Abstract

When a child goes missing, it is commonplace to release details of the child in the hope that a member of the public can help to locate him or her. Despite their importance and daily usage, there remains a significant gap in understanding just how effective these appeals are in helping to locate missing children. This exploratory study utilized a two-stage approach and sought (1) to explore whether the length of the description and the type of content enclosed in the description influenced subsequent recall abilities, (2) to determine whether the length of time spent reading the mock appeal influences the subsequent recall ability, (3) to establish whether confidence in own recall ability is associated with overall recall ability, and (4) to determine whether descriptive length and content influences the subsequent recall ability following a 3-day break. Two hundred and twenty-three participants observed one of four mock missing children descriptions followed by a short word memory distraction task and a free-recall task. The second stage comprised of another free-recall task presented after a short 3-day delay. Two-way factorial ANOVAs found observing shorter descriptions have significantly greater recall accuracy than observing longer descriptions both immediately after observing the appeal and after a 3-day delay. Results also found that newsworthy descriptive content had a greater recall accuracy than non-newsworthy descriptive content after a 3-day delay. Additional analyses found that confidence in own accuracy and time spent observing the appeals was also significantly associated with recall accuracy. The findings demonstrate the necessity for improving missing children appeals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There are approximately 340,000 missing person incidents created in the UK each year. This is an equivalent to one report every 90 seconds (Missing People 2018; National Crime Agency [NCA] 2017). Of these reports, 60% relate to missing children. Although, this could remain a significant under representation of the true scale of missing children reports (Hayden and Shalev-Greene 2016; Hill et al. 2016; Kiepal et al. 2012; NCA 2017; Shalev-Greene et al. 2009; Smeaton and Rees 2004). Whilst the majority of missing children are located within 48 hours, a small minority will remain missing for a greater duration (NCA 2017). When a child goes missing, it is common practice for the police, charities, families, and friends to release details of the missing child in hope that members of the public can assist in locating the child faster, prior to the child experiencing any harm (Lampinen et al. 2012; Sweeney and Lampinen 2012). Despite its usage across the world, and its importance in helping to locate missing children, the literature exploring its effectiveness is underdeveloped (Drivsholm et al. 2017; Lampinen and Moore 2016; Lampinen and Sweeney 2014). This exploratory study thus sought to build on our limited understanding of appeal effectiveness by exploring some of the factors associated with descriptions of missing children on the recall ability of members of the public.

The use of the media to help distribute appeals of missing children is far from novel. Appeals have been published across numerous offline and online systems that include the use of posters, milk cartons, social media sites, radio and television broadcasts, websites, billboards, newspapers, and rescue alerts, to name a few (Drivsholm et al. 2017). Publishing missing children appeals through the media is a vital resource for law enforcement due to the ability to request help from members of the public across an extensive area in a short period of time (Fyfe et al. 2014; Taylor et al. 2013). Moreover, the use of the media allows individuals who may not hold any information about the missing child to assist by sharing the appeal with their own media followers. This re-sharing of appeals will therefore further increase the number of people that the appeal could reach (Drivsholm et al. 2017). This effect can be evidenced by the National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children ([NCMEC] 2015) who had appealed for information from members of the public following the discovery of an abandoned missing child. Within a short period of time, the appeal had been viewed over 50 million times which would have been highly unlikely to replicate using non-media sources (NCMEC 2015).

Newsworthiness

Despite the variety of methods associated with distributing appeals of missing children, limited research is available and has generally found differences between missing children who are provided with media attention and missing children who are not provided with media attention (Gilchrist 2010; Min and Feaster 2010; Moscowitz and Duvall 2011; Newiss 2005; Simmons and Woods 2015; Sommers 2017; Taylor et al. 2013). Newsworthiness is a concept frequently utilised within journalism-based research and everyday journalistic practice relating to the level of attention an event will receive within the media (Trilling et al. 2017). Excluding time-related and exclusivity factors associated with news items, journalists are found to evaluate the events against several news values to determine whether an event is newsworthy or non-newsworthy. The proximity of the event, the prominence of the individuals involved, how unusual or shocking the event is, the potential impact of the event on the readers in relation to interest, and the predicted emotional response to the event are just some of the examples of news values that drive this evaluation (Araujo and van der Meer 2018; Galtung and Ruge 1965).

Theoretically, newsworthiness can be explored through two primary theories. First, the rarity theory suggests that newsworthiness derives from the inclusion of ideal victims such as females and children, events that are unusual or dramatic, or involve more than one potential victim (Gekoski et al. 2012; Gruenewald et al. 2013; Johnstone et al. 1994; Lundman 2003; Peelo, 2006). In contrast, devaluation theory suggests that newsworthiness content derives from the pre-existing perceptions regarding the fear and vulnerability of the perceived victims which are held by the reader (Gruenewald et al. 2013; Lundman 2003). In relation to missing children, perceived stranger abductions would be more likely to receive greater media attention than children going missing because of family conflicts due to the relative rarity, engagement in pre-existing perceptions of vulnerability and lack of safety of the child, and for evoking a strong sense of collective fear from parents and the public alike (Miller et al. 2008; Newiss 2016; Walsh et al. 2016).

Researching the relationship between the level of media attention provided to missing children also shows how media journalists typically select unusual or dramatic items to publish which aim to attract the public’s attention (Gilchrist 2010; Gross and D’Ambrosio 2004). For instance, Shalev-Greene and Reddin (2015) examined journalist’s perspectives on providing media attention to missing children and found that those who were attractive, had high academic ability, had gone missing locally, were young, and had a good reputation in their community would be provided with high media coverage. In contrast, children who were living in care or foster homes, had a blurry or non-existing photograph, and had a history of criminal or delinquent activity were more likely than not to receive any media attention (Shalev-Greene and Reddin 2015). Demographic factors relating to the child’s ethnicity and gender have also been found to influence the likelihood of receiving media attention after going missing (Jeanis and Powers 2017; Min and Feaster 2010; Simmons and Woods 2015; Sommers 2017).

Attention

One of the central aims for publishing newsworthy events across the media is to grasp the reader’s attention (Gilchrist 2010; Gross and D’Ambrosio 2004). Increasing the attention of the public given to an event will also influence the likelihood of that individual being able to acquire and retain the information enclosed (Loftus 1979). In contrast, decreasing the level of the individual’s attention given to information to be encoded, also known as absent-mindedness (Schacter et al. 2003), would thus hinder the encoding of the information required to be attained. If the original information is not fully encoded at the first viewing, the individual would be more likely to forget these details in a shorter period of time or may inaccurately ‘fill in the gaps’ with similar and previously held information by reconstructing aspects of this memory trace (Radvansky 2017).

The time spent reading the information is an additional factor associated with attention and the overall ability to accurately retain information. As evidenced on the short-term and long-term memory effects of word recollection (Cary and Reder 2003; Nobel and Shiffrin 2001), it is argued that if an individual only has a limited amount of time available, or is willing to provide and to read the information presented, an increase in the number of items required to be retained would thus result in less overall time available for each individual item (Lampinen et al. 2012). As the time available per item decreases in addition to a reduced level of attention, the likelihood of accurately retaining and retrieving acquired information would be compromised significantly (Lampinen et al. 2012). Accordingly, it could be argued that as the available time decreases alongside the level of attention given by an individual, an increase in the number of items or length of information would result in the inability to accurately recall all this information.

Present Study

Despite their importance and the daily, worldwide usage, the research literature exploring the effectiveness of missing children appeals is limited (Drivsholm et al. 2017; Lampinen and Moore 2016; Lampinen and Sweeney 2014). The current research literature suggests that the effect of newsworthiness content, level of attention, and the ability to encode information accurately within a limited space of time may influence the overall effectiveness of information within missing children appeals to be successfully retained. The current study therefore sought to build on our current understanding of the effectiveness of missing children appeals further by aiming to explore the effectiveness of missing children appeals on the ability to accurately recall details of the missing child held within the descriptive content in the appeal. The research was motivated by current practices of missing children appeals, wherein an archival analysis of the descriptions used within media appeals of missing children and the circumstances surrounding the missing episodes had identified several key informational terms that are frequently presented.

The originality of this study is twofold. First, with this study, the researchers present a novel insight into the exploration of how the type of content and the length of descriptions used within missing children appeals influences the subsequent recall accuracy from members of the public in the UK during a free-recall task. Second, the study further explores how the content and the length of the descriptions used with missing children appeals influence the subsequent recall accuracy following a 3-day delay. Therefore, the objectives of the current study are (1) to explore whether the length of the description and the content enclosed in the description influence subsequent recall abilities, (2) to determine whether the length of time spent reading the mock appeal influences the subsequent recall ability, (3) to establish whether the participants’ level of confidence in their own recall ability is associated with overall recall ability, and (4) to determine whether the descriptive length and the content influences the subsequent recall ability following a 3-day delay.

Method

Design

The study adopted a mixed within-between-subject experimental design. The independent variables involved the mock appeal observed with four levels: short argument, short abduction, long argument, or long abduction, and the level of confidence in recall accuracy which ranged from 0 to 100% confident. The dependant variable in the current study comprised of the recall accuracy score which was calculated as the number of correct recalled items made from the mock appeal divided by the number of potential correct recall items available. This figure was then multiplied by 100 to derive a recall accuracy percentage score. The dependant variable was recorded at two time intervals: initial recall accuracy and delayed recall accuracy.

Sample

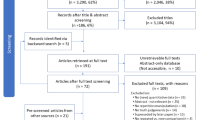

A total of 294 participants completed the online experimental study through snowball and convenience sampling methods, although 71 participants were removed from the data due to partial completions or misreading the free-recall task. Therefore, the final sample comprised of 223 participants (195 females; Mage = 24.42 years, SD = 10.16) who were included in the analysis for the initial study results. Of the final 223 participants, 56 (25.10%) were randomly assigned to the short argument description, 55 (24.70%) were randomly assigned to the short abduction description, 55 (24.70%) were randomly assigned to the long argument description, and 57 (25.60%) were randomly assigned to the long abduction description.

Following the initial experimental study, a secondary follow-up experimental task was performed 3 days later. From the 223 participants who had completed the initial study, 74 (33.18%) participants had dropped out and did not complete the delayed experimental task. Therefore, the final follow-up experimental sample comprised of 149 participants who were included in the analysis for the delayed study results. The participant conditions for the delayed task comprised of 36 (24.16%) within the short argument description, 32 (21.48%) within the short abduction description, 40 (26.85%) within the long argument description, and 41 (27.52%) within the long abduction description.

All research participants had been recruited through an online experimental recruitment system at the university and had received 0.5 credits for taking part. Participants were also recruited voluntarily through social media sites and did not receive any incentives for taking part. The participants were able to complete the experimental studies in any location and at any time which they found most comfortable. The study was accessed through the participants’ own home computer or mobile device using the Qualtrics software. Full ethical approval was granted by the School Research Ethics Panel at the university. Table 1 presents the demographic background statistics for the total sample and across each experimental condition.

Materials

Participants completed one initial online experimental study and one follow-up online experimental study 3 days after which comprised of the following.

Fictional Descriptions

The participants were randomly assigned to one of four fictional descriptive appeals of a missing child: short argument, short abduction, long argument, or long abduction. The fictional descriptions were developed by the primary researcher based upon archival analysis of media-released missing children descriptions within newspapers and social media posts. The fictional descriptions focused on the same fictional missing child to allow the descriptions to be compared during the analysis. All four descriptions included the same details relating to the fictional missing child’s name, age, and clothing worn when she was last seen, hair colour, eye colour, and the time and day of the missing episode. Moreover, all four descriptions had ended with the same information that requested individuals to contact their local neighbourhood policing team with any information relating to the missing child.

In addition to the identical missing child details presented within the descriptions, the two longer descriptions included additional information that includes the missing child’s ethnicity, height, and details surrounding the missing event. The first event included details of the child last seen heading towards a local bus stop which was two miles from her home address following an argument with her parents and was presented in the long argument description. The second event included details of the child entering an unknown male’s car, the colour of the car, the clothing worn by the unknown male, and the appearance of the unknown male presented in the long abduction description. Hence, the total number of words within each of the descriptions was 80 words for the short argument description, 84 words for the short abduction description, 143 words for the long argument description, and 160 words for the long abduction description. All four descriptions were timed in the background and hidden from the participant view. See Appendix 1 for the two argument fictional descriptions and target words and Appendix 2 for the two abduction fictional descriptions and target words.

Memory Distraction Task

Participants were asked to complete a short memory task in which they would be unable to go back to the previous task or forward to the next task for the duration of the distraction task. This task was included in the study to minimise the rehearsal of details included in the descriptions presented to the participants. All participants were presented with five individual tables comprising of five rows and two columns. Each of the five tables contained a total of ten single and randomised nouns which had been generated using an online random word generator (www.randomlists.com/nouns). Each of the five ten-word tables was displayed for 20 s and was presented sequentially. The memory distraction task totalled 50 words being presented in 100 s. Participants were asked to “try and remember as many of the words that will be displayed as possible as this may be tested later in the study.” The participants had not been informed of this task prior to the task commencing.

Free-Recall Task

The free-recall task comprised of a simple open-ended question that asked participants to “[…] recall as much information as possible that you can remember from the description of the missing child appeal that you had read at the start of the study.” Participants could input their responses within a single large text-field box. The free-recall task also included a small slidable scale ranging from 0% confident to 100% confident for the participants to indicate their level of confidence in their own recall accuracy of the descriptions read.

Demographic Survey

The demographic survey requested participants to specify their age in years, gender, ethnic background, highest level of education completed, current employment status, and current marital status. All responses presented allowed the participants to select one of the predetermined responses available excluding age which was open-ended.

Delayed Free-Recall Task

The delayed recall task was identical to the initial free-recall task and requested participants to try and “[…] recall as much information as possible that you can remember from the description of the missing child appeal that you had read at the start of the study presented three days ago.” Participants could once again input their responses within a single large text-field box. The delayed free-recall task also included a small slidable scale ranging from 0% confident to 100% confident for the participants to indicate their level of confidence in their own recall accuracy of the descriptions read.

Procedure

The current study was presented using the Qualtrics Inc. survey software (www.Qualtrics.com). Participants observing the study details through the university’s online experimental recruitment system or within the social media postings were requested to select the web link if they wished to participate. Participants were presented with an information sheet detailing the experimental purpose, storage, and collection of data, as well as ethical considerations and contact details of the primary researcher, followed by a consent form. The participants were randomly assigned through the Qualtrics system into one of the four available experimental conditions. Participants were presented with a descriptive mock appeal of a missing child and asked to simply observe the appeal. The participants were told they were free to spend as much or as little time required reading the description. All experimental conditions were timed in the background, hidden from participant view, to record how long each participant had spent reading the description.

After completing the experimental task, all participants were presented with a short word memory distraction task aimed to minimise the rehearsal of the details enclosed in the descriptive appeals. Participants were requested to try and memorise as many words as possible. The final segment of the experiment presented participants with a free-recall task which requested the participants to try and remember as much detail as possible within the missing child appeal they had read. The participants were also requested to indicate their level of confidence in their own recall accuracy from a slidable scale which ranged from 0% confident to 100% confident. This initial study ended with a demographic survey, details of the delayed experimental task, a request for an e-mail address to participate in the delayed task, and a full post-experiment debrief.

After a short 3-day break, participants who had provided an e-mail address were e-mailed to thank them for participating in the previous study and were presented with details of the follow-up study. The e-mail also contained a unique web link which has been generated by the Qualtrics software. The use of the unique web link allowed data responses from participants made in the first experimental study to be matched to the data responses made by participants in the follow-up study. Following the web link, participants were directed to a brief information page detailing the task and a consent form. Once consent was provided, participants were presented with an identical free-recall task that had been presented in the initial study 3 days previously. Participants were once again requested to try and recall as many details that they could remember from the mock missing child appeal they had read at the start of the study 3 days previously. The participants were also requested to indicate their level of confidence in their recall accuracy from a slidable scale which ranged from 0% confident to 100% confident. The delayed experimental task concluded with a full debrief. We thanked the participants once again for their participation across the two experimental studies.

Analysis

Participant data responses across the two experimental studies were input manually by the primary researcher into SPSS version 24 for analysis. Recall accuracy scores were calculated by summing the number of correct items recalled by participants during the free-recall task and dividing this figure by the maximum number of potential correct items available to be recalled. This figure was then multiplied by 100 to derive the recall accuracy percentage score. The maximum number of target items that were available to be recalled across all four descriptions was 16 items for the short argument description, 17 items for the short abduction description, 22 items for the long argument description, and 27 items for the long abduction experiment. See Appendices 1 and 2 for the descriptions with the target items included.

Recall items were deemed to be correct if they were identical to the information enclosed within the appeal that was read. For instance, if a participant indicates that they believed the missing child was 13 years old within the free-recall task, this would be classified as a correctly recalled item. In contrast, if the participant had indicated that they believed the missing child was 14 years old, this would be classified as an incorrect recalled item. It is important to note that the absence of a recalled item was not included in any of the subsequent analyses. Therefore, low error scores do not imply that no errors occurred; only a low number of incorrect items were presented. This is because participants may be unsure about the age of the child and so did not include an answer. If participants were required to provide an answer for each of the target items available, this could have influenced the rate of errors received in the studies.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

A series of chi-square tests were performed to establish whether there were any significant differences in demographic factors between the four experimental description conditions, finding no significant differences between the four experimental conditions and ethnicity (χ2 (18) = 14.60, p = .689), gender (χ2 (6) = 3.73, p = .713), highest level of education (χ2 (24) = 23.72, p = .478), employment status (χ2 (18) = 16.17, p = .581), or marital status (χ2 (9) = 7.42, p = .594). The age of participants between the four experimental conditions was also non-significantly different (F(3, 213) = 1.12, p = 0.347, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.015). Hence, the four initial experimental group samples are homogeneous and did not significantly differ in demographic factors.

A secondary series of chi-square tests were performed to establish whether there were any differences in demographic factors within the four delayed experimental conditions. The chi-square tests also found no significant differences between the four delayed experimental conditions and ethnicity (χ2 (18) = 25.07, p = .123), gender (χ2 (6) = 3.75, p = .711), highest level of education (χ2 (24) = 22.30, p = .561), employment status (χ2 (18) = 19.51, p = .361), or marital status (χ2 (9) = 5.84, p = .756). A one-way between groups ANOVA was performed to determine whether there is a significant difference between the four delayed experimental groups and the age of the participants finding a non-significant difference (F(3, 144) = 1.17, p = 0.325, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.024). Hence, the four delayed experimental group samples are homogeneous and did not significantly differ in demographic factors.

Initial Experimental Task

Length and Type of Content

The first objective of the study was to explore whether the length of the description and the type of content enclosed in the description influence the subsequent recall abilities of members of the public. The two-way factorial ANOVA found a significant effect for the length of descriptions (F(1, 219) = 8.42, p = 0.004, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.037), with shorter descriptions having higher recall accuracy scores (M = 48.74, SD = 21.85) than longer descriptions (M = 40.80, SD = 19.84). In contrast, the two-way factorial ANOVA found a non-significant main effect for the type of content enclosed in the descriptions on recall accuracy (F(1, 219) = 3.55, p = 0.061, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.016). There was also a non-significant interaction effect between the length of description and the type of content within the description on recall accuracy (F(1, 219) = 0.58, p = 0.45, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.003).

The research further sought to explore whether the length of the missing child descriptions and the type of content enclosed within the descriptions influenced the level of recall accuracy when only the same details equal across all four descriptions were considered. A one-way ANOVA found a significant difference between the descriptions in recall accuracy (F(3, 219) = 3.66, p = 0.013, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.048). A Tukey post-hoc test indicated that reading the short abduction description had significantly greater recall accuracy (M = 48.31, SD = 23.08) than reading the long argument description (M = 34.68, SD = 19.12) for identical details enclosed. No other description conditions were found to be significantly different in the level of recall accuracy on the details identical across the descriptions.

Time Duration

The second objective was to determine whether the length of time spent reading the mock appeal influences the subsequent recall ability. Pearson’s product-moment correlations found significant and positive associations for participants reading the short argument description (r = .35, n = 56, p = 0.009), the short abduction description (r = .39, n = 55, p = 0.003), and the long abduction description (r = .35, n = 57, p = 0.007). Hence, spending more time reading the descriptions are associated with greater recall accuracy. There were no significant associations found between time spent reading the long argument description and overall initial recall accuracy (r = .15, n = 55, p = 0.275).

Confidence

The third objective was to establish whether the participants’ level of confidence in their recall ability is associated with the overall recall ability. Pearson’s product-moment correlations found significant and positive associations for participants who read the short argument description (r = .71, n = 56, p = <0.001), the short abduction description (r = .57, n = 55, p = <0.001), the long argument description (r = .43, n = 55, p = 0.001), and the long abduction description (r = .68, n = 57, p = <0.001). Therefore, higher levels of participant confidence in their recall accuracy of the description that was read are associated with higher levels of overall recall accuracy.

Delayed Experimental Task

Length and Type of Content

The final objective was to determine whether descriptive length and content influences the subsequent recall ability following a 3-day delay. The two-way factorial ANOVA found a significant effect for the length of descriptions of the missing child (F(1, 145) = 13.15, p = <0.001, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.083) with short descriptions having higher delayed recall accuracy scores (M = 38.02, SD = 2.03) than the long descriptions (M = 28.11, SD = 1.83). Similarly, the findings also indicated a significant effect for the type of content enclosed within the descriptions of a missing child (F(1, 145) = 4.71, p = 0.032, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.031) with the more newsworthy abduction content having higher delayed recall accuracy scores (M = 36.03, SD = 1.96) than the non-newsworthy argument content (M = 30.10, SD = 1.90). There was a non-significant interaction effect between the length of the descriptions and type of content enclosed within the descriptions on delayed recall accuracy (F(1, 145) = 1.93, p = 0.167, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.013).

Similar to the initial study analysis, the researchers sought to explore recall accuracy when only the same details that are equal across all four descriptions were considered. The one-way ANOVA found a significant difference between the descriptions in recall accuracy (F(3, 145) = 3.59, p = 0.015, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.069). A Tukey post-hoc test indicated that reading the short abduction description had significantly greater recall accuracy (M = 39.06, SD = 16.73) than reading the long argument description (M = 26.25, SD = 15.38). No other descriptions were found to be significantly different in the level of recall accuracy on the details identical across the descriptions.

Confidence

The researchers aimed to ascertain whether the delayed recall accuracy scores are associated with participant delayed recall accuracy confidence scores. Pearson’s product-moment correlations found significant and positive associations between participant confidence and recall accuracy scores within the short argument description (r = .64, n = 36, p = <0.001), long argument description (r = .54, n = 40, p = < 0.001), and the long abduction description (r = .59, n = 41, p = <0.001). In contrast, there was a non-significant association between recall accuracy score and participant’s confidence score within the short abduction description (r = .27, n = 32, p = 0.132).

Comparison of Initial and Delayed Recall

Associations between the initial recall accuracy scores and the delayed recall accuracy scores were also investigated in the current study (Fig 1.). A two-way 2 (short or long) × 2 (argument or abduction) mixed between-group ANOVA with repeated measures on recall accuracy scores (initial and delayed) was performed. The results show a significant effect of recall accuracy scores, F(1, 145) = 111.71, p = <0.001, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.435 with significantly higher level of recall accuracy during the initial task (M = 46.20, SD = 1.70) compared to the delayed task (M = 33.01, SD = 1.35). The results also show a significant effect of the length of description, F(1, 145) = 5.18, p = 0.024, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.035, with shorter descriptions having significantly greater recall accuracy scores (M = 43.45, SD = 2.07) than longer descriptions (M = 35.77, SD = 1.90). In contrast, the results indicated that there was not a significant effect for the type of content, F(1, 145) = 10.85, p = 0.094, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.001, or on the interaction effect between the length of description and the type of content, F(1, 145) = 2.60, p = 0.109, \( {n}_p^2 \) = 0.018, on recall accuracy scores.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to explore the effectiveness of missing children appeals on the ability to accurately recall details of the missing child held within the descriptive content in the appeal. Specifically, the researchers sought to determine whether the length of description and the type of content enclosed within the description of a missing child appeal influences the subsequent recall accuracy of the details enclosed within the appeal immediately after reading the description and again after a 3-day delay. The overall results suggest that the length of the descriptions does significantly influence recall accuracy both after reading the appeal and after a 3-day delay. Moreover, the type of content enclosed within the descriptions also influences recall accuracy after a 3-day delay. Time spent reading the description and level of confidence in own recall accuracy was also found to be significantly associated with overall recall accuracy.

Influence of Length and Type of Content

The results indicate that participants who had read shorter descriptions are significantly more likely to have higher recall accuracy than participants who read longer descriptions. This effect was present both immediately after reading the description and after a 3-day break. This finding is therefore supported by Cary and Reder (2003) whose examination of recognition accuracy scores for participants reading lists of words found individuals reading the shorter 16-word list had significantly greater recognition accuracy than individuals reading the long list of 64 words. It can be argued that Cary and Reder (2003) focused solely on individual words required to be memorised and then recognised, whilst the current study focused on short paragraph structures and exploring recall rather than recognition. Nevertheless, this study is the closest available research to the current study with the overall aim of pursuing the recall accuracy for a list of words. Additionally, Lampinen et al. (2012) argue that individuals with a limited amount of time available or who are willing to provide to read the required items are less likely to recall the information. This is due to the increase in the number of items to be remembered with a decrease in the maximum available time available to remember each individual item (Lampinen et al. 2012).

Similar to length of content, the results also show that participants who had read the descriptions with more newsworthy content had significantly greater recall accuracy than participants who had read descriptions with non-newsworthy content. This effect was only significant after a 3-day break. This result is a novel finding with previous literature not exploring this influence on recall accuracy from missing children appeals as they typically focus on description list length recall ability (Cary and Reder 2003) or newsworthiness items relating to an offender or victim portrayal across the media (Gekoski et al. 2012; Peelo et al. 2004). Hence, the current study lays the foundation for future research to explore the effects of the type of content enclosed within missing children appeals on recall accuracy of the public further.

Influence of Time

The results had further identified that the amount of time spent reading the descriptions did have a significant influence on the recall accuracy from members of the public. Specifically, participants who had read the description for a greater time duration were significantly more likely to generate a higher level of recall accuracy of details enclosed within the appeal than individuals who had read the description for a shorter time duration. The effect of time on the subsequent recall accuracy from members of the public could perhaps be explained by the improved ability to fully maximise encoding of the information that was read from short-term memory into long-term memory (Kapardis 2014). The study by Hunt et al. (2019) supports this finding further as participants who had observed a missing child photograph for a longer duration had significantly greater identification accuracy from a line-up than participants who had observed the photographs for a shorter duration. The work by Yarmey et al. (2002) also supports this notion as their work found that members of the public who had observed and interacted with a confederate target asking for directions for 30 s had superior identification recall accuracy than individuals who had only observed and interacted with the confederate target for 5 s. However, greater exploration of the influence between time spent reading missing children appeals and the affect it may have on the overall recall accuracy is required to understand this effect further.

Influence of Delay

Finally, the results also show that the recall accuracy of the details enclosed within a missing child appeal significantly decreases as the time between reading the description and requiring to recall the information increases. This effect was only significant for length of the description and not for the type of content enclosed within the description. Whilst not relating to paragraph descriptions, this finding supports the work by Cary and Reder (2003) who analysed the recognition accuracy of different list-length of words from participants and found that regardless of the number of words required to be recalled, all participants had significantly greater recognition accuracy prior to the short delay than they did following the short delay. Despite this study exploring recollection of words and not full paragraph descriptions, it does demonstrate the effect that a delay has on the subsequent recall ability. Likewise, Hunt et al. (2019) found that participants had significantly lower initial identification accuracy after a 3-day delay in recall than they did immediately after observing the missing child photograph. Additional research however would thus do well to explore this effect further as our current understanding on the association between missing children appeals and a delay in recall is limited.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study presents a novel insight into missing children appeals and builds on the limited literature, understanding how effective these appeals are in helping to locate missing children. Nevertheless, there are some limitations which must be addressed. First, the researchers sought to achieve a representative sample for the UK population. However, the majority of the research participants had a white ethnic background, were students and were female. Future research should seek to develop a more representative sample to explore the effectiveness of missing children descriptive appeals to determine whether the background characteristics of the participants and of the missing child in the appeal influence the subsequent recall ability. Current research findings suggest that the gender and the age of both parties have long been associated with differences in recall ability (Kapardis 2014). Nevertheless, the current research sample did participate from and live within a varied geographical location base across the UK which helps to minimise the effect of location biases on identification ability.

Second, the descriptions utilised within the study were fictional which may have contributed to the results. The descriptions presented to the participants were designed to share similar factors which help to improve reliable comparability when determining the differences in type of content and the length of descriptions on recall accuracy. The use of more realistic descriptions may thus prove advantageous to explore recall ability as the differences that arose within this current study may be due to the difference in content between the four descriptions. For instance, including additional descriptions of other missing children may provide a deeper insight into appeal effectiveness as the demographic characteristics of the missing children or the reader or the locations in which the children had gone missing in relation to the current locations of the reader may also influence recall ability. Hence, future research could replicate the study utilising previous and genuine missing children descriptive appeals to determine whether the type of content and the length of the descriptions used also influences identification accuracy.

Finally, once the participants had read the description, they were required to complete a short and simple word-memory distraction task to minimise rehearsal of the details enclosed. As such, the distraction task may not have fully prevented the research participants from rehearsing the details they had just read which would influence the rate or accuracy during the free-recall task. Future research could therefore include a much longer and cognitively challenging distraction task such as completing a puzzle to fully explore this effect further.

Conclusion

In summary, the current findings suggest that reducing the length of the details enclosed within missing children appeals significantly improves the recall accuracy of these details by members of the general public. The results had further shown that as the length of time between reading the appeal and requiring to recall the information increases, their recall accuracy significantly decreases. Therefore, these findings show significant implications for the current method of presenting missing children appeals. As the amount of information within the appeal increases, the amount of time willing to be devoted to the information by members of the public decreases. Subsequently, this effect will significantly reduce the ability of members of the public to be able to recall this information accurately. Improving individual level of confidence in their own recall accuracy is also found to improve the overall recall accuracy of the information enclosed within the appeal.

This study is exploratory and therefore provides the foundations for future research to build on these findings further. Future research could improve our understanding of the effectiveness of missing children appeals to identify additional factors that are associated with improving recall accuracy of information presented within an appeal. The research findings presented are by no means an argument to reduce the amount of information included within missing children appeals, but an argument to explore this effect further to identify the most appropriate balance of disseminating key information required to be known about the child and the ability to accurately recall this information at a later date.

References

Araujo T, van der Meer TGLA (2018) News values on social media: exploring what drives peaks in user activity about organisations on Twitter. Journalism:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918809299

Cary M, Reder LM (2003) A dual-process account of the list-length and strength-based mirror effects in recognition. J Mem Lang 49(2):231–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-596x(03)00061-5

Drivsholm M, Moralis D, Shalev-Greene K, Woolnough P (2017) Once missing never forgotten? Results of scoping research on the impact of publicity appeals in missing children cases. Retrieved from: https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/portal/files/7514950/Once_Missing_Never_Forgotten_final.pdf

Fyfe NR, Stevenson O, Woolnough P (2014) Missing persons: the processes and challenges of police investigation. Policing and Society: An International Journal of Research and Policy:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2014.881812

Galtung J, Ruge MH (1965) The structure of foreign news: the presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. J Peace Res 2(1):64–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336500200104

Gekoski A, Gray JM, Adler JR (2012) What makes a homicide newsworthy? UK national tabloid newspaper journalists tell all. Br J Criminol 52(6):1212–1232. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azs047

Gilchrist K (2010) “Newsworthy” victims? Fem Media Stud 10(4):373–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2010.514110

Gross K, D’Ambrosio L (2004) Framing emotional response. Polit Psychol 25(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00354.x

Gruenewald J, Chermak SM, Pizarro JM (2013) Covering victims in the news: what makes minority homicides newsworthy? Justice Q 30(5):755–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2011.628945

Hayden C, Shalev-Greene K (2016) The blue light social services? Responding to repeat reports to the police of people missing from institutional locations. Policing and Society:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2016.1138475

Hill L, Taylor J, Richards F, Reddington S (2016) ‘No-one runs away for no reason’: understanding safeguarding issues when children and young people go missing from home. Child Abuse Rev 25(3):192–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2322

Hunt D, Ioannou M, Synnott J (2019) Missing children photograph appeals: does the number of appeals affect identification accuracy following a short recall delay? J Police Crim Psychol 34(4):417–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-019-09337-2

Jeanis MN, Powers RA (2017) Newsworthiness of missing persons cases: an analysis of selection bias, disparities in coverage, and the narrative framework of news reports. Deviant Behav 38(6):668–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2016.1197618

Johnstone JWC, Hawkins DF, Michener A (1994) Homicide reporting in Chicago dailies. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 71(4):860–872. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909407100410

Kapardis A (2014) Psychology and law: a critical introduction, 4th edn. Cambridge University Press, New York

Kiepal L, Carrington PJ, Dawson M (2012) Missing persons and social exclusion. Can J Sociol 37(2):137–168 Retrieved from: https://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php.CJS/article/viewFile/10114/14107

Lampinen JM, Moore KN (2016) Missing person alerts: does repeated exposure decrease their effectiveness? J Exp Criminol 12(4):587–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-016-9263-1

Lampinen JM, Sweeney LN (2014) Associated adults: prospective person memory for family abducted children. J Police Crim Psychol 29(1):22–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-013-9120-3

Lampinen JM, Miller JT, Dehon H (2012) Depicting the missing: prospective and retrospective person memory for age progressed images. Appl Cogn Psychol 26(2):167–173. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1819

Loftus EF (1979) The malleability of human memory: information introduced after we view an incident can transform memory. Am Sci 67(3):312–320 Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27849223

Lundman RJ (2003) The newsworthiness and selection bias in news about murder: comparative and relative effects of novelty and race and gender typifications on newspaper coverage of homicide. Sociol Forum 18(3):357–386. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1025713518156

Miller JM, Kurlycheck M, Hansen JA, Wilson K (2008) Examining child abduction by offender type patterns. Justice Q 25(3):523–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/0741882082241697

Min S, Feaster JC (2010) Missing children in national news coverage: racial and gender representations of missing children cases. Communication Research Reports 27(3):207–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824091003776289

Missing People (2018) Key information. Retrieved from: https://www.missingpeople.org.uk/about-us/about-the-issue/research/76-keyinformation2.html

Moscowitz L, Duvall S (2011) Every parent’s worst nightmare. J Child Media 5(2):147–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2011.558267

National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children (2015) National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children Annual Report. Retrieved from: http://www.missingkids.com/content/dam/ncmec/en_us/publications/ncmec2015.pdf

National Crime Agency [NCA] (2017) Missing persons data report 2015/2016. Retrieved from: http://missingpersons.police.uk/en-gb/resources/downloads/download/61

Newiss G (2005) A study of the characteristics of outstanding missing persons: implications for the development of police risk assessment. Polic Soc 15(2):212–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439460500071655

Newiss G (2016) Police-recorded child abduction and kidnapping 2014/15. Retrieved from: http://www.actionagainstabduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Action_Against_Abduction_Child_Abduction_Report_2016.pdf

Nobel PA, Shiffrin RM (2001) Retrieval processes in recognition and cued recall. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 27(2):384–413. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-7393.27.2.384

Peelo M, Francis B, Soothill K, Pearson J, Ackerley E (2004) Newspaper reporting and the public construction of homicide. Br J Criminol 44(2):256–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/44.2.256

Radvansky GA (2017) Human memory. Routledge, New York

Schacter DL, Chiao JY, Mitchell JP (2003) The seven sins of memory: implications for self. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1001(1):226–239. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1279.012

Shalev-Greene K, Reddin J (2015) Media bias in cases of children who go missing [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from Missing Children Europe. Portals: http://missingchildreneurope.eu/Portals/0/Docs/Media%20bias.pdf

Shalev-Greene K, Schaefer M, Morgan A (2009) Investigating missing person cases: how can we learn where they go or how far they travel? International Journal of Police Science & Management 11(2):123–116. https://doi.org/10.1350/ijps.2009.11.2.116

Simmons C, Woods J (2015) The overrepresentation of white missing children in national television news. Communication Research Reports 32(3):239–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2015.1052898

Smeaton E, Rees G (2004) Running away in South Yorkshire: research into the incidence and nature of the problem in Sheffield, Rotherham, Barnsley & Doncaster. Retrieved from: https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/tcs/research_docs/running_away.pdf

Sommers Z (2017) Missing white woman syndrome: an empirical analysis of race and gender disparities in online news coverage of missing persons. J Criminal Law Criminol 106(2):275–314 Retrieved from: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7586&context=jclc

Sweeney LN, Lampinen JM (2012) The effect of presenting multiple images on prospective and retrospective person memory for missing children. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 1(4):235–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2012.08.001

Taylor J, Boisvert D, Sims B, Garver C (2013) An examination of gender and age in print media accounts of child abductions. Criminal Justice Studies 26(2):151–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478601x.2012.724683

Trilling D, Tolochko P, Burscher B (2017) From newsworthiness to shareworthiness: how to predict news sharing based on article characteristics. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94(1):38–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016654682

Walsh JA, Krienert JL, Comens CL (2016) Examining 19 years of officially reported child abduction incidents (1995-2013): employing a four category typology of abduction. Crim Justice Stud 29(1):21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478601x.2015.1129690

Yarmey AD, Jacob J, Porter A (2002) Person recall in field settings. J Appl Soc Psychol 32(11):2354–2367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb01866.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed within the study that involved human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Huddersfield and with the ethical standards of the British Psychological Society Code of Ethics and Conduct (2018).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Fears Grow for Missing 13-Year-Old Schoolgirl.

Fears are growing for a missing 13 year old schoolgirl who disappeared after a family argument.

Abigail Walters had gone missing at around 5 pm on Tuesday evening an argument with her parents about a new boyfriend.

Abigail was last seen wearing a red fashion scarf, plain white t-shirt, blue jeans and white Nike trainers. She has long blond hair, green eyes and usually goes by the name Abby.

Any information should be reported to your local neighbouring policing team.

Fears Grow for Missing 13-Year-Old Schoolgirl.

The family of a missing 13 year old schoolgirl are desperate to find her after she disappeared following an argument with her parents about a new boyfriend.

Abigail Walters had gone missing at around 5 pm on Tuesday evening after storming out of the family home. She was last seen heading towards the bus stop located two miles away from her home.

Abigail was last seen wearing a red fashion scarf, plain white t-shirt, blue jeans and white Nike trainers. She is described as white, 5 ft. 1in tall, of slim build, with long blond hair and green eyes. She usually goes by the name Abby.

A spokesman for the police said that they were highly concerned for her welfare and hope to find her soon, She has now been missing for 7 h.

Any information should be reported to your local neighbouring policing team.

Appendix 2

Fears Grow for Missing 13-Year-Old Schoolgirl.

Fears are growing for a missing 13 year old schoolgirl who disappeared with an unknown male.

Abigail Walters had gone missing at around 5 pm on Tuesday evening after being seen getting into the car of an unknown male by her friends.

Abigail was last seen wearing a red fashion scarf, plain white t-shirt, blue jeans and white Nike trainers. She has long blond hair, green eyes and usually goes by the name Abby.

Any information should be reported to your local neighbouring policing team.

Fears Grow for Missing 13-Year-Old Schoolgirl.

The family of a missing 13 year old schoolgirl are desperate to find her after she disappeared with an unknown male after finishing school.

Abigail Walters had gone missing at around 5 pm on Tuesday evening after being seen geeting into the car of an unknown male by her friends. The car is described as baing a silver hatchback with black tinted windows. The male is described as being white, in his mid-thirties and wearing a blue patterned t-shirt.

Abigail was last seen wearing a red fashion scarf, plain white t-shirt, blue jeans and white Nike trainers. She is described as white, 5 ft. 1in tall, of slim build, with long blond hair and green eyes. She usually goes by the name Abby.

A spokesman for the police said that they were highly concerned for her welfare and hope to find her soon, She has now been missing for 7 h.

Any information should be reported to your local neighbouring policing team.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hunt, D., Ioannou, M. & Synnott, J. Effectiveness of Descriptions in Missing Children Appeals: Exploration of Length, Type of Content and Confidence on Recall Accuracy. J Police Crim Psych 35, 336–347 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-019-09362-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-019-09362-1