Abstract

Technical efficiency in banking is a critical aspect of the financial industry and has been widely studied using various measurement techniques. This systematic literature review offers a comprehensive examination of 305 studies on the application of technical efficiency measurement techniques in both Islamic and conventional banking sectors from 1989 to 2019. Our comprehensive analysis not only provides a broad view of the efficiency measurement literature but also outlines a future research agenda. Despite the extensive research in this field, several issues remain unresolved, including input–output selection, a comparison of efficiency between Islamic and conventional banks, limited cross-country studies, and a lack of exploration into the impact of regulation and Shariah principles. To address these gaps, this review highlights the most commonly used methods, variables, and findings and provides three key recommendations for future research. Three key themes emerge from our examination. First, there is a need to better understand and the application of new frontier techniques other than the traditional methods, which currently dominate the existing literature. Second, the intermediation approach is the most frequently used in variable selection, thus more studies with comparative findings with applications of production and value-added approaches are suggested. Third, the most frequently used input variables are ‘labor’, ‘deposits’ and ‘capital’, whilst ‘loans’ and ‘other earning assets’ are the most popular output variables. We recommend three vital directions for future research: (i) non-interest expenses to be included amongst the inputs, while non-interest income should be added to the list of outputs, especially when estimating efficiency scores of Islamic banks. (ii) The impact of environmental variables such as, inter alia, Shariah principles, country-specific factors, and management quality is suggested to be considered simultaneously in models measuring and comparing the efficiency of Islamic and conventional banks. (iii) The selection of performance metrics employed should be expanded to include both the standard efficiency scores and the Malmquist Total Factor Productivity Index (TFP). The paper concludes with research needs and suggests directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The study of bank efficiency is central to the growth and long-term sustainability of the banking sector (Chen et al. 2021; Ghosh et al. 1994; Ramly et al. 2017), and there has been an abundance of research on the topic (Abreu et al. 2019; Aliyu et al. 2017; Bhatia et al. 2018; Jiang et al. 2020; Lopes et al. 2021; Rahman et al. 2021; Shaikh and Memon 2021). Given the large volume of literature on this subject and the ongoing expansion of research, it is imperative to evaluate the recent advances and current state of knowledge in this field (Zhu et al. 2021). The objective of this study is to bridge a research gap by conducting a critical review of recent technical efficiency methods applied to both Islamic banks (IBs) and conventional banks (CBs). This review seeks to elucidate patterns and trends in the field, as well as identify the key factors that influence efficiency. Furthermore, this study aims to provide a roadmap for future research in this area.

Islamic finance has grown tremendously over the last decade, with Islamic banking being the largest segment of the industry, accounting for 71% of the global Islamic finance assets and 6% of global banking assets (Mordor Intelligence 2021). In 2017, there were 505 Islamic banks, including 207 Islamic banking windows, and the Islamic banking assets comprised 28.8% of the total assets in Asia, 42.3% in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), 25.1% in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), 0.8% in Africa, and 3.5% in other countries. Iran (32.1%) and Saudi Arabia (20.2%) held the highest shares of the global Islamic banking assets, followed by Malaysia (10.8%), United Arab Emirates (UAE) (9.8%), Kuwait (6.3%), and Qatar (6.2%) (Islamic Financial Services Industry Stability Report 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic impacted the growth of the Islamic finance markets, with Sukuk being the most affected sector (Mordor Intelligence 2021).

The rapid growth of Islamic banking has been attributed to the continuing interest of policymakers and regulators around the world (Yilmaz and Gunes 2015). However, a direct comparison between IBs and CBs should be approached with caution, as the two groups may differ significantly in their goals and operational circumstances (Khan 1986; Khan and Mirakhor 1987; Dar 2003). The technical efficiency of banks has been analyzed in the literature using various parametric and non-parametric frontier techniques, as well as accounting ratio analysis (Jarboui 2016; Mahajan et al. 2020; Sellers-Rubio and Más-Ruiz 2015; Wang et al. 2015, 2021; Wijesiri et al. 2019). Although each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages, frontier approaches are generally considered to be superior to standard financial ratio analysis as they are equipped with statistical tools (Iqbal and Molyneux 2005). However, there is no consensus in the literature on the best technique or on the selection of input–output variables, and no agreement on the sources of differences in efficiency scores.

To address the current research gaps and provide guidance to researchers, we conducted a systematic literature review of 18,461 articles on bank efficiency measurement. The review aims to identify the most commonly used variables, countries of focus, empirical methods, and research gaps in the technical efficiency of IBs and CBs, with a focus on the impact of scale efficiency, environmental variables, innovative methods, and selected variables. Our systematic literature review is based on the screening of articles from seven prestigious journals listed in various databases. This review is unique in that it synthesizes studies that applied both parametric and non-parametric frontier techniques, as well as accounting ratios, to measure bank efficiency.

Despite that there are literature review papers published on bank efficiency measurement (e.g., Abreu et al. 2019; Aliyu et al. 2017; Bhatia et al. 2018; Hassan and Aliyu 2018; Lampe and Hilgers 2015; Liu et al. 2016; Sharma et al. 2013), they are either mainly focusing on (i) efficiency and/or productivity measurement with an application of DEA and/or SFA disregarding the other methods applied or (ii) reviewing applications on Islamic or conventional banks independently. This paper is unique in this respect in that it introduces a synthesis of studies that applied parametric and non-parametric frontier techniques as well as accounting ratios to measure technical efficiency scores of Islamic and conventional banks.

Considering the application of the systematic literature review technique, this paper provides an in-depth review as a product of screening 18,461 research articles from prestigious journals listed on seven databases. Moreover, we aim to identify the most popular input–output variables in the existing bank technical efficiency literature, help address the research gaps by offering critical reflections and propose suggestions for future research. We, thus, classify bank efficiency measurement studies into six categories as follows: (i) regulation in IBs as Shariah principals; (ii) stability; (iii) scale efficiency; (iv) input/output variable selection; (v) methods to incorporate environmental variables into the analysis, and (vi) technical efficiency measurement of Islamic and/or conventional banks.

Our paper makes several noteworthy contributions to the existing literature on technical efficiency measurement in the Islamic and conventional banking sectors. First, we provide a comprehensive and up-to-date review of the recent literature, spanning an extensive 30-year period from 1989 to 2019. Through this rigorous review, we systematically identify and synthesize key findings, revealing gaps in the literature that warrant further investigation. Second, we elucidate significant divergences in the efficiency measurement techniques utilized in the literature, underscoring the need for standardized evaluation methods. By emphasizing these areas of divergence, we advance the understanding of technical efficiency evaluation and provide a foundation for future research directions and collaborations across diverse banking systems and countries. Third, we shed light on the crucial role played by specific environmental factors, including Shariah principles, stability, and economies of scale, in shaping efficiency outcomes. By incorporating both standard efficiency scores and the Malmquist Total Factor Productivity Index (TFP), our study offers valuable insights for policymakers and researchers seeking to comprehensively evaluate and compare the performance metrics of Islamic banks with their conventional counterparts. In an attempt of evaluating the efficiency scores of IBs and CBs in numerous countries, researchers investigated the main drivers of efficiency disparities among these groups of banks. Therefore, we structured this study in a way that identifies the factors that need more investigation for future research. Although recent research has extended the investigation of bank technical efficiency to include the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, we have deferred this topic for a future literature review paper. Our decision is informed by the period of study in this paper, which focuses on the years spanning 1989 to 2019, immediately preceding the onset of the pandemic.Footnote 1

We argue that technical efficiency is a vital area to study as banks that are technically efficient are able to produce more outputs for a given level of inputs, such as labor, capital, and technology. This can help them reduce costs, increase profits, and remain competitive in the market. Some reasons to review technical efficiency studies in banks are as follows. First, the banking industry is highly regulated, and banks are often required to meet certain standards of efficiency in order to maintain their licenses and operate in the market. Second, banks operate in a highly competitive environment, and efficiency can be a key factor in determining which banks survive and thrive in the market. Third, the financial crisis of 2008 highlighted the importance of efficiency in banking, as many banks were found to be operating inefficiently and taking on excessive risks.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 introduces the research framework of the study, followed by the research method in Sect. 3, in which the selection criteria of the listed studies are explained. Section 4 reviews the existing literature on efficiency measurement methods identifying the main factors of the analysis and commonly used variable selection approaches. Section 5 highlights the main research gaps and areas for future research and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Research framework

The COVID-19 pandemic has precipitated profound changes across the global economy, significantly impacting the banking sector. A substantial transition towards digital banking, alterations in customer borrowing and lending behavior, and the advent of new regulatory policies mark the sector's evolving landscape. This has consequently triggered an increasing interest in assessing the technical efficiency of banks during the pandemic period. Notably, research by Al Mamun et al. (2021) and Bele et al. (2021) has explored this in Bangladesh and Nigeria, respectively, revealing a significant negative impact on banks' technical efficiency. Complementing this perspective, recent studies have furthered the understanding of this situation. For example, Boubaker et al. (2022) scrutinized the efficiency of 49 Islamic banks across ten countries during the pandemic, showing how input reduction could maintain efficiency amidst decreasing outputs. In addition, Shah et al. (2021) provided a comprehensive review of Islamic bank efficiencies, signifying the influence of variable choices and regional factors on efficiency, particularly during crises. Boubaker et al. (2023) elaborated on how Islamic banking, with its trade-off between reducing credit risk and increasing business risk due to higher operational costs, has contributed to banking sector fluctuations. Finally, Mateev et al. (2022) underscored the importance of efficiency and market competition in the performance of banks during the pandemic, emphasizing regulatory reforms that bolster efficiency to counter adverse impacts. While the present paper concentrates on the 1989–2019 period, we acknowledge the potential impact of the pandemic on bank technical efficiency. However, given the ongoing pandemic and limited data availability, it is premature to present conclusive results. The examination of the pandemic's impact on bank technical efficiency will, thus, be a focus of our future research.

This paper examines the literature on technical efficiency in Islamic and conventional banks from 1989 to 2019, using Tranfield et al.'s (2003) guidelines for conducting a systematic literature review. The analysis involves five steps: (1) Defining the topic and relevant keywords by exploring significant contributions to the subject and identifying selection criteria. (2) Conducting searches on seven scientific databases (JSTOR, Elsevier’s Science Direct, Springer, Oxford Publishing, SCOPUS, Emerald Insight, and Wiley) for the terms ‘bank efficiency’, ‘Islamic banks’, and ‘conventional banks’ in combination with ‘parametric’ or ‘non-parametric’, with the search term ‘bank efficiency’ complementing terms like ‘bank performance’ and ‘bank profitability’ to obtain more relevant search results that cover studies using accounting ratios for bank efficiency measurement. (3) Screening and eliminating duplicates from the remaining articles and verifying their conformity to the pre-defined selection criteria; we developed a coding system, following Gough (2007), at this stage to ensure consistency among the two authors reviewing the data. (4) Examining the abstracts of all remaining articles for consistency with the selection criteria. (5) Following the review process of all remaining full papers in the dataset by the authors of this paper, we received third feedback from an academic scholar who has been in the research field of technical efficiency measurement over 25 years. (6) Creating summary tables accordingly. Table 1 summarizes the inclusion criteria, while excluding corporate governance, risk-adjusted efficiency, venture capital, management accounting, productivity measurement, hedging, joint ventures, managerial efficiency, and theoretical papers.

3 Research method

3.1 Databases and search results

A total of 18,461 articles in English were listed in the seven scientific databases specified, namely JSTOR, Elsevier's Science Direct, Springer, Oxford Publishing, SCOPUS, Emerald Insight, and Wiley. The use of multiple databases aims to avoid publication bias and ensure a comprehensive literature review. JSTOR is considered one of the most relevant databases for social sciences, according to George State University Library. Meanwhile, Scopus is the largest abstract and citation database of multidisciplinary peer-reviewed literature search, introduced by Elsevier Science in 2004, and is considered the best database as an alternative to Web of Science (WOS) in social sciences in terms of coverage, according to Norris and Oppenheim (2007). Moreover, Vieira and Gomes (2009) found that Scopus covers 20% more research than WOS. Consequently, this paper focused mainly on Scopus and Elsevier's Science Direct, rather than WOS. Additionally, Springer and JSTOR were observed to index a significant number of publications on bank efficiency measurement. Table 1 summarizes the number of papers identified in each database.

After a rigorous screening of titles and keywords, 435 articles were identified for the abstract screening stage. The majority of the excluded articles (18,026) were due to duplication (189), irrelevance to banking applications (6572), being theoretical studies (186), and not fitting the inclusion criteria (11,079). Following the abstract screening process, 113 articles were further excluded, leaving 322 articles, of which 10 were literature reviews and 312 were related to banking efficiency applications. Subsequently, 7 articles were excluded due to the use of different methods, resulting in a final sample of 305 articles for this study. To ensure the consistency of the data reviewing process, a coding system was created following Gough's (2007) recommendation. The weight of evidence concept was applied to make separate judgments on various review-specific criteria and combine them to form an overall judgment of the contributions of each study to answering the review question. Thus, a weight of evidence framework was established for bank technical efficiency measurement (Weight of Evidence A), a review-specific judgment of bank types (i.e., Islamic versus conventional banks) (Weight of Evidence B), and a review-specific judgment of application methods (Weight of Evidence C), as well as an overall judgment (Weight of Evidence D). To avoid overlooking significant contributions, we also screened the references cited at least five times in the selected 305 articles for their relevance to the criteria outlined in Table 1.

The PRISMA flow chart depicted in Fig. 1 demonstrates the selection process, which resulted in the inclusion of 305 articles that met all the pre-defined criteria. The subsequent analysis involved the collection of article characteristics such as the country of origin and research methodology. The empirical findings of the selected articles were then analyzed and categorized based on recurring themes. Additionally, the articles were analyzed in terms of the selection of input–output variables.

3.2 Summary statistics of reviewed articles

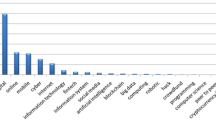

The statistical data presented in Table 2 indicates that among the selected 305 articles, 89% of the studies preferred frontier methods for their technical efficiency estimations, with 28% utilizing parametric and 61% non-parametric methods. Specifically, the non-parametric DEA method was the most frequently used (60%), followed by SFA (22%) among the parametric methods. Moreover, two-stage techniques such as Tobit (26%) and GLS (17%) were the most commonly used methods to analyze the impact of environmental variables on efficiency scores. Interestingly, the least frequently used methods were the Thick Frontier Approach (TFA) (1%), Free Disposable Hull (FDH) analysis (1%), and the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) (4%).

In terms of bank type, the analysis shows that 51% of the studies focused solely on conventional banks (CBs), while 35% of the studies analyzed the technical efficiency scores of Islamic banks (IBs) only. Furthermore, 14% of the studies compared the technical efficiency scores of IBs versus CBs. It is worth noting that the paper excluded ten literature review articles, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria of being banking application papers.

This literature review analyzed a total of 305 articles, which were published in 128 scientific journals. The majority of the articles were published in journals with a focus on business, economics, and finance. Notably, the Journal of Banking and Finance had the highest number of published articles (27), followed by the European Journal of Research (13), Managerial Finance (11), Expert Systems with Applications (8), the International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management (8), the Journal of Productivity Analysis (7), and Research in International Business and Finance (7).

4 Review of studies

4.1 Regulation as Sariah principals

Islamic banks (IBs) are subject to strict regulatory guidelines rooted in Shariah principles (Elamer 2017; Elamer et al. 2019). The unique characteristics of Islamic finance instruments can pose significant challenges for IBs in terms of efficiency and profitability. For instance, some of the specific forms of Islamic banking/finance, such as mudarabah (profit-sharing), murabaha (cost-plus), musharakah (joint-venture), bai-muajjal (deferred payment sale), ijarah (leasing), and istisna (processing and manufacturing contracts) may increase traditional agency conflicts, such as adverse selection and moral hazard problems, and worsen non-traditional agency problems by providing more opportunities for managerial expropriation of bank assets (Elamer 2017; Elamer et al. 2019).

However, some researchers have argued that these strict guidelines are also among the key factors that have enabled IBs to withstand the 2007/08 financial crisis better than most conventional banks (CBs) (Willison 2009; Yilmaz 2009; Hasan and Dridi 2010). These studies have also demonstrated that IBs have exhibited relatively high levels of efficiency and profitability during periods of financial uncertainty. Therefore, identifying the factors that account for the relatively higher performance metrics observed for IBs represents an important research agenda.

The extant literature indicates that the differences in the banking practices between Islamic and conventional banks account for the divergent efficiency and stability levels observed between the two types of banks. Islamic banking operates under the guidance of Shariah principles that prohibit the charging of interest (Hassan and Bashir 2003a, b, c). Instead, IBs generate earnings through transactional and intermediation contracts (El-Hawary et al. 2004). The main source of difference between Islamic and conventional banks is their approach to the use of money (Al-Omar and Abdel-Haq 1996). In this regard, IBs are prohibited from charging interest and, therefore, offer alternative financial products and services that conform to the principles of Shariah law, which allows for profit and loss sharing (PLS) through instruments like Musharaka and Mudarabah.

Chong and Liu (2009) defined the PLS model as a system in which profits and losses are shared among banks, depositors, and borrowers. Murabaha, which is commonly used for financing real estate, consumer durables, and the acquisition of raw materials, equipment, or machinery, is the most popular method of Islamic financing (Ahmad and Haron 2002). Empirical research by Beck et al. (2013), Metwally (1997), and Olson and Zoubi (2008) has shown that the activities of IBs differ from those of CBs. However, Aggarwal and Yousef (2000), Chong and Liu (2009), Khan (2010), Ariff and Rously (2011), and Suzuki et al. (2020) have argued that there is no fundamental difference between the banking activities of IBs and CBs.

4.2 Stability

Bank efficiency measurement has been a topic of interest in academic research and policymaking for a considerable period, with a noticeable increase in attention following the global financial crisis. Therefore, investigating the relationship between banks’ efficiency and stability has become an important topic. Issavi et al. (2018) employed DEA as the analysis method and the intermediation approach to select variables to examine the relationship between efficiency and stability of eleven Iranian private and public banks between 2004 and 2016. The findings suggested an inverse relationship between banks’ efficiency and stability indexes, with bank stability significantly impacting financial stability in an economy.

The literature presents a lack of consensus on the stability of Islamic banks (IBs) compared to their conventional counterparts (CBs). Kuran (2004) indicated that the stability of IBs is not higher than CBs, while Kabir and Worthington (2017) found IBs to be less stable than CBs in their analysis of 16 developing economies between 2000 and 2012. Ghosh (2016) proposed that capital adequacy ratios and reserve requirements are the most important factors for bank stability, with Beck et al. (2013) and Khediri et al. (2015) corroborating that liquidity and capitalization ratios are better in IBs, thereby improving their stability. Abedifar et al. (2015) found this to be the case in their analysis of data from 553 banks in 24 countries, while Rahim and Zakaria (2013) confirmed this for Malaysian IBs.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2010) reports that banks that rely primarily on interbank funding and money markets suffered severe losses during the global financial crisis. In contrast, IBs, which rely heavily on depository funding, proved to be more stable than CBs. Khan (1986) found that IBs apply 100% reserve for demand deposits and are expected to be more stable. However, high reserve requirements mean IBs have less available funds for investment, leading to lower efficiency compared to CBs.

4.3 Scale efficiency

Efficiency is a key aspect of the banking industry, and Islamic banks (IBs) have been subject to numerous studies examining their efficiency. One important component of efficiency is scale efficiency, which is the ability of a bank to optimize its operations in relation to its size. Several studies have investigated the impact of scale efficiency on the overall technical efficiency of IBs.

Havid and Setiawan (2015) found a statistically significant correlation between scale inefficiency and technical inefficiency in Indonesian IBs. Yildirim (2015) demonstrated that scale inefficiency is the most important cause of technical inefficiency in IBs in Malaysia. Rahman and Rosman (2013) examined IBs in Asian and MENA countries, concluding that IBs experienced scale efficiency problems. By reviewing numerous studies in the literature, Rahman and Rosman (2013) identified Malaysia as one of the most popular countries which attracted the interest of researchers on the efficiency of IBs relative to conventional banks (CBs). Rahman and Rosman (2013) also showed that Zainal and Ismail (2012), Ada and Dalkilic (2014), Yildirim (2015), Sufian et al. (2016) and Kamarudin et al. (2017a, b), Abdul-Majid et al. (2008, 2010) preferred stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) and Alrawashedh et al. (2014) chose financial ratios in measuring efficiency. Findings from these studies are mixed. For example, Alrawashedh et al. (2014) and Kamarudin et al. (2017a, b) noted that IBs are more efficient/profitable than CBs, contrary to the conclusions by Abdul-Majid et al. (2008, 2010, 2011a, b).

Comparing the Malaysian and Turkish banking sectors, Ada and Dalkilic (2014) utilized the Malmquist Total Factor Productivity (TFP) index as well as data envelopment analysis (DEA) and proposed that TFP change decreased in Turkey during 2010–2011 compared to 2009–2010, while it increased for most banks in Malaysia. In addition, scale efficiency was higher in Turkey during 2009 but lower for Malaysian banks in 2010 and 2011. Further, Yildirim (2015) identified scale efficiency as the main source of overall technical efficiency. This is similar to a report by Zainal and Ismail (2012) that the technical efficiency and scale efficiency of domestic IBs are higher, while foreign IBs operated at higher pure technical efficiency. Berger (2007) investigated bank efficiency differences in various countries and compared the efficiency divergence among foreign and domestically owned banks. Findings indicated that foreign-owned banks have a disadvantage compared to domestic banks in developing countries.

Singh and Fida (2015) investigated the technical efficiency of Omani commercial banks by using DEA. Technical efficiency scores were decomposed into pure and scale efficiency components. Results suggested that scale efficiency has a higher impact on technical efficiency than pure technical efficiency. In addition, the largest bank of Oman is experiencing decreasing returns-to-scale. In the second stage analysis, the impact of capital adequacy, bank size, liquidity, and profitability on efficiency is examined by using the Tobit model. Liquidity and profitability are found to be significant, whilst bank size is an insignificant factor in bank efficiency.

Several studies have applied both parametric and non-parametric methods to try to identify consistency among the results. These include, among others, Cummins and Zi (1998), Bauer et al. (1998), Hassan (2005, 2006), and Nguyen et al. (2016), who concluded that average efficiency scores varied significantly among the methods. Even though efficiency scores and rankings of banks are similar among different parametric methods, studies confirmed that the findings from parametric and non-parametric methods are inconsistent and rankings of banks are diverse (Yildirim and Philippatos 2007; Maudos et al. 1999; Weill 2004, 2009). Perera et al. (2007), Hauner and Peiris (2008), and Camanho and Dyson (1999) found bank's size as the main factor on efficiency due to scale effects. Consistent with these studies, Shamsuddin and Xiang (2012) illustrated that large banks in Australia experienced higher cost and technical efficiency than small banks, whilst lower profit efficiency.

Last but not the least point on scale efficiency, Kassim et al. (2009) showed that IBs in Malaysia are more sensitive to monetary policy changes than CBs. In line with this finding, analyzing the Turkish banking sector, Ergeç and Arslan (2013) concluded that IBs are more sensitive to interest rate change than CBs. Therefore, sensitivity to interest rate changes could be suggested as another important factor that should be considered when measuring the efficiency scores of IBs (Table 3).

4.4 Variable selection

The process of selecting appropriate variables to measure banks' economies of scale, efficiency, and productivity is a complex undertaking due to the intangible nature of the products offered to customers (Olgu 2007). Within the literature, there is no consensus on how to select input and output variables, and the Production, Value-Added, and Intermediation approaches are the three primary methods utilized, as shown in Table 4.

In the Production approach, banks are defined as firms that convert labor and capital into deposits and loans. New variable selection applications have been introduced by Resti (1997), Favero and Papi (1995), Bauer et al. (1993), Berger and DeYoung (1997), and Swank (1996). The Value-Added method, on the other hand, classifies assets or liabilities as inputs or outputs depending on whether they create or destroy value (Berger and Humphrey 1992). Finally, the Intermediation approach perceives banks as firms that transfer money from depositors to borrowers.

Table 4 provides insight into the most commonly used inputs and outputs for measuring banks' economies of scale, efficiency, and productivity. The selected inputs include labor, deposits, personnel expenses, and physical capital, while off-balance-sheet items, loans, and other earning assets are commonly used as outputs. The selection of inputs, however, remains largely dependent on the investigator's preferences. Nonetheless, the literature provides evidence on the role of deposits as either inputs or outputs. Empirical tests conducted in various studies, such as Hughes and Mester (1993) and Hughes and Mester (2019), indicate that deposits typically function as inputs. Personnel expenses have also been highlighted as a crucial input variable by Chortareas et al. (2012), Drake and Hall (2003), and Lozano-Vivas et al. (2002), given their significant role in general and administration expenditures (Johnes et al. 2014). Table 5 presents a frequency distribution of input–output variable selection based on the approaches employed in the reviewed studies.

Magrianti (2011) conducted a study that compared the efficiency scores of Indonesian Islamic banks (IBs) and conventional banks (CBs) using different variable selection approaches. The results revealed that CBs had above-average efficiency scores when assets and production methodologies were employed, whereas IBs had higher efficiency scores than average when the intermediation approach was used. The study also found that the Intermediation approach was the most commonly used approach (81%), followed by the Value-Added approach (12%) and the Production approach (7%). 'Labor' was the most frequently selected input variable, while 'loans' was the most frequently chosen output variable. The review suggests that including both 'interest expense' and 'non-interest expense' as inputs, and 'interest income' and 'non-interest income' as outputs, could significantly affect efficiency scores when comparing IBs and CBs.

4.5 Incorporating environmental variables

Efficiency measurement methods were initially applied in individual country studies. However, in the last decade, cross-country studies have become more popular in order to capture the impact of country-specific characteristics, such as regulation, market structure, macroeconomic conditions, and various bank-specific factors. Studies such as Pastor et al. (1997), Fecher and Pestieau (1993), and Berg et al. (1993) employed common or country frontiers, using both Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) and the Distribution Free Approach (DFA) in their cross-country analyses. Nevertheless, they failed to account for the potential influence of environmental variables over which bank managers have no control. Applying a common frontier assumes that all decision-making units use the same technology, which could lead to misleading results (Chaffai et al. 2001). Therefore, Pastor et al. (1997) and Chaffai et al. (2001) recommend incorporating a range of environmental variables in empirical modelling of banking efficiency, including customers' ease of access to banking services, intermediation, concentration, and average capital ratios.

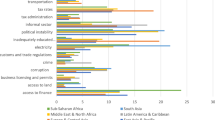

Altunbas and Chakravarty (1998), Cavallo and Rossi (2001), and Carbo et al. (2003) were among the first to conduct cross-country studies on European countries. Subsequent studies examined transition countries (Bonin et al. 2005; Kasman 2005), countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (Carvallo and Kasman 2005), developing countries (Boubakri et al. 2005; Clarke et al. 2005), and the achievements of Asian countries (Karim 2001; Williams and Nguyen 2005). More recently, researchers have compared the performance of Islamic banks (IBs) with conventional banks (CBs) in response to the increasing use of Islamic banking in many countries (Alpay and Hassan 2007; Al-Jarrah and Molyneux 2005; Yudistira 2004; Brown 2003; Hassan 2003). However, controlling for environmental variables remains a controversial issue.

The "two-stage" methodology is often used to control for environmental factors. In this method, efficiency scores measured in "stage one" using either of the frontier techniques or the financial ratios discussed in the previous sections are regressed on selected environmental factors in "stage two." Bashir (1999, 2001) used a two-stage approach to confirm the fundamental components of performance among IBs using Middle Eastern bank-level data. The results suggest that bank-specific factors such as non-interest-earning assets, customer short-term funding, and overheads influence banks' estimated efficiency scores. Bashir (1999, 2001) also recommended a negative correlation between bank deposits (measured as share reserves) and performance metrics.

A bootstrap approach is generally used in the second stage of analysis. However, Casu and Molyneux (2003) used it in the first stage to demonstrate the correlation among the covariates of the second-stage regression and error terms from the first stage. Brissimis et al. (2008) and Delis and Papanikolaou (2009) created an algorithm that relied on a double bootstrap procedure. Other models used to detect the impact of environmental variables on bank efficiency include Logit, Gaussian and Markov, and Bootstrap-Tobit, which were employed by Pastor (2002) and Casu and Girardone (2004), Wang and Huang (2007), and Casu and Molyneux (2003) and Hahn (2007) respectively. Several studies have utilized a two-stage approach to examine bank efficiency, with a focus on the Malaysian banking sector. Ismail et al. (2013), Saha et al. (2015), Defung et al. (2016), Sufian et al. (2016), and Wanke et al. (2016a, b, c) are among the most recent studies that have used this approach. With the exception of Defung et al. (2016), which employed Tobit to examine Indonesian banks, the other studies have focused on the Malaysian banking sector. The first two studies used Tobit, while Sufian et al. (2016) preferred Bootstrapping and Wanke et al. (2016a, b, c) utilized TOPSIS. According to Table 2, Tobit regression was the most commonly used two-stage technique (about 26% of the reviewed studies), followed by Generalized Least Squares (GLS), which accounted for around 17% of studies. The remaining 32% of studies employed various techniques such as Bootstrap, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), and TOPSIS.

A number of studies, including those by Sufian and Noor (2009), Ismail et al. (2013), and Saha et al. (2015), have used a two-stage Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) approach (DEA and Tobit). Sufian and Noor (2009) examined the efficiency of Islamic Banks (IBs) in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and Asian countries between 2001 and 2006. They found that loans, size, capitalization, and profitability were positively correlated with bank efficiency, while non-performing loans were negatively correlated. Saha et al. (2015) focused solely on the efficiency scores of Conventional Banks (CBs) in Malaysia between 2005 and 2012, and their findings were consistent with those of Sufian and Noor (2009). Ismail et al. (2013) analyzed both CBs and IBs in Malaysia between 2006 and 2009. They found that CBs had higher efficiency scores than IBs, and that there was a negative relationship between equity, size, and efficiency of IBs, but a positive relationship for CBs. Interestingly, a positive relationship was found to exist between expenses and efficiency in both IBs and CBs.

Azad et al. (2017) conducted a recent study that used a network DEA (NDEA), a three-stage DEA approach, to measure and compare the efficiency scores of IBs and CBs in the Malaysian banking sector between 2010 and 2015. They found that IBs performed better than CBs in terms of profitability and production, while the opposite was true in terms of intermediation. This study is important, as it highlights the limited application of NDEA in the examination of bank efficiency, which has been noted by Avkiran (2015) and Kao (2014). Kao (2014) has also argued that dynamic NDEA is rarely used in practice. Table 6 summarizes the studies that have used a two-stage analysis approach.

4.6 Islamic versus conventional bank technical efficiency

This paper reviews studies that examine the technical efficiency of Islamic banks (IBs) or conventional banks (CBs) or compare the technical efficiency of both types of banks. The studies analyzed in this paper are authored by Bader (2007), Kamarudin et al. (2017a, b), Le (2017), Aghimien et al. (2016), Islam et al. (2013), Hassan (2005), Brown and Skully (2005), Yudistria (2004), Nguyen et al. (2016), Yannick et al. (2016), Ozkan-Gunay et al. (2013), Assaf et al. (2013), Bos and Kool (2006), Weill (2004), Miah and Uddin (2017), Batir et al. (2017), Kamarudin et al. (2016a, b), Alrawashedh et al. (2014), Johnes et al. (2014), Abdul-Majid et al. (2008, 2010, 2011a,b), Al-Jarrah and Molyneux (2005), Hussein (2004), and Al-Shammari (2003).

The literature has utilized various financial ratios to evaluate bank performance, and research indicates that the relative performance of Islamic banks (IBs) and conventional banks (CBs) differs depending on the financial data analyzed. Popular financial ratios include debt-to-equity, return on investment (ROI), return on equity (ROE), and return on assets (ROA). Some studies, including Miah and Uddin (2017), Khediri et al. (2015), and Alrawashedh et al. (2014), support the assertion that IBs are more profitable, liquid, and less risky than CBs. However, others such as Milhem and Istaiteyeh (2015) demonstrate that IBs are less profitable and efficient than CBs. Sufian and Kamarudin (2016) propose that banks operating in more economically globalized nations generally have better performance metrics than their counterparts in economically protected countries.

Nienhaus (1988) discovered that Islamic banks (IBs) and conventional banks (CBs) had comparable achievements in terms of asset size, profit, and capital. Hamid (1999) proposed that IBs outperformed CBs in liquidity, profitability, productivity, and risk management. Samad and Hassan (1999) attributed this to a higher investment in government-backed securities and a higher equity-to-assets ratio. Nevertheless, the return on equity and return on assets were not significantly different for both types of banks. Iqbal (2001) compared private IBs with CBs and observed that IBs achieved greater growth in total equity, deposits, investments, total assets, and profits. However, they were less cost-efficient in terms of the total expense-to-income ratio.

In Pakistan, Moin (2008) conducted a study that found IBs and CBs had similar liquidity figures. However, the IBs in the sample were less efficient and profitable than the average for CBs, which was attributed to the IBs being younger and less experienced than CBs. Bashir (1999, 2001) corroborated these findings and identified higher costs of obtaining adequate capital ratios, loan portfolios, non-interest-earning assets, and short-term financing as crucial factors contributing to the decreasing profitability of IBs. Moreover, Hassan and Bashir (2003a, b, c) suggested that IBs' inferior asset quality compared to CBs also affects their performance.

However, Samad (2004) challenged the findings of Hassan and Bashir (2003a, b, c), stating that IBs in Bahrain are less exposed to liquidity risks due to the restrictive Shariah-compliant principles, which promote more conservative lending. Samad's study examined the performance of IBs versus CBs in Bahrain and found no significant differences in their profitability or liquidity estimates. Nevertheless, there was a significant disparity in the credit performance of both types of banks. Kader et al. (2007) observed that IBs in UAE experienced rapid growth in selected performance metrics due to the sharing of profit and loss (SPL) principle. This indicates that IBs and CBs have different characteristics in practice and should be regulated and controlled differently. The authors also suggested that IBs are generally more efficient and profitable but less liquid and less risky than CBs.

Mokhtar et al. (2006) utilized the Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) approach to investigate the overall average efficiency of IBs in Malaysia, revealing that IBs were less efficient than CBs despite significant growth in asset size, deposits, and financing compared to CBs. Furthermore, the study concluded that domestic banks were less efficient than foreign banks, regardless of organizational charter. This finding was supported by Srairi (2010), who confirmed that Western banks in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries were more cost and profit-efficient than their domestic Islamic bank counterparts.

Al-Shammari (2003) evaluated the impact of bank types and country dummy variables such as the quality of loans and capital to directly influence inefficiency. The study concluded that IBs and CBs in GCC countries were significantly less efficient than IBs. Alpay and Hassan (2007) found that, on average, IBs in Turkey were more efficient than CBs, despite having limited Shariah-compliant investment opportunities. However, unlike CBs, the productivity and technical efficiency of IBs reduced over time. In line with Alpay and Hassan (2007), Omar et al. (2007) suggested that IBs in Indonesia operate at higher profit efficiency scores compared to Western banks in the country.

Ariff and Can (2008) found that Islamic banks (IBs) and Western banks operate at similar efficiency scores, except for the age of the bank, where older Western banks are less cost-efficient compared to their Islamic bank peers. They also found that older banks are more efficient than newer banks due to their larger asset size and more experience.

In Malaysia, Kamarudin et al. (2008) discovered that the overall cost efficiency of Islamic financial institutions is lower than that of conventional banks (CBs). However, Magrianti (2011) and Rosyadi and Fauzan (2011) both reported that, in Indonesia, IBs are more efficient than CBs when the Intermediation approach is employed.

Studies on the impact of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) on bank efficiency have yielded mixed results. While Al-Khasawneh (2013) found that bank mergers have a positive correlation with efficiency gains, Montgomery et al. (2014) disagreed. Le (2016) reported no efficiency gains from M&A for both IBs and CBs in Vietnam, and Le (2017) found that efficiency scores improved in most acquired banks but showed no clear pattern in acquiring banks.

Different studies have shown contrasting results on the efficiency of IBs compared to CBs. Abdul-Majid et al. (2008, 2010, 2011a, b), Havid and Setiawan (2015), Johnes et al. (2009, 2014), Kamarudin et al. (2016a, b), Milhem and Istaiteyeh (2015), Mokhtar et al. (2007, 2008), and Srairi (2010) suggested that IBs are less efficient than CBs. In contrast, Al-Muharrami (2008), Alrawashedh et al. (2014), Batir et al. (2017), Khediri et al. (2015), Er and Uysal (2012), and Zuhroh et al. (2015) found that IBs are more efficient/profitable than CBs.

In GCC countries, Aghimien et al. (2016), Kamarudin et al. (2016a, b), Saeed and Izzeldin (2016), and Miah and Uddin (2017) compared the efficiency scores of IBs and CBs. Aghimien et al. (2016) proposed that banks in GCC countries operated at optimal scale, indicating constant or decreasing returns to scale in large banks and constant or increasing returns to scale in smaller banks. Kamarudin et al. (2016a, b) found that IBs are less efficient than CBs, consistent with the findings of Srairi (2010). Saeed and Izzeldin (2016) discovered that CBs from GCC countries had lower efficiency scores but a decrease in default risk.

Dijkstra's (2017) dissertation examines the relationship between bank economies of scale and scope and various factors such as government intervention, corporate strategy, and market power. The empirical findings reveal a positive relationship between economies of scale and mixed relationship with economies of scope.

5 Research gaps and suggestions for future research

Based on the findings of this paper, several future research paths could be identified, and recommendations can be offered. First, IBs can increase their technical efficiency scores by using their stronger stability advantage which may require regulatory flexibility in terms of asset requirements. Even though it can be suggested as an important topic both for IBs and CBs, studies reviewed in this paper focused mostly on efficiency measurement leaving stability and liquidity issues deeply unexplored. Our study broadens the technical efficiency research spectrum by suggesting diverse methodologies, contexts, and variables, including the less explored influence of interest rate changes and nuanced regulatory practices on Islamic Banks (IBs). While IBs do not directly interact with interest, economy-wide interest rate variations indirectly affect their efficiency by modifying the overall economic context. Importantly, we argue that the distinct business model of IBs, underpinned by principles such as risk-sharing and prohibition of interest, calls for a more considered regulatory approach. Rather than adopting a 'one-size-fits-all' strategy, regulators should account for the unique operational and risk profiles of IBs. Standard banking regulations like minimum capital requirements and capital conservation buffers, while universally applicable, could be fine-tuned to address the specific risks inherent to IBs, such as those amplified by extraordinary events like a pandemic. Thus, a regulatory framework considering aspects like capital adequacy, liquidity risk management, and customer protection should be informed by the distinct characteristics of Islamic banking.

Secondly, due to their structural differences and investment limitations by the Shariah principles, we recommend that IBs should be regulated and treated differently thank CBs by the authorities. This is an important policy implication that needs to be addressed in future studies which attempt to evaluate and compare the performance metrics of IBs with their conventional counterparts. Thirdly, even though investment accounts of IBs are operating on PLS principles, losses in the asset side are absorbed by equity holders. To the best of our knowledge, this may create uncertainty about the level of transparency and disclosure, which has not been clearly researched in the existing literature.

Fourthly, comparative studies of the results obtained by using different variable selection approaches are scarce. The highest proportion of studies applied the Intermediation approach in defining input–output variables, whilst studies comparing efficiency scores of both IBs and CBs with different approaches is very limited. The consistency among the efficiency scores with various input–output variable combinations can be extended in future research. Fifthly, in terms of methodological applications, future research could be extended to cover more cross-country empirical investigations using both the TFA and the DFA as parametric frontier methods.

Other areas for further research could comprise, inter alia: (i) a comparison of the robustness of different methods used in calculating banks’ efficiency scores. Evidence from existing literature shows that the three groups of methods reviewed in this paper produced diverse efficiency scores. (ii) The inclusion of non-interest expense in the choice of input variables and non-interest income in the list of output variables could have an important impact on the estimated efficiency scores, particularly for IBs. Then, the contribution of environmental factors such as Shariah principles, country-specific characteristics and management quality should be considered concurrently when estimating bank efficiency scores. (iii) The selection of performance metrics employed should be expanded to include both the standard efficiency scores and the Malmquist Total Factor Productivity Index (TFP). Such should help policymakers to achieve a more accurate rating of banks in terms of their productivity and efficiency management. A summary of research gaps and recommendations for possible future research directions is presented in Table 7.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, we presented a comprehensive systematic literature review of 305 studies focusing on the 1989–2019 period. We collected the sample after a careful review of 18,461 articles from seven leading databases by following the PRISMA flowchart. Our aim was to critically evaluate the recent technical efficiency methods of Islamic banks (IBs) and conventional banks (CBs), highlight patterns and trends, identify significant factors on bank efficiency and offer a guide to researchers as a summary of existing studies by emphasizing opportunities for future research.

Our review identified several important findings with practical and theoretical implications. First, there is mixed evidence on which group of banks i.e. IBs or CBs are more efficient; whilst more recent papers on cross-country analysis found no difference between the two types of banks. Therefore, regulators and policymakers should consider the mixed findings when evaluating the performance of different types of banks, and more research is required to reach a more definitive conclusion on this issue. Second, several studies concluded that a two-stage procedure is a more appropriate method for estimating bank efficiency since it allows for the simultaneous inclusion of variables that capture the impact of bank-specific factors as well as regional and environmental conditions, which may be incorporated more in future studies. Thus, practitioners and academics should consider employing a two-stage procedure to capture a more comprehensive view of bank efficiency. Third, our review found that applications of parametric and non-parametric techniques produce different efficiency scores. But remarkably, studies comparing findings from different methods are very limited, indicating a potential area for further research, particularly incorporating consistency tests on findings. Therefore, researchers should consider comparing different methods to provide a more comprehensive analysis of bank efficiency. Fourth, our review found that many studies applied DEA as a non-parametric method and SFA as a parametric method. However, applications of other innovative methods such as TFA, DFA and FDH in the bank efficiency context are less frequent. Therefore, there is a need for new methodological applications, and researchers should explore innovative methods to capture a more comprehensive view of bank efficiency.

Fifth, there is no consensus in the literature on the procedure for selecting input and output variables. The Intermediation approach is the most widely applied method in which ‘labor’, ‘deposits’ and ‘capital’ are the most widely chosen input variables, whilst ‘loans’ and ‘other earning assets’ are the most frequently used output variables. Other approaches such as Value-Added and Production can be employed at the same time for a comparative analysis. Thus, practitioners and academics should consider multiple approaches to selecting input and output variables to provide a more comprehensive analysis of bank efficiency.

While this review contributes to the literature on bank efficiency by providing a comprehensive analysis of technical efficiency methods used in Islamic and conventional banks, there are some limitations to our study. First, the sample size may not be fully representative of all studies on technical efficiency in Islamic and conventional banks, as we focused on papers published in seven databases only. Second, our review only covers studies published between 1989 and 2019, and it is possible that there have been developments in technical efficiency methods since then, especially after COVID-19 era. It is worth noting that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the banking industry and may have affected the efficiency of banks in various ways. Future research in this area may investigate the effects of the pandemic on bank efficiency and performance. Third, our review focused on technical efficiency and did not consider other forms of efficiency such as scale efficiency and cost efficiency. Fourth, we did not consider the impact of external factors such as macroeconomic conditions, regulatory frameworks, and political stability on bank efficiency, which could be explored in future studies. Finally, while we identified several important research gaps and opportunities, the suggestions for future research are not exhaustive and should be considered as indicative rather than definitive.

In conclusion, this review provides a summary of the recent technical efficiency methods of IBs and CBs, highlights patterns and trends, identifies significant factors on bank efficiency and offers a guide to researchers as a summary of existing studies by emphasizing opportunities for future research. The practical and theoretical implications of this review can help practitioners, academics, and policymakers better evaluate the performance of different types of banks, and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of bank efficiency.

Change history

23 March 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-024-00758-w

Notes

The covid-19 pandemic represents a significant and unprecedented disruption to the global economy, and it is likely that the pandemic has had a significant impact on banking efficiency that has yet to be fully understood or quantified. Given the scope and magnitude of the pandemic's impact, it may be more appropriate to undertake a separate study that specifically focuses on the impact of the pandemic on banking efficiency. Additionally, by limiting the scope of the current study to the pre-pandemic period, it allows for a more focused and in-depth analysis of the technical efficiency patterns.

References

Abdul-Majid M, Saal DS, Battisti G (2010) Efficiency in Islamic and conventional banking: an international comparison. J Prod Anal 34(1):25–43

Abdul-Majid M, Saal DS, Battisti G (2011a) Efficiency and total factor productivity change of Malaysian commercial banks. Serv Ind J 31(13):2117–2143

Abdul-Majid M, Saal DS, Battisti G (2011b) The impact of Islamic banking on the cost efficiency and productivity change of Malaysian commercial banks. Appl Econ 43(16):2033–3054

Abdul-Majid M, Saal DS, Battisti G (2008) The efficiency and productivity of Malaysian banks: an output distance function approach. Aston Business School Research Paper R, P0815

Abedifar P, Ebrahim S, Molyneux P, Tarazi A (2015) Islamic banking and finance: recent empirical literature and directions for future research. J Econ Surv 29(4):637–670

Abreu E, Kimura H, Sobreiro V (2019) What is going on with studies on banking efficiency? Res Int Bus Financ 47:195–219

Ada AA, Dalkilic N (2014) Efficiency analysis in Islamic banks: a study for Malaysia and Turkey. BDDK J Bank Financ Mark 8(1):9–33

Aggarwal RK, Yousef T (2000) Islamic banks and investment financing. J Money Credit Bank 32:93–120

Aghimien PA, Kamarudin F, Hamid F, Noordin B (2016) Efficiency of Gulf Cooperation Council Banks. Rev Int Bus Strateg 26(1):118–136

Ahmad N, Haron S (2002) Perceptions of Malaysian corporate customers towards Islamic banking products & services. Int J Islam Financ Serv 3(4):1–16

Alam N (2013) Impact of banking regulation on risk and efficiency in Islamic banking. J Financ Rep Account 11(1):29–50

Aliyu S, Hassan MK, Mohd Yusof R, Naiimi N (2017) Islamic banking sustainability: a review of literature and directions for future research. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 53(2):440–470

Al-Jarrah I (2007) The use of DEA in measuring efficiency in Arabian banking. Banks Bank Syst J 2(4):21–30

Al-Jarrah I, Molyneux P (2005) Efficiency in Arabian banking, Islamic perspectives on wealth creation. Edinburgh University, Edinburgh, pp 97–117

Al-Khasawneh JA (2013) Pairwise X-efficiency combinations of merging banks: analysis of the fifth merger wave. Rev Quant Financ Acc 41(1):1–28

Almaqtari F, Al-Homaidi E, Tabash M, Farhan N (2018) The determinants of profitability of Indian commercial banks: a panel data approach. Int J Financ Econ 24(1):168–185

Al-Muharrami S (2007) The causes of productivity change in GCC banking industry. Int J Product Perform Manag 56(8):731–743

Al-Muharrami S (2008) An examination of technical, pure technical and scale efficiencies in GCC banking. Am J Finance Account 1(2):152–166

Al-Omar F, Abdel-Haq (1996) Islamic banking: theory, practice and challenges. Oxford University Press, Karachi

Alpay S, Hassan MK (2007) A comparative efficiency analysis of interest free financial institutions and conventional banks: a case study on Turkey. Economic research forum, working paper series, 0714

Alrawashedh M, Sabri SRM, Ismail MT (2014) The significant financial ratios of the Islamic and conventional banks in Malaysia region. Res J Appl Sci Eng Technol 7(14):2838–2845

Al-Shammari SH (2003) Structure-conduct-performance and efficiency in Gulf Cooperation Council. Ph.D. thesis, University of Wales, Bangor

Altunbas Y, Chakravarty SP (1998) Efficiency measures and the banking structure in Europe. Econ Lett 60(2):205–208

Ariff M, Can L (2008) Cost and profit efficiency of Chinese banks: a nonparametric analysis. China Econ Rev 19(2):260–273

Ariff M, Rosly SA (2011) Islamic banking in Malaysia: unchartered waters. Asian Econ Policy Rev 6(2):301–319

Assaf AG, Matousek R, Tsionas EG (2013) Turkish bank efficiency: Bayesian estimation with undesirable outputs. J Bank Finance 37(2):506–517

Ataullah A, Le H (2006) Economic reforms and bank efficiency in developing countries: the case of the Indian banking industry. Appl Financ Econ 16(9):653–663

Athanassopoulos AD (1997) Service quality and operating efficiency synergies for management control in the provision of financial services: evidence from Greek bank branches. Eur J Oper Res 98(2):300–313

Athanassopoulos AD, Curram SP (1996) A comparison of data envelopment analysis and artificial neural networks as tools for assessing the efficiency of decision making units. J Oper Res Soc 47(8):1000–1016

Avkiran NK (2009) Opening the black box of efficiency analysis: an illustration with UAE banks. Omega 37(4):930–941

Avkiran NK (2015) An illustration of dynamic network DEA in commercial banking including robustness tests. Omega 55:141–150

Ayadi F, Adebayo A, Omolehinwa E (1998) Bank performance measurement in a developing economy: an application of data envelopment analysis. Manag Financ 24:5–16

Aysan AF, Ceyhan SP (2008) What determines the banking sector performance in globalised financial market? The case of Turkey. Phys A Stat Mech Its Appl 387(7):1593–1602

Azad A, Kian-Teng K, Talib M (2017) Unveiling black-box of bank efficiency. Int J Islam Middle East Finance Manag 10(2):149–169

Bader MK (2007) Cost, revenue and profit efficiency of conventional banks: evidence from nineteen developing countries. In: Ariff M, Shamsher M, Hassan T (eds) Capital markets in emerging markets: Malaysia (chapter 25). McGraw-Hill, Kuala Lumpur

Barros C, Chen Z, Liang Q, Peypoch N (2011) Technical efficiency in the Chinese banking sector. Econ Model 28(5):2083–2089

Barros CP, Managi S, Matousek R (2012) The technical efficiency of the Japanese banks: non-radial directional performance measurement with undesirable output. Omega 40(1):1–8

Bashir AM (1999) Risk and profitability measures in Islamic banks: the case of two Sudanese banks. Islam Econ Stud 6(2):1–24

Bashir A (2001) Assessing the performance of Islamic banks: some evidence from the Middle East, topics in Middle Eastern and North African economies, unpublished paper. In: Proceedings of the Middle East Economic Association

Batir TE, Volkman DA, Gungor B (2017) Determinants of bank efficiency in Turkey: participation banks versus conventional banks. Borsa Istanbul Rev 17(2):86–96

Battacharya A, Lovell CAK, Sahay P (1997) The impact of liberalisation on the productive efficiency of Indian commercial banks. Eur J Oper Res 98:332–345

Bauer PW, Berger AN, Humphrey DB (1993) Efficiency and productivity growth in US banking. Meas Prod Effic Tech Appl 1:386–413

Bauer PW, Berger AN, Ferrier GD, Humphrey DB (1998) Consistency conditions for regulatory analysis of financial institutions: a comparison of frontier efficiency methods. J Econ Bus 50:85–114

Beccalli E, Casu B, Girardone C (2006) Efficiency and stock performance in European banking. J Bus Financ Account 33(1–2):245–262

Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Merrouche O (2013) Islamic vs. conventional banking: business model, efficiency and stability. J Bank Finance 37(2):433–447

Belanès A, Ftiti Z, Regaïeg R (2015) What can we learn about Islamic banks efficiency under the subprime crisis? Evidence from GCC Region. Pac Basin Finance J 33:81–92

Bele S, Zerihun B, Tilahun G (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on the financial performance of banks: evidence from Ethiopia. J Econ Bus 113:105996

Berg S, Forsund F, Jansen E (1992) Malmquist indices of productivity growth during the deregulation of Norwegian banking, 1980–89. Scand J Econ 94(Supplement):211–228

Berg SA, Førsund FR, Hjalmarsson L, Suominen M (1993) Banking efficiency in the Nordic countries. J Bank Finance 17(2–3):371–388

Berger AN (2007) International comparisons of banking efficiency. Financ Mark Inst Instrum 16(3):119–144

Berger AN, DeYoung R (1997) Problem loans and cost efficiency in commercial banks. J Bank Finance 21(6):849–870

Berger AN, Humphrey DB (1992) Measurement and efficiency issues in commercial banking. In: Output measurement in the service sectors. University of Chicago Press, pp 245–300

Bhatia V, Basu S, Mitra SK, Dash P (2018) A review of bank efficiency and productivity. Opsearch 55:557–600

Bonin JP, Hasan I, Wachtel P (2005) Bank performance, efficiency and ownership in transition countries. J Bank Finance 29(1):31–53

Bos JWB, Kool CJM (2006) Bank efficiency: the role of bank strategy and local market conditions. J Bank Finance 30:1953–1974

Bos J, Koetter M, Kolari J, Kool C (2009) Effects of heterogeneity on bank efficiency scores. Eur J Oper Res 195:251–261

Boubaker S, Le TDQ, Ngo T (2022) Managing bank performance under COVID-19: a novel inverse DEA efficiency approach. Int Trans Oper Res 30(5):2436–2452

Boubaker S, Uddin MH, Kabir SH, Mollah S (2023) Does cost inefficiency in Islamic banking matter for earnings uncertainty? Rev Acc Financ 22(1):1–36

Boubakri N, Cosset JC, Fischer K, Guedhami O (2005) Privatization and bank performance in developing countries. J Bank Finance 29(8–9):2015–2041

Brissimis SN, Delis MD, Papanikolaou NI (2008) Exploring the nexus between banking sector reform and performance: evidence from newly acceded EU countries. J Bank Finance 32(12):2674–2683

Brockett PL, Charnes A, Cooper WW, Huang ZM, Sun DB (1997) Data transformations in DEA cone ratio envelopment approaches for monitoring bank performances. Eur J Oper Res 98(2):250–268

Brown K (2003) Islamic banking comparative analysis. Arab Bank Rev 5(2):43–50

Brown K, Skully M (2005) Islamic banks: a cross-country study of cost efficiency performance, accounting, commerce and finance. Islam Perspect J 8(1–2):43–79

Camanho AS, Dyson RG (1999) Efficiency, size, benchmarks and targets for bank branches: an application of data envelopment analysis. J Oper Res Soc 50:903–915

Canhoto A, Dermine J (2003) A note on banking efficiency in Portugal, new vs. old banks. J Bank Finance 27(11):2087–2098

Carbo V, Humphrey SD, Rodríguez F (2003) Deregulation, bank competition and regional growth. Reg Stud 37:227–237

Carvallo O, Kasman A (2005) Cost efficiency in the Latin American and Caribbean banking systems. Int Financ Mark Inst Money 15:55–72

Carvallo O, Kasman A (2017) Convergence in bank performance: evidence from Latin American banking. N Am J Econ Finance 39:127–142

Casu B, Girardone C (2009) Does competition lead to efficiency? The case of EU commercial banks. Cass Business School, working paper series, WP 01/09

Casu B, Molyneux P (2003) Comparative study of efficiency in European banking, Wharton school research paper, no 17

Casu B, Girardone C (2002) A comparative study of the cost efficiency of Italian bank conglomerates. Manag Finance 28(9):3–23

Casu B, Girardone C (2004) Financial conglomeration: efficiency, productivity and strategic drive. Appl Financ Econ 14:687–696

Cavallo L, Rossi SPS (2001) Scale and scope economies in the European banking systems. J Multinatl Financ Manag 11(4–5):515–531

Chaffai ME, Dietsch M, Lozano-Vivas A (2001) Technological and environmental differences in the European banking industries. J Financ Res 19(2–3):147–162

Chan S, Koh E, Zainir F, Yong C (2015) Market structure, institutional framework and bank efficiency in ASEAN 5. J Econ Bus 82:84–112

Chang TC, Chiu YH (2006) Affecting factors on risk-adjusted efficiency in Taiwan’s banking industry. Contemp Econ Policy 24(4):634–648

Chen T, Yeh T (2000) A measurement of bank efficiency, ownership and productivity changes in Taiwan. Serv Ind J 20(1):95–109

Chen X, Skully M, Brown K (2005) Banking efficiency in China: application of DEA to pre-and post-deregulation eras: 1993–2000. China Econ Rev 16(3):229–245

Chen Z, Matousek R, Wanke P (2018) Chinese bank efficiency during the global financial crisis: a combined approach using satisficing DEA and support vector machines☆. N Am J Econ Finance 43:71–86

Chen X, You X, Chang V (2021) FinTech and commercial banks’ performance in China: a leap forward or survival of the fittest? Technol Forecast Soc Change 166:120645

Cherchye L, Kuosmanen T, Post T (2001) FDH directional distance functions with an application to European commercial banks. J Prod Anal 15:201–215

Chong BS, Liu MH (2009) Islamic banking: interest-free or interest-based? Pac Basin Finance J 17(1):125–144

Chortareas GE, Girardone C, Ventouri A (2012) Bank supervision, regulation and efficiency: evidence from the European Union. J Financ Stab 8:292–302

Clarke G, Cull R, Shirley MM (2005) Bank privatization in developing countries: a summary of lessons and findings. J Bank Finance 29(8–9):1905–1930

Cummins JD, Zi H (1998) Comparison of frontiers efficiency methods: an application to the US life insurance industry. J Prod Anal 10:131–152

Dar H (2003) Handbook of international banking. Edward Elgar (Chap. 8)

Defung F, Salim R, Bloch H (2016) Has regulatory reform had any impact on bank efficiency in Indonesia?: A two-stage analysis. Appl Econ 48(52):5060–5074

Degl’Innocenti M, Matousek R, Sevic Z, Tzeremes NG (2017) Bank efficiency and financial centres: Does geographical location matter? J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 46:188–198

Delis MD, Papanikolaou NI (2009) Determinants of bank efficiency: evidence from a semi-parametric methodology. Manag Finance 35(3):260–275

DeYoung R (1997) A diagnostic test for the distribution-free efficiency estimator: an example using U.S. commercial bank data. Eur J Oper Res 98(2):243–249

Dietsch M, Lozano-Vivas A (2000) How the environment determines banking efficiency: a comparison between French and Spanish industries. J Bank Finance 24(6):985–1004

Dijkstra M (2017) Economies of scale and scope in banking: Effects of government intervention, corporate strategy and market power. Amsterdam University Press

Dogan E, Fausten D (2003) Productivity and technical change in Malaysian banking: 1989–1998. Asia-Pac Finan Mark 10:205–237

Drake L, Hall MJ (2003) Efficiency in Japanese banking: an empirical analysis. J Bank Finance 27(5):891–917

Drake L, Hall MJB, Simper R (2006) The impact of macroeconomic and regulatory factors on bank efficiency: a non-parametric analysis of Hong Kong’s banking system. J Bank Finance 30:1443–1466

Drake L, Hall MJB, Simper R (2009) Bank modelling methodologies: a comparative non-parametric analysis of efficiency in the Japanese banking sector. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 19:1–15

Du K, Sim N (2016) Mergers, acquisitions, and bank efficiency: cross-country evidence from emerging markets. Res Int Bus Financ 36:499–510

Elamer AA, Ntim CG, Abdou HA, Zalata AM, Elmagrhi M (2019) The impact of multi-layer governance on bank risk disclosure in emerging markets: the case of Middle East and North Africa. In: Accounting forum, vol 43(2). Routledge, pp 246–281

Elamer AA (2017) Empirical essays on risk disclosures, multi-level governance, credit ratings, and bank value: evidence from MENA banks. Doctoral dissertation, University of Huddersfield

El-Gamal MA, Inanoglu H (2005) Inefficiency and heterogeneity in Turkish banking: 1990–2000. J Appl Economet 20(5):641–665

El-Hawary D, Grais W (2004) Regulating Islamic financial institutions: the nature of the regulated, 3227. World Bank Publications

Emrouznejad A, Anouze AL (2010) DEA/C&R: DEA with classification and regression tree: a case of banking efficiency. Expert Syst (in press)

English M, Grosskopf S, Hayes K, Yaisawarng S (1993) Output allocative and technical efficiency of banks. J Bank Finance 17:349–366

Er B, Uysal M (2012) Turkiyedeki geleneksel bankalar ve islami bankalarin karsilastirmali etkinlik analizi: 2005–2010 donemi degerlendirmesi. Ataturk Universitesi Iktisadi Ve Idari Bilimler Dergisi 26(3–4):365–387

Ergeç EH, Arslan BG (2013) Impact of interest rates on Islamic and conventional banks: the case of Turkey. Appl Econ 45(17):2381–2388

Favero CA, Papi L (1995) Technical efficiency and scale efficiency in the Italian banking sector: a non-parametric approach. Appl Econ 27(4):385–395

Fecher F, Pestieau P (1993) Efficiency and competition in OECD financial services. In: Fried HO, Schmidt SS (eds) The measurement of productive efficiency: techniques and applications. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 374–385

Fukuyama H (1993) Technical and scale efficiency of Japanese commercial banks: a non-parametric approach. Appl Econ 25(8):1101–1112

Fukuyama H (1996) Returns to scale and efficiency of credit associations in Japan: a nonparametric frontier approach. Jpn World Econ 8(3):259–277

Fukuyama H, Matousek R (2011) Efficiency of Turkish banking: two-stage network system. Variable returns to scale model. Int Financ Mark Inst Money 21:75–91

Fukuyama H, Weber WL (2009) A directional slacks-based measure of technical inefficiency. Socioecon Plan Sci 43(4):274–287

Fung MK (2006) Scale economies, X-efficiency, and convergence of productivity among bank holding companies. J Bank Finance 30:2857–2874

Gardener E, Molyneux P, Nguyen-Linh H (2011) Determinants of efficiency in South East Asian banking. Serv Ind J 31:2693–2719

Ghosh S, McGuckin JT, Kumbhakar SC (1994) Technical efficiency, risk attitude, and adoption of new technology: the case of the US dairy industry. Technol Forecast Soc Change 46(3):269–278

Ghosh AR, Ostry JD, Chamon M (2016) Two targets, two instruments: Monetary and exchange rate policies in emerging market economies. J Int Money Finance 60:172–196

Giokas D (1991) Bank branches operating efficiency: a comparative application of DEA and loglinear model. Omega 19:549–557

Golany B, Storbeck J (1999) A data envelopment analysis of the operational efficiency of bank branches. Interfaces 29:14–26

Gough D (2007) Weight of evidence: a framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Res Pap Educ 22(2):213–228

Hahn FR (2007) Domestic mergers in the Austrian banking sector: a performance. Appl Financ Econ 17:185–196

Hall MJ, Kenjegalieva KA, Simper R (2012) Environmental factors affecting Hong Kong banking: a post-Asian financial crisis efficiency analysis. Glob Financ J 23:184–201

Halme M, Korhonen P, Eskelinen J (2014) Non-convex value efficiency analysis and its application to bank branch sales evaluation. Omega 48:10–18

Hamid MA (1999) Islamic banking in Bangladesh: expectations and realities. In: International conference on Islamic economics in the 21st Century: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Hasan M, Dridi J (2010) The effects of the global crisis on Islamic and conventional banks: a comparative study. IMF working paper, WP/10/201

Hassan MK (2006) The X-efficiency in Islamic banks. Islam Econ Stud 13(2):49–77

Hassan M, Aliyu S (2018a) A contemporary survey of Islamic banking literature. J Financ Stab 34:12–43

Hassan MK, Hussein KA (2003) Static and dynamic efficiency in the Sudanese banking system. Rev Islam Econ 14:5–48

Hassan MK, Bashir AM (2003a) Determinants of Islamic banking profitability, ERF paper

Hassan MK, Bashir AHM (2003b) Determinants of Islamic banking profitability. In: Paper presented at the 10th ERF annual conference, 16–18 December, Morocco

Hassan MK, Bashir AHM (2003c) Determinants of Islamic banking profitability. In: 10th ERF annual conference, Morocco, vol 7, pp 2–31

Hassan MK (2003) Cost, profit and X-efficiency of Islamic banks in Pakistan, Iran and Sudan. In: International seminar on Islamic banking: risk management, regulation and supervision, September 30–October 2, Jakarta, Indonesia

Hassan K (2005) The cost, profit and X-efficiency of Islamic banks. In: Presented at ERF's (economic research forum) 12th annual conference, Cairo, Egypt

Hauner D (2005) Explaining efficiency differences among large German and Austrian bank. Appl Econ 37(9):969–980

Hauner D, Peiris SJ (2008) Banking efficiency and competition in low income countries: the case of Uganda. Appl Econ 40(21):2703–2720

Havid SAH, Setiawan C (2015) Bank efficiency and non-performing financing (NPF) in the Indonesian Islamic banks. Asian J Econ Model 3(3):61–79

Henriques I, Sobreiro V, Kimura H, Mariano E (2018) Efficiency in the Brazilian banking system using data envelopment analysis. Future Bus J 4(2):157–178

Holod D, Lewis HF (2011) Resolving the deposit dilemma: a new DEA bank efficiency model. J Bank Finance 35:2801–2810

Huang T, Lin C, Chen K (2017) Evaluating efficiencies of Chinese commercial banks in the context of stochastic multistage technologies. Pac Basin Financ J 41:93–110

Hughes JP, Mester LJ (2019) Modeling, evidence, and some policy implications. In: The Oxford handbook of banking, p 229

Hughes JP, Mester LJ (1993) A quality and risk-adjusted cost function for banks: evidence on the “too-big-to-fail” doctrine. J Prod Anal 4(3):293–315

Hussein KH (2004) Banking efficiency in Bahrain: Islamic versus conventional banks. Islamic Development Bank, Islamic Research and Training Institute, research paper, 68

Iqbal M (2001) Islamic and conventional banking in the nineties: a comparative study. Islam Econ Stud 8:1–27

Iqbal M, Molyneux P (2005) Efficiency in Islamic banking. In: Thirty years of Islamic banking. Palgrave Macmillan studies in banking and financial institutions. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Isik I (2007) Bank ownership and productivity developments: evidence from Turkey. Stud Econ Financ 24:115–139

Isik I, Hassan K (2002a) Technical, scale and allocative efficiencies of Turkish banking industry. J Bank Finance 26(4):719–766

Isik I, Hassan MK (2003) Efficiency, ownership and market structure, corporate control and governance in the Turkish banking industry. J Bus Financ Acc 30:1363–1421

Islam J, Rahman MA, Hasan MH (2013) Efficiency of Islamic banks a comparative study on South-East Asia and South Asian region. In: Proceedings of the 9th Asian business research conference, held on 20–21 December, 2013 at BIAM Foundation, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Islamic Financial Services Industry Stability Report (2019) Islamic Financial Services Board, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. https://www.ifsb.org/download.php?id=5231&lang=English&pg=/index.php

Ismail F, Abd. Majid MS, Ab. Rahim R (2013) Efficiency of Islamic and conventional banks in Malaysia. J Financ Rep Account 11(1):92–107

Issavi M, Tari F, Ansari SH, Amozad KH (2018) The relationship between the stability and technical efficiency of Iranian banks in the years (2004–2016)