Abstract

Coastal protection comprises shoreline preservation and stabilisation as well as flood protection. Besides these technical aspects, coastal protection also represents a genuine social endeavour. Within this interplay of technical and social dimensions, planning and acting for the safety of people and assets along the coastline has become increasingly difficult for the responsible authorities. Within this context, Nature-based Solutions (NbS) for coastal protection offer a promising addition to and adaptation for existing protection measures such as dikes, sea walls or groynes. They bear the potential to adapt to shifting boundary conditions caused by climate change and cater the growing social call for sustainable solutions that benefit water, nature and people alike. This paper analyses, how NbS can fit into the entangled and historically grown system of coastal protection. As a paradigmatic example, the German islands of Amrum and Föhr were chosen. To contextualise the topic, a brief recap of the formation of these North Frisian Islands and their social history regarding coastal protection is given. This will be followed by a review of the relevant literature on the development of coastal protection on the two islands including its historical development. Using the theory of Social Representations (SRs), these historical insights are analytically contrasted with a synchronic snapshot gained from stakeholder interviews about the assessment of protective measures, and their anticipated future development with regard to the possible feasibility and implementation of NbS. This analysis reveals that, historically and synchronically seen, coastal protection on both islands is rather characterised by a dynamic rationale and the constant testing of and experimenting with different measures and concepts. However, well-established measures like diking or the construction of brushwood groynes for foreland creation are not being questioned while new approaches running against this rationale such as NbS are in many cases initially met with scepticism and doubt. Out of this follows that past and present dynamics in coastal protection play a vital role in planning. Hence, the implementation of NbS as signposts for the future requires an integrated and balanced interdisciplinary approach that considers the socio-technical dimensions of coastal protection for future coastal adaptation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coastal protection encompasses the preservation of coastlines through erosion protection on the one hand, and flood protection on the other hand. On the mainland coast as well as on islands, coastal protection has traditionally been an engineering discipline whose rationale was and still is characterised by a constant process of change, re-evaluation and evolution. On the North Sea coast, for example, first settlers were ostensibly exposed to the dangers of storm surges from the North Sea without any protection (cf. Brandt 1992, Knottnerus 2005). To be able to sustain a living under these harsh conditions, they needed to adapt to the coastal environment. Consequently, people along the coast developed measures and structures – nowadays called coastal protection – to protect their lives, their goods as well as their chattels from the floods (cf. Fig. 2), resulting a purely reactive process based on trial and error (Küster 2015). It was not until the 11th or 12th century that collaborative measures of coastal protection began to take hold and spread (Bijker 1996).

Nowadays, in most countries of the North Sea Region (NSR), the state is responsible for the protection of its citizens against the dangers of the sea and has mainly taken over the task of coastal protection or coordinates the work in an advisory capacity (Jordan et al. 2019). Within this work to be performed, concepts of coastal protection are actually conceived as to be constantly re-evaluated while preventive measures intend to anticipate possible future storm surges to prevent damage to life and livelihoods behind the dike (e.g. FAIR 2020). Planning in a socially and economically sound way while making the right decisions is more difficult than ever for those in charge of coastal protection. On the one hand, recent societal and scientific changes shifted the spotlight and political will to multifunctional concepts which address protective as well as natural and social issues on the coast. On the other hand, knowing that climate change will affect coastal safety (IPCC 2019), but being uncertain to which degree, makes it tough to take appropriate and socially acceptable choices, especially on a local level.

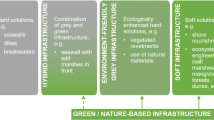

This multitude of societal, technical and natural developments call for adaptive solutions, which, in addition to existing and well-functioning coastal protection, frame coastal ecosystems as entities which are to be protected. Solutions are needed that benefit Water, Nature and People. These aspects are covered under the umbrella term of Nature-based Solutions (NbS). Especially in the last decade, numerous studies (e.g. Borsje et al. 2011, Jordan and Fröhle 2022, Morris et al. 2018, Schoonees et al. 2019, Sutton-Grier et al. 2019) as well as reports and strategy papers (e.g. Bridges et al.2019, European Commission 2019, Cohen-Shacham et al. 2016, MELUR 2015, Rabe et al. 2018) have focused on the newly emerging field of NbS in coastal protection. The question, however, remains how these soft and interactive measures fit into the general rationale of coastal protection which is based on the idea of defence or resistance as expressed by dike structures (cf. Holzhausen and Grecksch 2018) or walls which are not only confronting, but also have to get bigger, wider and more massive within the context of a materialising climate change? Furthermore, if one looks more closely at the history of coastal protection in the NSR, it becomes apparent that dikes have been just one - though prominent - measure to protect the coast while other ways of doing coastal protection, such as the protection and development of dunes (e.g. Müller and Fischer1937a, Sørensen et al. 1996, Reise and MacLean 2018), the creation of salt marshes in the dike foreland (e.g. Müller and Fischer 1937b, Vriend 2014) or working with sand in the coastal foreshore or on the beach (e.g. Niemeyer et al. 1996, Wiegel and Saville 1996), existed as well. All these measures have been applied and executed in part for decades or even centuries as a supplement to so-called ‘hard’ coastal protection which indicates that the so-called path dependency of diking as the only measure for coastal protection does not exist.

Within the scope of this paper the interplay, as illustrated above, is analysed from a place-based and socially oriented perspective because coastal protection basically is a local endeavour protecting local communities. As a case-study it addresses the developments on the German islands of Amrum and Föhr situated in the North Frisian Wadden Sea from a diachronic and synchronic angle, with the aim to reveal the various rationales of doing coastal protection. The paper starts with an introduction into the formation of the natural landscape and provides an impressionistic insight into the social history of the region. Following the theoretical and methodological approach, a descriptive literature review on the development of coastal protection on the two islands will provide a diachronic insight into the various and sometimes shifting concepts and developments of coastal protection. These insights will be contrasted with a synchronic snapshot about the assessment of protective measures, as well as their current and anticipated future development with regard to the possible feasibility and implementation of NbS, gained from stakeholder interviews and systematised with the help of the theory of social representations. These insights will assist in answering the following three interconnected research questions:

-

1.

Is the history of protecting the islands against the sea characterised by a rigid and confronting rationale or can a more dynamic rationale be disclosed that displays a more experimental evolution of coastal protection?

-

2.

In what way and to what extent is the prevailing rationale of coastal protection anchored in the minds of the people and what role do past experiences and memories play in the present?

-

3.

What role can the analysis undertaken here play in the context of future coastal adaptation with regard to NbS?

Formation and social history of the North Frisian Wadden sea landscape

The Wadden Sea extends in front of the entire German Bight, stretching from the northern Netherlands along the German coast up to the south-western tip of Denmark (see Fig. 1, left). The islands of Amrum and Föhr, belonging to the North Frisian Islands, are located in the North Frisian Wadden Sea in front of the west coast of the German federal state of Schleswig-Holstein (see Fig. 1, right).

Geologically speaking, the formation of the North Sea, as the entire North European region, is shaped by past ice ages and glacial deposits. The extent of the North Sea which we see today is a result of the developments after the last ice age. The still dry area of the North Sea Basin, a comparatively flat pleistocene land surface, was flooded by the water released from the ice (Stadelmann 2008). In the postglacial climate the ice was melting quickly causing a corresponding rise in sea level - between 7,000 and 5,000 B.C. on average 1.25 m per century (Behre 2008). After the initially rapid rise in sea level it declined to such an extent that it allowed the relocation of sediments in the area of today’s Wadden Sea so that the first wadden areas developed (MELUR 2015).

The origin of the Wadden Sea can hence be dated back some 4,000 years ago, when the rate of sedimentation exceeded sea level rise. Consequently, the formation of the Wadden Sea and the marshland belt began which was triggered through the deposition of finest sediments as well as organic material (Stadelmann 2008). The reclamation of more and more land from the North Sea in combination with extensive peat cutting, which was performed by coastal inhabitants and weakened the vastly extended marshlands, allowed severe storm surges to break through the outer belt, slowly ripping the landscape apart (Stadelmann 2008). Here, the two storm surges of 1362 and 1634 - the first and the second ‘Grote Mandränke’ - marked special recesses and caused disastrous land losses which could not be compensated for. Thus, these single disastrous events, in combination with a mass of light and medium storm surges that have occurred over the centuries (Rheinheimer 2003), ultimately formed the North Frisian Holms and Islands, among them Amrum and Föhr (Thorenz 2014). The last devastating storm surge in 1634 completed the series of major land losses in the Wadden Sea although other storm tides followed but did not have comparative impacts on the landscape.

Against the background of this natural history, the socio-historical perspective on coastal protection in North Frisia is to a considerable content based on the dictum ‘God created the sea, the Frisians the coast’. This motto refers to those who have fought against the waters coming from the sea, created and maintained the though shifting coastline as it exists today and who were and are in charge of coastal protection. Furthermore, and as Allemeyer (2006) and Jakubowski-Tiessen (1992) have shown, diking and coastal protection should always be conceived a part and parcel of a wider social and - sometimes - historical context in which certain social, political, scientific or even religious aspects play a vital role. Dikes were means to tame the sometimes uncontrollable character of the sea while they also offered the possibility to change or partly control the living conditions of those settling in the marshes (Panten 1992; Steensen 2020). Furthermore, dikes became and still are a dividing line between the wild and uncultivated sea or nature ‘out there’ beyond the dike and the cultivated land landward of the dike (Knottnerus 2021). But they are more, they are regulating devices that contribute to forming and structuring social systems as their maintenance requires a certain degree of social organisation, coherence and institutionalisation which regulated and still organise parts of everyday life in North Frisia (Knottnerus 1992; 1996).

The fear of the sea and its storm surges represents one of the basic fears and risks in North Frisia in the 18th century, instigated an innovation boost during which techniques of building dikes were considerably improved, (cf. Fig. 2), leading to standardisation based on empirical and measured observations. This development was accompanied by the development of social security systems which indicate a change in regional cohesion on the one hand and a shift in the prevailing mentality on the other hand: religious interpretations of disasters as willed by god were in a way superseded by preventative human actions taming the consequences of such events (Allemeyer 2006). Nonetheless, both rationales stand side by side and characterise this transitional period.

Development of dike design and construction – dike cross sections from the 13th century until today for different locations along the North Sea coast of Schleswig-Holstein. Scale of dike width below in metres; references: (1) Hofstede (2019a), (2) Kramer (1989), (3) Kramer (1992), (4) LKN.SH (2016), (5) Scherenberg and Rohde (1992)

Historically seen, these developments led to mottos such as the aforementioned ‘God created the sea, the Frisians the coast’ or the image of the ‘free Frisian’ which also refers amongst others to the constant fight of the local population with and against the ‘Blanke Hans’ (Rieken 2005, Rheinheimer 2003). Research revealing the regional and local sense of place or “Heimat” (cf. Ratter and Sobiech 2011, Ratter and Gee 2012, Ratter and Philipp 2015, Döring and Ratter 2015, Döring and Ratter 2018, Döring and Ratter 2021) shows that even nowadays a deep relationship between the coastal landscape and its inhabitants, specified in terms of the aforementioned mottos and images, exists.

Today, the region of North Frisia copes with demographic change, a declining agricultural sector and a practically no-longer-existing shipping and fishing industry. The wind energy sector, however, represents a promising area for safeguarding jobs while the whole region economically relies on tourism. Furthermore, aspects of climate change and coastal protection represent current challenges to be managed in the near future as the land behind the dikes often lies below sea-level (Reise 2015; Hofstede 2019b). This has been outlined in the governmental strategy for coastal protection (MELUND 2022) that assesses the state of the art of dikes and develops adaptation measures to be taken for a safe future on the mainland and the islands. Comparable aspects have also been addressed in the so-called Strategy for the Wadden Sea 2100 (MELUR 2015) representing a cooperative effort to manage and protect the North Frisian Wadden Sea Coast with the national park from possible impacts of climate change (Hofstede and Stock 2018). For the islands specifically, different reports have been published that assess and aim at improving the current state of the art of protection and adaptation measures against climatic change (e.g. Klimaschutzkonzept Helgoland 2013, MELUR 2014). All these activities are locally negotiated, administratively supported and politically endorsed as outlined in the Climate Protection Concept North Frisia (Wagner et al. 2011).

In summary, the district of North Frisia, including the islands, represents a coastal area which was and is deeply marked by its history of diking and storm surges. It displays many characteristics and problems typical for coastal regions and currently prepares to engage and cope on various social, administrative and technical levels with the anticipated risks of an impending climate change.

Theory and method: social representations and coastal protection

To analyse the varying rationales of coastal protection in this paper, the theory of social representations (SRs) first formulated by Moscovici (1961, 1988, 2000) was used, as it provides an interdisciplinary applicable and methodologically viable way for studying and analysing how those involved in the context of coastal protection produce diverging or converging representations of it and discuss, negotiate and contest underlying issues and values. Moscovici defined SRs as

‘[...] a system of values, ideas and practices with a twofold function: first, to establish an order which will enable individuals to orientate themselves in their material and social world and to master it; and secondly to enable communication to take place among members of a community by providing them with a code for social exchange and a code for naming and classifying unambiguously the various aspects of their world and their individual group history.’ (Moscovici 1973)

Generally seen, the advantage of the theory of SRs conceptually consists in the fact that it helps to specify and study a variety of communicative mechanisms and social processes that assist in forming commonly shared or contested representations of a certain issue. This can, for example, be seen in the present case as living in the district of North Frisia is characterised by the fact that coastal dwellers are more or less directly engaged in current issues of coastal protection. The motto ‘God created the sea, the Frisians the coast’ – as already indicated in “Formation and social history of the North Frisian Wadden sea landscape” - reflects a self-attributed identity, forms a relation to the coastal landscape and subcutaneous values bound up with it that contribute to developing meaning systems which enable or hinder communication among those involved in the issue of coastal protection.

One has to be aware, however, that SRs do not develop out of the blue as their emergence requires a sufficiently relevant issue for a community or social group to initiate negotiation, debate or even a conflicting discourse. The example discussed in this work of changing the rationale of coastal protection in the probable direction of NbS is such a case. It was gradually introduced during various research projects (e.g. MELUND 2021, Fröhlich and Rösner 2015) and publications (e.g. Reise 2015) in the recent years and created a critical assessment among the group of the interview partners. Importantly though, the present communication about the implementation of NbS is now and again rendered against the SR of past ways of doing coastal protection which displays a ‘peculiar power and clarity of [social] representations [...] with which [...] the reality of today [is assessed] through that of yesterday’ (Moscovici 1984). This so-called process of cultivating an issue or topic, as based on a backward reasoning, can be seen in the fact that references to the history of diking on the North Frisian islands pervade the interviews conducted and contribute to setting a conceptual background against which the current issue of NbS is assessed: the long-lasting ways of doing coastal protection is often depicted as the right and apparently successful way while a change of doing it in terms of NbS is in many cases experienced as challenging or even difficult within the current social, scientific, political and institutional rationale. Additionally, this process could be characterised by mechanisms of anchoring which contribute to making the new or unfamiliar known by integrating it into a pre-existing structure of SRs. Thematic anchors provide a big or overarching picture for example between nature and culture via the use of antinomies such as the opposition between coastal and nature protection, and transfer them further on into constitutive paradigms such as ‘the fight against the water’ or ‘providing space for water and nature’. These processes of anchoring are complemented by the mechanism of objectification which makes the unknown graspable by transforming something abstract into something concrete. Here, a new or abstract phenomenon such as climate change is rendered concrete by linking it to perceivable meteorological events or by using scientific results developing a network of experiences and knowledge(s) many people can relate to. This ‘network of ideas [is] [...] more or less loosely tied together’ (Moscovici 2000) by metaphors, images, facts, values, assessments as it unfolds when new ways of doing coastal protection enter the discursive arena.

In summary, one can say that individuals achieve SRs not exclusively by thinking, contemplating or personal experience, but also by actively taking part in societal discourses and social conflicts. ‘Social representations play an important epistemological [and pragmatic] role in communication’ (Wagner 2012) forming collective meaning systems that corroborate or differ from traditional views on and acting about certain issues.

To zoom in on the analysis, insights gathered through a systematic in-depth reading and content oriented analysis of available written sources (Scientific research, project reports, political and administrative documents, and newspaper articles) led to a combined historical-qualitative approach, as it holds the potential to disclose the somewhat diachronic patterns of interpretation and SRs pervading past, current and future-oriented mind-sets of coastal protection presently at work (Creswell and Creswell 2018). The next methodological step consisted in the search and analysis of historical sources about measures of coastal protection on Amrum and Föhr. The historical analyses at hand in the seminal works by Müller and Fischer (1937a, 1937b) and Stadelmann (2008) were used as these publications offered a saturated and descriptive insight into the past developments of coastal protection on both islands. The historical information gathered from them was visualised to give an overview over the variety of protective measures taken since the 15th century (cf. “Evolution of coastal protection on Amrum and Föhr”).

Against this historical background, semi-structured interviews with 14 actors deeply engaged in coastal protection in North Frisia were conducted. A semi-structured questionnaire was developed by the first two authors of this paper, critically inspected, revised by all four authors and re-revised after three initial interviews were conducted. Structurally, all interviews began with questions addressing the sense of place (Casey 1997; Malpas 1999) or home (Ratter and Gee 2012) to emotionally and thematically emplace the interviewee and the interviewers. This introductory section was followed by

-

queries revolving around the work context of the person interviewed,

-

the individual framing and assessment of climate change and its relevance for the local and regional level (Döring and Ratter 2018),

-

an interrogation about the current state of the art of coastal protection in North Frisia in times of a looming climate change and

-

the relevance of NbS in this context.

The interview ended with an envisioning exercise where interviewees were asked to imagine the future development of North Frisian Islands within the period of the next 50-100 years against the background of a coming climate change. Interviews lasted between 45 minutes and 1.5 hours, were conducted in places chosen by the interviewees, transcribed verbatim and cooperatively analysed by the first two authors of this paper. Once central themes or topics emerged during the investigation, segments of the interview transcriptions were individually grouped in categories. These bottom-up categories were refined and reformulated in the course of the interview analysis with regard to assessing their general meaning, analytical plausibility and empirical relevance for the present paper. This procedure contributed to calibrating the coding of interviews (Saldaña 2015) resulting in a corroborated set of 23 empirical categories (see Appendix for an overview). A final step consisted in selecting those SRs which analytically and empirically appeared to be of relevance for tackling the research questions discussed in this paper. Each of the four categories selected was re-analysed with regard to its past, present and future-related visions and reflections about how the coast was, is and should be protected. This displayed a range of interconnected and sometimes opposing experiences and ideas which, besides the well-established rational of diking, brought about ideas and possibilities of how coastal protection can be done differently (cf. “Stakeholders’ perspectives on historical, present and future dynamics in coastal protection”).

Evolution of coastal protection on Amrum and Föhr

In the following, the evolution of coastal protection will be described for both islands from the poorly documented beginnings in the 15th century until the end of the 20th century, marking the beginnings of the preparations for the current status quo with the so-called ‘Generalplan Küstenschutz - integriertes Küstenschutzmanagement in Schleswig-Holstein’ (MELUR 2012; MELUND 2022), the new General Plan for Coastal Protection. In order to provide a concise overview over the abundance of measures implemented per century and location, the most relevant events, documented projects and measures relating to coastal protection have been divided into the categories (cf. Figs. 5 and 8)

-

Storm Surge with Consequences,

-

Administration and Decrees,

-

Grey Measures (hard structures, e.g. dikes and sea walls),

-

Green Measures (soft measures, e.g. nourishments and plantings),

-

and Hybrid Measures (hard structures using or supporting natural processes, e.g. groynes).

Storm surges display key events and experiences, which can mark the the beginnings of new eras in coastal protection. Through damages to existing coastal defences, storm surges represent a directly visible influence that help to drive development and are therefore included in the following compilation. However, major man-made infrastructure developments in the respective region may also influence the dynamics of currents or sedimentary processes. They are therefore also of importance for coastal protection and its evolution and shall thus be mentioned here briefly. Harbour constructions, which took place on Amrum in the 20th century (Stadelmann 2008) and even began on Föhr in the early 20th century (Müller and Fischer 1937b), can influence the local sedimentation and erosion processes. Harbour construction measures that also serve protective purposes, such as seawalls or groynes, are included in the following. Other developments that could also influence the conditions am Amrum and Föhr are large-scale coastal protection projects in the region, like the sand nourishments on Sylt which have been carried out regularly since 1972 (Führböter and Dette 1992; Staudt et al. 2021), or major infrastructure projects like the construction of the Hindenburgdamm in 1927, connecting the neighbouring island of Sylt with the mainland and thus interrupting the tidal current in the northern North Frisian Wadden Sea area. In addition, large-scale land reclamation in the region, which continued well into the 20th century, can affect conditions on the islands. So-called Köge (polder) were originally built to gain arable land, e.g. the Gotteskoog as one of the biggest and earliest in 1566 (Meier 2011). During the 20th century, smaller areas like the Tümlauer Koog (1935) or the Norderheverkoog (1936) were reclaimed from the sea in order to build new settlements. More recent projects such as the Hauke-Haien-Koog (1960) or the Beltringharder Koog (1987) primarily served coastal protection or water management purposes (Kunz and Panten 1999; Stadelmann 2008). As a last influential factor, the development of tideways is to be mentioned. The tideways around the islands - Norderaue, Süderaue or the Amrum Tief - are constantly changing, whether through natural processes or anthropogenic interventions. These can include single events like e.g. the sand extraction in the Norderaue for nourishments on Föhr between 1975 and 1982, whereupon the tideway experienced more erosion and shifted to the north (LKN.SH 2019), or constant maintenance works in the tideways to guarantee a tide-independent shipping traffic.

As stated at the outset, in contrast to the damages caused by a storm surge, the influences of these man-made infrastructure developments cannot be attributed as clearly to changes on the islands and are not located directly on the islands but in the wider surroundings or the region. As the following analysis is limited to the measures implemented directly on the islands, the developments or events briefly described here are neglected hereafter.

Amrum

The history of documented works on coastal protection on the island of Amrum dates back to the end of the 17th century, when the era of passive and active dune management began. Several decrees and regulations regarding the protection of the dunes were issued in the 18th century (cf. Fig. 5). At the time, the reason for this measure consisted not primarily in doing coastal protection, but was rather motivated by the inhibition of windblown sand to protect the farmland and settlements to the east of the dunes. Hence, the importance and the influence of the natural habitats present on the island was recognised early on and certain measures to shape these natural environments were taken-up to push nature and natural processes towards a desired outcome for the islanders. As a result of the land division as introduced in 1800, dune protection work was placed under authority supervision, marking the beginning of the institutionalisation of coastal protection works. From the beginning of the 19th century, stalks were actively planted repeatedly to prevent the island from sanding up. Furthermore, between 1887 and 1898, afforestation of the heath areas between the dunes and meadows began in order to further contain the drifting of sand onto the eastern side of the island (Müller and Fischer 1937a).

The storm surge in February 1825 caused a dune breach near Risum in the north-west of the island, henceforth known as Risumlücke (Fig. 3 - Risum Gap). After first attempts of naturally redeveloping the dunes through enhanced sand deposition caused by stalk plantings and wooden, sand-trapping fences between 1865 and 1869, the authorities in charge decided to soften the impacts from the sea on the younger foredunes. Furthermore, at the end of the 19th century, between 1894 and 1899, several stone groynes and wooden groynes were built to protect the Risumlücke which were the first of this kind on Amrum (Müller and Fischer 1937a).

Evolution of the coastal protection at Risum (enlarged detail from Fig. 5, section rotated in clockwise direction for display purposes, north arrow below the shape of the island indicates cardinal directions). Display of the most important coastal protection related measures and events documented in Müller and Fischer (1937a) and Stadelmann (2008). Measures or events mentioned in the text are marked in the figure giving the year and a keyword

In the 20th century dune conservation and maintenance remained of great importance, and stalk planting as well as the afforestation of heath areas was continued with interruptions through two world wars. At the same time, the first half of the 20th century marks the beginning of grey or hard coastal protection measures such as dams, sea walls or dikes. In 1914, both a dam in the Risumlücke (see Fig. 3) and a sea wall off Wittdün (see Fig. 4) were built, since previous efforts did not result in the desired long-term protection. Grey measures, such as the Risum dam, did not replace green techniques and approaches from before, but were rather constructed to work and function together. The overall approach to tackle coastal protection issues was thus very much problem-oriented, pragmatic and relied on combinations of proven and new techniques and ideas (Müller and Fischer 1937a).

Evolution of the coastal protection at Wittdün (enlarged detail from Fig. 5, section rotated in anti-clockwise direction for display purposes, north arrow below the shape of the island indicates cardinal directions). Display of the most important coastal protection related measures and events documented in Müller and Fischer (1937a) and Stadelmann (2008). Measures or events mentioned in the text are marked in the figure giving the year and a keyword

The seawall at Wittdün was continuously extended and strengthened in the years following its construction in 1914, partly after having been severely damaged by several storm surges. A foot protection was added and increased fortification was created by groynes in front of the sea wall. After the storm surge in October 1936, the seawall had to be restored again and a revetment of asphalt was added for additional protection and weighting at the foot of the wall (Müller and Fischer 1937a). Besides the developments in Wittdün and Risum, diking was introduced on Amrum in the first half of the 20th century. After completion in 1934 and 1935 respectively, first official dike inspections were held in the Norddorfer Marsch (marshland between Norddorf and the dunes at Amrum Odde) in 1935 and the Wittdüner Marsch (marshland between Wittdün and Steenodde) in 1936 (Müller and Fischer 1937a).

In the second half of the 20th century, the construction of grey, hard coastal protection continued to progress. At the same time, however, working with sand using natural distribution processes was beginning to get some recognition. In dune management, the focus of maintenance work was primarily on the areas at the northern and southern end of the Kniepsand. Hence, there was never only one concept or rationale of coastal protection, but always a variety if not explicit diversity of approaches best-suited for respective locations. The authorities responsible, as one can see, always kept on learning more about the natural environment and how to interact with it, developing coastal protection accordingly, using hybrid measures, and combining grey and green coastal protection.

The severe storm surge in 1962, which accounted overall for massive damages and claimed many lives on the mainland, caused a dike breach over a length of 300 m at Norddorfer Marsch and a smaller breach over 75 m at Wittdüner Marsch. Both dikes were repaired and, in case of the dike at Norddorfer Marsch, improved and strengthened in the same year. After renovations to the sea wall following a storm surge damage in the autumn of 1973, a sand nourishment was carried out for the first time to further protect the wall after the 1976 storm surge (Stadelmann 2008). Again, a new approach was followed and tried out, combining proven and new techniques in order to advance coastal protection.

The evolution of coastal protection, different strategies, structures, concepts and regulations on Amrum in interaction with damaging flood events over the past centuries as described above, are summarised and depicted in Fig. 5.

Evolution of the coastal protection on the island of Amrum. Display of the most important coastal protection related measures and events documented in Müller and Fischer (1937a) and Stadelmann (2008). Starting with the ring in the middle, each of the light grey rings represents a century; from inside to outside, the 17th, 18th, 19th, 20th (first half) and 20th (second half) century. Measures and events are divided into five categories (see legend) and shown as coloured ring segments in the figure according to their respective century and location on Amrum. The thickness of the ring segments indicates the combined number of entries of the same category at this location (see legend). The sequence of the ring segments from the inside to the outside represents the chronological sequence in this century for each location in a simplified way

Föhr

The evolution of coastal protection on Föhr is closely linked to its institutional history. Until 1864 the island was administratively separated into an East and West part, with the border splitting it almost in half and running from north to south through the village of Nieblum. The separation influenced the various developments in Osterlandföhr, which belonged to the duchy of Schleswig, and Westerlandföhr, which was part of the Kingdom of Denmark.

In contrast to the situation on Amrum, the inhabitants of Föhr had no dune as a natural barrier against the sea and, therefore, could not purely rely on and work with natural forces for protecting the island against the incoming sea. Man-made technical coastal protection was therefore much earlier of much more importance than on the neighbouring island. In the 15th century, to whence solid documentation of coastal protection on Föhr dates back, houses in the eastern and western marsh of Föhr were built on dwelling mounds. Only a few areas were secured by so-called summer dikes, built by the farmers to protect their lands from minor floods during the summer months. By the end of the century in 1492, the first documented, coherent dike was completed. For the most part, however, the usual kind of coastal protection consisted in a summer dike. The first known decree regarding dike maintenance on the whole island was not issued until 1658, illustrating that progress in dike construction and maintenance was initially rather slow. A series of several storm surges in 1717, 1718 and 1720 largely destroyed the existing dike on Föhr. Only after the reconstructions and restorations that were executed in the aftermath of these events - speaking in today’s terms – the first real sea dike on the island was completed. The first half of the 18th century also marks the beginning of the varying development between the East and the West part of the island. In Westerlandföhr, the dike design was further improved as it can be seen for example in the enlargement of the evolution at the Western Dike (Fig. 6). Starting in 1738, a stone revetment was constructed on the outer slope of the Western Dike for further protection and dike strengthening. And again, after damages of another storm surge in Westerlandföhr in 1791, the dikes in the West and North-West were restored and heightened to better resist future storm events (Müller and Fischer 1937b).

Evolution of the coastal protection at the Western Dike (enlarged detail from Fig. 8, section rotated in clockwise direction for display purposes, north arrow below the shape of the island indicates cardinal directions). Display of the most important coastal protection related measures and events documented in Müller and Fischer (1937b) and Stadelmann (2008). Measures or events mentioned in the text are marked in the figure giving the year and a keyword

While planting of beach grass to secure sand depositions and counteract erosion was executed along Föhr’s southern coast, the protective focus in the 19th century in terms of diking was still very much on the western, northern and eastern coast. Thus, green and grey measures also co-existed on Föhr at the same time, but their areas of application were still spatially separated from each other in the beginning. New dike regulations were issued by the respective authorities in 1803 (East) and 1805 (West), putting the works on the dikes under communal supervision and thereby institutionalising coastal protection tasks around the same time as on neighbouring Amrum. The severe storm surge of February 1825 is to be mentioned here as the first of a series of storm surges that caused considerable damage to both the dikes in Westerlandföhr as well as Osterlandföhr. At the Western Dike, the storm surge produced several ground failures and a breach between Utersum and Dunsum, which was closed within the same year (see Fig. 6). In addition to the dike, two groynes made of stone and kelp were installed at the northern and southern end of the Western dike in 1863, which were further heightened and extended in 1865 and supplemented by constructions of additional brushwood groynes in 1866. Here, the dike was combined with other green or hybrid measures to advance its protective function and to safeguard the dike structure itself, by influencing the natural coastal processes around it (Müller and Fischer 1937b).

Figure 7 shows an enlarged view of the evolution of coastal protection at Näshörn, around the easternmost tip of Föhr, and poses an example for the developments in Osterlandföhr. Here, the storm surge in 1825 caused seven breaches and other severe damages along the whole dike from Wyk over Näshörn until the end of the North-Eastern Dike as indicated in Fig. 8. As emergency measures, the locations posing the biggest threats were dammed up with piles and layers of earth and straw in the weeks after the event. By the mid-19th century foreshore areas were already recognised as additional protection for the adjacent dike and the inhabited and cultivated marsh behind it. Because large parts of the previously existing foreland around the Näshörn tip were lost at the end of the previous century, officials tried to secure the remainder by the construction of angled brushwood groynes in 1838 and the following years. Despite these efforts, the storms of the winter between 1847 and 1848 caused the foreshore and the mudflats off Näshörn to disappear almost completely. The little remaining foreshore areas at Näshörn and the still existing ones off Kuham to the south were maintained and improved in the following years from 1853 to 1861. Among other things, these improving adaptations were made through the construction of drainage ditches and in the case of Kuham the installation of new brushwood groynes (Müller and Fischer 1937b). This example highlights the versatility of the concept of diking and the dynamic adaptations and possible combinations with other measures that have always been applied in response to natural processes and changes in coastal environments. Coastal protection properties of the foreland were then already well known, appreciated and used. Without the foreland, dikes had to be strengthened - with the foreland, dikes were safe and well-functioning.

Evolution of the coastal protection at Näshörn (enlarged detail from Fig. 8, north arrow below the shape of the island indicates cardinal directions). Display of the most important coastal protection related measures and events documented in Müller and Fischer (1937b) and Stadelmann (2008). Measures or events mentioned in the text are marked in the figure giving the year and a keyword

Evolution of the coastal protection on the island of Föhr. Display of the most important coastal protection related measures and events documented in Müller and Fischer (1937b) and Stadelmann (2008). Starting with the ring in the middle, each of the light grey rings represents a century; from inside to outside, the 15th till 17th, 18th, 19th, 20th (first half) and 20th (second half) century. Measures and events are divided into five categories (see legend) and shown as coloured ring segments in the figure according to their respective century and location on Föhr. The thickness of the ring segments indicates the combined number of entries of the same category at this location (see legend). The sequence of the ring segments from the inside to the outside represents the chronological sequence in this century for each location in a simplified way

In the first half of the 20th century, dikes and adjacent structures were strengthened further and suitable maintenance was promoted by the enactment of new dike regulations in 1900 (Westerlandföhr) and 1923 (Osterlandföhr). Besides, the construction of the sea wall at the city of Wyk began and opened a new chapter for the protection along the southern coast of the island (see Fig. 8). The first sea wall at Wyk was constructed in 1904 as a 280 m long concrete wall at the beach. Similar to the developments in dike construction in the previous century, progress at the sea wall can be characterised as reactive. Several storm surge damages in the years of 1909, 1917, 1923 and 1928 at different locations of the sea wall instigated a constant advancement and improvement of the construction (Müller and Fischer 1937b).

In the second half of the 20th century, after the first joint plan to secure the entire Föhr sea dyke was issued in 1951, work began in various steps from 1953 onwards. The severe storm surge of 1962, however, ensured that a new extension programme was launched before the reinforcements were completed. Authorities decided to reinforce all dikes again and to upgrade them with a sand core, a flat outer slope, an inner berm and dike defence paths. The work for this began within the same year and continued for the next decades (Stadelmann 2008). The loose association of communities interested in the protection of the island’s south coast established in 1952, which ultimately led to the foundation of the South Coast Association (‘Zweckverband Südküste Föhr’) in 1969, which represents the kick-off for the intensive efforts to preserve Föhr’s southern coastline (Stadelmann 2008). A change in the coastal protection strategy from grey to green measures can be observed on locations like the Clinic Utersum or Nieblum in the years following the first ever sand nourishment on Föhr in 1963, which was executed between Wyk harbour and Oldenhörn with a volume of 180,000 m3 of Sand. After restoring the previously extended revetment off the Clinic as a reaction to storm surge damages in 1976, a sand nourishment was executed and two rubble stone groynes were constructed in 1977 to secure the coastline. The nourishment was renewed twice in the following decades, once in 1982 and once in 1990 in response to storm surge damages dating from January of the same year. A similar development took place off Nieblum. Following the construction of a boulder groyne to secure the beach, the first sand nourishment on Nieblum beach was executed in 1975 with a volume of 290,000 m3 of sand. As with the Clinic, the nourishment at Nieblum beach was replenished in 1982 and renewed after the storm surge in 1990 (Stadelmann 2008). While authorities stuck to the system of diking in the North of the island, coastal protection on the South coast was more open to change and experiments. As described above, even after severe damages through storm surges, authorities did not deviate from Föhr’s dikes but rather made them higher and stronger. In the South of Föhr, coastal protection evolved more dynamically and proved to be open to change and going new ways, as the deployment of sand nourishments instead of revetment or dike construction indicate.

The development of coastal defence on Föhr is summarised and depicted in Fig. 8.

Comparison of the evolution

Recognition of the importance of the natural ecosystems for the preservation of the island has a history on Amrum that had its beginnings in a time when the technical possibilities for coastal protection were naturally still limited. However, it continues to this day that islanders could and still can rely on natural protection such as the wide dune belt and the Kniepsand beach. Multiple combinations of grey and green measures were implemented, experimented with and further developed - a problem-oriented and pragmatic way of dealing with coastal protection was relied on, which did not rigidly follow a straight developmental path but interacted dynamically with the changes experienced. On Föhr, due to differing environmental preconditions in comparison to Amrum, diking was more important throughout the development of Föhr’s coastal protection. Nevertheless, other measures were applied as well and advanced coastal protection on the island. In a reactive and problem-oriented manner, dike construction evolved as a major part of Föhr’s protection strategy - but not as the exclusive one. Combinations of grey and green measures were tested and implemented and, driven by storm events and changing boundary conditions, innovations in diking and more nature-based concepts dynamically advanced the island’s coastal protection over the course of the past centuries.

Status quo

As a consequence of the storm surge in 1962, the first special plan for the general planning of coastal protection throughout Schleswig-Holstein, which was published in 1963 and updated twice in the following decades in 1977 and 1986, stipulated the reinforcement of the existing dikes and laid the foundation for a uniform strategy and coastal protection concept for the entire federal state. In 2001 a new general plan for coastal protection was issued by the federal state ministry, based on the principles of integrated coastal zone management (MELUR 2012, MELUND 2022). In addition to coastal protection that had been built and evolved by 2000, the new construction programme, that went hand in hand with this plan, marks the starting point for the realisation of the coastal protection systems that represent the current status quo. The core of the new plan was a dike reinforcement programme including a so-called ‘climate buffer’ of 0.5 m for the expected anthropogenic sea level rise. In the following, the status quo of coastal protection on Amrum and Föhr is summarised. According to the definitions for grey, green and hybrid coastal protection measures given above (see “Evolution of coastal protection on Amrum and Föhr”), the currently prevailing measures on Amrum and Föhr are displayed.

Amrum

Around the northernmost tip at Amrum Odde dunes are the prevailing habitat, and these dunes are secured by sand trapping bush fences (see Fig. 9, left). Moving clockwise to the eastern side, brushwood groynes are installed in front of the dunes to accrete sediment. These fields of brushwood groynes continue further along the coast where an asphalt overflow dike is constructed in front of the Norddorfer Marsh. This combination is then followed by a combination of a stone revetment with adjacent fields of brushwood groynes. As can be seen in Fig. 10, coastal protection is lacking in the following section on the east coast. Subsequently, only some of Nebel’s houses are protected by an embankment. The coastal section at Steenodder Cliff just before Wittdün is secured by regular sand nourishments.

Status Quo of the coastal protection on the island of Amrum. Display of the currently prevailing coastal protection measures as inspected on site and as documented in the special coastal protection plan for Amrum (LKN.SH 2017). Measures are divided into three categories (see legend) and shown as coloured ring segments in the figure according to their respective location on Amrum

Similar to the Norddorfer Marsch, the Wittdüner Marsch is protected by an overflow dike, followed by sea walls with additional revetments, which are protecting the actual city of Wittdün. In the South of the city the longitudinal coastal protection works merge into the adjacent dunes. Several groynes are installed there to counteract erosion and secure the coastline.

Behind Wittdün in the south-east, the extensive dune area of Amrum begins to extend northwards along the west coast of the island (see Fig. 9, right). In addition, from the south of the island to the north-west just before Risum, the wide Kniepsand extends in front of the dunes, nourishing and protecting them. The prevailing currents cause it to shift northwards along the island. Up to the easternmost tip it is therefore in decline, while it continues to grow north of this point. The formerly constructed asphalt dikes around Risum still exist in their original form but are nowadays completely covered by dunes, maintaining the dune chain intact along the entire west coast in its current state.

The status quo of Amrum’s coastal protection is depicted in Fig. 10 in a categorised manner, displaying the variety of applied measures and concepts in Amrum’s coastal protection.

Föhr

The entire Marsh area of Föhr is protected by the dike, which stretches from Utersum in the West along the north coast of the island to Wyk harbour in the south-east. The dike profile varies along the whole construction. Designs differ mainly in the gradient of the outer slope, the design at the bottom of the outer slope and additional features such as roughness strips.

Starting in the West, the coastline between Utersum and Dunsum is additionally secured by several groynes constructed in the North Sea in front of the dike. Moving clockwise around the island, a large foreland area stretches out in front of the sea dike from the north-western corner of the island to the north-east, with its maximum extension in the North. Fields of brushwood groynes in the north-east are constructed to accrete more sediment and help build up more foreland areas in front of the dike (see Fig. 11, left). These measures are continued until the easternmost tip of Föhr at Näshörn.

After the harbour dike, the city of Wyk is protected by sea walls in combination with revetments for erosion protection. Furthermore, several groynes are constructed at the eastern beach and the southern beach is being nourished regularly. A rubble stone revetment is connecting the city area, which is protected by sea walls, to the area around Greveling, where an asphalt overflow dike is constructed behind the beach.

Continuing on from the area around Wyk and Greveling, coastal protection on the south coast of Föhr is in part very small-scale, localised, and lacks a holistic concept. While the section adjoining Greveling lacks coastal protection, the coast of Nieblum is protected by the old dike and regular nourishments. These have also contributed to the dyke being covered by sand over the years, which is why nowadays it more or less resembles a dune. The rest of the southern coast is either protected by further sand nourishments, as in the area in front of Goting and at the south-western tip of Föhr off the Clinic Utersum, or by a beach ridge. Around the mouth of the Godel, the coast is secured by additional riprap and groynes are constructed at the beach in front of the Clinic Utersum (see Fig. 11, right). Additionally, three single embankments are constructed further inland to protect individual houses and farms in Hedehusum, Witsum and Goting.

The status quo of Föhr’s coastal protection is depicted in Fig. 12 in a categorised manner. Although on Föhr diking was very present in the past and still is of major importance today, it becomes clear that this is not the only form of coastal protection applied on the island today.

Status Quo of the coastal protection on the island of Föhr. Display of the currently prevailing coastal protection measures as inspected on site and as documented in the special coastal protection plan for Föhr (LKN.SH 2019). Measures are divided into three categories (see legend) and shown as coloured ring segments in the figure according to their respective location on Föhr

Stakeholders’ perspectives on historical, present and future dynamics in coastal protection

The preceding depiction of the historical development of coastal protection in the study area has shown - contrary to the prevailing public discourses - that coastal protection could be characterised as problem-oriented, pragmatic, dynamic and, in view of the measures taken, hybrid. The socio-historical ways of dealing with coastal protection presented in “Evolution of coastal protection on Amrum and Föhr” hence show that coastal protection has in fact always been characterized by an inherent dynamic and ways of tinkering. To investigate if and how stakeholders perceive this divergence between commonly shared synchronic narratives and historical developments in the present, 14 interviews with stakeholders from local as well as regional authorities and NGOs were conducted (further 21 interviews were conducted with actors in science and islanders). Analytical emphasis was put on the linguistic structures used as this can assist in revealing how certain issues are perceived, framed and integrated into existing meaning systems to develop social representations about how coastal protection was, is and should be carried out. This will show that coastal protection is not exclusively an engineering issue, but genuinely a social process – an aspect which has to date often been overlooked. Institutions play a major practical and normative role in and for negotiating and implementing coastal protection. In the following, these interviews will be analysed in more detail, as various framings and assessments of coastal protection can already be identified here. The empirical categories revealed and used for the analysis are Coastal Protection, Nature-based Solutions, Interface Coastal Protection - Nature Conservation, and Future of Coastal Protection. These have been selected from a larger group of empirical categories emerging from the interviews as they directly relate to the research questions mentioned at the start of the paper – an overview over the whole category set including all sub-categories can be found in the Appendix of this paper. In the following sections, a detailed analysis of paradigmatic examples taken from these four categories will be provided. The guiding questions permeating the sections are what was, what currently is and what will be happening in coastal protection?

Coastal protection

Coastal Protection – though not astonishingly – permeated the reflections of all interviews. In most of the cases, the process of reflection starts with depicting a sometimes vivid image of the past, e.g.

‘You see, they still fortified the dike by hand. (...) they still tried to protect the dike with long rye straw, to hold it (...).’

‘Yeah, well, I mean, dikes have been built here on the North Sea coast for thousands of years. I would say that this has proven itself.’

Both references craft a past and generic image of diking as hard manual work which is complemented in the first quote by the aim to secure the dike, and consequently to protect the livelihoods behind it against the forces of the North Sea. This representation uses a socially shared imagery that appears now and again when the issue of coastal protection and diking in North Frisia is raised. It is often complemented by a thematic anchoring that reveals processes of objectification based on an imagery revolving around the fight against the sea, the forces of the sea and the struggle humans have to go through to protect their livelihoods behind the dikes. Such a socially constructed and widely shared history about diking reveals a stark contrast to contemporary procedures of diking because these are scientifically driven and business-like engineering processes often using heavy machinery. This line of thinking is furthermore elaborated upon in the second interview except where the usefulness of the diking rational is temporally outlined. and connects its temporality to the supposedly long-lasting experiences made with diking throughout history. The conclusion ‘that this has proven itself’ frames diking as an adequate technique. However, this focus in perspective partly hinders the broadening of the view resulting in the fact that alternative concepts and measures were and currently are seldom considered.

Another important aspect, that is strongly influenced and shaped by the past, is the status and relevance of coastal protection. This more abstract and social aspect is often portrayed in individualised terms referring to personal experiences also using paradigmatic or exceptional events as in the following example:

‘(...) and from earlier times it was like that, I mean, in 1962 I can still remember it from hearsay, I was four years old (...) and the dike was threatening to break. (...) and that’s why coastal protection is essential for me to live on the islands, on the holms, on the mainland.’

Here, the temporal reference ‘from earlier times’ in combination with the individualised memory of the 1962 storm surge – a thematic anchor – provide a frame of reference, that is used to strengthen the relevance of coastal protection.

The aforementioned aspect is insofar important, as if disasters are situated too far in the past, the memory of them and the fears associated with them hold the danger to fade further and further resulting in oblivion. Hence, the topic of coastal protection is slipping out of the individual and common focus in the context of an increasing security and prosperity achieved by a well-executed coastal defence. A process, that is conceived by some interview partners as being amplified by the increasing institutionalisation of coastal protection and growing social prosperity in recent decades:

‘So, of course, this is due to a social development of prosperity, where you can claim all kinds of things with a big belly and a big salary. You don’t take any risks. (...) We have taken more and more responsibility away from the local people as a state. (...) well, so one relies more (...)’

Here, a rather general picture about society and its relation to coastal protection is developed. The representation of social prosperity, objectified via the negative images of ‘a big belly and a big salary’, and its consequences for coastal protection is reflected upon. Taking away responsibility from local people is assessed as a sign of the times in view of the overall caring state and its authorities in charge. Hence, the ‘exemplary care and provision’ of governmental coastal protection poses a reflexive threat to its status for some interview partners. On the one hand, due to its well-functioning, no severe flooding has occurred on the German coast since 1962. Hence, coastal inhabitants feel safe and the former fear of the sea is more and more pushed aside, ignored or even forgotten. This is of course a positive development, as long as the general interest in coastal protection and the respect for the forces of nature are not lost at the same time. On the other hand, the institutionalisation and professionalisation of coastal protection entail that coastal dwellers are less and less involved in these processes which lead to alienation, a lack of interest and practically no engagement with the issue. In the past, as we have seen in “Evolution of coastal protection on Amrum and Föhr”, it was the task of those living behind the dikes to take direct responsibility for the facilities protecting them. Nowadays, the general picture is somehow reversed since institutions like the ‘Landesbetrieb für Küstenschutz, Nationalpark und Meeresschutz Schleswig-Holstein’ (LKN; Schleswig-Holstein State Agency for Coastal Protection, National Park and Marine Conservation) are in charge of maintaining the dike line and by doing a good job, accidentally fuel a lack of interest for issues revolving around coastal protection. However, coastal protection is seen – as expressed in the following quote – as the basis for enabling people to live on the islands and the coast.

‘To me, coastal protection is the foundation for enabling people to live here in this region.’

This widely shared representation implicitly includes aspects of coastal protection such as safety, the protection of human life, shoreline protection, or in slightly more engineering terms, the two areas of flood protection and shoreline stabilisation. From the perspective of nature conservation however, the assessment can be much more negative as coastal protection also comprises the obstruction of nature or the destruction of natural coastal ecosystems through artificial structures and barriers.

‘From my point of view, it is first of all something where one has the feeling that they are constantly stepping on nature’s toes, making it constantly smaller and destroying it.’

This representation illustrates the impact measures of coastal protection have on the natural environment. By doing so, it challenges the rational of coastal protection and refers to its continuing obstruction of the natural development - or of nature per se - as well as the destruction of nature. In line with these varying and partly opposing rationales, the process of diversification in coastal protection will certainly continue in the future, in view of new challenges such as climate change. The decisive criterion for future development seems to be sea level rise, as it is expressed in the two following quotes:

‘If, for example, the issue is now, when we strengthen dikes, ”to what level?”, then of course we take that into account there, that the sea level rises (...)’

‘So basically, in the long term, sea level is ... determines how the coast develops, not the storm surge.’

Across all responsible authorities and NGOs involved, sea level rise is perceived as the main criterion when it comes to the future design of coastal protection. This representation includes efforts that will be needed that are regarded as economically and socially sound and will shape the future of the coast in general. How these unavoidable challenges, that come with sea level rise, are to be met, is assessed differently among the interview partners. Some of those responsible are aware of the enormous future change and various consequences on the technical, institutional and social level, while others do not see it as a reason or even a necessity to rethink or change the established ways of executing coastal protection.

‘Nevertheless, for us that does not mean that we would, let’s say, make changes to the way we do coastal protection.’

Based on a representation that implicitly uses the path dependence of historical experience, the current practice of protecting the coast and its underlying path dependency is legitimated and sustained for the time being. As long as it does not prove to be unsuitable, there is no reason for change, regardless of the demands upon coastal protection as described above. Others, however, raise the issue of a need for new perspectives, methods and strategies to meet future challenges on the coast:

‘(...) there are areas that also have to be processed with completely different, well, perspectives and methods, where you have to have completely different strategies.’

This perspective obviously contrasts with the aforementioned aspects raised. It is grounded in a representation referring to the need of change in perspectives, methods and finally strategies. To objectify this more or less abstract thinking, spatial images such as ‘area’, ‘way’ or ‘path’ characterise this thinking outside the box which is still in the process of conceptual structuration. Hence, in addition to the path-dependency, the engineering-based protection and preservation of the coast, ecological and social concerns seem to gain relevance and should also be taken into account. One concept that enables the combination of these three areas - Water, Nature, People (e.g. Watkin et al. 2019) - are NbS in coastal protection (c.f. Jordan and Fröhle 2011).

Nature-based solutions

In the analysis of stakeholders’ views and ideas on NbS, the forces of nature in the coastal zone have always come up in the past as well as in the present. Especially in the past, not all natural processes could be fully understood or were significantly underestimated.

‘I think that many, well, processes or many things have already shown this, where one has tried to basically lock the coast, but in the end, it has not necessarily worked as intended, because the natural processes are simply too strong and it is sometimes really better (...)’

Thus, working in and with nature in the coastal zone has always been particularly challenging, as natural forces were and are sometimes unpredictable. This representation is informed by the rationale of locking the coast on the one hand while one the other hand processes of tinkering in coastal protection in terms of the trial-and-error principle existed as well. Interestingly though, the aspect and image of locking the coast in terms of dikes was strongly cultivated in the past decades while the aspect of tinkering was less stressed although it was common practice. This is astonishing as in many locations in the region of North Frisia and on the islands, it has already been shown in the past that working against nature and natural processes - for example, rigidly fixing the coastline or blocking off entire bays from the sea - is laborious and often futile. Consequently, an understanding of natural processes was needed in order to work with and not against natural forces. This basic idea, which also underlies the current understanding of NbS in coastal protection, has - as described in “Evolution of coastal protection on Amrum and Föhr” - already been pursued in the region. The genuine practice of orienting one’s work towards natural processes and systems for one’s own purpose has already proven to be efficient over the last decades or centuries.

‘(...) and here, too, I have to say that we have been practising foreshore management since the end of the century before last. So that’s nothing new either.’

Including the foreshore area with e.g. salt marshes into the coastal protection strategy - today framed as a nature-based concept or measure under the umbrella term of NbS - has thus been proven to be useful for a rather long time in a number of cases. The temporal indication ‘since the end of the century before last’ emphasises the extended period of time which might have contributed to a habitualisation and the framing of this issue by the interview partners as ‘nothing new’. When considering NbS in coastal protection, it is sometimes disregarded or forgotten among locals and scientists that in many cases these are not completely new measures, ideas and concepts, but often already existing practices which are just bundled under the comparatively new umbrella term of NbS.

In the recent decades, approaches to coastal protection like NbS that differ from the concept of diking were often being met with scepticism and doubt on the local level.

‘(...), but the reaction on the local level was not in a way that any of the coastal protection officials felt encouraged to pursue this further (...)’

This scepticism on the side of the local population often led to a lack of courage on the side of the authorities in charge to plan and implement innovative approaches, although this has already been done unnoticed for a long time. This representation of social scepticism towards other ways of doing coastal protection in terms of already existing NbS approaches resulted in a lack of encouragement, support and trust, as well as sometimes fierce pushbacks, which finally resulted in the reaction of authorities to not yet officially pursue new approaches, such as NbS in coastal protection.

However, the forces of nature and their potentials are nowadays much more present among the stakeholders interviewed than they were just a few decades ago.

‘So nature helps itself, so to speak. Or nature helps man.’

The representation of nature’s self-sustaining processes and their value for humans is increasingly being recognised and epitomises a perspective gathering more and more attention among those involved in coastal protection. Hence, the central point of NbS seems to have just arrived in the field of coastal protection. However, the potential of nature to support itself and humans naturally has certain limits, as exemplified in the following quote:

‘In other areas, we know that nature cannot regulate this at all, because there is simply a lack of material. If there is no material, then there is nothing.’

Human intervention in natural systems can impede natural processes and functions. If, for example, there is a lack of sediment or the supply of plants is too low – i.e. there is a lack of material with which nature can work – then even nature is powerless and the so-called forces of nature reach their limits. Within these limits, where nature contributes to coastal protection or coastal protection actively uses natural processes and systems, acceptance among stakeholders for such nature-based measures has already increased to a certain extent.

‘On Sylt the situation is very tense, because the island is much more strongly attacked by the North Sea (...). On Amrum, the dune belt is much wider, so that you can say, okay, it looks quite nice and just let it happen. I find that very appealing about the island of Amrum.’

Here, the representation of two islands is depicted that is widely shared among all stakeholders involved in the study. While Sylt is objectified as ‘strongly attacked by the North Sea’, Amrum appears not to be as threatened as Sylt. This opposition is, moreover, characterised by the adjective ‘tense’ that describes the situation and the atmosphere felt in view of Sylt as compared to Amrum. If the situation is difficult, the acceptance for deviating from established concepts of coastal protection is still limited among locals as well as officials. If, on the other side, the risk of damage and danger to life from storm surges and flooding is low, as is evaluated by the interviewee to be the case on Amrum with its protective dune belt, the acceptance of coastal dwellers and their willingness to think about and test new approaches in coastal protection increase significantly. This could open up opportunities for pilot projects and experimental research.

Despite this partial serenity, as long as projects do not come at the expense of safety, many obstacles remain. In the future, more work is needed to conceptually integrate NbS into the practice of coastal protection, especially into the perception of coastal protection of all stakeholders involved. This aspect is raised in the following quote:

‘There will be a lot of work to do until the local people and those responsible realise that this is a favourable solution.’

This representation is shared among many of those involved in coastal protection using the phrase ‘a lot of work’ in the temporal as well as in the sense of effort to be performed. The underlying objectification of a way in which the ‘favourable solution’ represents a goal and the current state of the art a starting point, is characteristic for the comparable quotes gathered. Although NbS are said to be financially and conceptually effective and efficient in terms of time, it still has a long way to go before such measures are truly accepted at the local and institutional level.

There is, however, another representation that frames the issue differently. According to these interview partners, standstill cannot be an option in coastal protection when future challenges on the coast, not least due to climate change, need to be handled. A new line of thinking is needed as depicted in the following interview excerpt:

‘We need to think of the multiple benefits that can then accrue to society as a whole from new ways of doing things. But whether that really works is something that needs to be experimented with. So that’s what I really wish for, that we become more open.’

This representation again uses the image of a ‘way’ to objectify the need for change. The ‘new ways of doing things’ is complemented by the need to experiment and tinker with these possible measures to instigate progress resulting in a though unspecified process of social accretion. However, experimental approaches and new concepts are always abstract and often accompanied by a certain risk. From the side of the authorities, a certain willingness to take such risks and an openness towards nature-based pilots in coastal protection is being signalled.

‘We would like to develop such pilot projects and then also realise them, so that one can really experience this first hand. According to the principle that you can write down a lot of good ideas, but when you actually realise them, you only become aware of the difficulties that may arise.’

Here, the question remains, what is then still holding back the responsible authorities? Possibly, the fact that it is still questionable among the representatives of the authorities whether such a new way of doing coastal protection can prove itself. The NbS approach is initially perceived from a rather negative perspective. There is no talk about opportunities, but rather of difficulties and obstacles that only become apparent in practical trials and not in theory on paper. As already mentioned, the opposition between the abstract and practical or between engineering practice and science is evident here.

New strategies and concepts, as we have seen in this section, need time to develop, they cannot be launched overnight, but should be started in the here and now and consider the socio-historical experiences made. In brief, approaches such as NbS require sensitive planning and participation as nature should be promoted and stakeholders should be part of this process as well. This reconciliation between ways of connecting nature and the social would be the only way to gather support for such sustainable measures in the long run.

Interface coastal protection - nature conservation

Taking a closer look at the interface between coastal protection and nature conservation in the investigation area, it becomes apparent that many conflicts between the people working in the two areas are based on the introduction of the national park. The conflict at that time about the implementation of the national park is an important anchor of memory and in many cases is still today divided into two different representations that harden positions between coastal protection and nature conservation.

‘Well, there are so many issues that weigh on this and... in the past it was said that this has no influence on coastal protection at all. Coastal protection has priority. But because of all the generational changes that have taken place, that was in 1985, I think... well, and then ... they were all against it here in the region. Everyone was against the National Park, ‘we don’t want it any more’, like that. And then it was decided in Kiel, so it was determined by others here in the region.’

As articulated here, the promised prevalence of coastal protection over the protection of nature has disappeared. This aspect is, furthermore, complemented by various thematic anchors that depict the events that have taken place during the implementation of the national park. Such experiences also play a role in the context of coastal protection and nature conservation in which members of the opposing groups had to gather under the institutional roof of the LKN where coastal protection partly lost its priority to nature conservation:

‘In the past, it was intended differently when it became the national park, that coastal protection should have priority. But now they say, no, no, let nature be nature, that has priority, because we are a national park.’