Abstract

Police officers are subjected, daily, to critical incidents and work-related stressors that negatively impact nearly every aspect of their personal and professional lives. They have resisted openly acknowledging this for fear of being labeled. This research examined the deleterious outcomes on the mental health of police officers, specifically on the correlation between years of service and change in worldviews, perception of others, and the correlation between repeated exposure to critical events and experiencing Post-Traumatic Symptoms. The Cumulative Career Traumatic Stress Questionnaire- Revised (Marshall in J Police Crim Psychol 21(1):62−71, 2006) was administered to 408 current and prior law enforcement officers across the United States. Significant correlations were found between years of service and traumatic events; traumatic events and post-traumatic stress symptoms; and traumatic events and worldview/perception of others. The findings from this study support the literature that perpetual long-term exposure to critical incidents and traumatic events, within the scope of the duties of a law enforcement officer, have negative implications that can impact both their physical and mental wellbeing. These symptoms become exacerbated when the officer perceives that receiving any type of service to address these issues would not be supported by law enforcement hierarchy and could, in fact, lead to the officer being declared unfit for duty. Finally, this research discusses early findings associated with the 2017 Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act and other proactive measures being implemented within law enforcement agencies who are actively working to remove the stigma associated with mental health in law enforcement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On December 9, 2015, Nicole Rikard, a crime scene investigator for the Asheville Police Department in North Carolina received word that her 38-year-old husband, Sergeant John Rikard, also of the Ashville Police Department, had been found dead in their home of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound (Balaban and Doubek 2019). In October 2017, Sergeant Michael Borland, a 44-year-old sergeant who spent 21 years with the Pinellas County Sheriff’s Office, was found deceased in the parking lot of the St. Petersburg College-Veterinary Technology Center, also from a self-inflicted gunshot wound (Pinellas Co. Sheriff’s Office press release 2017). Shortly after 6 pm on August 14, 2019, veteran NYPD officer, Robert Echeverria, died at his home from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Officer Echeverria was only 56 years old and the ninth NYPD officer to commit suicide in 2019 following a fellow NYPD officer who killed himself the previous day (Moore and Celona 2019).

Law enforcement officers have historically been required to perform many functions within the scope of their jobs. They protect and serve the public, which at times requires them to assume the role of social worker, guidance counselor, and impartial peacekeeper. These roles, however, come with an emotional price tag. They are front-row witnesses to horrific atrocities including catastrophic natural disasters, acts of terrorism that results in mass casualties, suicides, motor vehicle accidents that result in trauma and/or death, child abuse or neglect, and acts of domestic violence.

These cumulative traumatic events have the potential to impact the individual and result in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as defined by the American Psychiatric Association. A study by Stephens and Long (1999) noted that between 12 and 35% of police officers suffered from PTSD. Another, examining the impact of suicide exposure on law enforcement found that nearly all their study participants (95%) indicated they had been exposed to an average of 30 career suicide scenes with two occurring over the 12 months prior to the study (Cerel et al. 2019). Additionally, it was noted that over 20% of those who responded indicated they experienced difficulties after the exposure including nightmares. After years of research, planning, and debate, the most recent version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the DSM-5, revised how PTSD was defined. It was removed from the anxiety disorder category, in part, because of the multiple emotions associated with PTSD (i.e., guilt, shame, and anger). It was subsequently placed in a new category, appropriately named “Trauma and Stressor-related Disorders”. This diagnostic category is distinctive among psychiatric disorders in the requirement of exposure to a stressful event as a “precondition” (Pai et al. 2017 p. 2.). This is significant and relevant to law enforcement because it encapsulates the symptoms they experience, often daily, over the course of their career.

It was decades after American troops returned from Vietnam that the mental health community openly acknowledged that soldiers deployed into war zones were emotionally traumatized by what they had witnessed and been exposed to. Regrettably, Vietnam veterans with PTSD symptomology did not receive proper mental health services upon their return. It was not until 1980 that the diagnosis of PTSD made its first appearance in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-lll) published by the American Psychiatric Association. Similarly, in the quasi-military world of policing, officers too often find themselves exposed to traumatic events, but fear of being labeled as “not tough enough for the job”, “weak”, or even declared to be “unfit for duty” makes it difficult for them to display emotion and admit to experiencing stress in order to safeguard their career (Bonifacio 1991; Brown et al. 1994).

Research indicates that police officers suffer from higher-than-average instances of substance abuse and suicide when compared to the general population (Barron 2010; Cross and Ashley 2004; O’Hara et al. 2013). While the overall suicide rate in the USA is 13 per 100,000, the number for law enforcement is closer to 17 for every 100,000 (Hillard 2019). Between January 2016 and December 2019, there were over 700 reported current or former law enforcement officer deaths by suicide (www.bluehelp.org). In fact, it was noted that a law enforcement officer was more likely to die by suicide than to be killed in the line of duty (www.bluehelp.org). This work presents a summary of the literature on the most prevalent police stressors, the impact these stressors have on an officer’s physical and emotional well-being, and strategies for assistance. It further provides the findings of a descriptive, cross-sectional, and quantitative study, conducted by the authors, that examined how the variables of tenure (years of service), exposure to traumatic events, and gender and race of officer are associated with post-traumatic stress symptoms and change in officer’s worldview and perception of others.

Literature Review

Impact of Long-Term Exposure

There are copious amounts of research supporting the deleterious effects of police stress (Cerel et al. 2019; Chopko et al. 2018; Morash et al. 2006; Soomro and Yanos 2018; Stinchcomb 2004). Many of these studies focus on stress arising from one of two areas related to policing: operational stressors that would include stress from the demands and duties of the occupation and organizational stressors that include things such as a perceived lack of support, pressure from administration or a lack of opportunities to move up the hierarchy (Shane 2010; Stinchcomb 2004; Violanti 2011). Symptoms of long-term traumatic stress exposure, according to Marshall (2006), may appear without warning, leaving an officer confused and unprepared to cope. There is additional research, however, that focuses on the impact of law enforcement officers who have experienced mass casualty situations, did not feel comfortable seeking out any type of meaningful long-term mental health services, due to potential stigmas, and then returned to police work (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2018). The image that comes to mind is of a juggler attempting to maintain multiple fire sticks and having a double-edge sword thrown in when they were unprepared.

Witt (2005), speaking of decorated Oklahoma police officer turned convicted drug felon Jim Ramsey, summed it up best by saying:

There’s a dark underside to the heroics performed by rescue workers that is little noticed by citizens they protect: Long after the smoke clears and the last bodies are retrieved, massive disasters and terrorist attacks routinely claim additional casualties among the first responders who rush in to help, only to succumb to alcoholism, broken families and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). (n.p.)

Following the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center, Lowell et al. (2017) examined longitudinal studies of PTSD among those most exposed populations between October 2001 and May 2016. The findings suggested a significant burden of 9/11-related PTSD among those most exposed, and while most studies they examined indicated a decline in rates of the prevalence of PTSD, those of rescue/recovery workers showed an increase over time. Many of those serving in the capacity of rescue/recovery at both the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building and the twin towers of the World Trade Center were police officers and other first responders. Telesco (2019) noted that the WTC Health Registry, who followed up on individuals directly impacted by the events of 9/11 including police officers, found an “elevated prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and physical and mental health burdens among 9/11-exposed individual’s years after exposure” (p. 10). Many of the police officers, who were physically able, went back out on the streets and to the daily stressors of being a police officer that were compounded by what they had been exposed to at ground zero.

There has been a steady stream of research conducted, over the past several decades, pertaining to the psychological impact of critical incidents on law enforcement officers. Spielberger et al. (1981a, b) were early pioneers in this area focused their research specifically on areas including salary, shift work, administrative hierarchy, and job-related conflicts, as well as crises that occurred within the scope of their job were all examined.

Sheehan and Van Hasselt (2003) noted that “among law enforcement officers, job-related stress frequently contributes to the ultimate maladaptive response to stress: suicide” (p.16). Police organizations are beginning to acknowledge that they are now facing a mental health crisis of epic proportion and to combat this crisis a fundamental change in the police culture must occur. This change involves implementing proactive and ongoing mental healthcare practices with a focus on addressing the psychological equilibrium of law enforcement officers.

Similar findings were noted by Mumford et al. (2021), whose study focused on the physical and mental health of law enforcement officers as well as Price (2017), who acknowledged there had been an increase in wellness programs whose goal is to mitigate the effects of job-related stress. Finally, Price (2017) also reiterates previous findings that job-related stressors and/or exposure to critical incidents have a greater likelihood to manifest into symptoms including PTSD-like symptoms, increased alcohol abuse, increased suicide risk, relationship problems, depression, and aggressive conduct.

Law enforcement officers are subjected to not only critical incidents that occur within the day-to-day function of the job, but are also subject to other, more subtle, factors including organizational stressors (i.e., inadequate training, poor supervision, perceived inequality); additional job stressors (i.e., long hours in addition to “on call” status); public scrutiny; and specialized duties (i.e., undercover assignments, hostage rescue, or crisis negotiation). This is compounded by the normal personal problems that can occur including the physical changes that occur in our bodies as we begin to get older; increased likelihood of injury or illness; or psychological factors (Sheehan and Van Hasselt 2003; Wagner et al. 2020). These researchers noted that it was not a situation where either critical incidents or cumulative stressors alone would cause law enforcement officers undue stress, but rather the convergence of these factors.

Several studies have confirmed a relationship between the frequency by which law enforcement officers were exposed to critical incidents and PTSD symptom variables (Weiss et al. 2010; Chopko et al. 2015; Geronazzo-Alman et al. 2017). The instrument used for this study is the Cumulative Career Traumatic Stress Survey or CCTS. Marshall (2006) developed the CCTS based on both her experience as a law enforcement officer and as a trauma therapist. Like assertions made by Weiss et al. (2010) and Van Hasselt et al. (2008), Marshall (2006) noted that symptoms of CCTS were like PTSD with the exception that PTSD typically resulted from a single or sudden traumatic event. The impact of the event can result in the slow and subtle deterioration of the officer’s emotional and psychological stability that is more trauma than stress based. This slow deterioration can manifest in the form of intrusive thoughts, flashbacks or nightmares, anxiety, hyperarousal, sleeping and/or eating problems, disconnection from family and/or friends, emotional numbing, and moodiness. They can negatively impact the officer both personally and professionally in the form of impaired job performance, diminished physical health, or marital/family problems (Geronazzo-Alman et al. 2017; Marshall 2006; Van Hasselt et al. 2008). These align with the findings of previous research that focused on symptomology. An additional finding of interest made by Marshall (2006) was the change in worldview experienced since becoming a law enforcement officer. This included a change in the perception of others, a lack of trust of others, being prejudice towards others, and experiencing a change in faith/beliefs.

Tucker (2015) noted there appeared to be a gap in the literature that explores the value of organizational support, specifically in stress intervention services. She examined the likelihood of law enforcement officers voluntarily utilizing stress intervention services and found that if officers perceived their organization to be in support of these services, they would be more likely to utilize them. Conversely, if there was the perception of an officer being stigmatized using these services, there was a significant decline in their willingness to do so.

Changing an Ingrained Culture

The federal government has taken steps to ensure the mental health crisis within law enforcement organizations is addressed via the Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act of 2017 (2017). The philosophy underlying the policy is to assess whether law enforcement agencies have implemented mental health and wellness programming and determine what impact the implementation of those services has had on their officers and organizations. It incorporates a holistic approach to police officers, staff, and their family’s mental health and wellness after research indicated a direct correlation between the occupation and higher rates of chronic physical illnesses, domestic incidents, substance abuse, and mental health disorders including depression, anxiety, and PTSD. The final report was presented to Congress in early 2019 by Spence et al. (2019) and included information related to services and resources available to military veterans and law enforcement officers.

That same year, Copple et al. (2019) submitted a report to the DOJ that provided an overview of several successful and promising law enforcement mental health and wellness strategies that had been implemented in a diverse group of police agencies across the country including agencies creating a sense of ownership and support for the programs from the top police administrative officials down. In addition, the report included a summary of the peer crisis response hotline (Cop2Cop) including the design elements of a hotline and the necessary follow-up care and support provided by well-trained officers communicating with other officers. The report acknowledged that many police agencies have, in place, employee assistance programs (EAP) that are sponsored by the local government where they are located.

Based on the literature, there is a critical need to develop more comprehensive services for police officers exposed to traumatic events and police stress and implement early prevention assessment along with mental health and wellness strategies that are proactive rather than reactive. The current study examines the relationship between years of service, traumatic events, and deleterious outcomes of post-traumatic symptoms and change in perception of world and others. The authors also explored whether these outcomes are different among demographic factors.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Research Questions Related to the Independent Variable = Tenure/Years of Service

-

RQ # 1: Is officer tenure (years of service) associated with reported traumatic events?

-

HR # 1: Officer tenure (years of service) is associated with reported traumatic events.

-

RQ # 2: Is officer tenure (years of service) associated with reported post-traumatic symptom (PTS) outcomes?

-

HR # 2: Officer tenure (years of service) is associated with reported post-traumatic symptom (PTS) outcomes.

-

RQ # 3: Is officer tenure (years of service) associated with reported changes in perception of world and others?

-

HR # 3: Officer tenure (years of service) is associated with reported changes in perception of world and others.

Research Questions Related to the Independent Variable = Traumatic Events

-

RQ # 4: Are traumatic events associated with reported post-traumatic symptoms (PTS) outcomes?

-

HR # 4: Traumatic events are associated with reported post-traumatic symptoms (PTS) outcomes.

-

RQ # 5 Are traumatic events associated with reported changes in perception of world and others?

-

HR # 5: Traumatic events are associated with reported changes in perception of world and others.

Research Questions Related to Independent Variable = Race/Gender

-

RQ # 6: Is there a difference in reported traumatic events or psychological/behavioral outcomes on demographic characteristics of gender and race?

-

HR # 6: There is a difference in reported traumatic events or psychological/behavioral outcomes on demographic characteristics of gender and race?

Procedures

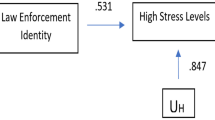

An IRB approved, cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted utilizing a convenience sample of law enforcement officers yielding a total of 408 respondents (n = 408). To address the research questions, the Cumulative Career Traumatic Stress Questionnaire-CCTS-R (Marshall 2006) was administered (Fig. 1). The CCTS-R is a 60-item instrument and includes items measuring their opinion of others; their trust of others; their prejudice towards others; and whether they had experienced a change in faith or religious beliefs, job-related traumatic events, PTSD-like symptoms or experiencing personal/behavioral changes, and whether there was a history of anxiety/depression prior to becoming a sworn law enforcement officer. The instrument is broken down into 4 sections; part I asks respondents to self-report on demographic information (race, gender, rank, years of service, etc.); part II represents 20 items related to traumatic events as respondents to self-report with Yes/No whether they have experienced any of the items since being on the job. Some of the items include Have you confronted a person with a gun? Have you been involved in a shooting? Has a co-worker been shot or killed while on-duty? Have you responded to an incident involving the death of a child? Respondent’s scores can range from 20 to 40 (40 representing the highest reporting of traumatic events).

Part III represents 15 items related to post-traumatic stress symptoms, and part IV represents 11 items specific to change in perception of the world and others and contains Likert type responses. Examples of the items include Since being on the job…. I have experienced nightmares as a result of an incident, I have experienced flashbacks of an incident, I experience recurring memories of an event after being reminded by another event, I re-experience physical reactions of an event after being reminded by another event. The lowest possible self-reported post-traumatic stress symptom being a score of 15 and the highest score being 60.

Lastly, the world view and perception of others section represents 11 items that asks respondents to self-report on whether their perception of the world or others has changed since being on the job. Some examples include My opinion of other people has changed, I no longer trust others. Stress from the job has affected my relationship with family members. These scores range from 11 to 44 with 44 indicating the highest change in perception of the world and others.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The sample population of 408 respondents represented 83% male and 17% female. Over 81% (n = 332) identified as being Caucasian; about 5% (n = 23) identified as being African American; and 6% (n = 26) identified as being Hispanic American. There were significantly lower numbers of those who identified as Asian American (2%) and Native American less than 1%. Close to 3% reported “Other”.

In terms of education and rank, 53% of the sample indicated they held either an associate or baccalaureate degree, and nearly 30% indicated having some college. About 7% of the sample reported “no college” at all. For the variable “Rank”, 35% identified their rank as “Police Officer or Police officer /Trooper 1st Class”, while the rank of “Sergeant and Corporal” accounted for about 29% of the sample. Over 26% reported their rank as lieutenant or above and 10% identified their rank as “other”. While the average number of years reported was 4 years, close to 28% reported having 26 + years.

For the items representing traumatic events, the findings indicated that most officers in the sample had experienced a major traumatic event in their career with close to 92% of the sample reporting that they had confronted a person possessing a gun. Ninety eight percent of the sample indicated that they had confronted a person possessing a weapon other than a firearm and having to use force other than deadly force. The most disturbing call that officers identified was a child abuse/neglect or death of a child complaint. Eighty six percent reported a child abuse/neglect complaint and 73% involving the death of a child. One of the items that is most interesting and consistent with the literature is that 35% of the sample reported that they had a co-worker who committed suicide and 7% of the sample reported that they “sometimes think of suicide” (Hackett and Violante 2003; O'Hara et al. 2013).

One finding that is inconsistent with the literature is that 42% of the sample reported never using alcohol to relax and less than 10% report never using alcohol. According to the Substance Abuse & Mental Health Data Archive (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2019), among the 139.7 million current alcohol users aged 12 or older in 2019 in the USA, 65.8 million people (47.1%) were past month binge drinkers. The literature on police alcohol use indicates a much higher prevalence than reported in this sample (Ménard and Arter 2013; Chopko et al. 2013).

Among the Change in WorldView and Perception of Others items, the findings showed that close to 40% of the sample no longer trusts others and feels that the world is an unsafe place. Consistent with the literature on police and their family relationships, 36% of the sample reported that the stress from the job has affected their relationship with family members (Karaffa et al. 2015). Interestingly 43% of the sample report never having lost faith in religious beliefs. This finding indicates that future research on faith as a coping strategy is worth investigating.

The post-traumatic stress items show that close to 40% of the sample have experienced nightmares as a result of an incident or incidents, had flashbacks of an incident, or experienced recurring memories. A small minority of the sample (14%) reported having no trouble sleeping. Close to 44% of the sample reported that they have difficulty concentrating and experience jumpiness or restlessness. All of these descriptive findings are consistent with the literature on stress symptoms in police (Marshall 2006).

Scales Internal Consistency

A reliability analysis was run on the three subscales of the cumulative career traumatic stress measurement. Part II of the instrument represented “Traumatic Events” items, part II I represented “Post Traumatic Symptoms” items, and part IIV represented “Perception of World/Others” items. For part II traumatic events, the findings indicate a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of α = 0.71 (Table 1). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for post-traumatic symptoms was reported as α = 0.91 (Table 2) and worldview/perception of others α = 0.85 (Table 3).

Inferential Statistics

Tenure/Years of Service and Traumatic Event, PTS, and World View/Perception of Others

-

HR # 1: Officer tenure (years of service) is associated with reported traumatic events.

-

HR # 2: Officer tenure (years of service) is associated with reported post-traumatic symptom (PTS) outcomes.

-

HR # 3: Officer tenure (years of service) is associated with reported changes in perception of world and others.

To test hypotheses HR # 1, a Spearman’s correlation was run to assess whether there was a relationship between years of service in law enforcement and traumatic events, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and worldview and perception of others. Table 1 illustrates that years of service was significantly correlated with traumatic events (0.471) supporting hypothesis # 1. HR # 2 and HR # 3 were not supported by the analysis (Table 4).

Traumatic Events and PTS Symptoms/WorldView Perception of Others

-

HR # 4: Traumatic events are associated with reported post-traumatic symptoms (PTS) outcomes.

-

HR # 5: Traumatic events are associated with reported changes in perception of world and others.

To test hypotheses HR #4 and 5, a Spearman’s correlation was run to assess whether there was a relationship between Traumatic Events and PTS symptoms. Table 5 indicates a significant association at 0.383. Traumatic events and worldview/perception of others were significantly correlated at 0.272 (Table 6). HR # 6 was not supported.

Traumatic Event, PTS, WorldView, and Race/Gender

-

HR # 6: There is a difference for traumatic events, PTS symptoms, and worldview on the demographic variables of gender and race.

An independent t-test and ANOVA were run to determine whether there were differences among gender and race on the independent variables. These hypotheses were not supported showing no significant differences.

Discussion

The findings from this study support the literature that perpetual long-term exposure to critical incidents and traumatic events, within the scope of the duties of a law enforcement officer, has negative implication that can impact both their physical and mental well-being. These symptoms become exacerbated when the officer perceives that receiving any type of service to address these issues would not be supported by law enforcement hierarchy and could, in fact, lead to the officer being declared unfit for duty. The symptoms may be in the form of increased physical ailments, including increased instances of injuries sustained on the job and increased stress-related diagnoses including gastrointestinal ulcers or hypertension. It could also manifest in the form of a significant personality or behavioral change including an officer being quicker to get into a physical altercation with a citizen, increased instances of domestic altercations, increased instances of alcohol and/or prescription drug abuse, noted depression, or suicide. Of interest was that this study did not indicate a correlation between years of service and increased alcohol abuse or between years of service, and a loss of faith and/or religious beliefs yet did indicate an overall loss of faith in the goodness and trustworthiness of people. These specific variables warrant further research to determine if the lack of reported alcohol abuse was simply underreported by this sample or if it indicates something altogether different, for example, the beginning of a change in police culture that no longer stigmatizes officers who seek help after experiencing a traumatic event. Additionally, what role does an individual’s faith or religious beliefs play in their ability to cope with the stressors of the job of being a law enforcement officer? Did they have faith to begin with? If so, was that faith the catalyst that allowed them to persevere during their darkest times on the job? Cox et al. (2019) indicated that law enforcement officers may, as a survival mechanism, become more cynical, yet the results from this study indicated no significant correlation existed. Additionally, this research did not include an exploration of size and location of the department or type of traumatic event. These variables are worthy of examination for future research as they may either modify or confound the outcome variable.

Implications

Dawson (2019) notes, “The ‘bulletproof cop’ does not exist. The officers who protect us must also be protected against incapacitating physical, mental and emotional health problems, as well as against the hazards of their jobs” (n.p.). This work contributes to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence to support the need for law enforcement administrators and systems to take a more proactive approach in addressing the mental health and well-being of law enforcement officers. The 2017 Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act and other subsequent studies provide evidence demonstrating that police agencies who have implemented holistic proactive approaches to officer’s mental health report a decline in the negative impacts of job-related stressors. In an attempt to encourage more of these cultural changes and reduce stigmas associated with police mental health, there are federal grant opportunities for law enforcement agencies to take advantage of to help fund programming. These grants can offer police agencies an opportunity to implement critical infrastructure changes as well as important and evidenced based mental health programming. Investing in our police and their mental and physical well-being may help reduce instances of alcohol abuse, relationship conflict, suicidal ideation, negative perception of others, abuse of authority and excessive force complaints, and officer turnover.

Law enforcement agencies with proactive approaches to mental health report that these efforts lead to recruiting stronger candidates. A mental health paradigm shift from stigma to support can help officers learn strategies to cope with police stressors and traumatic events in a healthy way. The importance of all stakeholders, politicians, police administrators, police unions, and the rank-in file officers themselves, need to “buy-in” to this paradigm shift as a collaborative effort between law enforcement and mental health professionals to help heal our police officers is crucial.

As with any new relationship, and especially in the police culture where suspicion and doubt have become second nature, there needs to be adequate time for trust and a bond to form so that officers feel they can openly and honestly discuss without fear of administrative reprisals. This relationship should ideally begin during the cadet phase and be encouraged to continue throughout the officer’s career. The results of this current study demonstrate that the longer the officer is on the job, the more likely they are to experience traumatic events, thus leading to deleterious mental health outcomes. Therefore, the open lines of trust and communication must be present throughout the officer’s entire tenure with the department.

Critical incidents and job stressors are an unfortunate part of being a law enforcement officer. The key to success, however, is openly acknowledging them, removing the long-standing stigma, having open and honest discussions, and learning strategies of coping with them. Further studies on police stress and mental health outcomes are necessary to be explored in large and small departments as well as rural and urban police agencies. Law enforcement agencies spend millions of dollars each year in training and equipment for officers to ensure their protection and safety. Implementing holistic proactive approaches to that same officer’s mental health and well-being should be treated as an additional piece of equipment they carry with them that allows them to be more effective in their respective roles of protecting and serving the public.

Recommendations for Intervention Strategies

As mentioned earlier, this population is unique in the willingness to seek psychological assistance and support in the first place. Officer perceptions of stigma can be considered an enormous barrier to treatment (Milot 2019). Police departments can provide stronger support for their officers by seeking to employ evidenced based and trauma informed assistance. The impact that policing has on an officer’s “worldview” and the ability to navigate the bombardment of traumatic exposure is the challenge for law enforcement executives. Officers are immersed in the experience of interacting with people when they are at their worst. These officers have a front row seat to human suffering. This trauma informed compassion fatigue, burnout, cynicism, and other deleterious psychological outcomes should be a wake-up call to policymakers. Early intervention methods, counseling and psychological services, and peer support are among the common intervention strategies. Stigma and fear of job security are among the reasons that officers are not engaging in these strategies. An officer who is experiencing the impact that traumatic events have on psychological well-being and overall mental health reluctant to come to the supervisor with an honest appraisal of their psychological well-being for fear of having their guns taken away from them and being placed on desk duty. Police executives and policymakers need to investigate intervention strategies that align with the officer’s comfort zone.

There are evidence-based officer mental health and wellness policies and programs that afford officers the proper treatment needed for depression, anxiety, alcohol and prescription medication abuse, and post-traumatic stress syndrome. At the policymaking level, police departments could implement a broad continuum of officer mental health and wellness policies and programs. These strategies include providing officers with access to information on mental health resources, annual mental health wellness checks, in-service stress management awareness training, peer support initiatives, and psychological services (McManus and Argueta 2019). Until police executives, administrators, policymakers, legislators, and others in authority are willing to spend the resources, personnel, time, and energy in improving mental health services for police officers, we will continue to see the deleterious impact that trauma and critical event exposure have on these men and women in blue.

Availability of Data and Material

SPSS data electronically stored and available.

References

Balaban S, Doubek J (2019) After husbands' suicides, 'best widow friends' want police officers to reach for help. NPR.org. https://www.npr.org/2019/06/09/724283309/after-husbands-suicides-best-widow-friends-want-police-officers-to-reach-for-hel. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Barron S (2010) Police officer suicide within the New South Wales police force from 1999 to 2008. Police Pract Res 11(4):371–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2010.496568

Blue H.E.L.P (n.d.) https://www.bluehelp.org. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Bonifacio P (1991) The psychological effect of police work. Plenum Press

Brown JM, Wormald J, Campbell EA (1994) Stress and policing: Sources and strategies. John Wiley & Son

Chopko B, Palmieri P, Adams R (2013) Associations between police stress and alcohol use: Implications for practice. J Loss Trauma 18(5):482–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2012.719340

Cerel J, Jones B, Brown M, Weisenhorn D, Patel K (2019) Suicide exposure in law enforcement officers. Suicide Life Threat Behav 49(5):1281–1289

Chopko B, Palmieri P, Adams R (2015) Critical incident history questionnaire replication: frequency and severity of trauma exposure among officers from small and midsize police agencies. J Trauma Stress 28(2):157–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21996

Chopko B, Palmieri P, Adams R (2018) Relationships among traumatic experiences, PTSD, and posttraumatic growth for police officers: a path analysis. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy 10(2):183–189

Copple C, Copple J, Drake J, Joyce N, Robinson M, Smoot S, Stephens D, Villaseñor R (2019) Law enforcement mental health and wellness programs: eleven case studies (371). Department of Justice. https://cops.usdoj.gov/RIC/Publications/cops-p370-pub.pdf. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Cox S, Massey D, Koski C, Fitch B (2019) Introduction to Policing. 4th ed., Sage Publications. Washington, D. C

Cross C, Ashley L (2004) Police trauma and addiction: coping with the dangers of the job. PsycEXTRA Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/e311382005-006

Dawson J (2019) Fighting stress in the law enforcement community. Natl Inst Justice J. https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/fighting-stress-law-enforcement-community. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Geronazzo-Alman L, Eisenberg R, Shen S, Duarte C, Musa G, Wicks J, Fan B, Doan T, Guffanti G, Bresnahan M, Hoven C (2017) Cumulative exposure to work-related traumatic events and current post-traumatic stress disorder in New York city’s first responders. Compr Psychiatry 74:134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.12.003

Hackett D, Violante J (2003) Police suicide: tactics for prevention. Springfield, IL: C. C. Thomas

Hillard J (2019) New study shows police at highest risk for suicide than any profession. Addiction Center. https://www.addictioncenter.com/news/2019/09/police-at-highest-risk-for-suicide-than-any-profession/. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Karaffa K, Openshaw L, Koch J, Clark H, Harr C, Stewart C (2015) Perceived impact of police work on marital relationships. Fam J 23(2):120–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480714564381

Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act. U.S.C. S.867 (2017) https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/867. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Lowell A, Suarez-Jimenez B, Helpman L, Zhu X, Durosky A, Hilburn A, Schneier F, Gross R, Neria Y (2017) 9/11-related PTSD among highly exposed populations: a systematic review 15 years after the attack. Psychol Med 48(4):537–553. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291717002033

Marshall E (2006) Cumulative career traumatic stress (CCTS): a pilot study of traumatic stress in law enforcement. J Police Crim Psychol 21(1):62–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02849503

McManus HD, Argueta J Jr (2019) Officer wellness programs: research evidence and a call to action. Police Chief 86(10):16. Retrieved from https://ezproxylocal.library.nova.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/officer-wellness-programs-research-evidence-call/docview/2307719208/se-2?accountid=6579. Accessed 22 Oct 2021

Ménard K, Arter M (2013) Police officer alcohol use and trauma symptoms: associations with critical incidents, coping, and social stressors. Int J Stress Manag 20(1):37–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031434

Milot M (2019) Stigma as a barrier to the use of employee assistance programs. A Workreach Solutions research report

Moore T, Celona L (2019) Off-duty veteran NYPD cop commits suicide, ninth this year. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2019/08/14/off-duty-veteran-nypd-cop-shoots-himself-in-the-head-in-queens/. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Morash M, Haarr R, Kwat D (2006) Multilevel influences on police stress. J Contemp Crim Justice 22(1):26–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986205285055

Mumford E, Liu W, Taylor B (2021) Profiles of U.S. law enforcement officers’ physical, psychological, and behavioral health: results from a nationally representative survey of officers. Police Q. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611121991111

O’Hara A, Violanti J, Levenson R, Clark R (2013) National police suicide estimates: web surveillance study III. Int J Emerg Ment Health and Human Resilience 15(1):31–38

Pai A, Suris A, North C (2017) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the DSM-5: controversy, change, and conceptual considerations. Behav Sci 7(4):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7010007

Pinellas County Sheriff's office (2017) 17–238 off-duty sergeant dies of self-inflicted gunshot wound in Largo -. Pinellas County Sheriff's Office. https://pcsoweb.com/17-238-off-duty-sergeant-dies-of-self-inflicted-gunshot-wound-in-largo. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Price M (2017) Psychiatric disability in law enforcement. Behav Sci Law 35:113–123

Shane J (2010) Organizational stressors and police performance. J Crim Just 38:807–818

Sheehan DD, Van Hasselt VB (2003) Identifying law enforcement stress reactions early. PsycEXTRA Dataset, 12-17.https://doi.org/10.1037/e314622004-002

Soomro S, Yanos P (2018) Predictors of mental health stigma among police officers: the role of trauma and PTSD. J Police Crim Psychol 34:175–183

Spence DL, Fox M, Moore GC, Estill S, Comrie N (2019) Law enforcement mental health & wellness act: report to congress. Department of Justice. https://cops.usdoj.gov/RIC/Publications/cops-p370-pub.pdf. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Spielberger CD, Westberry LG, Grier KS, Greenvield G (1981a) Police stress survey: sources of stress in law enforcement. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/80993NCJRS.pdf. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Spielberger CD, Westberry LG, Grier KS, Greenvield G (1981b) Police stress survey (PSS). Statistics Solutions. https://www.statisticssolutions.com/police-stress-survey-pss/. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Stephens C, Long N (1999) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the New Zealand police: the moderating role of social support following traumatic stress. Anxiety Stress Coping 13(3):247–265

Stinchcomb JB (2004) Searching for stress in all the wrong places: combating chronic organizational stressors in policing. Police Pract Res 5(3):259–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/156142604200227594

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive (2018) Disaster technical assistance center supplemental research bulletin: first responders: behavioral health concerns, Emergency response, and trama. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/dtac/supplementalresearchbulletin-firstresponders-may2018.pdf. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive (2019) National Survey of Drug Use and Health 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2019-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Telesco GA (2019) Never forget, sometimes forgotten, often haunted. Journal of the American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress, Fall Issue

Tucker JM (2015) Police officer willingness to use stress intervention services: the role of perceived organizational support (POS), confidentiality and stigma. OMICS 17(1):304–314

Van Hasselt VB, Sheehan DC, Malcolm AS, Sellers AH, Baker MT, Couwels J (2008) The law enforcement officer stress survey (LEOSS). Behav Modif 32(1):133–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507308571

Violanti JM (2011) Police organizational stress: the impact of negative discipline. Int J Emerg Ment Health 13(1):31–36

Wagner S, White N, Fyfe T, Matthews L, Randall C, Regehr C, White M, Alden L, Buys N, Carey M, Corneil W, Fraess- Phillips A, Krutop E, Fleishmann M (2020) Systematic review of post traumatic stress disorder in police officers following routine work-related critical incident exposure. Am J Ind Med 63:600–615

Weiss D, Brunet A, Best S, Metzler T, Liberman A, Pole N, Fagan J, Marmar C (2010) Frequency and severity approaches to indexing exposure to trauma: the critical incident history questionnaire for police officers. J Trauma Stress 23(6):734–743. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20576

Witt H (2005) Jim Ramsey: tragedy haunts the heroes. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/careers/chi-0504180178apr18-story.html. Accessed 30 Jul 2020

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest/Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Craddock, T.B., Telesco, G. Police Stress and Deleterious Outcomes: Efforts Towards Improving Police Mental Health. J Police Crim Psych 37, 173–182 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-021-09488-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-021-09488-1