Abstract

Previous research has indicated that the impact of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) on performance is ambiguous. This relationship can be affected by numerous factors – both internal and external. This study aims to examine the moderating impact of inter-organizational cooperation, competitive behaviors, digitalization, diversification, and flexibility on the relationship between EO and performance; it also assesses the impact of market conditions on the relationships that were examined above. The sample was comprised of 150 small printing companies, and the moderating roles were analyzed with PLS-SEM. The results confirmed the strong positive impact of EO on firm performance under both non-crisis and crisis conditions. The results indicated that, under crisis conditions, the impact of EO on market performance is positively moderated by inter-organizational cooperation, digitalization, and diversification. However, these factors do not moderate the examined relationship under non-crisis conditions – they only become moderators during a crisis. When supported with the Welch-Satterthwait statistical test, these observations indicated the moderating role of market conditions on the other factors that were examined in this study. With its findings, this study contributes to the literature on entrepreneurship and crisis management. The originality of the study is two-fold: first, this study examines the moderating impact of several factors that have not been previously tested on the EO–performance relationship; and second, it compares the examined models (and the entrepreneurial behaviors that are reflected in these models) and tests the moderating roles of the examined factors under two different market conditions (non-crisis, and crisis). In this way, the study tests the moderating role of market conditions as it relates to the examined moderators.

Highlights

• Market conditions moderate the impact of the moderators of the relationship between EO and performance.

• As moderators in the relationship between EO and performance, the roles of inter-organizational cooperation, digitalization, and diversification vary along with the changes in market conditions (in particular, they become moderators during a crisis, whereas they do not under non-crisis conditions).

• Under crisis conditions, the impact of EO on market performance is positively moderated by inter-organizational cooperation, digitalization, and diversification.

• EO positively and strongly impacts firm performance under both non-crisis and crisis conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The impact of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) on performance is one of the most-examined relationships in organizational studies. Despite the numerous studies, there is still confusion about this impact (Andersen 2009); some studies have shown a strong association (Rauch et al. 2009), while the others have shown a low or insignificant correlation (Renko et al. 2009). Some research has suggested the existence of mixed or non-linear relationships between EO and organizational performance (e.g.Tang et al. 2008; Wales et al. 2013b; Rezaei and Ortt 2018; Morić Milovanović 2022). As EO is a multidimensional construct (including risk-taking, innovativeness, and proactiveness), the particular dimensions of EO can interact with each other (Putniņš and Sauka 2020; Wach et al. 2023).

The relationship between EO and performance can depend on the context (e.g., Andersen 2009; Lomberg et al. 2017) and can be affected by other factors (see, e.g., Tang et al. 2008). In this vein, Lumpkin and Dess (1996) suggested the consideration of another factor that can moderate the EO–performance relationship. Indeed, numerous studies have confirmed such associations; for example, the relationship can be affected (moderated or mediated) by a firm’s strategy (Moreno and Casillas 2008), decision-making style (Covin et al. 2006), high-performance work system and partnership philosophy (Messersmith and Wales 2013), performance-based culture (Semrau et al. 2016), education and networks (Ferreira et al. 2021), network range and closure (Kreiser 2011), organizational learning (Real et al. 2014), and knowledge integration (Jiang et al. 2021).

Among those factors that affect EO and its relationships with performance is also the external environment (Rosenbusch et al. 2013); however, its impact is also unclear in this case. Previous research has suggested that a hostile environment requires firms to behave entrepreneurially (e.g., Covin and Slevin 1989; Martins and Rialp 2013) and develop dimensions of EO (i.e., risk-taking, proactiveness, competitive aggressiveness, and autonomy) (Lumpkin and Dess 2001; Dele-Ijagbulu et al. 2020); this also refers to external crises (Kraus et al. 2012; Kusa et al. 2022a; Suder 2023). A hostile environment can also force companies to reduce their entrepreneurial behaviors (Kreiser et al. 2020); however, this relationship can vary depending on a firm’s size. Rosenbusch et al. (2013) posited that small firms tended to avoid risk and did not behave proactively in hostile environments due to their limited resources. Consequently, a hostile environment does not affect EO in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Meanwhile, the crisis that was caused by the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the sensitivity of small firms to unfavorable external conditions, including changes in demand and income (Pedauga et al. 2022). For example, 72% of small firms in Poland were affected by declines in sales (Adamowicz 2021) and 63% by declines in new orders from customers as well as liquidity problems (Dębkowska et al. 2022). This suggests that these companies needed to take entrepreneurial approaches to those challenges that were sourced in their environments. Due to their characteristics, however, they need different solutions than large companies do. Small businesses differ significantly from large companies – not only in terms of their limited financial and human resources (Theng and Boon 1996), but also in their lower likelihoods to seek financing from external sources (Berggren et al. 2000) as well as their tendencies to be less professionally managed (Pauli 2020), to have less relational capital (Cegarra-Navarro and Dewhurst 2006), and to have considerable difficulties finding alternatives to their existing portfolios of resources (Sarsah et al. 2020). Not surprisingly, Calabrò et al. (2021) considered the basics of business continuity for SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite that fact that SMEs are more affected by economic crises than large firms are (Soininen et al. 2012; Bartik et al. 2020), little is still known about the behaviors of these companies when facing changes in market conditions. Knowledge on this topic effectively eludes the methods and techniques that are used by researchers. The hostility, complexity, ambiguity, and volatility of the environments of SMEs lead to the emergence of new unforeseen trends, negative consequences for the organizations, and increases in their risks of doing business. They find their important places in models and approaches and are taken into account in empirical studies (e.g., Sullivan-Taylor and Branicki 2011; Nyaupane et al. 2020). At the same time, the role of other factors that influence the relationship between EO and performance under challenging environmental conditions has not been explored. Unforeseen risks such as disasters, natural events, and crises that are caused by various factors have caused a sharp increase in the number of publications in recent years (Bhaskara and Filimonau 2021; Ozanne et al. 2022). Adverse phenomena obviously focus the attention of the public and researchers, leading to the search for answers to constantly emerging questions.

Following the position that, despite the numerous studies, the relationship between EO and organizational performance remains unclear and requires further investigation to explain the mixed findings (Real et al. 2014; Wales 2016), this study builds on two lines of research: those that explore the roles of those factors that affect the relationship between EO and performance, and those that explain the role of market conditions. Also, this study focuses on the research gap regarding the associations between market conditions and the other factors that affect the relationship between EO and performance.

Thus, this study aims to explain the role of market conditions. In particular, the purpose is to examine the impact of market conditions on selected moderators of the EO–performance relationship (how changes in market conditions affect the impact of the moderators). Furthermore, the study aims to examine the impact of EO on firm performance and the impact of selected factors (namely, the moderating roles of inter-organizational cooperation, competition, digitalization, diversification, and flexibility) on the relationship between EO and firm performance under different market conditions.

As contextual factors can support or inhibit entrepreneurial behavior (Slevin and Terjesen 2011), it is necessary to consider them in order to understand the EO–performance relationship. Therefore, this relationship will be examined under both non-crisis and crisis conditions in this study; thus, data that was related to two different market conditions (occurring during two different periods) was collected and analyzed.

To test the moderating effects, this study employed the SEM methodology. Additionally, the Welch-Satterthwait test was used to verify the significance of the observed differences regarding the moderating roles under different market conditions (and, consequently, to test the moderating role of market conditions). The sample was comprised of 150 small printing companies. As stated before, SMEs tend to be less prepared for unexpected unfavorable situations and, thus, adversity (Ingram 2023); this was revealed by the COVID-19 pandemic. In parallel, the printing industry was seriously affected by the pandemic crisis; thus, small printing companies met the conditions of being a subject of examinations of the proposed relationships.

This study intends to contribute to the literature on entrepreneurship and strategic management by testing the roles of several factors that have the potential to increase firm performance as well as by investigating the role of external conditions. In particular, the study intends to contribute to the discussion of the role of inter-organizational cooperation versus competition in strengthening a firm’s outcomes. The originality of the study lies in examining models that are comprised of entrepreneurial behaviors (including those behaviors that play moderating roles) under two different market conditions (non-crisis and crisis). By setting the study in a crisis context, the study also contributes to research on crisis management. The SME context of the tested relationships offers the opportunity to contribute to the literature on small businesses. The intended findings should be important nowadays, as the variability of the external environment is increasing (including the severe changes that are caused by crises). This requires more entrepreneurial actions, as such an environment can be especially challenging for small firms due to their limitations (discussed above). Finally, the study intends to contribute to the research methodology by testing the procedure for examining double-level moderation (that is, a model wherein the roles of moderators are affected by another factor).

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Entrepreneurial orientation and performance

Entrepreneurship is commonly understood as the pursuit of opportunities. In this view, research on entrepreneurship has been conducted in different types of organizations, ranging from large enterprises (Rauch et al. 2009; Rosenbusch et al. 2013) through SMEs (Sidek and Mohd Rosli 2021; Isichei et al. 2020; Duda et al. 2023), manufacturing (Bouncken et al. 2016) and services (Kraus 2013), and non-profit organizations (Morris et al. 2011; Lumpkin et al. 2013).

At the organizational level, entrepreneurship is reflected in the concept of EO; it is based on Miller’s description (1983:771) of an entrepreneurial firm, which was “one that engages in product-market innovation, undertakes somewhat risky ventures, and is first to come up with proactive innovations.” According to Covin and Slevin (1989), EO is comprised of three dimensions: risk-taking, innovativeness, and proactiveness. Other conceptualizations also include autonomy and competitive aggressiveness (Lumpkin and Dess 1996) or link EO with strategic flexibility (Ali et al. 2021; Kusa et al. 2022b) or inter-organizational cooperation (Kusa et al. 2019).

Numerous studies have indicated that the entrepreneurial activities of organizations are related to organizational performance (e.g., Miles et al. 1978; Peters and Waterman 1982; Drucker 1985; Covin and Slevin 1991; Zahra 1993; Kraus 2013; Wales et al. 2013b; Saeed et al. 2014; Teece 2017; Gupta et al. 2020; Anwar et al. 2022) as well as development (Hughes and Morgan 2007; Chaston and Sadler-Smith 2012). These relationships have been investigated in national contexts (Covin and Lumpkin 2011; Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Miller 1983; Polonsky et al. 2005) as well as in international contexts (Basco et al. 2020). EO also interacts also with performance at team level (Wójcik-Karpacz et al. 2022). Most scholars agree that entrepreneurially oriented companies tend to perform better than conservatively oriented companies (Rauch et al. 2009; Wiklund and Shepherd 2011; Rosenbusch et al. 2013). A significant impact of EO on performance is also visible among micro, small, and medium firms (e.g., Kraus et al. 2012; Kiyabo and Isaga 2020; Abu-Rumman et al. 2021; Kusa et al. 2021), including startups (Sen et al. 2022).

Particular EO dimensions can have different impact on performance (e.g., Kallmuenzer et al. 2018; Isichei et al. 2020). Furthermore, these dimensions can interact when affecting performance (Putniņš and Sauka 2020; Wach et al. 2023). Understanding whether higher EO results in increased performance is a critical step in building a predictive theory (Goldfarb and King 2016) and in providing useful information to managers (Ghoshal 2005). The above statements lead to a hypothesis that EO positively impacts firm performance (as follows):

-

H1: EO positively impacts firm performance

As stated in the introduction, this study aims to identify those factors that affect the EO–performance relationship under different market conditions (i.e., non-crisis, and crisis). Despite the fact that testing both mediation and moderation relationships can be justified (see, e.g., Kraus et al. 2023), this study focuses only on the moderation effect; this is because we have examined behaviors in two periods, where the second period (i.e., the first quarter of the crisis) was relatively short. We argue that the mediation effect is not observable in such a short period (as in the case of mediation, the impact of an independent variable on a mediator must occur before we can observe the impact of the mediator on a dependent variable; thus, much more time is required to observe the mediation effect than in the case of one cause-and-effect relationship). Consequently, this study has examined only moderation effects.

Based on the results of interviews with entrepreneurs (which were conducted during the first phase of the study; the research procedure is described in Section 3), we selected five moderators for the examination; namely, inter-organizational cooperation, competitive behaviors, digitalization, diversification, and flexibility. These were indicated by the interviewed entrepreneurs as being relevant in the crisis context. Moreover, these can coexist; for example, developing cooperation with external entities could allow a company to increase its flexibility (Sen et al. 2022).

2.2 Inter-organizational cooperation

Cooperation is the ability to create bonds and work with others as well as work in a group toward the attainments of shared goals. This is also the skills of task-execution and problem-solving on a team as well as one of the competencies that conditions the capability of building good relationships with other people and/or organizations. The notion may apply to both individuals (team members) and organizations (including enterprises) (Duda et al. 2022). The type of cooperation depends on the defined objectives of a company and its adopted strategy (Duda 2023). Inter-organizational networks contribute to the foundation of effective entrepreneurial ecosystems (Scott et al. 2022).

Inter-organizational cooperation can have a positive impact on company performance (Kusa et al. 2022a). Collaboration with external partners enables a company to gain resources (including knowledge) (Welbourne and Pardo-del-Val 2009; Nason and Wiklund 2018), reduce its operational costs (Banchuen et al. 2017), and enhance its innovativeness (Alexiev et al. 2016); this also fortifies its competitive advantages (Dyer and Singh 1998) and continuous improvement (Fawcett et al. 2008). In the international context, cooperation with foreign companies helps SMEs gain new ideas and enter the market with new products (Liefner et al. 2006), improve their internal processes, and increase their performance (including environmental-related performance) (Sitawati and Winata 2018; Pavlova 2019).

Inter-organizational collaboration is not usually perceived as the demonstration of an entrepreneurial posture. For instance, individuals are those who are principally described as entrepreneurs (Shams et al. 2020), and competitive aggressiveness is proposed as a dimension of entrepreneurial orientation (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). However, an entrepreneurial context must be considered in some premises. For example, the collaborative approach can lead to an increase in firm performance when it is accompanied by dimensions of EO (innovativeness or proactiveness) (Kusa et al. 2022c). Additionally, inter-firm cooperation is positively related to innovation performance in SMEs (Zeng et al. 2010). Teams that are in search of new opportunities are a perfect sample of that context (Ruef 2010); this includes a new company’s foundation, which is a basic entrepreneurial act (Gartner 1988). The role of entrepreneurial teamwork is emphasized in the ideas of collective and collaborative entrepreneurship (Ribeiro-Soriano and Urbano 2009).

Cooperation is also important during times of crisis. Previous studies show that the external environment significantly influences entrepreneurial behavior and, moreover, the performance and growth of a company (Cavallo et al. 2018; Liguori et al. 2019). This includes the impact of a hostile environment (e.g., Covin and Slevin 1989). Previous research had shown that some organizations were more resilient and effective than others in terms of mastering crisis situations and the ability to adapt to new market situations during post-crisis periods (Scott et al. 2008). The challenges that were sourced in the pandemic crisis of 2020 can lead to strengthening inter-organizational cooperation – both with suppliers and customers (Duda et al. 2023). The entrepreneurs who were surveyed during the preliminary stage of this study confirmed that cooperation in the supply chain with their suppliers, customers, strategic partners, and competitors tightened, which is very rare under non-crisis conditions. Inter-organizational cooperation can play a moderating role; for example, Kim et al. (2023) revealed that inter-organizational cooperation weakens the negative relationship between family ownership and an SME’s innovativeness. Additionally, the authors observed that the moderating effect varies depending on the types of cooperative partners and activities. Martínez-Sánchez et al. (2019) found that inter-organizational cooperation moderates the relationship between external human resource flexibility and innovation. The research findings that have been published in the literature and the results of our interviews encouraged us to propose the following research hypothesis:

-

H2: Inter-organizational cooperation positively moderates the impact of EO on firm performance

2.3 Competitive behaviors

The competitive dynamics perspective has been studied extensively since its inception in the 1990s; to date, it has identified various attributes of the actions and reactions that characterize competitive behavior, including the propensity to act, reactivity, speed of execution, and visibility of actions (or reactions) (Chen and Miller 2012). Competitive propensity can be characterized by ‘aggressiveness’ (Lin and Lin 2019; Nadkarni et al. 2016), which can be specified as “the degree to which a company is likely to engage with its rivals and act quickly in its engagement” (Chen et al. 2010: 1411). Lin and Lin (2019) posited that a company with a higher propensity to compete will experience better performance. According to Lusch and Laczniak (1989: 286), a high level of competitive intensity (understood “as the strength of competitive activity in a competitive environment”) will cause companies to innovate new products to gain or maintain their market shares. Numerous studies have shown the weight of competitive intensity for generic product innovation (Kettunen et al. 2015; Lyu et al. 2022) as well as green product innovation (Chen and Liu 2019). Managers with entrepreneurially oriented attentional perspectives might concentrate more on product innovation than nonentrepreneurial managers do when the competition is greater (Andersén 2022). On the other hand, innovating new products is accompanied by the risk that generally requires firms to commit considerable numbers of resources (Alegre and Chiva 2008; Berends et al. 2014).

Competitive behaviors are perceived as one of the characteristics of entrepreneurs, and Lumpkin and Dess (1996) proposed including ‘competitive aggressiveness’ in the operationalization of EO. In the EO context, a competitive approach can lead to an increase in firm performance when it is accompanied by the presence of innovativeness and the absence of risk-taking (Kusa et al. 2022c). Competitive behaviors can play a moderating role in the EO–performance relationship (Galbreath et al. 2020; Martin and Javalgi 2016). Furthermore, Aliasghar et al. (2022) observed the moderating impact of competing on the relationship between knowledge search and process innovation among automotive component suppliers in Iran. In this study, we consider competitive behaviors to be a contradiction to the collaborative approach and propose testing their moderating roles. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

H3: Competitive behaviors positively moderate the impact of EO on firm performance

2.4 Digitalization

Digitalization is changing modern economic realities at an unparalleled rate (Kraus et al. 2021, 2022; Korherr et al. 2022). A wide variety of digital trends and technologies are forcing companies to change their business models, organizational structures, and corporate processes (Kiron et al. 2014; Bouncken et al. 2021). Digital transformation leads to the common use of new digital technologies that “enables major business improvements and influences all aspects of customers’ lives” (Reis et al. 2018: 417). Omrani et al. (2022) highlighted the relevant role of technological literacy to foster the adoption of technology for entrepreneurship. For many companies, their business depends largely on their digital capabilities (Datta and Nwankpa 2021); for SMEs, it is important to take care of their employees and ensure their work satisfaction (in addition to possessing up-to-date information technology) (Bueechl et al. 2021). Digital technologies can lead to the implementations of new products and services (EC 2018) and improve process innovation capabilities (Tajudeen et al. 2022). In turn, digital innovations can lead to increased employee satisfaction (Bueechl et al. 2021) as well as customer satisfaction (Gale and Aarons 2018) and loyalty (Balci 2021). According to Nambisan (2017), digitalization enhances individuals and enterprises to co-create and share value.

Numerous studies have shown that digital technologies are radically changing production, marketing, and consumption processes (Busca and Bertrandias 2020; Helo and Hao 2019; Klerkx et al. 2019; Teece and Linden 2017; Zhu et al. 2020). Implementing new digital technologies improves organizations’ operations (Morakanyane et al. 2017; Vial 2019) and increases their chances of competing and surviving in the market (Parra-López et al. 2021). The digital infrastructure facilitates the process of solving organizational problems in an innovative manner (Elia et al. 2020). Digital technologies create a new space for opportunities and entrepreneurial actions (Nambisan 2017) – especially during times of crisis (Rodríguez-Anton and Alonso-Almeida 2020). In a turbulent environment, digital technologies can enable dynamic capabilities and shape a firm’s business-process agility and innovativeness (Ilmudeen 2022). Digitalization creates new opportunities for entrepreneurs (Kraus et al. 2019) and leads to changes in the ways that companies work as well as in their business models (Bueechl et al. 2021). Finally, numerous studies have shown that the implementation of digital technologies positively affects company operations and performance (Teece 2018; Chatterjee et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2023).

Digitalization has been examined as a moderator in numerous studies; however, the results have been ambiguous. Kraus et al. (2023) revealed the negative moderation effect of a digitalization strategy on the relationship between EO and disruptive innovation in Italian companies. Shen et al. (2022) found that different types of digital innovation positively moderated the relationship between the adoption of digital technology and the performance of digital transformation in Chinese textile firms; the most significant moderating effect could be observed for digital innovation efficiency. Yong et al. (2022) reported the moderating role of digital technology in the relationship between the influence of internal and external stakeholder mechanisms and entrepreneurial success among entrepreneurs in Jiangsu. Based on the above arguments, we propose the following research hypothesis:

-

H4: Digitalization positively moderates the impact of EO on firm performance

2.5 Diversification

Diversification is one of the four strategies that were proposed by Ansoff (1957), who developed an enterprise development theory in the product-market setting. Many companies use diversification strategies in practice (see, e.g., Lin et al. 2020); for example, to deal with the risk of supply chain disruption (Hendricks and Singhal 2009; Whitney et al. 2014). There is evidence that diversification has a positive influence on gaining a competitive advantage (Laplume and Dass 2012; Voss and Voss 2013) and financial performance (Coudounaris et al. 2020). However, the impact of diversification on firm performance can depend on its intensity. Studies in the banking sector have shown that “moderate diversification increases a banks stability, but excessive diversification has a negative impact on its activities” (Kim et al. 2020: 94). Furthermore, the high level of diversification has a negative impact on stability (Berger et al. 2010; Gambacorta et al. 2014). Along with increasing financial liberalization and innovation, banks have sought operational diversification in order to protect themselves from global financial crises (Kim et al. 2020); however, diversification might cause a crisis, expose the bank to greater risk, and present a threat to the payment and settlement system (Wagner 2010).

Diversification is considered to be an important way to mitigate the impact of a crisis (Kusa et al. 2022a); therefore, managers diversify their businesses to build more resilient futures (HSBC 2020). In particular, diversification increases companies’ operational flexibility by having alternative suppliers and customers; they stabilize the supply and demand when disruptive events occur (Hendricks and Singhal 2009). Diversifying the supply chain during a crisis reduces risk and positively affects the performances of companies (Araz et al. 2020). Recent evidence has shown that companies that have diversified customer bases have higher streams of demand; during the COVID-19 crisis, this had an impact on increased profitability (Lin et al. 2021). Diversification can moderate the impact of EO on performance; this could be observed in Veidal and Flaten (2014) for Norwegian companies. The moderating role of diversification could also be found in Indian banks – in the context of the impact of intellectual capital efficiency on financial performance (Rani and Sharma 2023). The research findings that have been published in the literature and the results of our interviews encouraged us to propose the following research hypothesis:

-

H5: Diversification positively moderates the impact of EO on firm performance

2.6 Flexibility

Flexibility is an important element in the operations of not only large but also of small and medium enterprises. (Adomako and Ahsan 2022). Flexibility plays an important role in various business areas, including internationalization processes (e.g., Rundh 2011; Zhang et al. 2014), knowledge management (Pérez-Pérez et al. 2019), networking (Lemanska-Majdzik and Okreglicka 2019), and family businesses (Molina 2020).

In the entrepreneurial context, flexibility can include the ability to anticipate changes in the external environment; this ability enables one to prepare for such changes (Brozovic, 2018) and exploit emerging opportunities in the marketplace (Grewal and Tansuhaj 2001). Flexibility is positively associated with EO (Barringer and Bluedorn 1999; Kemelgor 2002) as well as with certain aspects of EO; for example, flexibility has a positive influence on innovation performance (Rundh 2011; Clercq et al. 2014; Chahal et al. 2019; Yu et al. 2020; Adomako and Ahsan 2022). At the strategic level, it impacts firm performance (Sen et al. 2022; Vrontis et al. 2023).

Flexibility allows an organization to adapt its strategy and operations to changes in the environment (Sen et al. 2022). This corresponds to an organization’s dynamic capabilities (Rashidirad and Salimian 2017), which are key to securing resources and improving firm competitiveness in a turbulent environment (Teece et al. 1997; Fabrizio et al. 2022); this was also visible during the pandemic crisis (Dejardin et al. 2023). For this reason, flexibility is considered to play a special role during times of crisis (Jiang and Wen 2020; Zenker and Kock 2020; Pereira-Moliner et al. 2021) – particularly enabling companies to adapt to new market conditions (Schilke 2014). Therefore, companies seek flexible resources and new capabilities to survive and then compete during a business crisis (Pereira-Moliner et al. 2021). The crisis that was caused by the COVID-19 pandemic showed that the decisive factor for the survival of many companies was the speed of responding to changes (Lee 2021). In startups, strategic flexibility plays a positive moderating role in the relationship between EO and performance (Daradkeh and Mansoor 2023). On the basis of the above, we propose the following:

-

H6: Flexibility positively moderates the impact of EO on firm performance

2.7 Role of market conditions

Previous research on entrepreneurship has highlighted the impact of the external environmental on entrepreneurial activity and its results (see, e.g., Rosenbusch et al. 2013). As stated in the introduction, hostile environments (including crises) affect entrepreneurial postures (see, e.g.Covin and Slevin 1989; Lumpkin and Dess 2001; Kraus et al. 2012; Kreiser et al. 2020; Kusa et al. 2022a). Such changes have been recently observed as a result of the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on EO (Okreglicka et al. 2021; Suder 2022; Suder 2024). However, the previous research provided evidence about both positive (this is enhancing; e.g., Martins and Rialp 2013; Dele-Ijagbulu et al. 2020) and negative (Kreiser et al. 2020) impact on EO. This ambiguity can be associated with other factors; in the entrepreneurial context, the role of firm size was confirmed (Rosenbusch et al. 2013). Market conditions can directly affect EO and performance, but they can also effect the EO–performance relationship (Wojcik-Karpacz et al. 2018; Onwe et al. 2020).

However, market conditions also affect other aspects of the activities of organizations, including collaboration, competition, diversification, flexibility, and digitalization; the review regarding our five moderators showed that their impact can change during crises. On the basis of the above, we expect that market conditions can play a decisive role regarding the moderators of the EO–performance relationship. In particular, market conditions can affect the strengths of the moderating effects and even the directions of the moderations (positive or negative). Thus, we propose the following:

-

H7: Market conditions moderate the moderations of the EO–performance relationship

2.8 Control variable

As the control variables, we employed the following statistics: the number of employees (1: 10–19 employees; 2: 20–29 employees; 3: 30–39 employees; 4: 40–49 employees); the company’s length of existence (1: 3–10 years; 2: 11–20 years; 3: more than 20 years); and the company’s location (1: rural areas; 2: small towns; 3: medium-sized cities; 4: large cities). These factors have been proposed as determinants of entrepreneurial behaviors in previous entrepreneurship studies (Lumpkin et al. 2006; Wales et al. 2013a; Real et al. 2014; Calispa Aguilar 2021). Considering the control variables may be helpful in clarifying whether the analyzed relationships between the studied variables are real (and not apparent). Since the inclusion of control variables in the model did not change the parameters of the models (in particular, the values of the path factors and their significance) when compared to those models without control variables; therefore, we ultimately did not include them in any analysis (Bernerth and Aguinis 2016).

2.9 Research model

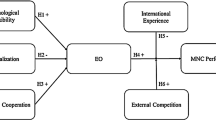

Figure 1 presents the research model. According to the above hypotheses, the moderator variables were inter-organizational cooperation, competitive behaviors, digitalization, diversification, and flexibility.

3 Methodology

3.1 Sample and data collection

This study examined small companies that represented the printing industry. At the preliminary stage of the study (June–August 2020), 25 entrepreneurs who represented several industries were interviewed. Among other things, they were asked how the crisis that was caused by the COVID-19 pandemic affected their operations. Based on the results of the interviews, the moderating variables were selected. The interviews were also used to validate the items in the research questionnaire and the constructs that reflected our variables.

Among our respondents were entrepreneurs who represented the printing industry. The Polish printing market is the largest in Central and Eastern Europe and is ranked fifth among the countries of the European Union (with annual revenues of €3.4 billion) (data from 2020; Polskie Bractwo Kawalerów Gutenberga 2020). Finally, there is one more argument for focusing on Polish companies. The Polish economy is among the fastest-growing ones (OECD 2023), and SMEs have contributed significantly to this development (Skowrońska and Tarnawa 2022). However, the entrepreneurial orientations of Polish companies are rarely examined. Despite the successful transformation of the Polish economy after 1990, data from Poland from that time had not been used in EO research until the middle of the last decade (Wales 2016); in the past years, only a few EO studies that focused on Poland were published in Scopus-indexed journals (e.g., Kusa et al. 2019, 2021; Suder et al. 2022; Wójcik-Karpacz et al. 2021, 2022).

Therefore, small printing companies that operated in Poland were selected as our target population. As of December 1, 2020, 602 such companies were evidenced in the Polish National Court Register. Ultimately, the sample was comprised of 150 small firms that had declared that printing services were their core business and that they had operated for a minimum of 3 years; this number translates to a 7% sample error (with an assumed 95% confidence level). The firms that represented the sample were surveyed with a questionnaire from December 2020 through January 2021; the data was collected by a firm that specialized in polling.

Using the parameters that were suggested by Cohen (1988, 1992) and G*Power 3.1.9.7 software (Faul et al. 2007), our analysis revealed that the statistical power of the 150-item sample was 0.986. This result surpassed the necessary threshold of 0.8, thus indicating the satisfactory statistical power of the analyzed sample.

The sample’s characteristics are presented in Table 1.

3.2 Variables

In this study, entrepreneurial orientation (EO) was an independent variable, and performance was a dependent variable; performance mainly reflected the sales outcomes of the companies. Additionally, five variables were tested as moderators; namely, inter-organizational cooperation (COOP), competitive behaviors (COMP), digitalization (DIG), diversification (DIV), and flexibility (FLEX). Each variable was a coefficient and consisted of several items; each item was measured with a five-degree Likert scale. When building the coefficients, the context of the study (the printing industry) was taken into account. Consequently, some of the coefficients were newly built, and others were adjusted on the basis of previously used indices. The performance coefficient was adopted from previous entrepreneurship research (Hughes and Morgan 2007; Kusa et al. 2021). EO is a multidimensional coefficient, and it was also adopted from previous research (Hughes and Morgan 2007). The competitive behavior index was built on the proposition from Lumpkin and Dess (1996). The inter-organizational cooperation coefficient had previously been used in entrepreneurship research (Kusa et al. 2022a). Finally, digitalization, diversity, and flexibility were newly proposed indices. The items from the constructs are presented in Appendix Table 11, and the characteristics of each index (including its reliability) are presented in Table 4; all of the indices (including those that were newly proposed) met the reliability and validity criteria (these details are presented in Section 4).

One of the objectives of the study was to examine the impact of market conditions on the relationships among EO, performance, and their moderators. The entrepreneurs from the printing industry who were interviewed during the preliminary stage of the study reported that their industry was severely affected by the crisis that was caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. This opinion was confirmed by analyses and reports on the impact of the crisis; these showed the radical change in the external environment in the printing market. These changes were sourced from the market consequences of pandemic-related restrictions; for example, the cessation of trade fairs and exhibitions (Biuletyn Wydawcy 2020) or tourist activity (Poligrafika.pl 2020). The characteristics of the printing market before and during the initial phase of the pandemic crisis are presented in Table 2.

The differences in market conditions that were indicated above exposed the need to analyze the relationships between our variables separately for the period before the pandemic crisis and during the initial phase of the crisis. Concurrently, this allowed us to test the impact of the market conditions on the examined relationships. Thus, all of the variables were assessed under two different market conditions; namely, stable (non-crisis) market conditions, and during the crisis. As the crisis that was caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was extremely dynamic, it was possible to observe radically different market conditions in just a few months of 2020. Specifically, all of the surveyed firms were asked to assess their behaviors before the COVID-19 pandemic crisis and during the first quarter of the crisis (which was characterized by deep and rapid changes in market conditions and a high level of astonishment; these required enterprises to react in extraordinary ways). Based on the data that represented different market conditions, the impact of each moderator was tested twice; this procedure enabled us to identify the impact of the market conditions on the tested moderators.

3.3 Data-analysis techniques

To identify the moderating roles of the tested variables, this study employed partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). This method is suitable for research on the moderation effects of individual variables where the amounts of data are not very large and the research is exploratory (Hair et al. 2022). In the PLS-SEM analysis, we used SmartPLS software (v. 4.0.8.7) (which was developed by Ringle et al. 2022). The impact of each moderator was tested in a separate model (this was due to the sample size, which did not allow us to construct a multi-moderator model).

In these considerations, entrepreneurial orientation was treated like a three-dimensional construct. For this reason, EO was operationalized as a second-order composite (Sarstedt et al. 2019) that was obtained in two steps using latent variable results. For this purpose, the procedure that was proposed by Wright et al. (2012) was used. This procedure required calculations for two measurement models and one structural model. This approach was used for each of the models that were considered for each period.

4 Results

The research was performed according to the procedure that was proposed by Hair et al. (2022) – taking into account the fact that the EO construct was built in two stages (Sarstedt et al. 2019).

4.1 Measurement model evaluation

In Table 3, basic information on the indicators that were used to build the construct (the mean and deviation) is presented. In addition, the indicators’ outer loadings in the measurement models could be found, as could the variance inflation factor (VIF); these allowed us to verify the occurrence of the problem of collinearity between the structural indicators.

The outer loadings of the vast majority of the indicators were well above the 0.7 threshold; this is commonly considered to be highly satisfactory for indicator reliability (Chin 2010; Ali et al. 2018). In several cases, their values ranged from 0.6 to 0.7; these were also acceptable due to their strong contributions to the substantive constructions of the constructs (Hair et al. 2022). There were no problems of collinearity in any of the constructs’ indicators. All of the VIF values were close to 3 (or lower – see Table 4), which is a highly satisfactory result for this type of analysis (Hair et al. 2022). In order to assess the validity and reliability of each construct (which was required when evaluating the measurement model) (Campbell and Fiske 1959), we followed the recommendations of Hair et al. (2018). All of the measures that were used (see Table 4) had expected values; that is, Cronbach’s alpha, the reliability coefficient, and the composite reliability were all within a range of 0.7 to 0.9, and the average variance extracted measure was greater than 0.5.

Due to the fact that EO was operationalized as a second-order construct using the latent variables that were obtained in the first stage of the analysis, the correctness of the construction of the EO construct was verified (see Table 5). All of the designated indicators and measures were at their appropriate levels.

Additionally, we calculated the VIF values for the inner models in order to detect common-method bias (CMB) (as was recommended by Kock 2015). The results (see Table 6) showed that all of the VIF values were lower than 3.3, which meant that there was no collinearity problem and that the models were free from CMBs (Hair et al. 2022; Kock 2015).

We also employed Harman’s single-factor test (as proposed by Podsakoff and Organ in 1986) to confirm the absence of problems with CMB. Given that the proportion of the total variance that was accounted for by a single factor amounted to 33.338% (the data from Period I) and 32.218% (the data from Period 2); since these were lower than the adopted threshold of 50%, it could be inferred that CMB did not affect our data. This observation confirmed that the model was free from CMB (Fuller et al. 2016).

The next stage of verifying the measurement-model constructs was to assess the discriminant validity through the Fornell-Larcker and Henseler criteria. The discriminatory validity is appropriate if the square root of the AVE of the structure is greater than its correlations with the other constructs in a model (Fornell and Larcker 1981); regarding the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT), Henseler et al. (2015) suggested a threshold value of 0.85. These conditions applied to the data that confirmed the discriminatory validity (see Table 7).

In the next step of verifying the measurement models using the standardized root square mean residual (SRMR), we investigated their fits to the data (Henseler et al. 2015). Of the 12 measurement models that were considered, 9 had SRMR values that were below 0.08 (indicating very good fits), and 3 had values that ranged between 0.08 and 0.10 (indicating good and acceptable fits) (Hu and Bentlera 1999).

At the end of the verifications of the measurement models, additional structural model evaluation criteria were determined in PLS (Hair et al. 2022) (see Table 8); these were the coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and cross-validated redundancy (Q2). These measures allow one to assess the predictive capabilities of any considered model (Falk and Miller 1992; Cohen 1988).

After analyzing the R2 values, we concluded that the levels of the explanations of the variances of performance ranged from 35.1 to 51.5% (depending on the model and period); these results were satisfactory in the context of research in the social sciences (Falk and Miller 1992). When comparing the values of the coefficients of determination for the two considered periods, slight differences in their values were noticeable for the individual models (the greatest difference occurred for Model 5 and equaled 7.2% points).

According to Cohen (1988), the thresholds for the effect size (f2) values (which evaluated the magnitudes of the changes in the R2 values when the exogenous variables were omitted) were 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35; these represented small, medium, and large effects, respectively. However, it was assumed that these thresholds were too strict for the moderation effect (Kenny 2016), so these were set at the following respective levels: 0.005, 0.01, and 0.025.

The obtained values of the f2 values for the EO variable were greater than 0.15 for ten of the models; these indicated the medium or large influence of this variable on the result variable. The effect size for the EO variable was only assessed as being low in the case of Model 4. The direct impact of the considered variables (COOP, COMP, DIG, DIV, FLEX) were at low levels in most of the cases; the exceptions were diversification in both periods and digitalization during the crisis (in which the effects were defined as being medium) as well as flexibility during the crisis (for which no effect was obtained). When assessing the effect size values for the variables with moderators, we used the thresholds that were proposed by Kenny (2016). Table 8 shows that, for the models in Period 1, weak effects were obtained for three exogenous variables (COOP, COMP, and DIG), no effect was obtained for DIV, and a medium effect was obtained for FLEX. However, the situation was slightly different in the models for Period 2; namely, large effects were obtained for COOP, DIG, and DIV, while a small effect was obtained for COMP and no effect was obtained for FLEX. Thus, the results of this stage of the analysis confirmed the fact that the selected exogenous constructs with moderators presented the greater importance in explaining the variability of the endogenous variables in the cases of the models for the crisis data.

Based on the values of the Q2 statistic (whose values were definitely greater than 0 in all of the models), we could unequivocally state that the considered exogenous constructs had a predictive meaning for the endogenous variables (Stone 1974).

4.2 Hypothesis verification

Using structural models, we tested the hypotheses and assessed the significance of the path coefficients for each of the considered models. By using bootstrapping with 5000 sub-samples, it was possible to verify the significance of the obtained path ratios for the measurement models. The significance verification was performed in two ways: first, the test statistics were determined, and the test probability values were obtained on the bases of these (when verifying the hypotheses, the standard 5% significance level was assumed); second, we also calculated the confidence interval bias corrected (following Ramayah et al. 2018). If this interval contained 0, this indicated that the determined factor of a given path in the model was not significant. Two-tailed tests were used to verify all of the hypotheses. The results of the analyses are presented in Fig. 2; Table 9.

Due to the main goal of the study (that is, a comparison of the modeling results from two periods [different in terms of market conditions] with a particular emphasis on the impact of EO on PERF and the strength of the moderation effects), the results that are contained in Fig. 2; Table 9 will be mainly discussed in this context.

The results of the SEM-based analysis confirmed our Hypothesis H1. Specifically, EO positively and significantly affected a firm’s performance under both non-crisis and crisis conditions in each tested model (in the direct model, and in the moderation models regardless of the moderator). All of the path coefficients for the impact of EO on PERF were found to be statistically significant, and the confidence interval bias corrected for the EO→PERF paths did not contain 0. The differences in the strengths of the impact of EO on PERF in the main model, which was the most reliable in the study of this relationship, were negligible (before the crisis, this was 0.616; during the crisis, it was 0.593).

According to our results (see Fig. 2; Table 9), the positive moderation (positive path coefficients) of EO’s impact on PERF occurred in the cases of COOP, DIV, and FLEX during the pre-crisis period (the greatest impact was found for FLEX – 0.088). However, the moderator effects were not significant. In the cases of COMP and DIG, the path factors for the moderating effect were negative (but also not statistically significant). Therefore, Hypotheses H2–H6 were not confirmed for Period I. For the crisis period, these results were slightly different; that is, the path coefficients for the moderation effects were greater than 0 for all of the models (suggesting the positive impact of the moderators on the EO→PERF relationship). The highest coefficient value was obtained for cooperation (0.146), and the lowest was found for flexibility (0.027). However, only three out of the five tested moderators were significant; these were inter-organizational cooperation, digitalization, and diversification. This observation confirmed our Hypotheses H2, H4, and H5 for Period II; Hypotheses H3 and H6 (referring to competitive behaviors and flexibility, respectively) were not confirmed for Period II.

To illustrate the moderation effects and further validate the previous findings, simple slope analyses are presented in Fig. 3 (Aiken and West 1991). Each graph depicts three lines that represent the relationships between EO and company performance (PERF) depending on the moderator, with the middle (blue) line symbolizing the relationship at an average level of each moderator. The upper (green) line illustrates the EO→PERF relationship for those moderator values that increased by one standard deviation, while the lower (red) line illustrates this relationship for those moderator values that decreased by one standard deviation. Parallel lines indicate no moderation effect, while the divergence of lines (widening with increasing EO) suggests a positive moderation, thus reinforcing the effect. On the contrary, a convergence of lines indicates negative moderation, which shows a weakened effect. In our results (see Fig. 3), the lines are parallel or slightly converged for Models 1–4 for Period I, indicating no moderation (or a weak insignificantly negative one). In the case of FLEX, the lines diverge slightly, suggesting a positive moderation; however, this moderation was not statistically significant (as was revealed in the earlier analysis – see Table 9).

The results of a simple slope analysis for the data from the crisis period confirmed and reinforced the previous findings on the moderating effects. Specifically for Models 1, 3, and 4, significant line divergences can be observed, thus confirming the earlier conclusions about the moderating roles of COOP, DIV, and DIG for Period II. A noticeable deviation from line parallelism can also be observed for the COMP moderator, indicating that this variable also strengthened the influence of EO on PERF for Period II (although this moderation was not statistically significant – see Table 9). In the case of FLEX, the corresponding graph in Fig. 3 clearly indicates the lack of a positive moderation.

The simple slope analysis allows one to interpret the path coefficients for the moderation effects. In Model 1 for Period II, for example, the strength of the impact of EO on PERF is expressed by a coefficient of 0.518 (the slope of the blue line). For a higher level of COOP, this coefficient increased by the moderation effect path coefficient (which was 0.146). Therefore, the slope of the green line was determined by adding 0.518 and 0.146 (totaling 0.662). This implies that, with a higher value of the COOP variable, the impact of EO on PERF is stronger, thus reflecting the essence of a positive moderation effect.

4.3 Role of market conditions (post-hoc test)

The conclusions that were drawn from the earlier analysis allowed for a preliminary verification of Hypothesis H7 concerning the moderating role of market conditions as related to the considered moderators. The compilation that is presented in Table 10 enables one to identify those conditions under which the moderating effect was significant and under which it was not (in relation to the individual moderators). There are indications that the moderating effect of market conditions applied to such moderators as COOP, DIG, and DIV.

However, the fact that one path coefficient was significant while the other was not does not necessarily mean that the differences between them were statistically significant. To confirm the moderating role of market conditions and compare the strengths of the considered effects, it was therefore verified whether the path coefficients for the moderating effects differed significantly from each other during the individual periods. For this purpose, the Welch-Satterthwait (W-S) test (Sarstedt et al. 2011) was used, which allowed us to verify whether the differences between the path coefficients for the moderating effects during the different periods were different from 0. The results of the test (presented in Table 9) largely confirmed the previous findings.

In particular, the moderating effect for Period II proved to be significantly greater than for Period I for DIG and DIV (see Table 9); this fully confirmed the previous conclusions and, consequently, Hypothesis H7 for these moderators. The results of the W-S test were also consistent with the findings regarding FLEX. Our earlier conclusions suggested the lack of a moderating effect for FLEX. The results of comparing the path coefficients (as presented in Table 9) indicated that they were not significantly different, providing empirical evidence of the lack of a confirmation of Hypothesis H7 for FLEX.

For COOP and COMP, the results were inconclusive. In the case of COOP, the moderating effect was significant for Period II yet not significant for Period I; however, the differences in the strengths of the moderating effects between the two periods was not statistically significant (as indicated by the data in Table 9). Consequently, it can be stated that there was a partial confirmation of Hypothesis H7 regarding COOP; this suggests the need for further verification in subsequent studies.

For COMP, the situation was reversed; namely, this moderating effect did not prove to be statistically significant for either period. However, the results of the W-S test led to the conclusion that the reinforcement of COMP during the initial phase of the pandemic (Period I) significantly strengthened the impact of EO on PERF when compared to the stable period (pre-pandemic). Therefore, the empirical results did not provide a clear answer in the context of verifying Hypothesis H7 for COMP.

5 Discussion and contribution to literature

This study contributes to the ongoing discourse that surrounds the relationship between EO and performance as well as the moderators of this relationship; also, the role of the external environment is explored in the context of EO. Being conducted on small businesses in the printing industry in Poland, the research focused on examining whether the selected variables (namely, inter-organizational cooperation, competitiveness, digitalization, diversification, and flexibility) act as moderators on the relationship between EO and performance. What distinguishes this study from others is its unique approach – investigating data from two distinct market conditions; namely, pre-crisis (Period I), and during the crisis (Period II). This approach allows us to set market conditions as a moderator for each of the considered moderating effects. By amalgamating the two prevalent approaches in the literature, this research consequently becomes innovative and fills a significant research gap – one that is related to examining moderating effects on the EO–PERF relationship under various market conditions.

Our results showed that market conditions significantly modify the roles of inter-organizational cooperation, digitalization, and diversification; in particular, a change in market conditions (e.g., the outbreak of the crisis) activates them as moderators of the EO–performance relationship. These observations advance our understanding of the adaptation of a firm to a new market situation (Scott et al. 2008). The findings confirmed the previous research on the impact of the external environment on entrepreneurial behavior and its relationship with performance (e.g., Cavallo et al. 2018; Liguori et al. 2019) – especially in regard to a hostile environment (e.g., Covin and Slevin 1989; Rosenbusch et al. 2013; Dele-Ijagbulu et al. 2020; Suder 2022). The evidenced role of market conditions suggests that, when analyzing the moderating roles of other factors, we should consider that their roles can be moderated by market conditions. With this finding, the study contributes to the literature on organizational strategies and entrepreneurship. Taking the increasing variability of the external environment into account, an in-depth understanding of the moderating role of market conditions toward the determinants of performance gains importance.

Furthermore, this study contributes to the literature on several organizational characteristics that affect firm performance as well as firm strategy and entrepreneurship in a wider perspective. The obtained results showed that, for some entrepreneurial behaviors, market conditions are an important factor in terms of their moderating role on the EO–performance relationship. In particular, the obtained results for some of the considered behaviors (i.e., DIG and DIV) were unequivocal. Namely, the analyses showed that, for DIG and DIV, their moderating powers (which were insignificant during the pre-pandemic period) significantly increased during the unstable period; they reached such a level that they played significant roles in strengthening the impact of EO on performance.

The positive impact of digitalization on the EO–performance relationship under crisis conditions supports previous evidence that many businesses depend on digital capabilities (Datta and Nwankpa 2021) and that digital technologies positively affect their operations and performance (Teece 2018; Chatterjee et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2023). However, our research brings new light to these observations, as it has shown that digitalization’s role as a moderator is not significant under non-crisis conditions; under crisis conditions, however, it becomes a moderator of the EO–performance relationship. The increasing role of digitalization during a crisis confirms the observations from the previous studies that showed that innovation and digitalization could stimulate entrepreneurial actions – especially during times of crisis (Rodríguez-Anton and Alonso-Almeida 2020) and could lead to changes in business models during times of crisis (Rodríguez-Anton and Alonso-Almeida 2020; Bueechl et al. 2021). This explains the mechanism behind the strengthening of the survival chances among those firms that implement digital technologies (Parra-López et al. 2021). The findings on the role of digitalization are highly relevant to the growing literature on digitalization in an organizational context.

Our findings on the moderating role of diversification were in line with those studies that indicated that a diversification strategy had a positive impact on firm performance (Coudounaris et al. 2020) and competitive advantage (Laplume and Dass 2012; Voss and Voss 2013). The results showed that diversification is not a significant moderator of the EO–performance relationship under non-crisis conditions but is a vital moderator under crisis conditions. This observation confirmed the previous evidence on the positive impact that diversification had on the operations and developments of banks during the recent financial crisis (Baele et al. 2007) as well as the stream of demand and level of profitability during the COVID-19 crisis (Lin et al. 2021). The findings on the changing role of diversification in the EO context add value to the literature on strategic management, where diversification has been a subject of research for decades.

For inter-organizational cooperation, the results were inconclusive in terms of the impact of market conditions on their moderating roles. In particular, the strength of inter-organizational cooperation’s moderating effect increased enough to become statistically significant with the onset of the crisis (even though it was not significant before the pandemic). The observation that the impact of inter-organizational cooperation on the EO–performance relationship was significant during the crisis was in line with those papers that argued that cooperation had a positive effect on company operations (e.g., Sitawati and Winata 2018; Pavlova 2019) and performance (Zeng et al. 2010; Kusa et al. 2022a). However, our findings bring new light to the research on the impact of collaboration on company performance, as we have shown that, even though cooperation significantly affects performance, it is not an important moderator under non-crisis conditions but is under crisis conditions. Along with the observed absence of the moderating impact of competitive behaviors, this study contributes to the literature on inter-organizational relationships and the discussion on the role of inter-organizational cooperation and competition (which remains one of the most important strategic dilemmas).

In the sample that was examined in this study, the moderating roles of flexibility and competitive behaviors were also not significant (neither before nor during the crisis). Therefore, this study did not confirm the previous research that indicated the positive moderating role of flexibility in the relationship between EO and performance (as was reported by Daradkeh and Mansoor 2023). Moreover, this was somehow in contradiction to those previous studies that suggested associations between flexibility and EO (Barringer and Bluedorn 1999; Kemelgor 2002) as well as between flexibility and firm performance (Sen et al. 2022; Vrontis et al. 2023). It also contradicted those studies that highlighted the role that is played by flexibility during times of crisis (Jiang and Wen 2020; Zenker and Kock 2020; Pereira-Moliner et al. 2021). In the case of flexibility, the strengths of the moderating effect were not significantly different for both of the considered periods; thus, market conditions are irrelevant in regard to the moderating role of flexibility in the EO–performance context. Regarding competitive behaviors, there was a significant increase in the strength of the moderating effect for the second period; as mentioned before, however, this was not large enough to become statistically significant. This result was difficult to interpret in the context of the impact of external conditions (a significant change in an insignificant impact). The lack of a significant association between competitive behaviors and EO was surprising in light of their position in the literature on EO where Lumpkin and Dess (1996) proposed interpreting ‘competitive aggressiveness’ as one of the dimensions of EO. Similarly, numerous studies have shown the association between competitive behaviors and performance (e.g.Lin and Lin 2019; Kusa et al. 2022c), which was not observed in this study. The absence of the moderating effect of competitive behaviors in the EO–performance relationship was contrary to the studies by Martin and Javalgi (2016) and Galbreath et al. (2020). The observations on flexibility and competitive behaviors add arguments to the discussion on firm strategy wherein these factors are considered.

Finally, our study joins the research stream that is focused on clarifying inconsistencies regarding the relationship between EO and organizational performance (Real et al. 2014; Wales 2016). Our findings supported the evidence that EO positively and strongly impacts firm performance (e.g., Covin and Slevin 1991; Miles et al. 1978; Teece 2017; Wales et al. 2013a, b; Zahra 1993; Peters and Waterman 1982). In particular, the results confirmed those observations from the previous research regarding the impact of EO on the performance of SMEs (e.g., Sidek and Mohd Rosli 2021; Isichei et al. 2020). This study confirmed that EO impacts performance under both non-crisis and crisis conditions; however, our results shed new light on those studies that have indicated low or insignificant correlations between EO and organizational effectiveness (e.g., Andersen 2009; Rauch et al. 2009; Renko et al. 2009) or that have shown mixed or non-linear relationships between EO and organizational performance (e.g.Rezaei and Ortt 2018; Wales et al. 2013b). Namely, our research confirmed the previous findings that this relationship could be moderated by other factors (e.g., Tang et al. 2008) under specific market conditions (e.g., Lomberg et al. 2017). However, the impact of moderating factors vary depending on market conditions (non-crisis and crisis) – this can be helpful when explaining the non-linearity of the relationship. The activation of several moderators suggests that, under crisis conditions, the EO–performance relationship becomes more fragile and can be affected by other factors (which were not in a position to impact the EO–performance relationship before the crisis – when this relationship was strong and independent of any factors). The observations that were presented above contribute to the rich literature on EO and its impact on firm performance and helps explain some inconsistencies regarding this impact by specifying the roles of its moderators and the relationships among them (in particular, the meta-moderating role of market conditions).

By showing that the crisis affected the impact of some factors on the relationship between EO and performance and indicated the factors that became efficient during the crisis, the study contributes to the literature on crisis management. Furthermore, the findings contribute to the emerging field of research on entrepreneurial resilience (Branicki et al. 2018; Lafuente et al. 2019), whose development has been accelerated since the COVID-19 pandemic; in this line, EO (along with our moderators) can be tested as a determinant of firm resilience in future studies. Finally, the above-mentioned findings contribute to small business research by providing evidence that reflects the investigated relationship in SMEs, as the examination was focused on small firms.

6 Conclusions

The findings of this study contribute to scholarship in several areas, including organizational entrepreneurship and strategic management as discussed in light of the literature. Furthermore, this examination contributes to the research methodology by exemplifying the procedure for examining double-level moderation. In addition to contributing to the literature, the findings of the study are a source of managerial implications; they show how SMEs can improve their performance under certain conditions and how policymakers can modify their strategies for the industrial sector. In particular, the findings show that entrepreneurs can enhance their performance by developing inter-organizational cooperation, digitalization, and diversification – even if these factors had been perceived as being irrelevant before the crisis. During a crisis, these factors can leverage the impact of entrepreneurial behaviors on performance (in addition to their potential direct impact on performance). In an environment that increases its variability, such levers are especially valuable. This also indicates that policymakers should consider shaping the legal and economic environment that facilitates inter-organizational cooperation and encourages enterprises to digitalize and diverse their activities – these directions were accurate during the last crisis that was caused by the pandemic.

The study has some limitations. First, the sample was limited to small firms that represented one industry and one country. Despite the fact that EO has an impact on performance regardless of where a firm is located (Rauch et al. 2009), the roles of the examined moderators can vary across countries. Additionally, the observed relationships can be specific for a particular industry to some extent. Second, the data-collection procedure should be considered to be a limitation. In particular, we collected data that referred to company behavior under different market conditions for one survey; this required the respondents to perform retrospective assessments (we asked our respondents for their assessments, which referred to different situations that had occurred more than ten months before) – this could have resulted in both overestimations and underestimations of the examined factors. Third, the study investigated the impact of various market conditions that were triggered by the pandemic crisis. This type of crisis differed from other types (e.g., financial crises); consequently, those moderators that are active during a crisis of another type may differ from those that were triggered by a pandemic crisis (observed in the study). Fourth, this study examined only five moderators – these did not represent all of the factors that could affect the relationship between EO and firm performance (especially if we consider industry-specific factors). Finally, we were unable to test all of the variables within one model due to the sample size; this prevented us from identifying any possible interferences among the tested moderators. These limitations indicate several directions for future studies; in particular, the study can be replicated in other contexts (country, industry, company size, crisis) and include other moderators – this would enhance our understanding of those factors that affect firm performance and the EO–performance relationship.

The findings of this study provided new insights into the relationship between EO and performance. First, the findings confirmed that EO positively and strongly impacts firm performance, regardless of market conditions (i.e., under both non-crisis and crisis conditions). Second, this study unveiled the moderating role of inter-organizational cooperation, digitalization, and diversification; these factors positively moderated the impact of EO on performance (albeit only under crisis conditions). And third, the implemented research procedure (namely, the collection of data that referred to two different periods) enabled a comparison of the examined models under two different market conditions (non-crisis and crisis). This allowed us to prove the impact of market conditions in the context of organizational entrepreneurship. In particular, market conditions influence the role of inter-organizational cooperation, digitalization, and diversification as moderators in the relationship between EO and performance (in particular, they only become moderators during a crisis). Thus, it can be concluded that market conditions can moderate other moderators in the context of the EO–performance relationship.

Data availability

This manuscript has no associated data.

References

Abu-Rumman A, Al Shraah A, Al-Madi F, Alfalah T (2021) Entrepreneurial networks, entrepreneurial orientation, and performance of small and medium enterprises: are dynamic capabilities the missing link? J Innov Entrep 10:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-021-00170-8

Adamowicz E (2021) Gospodarka w czasie pandemii (The economy during the pandemic). Gazeta SGH. https://gazeta.sgh.waw.pl/meritum/gospodarka-w-czasie-pandemii. Accessed July 2023

Adomako S, Ahsan M (2022) Entrepreneurial passion and SMEs’ performance: moderating effects of financial resource availability and resource flexibility. J Bus Res 144:122–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.02.002

Aiken LS, West SG (1991) Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage, Newbury Park

Alegre J, Chiva R (2008) Assessing the impact of organizational learning capability onproduct innovation performance: An empirical test. Technovation 28(6):315–326

Alexiev AS, Volberda HW, Van den Bosch FAJ (2016) Interorganizational collaboration and firm innovativeness: unpacking the role of the organizational environment. J Bus Res 69(2):974–984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.09.002

Ali F, Rasoolimanesh SM, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Ryu K (2018) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 30(1):514–538

Ali A, Aima A, Bhasin J, Hisrich RD (2021) Measuring entrepreneurial orientation in developing economies: Scale Development and Validation. Jindal J Bus Res 10(2):147–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/22786821211045178

Aliasghar O, Rose EL, Asakawa K (2022) Sources of knowledge and process innovation: the moderating role of perceived competitive intensity. Int Bus Rev 31(2):101920

Andersen J (2009) A critical examination of the EO-performance relationship. Int J Entrep Behav Res 16(4):309–328

Andersén J (2022) An attention-based view on environmental management: The influence of entrepreneurial orientation environmental sustainability orientation and competitive intensity on green product innovation in Swedish small manufacturing firms. Organization Environment ,1–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/10.860266221101345

Ansoff HI (1957) Strategies for diversification. Harv Bus Rev 35(5):113–124

Anwar M, Clauss T, Issah WB (2022) Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance in emerging markets: the mediating role of opportunity recognition. RMS 16:769–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-021-00457-w

Araz OM, Choi TM, Olson D, Salman FS (2020) Data analytics for operational risk management. Decis Sci 51(6):1316–1319

Baele L, De Jonghe O, Vander Vennet R (2007) Does the stock market value bank diversification? J Bank Finance 31(7):1999–2023

Balci G (2021) Digitalization in container shipping: Do perception and satisfaction regarding digital products in a non-technology industry affect overall customer loyalty? Technol Forecast Soc Change 172:121016

Banchuen P, Sadler I, Shee H (2017) Supply chain collaboration aligns order-winning strategy with business outcomes. IIMB Manage Rev 29:109–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2017.05.001

Barringer BR, Bluedorn AC (1999) The relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and strategic management. Strateg Manag J 20:421–444

Bartik AW, Bertrand M, Cullen Z, Glaeser EL, Luca M, Stanton C (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proc Natl Acad Sci 117(30):17656–17666

Basco R, Hernandez-Perlines F, Rodríguez-García M (2020) The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on firm performance: a multigroup analysis comparing China Mexico and Spain. J Bus Res 113:409–421

Berends H, Jelinek M, Reymen I, Stultiëns R (2014) Product innovation processes in small firms: Combining entrepreneurial effectuation and managerial causation. J Prod Innov Manage 31(3):616–635

Berger AN, Hasan I, Zhou M (2010) The effects of focus versus diversification on bank performance: evidence from Chinese banks. J Bank Finance 34(7):1417–1435

Berggren B, Olofsson C, Silver L (2000) Control aversion and the search for external financing in Swedish SMEs. Small Bus Econ 15(3):233–242. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1008153428618

Bernerth JB, Aguinis H (2016) A critical review and best practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers Psychol 69(1):229–283

Bhaskara GI, Filimonau V (2021) The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational learning for disaster planning and management: a perspective of tourism businesses from a destination prone to consecutive disasters. J Hosp Tour Manage 46:364–375

Biuletyn Wydawcy (2020) Polska poligrafia podczas pandemii – wyniki ankiety (Polish printing during the pandemic – survey results). https://wydawca.com.pl/2020/05/19/polska-poligrafia-podczas-pandemii/. Accessed July 2023

Bouncken RB, Plüschke BD, Pesch R, Kraus S (2016) Entrepreneurial orientation in vertical alliances: joint product innovation and learning from allies. RMS 10:381–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-014-0150-8