The Best Bosses Are Humble Bosses—The Wall Street Journal (2018).

Abstract

Humility, defined as a multidimensional construct comprising an accurate assessment of one’s characteristics, an ability to acknowledge limitations and strengths, and a low self-focus, is a complex trait to potentially counterbalance detrimental effects of “negative” personal traits (e.g., narcissism), thereby making it relevant to researchers and practitioners in Management and Psychology. Whereas the study of the humility construct has become ubiquitous in Social Psychology, to our best knowledge, a review of the effects of humility in the contexts of company leaders (i.e., Chief Executive Officers) is lacking. Our systematic review suggests that CEO humility, directly and indirectly, affects a variety of individual, team, and organizational level constructs. Implications for research and practice are discussed, providing a future agenda for the construct to reach its full potential despite its relative novelty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

After the last financial crisis that led to massive economic, social, and institutional downswings, industrial psychologists and economists have wondered why Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) exert increased pathological and non-pathological personality dispositions such as psychopathy and narcissism (e.g., Boddy 2011).

We propose that CEO humility could be the answer to prevent not just detrimental (illegal) organizational outcomes such as fraud, but also stimulate favorable individual, team, and organizational outcomes. Although humility is seen as a meta-value across major religions and philosophers (see Grenberg 2010 for a review of Kant’s perspective on humility), studying groups of virtues such as wisdom, forgiveness, or humility represent “black holes” in Psychological Science (Tangney 2002) as well as fundamental measurement challenges in the Psychological Science (Tangney 2002). Given that humility lacks an established measure and may not be conceptionally different from related constructs, why has humility emerged in Management research and how has Management research developed from Tangney’s (2002) notion?

Humility has recently been enthusiastically embraced by Management scholars as a potential counterbalancing trait to destructive leadership traits such as narcissism (e.g., Morris et al. 2005; Owens et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2017), opening up the possibility that both traits can be possessed at the same time in a person. Paradoxically, social psychology researchers appear to be less enthusiastic about the possibilities of the construct by pointing to measurement problems of humility (McElroy-Heltzel et al. 2017).

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is fourfold. First, to contrast prior research in Social Psychology on humility with evidence in the Management literature to explain the paradoxical paths both constructs have taken in two distinct research fields. Second, to provide an overview of the literature on CEO humility by deconstructing its empirical articles, findings, employed methods, and main variables in top-tier Management outlets. Third, to derive, based on these results, a thematic list and an integrative framework that enables researchers and practitioners in the field to gain insights about the antecedents and consequences of CEO humility. Fourth, based on these results, to analyze several content and methodological results that may shape a future research agenda, thereby utilizing divergent approaches from foundational Social Psychology research until contemporary Management research.

However, while first Management studies have uncovered relationships of humility on firm outcomes (e.g., Ou et al. 2016), to our best knowledge, there is no systematic review gathering the empirical evidence on CEO humility and its effects on the individual, team or organizational outcomes. This is even more surprising given the voluminous theoretical (e.g., Richards 1992), empirical (e.g., Barends et al. 2019) as well structured review articles (Davis et al. 2010; Wright et al. 2016) of humility in Social Psychology. Taken together, these Social Psychological studies “show a close association between humility and numerous positive attributes and character strengths, suggesting that humility is a powerfully pro-social virtue with psychological, moral, and social benefits” (Wright et al. 2016, p. 8). However, commonly used cohorts such as students can be problematic when generalizing to other cohorts (e.g., Hanel and Vione 2016) such as top executives, thereby emphasizing the need to contrast different research strands via a review.

Management research has been criticized for drawing on multiple theoretical perspectives without a dominant theoretical or methodological paradigm, borrowing from fields such as Economics or Psychology (Nag et al. 2007). However, shared visions, norms, and practices such as a focus on the CEO as a main level of analysis explain its paradoxical success, with a constant need to integrate divergent research traditions because “an academic field is a socially constructed entity” (Nag et al. 2007, p. 935). Therefore, reviews can help bridge the divide between research paradigms (Durand et al. 2017), enabling to review of the accumulation of empirical evidence on CEO humility in the literature distinct from Social Psychological research. We do so by using a structured literature review in top-tier academic Management journals. Our review indicates that humility is a complex construct but that there is surprisingly robust evidence regarding the positive effects of leader humility. Our review also indicates that there are still major conceptual and empirical challenges in the literature that may impede our understanding of leader humility. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

The remainder of the manuscript is structured as follows. We first define the construct, elaborate on the importance of humility, and derive the dimensions of the construct. We then elaborate on our data and selection criteria employed for the review as well as the coding. We then provide an overview of the results and discuss them. We subsequently divide the discussion on differentiating humility from related constructs, in methodological developments and a discussion on demographic, structural and industry variables and content trends. These broad characteristics and descriptive developments form finally a basis to derive implications and recommendations for theory and practice.

2 Defining humility

Humility derives its meaning from the Latin word humilis, meaning “low,” “grounded,” “humble,” “from the earth,” or “insignificant.” The Oxford Dictionary defines humility as “the quality of not being proud because you are aware of your bad qualities.” Furthermore, it defines humility as “the feeling or attitude that you have no special importance that makes you better than others; a lack of pride” (Oxford Dictionary). The virtue is seen in monotheistic traditions of Judaism, Islam, and Christianity as submission before and to God to counter position humility to selfish behavior and vanity (Morris et al. 2005). Therefore, religious origins propagate humility as a counter behavior to the German term “Hochmut” (arrogance, haughtiness, and extreme pride). Nietzsche and, in particular, Kant considered true humility to be the awareness of the insignificance of one’s moral worth in comparison with the law, whereby Kant believed in the shift from a comparative-competitive fashion towards the equality of persons as a guiding value in the choice of actions (Grenberg 2010). For Kant, the virtue of humility means an agent's proper perspective on herself as a dependent and corrupt but capable and dignified rational agent. Thereby, Kant implicitly distinguishes between having a low opinion of oneself and considering oneself to be as valuable as another (Grenberg 2010; Morris et al. 2005). Similarly, Richards (1992) argues that humility is the ability not to exaggerate your self-worth. Consequently, it is a distinct construct to seemingly related constructs such as modesty because it only overlaps with the dimension of an accurate self-view (Davis et al. 2010; Garcea et al. 2012). Worthington (2017) argues that humble individuals may be selectively aware of one’s excellence, but they do not pay special attention to this status. Tangney (2000) argues that humility is also distinct from the low self-regard hypothesis because the ability to keep one’s talents and deficits in perspective and acknowledge them requires a great deal of self-esteem. Following (Tangney 2000, 2002), humility is a positive trait that is both stable and enduring (dispositional), thereby a component of one´s personality. It can also be a state characterized by feelings of humility in some moments but not in others (Tangney 2002). Similarly, Roberts and Wood (2003) coin the term “intellectual humility” in the epistemic domain, whereby humble individuals embrace partners in cognitive activity but show low concern for status due to great concern for epistemic goods. Therefore, the authors also state that this makes intellectual humility a state and relational quality as it relies not on a single person's belief. Moreover, by discussing various expert definitions (psychologists, philosophers), Tangney (2000, p. 73) summarizes the complex construct as follows:

-

Accurate assessment of one’s abilities and achievements (not low self-esteem, self-deprecation)

-

Ability to acknowledge one’s mistakes, imperfections, gaps in knowledge, and limitations (often vis-a-vis a “higher power”)

-

Openness to new ideas, contradictory information, and advice

-

Keeping one's abilities and accomplishments, one's place in the world in perspective (e.g., seeing oneself as just one person in the larger scheme of things)

-

Low self-focus, while recognizing that one is but one part of the larger universe

-

Appreciation of the value of all things and the many different ways that people and things can contribute to our world.

In their theoretical contribution, Morris et al. (2005) conceive humility by covering the dimensions of a) self-awareness (ability to understand one´s strengths and weaknesses), b) openness (awareness of personal limitations and imperfections), and c) transcendence (acceptance of something greater than the self); all three dimensions can be found in Tangney (2000) as well as in Morris et al. (2005), indicating a common base conceptualization of the construct. In addition, humility can be conceptualized as an intra-personal and inter-personal characteristic (Argandona 2015). Owens et al. (2013, p. 1518) position humility in the psychological trait theory and argue that expressed humility represents “an individual characteristic that emerges in social interactions is behavior-based, and is recognizable to others.” We see the key aspects of observability and individual characteristics also in relational humility as Davis et al. (2011, p. 226) define relational humility as “observer's judgment that a target person (a) is interpersonally other-oriented rather than self-focused, marked by a lack of superiority; and (b) has an accurate view of self—not too inflated or too low.”

Taken together, humble individuals do not refrain from self-comparisons per se but are aware of their own weaknesses and limitations. They believe that something is greater than the self. Ironically, the awareness of their own limitations and imperfections makes them more open-minded to work on these limitations, accept failure pragmatically, and embrace the contribution of other individuals. Although humility in the general literatureFootnote 1 has been linked with various constructs, we revert to Tangney’s (2002) baseline definition of humility that differentiates humility from three major constructs: self-esteem, narcissism, and modesty. Therefore, we pay special attention to these constructs by gathering evidence in the general literature and by searching our specific literature for observations on whether or how these constructs have been amended. In other words, we focus particularly on developments of the construct across time to determine whether it can be considered a “new” construct as well as empirical challenges in the literature across time that may impede its measurement. Having clear-cut constructs is a premise for empirical measurement and hence a premise for scientific inquiry of socially important yet hard-to-measure constructs. In addition, we use Podsakoff and Dalton’s (1987) general framework to code generally established structural elements in Organizational Science, such as the level of analysis or the type of dependent variable. Since generally established norms may vary across the field of studies such as Psychology, Economics, or Management, this is not meant to depict “better” or “worse” practices; rather, this framework is intended to provide ex-ante established dimensions of what is considered important when analyzing scholarly articles in the field.

3 The importance of humility

For at least six reasons, we believe that studying humility in organizational contexts is important and that a dedicated analysis of antecedents, measures, and outcomes in organizational contexts is beneficial to advancing our understanding of humility.

First, accounting scandals in the last 30 years, a number of unethical business practices by large companies, large compensation discrepancies between CEOs and other organizational members, as well as political scandals, have led business practice to consider humility as a positive trait in leadership (e.g., The Economist 2013; The Wall Street Journal 2018). Previous literature drawing on upper-echelon-theories tended to focus on observable traits of CEOs and Top-Management-Teams (TMTs) (e.g., Yoon et al. 2016), thereby neglecting unobservable traits such as humility. Second, humility as a practical tool or leadership trait has been dominated by theoretical or anecdotal evidence without an empirical basis (e.g., Collins 2001; Morris et al. 2005). Third, business academia has repeatedly acknowledged humility as a key trait of leaders (e.g., Argandona 2015), since humility is “corrective to our own natural tendency to strongly prioritize our own needs, interests, desires, and benefits” (Wright et al. 2016, p. 5). More than a decade ago, Vera and Rodriguez-Lopez (2004, p. 393) argued in their qualitative article that humility is not “shyness, lack of ambition, passivity, or lack of confidence” but a competitive advantage for organizations: valuable, rare, irreplaceable, and difficult to imitate. Hence, the construct was introduced into organizational spheres a long time ago. Fourth, the construct of humility has been proposed as an extension of classical personality constructs such as the five-factor model by incorporating honesty-humility as a sixth dimension (HEXACO-model of personality; Ashton and Lee 2007). Fifth, ever since Hambrick and Mason (1984) proposed that Chief Executive Officer’s (CEO) observable and unobservable characteristics affect key organizational outcomes (see Carpenter et al. 2004 for a review), research in the Economics, Marketing, Accounting and Strategic Management literature has been dominated by unobservable, “negative” CEO traits (i.e., narcissism: Buyl et al. 2017; Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007; Enke 2015; Gerstner et al. 2013; Ham et al. 2017; Olsen et al. 2014; Rijsenbilt and Commandeur 2013). Given the overreaching evidence of CEO narcissism on key organizational outcomes (e.g., the propensity of fraud; risk profile; M&A activities; firm performance variance), the construct of CEO humility has been theoretically proposed as a counterbalancing trait to mitigate the detrimental effects of “negative” traits such as narcissism or overconfidence (e.g., Morris et al. 2005). This is relevant to research and practice because “narcissists clearly lack many of the essential components of humility” (Tangney 2000, p. 75). Moreover, empirical research (Lee and Ashton 2005) shows a strong negative correlation between the Dark Triad (Psychopathy, Machiavellianism and Narcissism) and the honest-humility scale in the cohort of undergraduate students. In addition, leadership research in the general population (averaged 32.8 years in age) using an experimental approach testing responsiveness of CEOs to lawsuits (O’Reilly et al. 2017) found an honest-humility score of the HEXACO personality instrument to be highly correlated (r = − .69, p < .01) with the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI). Given the previously cited references, it is reasonable to propose the humility construct as a key mechanism to mitigate detrimental effects of the Dark Triad (in particular traits such as narcissism) on individual, team, and organizational outcomes, thereby making it highly important to researchers and practitioners in Management Science.

Sixth and perhaps most importantly, any study that attempts to differentiate between “leaders” and the “general public”—as we do—must provide evidence for this theoretical assumption. Economic evidence on manager fixed effects indicates that CEOs matter for a wide range of company decisions (e.g., Bertrand and Schoar 2003). Variance decomposition studies of CEOs with commonly used industry level, firm-level, and time level variables on commonly used organizational performance outcomes such as Return on Assets show an effect of 13% (Crossland and Hambrick 2007), 23.8% (Mackey 2008) or up to 38.5% (Hambrick and Quigley 2014). These studies show that CEOs have a significant effect on company decisions and subsequent performance under ceteris paribus conditions. Providing this evidence, we believe it is important to differentiate between general cohorts studying humility and cohorts using other cohorts. In fact, humility researchers frequently question whether commonly used individuals such as “MTurk participants might differ from other samples in ways relevant to the nature of humility” (Banker and Leary 2019, p. 14), thereby questioning the generalization of humility results in Management contexts. Because of our conservative assumption—based on empirical evidence—that CEO cohorts are considerably different from the general public, we define CEOs as bounded rational individuals with a distinct cognitive base and values that represent a visible and observable reflection of a TMT with a variety of consequences for strategic choices of companies (Hambrick and Mason 1984).

4 Data and method

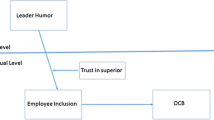

We start the search by employing search strings relevant to the focus (i.e., humility) and level of analysis (i.e., CEO) of the article in Elsevier Scopus, one of the largest peer-reviewed databases, that were published until August 2019 in the article title, abstract, and keywords. We derive the keyword search from established prior literature, conceptualizing humility as distinct from other constructs. For instance, Owens et al. (2013) argue that modesty is less focused on the motivation for learning and personal development. Therefore, it is more externally focused (Morris et al. 2005). To search for CEOs, we use the terms “Chief Executive Officers,” “CEO,” CEOs,” or “leaders.” To search for the humility construct, we use search strings such as “humility” or “humble.” We then use Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” to link both terms. After this stage, we compare the results with the VHB- JOURQUAL 3 ranking (“A” and “B” ranked), a German journal ranking with great overlap to comparable rankings in other countries (e.g., CABS, United Kingdom). This leads to the exclusion of certain practice-orientated outlets (e.g., Harvard Business Review) but to the inclusion of core Management outlets (e.g., Academy of Management Journal, Strategic Management Journal, Leadership Quarterly, Organization Science, Journal of Applied Psychology) as well as specialized Management outlets (e.g., Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Business Venturing). After this round, we scan all papers for the level of analysis qualitatively and exclude papers that are (1) review articles (e.g., servant leadership: van Dierendonck 2011) and (2) that are theoretical in nature without an empirical basis (Argandona 2015; Morris et al. 2005). For instance, the review by van Dierendonck (2011) on servant leadership would not be included in the more conservative string using “CEO” as the level of analysis, but would be included in the more general search string “leader.” In addition, including possibly higher-order constructs such as servant leadership composed of several equal dimensions (e.g., stewardship or authenticity) would dilute the meaning of a single construct such as humility. Hence, possibly inflating the number of articles. Similarly, conceptual articles such as Morris et al. (2005) are implicitly part of the theory, but would inflate the fine-grained analysis of the empirical articles. These restrictions led to a final sample of 17 articles we analyzed for the review. This number is smaller than other literature reviews (e.g., 35: Kubíček and Machek 2019) as the provided study here focuses on (1) empirical articles and (2) imposes a conservative journal threshold. Although this is in line with previous research (e.g., Bolino et al. 2008), we recognize that this focus on very selective journals and externally, quantitatively metrics such as journal lists may penalize excellent research from authors in other journals. In addition, we derive the humility keywords from prior literature that indicates that humility is distinct from constructs such as modesty. However, we check for the possibility of synonyms that may affect the search string. We use the thesaurus homepage collinsdictionary.com to search for synonyms of “humility.” We export the top five synonyms, namely “modesty,” “diffidence,” “meekness,” “submissiveness,” and “servility,” and apply the search thresholds as above. The extra search reveals one additional study that would fit with the time and journal threshold, namely Hill et al. (2018). After a careful analysis of the article, we decided to exclude the article as it covers a different construct with no reference to humility-related literature. The fact that we find no articles with words such as “diffidence” or “meekness” with the CEO as a level of analysis indicates that our search procedure is sufficiently broad to incorporate possible synonyms and that this is not just motivated by theoretical reasoning. Moreover, the relatively low number of analyzed studies may rather reflect the lack of attention towards the construct within top-tier Management outlets at the moment. We further discuss the distinctions between constructs in the discussion of the results section. An overview of these articles can be found in Table 1. After providing an overview of the various insights from the Strategic Management, Strategic Leadership, and Organizational Behavior literature, we integrate the research findings into a comprehensive framework in Fig. 1. This is meant to provide a thematic list for researchers on the status quo of this research.

In the following discussion, we employ the term “general” literature and “analyzed” literature to contrast evidence from Social Psychology with evidence from our selection procedure embedded in the Management literature. Given the possibility that humility may overlap with other constructs (e.g., Tangney 2002) and the empirical evidence in the synonymous search that humility is linked in everyday language with constructs such as modesty, we also employ a key word search of conceptually related constructs across all identified CEO humility studies and discuss the results in the respective section. After finishing the search and identification procedure, the two authors independently coded the selected articles. Using the classical framework of Podsakoff and Dalton (1987), we coded the “Nature of Results Verification” (whether the authors used cross-validation, subgroup analyses, factor analyses, etc. for their verification); the “Level of Analysis” (whether the authors used an individual, organizational group level, etc.); the “Type of Dependent Variable” (whether the authors used performance, perceptual, attitudinal, etc. as dependent variable); the “Primary Means of Data Collection” (whether the authors used questionnaires, laboratory tasks, etc.); the “Nature of Construct Validation Procedure” (whether reliability or interrater validity, etc. was checked). For instance, Ou et al. (2016) will receive a code for “Type of Dependent Variable” for “performance” as they employ firm performance in the form of Return on Assets (ROA). The authors also employ the Owens et al. (2013) Likert scale to measure CEO humility so that they will receive a code for “Primary Means of Data Collection” for “questionnaires.” The authors report on convergent validity (Owens and Hekman 2016, p. 1158) by comparing self-reported humility scores with humility scores issued by CFOs so that the article will receive a code under “Nature of Construct Validation Procedure” for “Discriminant/Convergent/Predictive Validity.” The article will receive a code under “Level of Analysis” for “Mixed” as the independent variable is measured on an individual level while the dependent variable firm performance is measured on an organizational level.

We aggregate the absolute codes as studies may use different means of data collection or dependent variables and relate it to the overall number of studies. The results of the coding procedure can be found in the “Appendix”. The coding is not meant to replace a thorough analysis of the articles and the field but to provide a stylistic overview of important aspects of the analysis based on criteria relevant to scholarly probing (Podsakoff and Dalton 1987). For instance, the analysis in “Appendix” Table 5 indicates that the dominant means of data collection is via questionnaires, while other means such as behavior recording, nominal groups/Delphi, or naturally occurring field experiments received no attention. We further discuss the implications of the analysis in the results section as well as in the future research section.

5 Discussion of the results

After reviewing all the selected studies, Owens and Hekman’s (2012) study can be considered the first, large-scale inductive study to show how leader expressed humility affects follower outcomes and contingencies. They show how expressed humility manifests in leaders mainly by acknowledging mistakes, limitations, and faults, highlighting follower contribution, strengths and teachability, consequences for follower outcomes (e.g., psychological freedom), and consequences on the leader–follower relationship (e.g., trust and loyalty-building). The main attributed characteristic of a humble CEO is his or her openness to new ideas and feedback and that they listen before they speak (Owens and Hekman 2012). As a follow-up study, Owens et al. (2013) attempt to develop a scale to directly conceptualize and measure humility in a variety of samples (see the procedure in Table 1). We find that a majority of subsequent articles employ this measure. The authors define expressed humility as an interpersonal characteristic that emerges in social contexts comprising (a) a manifested willingness to view oneself accurately, (b) a displayed appreciation of others’ strengths and contributions, and (c) teachability. According to the authors, willingness to see oneself accurately leads to balanced or more accurate self-awareness that helps organizational members and leaders know more accurately when to take action and learn more about an issue, thereby preventing overconfidence. Appreciation of others will help CEOs to more readily identify and value the unique abilities and strengths of those with whom they work by rejecting simplistic, binary evaluations of others but by having a complex view of others (e.g., seeing a variety of character strengths and skills) (Owens et al. 2013). According to the authors, teachability will lead CEOs to show openness to learning, feedback, and new ideas from others by showing receptiveness to others’ feedback, ideas, and advice and the willingness to ask for help; this can be seen as essential in risky, innovative endeavors.

Owens et al. (2013) developed the scale by using exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis in two other samples. Consequently, for instance, questionnaire items 1, 2, and 3 reflect a willingness to view oneself (e.g., item 1: “This person actively seeks feedback”). The reliability for the resulting expressed humility scales was Alpha = 0.94 and was confirmed by ten content experts. Therefore, the Owens et al. (2013) scale can be seen as a state-of-the-art scale to directly assess leader expressed humility. The measure can also be used in experimental or semi-experimental conditions that are well suited to circumvent the CEO humility-outcome relationship's potential endogenous nature and build needed cumulative evidence on CEO humility (e.g., Antonakis 2017). Although the scale is validated and widely used by subsequent papers, the authors focused on expressed (i.e., observable) humility. Approaches to gauge intrapersonal aspects (e.g., emotion processing) of CEO humility are – compared to expressed humility – limited. Therefore, Ou et al. (2014) developed the scale of CEO humility by building on the items of Owens et al. (2013). The authors extend the dimensions and items to self-transcendent pursuit (e.g., “My CEO has a sense of personal mission in life.”) and transcendent self-concept (“My CEO believes that not everything is under his/her control.”) that can be used for future research. Other dimensions include “low self-focus,” and corresponding scales such as “My CEO does not like to draw attention to himself/herself.”

Generally, we find the full spectrum of approaches and methods ranging from inductive qualitative research (e.g., Owens and Hekman 2012), direct assessment (questionnaire: e.g., Rego et al. 2017b), experimental (e.g., Owens and Hekman 2016) as well as indirect (unobtrusive) assessment of humility (e.g., Petrenko et al. 2019). Given the potential conceptual (e.g., Tangney 2002) and empirical overlap of humility with related constructs, we next proceed with a discussion of the reviewed articles in Management research and analyze whether or how the studied articles discuss related constructs compared to the general literature. For instance, we employ a key word search for the assumed construct at hand across the analyzed humility articles.

6 A discussion on differentiating humility from related constructs in social psychology

6.1 Narcissism and dark traits

The general Social Psychology literature on humility is based on the HEXACO scale and two alternative measures of narcissism: narcissistic personality inventory (NPI) and narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) suggest moderate to strong negatively correlated items (r = − .63 and r = − .58), although these studies only consider vulnerable narcissism and are limited to small sample sizes (Miller et al. 2009). Particularly modesty (r = − .71 and r = − .62) and greed avoidance (r = − .54 and r = − 54) appear to be particularly strong negatively correlated sub-dimensions. Aghababaei et al. (2014) find high negative relationships between the dark traits (Machiavellianism, Psychopathy, Narcissism) and honest-humility (r = − .59, p < .01), with narcissism showing moderate negative relationships (r = − .36, p < .01). Banker and Leary (2019) find high negative relationships between narcissism and humility (r = − .61, p < .01). The authors also find that humility and self-esteem were uncorrelated. The authors controlled several measures using a general measure of humility (BHS, Kruse et al. 2016), the HEXACO, and the Dual-Dimension Humility Scale (DDHS) that consists of religious humility, cosmic humility, environmental humility, other-focus, and valuing humility. Narcissism (egoistic entitlement) strongly correlated negatively with all scales with the BHS (r = − .64, p < .01), all subscales of the Honesty-Humility Scale (HH-modesty: r = − .65, p < .01), and the DDHS valuing humility subscale (r = − .22, p = .01). Similarly, Lee and Ashton (2005) find that narcissism and honest-humility (r = − .53, p < .01) are moderate to strongly negatively related.

These approaches seem to confirm Management related research that depicts dark traits (in particular narcissism) and humility as negatively related. Interestingly, management research favors a dominant approach to measuring humility via the Owens et al. (2013) scale. In contrast, the general literature indicates more nuanced measures of humility, such as the BHS (brief humility scale) and DDHS (Dual-Dimension Humility Scale). However, all measures indicate a strong negative relationship with narcissism regardless of the measures. Therefore, humility in the general Social Psychology literature can be seen as low narcissism with reversed coded scales of narcissism as indicators of humility. However, in line with the philosophical assumption of Positive Psychology (Davis et al. 2010), we believe that the absence of something negative does not necessarily imply the presence of something positive, whereby humility is not just the absence of dark traits such as narcissism. The Management literature argues that narcissism and humility are more distinct, and that narcissism is not necessarily related to humility. The inflated self-view of narcissists drives them to desire personal recognition and glory with the need for constant reinforcement through external stimuli via bold and dramatic behaviors that draw attention from external gatekeepers (Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007; Gerstner et al. 2013). In our analyzed literature, Owens et al. (2015) find .00 or − .06 correlations, Ou et al. (2014) found − .08 or − .24 correlations, and Zhang et al. (2017) find − .07 correlations. These low correlations indicate that narcissism and humility are not just reversed scales and therefore distinct constructs, making sub-facets of humility such as appreciation of others or self-transcendent pursuits theoretically and empirically distinct. Consequently, it might be better to treat narcissism and humility as predictors or as interaction terms.

7 Big five and five-factor-model (FFM)

The general literature (e.g., Ashton and Lee 2005) on humility and the big five indicates only moderate relationships as even its strongest correlations only reached the .20 s (r = .26 for Big Five Mini‐Marker Agreeableness, r = .28 for IPIP Big Five Agreeableness). The FFM (NEO PI-R) shows higher overlap, in particular, Agreeableness (r = .54) as the only trait with a higher than .20 correlation, thereby incorporating a large element of Honesty‐Humility variance. Other studies find that honesty-humility is related to Agreeableness (r = .63, p < .01) and as a second highest correlate, to Conscientiousness (r = .55, p < .01). Hilbig et al. (2013) find only moderate correlates with Agreeableness (r = .17, p < .01) in their experimental study (dictator game), while only honest humility and not Agreeableness predicted cooperative behavior, supporting the assumption that humility is moderately linked to some higher-order personality traits (Agreeableness) but has sufficient potential to explain the variance of outcome variables. Individuals with low honest-humility scores tend to allocate more scarce resources to themselves, while high score individuals tend to allocate resources fairly (Hilbig and Zettler 2009). People with lower honest-humility scores had higher creativity scores (Silvia et al. 2011). Based on this evidence, individual effects of humility are that those individuals who exert higher levels of humility tend to be more trusting and more likely to be perceived as cooperative, investing more in the social good instead of their own utility maximization.

In our analyzed literature, Owens et al. (2013) argue similarly that traits such as openness to experience represent general interpersonal traits that are not necessarily tied to interactions with others. Owens et al. (2013) find expressed humility to be only moderately positively correlated with Conscientiousness (r = .28, p < .01), Openness to experience (r = .31, p < .01) and Emotional stability (r = .49, p < .01). Vries (2012) compares honest-humility scores with self-rated personality scores of leaders as well as subordinate rated scores of leadership. De Vries finds that honest-humility is linked to self-rated Emotionality (r = .40, p < .01) as well as Agreeableness (r = .30, p < .01) as well Conscientiousness (r = .32, p < .01). Self-rated honest-humility and subordinate rated Honest-Humility appears to be positively associated (r = .41, p < .01) while positively associated with self (r = .63, p < .01) and subordinated rate ethical leadership (r = .31, p < .01). In total, our analysis suggests significant but not very strong relations between leaders' self-rated personality and subordinate-rated leadership and that humility is linked to actual leadership style. We find that the moderate positive correlations (e.g., Owens et al. 2013) overlap with the prior conceptualizations of teachability (Tangney 2000) which is manifested by showing openness to learning, feedback, and new ideas from others, thereby translating, for instance, to higher Big 5 values such as openness to new experiences. However, the results do not explain sufficient variance to conclude that all Big 5 traits make humility replaceable as a construct.

8 Honesty-humility

To test whether humility is distinct from a commonly used measure in the general literature, Honest-Humility, Owens et al. (2013) argue that Honest-Humility represents an important prosocial characteristic but lacks the key dimensions of humility such as willingness to view oneself accurately, teachability, and appreciation of others. Empirically, Honest-Humility and expressed humility are positively related (r = .55, p < .01), confirming the theoretical assumption that the dimensions of Honest-Humility (Sincerity, Fairness, Greed Avoidance, and Modesty) and humility overlap but are distinct.

9 Modesty

In the general literature, Davis et al. (2010) argue that modesty and humility only overlap on the dimension of having a moderate or accurate view of the self, while other aspects of the humility definition, namely acknowledging limitations, openness to new ideas, the perspective of abilities and accomplishments in relation to the big picture, a low self-focus, and a valuing of all things, do not show an overlap.

Davis et al. (2015) find that general modesty showed one of the stronger factor loadings on the higher-order factor Relational Humility Scale (RHS), supporting the idea that modesty is a subdomain of humility. In total, the general literature argues that modesty is theoretically distinct, while empirical results show that modesty is at least a domain to consider. Our specific literature indicates that modesty is an important construct to consider. For instance, Oc et al. (2015) derive inductively dimensions from Singaporean leaders; “showing modesty,” “working together for the collective good,” “empathy and approachability,” “showing mutual respect and fairness,” and “mentoring and coaching” are key dimensions of the leadership style. Similarly, Owens et al. (2013) find a high overlap (r = .62, p < .01) between modesty and expressed humility and argue that humility differs from modesty in terms of individual motivation for personal learning and development.

10 Self-esteem

The hypothesis that humility is linked with low self-esteem has been intensively employed (Tangney 2000, 2002). The general language indicates that self-reported humility correlates positively with self-reported self-esteem and that implicit humility and implicit self-esteem were positively related (Rowatt et al. 2006). Self-reported humility positively correlated with self-reported satisfaction with life (partial r = .29, p < .05), Rosenberg self-esteem (partial r = .25, p < .05), while no association was found between depression or poor health (Rowatt et al. 2006). Weidman et al. (2018) examine two distinct semantic clusters, one related to the appreciation of others and a desire to be agreeable, and the other involving signs of self-abasement, low self-esteem and shame, and a desire to withdraw from social situations, thereby also indicating that there is a downside to humility. The authors coin the clusters appreciative and self-abasing humility. In particular, the correlation between self-abasing humility and self-esteem was moderate and negative (Weidman et al. 2018). Our specific literature indicates only a moderate positive correlation with a higher-order construct (core-self-evaluation, r = .34, p < .01) and humility, indicating a distinct construct.

11 Impression management (IM)

The general literature on humility and impression management shows an inverse relationship between both constructs, meaning that individuals low in this trait were more likely to report using all five chosen IM behaviors (Bourdage et al. 2015). This aligns with the definition of humility, whereby individuals who engage in IM tactics such as ingratiation are not humble. However, the study also indicates that coworkers poorly judge colleagues' tactic use and the Honest-Humility scores. This contradicts the potential argument that the humble trait is itself a form of IM tactic. This is confirmed in a Dutch sample (N = 1106), whereby IM tactics (r = − .14) are negatively related to honesty-humility (Vries et al. 2014).

12 A discussion on humility measures

Interestingly, our analysis indicates that management research provides much less variance in terms of methods. Whereas Social Psychology studies report up to 22 measures (McElroy-Heltzel et al. 2017), our Management studies tend to employ either direct assessment via questionnaires (e.g., Rego et al. 2017b) or indirect (unobtrusive) assessment of humility (e.g., Petrenko et al. 2019).

In total, the Owens et al. (2013) scale appears to be the mode of choice when studying humility in leaders as it has been extensively used in top-tier journals. We find that the construct has been used in different contexts, different samples (e.g., full-time employees, in the commercial subject pool, employees of a health organization, upper-level undergraduate students) and across time, suggesting stable validity properties (discriminant and convergence) as well as reliability properties. It has also been used to assess individual level as well as collective humility assessments. The expressed humility construct and scale was predictive of team contribution ratings and individual performance beyond the related constructs of core self-evaluation and openness to experience and the common performance predictors of self-efficacy, conscientiousness, and general mental ability. The authors also show that CEO humility remains predictive when controlled for Honesty-Humility, learning goal orientation, Big Five, modesty, narcissism, and core self-evaluations. Hence, we conclude that the scale provides a state-of-the-art tool for researchers in organizations and should be at least a benchmark to verify own measures in Management studies.

In contrast, the general literature on humility provides much more variance in measures of humility. McElroy-Heltzel et al. (2017) recently reviewed general measures of humility and concluded that the Relational Humility Scale (RHS) is best suited for general Social Psychology research (relationships). Banker and Leary (2019) also study humility scales and find that the brief humility scale and the Honest-Humility scale strongly correlate (r = .56, p < .001), while the DDHS shows only moderate (r = .27, p < .001) positive relationships with the BHS and the HH total (r = .22, p = .001), indicating a much higher variance of methods and a lack of a dominant measure across the general literature.

13 A discussion on methods

A popular approach in the literature is to assess humility via self-reports such as HEXACO scales. However, high self-reports on humility may ironically indicate a lack of humility due to a social desirability bias and because humble individuals do not publicly have the desire to label themselves as humble. In addition, Davis et al. (2010) note that HEXACO-PO items lack face validity and do not fully align with how humility has been defined. We find that most studies employ a framework with a questionnaire method. An overview of the primary means of data collection can be found in Table 5 in the “Appendix”, with no attention to naturally occurring field experiments, behavior recording, or nominal groups/Delphi. Just a few papers utilize other primary means of data collection, such as an experimental approach. For instance, Rego et al. (2017b) provide participants with a description of a potential supervisor who shows signs of theoretically derived dimensions (willingness to view oneself accurately, appreciation of others’ strengths, and teachability based on Owens et al. 2013). Participants were told that their direct supervisor is very aware of their personal strengths and weaknesses, appreciates their unique contributions, and often compliments others on their strengths and qualities. The control condition received a scenario with a transactional leader. This setting is also used to control in a standardized manner for cultural effects, indicating that experimental settings are indeed possible. This is in line with current developments in the leadership literature to model hard-to-measure constructs as experimental settings (Antonakis 2017; Antonakis et al. 2015, 2011). Given this evidence, we believe it is important to increase settings' heterogeneity and use experimental settings to exclude alternative explanations for humility. Moreover, given the trend in organizational studies toward unobtrusive measures (Webb 1966), we believe that the humility field lags behind similar hard-to-measure constructs in organizational studies. For instance, Chatterjee and Hambrick (2007) provide a combination of several related and unrelated unobtrusive measures such as the pay gap in the TMT or the size of the picture in the annual report to construct their measure of narcissism. The study provided a blueprint for subsequent studies in the field (e.g., Buyl et al. 2017). We see no reason why studies of humility should not make use of unobtrusive measures, including the validation procedure as suggested by this literature (Buyl et al. 2017; Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007). In line with the argument for a greater need for unobtrusive measures, one avenue of research would be to increase attention toward the language of CEOs. Previous research finds that CEO language can be reflective of personality (e.g., Akstinaite et al. 2019; Craig and Amernic 2011, 2016); one could analyze qualitatively how humble CEOs express themselves across several organizational narratives such as conference calls or shareholder letters. Alternatively, the growing literature on computer-aided-content-analysis (Short et al. 2010, 2018) suggests that linguistic cues of CEOs can be effectively analyzed using psychometrics (e.g., Baur et al. 2016; Patelli and Pedrini 2015) or stand-alone dictionaries (e.g., Gamache et al. 2015). Therefore, a validated dictionary of CEO humility validated on a CEO level would be a major step towards a key unobtrusive measure.

14 A discussion on demographic, structural, and industry variables

As previously mentioned, we provide an overview of constructs relevant to the emergence of leader humility as well as its consequences (Fig. 1). However, we also elaborate on theoretical variables that were hypothesized to be relevant to humility but do not show a relationship. For instance, one may argue that the gender of the leader is relevant to humility as humility developments are embedded in child development processes and socially constructed role expectations. Similarly, one may argue that larger groups are problematic for leader humility as coordination costs and role conflicts increase. However, in the field study, Owens and Hekman (2016) do not find a significant relationship between gender, age, team size, and humility. However, they find a negative relationship between team size and collective humility (r = − 34, p < .05). Zhang et al. (2017) find almost no connection between CEO age (r = − .15), CEO education (r = .06), CEO gender (r = .07) with p > .10 levels, and CEO humility. Similarly, Mao et al. (2018) find no significant connection between leader humility, follower age, follower gender, leader age, and leader gender. Ou et al. (2016) find no significant difference between CEO humility and CEO tenure as well as CEO functional background (finance and accounting; operation dummy). In contrast, Zhang et al. (2017) find positive but small effects on CEO tenure (r = .23, p < .10) and CEO humility. Petrenko et al. (2019) find no connection between CEO humility and CEO age, CEO tenure, CEO duality (if the CEO is also Chairman of the board), as well as CEO gender. Similarly, Hu et al. (2018) test leader gender (male/female), team tenure, and team size to be unrelated to leader humility. Oc et al. (2015) test for gender differences and find generally similar results across gender, with the exception that female respondents were more likely to mention sub-dimensions of humility such as “having an accurate view of self” than males (9.28% and 3.99% respectively). Female participants were also more likely to mention “recognizing follower strengths and achievements” more than males (11.38% and 5.98%, respectively), suggesting that gender plays a role in the perception of the sub-dimension of humility.

Oc et al. (2015) find that across all age groups, “modeling teachability and being correctable” was the dimension of humble leader behaviors mentioned most frequently. Surprisingly, there are only slightly different patterns between oldest (> 50) and youngest (20–30) age groups on most dimensions. The older the participants are, the less frequently they mentioned “having an accurate view of self,” but they more frequently mentioned, “empathy and approachability.” The authors suggest that age may be an important factor affecting the perception of leader humility, but it did not show a clear pattern.

Oc et al. (2015) test also for industry effects of perceived humility and find that respondents in manufacturing industries “empathy and approachability” accounted for the second-largest percentage of statements (16.95%), whereas for respondents in governmental positions, “showing mutual respect and fairness,” was the second most important dimension (19.44%). Although some industry variables contain a very limited number of participants (Transport n = 9; Human Services n = 10), these results indicate that industry potentially plays an important role in determining perceptions of humility.

Generally, most studies in our review find limited evidence of CEO humility and demographic variables of CEO age, CEO educational background, and CEO gender, suggesting that humility is a rather time-stable disposition independent from gender and experience effects across life. Similarly, we find limited evidence on firm-level variables such as company size or industry effects on CEO humility. This is surprising but might be related to the fact that just one study employs a large-scale, multi-industry approach (Petrenko et al. 2019), while some studies employ medium-sized enterprise samples (Ou et al. 2016) or specific samples in China (Zhang et al. 2017). Only one study reaps the strengths of the rigor and internal validity of laboratory contexts as well as the power and generality of field contexts in experiments (Owens and Hekman 2016). Figure 1 provides a thematic overview, including the antecedents and consequences of the CEO humility literature. The overview provides an integrative framework.

15 A discussion on content trends

Research on humility on a leader level appears to confirm positive effects on individual and team-level constructs. We find that a majority of studies employ as a level of analysis an individual-level approach (63.64%), while only a few studies used a mixed level of analysis (4.55%; see Table 3 in the “Appendix”). For instance, expressed leader humility directly corresponds to higher levels of job engagement (.25, p < .01) and job satisfaction (.44, p < .01) and negatively to voluntary turnover of subordinates (− .14, p < .01) (Owens et al. 2013). Expressed humility showed a significant positive relationship with team contribution (r = .331 p < .01) and individual performance (r = .051, p < .01) and remained highly significant in the Ordinary Least Squared regression after controlling for constructs such as core self-evaluation and openness to experience (Owens et al. 2013).

In addition, Hu et al. (2018) find that humble leaders facilitate safe psychological environments for teams and foster team information sharing; both aspects are crucial for innovation outcomes characterized by heightened risk and uncertainty. Mao et al. (2018) find that leader humility is linked to follower self-expansion, self-efficacy, and task performance. In addition, this is moderated by the demographic similarity between leaders and followers. Similarly, Rego et al. (2017b) find a positive relationship between leader humility and team psychological capital. The authors use three studies in different contexts, including an experimental approach to analyze the relationship between leader humility and team performance. The field study (study three) confirms strong, moderate associations between followers who reported leader humility; followers reported team psychological capital (r = .41, p < .01), and subsequent leaders reported team performance (r = .31, p < .01), indicating that team performance is not affected directly but via psychological processes such as team task allocation effectiveness or team psychological capital. Rego et al. (2017a) confirm the results in the moderated mediated relation between leader humility, collective humility, and team psychological capital.

Owens and Hekman (2016) find in their mediation model that leader humility spills over to collective humility, which in turn affects the team's collective promotion focus as a consequence, positively affects team performance. We believe that the idea of a two-sided study, as in Owens and Hekman (2016), is beneficial to future studies whereby leaders must act as role models of their own humility that enables the construct to spill over to the team. This may help researchers better understand why an individual-level construct (leader humility) affects organizational level constructs such as firm performance via team levels such as collective humility. Ou et al. (2014) show that CEO humility contributes indirectly to a team-level construct, namely TMT integration that consists of joint decision making, information sharing, collaborative behavior, and a shared vision within the TMT. Jeung and Yoon (2016) find that leader humility affects the ability of followers to embrace the individual subjective psychological experience of being empowered. Ou et al. (2018) show that CEO humility affects organizations indirectly as humble CEOs manage to do so through TMT integration and pay equality.

Inductive results by Owens and Hekman (2012) also show that expressed humility contributes to leader perception regarding leader competence and leader sincerity. Though humble signs such as admitting weaknesses were described as a unique type of strength, the study participants insisted that more traditional leadership traits, such as intelligence, resolve, and persuasiveness, needed to work in combination with humility for the leader to be perceived as an effective leader. Interestingly, participants acknowledged the possibility that the trait can be faked for their own benefits, but incongruent behavior will be detected by subordinates and colleagues in the long term (Owens and Hekman 2012, p. 798). Therefore, given the previously cited references, the magnitude and number of positive effects of individual humility on team processes are surprisingly high.

Compared to a team level, we find only three articles directly studying the effects of direct CEO humility on organizational outcomes. These articles show the positive yet indirect effect of CEO humility on organizational outcomes. For instance, Ou et al. (2016) conclude that CEO humility does not affect firm performance (Return on Assets) directly but via a mediation model of increased information sharing in the TMT. The authors conclude that “humble CEOs do not stress power over other TMT members but, instead, have the power to pursue goals for collective interest with the TMTs” (Ou et al. 2016, p.3). Furthermore, the authors find that the pay gap between TMT and CEO is decreased, which can be seen as the main manifestation of CEO humility in organizations. These results of CEO humility on firms’ strategic decisions appear to confirm previous theoretical and anecdotal research (e.g., Collins 2001).

Interestingly, Zhang et al. (2017) do not find a significant correlation between CEO humility and direct firm innovative culture but find a positive and significant relationship when narcissism was high (interaction effect), suggesting humility and narcissism interact together and can be possessed at the same time. This article appears to be one of two articles simultaneously analyzing CEO narcissism and CEO humility (Owens et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2017). Zhang et al. (2017) find that CEO narcissism measured via the Narcissistic Personality Inventory-16 (Ames et al. 2006) and CEO humility measured via Owens et al. (2013) are not directly related, thereby rejecting the hypothesis that both constructs are two ends of one continuum. Owens et al. (2015) use the same measures for CEO humility and CEO narcissism and find that “humility will help to buffer the effects of the most toxic, demotivating dimensions of narcissism, while allowing the potentially constructive or motivating aspects of narcissism to arouse employees, create perceptions of leader effectiveness, and foster a sense of supportiveness […]” (Owens et al. 2015, p. 1205). Therefore, the authors also find that narcissism and humility are not directly related (non-significant bivariate correlations), but the interaction term predicted important outcomes (e.g., perceived leader effectiveness). Therefore, we urge future research to assess CEO narcissism and CEO humility to disentangle both constructs, either as interactions but at least as controls. This is important because CEO humility could be conceptualized as a lack of ambition and initiative (Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007).

Finally, Petrenko et al. (2019) find that CEO humility affects market performance positively of all market measures (i.e., Abnormal Returns, Tobin's Q, Total Shareholder Returns) but not operational performance (i.e., Return on Assets). Abnormal returns increase up to 22 percent for every standard deviation of CEO humility. This discrepancy can be explained by analysts' dampened earnings per share (EPS) estimates and firms' actual EPS, leading to positive market performance. The authors' results indicate that companies with humble CEOs receive lower ratings by analysts ex-ante, suggesting that when humble CEOs do not fit in the heuristic social role expectations of certain key stakeholders, they are ultimately punished through dampened earnings estimates. Since the subjective evaluations of key stakeholders such as analysts or journalists are important for companies, we urge future research to incorporate a perceived third-party rating as a complement of direct humility. CEO humility may be better captured through perceived market evaluations that include analysts’ expectations than classical archival-based performance measures. Therefore, the study of Petrenko et al. (2019) reminds us of the potential “negative” effects of CEO humility that can take place not via organizational processes but via external perceptions. However, we expect third-party evaluations by journalists, analysts, or board of directors to adopt a more nuanced, complex, and less heuristic view about CEO traits as research results spill over into practice. Generally, we find the type of dependent variable to be heterogeneously distributed between performance (30.43%), Perceptual (30.43%), and Attitudinal (34.78%; see Table 4 in the “Appendix”). Therefore, we see major opportunities in linking CEO humility to actual firm outcomes as a dependent variable, similar to previous studies on hard-to-measures constructs (Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007) as well as humility (Ou et al. 2016). However, a guiding question for researchers in the field remains whether the results of CEO humility hold true not just in small-and-medium companies in certain industries such as hardware (Ou et al. 2016) but can be generalized to the public companies across industries.

On the other hand, research on the direct level of the CEO is rather scarce. Given the overall positive effects we find on team processes, it is interesting to analyze whether these team processes translate into organizational outcomes (e.g., via moderating/mediating mechanisms). This might be related to the fact that the conceptualization of the level of analysis tends to be vague in some cases. For instance, Hu et al. (2018) report the demographic characteristics of “leaders” (average age of 33 years, 53% female, 99% had a college degree, average tenure in leadership positions of 35 months), but it remains unclear how exactly “leaders” are defined. Future research should be precise about the level of analysis and should address the question of whether different leadership hierarchies (e.g., middle management) can be generalized to the upper echelon (i.e., CEO).

A reason for the few results on a direct CEO level compared to other leader levels might be the lack of access to large-scale data of CEOs. Since it is difficult and laborious to assess directly CEOs, only one study employed unobtrusive measures of CEOs (Petrenko et al. 2019). This is surprising given that Chatterjee and Hambrick (2007) showed that CEOs' unobservable characteristics can be evaluated using publicly accessible data and subsequent papers followed suit (e.g., Buyl et al. 2017; Gerstner et al. 2013). Therefore, the video metric approach (Petrenko et al. 2019) appears to be the only article using unobtrusive measures and enables researchers to study CEOs without direct access. We urge future research to employ either unobtrusive measures or—as some studies do (Rego et al. 2017b)—a combination of directly established humility scales (e.g., Owens et al. 2013) and indirect assessment through subordinates or members of the TMT, which might be easier to access.

Furthermore, the grounding of many analyzed studies in eastern samples (Cheung and Chan 2005; Hu et al. 2018; Oc et al. 2015) points to the role of cultural values in which Confucian values carry heightened importance toward humility. For instance, Cheung and Chan (2005) argue that all interviewed Chinese CEOs answered based on Confucianism values that advocate benevolence, righteousness, harmony, loyalty, humility, and learning. Making use of each employee’s unique talent and admitting personal shortcomings (e.g., lack of technical competence) was an approach used by all five CEOs and a reported key ingredient of their leadership styles (Cheung and Chan 2005). Future studies may tackle this by directly drawing from western and eastern samples.

16 The future of CEO humility research

In total, the overall evidence presented in this study indicates that CEO humility has direct positive effects on a number of direct team processes and indirect positive effects on a number of key organizational outcomes (e.g., market performance, compensation gap between CEO and team members). This holds true for both subjective team performance measures (Rego et al. 2017a) and objective measures of firm performance (Ou et al. 2016). Furthermore, as indicated in Fig. 1 and the discussion, CEO humility affects personal outcomes such as intellectual openness, team processes such as team psychological safety, team psychological empowerment or team learning, and organizational outcomes such as ambidextrous orientations. This is counterintuitive from an economic point of view, but seems to confirm calls in the literature to devote more attention to CEO humility (e.g., Argandona 2015) as well as confirms Social Psychological literature on humility (Davis et al., 2010; Wright et al., 2016). Given the prior calls in the literature and these “promising” signs of humility in the Management literature revealed in this review, we expect the overall number of humility studies to steadily increase in the next years. Moreover, given that we identified the article by Owens et al. (2013) as one of the first important empirical CEO humility articles, one should be aware that the field is still in its infancy. Compared with highly cited Management articles on similar hard-to-measure constructs such as narcissism (Chatterjee and Hambrick 2007), we believe that research on humility can catch-up quantitatively in the next years and could receive similar attention.

On the other hand, there are also first, although fewer, signs that CEO humility can have partial drawbacks for organizations. For instance, younger CEOs need to build up or establish a reputation for competence before admitting weaknesses as the main dimension of CEO humility (Owens and Hekman 2012). These contradictory results point to the fact that it is of great importance for future studies to address the different mechanisms underlying actual and perceived humility clearly and employ longer time periods to detect developments of CEO humility over time. We see the incorporation of perceptual scales as one major avenue to further enhance our understanding of humility and understand the potential negative effects of humility. This is important because the perceived evaluation of key stakeholders (e.g., analysts) may follow a heuristic perception of “strong” and “loud” CEOs, which would counteract humility traits. Consequently, deviation from this biased perception may lead to dampened evaluations of CEOs, which is critical because organizations rely on external evaluations to obtain resources (e.g., Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). Leaders should be aware of different assumptions, expectations, and perceptions of different stakeholder groups possess, indicating that CEO humility (and narcissism) are also situational traits that can be “employed.” Therefore, examining CEO humility's perceived and actual “negative” effects can be another major avenue for research, as western societies appear to follow simplistic and heuristic expectations about CEO traits. When selecting potential leaders (e.g., CEOs), members of organizations (e.g., Board of Directors) should be aware of imprinted societal values that may bias their judgment. Hence, a general focus on nuanced detrimental effects of CEO humility may enable future researchers to differentiate themselves. Moreover, perceptual scales of third parties such as employees may be important for future research as more humble CEOs may be viewed as “weak” by stakeholders.

Our review also indicates that humility is more likely to affect organizations indirectly and that humility does not directly affect firm performance but via mediating mechanisms. For instance, we were surprised to find that CEO humility appears to be not directly (i.e., non-significant) related to CEO demographic information such as age, gender, or education (also see Fig. 1). In addition, organizational factors such as firm age or firm size appear not to affect CEO humility directly (i.e., non-significant). This may suggest that, although the firm size and firm age may be conducive to CEO humility, we may overestimate the factors enabling humble CEOs to thrive, suggesting that humble CEOs can be found or developed in any kind of organization. Given these results, we hope future research on CEO humility focuses on smaller companies in their sample selection although this may require a change in the method. A shift towards smaller companies in the sample selection and more qualitative methods may increase the diversity of methods as they are at the moment dominated by large scale-quantitative methods based on unobtrusive measures. Whereas we see for a need of a more diverse method toolbox, we also acknowledge the presence of quantitative, indirect measures of CEO humility that are likely to increase due to their unique features alongside qualitative approaches.

The review suggests that selecting and employing relatively more humble leaders may have at least two direct consequences for organizations. First, more humble leaders create an atmosphere of increased personal openness and psychological safety for subordinates and teams. Second, employing more humble leaders may enable organizations to avoid certain organizational practices that go against the legitimate interest of an organization. This is similar to current meta-analytical evidence seeing Honest-Humility as a strong direct predictor of counterproductive work behavior after controlling for other established individual differences predictors (e.g., FFM traits, integrity tests; Lee et al. 2019). Given these first direct consequences of CEO humility, future research should pay increased attention to indirect consequences of CEO humility. This is often accomplished by incorporating additional moderator/mediator variables and by using more than one data source, thereby further increasing the level of research complexity and resource intensity. However, given the dominance of a certain means of data collection (see “Appendix” Table 5), we hope that these hints may enable future research to reveal more indirect consequences of CEO humility. The results of our review also indicate that individual-level humility is less likely to affect direct organizational outcomes but via mediating mechanisms. Mechanisms include psychological empowerment or psychological safety that can take place on an individual and a group level. Therefore, we urge future research to consider these mediating mechanisms and designs that capture several levels of analysis and thus bridge the macro/micro divide. Based on the provided results in the review, we believe that many organizational outcome variables (e.g., firm performance) are too distal to show a significant effect; rather, we urge future research to explore alternative designs (e.g., experiments) and/or analyzing moderating and mediating mechanisms of CEO humility that can be found in the voluminous upper echelon theory (Hambrick and Mason 1984). As an example of indirect effects found in the upper echelon theory, humble CEOs may have different personal selection procedures that affect the composition of the TMT, which ultimately affects organizational performance.

Our review also suggests that we see main challenges in the literature deriving a consistent working definition of humility that entails generally accepted sub-dimensions. For instance, the number of dimensions ranges from five (Tangney 2002) to 13 different dimensions (Vera and Rodriguez-Lopez 2004). We discuss across the review which dimensions we see as overlapping. However, we urge future research to be detailed about the origins and definitions of the CEO humility construct in order to have a generally accepted conceptualization of the construct including subdimensions. Consistent definitions and explicitly stated conceptualizations will help the field to further grow and to enable cumulative insights.

Our review also suggests that we find a plethora of methods and scales in the general literature on Social Psychology but more homogenous methods and scales in the analyzed literature in Management outlets. These inconsistencies may also indicate that there is now very little interaction between Management researchers and Social Psychologists necessary to move a complex and multidimensional construct forward. For instance, humility scales (Davis et al. 2010; McElroy-Heltzel et al. 2017) in Social Psychology rarely find application in Management research, thereby inhibiting cumulative evidence on humility constructs. Future research can benefit from both approaches by accepting the beliefs and foci of Management research (e.g., focusing on the firm as a primary level of analysis; recognizing that firms differ; recognizing intermediary outcomes such as innovativeness, legitimacy, reputation, or status; and focussing on practical application) as proposed by Durand et al. (2017). At the same time, we should focus on further incorporating beliefs, foci, and methods from Social Psychology research. For instance, several studies do not report clearly on convergent, predictive, or discriminant validity, methodological standards in Social Psychology. Therefore, a greater focus on validity concerns and other method forms in the future (e.g., laboratory tasks or field experiments) may contribute to bridging the gap between Social Psychological and Management approaches to humility. For instance, “Appendix” Table 5 suggests that no article employed behavioral recording or nominal groups whereas just one article conducts an experimental approach, thereby providing several avenues for future research.

Our review leaves us more optimistic about the distinctiveness of CEO humility to other constructs. For instance, as we have shown before, Social Psychology literature tends to treat humility and narcissism as reversed scales and, therefore, as interrelated constructs. In contrast, our analyzed literature provides evidence that both constructs are only weakly correlated, thereby indicating distinct constructs on an individual level. In other words, the first results on CEO humility and its effect on CEO narcissism (Zhang et al., 2017) reject previous thoughts that both constructs are two ends of a continuum (see for a discussion: Tangney 2000). We urge future research to overcome the debate whether humility is “worth” to be treated as a distinct construct. However, incorporating control variables remains important at the same time. Future research should have the self-confidence to treat CEO humility as a distinct construct while simultaneously signaling knowledge about related constructs. If it is not feasible due to resource or data restrictions to empirically test related variables, we at least urge future research to provide face-validity that can be achieved with a very low number of cases. For instance, 10% of the studied articles employ a sub-sample analysis (“Appendix” Table 2) whereas 35% employ exploratory result verification procedures (“Appendix” Table 2), thereby providing opportunities to combine several procedures in order to increase research design sophistication. Future studies may also benefit from an established common baseline model of humility with constant controls. As discussed before, we used Tangney’s (2002) initial definition of self-esteem, narcissism and modesty as commonly related constructs to humility. Future studies should include these baseline control variables as well as controls such as core self-evaluation, openness to experience and the common performance predictors of self-efficacy, conscientiousness, and general mental ability as in Owens et al. (2013). We believe this would enable a common ground for empirical testing of the model and therefore bridge the gap between Social Psychology and Management research. More precisely, such base-line controls for future studies may be Honesty-Humility, learning goal orientation, Big-Five (FFM), modesty, narcissism, and core self-evaluations.

Another interesting finding of our review is the lack of findings regarding humility and demographics. As described earlier, Social Psychology research tends to treat humility as an outcome of an endogenous process (e.g., child socialization), but our review finds limited evidence that CEO humility is related to the age, gender, or educational background of the CEO, indicating that humility is a time-stable characteristic; although one should also note that CEO samples tend to be more homogenous than other samples, thereby reducing the variance of variables. Future studies may have a particular focus on demographic variables and check whether the effect of demographics becomes more prevalent if the method or the design (e.g., time-frame) is changed. In addition, these results open-up the possibility for humility trainings in future research. Future research on CEO humility could design trainings which affect one or several dimensions of CEO humility. An intervention study with groups that received humility training and groups that received no humility training would be ideal to test the effect of a training. We also encourage organizations to use human resource practices to detect leader humility but also actively develop and train leader humility in top executives. For instance, the voluminous literature on CEO succession (e.g., Balsmeier et al. 2013) may start to acknowledge CEO humility as an important determinant of the succession search for executives.