Abstract

Purpose of Review

Online grocery shopping is increasingly popular, but the extent to which these food environments encourage healthy or unhealthy purchases is unclear. This review identifies studies assessing the healthiness of real-world online supermarkets and frameworks to support future efforts.

Recent Findings

A total of 18 studies were included and 17 assessed aspects of online supermarkets. Pricing and promotional strategies were commonly applied to unhealthy products, while nutrition labelling may not meet regulated requirements or support consumer decision-making. Few studies investigated the different and specific ways online supermarkets can influence consumers. One framework for comprehensively capturing the healthiness of online supermarkets was identified, particularly highlighting the various ways retailers can tailor the environment to target individuals.

Summary

Comprehensive assessments of online supermarkets can identify the potential to support or undermine healthy choices and dietary patterns. Common, validated instruments to facilitate consistent analysis and comparison are needed, particularly to investigate the new opportunities the online setting offers to influence consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death and burden of disease across the globe [1]. Sub-optimal diet is a leading risk factor, with over one-third of all deaths from cardiovascular disease in 2019, more than 6.8 million deaths in total, attributable to dietary risks [2]. Importantly, dietary risks are preventable [3]; improving population dietary intakes can lead to rapid reductions in the risk of cardiovascular and other diet-related diseases.

Retail food environments, particularly supermarkets, are influential in shaping dietary patterns [4] in both high-income and, increasingly, in low- and middle-income countries [5]. A retail food environment that is gaining in importance is online grocery stores, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In China and South Korea, online sales were estimated to make up around a quarter of all expenditure on groceries in 2020, with considerable increases on the previous year [6]. Between April 2020 and July 2021, on average the proportion of all food retail trade in the UK (excluding Northern Ireland) from online stores was approximately double that for the year preceding [7]. In Australia, recent reporting suggests that around a third of people have started shopping online for at least some their groceries since the pandemic began [8].

These shifts in shopping behaviour make it important to understand how online retail environments are designed and how different features embedded in online supermarkets may shape consumers’ purchasing patterns.

Comprehensive and standardised frameworks and instruments to evaluate food environments are important to understand and quantify key dimensions that influence consumer behaviour [9•]. Various methodologies and tools have been developed for physical (in-store) supermarkets [4, 9•, 10, 11]. These tend to evaluate the key food environment domains defined by the 4Ps of marketing, being Product (what is available?), Price (what is cheaper?), Placement (what is seen?) and Promotion (what is highlighted or incentivised?), since these retail characteristics shape consumer preferences and choices [4, 12, 13].

While the 4Ps are likely still relevant to online stores, there is significant potential for retailers to employ new and more subtle modes of influence, for example through activity tracking and personalisation. As such, previously developed methodologies for evaluating physical supermarkets may need to be revised to capture relevant aspects of these online settings.

This review aimed to systematically search for and report on studies investigating the healthiness of real-world online supermarkets and comprehensive frameworks or collections of instruments for assessing the healthiness of online supermarkets.

Methods

Search Strategy

A systematic search of peer-reviewed and grey literature was conducted to identify relevant literature. This was supplemented by a manual search of the reference lists of identified reviews and other relevant papers/reports and contact with experts in the field.

The following medical/health/allied health and multidisciplinary databases were searched:

-

EMBASE

-

PubMed

-

CINAHL

-

Cochrane Library

-

Scopus

-

Web of Science

Search terms were developed and refined to minimise irrelevant studies and ensure relevant papers previously identified were included. Terms incorporated various aspects to effectively and comprehensively capture the concepts “food retail”, “online retail” and “food environment”.

Grey literature was searched through a review of the first 100 results on Google and Google Scholar. The following databases were also searched for relevant material:

-

The World Cancer Research Fund’s NOURISHING database (https://policydatabase.wcrf.org/level_one?page=nourishing-level-one)

-

The International Network for Food and Obesity/Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) Research, Monitoring and Action Support (INFORMAS) network’s website (https://www.informas.org/)

-

The Centre for Research Excellence in Food Retail Environments for Health (RE-FRESH) network’s website (https://healthyfoodretail.com/)

Search strategies are available in supplementary material (Supp. Table 1). All searches were conducted between 22 and 28 June 2021.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they were cross-sectional descriptive studies that reported on assessments of the healthiness of real-world online supermarkets in relation to the 4Ps or other aspects of food environments that are determined by retailers (objective 1). Studies that described a comprehensive framework or set of instruments for assessing the healthiness of online supermarket environments were also included (objective 2).

Included studies were limited to real-world/natural settings to better represent implemented environments and for generalisability. Studies that assessed the healthiness of online supermarkets across settings (i.e. both supermarkets and other retail environments, e.g. food markets or convenience stores, both online supermarkets and physical stores) were included if results distinguished between settings. Studies were eligible if they were published after 1 January 2010 to ensure relevance to contemporary environments and features in this rapidly developing context. Original studies and reviews were eligible for inclusion and studies must have been available in English, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian or German. Reasons for exclusion were documented.

Screening and Selection of Articles

Duplicates were removed prior to screening. The titles and abstracts of references retrieved from searches were screened by a review author (DM) to identify papers/reports that potentially met the eligibility criteria. Full-text copies of potentially relevant sources were then retrieved and independently assessed by two review authors (DM, MM) to identify those that met the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus. A data extraction form, developed to collate data on study setting, design, findings and food environment domain assessed, was populated by one review author (DM).

Results

Study Selection

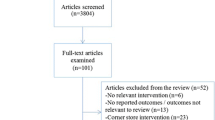

A total of 2519 references were retrieved from searches of peer-reviewed literature, with a further 86 records identified through grey literature and other sources. After removing duplicates, 1286 records underwent title and abstract screening. Of these, 203 full-text items were sought for further assessment against inclusion criteria. Finally, 18 studies were eligible for inclusion: 17 for objective 1 and one for objective 2. A flow-diagram of the search and selection process is included in supplementary material (Supp Fig. 1).

Studies Investigating the Healthiness of Online Supermarkets (Objective 1)

Seventeen papers detailing assessments of the healthiness of real-world online supermarkets were included in our analysis. Organised by the 4Ps, noting that some studies investigated multiple elements, 11 reported on prices, nine on products (predominantly availability of nutrition information) and five on promotions, with no papers reporting on placement. Twelve analysed data from the past 5 years (since 2016), with one paper not specifying the period of data collection. Almost all were conducted in high-income countries (n = 15, 88%; six in the UK, five in Australia, one each in New Zealand, Germany, Ireland and the USA), with an additional two (12%) studies in an upper-middle-income country (Brazil). No studies in lower-middle- or low-income countries were identified. Relevant characteristics of studies included under objective 1 are presented in Table 1.

Pricing

Several studies compared the costs of hypothetical diets and actual products. Two Australian studies found that a healthy diet was cheaper than a reference “typical” diet [17, 30], while others identified that healthier ready meals and unprocessed products were cheaper than their less healthy counterparts [18, 24].

A New Zealand study found that a basket of fruits and vegetables was cheaper from an online supermarket than physical supermarkets [23]. Two studies investigating the prevalence of price promotions on online supermarkets and consistency in pricing and price promotions between online and physical stores found that prices were similar across settings [14, 30]. However, in the Australian study, price promotions were infrequent overall (applied to 11% of products) and consistent across settings [30], while in the UK study, price promotions were more common but online stores were less likely to display them (24% online vs 32% in-store) [14]. Analysis of data from six online supermarkets in Scotland found that price promotions were less frequent than non-monetary promotions [20•].

Three studies found that unhealthy products were more likely to be price promoted than healthy foods. In Ireland, products high in fat, sugar and salt (as a category) were most commonly price promoted [16]. In Australia, one study found that unhealthy products were almost twice as likely to be discounted [27], with another finding that almost half of total beverage price promotions were for sugar-sweetened beverages [29]. Both also found that unhealthier products were most heavily discounted [27, 29]. Seasonal variation in the unhealthiness of price promoted products was also identified [16, 27]. An analysis of data from an online retailer in Germany identified that “psychological pricing”, where a price is set slightly lower than a round number (typically 9) to create a perception that a product is meaningfully lower in price and thus encourage purchase, was both common and most commonly applied to less healthy foods [19].

With regard to the types of price promotions, a study in Ireland and a study in Scotland both found that discounting was more common than multibuy promotions (where consumers are incentivised to buy additional products) overall [16, 20•]. However, two Australian studies found that multibuys were more commonly applied to unhealthy products [27, 29].

Products

The few available studies suggest that a large number of unhealthy products are typically provided in online supermarkets. In one UK study, around half of all products with declared nutrient content would be categorised as medium or high in total fats, total sugars and saturated fats, and almost a third would be categorised as medium or high in salt [21]. An Australian study identified that around two-thirds of total beverages available were sugary drinks and only one in five were plain waters or milks [29]. Two studies in Brazil found that three-fifths of products not exempt from regulations on nutrition labelling were classified as ultra-processed and a further fifth as processed [24, 25]; processed and ultra-processed products were less healthy on average [24] and ultra-processed products were the most common products passing in three of four nutrient profiling models used to target/enforce various food policies [25].

Several studies assessed the availability of nutrition information. Results differed widely, even within countries and across similar time periods. An analysis of three UK online supermarkets (period of data collection unknown but paper published in 2021) found that while two-thirds (69.8%) of products displayed some sort of front-of-pack nutrition label, just under half (48.0%) provided interpretive labelling (traffic light labelling), around a quarter (27.7%) displayed a nutrition information panel and 5.2% did not provide any nutrition information at all [21]. Another study of five UK online retailers (data collected July 2015) found that only one product (1%) did not provide the required nutrition information panel and that interpretive traffic light labelling was only present on approximately 41% of products [28]. A third UK-based study of six online supermarkets in March 2018 found that over three-quarters of product pages provided nutrition information (85.9%), with a similar proportion (80.9%) also providing information on ingredients [18]. Another study, analysing data from the same database (exact period of data collection unknown, but collection for the database commenced November 2017), reported that only 42% of products provided front-of-pack nutrition labelling of any type [14]. Two of these studies also compared products available online and in physical stores, identifying that products available online were less likely to provide front-of-pack nutrition labelling [14] and that online products generally featured fewer and/or less accessible nutrition labels [28].

Outside of the UK, a study in the USA reported that while a large majority of product pages do display nutrition and/or ingredient information, not all products which must provide nutrition information by regulation do so [22•].

While nutrition information may be available, the location of this information is also important and has been considered by two studies. In one UK study, nearly three-quarters of products only displayed nutrition information upon scrolling down a product page, while those retailers who did display nutrition information at first glance did not do so across all their products [28]. The USA study also found that information was mostly not presented immediately, with over half of products for which nutrition information was available presenting this on a different page [22•].

The two previously mentioned Brazilian studies also looked at health and nutrition claims. Almost a third of products displayed claims, with over two-thirds of products displaying claims ultra-processed, though products displaying claims were generally healthier than those not displaying claims [24]. Products displaying health/nutrient claims were more likely to pass three of the four nutrient profiling models applied to these products [25].

One study in the USA looked at the ability for users to customise online stores to suit their nutrition needs, identifying that products could be filtered by attributes such as fats or sugars content in half or fewer stores, respectively, and no stores offered the ability to order product listings by nutrition content [22•].

Two studies that compared products in online and physical stores, one in the UK [14] and one in Australia [30], found that product availability generally aligned across the settings.

Promotions

Only one study reported on the prevalence of promotions on online stores. A study in Scotland found that shoppers were exposed to over 500 promotions on each shopping occasion, on average, with non-monetary promotions more common than price promotions [20•]. Forty-six percent of all non-monetary promotions were products displayed when selecting products (on product pages and search results), with a further 37% found on a separate offers page.

Findings on the healthiness of promoted products differed. An Australian study found that unhealthy products were most commonly advertised [15] and a study from Northern Ireland found that products high in fat and sugar (as a category) formed the greatest proportion of promotions overall [26]. In this latter study, unhealthy products were most over-represented (33% of total promotions, compared to recommended 7% of intake), while fruits and vegetables were most under-represented (14% of promotions, compared to 33% of recommended intake) [26].

In the study of six online supermarkets in Scotland, only a fifth (21%) of promotions were for unhealthy products, most commonly crisps and confectionery, with an additional one-tenth (11%) of promotions for alcohol [20•]. As evidence of the sophisticated capacity of online retailers to tailor the displayed environment to users, the types of products being promoted differed in real-time according to whether a healthy or a standard basket of items was being selected. This study also found seasonal variation in the healthiness of promotions.

One Brazilian study, assessing the prevalence and messages of marketing techniques on products, found that almost half utilised some form of marketing [24]. 64.0% of total marketing techniques applied, including 66.1% of promotions of health/wellbeing and 56.4% of promotions of naturalness, were on ultra-processed products. Overall, however, products using promotional techniques had less total fats and saturated fats and more fibre.

Frameworks and Instruments for Assessing the Healthiness of Online Supermarkets (Objective 2)

While each of the studies included under objective 1 necessarily involves the use of some form of instrument for capturing and assessing an aspect of the retail food environment, none offered a comprehensive or consistent set that can be systematically applied in other studies. In addition, none sought to outline or describe the entire online supermarket environment, as the first step in developing a coherent set of readily applicable tools.

One additional paper providing a conceptual framework to comprehensively capture the healthiness of online retail food environments was identified (Khandpur et al. 2020 [31••]). The framework was developed through key informant interviews, literature reviews and pilot testing. An expert group, consisting of researchers and technical experts in online food retail, also participated in trial shopping exercises and discussions with authors to further refine the framework and assess content validity.

This framework aims to capture the entirety of the online retail environment’s influence on consumer behaviour. It incorporates attributes that are both common to physical settings, at least at a higher level, and specific to the online environment.

Domains outlined under this setting are classified as “dynamic”, signifying aspects of the environment that are determined to some extent by consumer-online system interaction, i.e. potentially modified by the retailer or the consumer themselves, or “static”, indicating attributes that are likely consistent for all users. The domains included are retailer policies and practices pre-shop (e.g. inventory management, website access) and post-shop (e.g. delivery, cancellations and orders) and consumer characteristics, preferences and past behaviours (static); and personalised marketing by retailers, marketing outside of the online store setting and consumer customisation of the website (dynamic). The framework also provides “cross-cutting” domains to capture equity and transparency in retailer policies and practices and the social, community and policy context in which online shopping develops and occurs.

The 4Ps are referenced under the domain “personalized marketing by retailers”, though the constructs outline different manifestations of the 4Ps in an online supermarket. This domain encompasses those mechanisms through which retailers adapt the online store environment to individual consumers, i.e. the immediate determinants of how the online supermarket environment looks and feels that can be manipulated by retailers to influence choices. Table 2 provides an overview of the elements included under this domain, as these were the focus of this review, as well as papers identified through this review that consider aspects of those attributes. Note that the studies are mapped according to the guidance provided by Khandpur et al., e.g. products promoted on separate special offers pages are included under “time-limited deals”, nutrition labelling is included under “point-of-purchase information” and products suggested after an earlier purchase under “cross-promotions” or “recommendations”.

Findings from our review also suggest that non-discounted prices (i.e. standard pricing in the absence of discounting or promotions), not clearly defined or captured through the above, may also be important [14, 17,18,19, 23, 24, 30]. Online store layout and navigation beyond the facets discussed above (e.g. placement on front, category and sub-category pages) may be another attribute worth investigating [20•, 32, 33].

Khandpur et al. did not provide, alongside the framework, a ready-made instrument that could be applied to consistently audit the healthiness of online retail environments. No results of application of the final framework against real-world supermarkets have been reported as yet.

Discussion

Practices applied in retail environments strongly influence purchasing and dietary patterns [4], and therefore have the potential to impact cardiovascular health [34, 35]. Our systematic review has highlighted that a small but growing number of studies are assessing the healthiness of certain aspects of online supermarkets, but overall the evidence remains limited. In addition, until recently, no systematic, overarching conceptual framework, identifying relevant practices that should be investigated further, has been available to guide consistent approaches to such assessments.

Despite the limited evidence, a number of interesting patterns have emerged based on the studies identified here. Price was the most regularly assessed online retail domain. However, while analysis of prices can inform assessments of the affordability of healthy and unhealthy products/diets, this is unlikely to be sufficient to suggest whether an online supermarket actually encourages their consumption. Some studies in the online setting have identified that a healthier diet may be cheaper than unhealthy diets/products [17, 23, 24, 30], but online supermarkets may undermine such intentions through misleading or deceptive pricing strategies [19], as commonly seen in physical supermarkets [36].

In relation to product placement and promotions, the advanced capability to disguise healthier products in this setting raises concerns. A number of studies identified through this review focussed on price and other promotions and advertising, which is an important avenue through which purchases and preferences are influenced. These suggest that promotions are largely skewed towards unhealthy products [15, 16, 20•, 24, 26, 27, 29]. This phenomenon is not unique to the online setting, however, with a recent review also finding that they were more frequently applied to less healthy products in physical supermarkets [37].

In addition, the focus on food labelling (basic nutrition information, interpretive nutrition labelling, ingredient and allergen information and health and nutrition claims) identified through this review [14, 18, 21, 22•, 24, 25, 28] is warranted, particularly as interpretive nutrition labelling has been shown to improve dietary choices [38, 39] but may be less common online than in physical stores [14, 28]. Our review suggests that the display of information online frequently does not meet mandated requirements for the same products in physical stores, or appear frequently enough to effectively support consumer decision-making, indicating that greater attention may need to be paid to updating regulation to account for these environments and/or monitoring compliance. The potential application of such labelling for marketing purposes, above encouraging informed and healthier choices, should also be closely monitored. Again, these issues are not restricted to online supermarkets; limited uptake of interpretive nutrition information on product packaging [40] and the use of health and nutrition claims on unhealthy products [41,42,43,44] is seen in physical supermarkets in countries where such labels may not be effectively regulated.

It is critical to comprehensively and, given their capacity to rapidly evolve, regularly investigate these environments. The studies reported here suggest ways to adapt existing and create new tools and protocols to examine these environments more closely; however, a coherent set of validated instruments to approach the task systematically and enable consistent analysis and comparison is needed.

The guiding framework described by Khandpur et al. is therefore an important and timely addition to the literature [31••]. Some of the elements in the framework align with the myriad auditing/assessment tools developed for use in physical retail environments [4, 9•, 10, 45,46,47,48]. This is clearly seen in the studies identified through this review, which largely applied or adapted existing methods for evaluating the 4Ps in physical stores.

However, the additional opportunities that the online environment introduces for retailers to manipulate consumer preferences and choices have been less well studied. The clear gaps in the literature, as shown in Table 2, may therefore also be due to a lack of frameworks and tools to capture the different ways that online supermarkets can influence choices. Though some papers identified here do consider some of these (placement of nutrition labelling [22•, 28], placement of promotions [20•], online store layout/navigation [20•], potential for user customisation [22•, 28]), studies to date have largely not uncovered any information specific to the online environment. This highlights the need for considerable methodological development.

Unfortunately, there have been only few investigations into the new ways that online supermarkets might influence consumer purchases and dietary patterns, particularly in the medical and health literature. One notable study tracking the information used by consumers shopping for groceries online found that site navigation was the most common method to identify relevant products, followed by searches and then pages displaying special offers [33]. Findings also suggest the importance of product photos and a lack of attention given to details such as nutrition information and other indicators of healthiness (traffic light labels, in this instance).

Another study, analysing data on nearly 200 million online transactions from a single UK retailer, provides some insight into aspects largely unique to the online setting [49]. Elements investigated included price sensitivity (selection of products from offers, deals and flash sales and after sorting products by price in ascending order) and “basket stability” (adding a product from a shopping list, favourites, suggested orders and previous orders) or “disrupted” activities (adding a product from searches or after engagement with offers and other features). Overall, few products in a shopping basket were added through price sensitive behaviours; of those products selected via a price sensitive mechanism, the vast majority were from special offers, which are more likely to be displayed prominently on the website. A majority of product selections were due to disrupted activities, predominantly searches.

A third useful study investigated the influence of “in-store displays” in an online supermarket, categorised as first screen, “aisle” (brand-level) and “shelf” (product-level) [32]. The authors found that these displays increased sales overall, with first screen displays more effective than aisle displays, which were more effective than shelf displays, i.e. products displayed before alternatives were available were more effectively promoted.

There is also some evidence to suggest that consumers’ use of mobile technologies (e.g. phone or tablet) for online shopping is associated with increased number of orders, and that consumers using mobile technologies are more likely to purchase habitual products [50].

Though automated online data collection methods are increasingly used and can be used to effectively and efficiently build a large dataset, they also have their limitations. While the routine collection of data from online supermarkets may be useful to describe some aspects that influence purchases and/or the healthiness of purchases (e.g. product nutrition information, price), or to investigate longitudinal changes in the same [18, 30], they may not capture all relevant information such as temporary promotions and product placement. Furthermore, automated methods largely capture elements that apply equally to online and physical stores, not those different features in the online setting that introduce new methods to influence consumers. In addition, it is evident that assessments of the overall online retail environment within a country should attempt to include as many retailers, within similar timeframes, as possible. Inconsistencies in such study design features likely underpin the wildly diverging findings on proportions of products displaying nutrition information observed across studies included in our review [14, 18, 21, 28].

Key strengths of our study include a comprehensive search for peer-reviewed and grey literature across a number of sources, including outside the medical and health research spheres. It also focussed on real-world settings in an attempt to understand these retail food environments as they actually exist and to improve generalisability.

However, there are some limitations to our review. All included studies but two were conducted in a small number of high-income countries, limiting the generalisability of our findings. Other avenues for consumers to purchase groceries online, for instance through convenience- or corner-type stores and via online food delivery services, are also likely to become increasingly common but were not considered here. In addition, the focus on real supermarkets has excluded the considerable number of studies, both observational and interventional, that have used simulated environments to understand elements of online supermarkets and strategies that may influence consumer choices.

Conclusions

The impact that the shift towards online grocery shopping will have on purchases, diets and health is currently unclear. However, our systematic review suggests that online supermarkets are already skewed towards promoting unhealthy products and, drawing on findings from the greater number of audits of physical stores, retailers are clearly willing to apply various strategies to encourage unhealthy choices. We have also identified that nutrition labelling in online retail environments is likely not sufficient to support informed consumer decision-making.

The online environment offers new and more covert methods to further the bias towards the promotion of unhealthy ultra-processed foods. As such, these environments must be closely monitored for the potential to direct consumers towards unhealthy products and diets, including a focus on identifying practices affecting or targeting vulnerable groups as a specific priority. There is also a need for further work to empirically identify and understand how consumer choices, and thus dietary patterns, nutrient intakes and health, are impacted by online retailing practices.

Paying heed to identified issues in measuring and comparing the healthiness and impact of food environments [9•], a comprehensive framework, such as that developed by Khandpur et al. [31••], provides a crucial reference point for future assessments of online supermarkets. Many of the studies identified in this review provide some insight into relevant aspects of that framework. However, more must be done in terms of developing validated and coherent tools to audit contemporary online supermarkets and consistently applying them to understand the various retailing and marketing practices involved. Studies which investigate the extent to which real-world online supermarkets preferentially apply these strategies to unhealthy products are then required to recognise, and act to improve, those settings which encourage unhealthy dietary patterns and increase the risk of diet-related disease.

The availability of a standardised but readily adaptable protocol (for example through the INFORMAS retail module, which aims to develop and apply common methods to monitor food environments across the world [51]) will be critical. This will support assessments in broader settings than those identified in this review, as online stores will continue to expand within and outside of high-income countries. Consistency in approaches will also allow comparisons between retailers and over time. Such efforts are essential to inform policy making, both by government and retailers, that supports healthier online supermarkets, improved dietary patterns and reduced risks of diet-related disease.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Roth GA, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):2982–3021.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, GBD compare. 2021, IHME, University of Washington: Seattle, WA.

GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators, Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet, 2019;393(10184):1958–1972.

Ni Mhurchu C, et al. Monitoring the availability of healthy and unhealthy foods and non-alcoholic beverages in community and consumer retail food environments globally. Obes Rev. 2013;14(Suppl 1):108–19.

Anand SS, et al. Food consumption and its impact on cardiovascular disease: importance of solutions focused on the globalized food system: a report from the workshop convened by the World Heart Federation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(14):1590–614.

Worldpanel K. Winning omnichannel: the future of FMCG and retail post-COVID. 2021, Kantar: London, UK.

Office for National Statistics, Retail Sales Index internet sales (20 August 2021). 2021, Office for National Statistics: Newport, Wales.

Australian Associated Press, Lockdown boom in online grocery shopping, in Australian Associated Press. 2021.

• Sacks G, Robinson E, Cameron AJ. Issues in measuring the healthiness of food environments and interpreting relationships with diet, obesity and related health outcomes. Curr Obes Rep. 2019;8(2):98–111. This review article clearly highlights the need for comprehensive and standardised frameworks and methods to monitor food environments and better understand their impact on diets and health outcomes.

Jaenke R, et al. Development and pilot of a tool to measure the healthiness of the in-store food environment. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(2):243–52.

Lytle L, Myers A. Measures registry user guide: food environment. Washington DC: National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research; 2017.

Kelly B, et al. Monitoring food and non-alcoholic beverage promotions to children. Obes Rev. 2013;14(S1):59–69.

Lee A, et al. Monitoring the price and affordability of foods and diets globally. Obes Rev. 2013;14(S1):82–95.

Bhatnagar P, et al. Are food and drink available in online and physical supermarkets the same? A comparison of product availability, price, price promotions and nutritional information. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(5):819–25.

Cameron AJ, et al. Do the foods advertised in Australian supermarket catalogues reflect national dietary guidelines? Health Promot Int. 2017;32(1):113–21.

Furey S. et al. What’s on offer? The types of food and drink on price promotion in retail outlets in the Republic of Ireland. SafeFood: Cork, Ireland. 2019.

Goulding T, Lindberg R, Russell CG. The affordability of a healthy and sustainable diet: an Australian case study. Nutr J. 2020;19(1).

Harrington RA, et al. Nutrient composition databases in the age of big data: FoodDB, a comprehensive, real-time database infrastructure. BMJ Open. 2019.

Hillen J. Psychological pricing in online food retail. Br Food J. 2021.

• Obesity Action Scotland. Survey of food and drink promotions in an online retail environment.Obes Act Scotland. 2021. This study of price and non-monetary promotions in online supermarkets in Scotland included some focus on unique aspects of the setting, such as placement of promotions and online store layout and navigation.

Ogundijo DA, Tas AA, Onarinde BA. An assessment of nutrition information on front of pack labels and healthiness of foods in the United Kingdom retail market. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–10.

• Olzenak K, et al. How online grocery stores support consumer nutrition information needs. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020;52(10):952–7. This study of the information made available in online supermarkets in the USA included a specific focus on placement of nutrition information by retailers and user ability to customise the environment or use nutrition attributes to identify products.

Pearson AL, et al. Obtaining fruit and vegetables for the lowest prices: pricing survey of different outlets and geographical analysis of competition effects. Plos One. 2014;9(3).

Pereira RC, de Angelis-Pereira MC, Carneiro JDS. Exploring claims and marketing techniques in Brazilian food labels. Br Food J. 2019;121(7):1550–64.

Pereira RC, Souza Carneiro JD, de Angelis Pereira MC. Evaluating nutrition quality of packaged foods carrying claims and marketing techniques in Brazil using four nutrient profile models. J Food Sci Technol. 2021.

Price RK, et al. What foods are Northern Ireland supermarkets promoting? A content analysis of supermarket online. 2017.

Riesenberg D, et al. Price promotions by food category and product healthiness in an Australian supermarket chain, 2017–2018. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1434–9.

Stones C. Online food nutrition labelling in the UK: how consistent are supermarkets in their presentation of nutrition labels online? Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(12):2175–84.

Zorbas C, et al. The frequency and magnitude of price-promoted beverages available for sale in Australian supermarkets. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2019;43(4):346–51.

Zorbas C, et al. Streamlined data-gathering techniques to estimate the price and affordability of healthy and unhealthy diets under different pricing scenarios. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(1):1–11.

•• Khandpur, N., et al., Supermarkets in cyberspace: a conceptual framework to capture the influence of online food retail environments on consumer behavior. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22). This is the first and, to date, only conceptual framework available which attempts to specifically and comprehensively capture those aspects of online retail food environments that influence consumer purchases.

Breugelmans E, Campo K. Effectiveness of in-store displays in a virtual store environment. J Retail. 2011;87(1):75–89.

Benn Y, et al. What information do consumers consider, and how do they look for it, when shopping for groceries online? Appetite. 2015;89:265–73.

Vadiveloo MK, et al. Contributions of food environments to dietary quality and cardiovascular disease risk. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2021;23(4):14.

Afshin A, et al. CVD prevention through policy: a review of mass media, food/menu labeling, taxation/subsidies, built environment, school procurement, worksite wellness, and marketing standards to improve diet. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(11):98.

Gertner D, et al. Calories and cents:customer value and the fight against obesity. Soc Mark Q. 2016;22(4):325–39.

Bennett R, et al. Prevalence of healthy and unhealthy food and beverage price promotions and their potential influence on shopper purchasing behaviour: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2020;21(1):e12948.

Croker H, et al. Front of pack nutritional labelling schemes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent evidence relating to objectively measured consumption and purchasing. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2020;33(4):518–37.

El-Abbadi NH, et al. Nutrient profiling systems, front of pack labeling, and consumer behavior. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2020;22(8):36.

Jones A, et al. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling to promote healthier diets: current practice and opportunities to strengthen regulation worldwide. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(6):e001882.

Kaur A, et al. The nutritional quality of foods carrying health-related claims in Germany, The Netherlands, Spain, Slovenia and the United Kingdom. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(12):1388–95.

Kaur A, et al. How many foods in the UK carry health and nutrition claims, and are they healthier than those that do not? Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(6):988–97.

Franco-Arellano B, et al. Examining the nutritional quality of Canadian packaged foods and beverages with and without nutrition claims. Nutrients. 2018;10(7).

Pulker CE, Scott JA, Pollard CM. Ultra-processed family foods in Australia: nutrition claims, health claims and marketing techniques. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(1):38–48.

Borges CA, Gabe KT, Jaime PC. Consumer food environment healthiness score: development, validation, and testing between different types of food retailers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3690.

Vandevijvere S, et al. Towards healthier supermarkets: a national study of in-store food availability, prominence and promotions in New Zealand. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72(7):971–8.

Harmer G, et al. Capturing the healthfulness of the in-store environments of United Kingdom supermarket stores over 5 months (January–May 2019). Am J Prevent Med. 2021.

Sacks G, SS, Grigsby-Duffy L, Robinson E, Orellana L, Marshall J, Cameron AJ. Inside our supermarkets: assessment of the healthiness of Australian supermarkets, Australia 2020. Deakin University: Melbourne. 2020.

Munson J, Tiropanis T, Lowe M. Online grocery shopping: identifying change in consumption practices. 2017.

Wang RJ-H, Malthouse EC, Krishnamurthi L. On the go: how mobile shopping affects customer purchase behavior. J Retail. 2015;91(2):217–34.

Swinburn B, et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev. 2013;14(S1):1–12.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Nutrition

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maganja, D., Miller, M., Trieu, K. et al. Evidence Gaps in Assessments of the Healthiness of Online Supermarkets Highlight the Need for New Monitoring Tools: a Systematic Review. Curr Atheroscler Rep 24, 215–233 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-022-01004-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-022-01004-y