Abstract

The present study investigates how family firms respond to disruptive industry changes. We aim to investigate which factors prevent or support family firms’ adoption of disruptive innovations in their industry and which mechanisms lead to more or less successful coping with disruptive change. Our analysis is based on 24 qualitative interviews with top executives and on secondary data from an industry in which disruptive innovations dramatically changed the way business was generated. The industry in question is the mail order industry, which, in its early days, disrupted the retail business. When the Internet and, with it, ecommerce started to disrupt the industry in the late 1990s, the industry was characterized by a high proportion of family firms and a low level of innovativeness. While incumbent firms had been very successful for decades, most of them were confronted with serious turbulence when new entrants started changing the face of the industry. Our findings show that different factors impact reactions to disruptive industry change in two different phases, namely, opportunity recognition and opportunity implementation. While some of the influencing factors are determined by industry factors, family influence may function for better or worse for incumbent firms. Specifically, we find that in firms with a family disruptor, a family member in a powerful position who drives the adoption of the new technology, hindrances can be overcome and firms tend to show more successful strategies when reacting to the disruptive industry change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Disruptive developments within industries pose threats to incumbent firms (Christensen and Raynor 2003). Examples of industries that have been turned upside down by disruptive innovations range from film photography (Tripsas and Gavetti 2000), newspaper and book publishing (Gilbert 2005; Kammerlander et al. 2018), and real estate (Dewald and Bowen 2010) to travel brokerages (Osiyevskyy and Dewald 2015a). More recently, digitalization has been discussed as the next global disruptive challenge for incumbent firms (Kraus et al. 2019). The average age of the big five US tech firms, for example, is 24 years, and new startups, so-called digital unicorns, are waiting in the wings. More than 450 of them have already reached market capitalizations of more than $1 bn (CB Insights 2020). How do incumbent firms address this new disruptive challenge? How do incumbent family firms, which constitute the majority of firms in many countries worldwide (e.g., Van den Berghe and Carchon 2003; Mandl 2008; Astrachan and Shanker 2003), manage to not be left behind? After several decades of market disruptions, these questions remain highly topical.

The term “disruptive innovation” embraces both technological and business model disruptions (Christensen and Raynor 2003) that transform existing markets, help to establish new markets, and thereby vivify economic growth (Marvel and Lumpkin 2007). Many research studies have investigated the determinants that lead to or impede disruptive innovations being addressed by incumbent firms. These studies adopt leadership-centered approaches and suggest that the manager’s personality (e.g., proactivity, Seibert et al. 2001; tolerance for ambiguity, Patterson 1999; openness to experience, George and Zhou 2001) as well as the composition and structure top management team (TMT) (e.g., occupational background diversity, Goodstein et al. 1994; network ties, Geletkanycz and Hambrick 1997; stock options, Sanders and Hambrick 2007 influence innovation activities. At the level of managerial levers (Crossan and Apaydin 2010), a firm’s goals and strategies (Nicholson et al. 1990), organizational culture and climate (Andersen and West 1998; West 1990), resource allocation (White 2002; O’Brien 2003), or organizational learning environment (Madjar et al. 2002; Crossan and Hulland 2002) have been shown to affect responses to disruptive innovation. Finally, business processes (Cooper et al. 2001; Bessant 2003) seem to play an important part in shaping innovation activities.

However, the study of the organizational characteristics related to disruptive innovation remains underdeveloped (Cabrales et al. 2008). Family firm research has therefore focused on the owner family’s influence on the firm as a particular contextual frame for disruptive innovation management. Although many conceptual and empirical papers have attempted to explain differences in family firms’ reactions to disruptive market challenges, we still know very little about the specific factors that push family firms in one direction or another (Hu and Hughes 2020). Specifically, a process perspective on which factors inhibit or foster reactions to disruptive innovation throughout the different phases of the process (i.e., opportunity recognition versus opportunity implementation) has been largely neglected. Given the prominent role of managerial and organizational cognition in these processes, a better understanding of their impact is needed that takes into account the heterogeneity of owner families and their respective family firms (Calabrò et al. 2019; Hu and Hughes 2020). Based on these gaps in the literature, we pose the following research questions: Why do some family firms respond faster and more successfully to disruptive changes in their respective industry than others? How can family firms overcome industry- and firm-specific obstacles throughout the process?

Because this paper addresses “why” and “how” questions, the case study methodology was considered an appropriate research strategy. The mail order industry, in which disruptive innovations took place in the 1990s, was selected as the industry setting. The core business model of the industry was once a disruptive innovation itself: catalogue retailing (hereafter referred to as the mail order industry) (Christensen and Tedlow 2000). In its early days, ordering goods by mail was highly innovative and posed threats to established retail businesses. At the time online sales emerged, firms in the traditional mail order industry had decades of experience in logistics, purchasing, and marketing. Therefore, on the one hand, it would be reasonable to expect that with the emergence of the Internet, these firms should have had a head start over new market entrants and should have grown their businesses and remained market leaders. On the other hand, Christensen’s (1997) theory of disruptive innovation predicted the downfall of traditional mail order firms.

The present study more closely examines how incumbent firms, which were most often family owned and family led, coped with these changes and identifies factors that affected the more or less successful coping with this disruptive technology. Twenty-four interviews with top managers and owners of 9 German mail order firms who were in office during the disruptive changes in the 1990s were conducted, transcribed, and structurally analyzed, supplemented by secondary data. Based on this analysis, we develop a process model of how family firms react more or less successfully to disruptive industry changes and specifically focus on the differentiations of the two phases of opportunity recognition and opportunity implementation.

The present study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, it responds to calls from the wider innovation literature to more closely take multilevel phenomena into account when researching innovation (Crossan and Apaydin 2010; Felin and Foss 2006). While resource-based view models, for example, are applied at the organizational level, psychological theories are typically applied only at the individual level. Our model links managerial cognition with factors at the organizational level (i.e., the owner family, structures and hierarchies, resources) and thus provides a more comprehensive explanation for why some firms react more proactively to market disruption than others. It therefore also adds to the micro-foundational movement in management research in general and family business management in particular (De Massis and Foss 2018). Furthermore, our study emphasizes the specific influence of managerial cognition, which is a key constitutional part of upper echelon theory (Hambrick and Mason 1984). Under the condition of high discretion, which is especially the case for owner family managers, executives’ characteristics (and executive cognition) are correlated with strategy and performance (Finkelstein and Hambrick 1990; Crossland and Hambrick 2007). Our study sheds more light on the nature and strength of these relationships.

Second, by applying our study to the family firm context, an area that provides unique characteristics and dynamics in regard to innovation-related decisions (e.g., De Massis et al. 2013; Duran et al. 2016), we also add to the literature on family firm innovation. In doing so, we follow recent calls to investigate how family-related factors can be drivers of innovation (see Chrisman et al. 2015b; Ingram et al. 2016) and, more specifically, which family properties encourage the utilization of disruptive innovation as opposed to more conservative courses of action (Hu and Hughes 2020). This is in line with the call for a more nuanced view of the distinct challenges of family firms across different types of innovation (De Massis et al. 2015; Calabrò et al. 2019). Family firms are, in addition to pure financial considerations, particularly interested in enhancing their socioemotional wealth (SEW) (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007), which might be affected more strongly by disruptive than sustaining innovations. This study extends research investigating the effect of executives’ behavior on firm outcomes (Ling et al. 2008) and research on the family firm-specific characteristics that influence important family firm outcomes, thus clarifying the influence of executives (Ling and Kellermanns 2010; Minichilli et al. 2010). Specific characteristics of family firms, such as family image (i.e., the perception of being a family firm by external stakeholders) and family identity (i.e., the perception of being a family firm by internal stakeholders), are empirically shown to influence how family firms address disruptive innovations, which is in line with the expectations of Kammerlander et al. (2018) or König et al. (2013). The findings add to the view that family firms are a heterogeneous group (Chrisman et al. 2005; Westhead and Howorth 2007) and highlight specific differences that affect their innovativeness (De Massis et al. 2013).

2 Background

2.1 Disruptive innovation

Innovation is an important factor in the development of firms and their improved competitive advantage (Kraśnicka et al. 2018). In particular, disruptive innovationsFootnote 1 are an essential factor for the growth and success of firms and, beyond that, national economies (Büschgens et al. 2013; Tellis et al. 2009). Disruptive innovations transform existing markets, help to establish new markets, and thereby vivify economic growth (Marvel and Lumpkin 2007). Firms that develop disruptive innovations tend to dominate markets and increase their international competitiveness (Atuahene-Gima 2005).

Initial studies of disruptive innovations concentrated on discontinuous technological innovations (Christensen and Bower 1996; Christensen 1997). However, the economic value of any innovation can only come to fruition through commercialization via a business model (Chesbrough 2010). A firm’s business model describes the transaction relations with all its stakeholders, including the value proposition for each (Zott and Amit 2008; Zott et al. 2011). These transactions are based on a firm’s unique resource base and aim to generate value for the firm (DaSilva and Trkman 2014). From a more functional viewpoint, business models can be seen as a meta-routine for creating and appropriating economic value (e.g., Osiyevskyy and Zargarzadeh 2015; Zott et al. 2011; Zott and Amit 2008; Chesbrough 2007).

Hence, the notion of disruptive innovation must be broadened to embrace new business models along with new technologies, products, services, or R&D processes (Chesbrough 2007). Christensen and Raynor (2003) therefore extended the concept of disruptive innovation to include disruptive business models, uniting both technological and business model disruptions under the umbrella term “disruptive innovation” (Christensen and Raynor 2003).

More recently, disruptions have been acknowledged as a process of the “evolution of [the disruptive] product or service over time” (Christensen et al. 2015, p. 6) rather than an outcome, introducing a temporal facet to the discussion. There are many proposed process models for innovation in the literature (e.g., Frankenberger et al. 2013), which, in its simplest form, can be reduced to the two steps of exploring and exploiting (Schneider and Spieth 2013). Strategic entrepreneurship emphasizes the need to detect and recognize (i.e., explore) early opportunities and related challenges (Ireland and Webb 2007, 2009; Ketchen et al. 2007). Subsequently, in the exploitation phase, firms need to address challenges in terms of resistance to new routines (Holcomb et al. 2009; Ireland and Webb 2007), to respond to changing sources of value creation by reconfiguring their established ways of doing business (Amit and Zott 2010; Alvarez and Busenitz 2001) and to reallocate existing resources to help the new business grow (O’Reilly and Binns 2019). Thus, opportunity recognition (i.e., exploration) and implementation (i.e., exploitation) are conceptually different given the evolutionary phase of disruption.

Why some firms are more willing and able to recognize emerging disruptions and respond to them than others is of central interest in the academic literature. There have been different explanations, including the economic dilemmas incumbents face such as cannibalization of existing revenue streams (Christensen 1997), cognitive biases such as threatened mental models or identities (Benner and Tripsas 2012; Kaplan and Tripsas 2008; Tripsas and Gavetti 2000), behavioral aspects such as being trapped by core rigidities and organizational myopia (Danneels 2011; Leonard-Barton 1992; Levinthal and March 1993), and traits such as the innovation orientation and risk propensity of top management members (Kraiczy et al. 2015).

Opportunity recognition and the development of new organizational capabilities in response to disruptive changes is, to a large extent, driven by managerial cognition (Tripsas and Gavetti 2000). Researchers contend that executives of incumbent firms act with a fixed mindset, are unable to conceive of the opportunity offered by disruptive innovation and, hence, tend to display strong resistance (e.g., Christensen 1997; Gilbert 2005). The nascent disruptive business model might contradict managerial beliefs about success factors in the industry (Tripsas and Gavetti 2000), resulting in strong opposition from executives. Similar arguments have been developed in the business model innovation literature (Amit and Zott 2010), demonstrating that conflicts between the key aspects of established and new business models (novelty, lock-in, complementarities, and efficiency) can hamper opportunity recognition. Others note potential cognitive conflicts between traditional and new business models (Chesbrough 2010; Gilbert 2005), which are dispositional in nature and act as filters to select only the information related to the firm’s dominant logic (Bettis and Prahalad 1995). Hence, when analyzing the determinants of incumbent behavior in response to emerging disruptive innovation, managerial cognition and decision making should play a major role (Tripsas and Gavetti 2000; Benner and Tripsas 2012).

In addition to the firm’s executives, the success of disruptive innovations requires multiple facilitators both outside and inside the firm (Yang et al. 2014), who may hold informal or formal innovation positions. For example, innovation managers fulfil the role of the relationship and process promotor or a combination of both with the champion (Maier and Brem 2018). Various authors have proposed theories about the facilitators or promoters of this type of innovation (Howell and Higgins 1990; Howell et al. 2005).

Leadership and facilitation do not occur in a vacuum and need to be analyzed in the organizational context in which they take place (Porter and McLaughlin 2006; Dinh et al. 2014). Managerial levers such as a firm’s organizational structure (Damanpour and Gopalakrishnan 1998), learning environment (Aragón-Correa et al. 2007), culture (Tellis et al. 2009), resource base (Keupp and Gassmann 2013), or climate (Liu et al. 2017) have been shown to influence the recognition and implementation of disruptive innovation (for an overview of the literature, see Crossan and Apaydin 2010). Recently, researchers of the disruption phenomenon have devoted particular attention to the situational determinants of established firms’ responses to ongoing disruptive innovation—namely, the opportunity- or threat-related framing of disruptive business model innovation in the minds of managers of incumbent companies (Osiyevskyy and Dewald 2015b; Dewald and Bowen 2010; Gilbert 2005).

2.2 Disruptive innovation and the family firm

It is generally accepted that family involvement in ownership, management, and governance affects family firm innovation (Carnes and Ireland 2013; Chrisman et al. 2015b). However, research findings on the family-specific antecedents that affect innovation inputs, processes, and outcomes (Carnes and Ireland 2013; König et al. 2013) are inconsistent, especially in relation to innovation outputs (Urbinati et al. 2017).

Review articles and meta-analyses (e.g., Calabrò et al. 2019; Duran et al. 2016; Röd 2016; De Massis et al. 2013) have diligently itemized the different success and hindering factors for adopting innovation in family firms and have engaged in drafting a more comprehensive and conceptually structured picture of the research field. These reviews show that family firms possess specific qualities that have a positive influence on the reaction to innovation while at the same time they show characteristics that are detrimental to innovation. Negative aspects that constrain family firm innovation might include their conservative posture (Habbershon et al. 2003), organizational rigidity (de Vries 1993), risk aversion (Morris 1998), willingness to maintain control of the firm (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007) and limited propensity to use investment capital to fund innovation projects (Block et al. 2013). On the positive side, because utilizing disruptive innovations is inherently financially unattractive, at least in the short term (Kammerlander et al. 2018), the typical long-term orientation and involvement of multiple generations in the firm foster innovation adoption (e.g., Craig and Dibrell 2006; Llach and Nordquist 2010; Zahra et al. 2004). In addition, family culture and familiness are acknowledged as possible sources of competitive advantage for innovation since these resources are difficult to duplicate (Zahra et al. 2004), creating a climate of trust and shared goals (Dibrell and Moeller 2011).

Integrating different innovation levels (i.e., sustaining or disruptive) blurs the picture even more and adds to the already existing complexity and ambivalence of family influence on family firm innovation. A recurring finding in the wider family firm innovation literature is that family firms innovate incrementally rather than radically (Calabrò et al. 2019; Nieto et al. 2015; Roessl et al. 2010) and have less incentive to pursue disruptive innovations (Gast et al. 2018; Kraus et al. 2018). It is suggested that this is because family firms tend to focus on SEW preservation (Filser et al. 2018), avoid risk-taking to protect wealth (De Massis et al. 2014), have poorly developed innovation capabilities (Sciascia et al. 2015), and exhibit family entrenchment (Anderson and Reeb 2003) and family orientation lock (Herrero and Hughes 2019).

From a family firm resource view (Sirmon and Hitt 2003; Uhlaner et al. 2013), it is argued that under conditions of limited financial resources, family firms will focus on innovation strategies with a short-term return horizon instead of disruptive innovation strategies that require a long-term return horizon (Sharma and Salvato 2011; Singh and Gaur 2013). Furthermore, family firms possess the social capital to react quickly to innovation opportunities and to tolerate a degree of risk in doing so, which creates an advantage for disruptive innovation activities (Mani and Lakhal 2015; Zahra 2003). However, other studies have found that family social capital might also cause a limited perspective that prevents new resources and novel information, which are essential for adopting disruptive innovations, from entering the family firm (Herrero and Hughes 2019).

The ability and willingness paradox suggests that the availability of resources affects the ability of a family firm to respond to innovations (De Massis et al. 2014). The most frequently discussed resource constraints relate to financial resources, human resources, social capital, and firms’ knowledge and experience, which allow family firms to pursue the strategic direction in question (De Massis et al. 2014; Cucculelli et al. 2016). While ability positively influences disruptive innovation in family firms, the willingness to do so is also of great importance (Chrisman et al. 2015a). Owner families’ willingness to respond to market disruptions has been shown to be especially influenced by SEW considerations, ranging from the two extremes of acting conservatively and creating a risk-averse organizational decision-making culture (Miller et al. 2015) to starting to acquire resources to innovate (Brinkerink and Bammens 2018; Cucculelli et al. 2016) and pursing disruptive innovation. Furthermore, incumbents might be willing to respond to disruptive challenges but are affected by cognitive mechanisms and shared cognitive schemes that are inherently inadequate for making sense of disruptive innovation (Weick 2001; Kaplan 2011). In this context, a recent study proposed that organizational identity drives responses to disruptive innovations (Kammerlander et al. 2018). Specifically, the combination of both domain- and role-identity driven interpretations of disruptive developments leads to faster responses and more comprehensive adoptions of disruptive innovations (Kammerlander et al. 2018).

Besides resource based arguments and ability/willingness considerations, the SEW perspective has gained momentum in explaining innovation behavior of family firms. In short, family firms are described as organization with inseparable ties between an owner family and the firm (Dyer and Whetten 2006). They value affective utilities beyond financial objectives (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). Those affective utilities come in different forms, including the ability to exercise family influence, preservation of family reputation and dynasty, and the satisfaction of needs for belonging, affect, and intimacy (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007). In an attempt to structure the different affective needs of family firms Berrone et al. (2012) proposed a five dimensional framework (FIBER model). According to this, owner families strive to protect family control and influence over the firm (F), identify with the firm, for example with the firms traditions (I), have binding social ties with their stakeholders, like customers or suppliers (B), are emotionally attached to the business (E) and are bond to the firm through a dynastic succession intention in the sense that they want to handing business over from one generation to the next, keeping family heritage and tradition in the longer-term (R). This so-called socioemotional wealth is what gives family firms their distinctiveness and frames their decision-making processes. First studies argue that family firms in their focus on SEW preservation protect their family legacy and avoid pursuing disruptive innovations that have a strong tendency to harm such a legacy (De Massis et al. 2016). On the other hand, family firms can sometimes engage in disruptive innovation to gain long-term benefits without losing family control (Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2005). More recently, SEW has been suggested to play a moderating role on the influence of a family firm’s resources and innovation (Weimann et al. 2020). However, the specific factors that drive SEW in one direction or another remain an open question in the literature (Veider and Matzler 2016).

In summary, although a plethora of studies and insights into the peculiarities of innovation management in family firms exist, important gaps remain. Notably, scholars should more explicitly take into account the heterogeneity of innovation when investigating family firm innovation (De Massis et al. 2015) and should scrutinize the different family firm-specific factors that influence their reaction to disruptive versus sustaining innovation (Calabrò et al. 2019). This is important because disruptive innovation is substantially different from incremental innovation (Bouncken et al. 2018; Dewar and Dutton 1986). In this context, it is fruitful to delve deeper into the cognitions of the owner-manager because of her/his peculiar managerial power due to the more unified governance structures in family firms (Chen and Hsu 2009; Zahra 2005). These managerial cognitions have been largely ignored in research on reactions to market disruptions in family firms. Moreover, existing research has paid little attention to the temporal evolution of innovation (Gagné et al. 2014; Sharma et al. 2014). Thus, it is important to differentiate the determinants of innovation in family firms, at least between the opportunity recognition and opportunity implementation phases. Finally, although intensively discussed in the wider innovation literature (e.g., Howell et al. 2005; Markham and Aiman-Smith 2001; Tushman and Katz 1980), the role of facilitators should be explored more precisely (Calabrò et al. 2019) because facilitators may be a crucial element in explaining the heterogeneity of reactions to the innovation paradox (Chrisman et al. 2015a).

3 Method

Case studies are empirical inquiries that investigate a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, particularly when the boundaries between the phenomenon and the context are not clearly evident and appear in different forms (Yin 2014). Because this paper addresses “why” and “how” questions, the case study methodology was considered an appropriate research strategy.

3.1 Industry setting

As an industry setting for our multi-case study, we chose the German mail order industry. The mail order business once represented a disruptive innovation to the retail sector (Christensen 1997). Furthermore, the mail order business represents a form of retailing that has grown significantly due to e-commerce and has gained importance in the last few years. Broadly speaking, mail order retail can be defined as a method of buying products that are received by mail. The mail order business originated in the late 19th century. In the US, Aaron Montgomery Ward and his competitor Warren Sears published their first catalogues in 1872 and 1888, respectively (Britannica, britannica.com/biography/Montgomery-Ward, online; Sears, searsarchives.com, online). Examples of traditional mail order firms in the US include Sears Roebuck, J.C. Penney and Spiegel. In Europe, examples include La Redoute (France) and Littlewoods (Great Britain). We refer to firms that began as purely online players in the mail order industry as new entrants. Examples of new entrants are Amazon (US) and Alibaba (China).

What makes the mail order business a very interesting case for our investigation is that it was dominated by family firms, which were considered to have a conservative business approach (Habbershon et al. 2003). Furthermore, despite being confronted with the same industry challenges (i.e., the rise of the Internet and the establishment of new entrants such as Amazon) that made the industry setting homogeneous, there was considerable heterogeneity in the management of different mail order firms, ranging from owner-led companies to those with family-external management structures. Because we are especially interested in the impact of differing managerial cognition, this makes the industry a potentially fruitful field of exploration. Finally, the then-incumbent firms mastered the challenges posed by the Internet and the rising competition of new dominant market players differently. Currently, there are still some incumbents acting prosperously in the market, while others were pushed aside, left the industry, or ceased business.

3.2 Case selection

Researchers should apply a deliberate, theoretical sampling approach according to their research case (Eisenhardt 1989). Theoretical sampling can be understood by the way cases are chosen because they are particularly suitable for illuminating and extending relationships (Eisenhardt 1989). We focus our investigation on mail order companies in Germany. We define family firms following the definition of Chua et al. (1999). Top management in these firms may comprise members of the family, non-family managers or a board consisting of both groups. The firms differ with respect to how successfully they dealt with the emergence of the Internet (some even ceased to exist) and their product range (some are specialized, while others are universal mail order firms). Table 1 shows an overview of the cases included in the study. As we gained access to both more and less successful former incumbents in the mail order industry, we were fortunate to be able to base our analyses on a heterogeneous sample not only in terms of management structures but also in terms of the success in dealing with the disruptive industry change.

3.3 Data collection

As recommended by Eisenhardt (1989), we use different data sources to develop our case studies. By using different sources of data in the data analysis and different persons in the data collection process, the principle of triangulation is applied in the present study with the aim of increasing the validity of the results (Yin 2014). Additionally, the use of more investigators helps to build confidence in the findings and increases the likelihood of surprising findings (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007).

The Internet became relevant to the industry in the late 1990s, but it took decades for it to become part of the industry. We collected data on the history of the firms that were part of our sample and how they subsequently coped with the rise of ecommerce, but we focused the data collection efforts on the years between 1990 and 2000. The time span of interest centers around when Amazon began its official online shop and an increasing number of e-commerce firms entered the market. We collected secondary data based on documents from this time period and identified managers and family members who had prominent roles in the firms at that time. The interviews were conducted in 2014 and 2015. Sources for secondary data included public websites and radio and YouTube interviews as well as material that was distributed by the interviewed firms themselves. The collected secondary data comprised annual reports, firm publications, internal minutes and statistics, and online and offline interviews often published as newspaper articles. We systematically searched for newspaper articles and similar documents by searching the database LexisNexis. To be included in our analysis, articles had to focus on ecommerce-related topics. Additional documents were obtained from the interview partners (IP). An overview of the secondary data is provided in Table 1.

We conducted interviews with 24 representatives of 9 different firms and with industry experts who worked for different companies or had important positions in professional alliances within the industry. The interviewed persons were active members of their companies’ TMTs and decision-makers at the time the Internet and e-commerce emerged. All interviewees approved the recording of the interviews. The interviews lasted between 58 and 130 min and were transcribed immediately after being conducted. Some of the insights were discussed with the interviewees during the data evaluation period. All nine of the German firms selected were long-term members of the traditional mail industry; four firms were among the 10 leading mail order firms for many years, representing a total sales volume of €19.98 billion in 1996 (without affiliated firms).

All IPs were assured that all their statements and provided information would be treated confidentially. Because the industry is rather small and anonymity was guaranteed, only a very brief description of the companies is provided in Table 1. Most of the interviews were conducted by one of the authors. To improve the quality of the interview data, some of the interviews were conducted by two of the authors. To further increase validity, multiple executives of the majority of the selected firms were interviewed. It seems unlikely that these varied interviewees would engage in convergent retrospective sense-making (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007).

The interview guideline contained questions related to the IPs’ and their firms’ first impressions and reactions to the Internet, the situation of the industry in general, how business was conducted in the firms and how decisions were made at that time. To test whether the interview guideline was suitable for the study and whether all questions were understood by the IPs, two pilot interviews were conducted. Because of the quality of these interviews, both interviews were included in the data analysis process. However, some questions were adapted for the remainder of the interviews to provide a high level of clarity for the questions. Overall, the interview questions proved to be suitable for the research objectives. Due to the confidential nature of the interviews and the very specific information contained, the original data cannot be made publicly available.

3.4 Data analysis

The qualitative data analysis software MAXQDA was used for data management and analysis. Structured content analysis was chosen to code the data systematically. During the data analysis process, some of the interpretations were iteratively evaluated and discussed with the interviewed executives and other peer group members from the industry or business consultants (Eisenhardt 1989). As a starting point for data analysis, the analysis of each case (within-case analysis) as a stand-alone unit is recommended to ensure that the researcher becomes familiar with each individual case and to “…allow the unique patterns of each case to emerge before investigators push to generalize patterns across cases” (Eisenhardt 1989, p. 539). After the within-case analysis, we aggregated the data across cases. The data analysis process began with a predefinition of a code system. A combination of deductive and inductive code development was applied. The code system was evaluated with research associates and tested against the first transcripts in a second step. We identified first-order codes, which were aggregated to second-order codes in the course of the process. Coding is a method of discovery (Miles et al. 2013); hence, in step three, the code system was enhanced and adjusted. From the coding material, three overarching themes emerged. The coding structure and the underlying codes are shown in Fig. 1.

4 Findings

In the following, we present our findings in relation to the three overarching themes we identified. We identified two crucial phases between the emergence of the disruptive technology (the Internet and with it the opportunity to move on to ecommerce) and the reactions of the incumbent firms. After initial uncertainty about how the new technology should be classified, increasingly clearer judgment developed among the incumbents over time. These changing perceptions were characterized by the traditional way of doing business; thus, the Internet was viewed as a different approach to ordering and catalogue substitution rather than a new business model. The first phase involves perceiving the new technology as opportunity (opportunity recognition), and the second phase involves implementing changes in the business that leverage the new technology (opportunity implementation). The phases are linked to the overarching themes of perception filters and entrepreneurial baggage. The third theme, which covers the different family firm-specific influences in the process, connects the phases.

4.1 Perception filters

We identified perception filters as an overarching theme in our data. Perception filters hinder incumbents from perceiving the new disruptive technology as an opportunity and acting accordingly. Specifically, we identified four perception filters in our analysis: adhering to rules of the game, prior success, innovation culture, and split focus. Almost all interviewees stated that they became aware of the Internet in the early/mid-1990s, just around the time the first online retailers began their businesses in the US. However, this awareness did not mean that the executives considered the Internet to be relevant for their firms at that time. Their sources for awareness of the Internet were very different, ranging from hearing about it from colleagues or through the specialized press to meetings in their home country and abroad. Others became aware of the Internet through their trips to the US. However, it appears that with a few exceptions, there was only a small degree of entrepreneurial alertness among executives in established mail order firms. Business was further characterized by a low degree of change and slow, constantly reoccurring catalogue cycles instead of rapid change and adaptation. The main catalogue was like a metronome determining the beat and, thus, the pace of the industry.

Rules of the game Our data show that the incumbents perceived rules about how to do business and acted based on these rules. From the beginning, the new entrants played according to their own—and different—set of rules. From the perspective of the incumbents, these rules were new. In addition to having the courage to resist the usual market practices, new entrants were, thanks to the capital available, in a position to redefine the rules of the market to their own advantage.

IP 23: Amazon wouldn’t adhere to anything.

IP 22: They introduced new facts to the whole industry.

IP 24: E-commerce is a business model that frequently follows completely different rules.

It is also interesting to note that some of the interviewees argued that closeness between traditional mail order and e-commerce was perceived, but that closeness did not exist in reality. This perception existed because in both business models, customers were served via distance selling by utilizing similar systems and processes such as logistics. As such, Internet selling was perceived simply as an extension of the existing business and therefore was to be managed by applying the same rules as those for the existing business.

IP 23: If you take a closer look, at marketing for example, then e-commerce is actually much more oriented toward retail than the mail order business. Why? Because the mail order business has completely different lead times, completely different periods of time in which selling prices are fixed by advertising material. You have to decide on a much longer range, you have to guarantee much longer delivery capabilities. In addition, behind all that lies a model for pricing and the supply chain, whereas in the retail sector and online, you can react by the hour. That is why it is and why it was wrong over the past years that people believed that e-commerce was a continuation of traditional mail order business. That is only correct to a certain extent, and in the end, the winners in e-commerce are not the traditional mail order firms because the difference is much greater in time-to-market, in pricing, in resources.

Prior success Figures and statements in annual reports reflected the successful economic situation and how the investigated companies assessed themselves (e.g., double-digit growth in sales from 1997 to 1999 at “Foxtrott”, double-digit growth in EBIT at “Elite” Group, + 21%). At the same time, some incumbents considered themselves market leaders. Thus, most executives gave top priority to securing their existing business. They were not willing to devote considerable financial or human resources and time and management attention to the emerging Internet “issue”.

IP 19: Here too, we did not have (…) these new competitors in focus and did not regard them as serious competition; on the contrary, we said we will leave them behind. If we put our foot down, we can overtake them.

“We were the best”: in this way, different company leaders characterized the self-esteem of traditional mail order businesses at the end of the 1990s. They were economically successful and associated this feeling with being correct in their choice of strategy, procedure and decisions. Their previous successes justified their strategies and business models.

IP 3: We earned a lot of money then.

IP 20: A lot of people earned good money and were sure and they didn’t believe in that thing with the Internet.

IP 15: The company grew fantastically via this mechanism. Well, basically, there wasn’t any pressure to justify a different kind of behavior than what one was already doing.

Innovation culture Overall, innovations in the industry were rare, and an innovative mentality did not substantially exist in the established mail order companies. The view that innovation had nothing to do with the business was even occasionally expressed. In many cases, innovations were understood as new trends in the product range.

IP 4: Well, the industry is a relatively old industry; therefore, the number of innovations is probably disproportionate to other companies, other industries.

IP 15: Yes, that is simply the question: Is it a major task for retailers to be innovative? And, if so, what does that mean?

The level of innovation of the industry was considered rather low and less developed. Although the mail order industry views itself as considerably more innovative than shop retailers, the mail order industry as such is viewed as less innovative overall.

IP 11: I can’t really think of any really big innovations in the mail order business.

IP 16: The mail order business is not really innovative. You see that my prognosis is not good for this patient.

Various reasons for the stated views were provided: there was doubt concerning whether generating innovation was a primary task of the mail order business at all; the degree of innovation is limited due to a lack of capital; and a traditional industry such as the mail order business has difficulty being innovative per se.

Some mentioned examples of innovation in the industry were topics such as the means of improving the costs of order entry and customer care, for instance, by setting up call centers, the introduction of an own-parcel service, improvements in logistics to reduce delivery times, collective ordering systems or payment by installments. Examples of innovative companies in the traditional mail order industry are Foxtrott, Bravo and Echo. These companies addressed the issue of the Internet at an early stage and operated their business models from the beginning as multichannel businesses or, as in the case of Foxtrott, were considered to have “better management practices” (IP 19).

By contrast, the assessment of a firm’s own innovation culture shows a differentiated picture. Some of the interviewees described their own stance toward and dealings with innovations as weak and defined their character as cautious and reactive.

IP 2: The basic attitude was very negative. Negative….well, the right expression is conservative.

IP 9: You let the others advance and look to see how that develops and then jump in at a later stage.

In other companies, the approach to innovation was characterized by a type of trial-and-error culture in which many things were tested and in which employees were explicitly encouraged “to make mistakes” to some extent. Moreover, passion and pleasure for new things were a driving force for a culture of enthusiasm for innovation.

IP 11: Think of new mistakes so that old mistakes don’t get repeated.

IP 24: (…)people in our company are driven by a passion for new ideas.

IP 15: (…) individual employees or those responsible were constantly asked to think about how to improve processes, how to achieve leaner management, how to accelerate things. That was a permanent task, and people also carried it out.

However, a positive climate for innovation existed in only a minority of the firms in the industry. Considering innovation to be simply “none of our business” characterized the way most companies treated innovation in general and the Internet and e-commerce specifically.

Split focus As already indicated, the executives of traditional companies ran predominantly successful businesses that occupied most of their attention. Numerous interviewees felt impaired and burdened by, on the one hand, having to focus on a good, assessable business and, on the other hand, having to devote time and attention to the new Internet phenomenon. There was a persistent conflict related to the allocation of resources. It was clear that the existing business should not be neglected; nevertheless, firms became aware at some point that it was necessary to assign both time and money to the Internet.

In addition to focusing on their daily business, incumbents were often occupied with other strategic topics that determined the focus of their management and the use of financial and human resources. These interests included, for example, the promotion of internationalization strategies, generational change and going public (Bravo), expanding logistic capacities (Delta, Bravo) or improving processes (Foxtrott, Hotel).

4.2 Entrepreneurial baggage

The second overarching theme we identified is the entrepreneurial baggage the incumbents carried. This factor was especially important when implementing the new possibilities of the Internet into the business model. Our data show that financial limitations, existing customers, and structures and hierarchies were important drivers of how the firms dealt with the change.

Financial limitations For the incumbent firms, setting up structures for the new ecommerce channel meant they had to make large investments. Several IPs stated that not only was the setup of these structures expensive, but at the same time, their existing businesses had to continue running and developing because it was not yet foreseeable whether e-commerce would truly be successful. Therefore, companies avoided taking excessive risks by allocating too many resources to a still-unknown business. The compensation incumbents had originally hoped for (i.e., substitution of expensive catalogues with comparably cheaper contact via the Internet) could not be realized within a short time frame. At the same time, additional costs were incurred by the companies for the establishment and operation of, for example, online platforms and further marketing costs. Consequently, on the cost side, the incumbents could not compete with the new market entrants.

The interviewed executives were aware and occasionally jealous of the generous capital endowment some of the new entrants enjoyed and benefited from. According to the opinion of many of those interviewed, the main reason why new entrants were able to grow so quickly was because they had easy access to capital via venture capital (VC) funding or stock market flotation. To some executives from traditional mail order firms, it appeared that apart from a good story and high growth rates, little was required in the early years of the Internet to attract and impress investors.

IP 16: … investors inflated start-ups and business founders too quickly and with too much hot air. Those people accepted too high valuations too quickly for firms that really just consisted of a few PowerPoint slides, a few computers and 5 clever guys.

In contrast to the established companies, whose investments had a payback time within a certain period, there seemed to be no time pressure as such for new entrants to show profits.

IP 10: Of course you have to invest—either in a brand you don’t have yet or, if you have a strong brand, in shifting to another business model or to another sales channel. But you have to invest. And in an expanding market, you can’t just turn around after a year saying, “Hey, I want my money back”.

IP 23: That’s obvious. There is not one [traditional] company that doesn’t have a clear, limited investment budget. And if you do make an investment, you want to see that it pays off. Some expect that to happen within one year, others expect three years – but sooner or later, they want to see that it pays off.

The newcomers were therefore able to finance their rapidly expanding growth with accordingly high capital resources and generous expectations of their investors in terms of payback times.

IP 5: (…) the real big difference is that this venture capital that was available to a large extent in the States was willing to support companies that were constantly having losses.

IP 9: Today, it is easy for these guys. Today they say, I need another 50 or 100 million. Then they grow their businesses by another 200 million. But growth without profits is not difficult at all; I tell you that I would be able to drive every business quickly if I had enough money.

Compared with many of the new entrants who were funded by VC or already had their stocks listed, access to capital was rather difficult for incumbents, and necessary large investments were not fully made. This limitation also made it easier for the newcomers to expand their businesses without facing any consequential resistance from the incumbents.

Structures and hierarchies The incumbent organizations showed that they were not well suited for timely reactions to market changes. It appeared difficult, particularly in the larger mail order companies, to discuss the phenomenon of the Internet and its effect on their own business model in detail or collaboratively. This difficulty was due to the organizational structures at the time, which were described as large and powerful.

IP 8: Foxtrott was always extremely over-organized. Not under-organized. And extreme over-organization will always – in my eyes – prevent significant changes triggered by new impulses.

The number of board members and supervisory board members alone occasionally amounted to as many as 30 people: 10 board members with clear responsibilities and 20 supervisory board members, half of whom were employee and union representatives. In addition, there were management levels such as directors, heads of divisions and departments. The need for coordination between the parties was correspondingly high. Important topics such as the Internet are usually discussed by the board and the supervisory board, particularly when there is an effect on the company’s own strategy or large investments are involved.

In some of the incumbent organizations, the size of the TMT was considerable and appears to have weakened the antennas for innovation signals by influencing the complexity of communication structures and lowering the potential receptivity of organizational members.

The structures in the traditional mail order companies were consistently described as “rigid” and “sluggish” and were often characterized by political fighting within and outside of the top management. Although some managers saw no point in promoting the Internet and new business opportunities, disputes continued between departments to gain control of these new areas. The struggle to assume responsibility for the Internet and e-commerce was often highly competitive.

IP 10: To begin with, there was always a lot of arguing. IT wanted to have the topic: “Hey, that’s a technical thing. It belongs to us”. Then marketing: “No, that’s marketing; it has to do with advertising. The Internet and new media belong to us!” Purchasing then said, “No, actually ….we have to promote our products, have to make decisions here about which products. So it belongs to purchasing”. They were all fighting for it. Sales said, “No, it is a sales tool. We have to win new customers with it”.

One main reason for the power struggle was the allocation of resources within the scope of budget planning. Moreover, the Internet was by no means always a popular subject. In some companies, it was considered a nuisance.

IP 17: It was, as already mentioned, not regarded positively by other sales channels. There was someone sticking their oar in. We were always seen as troublemakers… Huge discussions in the whole company, what is it good for and why stir up the whole company for a little bit of business? That makes no sense. They were really annoying.

However, another picture of a different type of company became noticeable (Bravo, Echo, and Delta) in which shareholders and top management were open to new things and personally advanced change in their companies.

IP 15: Our shareholder—he came back from a conference and told us, “Okay, the Internet is now on the agenda, and we want to set it up professionally”. At least that is how it was then at Bravo.

This form of change predominantly affected those companies in which the shareholders were not personally represented in management or on the board (e.g., Golf, India, and Alpha). There was a different behavior at those companies in which the shareholders placed the Internet on their personal agendas and pushed it forward (e.g., Bravo, Echo, and Delta). In the latter case, there was considerably more clarity and focus in terms of the Internet and e-commerce.

Overall, existing structures and hierarchies for most incumbents, particularly the big players, had a negative effect on their success in addressing the new topic of e-commerce and the Internet in general. However, two factors helped to decrease this barrier. First, smaller firms with fewer board members were able to react more quickly to changes in the environment. Second, and more importantly, at firms in which a powerful family member showed great interest in the new topic, internal resistance could be overruled.

Existing customers Incumbents considered their repeat customers to be key drivers of their business because acquiring new customers is perceived as expensive and associated with higher economic risks. For this reason, product ranges, ordering methods, types of payment and advertising material were optimized and fine-tuned by incumbents to suit each of their existing customer groups. In particular, so-called impulse chains were the result of year-long tests and experience, and even the smallest of changes often led to incalculable and significant declines in demand.

Changes within the impulse chain or the advertising material occurred incrementally and carefully to avoid risking a negative effect on economic performance. Compared to new entrants, however, one incumbent was slow and had to bear the additional costs of Internet marketing on top of existing marketing costs.

IP 5: This step-by-step restructuring is, of course, a process that happened over years and years, and that’s why some pure online players were quicker because they started online right away.

IP 9: One wouldn’t have survived without catalogues.

IP 3: You can’t just join the online pure players by putting the whole main catalogue subtly onto the Internet. What will you do with the rest of your customers? With those 70% who are not using the Internet?

Even if an incumbent was willing to run these economically huge risks and serve customers solely through the Internet, this approach would not have been successful due to the lack of Internet access because the majority of the incumbents’ customers were living in rural areas with limited or even unavailable technical infrastructure to access the Internet.

IP 2: Technical difficulties in the beginning, like sufficient bandwidth and other access details, were one of the reasons why we didn’t get the whole product range placed online quickly enough.

The traditional mail order business mostly had an older and very often female customer base.

IP 9: We had customers similar to those of other large mail order businesses who were, on average, aged between 50 and 60. And there was always the key question: Will such customers accept this kind of medium, and how will they use it? Also the question: Who even has a computer or laptop at home?

In fact, households equipped with personal computers or laptops remained rather rare, as did fast data connections and high-performance broadband networks. In 1998, fewer than half of European households were equipped with devices, and only a negligible percentage of households had access to the Internet. Only a few mail order traders had a younger customer base or a predominantly male customer base (e.g., Bravo and Echo) that was also strongly technically minded, as was the case for Bravo.

In the early days of the Internet, the lack of technical infrastructure and the presence of predominantly older customers who showed little enthusiasm for online shopping represented the general conditions under which traditional mail order businesses perceived the Internet. Their view was also influenced by the established and successful advertising and sales channels to which they were accustomed. It appears that incumbents were listening too much to their customers’ existing needs and therefore had developed a reactive customer orientation.

Some incumbents did experiment with electronic media and gained experience in the “pre-Internet era”. This experimentation, for example, included catalogues on CD-ROMs within the scope of the existing business. Experiments with interactive TV were also initiated but were soon discontinued because the technological prerequisites were too onerous and the approach was not accepted by customers.

IP 14: (…) to produce catalogues from the digital database, to produce CD-ROMs, to produce forms from CD-ROMs that allow digital ordering.

The Foxtrott mail order company was one of the first in 1994 to publish a part of its catalogue on CD-ROM. This kind of multimedia shopping world was successful: although the first circulation totaled 50,000, almost 400,000 CD-ROMs were issued in the Autumn/Winter season 1997/98.

Traditional mail order companies have existed for decades, and certain images of these companies were developed accordingly during this time, with a fair number of them becoming well-known brands. Some of the interviewees believed that a rapid and credible change of their existing image was unlikely and associated this option with high economic risks because it might scare off the existing customer base. Hence, they did not see themselves in a position to stretch their existing brands in such a way that existing customers would continue to identify with them while being able to appeal to new, modern target groups.

IP 10: The brands were like they were. Old fashioned. But they had an enormous advantage, an enormous charm: these brands enjoyed trust from the population.

IP 11: Well, there was a lot of talk at the time about TV sales channels. But that did not really take off due to technical unavailability, and we decided not to continue with it. We did try to experiment, but that did not really work.

4.3 Family influence

The third theme we identified in our data was the influence of the owner family in the family businesses. This influence was shown externally by the image as a family firm and internally by the identity as a family firm. Beyond these firm-level concepts, we identified what we refer to as family disrupters. These individuals played a prominent role in dealing with disruptive innovation.

Family firm image (external perception as family firm) Most of the incumbents had a very traditional image, which was also shown in their hiring processes.

IP 19: We weren’t attractive enough. That already started when you entered our building. “Golf” was a traditional company, that has to be said … first you walked past a line of ancestors, then past antlers, then a dead bear or something else … all the old trophies from the founder and his sons-in-law, and you entered a firm where tradition not only smiles at you but where you are actually part of it. That is not appealing to young people. As an employer, we were in no way as attractive as a pure e-commerce company. That’s the way it is. And our company’s location also plays a role.

Most IPs regarded the firms as not very attractive for young and technically skilled employees, which made it difficult to find the talent that was needed. As a new, young and modern industry sector, Internet companies had great appeal to young, performance-oriented and highly skilled employees, whereas the incumbents were viewed as a boring and old-fashioned industry.

IP 23: The more innovative employees are likely to join the new Internet companies and not the traditional mail order firms.

IP 11: These start-up firms, they have a lot of young talent who are on fire, who really want something, who approach the subject with a naïve impudence, and you don’t find these kinds of people in larger companies.

IP 5: There were the start-ups that began with a team of youngsters who were already IT and Internet savvy. They could start in this new world right away, while the process of changing our employees’ mindset was still going on.

The fact that new entrants, with their modern and young image, could acquire talented employees who were keen and highly skilled can be considered a competitive advantage. The traditional family firm image was also evident in the customer perception of the brands.

IP 15: I think that’s the problem of established mail order firms in general, that their brands convey a dusty image that isn’t very appealing to younger customers. You can try to look and act modern, but it doesn’t work with your existing brand.

Family firm identity (internal perception as family firm) The incumbent firms typically identified themselves as family businesses. For them, this meant, for example, that sticking to the printed catalogue also meant not to having to lay off employees, whose jobs would cease to exist without the catalogue. Overall, identity as an “honorable business man” was important for many of them, and this perception was linked to refusing behavior that was demonstrated by the new entrants.

IP 5: Of course, they have a completely different business model. It is not their business model to build up a fashion company that makes continuous profits. Their model is to have a fashion company that grows very quickly, becomes internationalized and then to sell it with a marked up price, either to a strategic investor or, if they missed out on this, if they pumped too much money into it, then by floating on the stock exchange. That is the business model.

Family disruptor All incumbent firms had to deal with what to make of the new opportunities and potential threats posed by the developments centering around ecommerce. The firms were very similar in regard to the point in time when they became aware of the new technology. The intensity with which the topic was pushed inside the company mainly depended on its advocates. We found that in most of the firms, some individuals pushed the process to move the business model toward online applications and testing and introducing ecommerce. How the firms reacted strongly depended on who pushed the topic. The majority of the family’s external board members stated that they were aware of the topic but did not regard it as a threat. Furthermore, to most of them, the topic was not attractive because there were no short- or midterm gains to be made from it. However, there were exceptions to this. One external manager stated,

IP 10: I would come in through the front door and present my ideas, and if they (the board members) would kick me out, I would come back in through the back door.

However, these endeavors were not very fruitful. In contrast, in cases where a family member pushed the topic, reactions were more open. In some of the younger firms within the sample, members of the first generation who were still running the firm decided that they “just had to do it” (Delta). In other incumbent firms, next-generation members pushed the topic, often confronted with irritated reactions by members of the board. In these cases, incumbent firms were better able to deal with industry changes (e.g., Foxtrott, Bravo).

5 Discussion

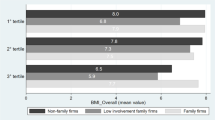

The findings of the present study provide deep insights into how incumbent firms coped with market disruption, in our case caused by the Internet and, therefore, e-commerce. Some incumbents had to cease operations. Most still exist, although they lost market share to new entrants. The inertia that is typically associated with the emergence of disruptive innovations is not inevitable (König et al. 2012). Our study supports this claim by showing that although the firms that were part of the multiple-case study were similar in many ways (all were family firms from the same industry and the same country), substantial differences existed in how they dealt with the new opportunities and risks posed by the disruptive developments. Based on our findings, we developed a process model of the different influencing factors during the two phases of opportunity recognition and opportunity implementation. The model is presented in Fig. 2. Based on our cross-case analysis, we found that the way the incumbent firms dealt with the changes and how successfully they implemented these changes in their business model differed. All of them were hindered at least to some extent by their perception filters and entrepreneurial baggage. While industry factors were stable for all of them and some of the influencing factors were less determined by being family firms, family influence played an important role at many points.

The findings show that there was not one factor that determined the reaction of the incumbents to disruptive developments in their industry; instead, it was a combination of diverse factors involving different levels of the incumbent firm that helped or hindered responses to emerging disruptive innovations. We thus contribute to a multilevel examination of responses to disruptive innovation (Crossan and Apaydin 2010; Felin and Foss 2006) by showing that perception filters, which exist at the individual level of the upper echelons (Hambrick and Mason 1984), can be detected within the opportunity recognition phase, while entrepreneurial baggage, as a firm-level factor, becomes more important in the opportunity implementation phase. Our findings considerably extend existing research on barriers to innovation, which have paid almost no attention to a temporal perspective (Gagné et al. 2014; Sharma et al. 2014). Because perception filters, and thus the upper echelons and their perception biases, play a pivotal role in the first phase of the innovation process, measures to overcome initial innovation barriers should focus on the individual and not on the organizational level. Not until the individual barriers are overcome, do firm-level barriers come into play. These should be addressed to facilitate the implementation of ideas, once an opportunity is recognized.

Some of the factors influence all incumbents in the same direction, while other factors are more specific to some firms than to others. While we found that the prior success of the business influenced the reactions of all interviewees in a similar way, consistent with the finding that judgmental overconfidence, which is strongly affected by prior success, constitutes an important decision-making bias (Hilary and Menzly 2006) and is negatively linked to innovation activities (Herz et al. 2014), the existing customer base differed. Most firms had a predominantly female, elderly customer base living in rural areas who did not have the technological equipment and knowhow to order online. In these cases, firms did not want to make changes that might exclude these customers. This is in line with SEW considerations suggesting that family firms establish emotional ties toward their stakeholders, which are, although sometimes financially detrimental, not abrogated (Cennamo et al. 2012; Romero and Ramírez 2017). Other incumbents had a younger customer base that was interested in technology, which helped them to try out innovative concepts – even though the performance of the new technology (e.g. catalogues on CD ROM) was not especially good or convenient. In these cases, no decision conflict arose because protecting their SEW (with regard to customer relations) did not collide with pursuing disruptive innovation. We add to calls for a more nuanced view of the challenges of family firms regarding disruptive innovation (Calabrò et al. 2019) by showing that distinct challenges apply to all family firms (e.g., prior success), while other challenges, such as existing customer bases, apply only to specific subgroups. Our finding challenges existing research on innovation in family firms, which predominantly focused on differences in innovation inputs, behavior, and outcomes to differences in family firm specific peculiarities like governance structure, SEW orientation, or resource configurations (e.g., Chrisman et al. 2015b) and comparisons with non-family firms. Our case study analysis suggests that determinants non-specific to family firm however varying between family firms, like the existing customer base, might also explain much of the differences between family firms.

A factor of particular importance in the context of responses to disruptive innovations in family firms is the family disruptor. In the early days of ecommerce, the necessary financial investments were very high, while the return was uncertain. The case analysis showed that a family disruptor is needed who drives the new topic and has formal as well as informal power to enable these investments and decisions. The importance of a family member involved in the top management of the company who pushes the new issue (in the present case, e-commerce) is in line with results from extant research (Duran et al. 2016; Röd 2016). Firms in which such a person was available were much more successful, and family firms could take full advantage of their familiness (Carnes and Ireland 2013).

With a view toward the general discussion of innovation management, it has been proposed, especially for disruptive innovations, that boundary spanners are needed to import external knowledge resources and customer demands and to exploit values created by external innovators and that traditionally discussed innovation champion and troika roles (Schon 1963; Witte 1973; Hauschildt and Kirchmann 2001) no longer suffice (Gemünden et al. 2007). The not-invented-here syndrome and group-think phenomena within the traditional troika may support adherence to the wrong innovation, which may be even worse than non-innovation. In this context, the family disruptor might fill this specific role and help to overcome these obstacles.

Our findings are also in line with the theoretical assumption of König et al. (2013) that once family firms have detected an innovation opportunity, they act more quickly and have more stamina. However, König et al.’s (2013) assumption that family firms take longer to recognize discontinuous innovation is not supported by our data. Our results rather suggest that the speed of opportunity recognition is attributed to individual perception filters of the upper echelons and, thus, might considerably vary within the family firm spectrum, depending on whether the top managers are more or less biased.

Another important finding is that although it is typically assumed that a lack of dependence on external capital is a competitive advantage of family firms (Arregle et al. 2007; König et al. 2013), the present results show that in such a rapidly changing environment, this financial independence can be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, if there is a family disruptor, financing decisions for new endeavors (for example, making part of the catalogue available online) are rather quick and uncomplicated. On the other hand, in situations in which competitors (new entrants) gain market share by “burning cash”, as was often the case in the early days of the Internet, family firms could hardly compete because, as some of our IPs stated, it conflicted with their understanding of doing business. These different rules of the game might be a reason why the industry as a whole has been overtaken by new entrants. The new entrants did not adhere to the traditional players’ shared understanding of how to do business.

Finally, our insights add to the explanations of why there are differences in family and non-family firms’ responses to disruptive innovations. We know little about the factors that enable incumbents to change their established mindsets and to respond more flexibly to a disruption by establishing new routines (Gerstner et al. 2013; Gilbert 2005; König et al. 2013; O’Reilly and Tushman 2004). We found that entrepreneurial baggage, which is rooted in the existing business (Coombs and Hull 1998), may have detrimental effects, especially for family firms. The competitive advantage of many incumbents in the mail order industry was rooted in the large efforts and expertise invested to produce the catalogues and operate a successful business. A large proportion of the specific knowledge needed for these processes lost its value because of the increasing importance of e-commerce. Whole departments of catalogue retailers are concerned only with the production of catalogues. One reason why the traditional mail order firms remained focused on their catalogue business longer than needed might be that as soon as the production of the catalogues stopped, the employees who specialized in these jobs would no longer be needed and would most likely have had to leave the company. Similar to the considerations of the existing customer base, a high SEW focus with a higher value of binding social ties and emotional attachment (Berrone et al. 2012; Cennamo et al. 2012) prevented incumbents from laying off these employees and modifying the firm’s internal competences by hiring new employees. This is in line with studies showing that family firms downsize less (Block 2010) and behave more socially responsibly toward their employees (Sanchez-Bueno et al. 2020).

5.1 Practical implications

Despite the unique situation of the mail order industry, general practical implications can be drawn from the results of the present study. First, decision makers must be aware that the perception of their organization of market signals is biased by perception filters (Benner and Tripsas 2012). Beyond the huge information load that decision makers already face, globalization further aggravates the situation, making it increasingly less likely that the “next big thing” will occur directly on one’s own doorstep (Van de Vrande et al. 2009). Decision makers therefore depend on reliable information channels that supply them with relevant information that is simultaneously as unbiased as possible (Hartman, Tower, and Sebora 1994; Nilakanta and Scamell 1990). External sources of information can be innovation agencies, conferences, and VC activities, and external networks in general can supplement information sources from inside the company. Second, companies should foster diversity in executive committees. Decision makers often have extensive experience and implicit knowledge, which is important and helpful but can also hinder the successful handling of new developments. Particularly in very homogeneous executive committees, the risk of missing or ignoring new impulses increases (Ling and Kellermanns 2010; Ling et al. 2015). The results of the present study indicate that (comparatively) young eccentrics often pushed the new topic of e-commerce (including at traditional mail order companies). A balanced mixture of experience and impartiality may help firms integrate new perspectives and make better decisions. Third, companies should aim for an innovation culture (Chandler, Keller, and Lyon 2000). The results of this study show that companies were more successful when they promoted a “trial and error” culture. The development of a company culture of this type can help to successfully address new challenges. New ideas should not be forced into existing structures. Although new ideas start on a small scale and with few financial resources, they still consume the attention and resources of management. Particularly in an environment with a clear focus on existing business and tough internal competition for budgets and responsibilities, new ideas often have little chance of succeeding. Separating new activities from old activities, for example, by establishing a spin-off, could be a step toward success (which some of the firms in the sample did successfully in the past years).

5.2 Limitations and future research

The present study has several limitations that present avenues for future research. First, the time span that was the center of interest of the interviews dates back more than 15 years. The respondents’ statements might be biased by sense-making and other cognitive delusions due to the retrospective nature of the interviews (Merkl-Davies et al. 2011). This methodological issue occurs in most qualitative studies using interviews (Cox and Hassard 2007). We attempted to minimize biases by conducting interviews with several IPs in most of the firms and supplementing the interviews with secondary data. Although it seems hardly feasible, future research could address this problem by beginning the case analysis at a very early stage of the emergence of a disruptive technology.