Abstract

Purpose of Review

To review randomized interventional clinical and imaging trials that support lower targeted atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol goals in “extreme” and “very high” atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk settings. Major atherosclerotic cardiovascular event (MACE) prevention among the highest risk patients with ASCVD requires aggressive management of global risks, including lowering of the fundamental atherogenic apolipoprotein B-associated lipoprotein cholesterol particles [i.e., triglyceride-rich lipoprotein remnant cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and lipoprotein(a)]. LDL-C has been the long-time focus of imaging studies and randomized clinical trials (RCTs). The 2004 adult treatment panel (ATP-III) update recognized that the long-standing targeted LDL-C goal of < 100 mg/dL potentially fostered substantial undertreatment of the very highest coronary heart disease (CHD) risk individuals and was lowered to < 70 mg/dL as an “optional” goal for “very high” 10-year CHD [CHD death + myocardial infarction (MI)] risk exceeding 20%. This evidence-based guideline change was supported by the observed benefits demonstrated in the high-risk primary and secondary prevention populations in the Heart Protection Study (HPS), the acute coronary syndrome (ACS) population in the Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 trial (PROVE-IT), and the secondary prevention population in the Reversal of Atherosclerosis with Aggressive Lipid Lowering (REVERSAL) intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) study. Subsequent national and international guidelines maintained a targeted LDL-C goal < 70 mg/dL, or a threshold for management of > 70 mg/dL for patients with CHD, CHD risk equivalency, or ASCVD.

Recent Findings

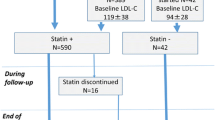

Subgroup or meta-analyses of several RCTs, IVUS imaging studies, and the ACS population in IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT) supported the evidence-based 2017 American Association Clinical Endocrinologist (AACE) guideline change establishing a targeted LDL-C goal < 55 mg/dL, non-HDL-C < 80 mg/dl, and apolipoprotein B (apo B) < 70 mg/dL for patients at “Extreme” ASCVD risk, i.e., 10-year 3-point-MACE-composite (CV death, non-fatal MI, or ischemic stroke) risk exceeding 30%. Moreover, with no recognized lower-limit-associated intolerance or safety issues, even more intensive lowering of atherogenic cholesterol levels is supported by the following evidence base: (1) analysis of eight high-intensity statin-based prospective secondary prevention IVUS atheroma volume regression trials; (2) a distribution analysis of on-treatment, ezetimibe and background-statin, of the very low LDL-C levels reached and CVD event risk in the IMPROVE-IT ACS population; (3) the secondary prevention Global Assessment of Pl\aque Regression With a PCSK9 Antibody as Measured by Intravascular Ultrasound (GLAGOV) on background-statin; and (4) the secondary prevention population of Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk (FOURIER). By example, in FOURIER, the population on background-statin at a baseline median 92 mg/dL achieved median LDL-C level of 30 mg/dL and non-HDL-C to < 65 mg/dl, and apo B to < 50 mg/dL, and subgroup and post hoc analyses all demonstrated additional ASCVD event reduction benefits as LDL-C was further reduced.

Summary

The level of ASCVD risk determines the degree, urgency, and persistence in global risk management, including fundamental atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol particle lowering. “Extreme” risk patients may require extremely low targeted LDL-C, non-HDL-C and apo B goals; such efforts, implied by more recent interventional trials and analyses, are aimed at maximal atheroma plaque regression, stabilization, and MACE event reduction with the aspiration of improved quality lifespan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

American College of Cardiology

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- AHA:

-

American Heart Association

- apo B:

-

Apolipoprotein B

- ARR:

-

Absolute risk reduction

- ASCVD:

-

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- ATP-III:

-

Adult treatment panel

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- MACE:

-

Major adverse cardiovascular events

- NCEP-ATP:

-

National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III

- NNT:

-

Number needed to treat

- Non-HDL-C:

-

Non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol

- RRR:

-

Relative risk reduction

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- FOURIER:

-

Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research with PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects with Elevated Risk

- GLAGOV:

-

Global Assessment of Plaque Regression with a PCSK9Antibody as Measured by Intravascular Ultrasound

- HPS:

-

Heart Protection Study

- IMPROVE-IT:

-

IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial

- JUPITER:

-

Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin

- ODYSSEY:

-

Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes After an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment with Alirocumab

- PROVE-IT:

-

Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22) Trial

- REVERSAL:

-

REVERSal of atherosclerosis with Aggressive lipid Lowering trial

- TNT:

-

Treating to New Targets

- VOYAGER:

-

An IndiVidual Patient Meta-Analysis Of Statin TherapY in At-Risk Groups: Effects of Rosuvastatin, Atorvastatin and Simvastatin

- RCTs:

-

Randomized Clinical Trials

- IVUS:

-

Coronary Intravascular Ultrasound

- LDL-C:

-

Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

- PAV:

-

Percent Atheroma Volume

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Bruckert E, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2459–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144. This is an exquisitely concise review article of the atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol principle evidence; it presents the case and satisfied criteria for LDL causality appraising evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical intervention studies.

Klarin D, Zhu QM, Emdin CA, Chaffin M, Horner S, McMillan BJ, et al. Genetic analysis in UK Biobank links insulin resistance and transendothelial migration pathways to coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2017;49(9):1392–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3914.

Paththinige CS, Sirisena ND, Dissanayake V. Genetic determinants of inherited susceptibility to hypercholesterolemia - a comprehensive literature review. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16(1):103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-017-0488-4.

Ramasamy I. Update on the molecular biology of dyslipidemias. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;454:143–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2015.10.033.

Khera AV, Emdin CA, Drake I, Natarajan P, Bick AG, Cook NR, et al. Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2349–58. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1605086.

Steinberg D. The cholesterol controversy is over: why did it take so long? Circulation. 1989;80(4):1070–8.

Steinberg D, Witzum JL. Lipoprotein and atherogenesis: current concepts. JAMA. 1990;264:3047–52.

Steinberg D. An interpretive history of the cholesterol controversy: part I. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1583–93.

Robinson JG, Williams KJ, Gidding S, Borén J, Tabas I, Fisher EA, et al. Eradicating the burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by lowering apolipoprotein B lipoproteins earlier in life. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(20):e009778. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.009778.

Sniderman AD. Applying apoB to the diagnosis and therapy of the atherogenic dyslipoproteinemias: a clinical diagnostic algorithm. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2004;15:433–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mol.0000137220.39031.3b.

Sniderman A, Shapiro S, Marpole D, Skinner B, Teng B, Kwiterovich PO Jr. Association of coronary atherosclerosis with hyperapobetalipoproteinemia [increased protein but normal cholesterol levels in human plasma low density (β) lipoproteins]. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1980;77(1):604–8.

Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and the progression of coronary artery disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1995;6:209–14.

Alaupovic P, Mack WJ, Knight-Gibson C, Hodis HN. The role of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein families in the progression of atherosclerotic lesions as determined by sequential coronary angiography from a controlled clinical trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:715–22.

Grundy SM. Hypertriglyceridemia, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:18B–25B.

Krauss RM. Atherogenicity of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:13B–7B.

Assmann G, Schulte H, Funke H, von Eckardstein A. The emergence of triglycerides as a significant independent risk factor in coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 1998;19(suppl M):M8–M14.

Austin MA, Hokanson JE, Edwards KL. Hypertriglyceridemia as a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:7B–12B.

Sacks FM, Alaupovic P, Moye LA, Cole TG, Sussex B, Stampfer MJ, et al. VLDL, apolipoproteins B, CIII, and E, and risk of recurrent coronary events in the Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) trial. Circulation. 2000;102:1886–92.

Rosenson RS, Davidson MH, Hirsh BJ, Kathiresan S, Gaudet D. Genetics and causality of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(23):2525–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.042.

National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection E, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in A. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421.

Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Ray K, Borén J, Andreotti F, Watts GF, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(23):2844–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq386.

Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A. Lipoprotein (a) as a cause of cardiovascular disease: insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(11):1953–75. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R071233.

Tsimikas S, Brilakis ES, Miller ER, McConnell JP, Lennon RJ, Kornman KS, et al. Oxidized phospholipids, Lp(a) lipoprotein, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(1):46–57. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa043175.

Kiechl S, Willeit J, Mayr M, Viehweider B, Oberhollenzer M, Kronenberg F, et al. Oxidized phospholipids, lipoprotein(a), lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 activity, and 10-year cardiovascular outcomes: prospective results from the Bruneck study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(8):1788–95. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.145805.

Tselepis AD. Oxidized phospholipids and lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 as important determinants of Lp(a) functionality and pathophysiological role. J Biomed Res. 2016;31. https://doi.org/10.7555/JBR.31.20160009.

Sniderman AD. Differential response of cholesterol and particle measures of atherogenic lipoproteins to LDL lowering therapy: implications for clinical practice. J Clin Lipidol. 2008;2:36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2007.12.006.

Sniderman AD, Williams K, Contois JH, Monroe HM, McQueen MJ, de Graaf J, et al. A meta-analysis of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B as markers of cardiovascular risk. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:337–45. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.959247.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–39. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E.

Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, et al. Comparison of intensive and moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–502. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa040583.

•• Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387–97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1410489. The ground-breaking landmark IMPROVE-IT trial demonstrated that ezetimibe, a non-statin, against the background of statin therapy, was able to significantly lower atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol biomarkers, LDL-C, non-HDL-C, and Apo B, to <55 mg/dL, <80 mg/dL and <70 mg/dL, respectively) and significantly reduce clinical ASCVD events, further validating the atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol principle.

•• Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1713–22. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1615664. The ground-breaking landmark FOURIER trial demonstrated that a PCSK9 inhibitor, evolocumab, a non-statin, against the background of statin therapy, in otherwise stable patients with established ASCVD, i.e. very high risk and extreme risk was able to significantly lower atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol biomarkers, LDL-C, non-HDL-C, and Apo B, to very low levels, <30 mg/dL, <65 mg/dL and <50 mg/dL, respectively) and significantly reduce clinical ASCVD events.

Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3.

Wiviott SD, Cannon CP, Morrow DA, Ray KK, Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, et al. Can low-density lipoprotein be too low? The safety and efficacy of achieving very low low-density lipoprotein with intensive statin therapy: a PROVE IT-TIMI 22 substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1411–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.064.

LaRosa JC, Grundy SM, Kastelein JJ, Kostis JB, Greten H, for the Treating to New Targets (TNT) Steering Committee and Investigators. Safety and efficacy of atorvastatin-induced very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in patients with coronary heart disease (a post hoc analysis of the TNT to new targets [TNT] study). Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:747–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.102.

Leeper NJ, Ardehali R, de Goma EM, Heidenreich PA. Statin use in patients with extremely low low-density lipoprotein levels is associated with improved survival. Circulation. 2007;116:613–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.694117.

Hsia J, MacFayden J, Monyak J, Ridker P. Cardiovascular risk reduction and adverse events among subjects attaining LDL-C <50 mg/dL with rosuvastatin: the JUPITER trial. JACC. 2011;57:1666–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.082.

Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, Blazing MA, De Ferrari GM, Park JG, Murphy SA, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of achieving very low levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: a prespecified analysis of the IMPROVE-IT trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(5):547–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.0083.

•• Giugliano RP, Pedersen TR, Park JG, De Ferrari GM, Gaciong ZA, Ceska R, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of achieving very low LDL-cholesterol concentrations with the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab: a prespecified secondary analysis of the FOURIER trial. Lancet. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32290-0. This prespecified subgroup analysis of FOURIER demonstrated a highly significant monotonic relationship between low LDL-C concentrations and lower risk of the primary and secondary efficacy composite endpoints extending from an LDL-C of 100 mg/dL to 7 mg/Dl, and no safety concerns.

Boekholdt SM, Arsenault BJ, Mora S, Pedersen TR, LaRosa JC, Nestel PJ, et al. Association of LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B levels with risk of cardiovascular events among patients treated with statins: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;307:1302–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.366.

Boekholdt SM, Hovingh GK, Mora S, Arsenault BJ, Amarenco P, Pedersen TR, et al. Very low levels of atherogenic lipoproteins and the risk for cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis of statin trials. JACC. 2014;64(5):485–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.615.

•• Nicholls SJ, Puri R, Anderson TJ, Ballantyne CM, Cho L, Kastelein JJP, et al. Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: the GLAGOV randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(22):2373–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.16951. The GLAGOV intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) trial demonstrated that a PCSK9 inhibitor, evolocumab, a non-statin, against the background of statin therapy, was able to significantly lower atherogenic lipoprotein cholesterol biomarkers, LDL-C, non-HDL-C, and Apo B, to <37 mg/dL, <58 mg/dL and <43 mg/dL, respectively, and significantly induce regression reduce plaque volume, a post-hoc LOESS plot (figure 4) that showed a linear relationship between achieved LDL-C level and PAV progression for LDL-C levels ranging from 110 mg/dL to as low as 20mg/dL.

Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, Brown BG, Ganz P, Vogel RA, et al. Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1071–80. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.9.1071.

Puri R, Nissen SE, Shao M, Uno K, Kataoka Y, Kapadia SR, et al. Impact of baseline lipoprotein and C-reactive protein levels on coronary atheroma regression following high-intensity statin therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1465–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.08.009.

Smith SC Jr, Allen J, Blair SN, Bonow RO, Brass LM, Fonarow GC, et al. AHA/ACC Guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 Update: Endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2006;113:2363–72. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174516.

Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, Goldberg RB, Howard BV, Stein JH, et al. Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk: consensus conference report from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1513–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.034.

European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation, Reiner Z, Catapano AL, De Backer G, Graham I, Taskinen MR, et al. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–818. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158.

Jellinger PS, Smith DA, Mehta AE, Ganda O, Handelsman Y, Rodbard HW, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ guidelines for management of dyslipidemia and prevention of atherosclerosis. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(Suppl 1):1–78.

Anderson TJ, Grégoire J, Hegele RA, Couture P, Mancini GB, McPherson R, et al. 2012 update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:151–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2012.11.032.

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, Blonde L, Bloomgarden ZT, Bush MA, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Comprehensive Diabetes Management Algorithm 2013 consensus statement. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(Suppl 2):1–48.

Expert Dyslipidemia Panel of the International Atherosclerosis Society Panel. An International Atherosclerosis Society position paper: global recommendations for the management of dyslipidemia, full report. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8:29–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2013.12.005.

Jacobson TA, Ito MK, Maki KC, Orringer CE, Bays HE, Jones PH, et al. National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia: part 1-executive summary. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8:473–88.

Jacobson TA, Ito MK, Maki KC, Orringer CE, Bays HE, Jones PH, et al. National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia: part 1 – full report. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9:129–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2015.02.003.

Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, Wiklund O, Chapman MJ, Drexel H, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias: The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) Developed with the special contribution of the European Assocciation for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Atherosclerosis. 2016;253:281–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.08.018.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM, Birtcher KK, Daly DD Jr, DePalma SM, et al. 2016 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of non-statin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(1):92–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.519.

•• Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, Bloomgarden ZT, Fonseca VA, Garber AJ, et al. 2017 AACE/ACE Guidelines American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Guidelines for Management of Dyslipidemia and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(Supplement 2):1–87. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP171764.APPGL. The 2017 AACE/ACE dyslipidemia guideline introduced the concept of partitioning the very high ASCVD risk category in recognition of the more ominous multi-morbidities described by the ‘extreme’ risk category defined generally in epidemiology and randomized clinical trials 10-year 3-point MACE exceeding 30% and based on the results of the IMPROVE-IT trial, that demonstrated additional benefits beyond guidelines at that time justified lowered targeted atherogenic cholesterol markers, LDL-C, non-HDL-C, and Apo B goals <55 mg/dL, <80 mg/dL and <70 mg/dL, respectively.

Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2889–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002.

Karlson BW, Nicholls SJ, Lundman P, Palmer MK, Barter PJ. Achievement of 2011 European low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) goals of either <70 mg/dL or 50 percent reduction in high-risk patients: results from VOYAGER. Atherosclerosis. 2013;228:265–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.02.027.

Wong ND, Young D, Zhao Y, Nguyen H, Caballes J, Khan I, et al. Prevalence of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association statin eligibility groups, statin use, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol control in US adults using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2012. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(5):1109–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2016.06.011.

Cannon CP, Khan I, Klimchak AC, Reynolds MR, Sanchez RJ, Sasiela WJ. Simulation of lipid-lowering therapy intensification in a population with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(9):959–66. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2289.

Kataoka Y, St John J, Wolski K, Uno K, Puri R, Tuzcu EM, et al. Atheroma progression in hyporesponders to statin therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(4):990–5. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304477.

O’Keefe JH Jr, Cordain L, Harris WH, Moe RM, Vogel R. Optimal low-density lipoprotein is 50 to 70 mg/dl: lower is better and physiologically normal. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2142–6.

Martin SS, Blumenthal RS, Miller M. LDL cholesterol: the lower the better. Med Clin N Am. 2012;96:13–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2012.01.009.

Giugliano RP, Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Nicolau JC, Corbalán R, Špinar J, et al. Benefit of adding ezetimibe to statin therapy on cardiovascular outcomes and safety in patients with versus without diabetes mellitus: results from IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial). Circulation. 2018;137(15):1571–82. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030950.

Murphy SA, Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, White JA, Lokhnygina Y, et al. Reduction in total cardiovascular events with ezetimibe/simvastatin post-acute coronary syndrome: the IMPROVE-IT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:353–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.077.

Eisen A, Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Bohula EA, Park JG, Murphy SA, et al. The benefit of adding ezetimibe to statin therapy in patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery and acute coronary syndrome in the IMPROVE-IT trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(48):3576–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw377.

Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, Raal FJ, Blom DJ, Robinson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of evolucumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1500–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1500858.

Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, Bergeron J, Luc G, Averna M, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1489–99. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1501031.

• Ray KK, Ginsberg HN, Davidson MH, Pordy R, Bessac L, Minini P, et al. Reductions in atherogenic lipids and major cardiovascular events: a pooled analysis of 10 ODYSSEY trials comparing alirocumab to control. Circulation. 2016;134:1931–43. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024604. Pooled analyses of the PCSK9 mAb, alirocumab, in its ODYSSEY Phase 3 Trials clearly demonstrated the practicability of reducing atherogenic cholesterol markers to very low levels, i.e. LDL-C, 25 mg/dL; ApoB, 40 mg/dL; and non-HDL-C, 50 mg/dL.

American Diabetes Association. Cardiovascular Disease and Risk Management. Sec. 8. In Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(Suppl. 1):S60–71. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-S011.

Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, Blonde L, Bloomgarden ZT, Bush MA, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm - 2017 executive summary. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(2):207–38. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP161682.CS.

D'Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743–53. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579.

Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D’Agostino RB Sr, Gibbons R, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S49–73. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98.

Sabatine MS, Leiter LA, Wiviott SD, Giugliano RP, Deedwania P, De Ferrari GM, et al. Cardiovascular safety and efficacy of the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab in patients with and without diabetes and the effect of evolocumab on glycaemia and risk of new-onset diabetes: a prespecified analysis of the FOURIER randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Dec;5(12):941–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30313-3.

Sabatine MS, De Ferrari GM, Giugliano RP, Huber K, Lewis BS, Ferreira J, et al. Clinical benefit of evolocumab by severity and extent of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2018;138(8):756–66. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034309.

Bonaca MP, Nault P, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Pineda AL, Kanevsky E, et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering with evolocumab and outcomes in patients with peripheral artery disease: insights from the FOURIER trial (further cardiovascular outcomes research with PCSK9 inhibition in subjects with elevated risk). Circulation. 2018;137(4):338–50. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032235.

Charytan DM, Sabatine MS, Pedersen TR, Im K, Park JG, Pineda AL, et al. FOURIER steering committee and investigators efficacy and safety of evolocumab in chronic kidney disease in the FOURIER trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(23):2961–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.513.

Hwang YC, Ahn HY, Lee WJ, Park CY, Park SW. An equation to estimate the concentration of serum apolipoprotein B. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51607. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051607.

Masana L, Girona J, Ibarretxe D, Rodríguez-Calvo R, Rosales R, Vallvé JC, et al. Clinical and pathophysiological evidence supporting the safety of extremely low LDL levels-The zero-LDL hypothesis. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12(2):292–299.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2017.12.018.

Jones PH, Bays HE, Chaudhari U, Pordy R, Lorenzato C, Miller K, et al. Safety of alirocumab (a PCSK9 monoclonal antibody) from 14 randomized trials. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:1805–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.08.072.

Ray KK, Ginsberg HN, Davidson MH, Pordy R, Bessac L, Minini P, et al. Reductions in atherogenic lipids and major cardiovascular events: a pooled analysis of 10 ODYSSEY trials comparing alirocumab to control. Circulation. 2016;134:1931–43. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024604.

•• Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, Diaz R, et al. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097–107. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1801174. Landmark clinical trial demonstrating the effect of PCSK9 inhibitor, alirocumab, as add-on to background statin therapy in patient with ACS. After median 2.8 years-follow-up, LDL-C levels were 53.3 mg/dL in the alirocumab group and 101.4 mg/dL in the control-placebo group; an absolute reduction of 54.7%, and there were significant reduction in 5-point MACE by 24%, that translated to an absolute risk reduction (ARR) of 3.4%; CHD death by 28% (ARR 0.9 percent); CV death by 31% (ARR 1.3 percent) and all-cause death by 28% (ARR 1.7 percent). Components of non-fatal MI, fatal & non-fatal stroke, any CVD event, any CHD event, major CHD event, and all-cause death, were significantly reduced by 14%, 27%, 13%, 12%, 12% and 15%, respectively. ODYSSEY Outcomes was not designed or prespecified to evaluate a targeted LDL-C goal at the lowest level, but rather a dose-up and dose-down titration algorithm was utilized to achieve a narrow, limited treat-to-target LDL-C to 25–50 mg/dL goal range, permitting as low as 15 mg/dL, on the lowest alirocumab dose.

Steg PG, Szarek M, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, Brégeault MF, Dalby AJ, et al. Effect of alirocumab on mortality after acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2019;140(2):103–12. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038840.

Ray KK, Colhoun HM, Szarek M, Baccara-Dinet M, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, et al. Effects of alirocumab on cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes after acute coronary syndrome in patients with or without diabetes: a prespecified analysis of the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(8):618–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30158-5.

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.003.

Steinberg D. Earlier intervention in the management of hypercholesterolemia: what are we waiting for? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(8):627–9.

Kones R. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease: integration of new data, evolving views, revised goals, and role of rosuvastatin in management. A comprehensive survey. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2011;5:325–80. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S14934.

Robinson JG. Starting primary prevention earlier with statins. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(9):1437–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.076.

Robinson JG, Gidding SS. Curing atherosclerosis should be the next major cardiovascular prevention goal. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt A):2779–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.009.

Domanski MJ, Fuster V, Diaz-Mitoma F, Grundy S, Lloyd-Jones D, Mamdani M, et al. Next steps in primary prevention of coronary heart disease: rationale for and design of the ECAD trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(16):1828–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.857.

Jepsen AM, Langsted A, Varbo A, Bang LE, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. Increased remnant cholesterol explains part of residual risk of all-cause mortality in 5414 patients with ischemic heart disease. Clin Chem. 2016;62(4):593–604. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2015.253757.

Borow KM, Nelson JR, Mason RP. Biologic plausibility, cellular effects, and molecular mechanisms of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(1):357–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.07.035.

Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, Ketchum SB, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11–22. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1812792.

Tsimikas S. Lipoprotein(a): novel target and emergence of novel therapies to lower cardiovascular disease risk. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(2):157–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.000000000000023.

Burgess S, Ference BA, Staley JR, Freitag DF, Mason AM, Nielsen SF, et al. Association of LPA variants with risk of coronary disease and the implications for lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies: a Mendelian randomization analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(7):619–27. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1470.

Rosenblit PD. Extreme atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk recognition. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(8):61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1178-6.

Bohula EA, Morrow DA, Pedersen TR, Kanevsky E, Murphy SA, Giugliano RP, Sever PS, Keech AC, Sabatine MS. Atherothrombotic Risk Stratification and Magnitude of Benefit of Evolocumab in FOURIER. Circulation. 2017;136:A20183.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. Vanita R. Aroda for critical review, feedback, and edits of earlier and current drafts of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Paul D. Rosenblit received clinical trial research site funding from Amgen, Dexcom, GlaxoSmithKline, Ionis, Lilly, Mylan, and Novo Nordisk; speaker faculty honoraria from Akcea, Amgen, and Merck; and advisory board honoraria from Akcea, Esperion, and Novo Nordisk.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Macrovascular Complications in Diabetes

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosenblit, P.D. Lowering Targeted Atherogenic Lipoprotein Cholesterol Goals for Patients at “Extreme” ASCVD Risk. Curr Diab Rep 19, 146 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1246-y

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1246-y