows the results of the simple slope analyses. Sense of community at work was positively and stronger associated with job satisfaction among those with more work privacy conflicts (+ 1 SD: B = 0.24, t(480) = 5.01, p < 0.001) than among those with less conflicts (− 1 SD: B = 0.11, t(480) = 2.50, p < 0.05). A low sense of community at work reduced job satisfaction more in the case of more than less conflicts between work and private life.

With possibilities for development, the overall model was significant, R2 = 0.53, F(11, 481) = 48.56, p < 0.001, but the addition of the interaction term did not increase the amount of the explained variance, ΔR2 = 0.00, F(1, 481) = 0.44, p > 0.10.

Buffer Effects on Burnout Symptoms

With respect to the fourth research question of buffer effects of job resources on burnout symptoms, PROCESS (model 2) was used. Sense of community at work and possibilities for development were the social and organizational resources with significant effects and thus examined as potential moderators. The buffer effects were again tested for work privacy conflicts which were the only job demand with significant effect and controlled for effects of the remaining job demands, resources, and the control variables. The overall model with all predictors was significant, R2 = 0.37, F(12, 480) = 24.01, p < 0.001, but the addition of the two interaction terms did not increase the amount of explained variance, ΔR2 = 0.00, F(2, 480) = 1.20, p > 0.10.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to provide a more nuanced view of police officers’ job resources. The JD-R model (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Demerouti et al. 2001; Demerouti and Nachreiner 2019) was chosen as the theoretical framework: It assumes that job demands and job resources are important for the prediction of employees’ mental health. It postulates both main and interaction effects on negative and positive mental health outcomes. Recent meta-analyses revealed differential effects of subcategories of job resources on positive mental health outcomes (Gusy et al. 2020; Lesener et al. 2020). However, little was known so far about the differential effects of subcategories of job resources and specific resources among police officers (Hu et al. 2016). We therefore propose to differentiate subcategories of job resources and to examine the differential effects within the JD-R model. Both main (research questions 1 and 2) and interaction effects (research questions 3 and 4) of social and organizational resources were tested over and above the effects of job demands and control variables. Burnout symptoms and job satisfaction were chosen as negative and positive mental health indicators.

Regarding the first research question, job resources were found to have an impact on the considered outcomes over and above job demands and control variables. Most studies on police officers included social resources and predominately examined the effect of social support on mental health (Frank et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2016; Martinussen et al. 2007; Santa Maria et al. 2018; van den Broeck et al. 2010; Wolter et al. 2019b). Organizational resources have hardly been studied, and if so, then only autonomy and influence (Frank et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2016; Martinussen et al. 2007; van den Broeck et al. 2010). Only one study, however, was interested in the differential effects of the two subcategories of job resources (Hu et al. 2016).

The present study confirmed their effects on burnout symptoms and job satisfaction. The absolute proportion of explained variance, however, was twice as high for job satisfaction as for burnout symptoms (Lincke et al. 2021). Social resources explained 5% and 23% of the variance, respectively. Organizational resources accounted for an additional 4% and 11% of the variance. Thus, organizational resources had just as much explanatory power as social resources for burnout symptoms and at least half as much for job satisfaction in comparison. Nevertheless, organizational resources explain a substantial amount of variance in mental health. This finding shows that social and organizational resources should be considered separately within the JD-R model and related research. Furthermore, organizational resources have unique effects above social resources and should therefore receive more attention within the JD-R model and related studies in the police context.

The second research question related to the specific job resources with significant effects in order to provide evidence for resource-specific health promotion interventions in the police. Based on previous research and their potential relevance to police officers, three social and organizational resources each were included and tested for their unique contribution to the prediction of a negative and positive mental health outcome. Sense of community at work and possibilities for development were the resources with the strongest effects and with effects on both, burnout symptoms and job satisfaction.

The social resource sense of community at work represented the most influential job resource in our study. It contributed 3% and 6% of the variance in burnout symptoms and job satisfaction, respectively. Support at work did not contribute significantly to the predictions, but the quality of leadership contributed to the prediction of job satisfaction. Sense of community has hardly been investigated in previous studies among police officers; there is only one study on team support (Wolter et al. 2019b). The influence of leaders was examined by Santa Maria et al. (2018) in terms of leadership climate. The most frequently examined social resource was rather support at work for which beneficial effects were found on mental health (Hu et al. 2016; Martinussen et al. 2007; Santa Maria et al. 2018; van den Broeck et al. 2010). These previous studies however all included a different number and selection of job resources. Furthermore, they used either regression analyses (Frank et al. 2017; Martinussen et al. 2007) or structural equation modeling (Santa Maria et al. 2018; van den Broeck et al. 2010; Wolter et al. 2019b). The latter studies combined the specific job resources into one latent factor and analyzed its predictive power for the outcomes studied. The predictive power of the individual resources for the factor is reported, with one exception (van den Broeck et al. 2010). Nevertheless, job resources are regarded as being unidimensional and global, thereby overlooking potential differential effects of subcategories of job resources or specific job resources. Team support, for example, was investigated together with shared values and perceived fairness as a latent factor and had the lowest predictive value for the factor (Wolter et al. 2019b). Furthermore, social support, leadership climate, and shared values were examined together as a factor with social support having the lowest predictive value (Santa Maria et al. 2018). Another study combined the two resources autonomy and social support without reporting their predictive values for the factor (van den Broeck et al. 2010). The two studies which tested job resources as independent variables within regression analyses, however, only looked at negative outcomes (Frank et al. 2017; Martinussen et al. 2007).

Consequently, the results of the present study are difficult to compare. Particularly with regard to support at work, our results seem to contradict the current state of research, according to which social support is proven to be beneficial to the mental health of police officers (Hu et al. 2016; Martinussen et al. 2007; Santa Maria et al. 2018). However, support at work has so far never been studied together with sense of community at work. As both social resources overlap in content and are also closely related empirically (r = 0.65), the questions arise as to whether sense of community actually plays a more important role in the police than support at work, or more generally, what role it plays in the context of the other social resources. Our results highlight that social resources are a complex topic that would be worthwhile to examine in more depth in further studies. In particular, the different facets should be theoretically distinguished, intercorrelations determined, and predictions for different mental health outcomes investigated. However, this does not call into question the high found importance of sense of community. It seems to be central to the mental health of police officers and should be considered in future studies and investigated in the context of other social resources.

Possibilities for development was identified as the most important organizational resource in this study. It explained an additional 2% and 4% of the variance in burnout symptoms and job satisfaction, respectively. Since organizational resources have generally been studied less frequently than social resources among police officers, there has been no comparable study of possibilities for development in the police to date. Our results suggest that variety at work and the opportunity to learn new things are important for police officers’ mental health. This finding is also consistent with the assumption of the Job Demand-Control-Support model (Karasek and Theorell 1990), which claims that not only influence, but also diversity and learning opportunities make up the dimension of control (Siegrist 2005). Similarly, influence at work and, in addition, meaning of work made only a small contribution to the prediction of both outcomes.

In summary, more research is needed on the influence of specific social and organizational resources on police officers’ mental health. A broader variety of social and organizational resources than just support and autonomy should be considered.

Two other research questions focused on the interaction effects of job demands and resources that the JD-R model describes beyond the main effects. They have been examined only in one study among police officers (Santa Maria et al. 2018). To add further evidence, the third research question addressed whether the health-promoting effect of job resources on job satisfaction is moderated by job demands. The fourth research question related to the postulated buffer effect of job resources which has already been demonstrated both in general (Bakker et al. 2005; Xanthopoulou et al. 2007) and for the police (Santa Maria et al. 2018). Based on the results of our hierarchical regression analyses, work privacy conflicts as the highest job demand and sense of community and possibilities for development as the two most influential job resources were chosen as variables for the moderation analyses.

Regarding the third research question, a significant moderation effect of work privacy conflicts was found on the relationship between sense of community at work and job satisfaction. In particular, a higher extend of conflicts between work and private life strengthened the positive relationship between sense of community and job satisfaction: A low sense of community reduced job satisfaction more in the case of a higher than a lower extend of conflicts. In the case of a high sense of community, the extend of conflicts did not make a difference in job satisfaction. Hence, police officers reporting high sense of community are more resistant to the negative impact of work privacy conflicts on job satisfaction. The relationship of possibilities for development and job satisfaction was not moderated by work privacy conflicts. Moreover, sense of community at work and possibilities for development could not buffer the influence of work privacy conflicts on burnout symptoms (research question 4). A possible explanation for the different significant interaction effects could lie in the triple-match principle (de Jonge and Dormann 2006), which proposes that moderating effects are more likely to be found when stressors, resources, and mental health outcomes are all of the same dimension (cognitive, emotional, or physical). While possibilities for development are more cognitive, sense of community and both outcomes rather belong to the emotional dimension. Conflicts between work and private life which may also relate to the emotional dimension, thus, might be less capable of influencing the impact of cognitive resources such as possibilities for development than of emotional resources such as sense of community on job satisfaction.

However, sense of community at work was not able to buffer the impact of work privacy conflicts on burnout symptoms although all three variables rather belong to the emotional dimension. It is possible that the varying degree to which they are related to work plays a role here: Sense of community at work and work privacy conflicts are both highly work-related, while burnout symptoms are a general health-related indicator which might result from working conditions but also from individual characteristics or personal issues. Nevertheless, sense of community at work had a significant main effect on burnout symptoms. Therefore, strengthening this social resource, despite everything, is a recommended strategy for reducing burnout symptoms at a workplace.

At the same time, conflicts between work and private life were the demand with significant main effects on burnout symptoms and on job satisfaction. This finding is consistent with the fact that work-family pressures are considered an important organizational stressor and negative work-related condition for police officers (Galanis et al. 2021; Violanti et al. 2017). Collins and Gibbs (2003) even identified demands of work impinging on home as the most significant organizational stressor. The studies based on the JD-R model confirmed these findings: Martinussen et al. (2007) found work-family pressures to predict all three burnout dimensions (exhaustion, cynicism, professional efficacy). Wolter et al. (2019a) showed work privacy conflicts to be negatively related to work engagement. Furthermore, van den Broeck et al. (2010) declared work-home interference and emotional demands as job hindrances and proved their joint negative effect on exhaustion and positive effect on vigor. In the present study, emotional demands were examined separately and only contributed significantly to the prediction of job satisfaction. Both, emotional demands, and work privacy conflicts are, however, difficult to reduce and even impossible to eliminate as they are inherent to daily police work. Knowledge of relevant resources and their promotion is therefore even more important for improving police officers’ mental health. As only one interaction effect was detected, it is suggested to focus on the direct effects of the job resources.

Limitations

There are some study limitations that should be addressed.

The first limitation relates to the cross-sectional study design, which does not allow for causal inferences regarding the direction of the relationship between job characteristics and mental health outcomes. However, previous studies using a longitudinal study design have empirically validated the processes postulated in the JD-R model (Hakanen et al. 2008; Schaufeli et al. 2009) supporting the main and interaction effects found in the present study.

The second limitation refers to the classification and selection of the job resources. In the present study, we differentiated job resources into social and organizational resources (Demerouti et al. 2001; Udris et al. 1992) even though other classifications exist (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Demerouti and Nachreiner 2019; Lesener et al. 2020). These further differentiate organizational resources, for example, or subdivide social resources in terms of their sources (superiors and colleagues). However, since social resources have been studied more frequently so far, we wanted to examine whether other work-related resources play a role beyond social resources. Nevertheless, in future studies, a further subdivision of organizational resources should be made to be able to assign effects to different levels of a workplace (e.g., task, organization at large). Moreover, personal resources could be considered. In the present study, they were excluded according to the authors of the original JD-R model who claimed them to be stable and unchangeable through workplace interventions (Demerouti et al. 2001). However, they have been subsequently included in the JD-R model, but systematic studies on their specific role do not yet exist (Schaufeli and Taris 2014). Furthermore, the three social and organizational resources selected can be questioned. Our concern was to include a variety of different resources from the two subcategories and to detect effects of the specific resources. The selected resources of social support (Martinussen et al. 2007; Santa Maria et al. 2018; van den Broeck et al. 2010; Wolter et al. 2019b), leadership quality (Santa Maria et al. 2019), and influence at work (Frank et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2016; Martinussen et al. 2007) have been shown to be important for the mental health of police officers. The importance of possibilities for development can be derived from the Job Demand-Control-Support model (Karasek and Theorell 1990). The resources sense of community at work and meaning of work were further chosen based on their supposed role in policing. However, it cannot be ruled out that further job resources may be relevant in the police context. Regarding the social support variable, no further differentiation between the two sources colleagues and supervisors was made for reasons of complexity. Future studies could expand the selection and include further resources from the two subcategories or differentiate social support at work as outlined above.

The third limitation relates to the selection of the outcome measures. We selected one positive and one negative outcome each to be able to display both main processes of the JD-R model. Typically, the two outcome measures are burnout and work engagement. Job satisfaction is an alternative positive mental health outcome (Gusy et al. 2020). Since job resources do not have the same effect on negative and positive outcomes and even on the positive outcomes of work engagement and job satisfaction (Gusy 2017), the results of this study cannot be applied to work engagement without exception. Instead, further research is needed regarding the effects of job resources on different positive mental health outcomes including work engagement.

Finally, the moderators and predictors of the interaction effects tested were empirically chosen. Future studies could consider the triple-match principle (de Jonge and Dormann 2006) when selecting variables for moderation analyses.

Strengths and Implications

Despite these limitations, the present study provides a comprehensive test of job resources with respect to the mental health of police officers within the theoretical framework of the JD-R model. Existing studies showed job resources, in addition to job demands, to be predictive for police officers’ mental health (Frank et al. 2017; Hu et al. 2016; Martinussen et al. 2007; Santa Maria et al. 2018; van den Broeck et al. 2010; Wolter et al. 2019b). A subdivision of social and organizational resources has rarely been undertaken in studies on the police (Hu et al. 2016) but is suggested by differential effects found in recent meta-analyses (Gusy et al. 2020; Lesener et al. 2020). Moreover, the studies did not examine all the effects described in the JD-R model, i.e., effects on positive mental health and interaction effects.

Acting on this research gap, we differentiated social and organizational resources and tested their unique and differential effects as well as interaction effects. The influence of social resources was confirmed; the additional importance of organizational resources was highlighted. In specific, sense of community at work and possibilities for development emerged as the most influential job resources. The association of sense of community at work and job satisfaction, however, was moderated by work privacy conflicts.

The study suggests further research is needed on subcategories and specific resources in order to provide evidence for further theory development as well as for resource-specific interventions in the workplace. The findings moreover suggest the further development of the JD-R model and the definition of different resource subcategories. Although influential job demands such as work privacy conflicts must not be neglected in workplace interventions, strengthening specific job resources is considered a promising approach.

Data Availability

The data was collected as part of a health survey under strict data protection guidelines in accordance with the European Data Protection Regulation. The police headquarters has not given the researchers its permission to share their data.

References

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2007) The Job Demands-Resources model: state of the art. J Manag Psychol 22(3):309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Euwema MC (2005) Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. J Occup Health Psychol 10(2):170–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170

Burr H, Berthelsen H, Moncada S, Nübling M, Dupret E, Demiral Y, Oudyk J, Kristensen TS, Llorens C, Navarro A, Lincke H-J, Bocéréan C, Sahan C, Smith P, Pohrt A (2019) The third version of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Saf Health Work 10(4):482–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2019.10.002

Collins PA, Gibbs ACC (2003) Stress in police officers: a study of the origins, prevalence and severity of stress-related symptoms within a county police force. Occup Med 53(4):256–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqg061

Crawford ER, LePine JA, Rich BL (2010) Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: a theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J Appl Psychol 95(5):834–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019364

de Jonge J, Dormann C (2006) Stressors, resources, and strain at work: a longitudinal test of the triple-match principle. J Appl Psychol 91(6):1359–1374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1359

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB (2001) The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol 86(3):499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Demerouti E, Nachreiner F (2019) Zum Arbeitsanforderungen-Arbeitsressourcen-Modell von Burnout und Arbeitsengagement – Stand der Forschung. Z Arb Wiss 73(2):119–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41449-018-0100-4

Frank J, Lambert EG, Qureshi H (2017) Examining police officer work stress using the Job Demands-Resources model. J Contemp Crim Justice 33(4):348–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986217724248

Galanis P, Fragkou D, Katsoulas TA (2021) Risk factors for stress among police officers: a systematic literature review. Work 68(4):1255–1272. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-213455

Gusy B (2017) Arbeit und Gesundheit: Eine metaanalytische Befundintegration [Habilitation]. Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.17169/REFUBIUM-10364

Gusy B, Lesener T, Wolter C (2020) Arbeitsbezogene Ressourcen und Wohlbefinden. Public Health Forum 28(2):128–131. https://doi.org/10.1515/pubhef-2020-0017

Hakanen JJ, Schaufeli WB, Ahola K (2008) The Job Demands-Resources model: a three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work Stress 22(3):224–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802379432

Hayes AF (2018) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach (Methodology in the social sciences), 2nd edn. The Guilford Press

Hu Q, Schaufeli WB, Taris TW (2016) Extending the job demands-resources model with guanxi exchange. J Manag Psychol 31(1):127–140. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-04-2013-0102

Johnson JV, Hall EM (1988) Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am J Public Health 78(10):1336–1342. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.78.10.1336

Karasek RA, Theorell T (1990) Healthy work. Stress, productivity and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books, US

Lesener T, Gusy B, Jochmann A, Wolter C (2020) The drivers of work engagement: a meta-analytic review of longitudinal evidence. Work Stress 34(3):259–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2019.1686440

Lesener T, Gusy B, Wolter C (2019) The job demands-resources model: a meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work Stress 33(1):76–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1529065

Lincke H-J, Vomstein M, Lindner A, Nolle I, Häberle N, Haug A, Nübling M (2021) COPSOQ III in Germany: validation of a standard instrument to measure psychosocial factors at work. J Occup Med Toxicol 16:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-021-00331-1

Martinussen M, Richardsen AM, Burke RJ (2007) Job demands, job resources, and burnout among police officers. J Crim Just 35(3):239–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2007.03.001

Santa Maria A, Wolter C, Gusy B, Kleiber D, Renneberg B (2019) The impact of health-oriented leadership on police officers’ physical health, burnout, depression and well-being. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 13(2):186–200. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pay067

Santa Maria A, Wörfel F, Wolter C, Gusy B, Rotter M, Stark S, Kleiber D, Renneberg B (2018) The role of job demands and job resources in the development of emotional exhaustion, depression, and anxiety among police officers. Police Q 21(1):109–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611117743957

Schaufeli WB (2017) Applying the Job Demands-Resources model. Organ Dyn 46(2):120–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.008

Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, van Rhenen W (2009) How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J Organ Behav 30(7):893–917. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.595

Schaufeli WB, Taris TW (2014) A critical review of the job demands-resources model: implications for improving work and health. In: Bauer GF, Hämmig O (eds) Bridging occupational, organizational and public health: a transdisciplinary approach, 1st edn. Springer, pp 43–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5640-3_4

Siegrist J (2005) Stress am Arbeitsplatz. In: Schwarzer R (ed) Enzyklopädie der Psychologie: Gesundheitspsychologie. Hogrefe, pp 303–318

Udris I, Kraft U, Mussmann C, Rimann M (1992) Arbeiten, gesund sein und gesund bleiben: Theoretische Überlegungen zu einem Ressourcenkonzept. Psychosozial 15(52):9–22

van den Broeck A, de Cuyper N, de Witte H, Vansteenkiste M (2010) Not all job demands are equal: differentiating job hindrances and job challenges in the Job Demands-Resources model. Eur J Work Organ Psy 19(6):735–759. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320903223839

Violanti JM, Charles LE, McCanlies E, Hartley TA, Baughman P, Andrew ME, Fekedulegn D, Ma CC, Mnatsakanova A, Burchfiel CM (2017) Police stressors and health: a state-of-the-art review. Policing 40(4):642–656. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-06-2016-0097

Wolter C, Santa Maria A, Gusy B, Lesener T, Kleiber D, Renneberg B (2019a) Social support and work engagement in police work: the mediating role of work-privacy conflict and self-efficacy. Policing Int J Police Strateg Manag 42(6):1022–1037. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-10-2018-0154

Wolter C, Santa Maria A, Wörfel F, Gusy B, Lesener T, Kleiber D, Renneberg B (2019b) Job demands, job resources, and well-being in police officers—a resource-oriented approach. J Police Crim Psychol 34(1):45–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9265-1

Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Dollard MF, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB, Taris TW, Schreurs PJ (2007) When do job demands particularly predict burnout? J Manag Psychol 22(8):766–786. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710837714

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Education Schwäbisch Gmünd and is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964.

Informed Consent

All participants were informed that participation was voluntarily and anonymous, and that all data was edited, analyzed, and represented anonymized. It is therefore not possible to draw conclusions about individuals. The data was handled in accordance with the strict requirements of data protection. Participants could discontinue the questionnaire before completion at any point of time.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The police headquarters had no further involvement with regard to study design, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing process, or submission of the article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rauschmayr, S., Schleicher, K. & Dohnke, B. Job Resources in the Police: Main and Interaction Effects of Social and Organizational Resources. J Police Crim Psych 38, 716–727 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-023-09592-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-023-09592-4