Abstract

In this study, using a unique hand-collected sample of 523 closely held Colombian family firms and 5.094 firm-year observations, with 4907 board members, including 833 female board members, we show that female directors have a negative effect on firm performance. However, when we separate female directors into two groups, family female directors and outside female directors, we find that the latter has a positive and significant effect on firm performance. We further construct a human capital index after a detailed analysis of 15% of the total curriculum vitae of directors for those in our sample we were able to find. Although the subsample is not representative enough to make general claims for the whole sample due to data constraints, we shed some light about a potential gender bias in the development of the human capital of heirs and the corresponding impact of different levels of directors’ education and experience on firms’ financial performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The empirical evidence that relates gender diversity to corporate financial performance is complex, and results are not consistent across different studies. A body of evidence supports a positive relationship between greater gender diversity on the board of directors and better financial performance (Carter et al. 2003; Erhardt et al. 2003; Campbell and Mínguez-Vera 2008; Dezsö and Ross 2012). Other studies find no statistical relationship between a higher proportion of female directors and performance (Shrader et al. 1997; Rose 2007; Gregory-Smith et al. 2014; Chapple and Humphrey 2014). Finally, some find a negative relationship between female involvement on boards and financial performance (e.g., Adams and Ferreira 2009).

This inconclusive evidence in the literature calls for further empirical enquiry. Wagana and Nzulwa (2016) argue that many of the results reported so far come from samples of listed firms in developed countries and that we know little about the effects of gender diversity in less developed countries. The main contribution of this paper is to improve our understanding of the impact of board diversity on firm financial performance, especially regarding the role of women in the context of closely held family firms in emerging countries.

Before controlling for family ties, our results are consistent with studies that find a negative relationship between gender diversity and financial performance (e.g., Adams and Ferreira 2009). However, to better understand the impact of female directors on firm performance, we divide those in our sample into two groups, family female directors and outside female directors. We show that having a greater proportion of female directors without ties to the family business enhances financial performance significantly, while the opposite holds for family female directors.

This positive effect of outside female directors on financial performance is consistent with empirical evidence showing that few women reach the top of the organizational ladder (e.g., Schmid and Urban 2017; Cook and Glass 2014; Holgersson 2013; Gregory 2009). One can expect that those who do succeed have above-average personal competence. A higher level of professional preparation should have a positive impact on the corporate board’s decision-making process, with the ultimate effect of improving financial performance. The negative effect of family female directors on financial performance is also consistent with the literature related to nepotism and dynastic management in family firms (Pérez-González 2006; Caselli and Gennaioli 2013).

In a second contribution to the current literature, we construct a human capital index to control for talent. However, family firms in Latin America in general, and in Colombia in particular, are characterized by a high level of opacity and we were able to find information for only about 15% of the curriculum vitae of directors in our total sample. Although the subsample is not representative enough to make general claims for the whole sample, in this smaller dataset outside female directors are significantly better trained than family female directors in terms of education and experience. Additionally, family female directors in this subsample are significantly less trained than family male directors, and family male directors are better trained than outside male directors. These results shed some light on a potential gender bias in the development of the human capital of heirs, suggesting that family firms favor men over women to take control of family businesses. This is consistent with patriarchal practices in family businesses (Mulholland 1996).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: We first review some of the relevant literature that serves to develop our hypotheses; we then describe our data and explain the methodology we employ; we subsequently present and discuss our results before concluding.

2 Literature review and hypotheses development

There is an international call to redesign the structure of corporate boards of directors to create more diversity and a more heterogeneous group of decision makers (Kumar and Zattoni 2016). According to Farrell and Hersch (2005) the number of women serving on corporate boards as directors increased substantially during the 1990s. They also show that women tend to serve on boards of firms with better performance. Moreover, Cook and Glass (2014) show that diversity in the decision process (and not necessarily performance) explains the likelihood of finding women in firms’ top leadership. However, some early puzzling evidence regarding gender diversity and financial performance shows that abnormal returns associated with announcements of the selection of a woman as a new board member are insignificantly different from zero (Farrell and Hersch 2005).

The literature identifies many hypotheses to explain a positive relationship between gender diversity on boards and financial performance. According to Adams and Ferreira (2009), female directors—in the context of agency theory—are more independent from the influence of managers relative to their male counterparts. Additionally, there is evidence that female directors, relative to male directors, are more likely to (1) participate in monitoring committees such as those concerned with auditing, nominating, or corporate governance, (2) recommend ousting the CEO after a poor stock price performance, and (3) routinely attend the board meetings. Note that in a previous study the same authors recognize that independence from managerial influence creates potential costs as well as benefits and show skepticism over a potential positive relationship between boards’ gender diversity and financial performance (Adams and Ferreira 2007).

Different authors argue that greater gender diversity should improve directors’ monitoring and advising roles as well as the quality of boards’ decisions because of important inherent differences between genders, which are considered more valuable in firms with complex operations (e.g., Hillman 2015; Anderson et al. 2011). If greater gender diversity implies less correlation among the information sets of board members, the different views among members will enhance a board’s decision-making process and have a positive effect on the firm’s expected financial performance (e.g., Arfken et al. 2004; Van der Walt et al. 2006). In addition, Dawson (1997) argues that women are inherently different from men in their ethical behavior.

The empirical evidence that relates gender diversity to corporate financial performance is mixed. Carter et al. (2003) show a positive and significant relationship between a higher proportion of female directors on the corporate board and firm value, proxied by Tobin’s Q, after controlling for size, industry, and other corporate governance variables. They analyze firms that comprise the Fortune 1000 index. Shrader et al. (1997) use different accounting ratios, such as return on sales, return on assets, return on investment, and return on equity, to measure financial performance and find that a greater proportion of women as middle managers impacts financial performance positively. However, when they consider the proportion of top female managers and the number of female board members, they do not find a statistically significant relationship between gender diversity and financial performance.

Some researchers like Carter et al. (2010), who analyze a sample of firms in the S&P 500 index during the period 1998–2002, find no statistical relationship between gender diversity and financial performance. Consistent with these results, Rose (2007) finds no relationship between gender diversity and performance after analyzing a sample of Danish firms. Triana et al. (2014) show results associated with a complex interaction, as follows. When a board faces no threat of low firm performance, gender diversity contributes positively to strategic change. However, when there is a threat of low performance, a more gender-diverse board negatively affects strategic change. In the UK, Gregory-Smith et al. (2014) find evidence of gender bias in the appointment of women as non-executive directors, but show that the presence of women on the board has no direct effect on company financial performance.

Dale-Olsen et al. (2013) study the effect that the 2003 quota reform for Norwegian boards has had on the financial performance of non-financial public limited companies and ordinary limited companies. They find no effect attributable to the regulatory imposition of a minimum proportion of female directors on Norwegian boards. However, Ahern and Dittmar (2012), using the same Norwegian case, found a significant drop in firm value and Tobin Q; they argue that pressure on firms to comply with the imposed quotas created much younger and less experienced boards.

Some international cross-country evidence supports a positive relationship between a higher proportion of women serving on corporate boards and financial performance. Terjesen et al. (2016) analyze a comprehensive sample of 3876 public firms in 47 countries and find that firms with more female directors have a higher return on assets (ROA) and Tobin’s Q. They also find that firms facing complex environments have more gender-balanced corporate boards. Analyzing a sample of 159 banks based in nine different countries, García-Meca et al. (2015) find that gender diversity increases bank performance. However, when the regulatory environment is weak and investors face low protection, the influence of board diversity on financial performance decreases. In the same vein, using a sample of 102 commercial banks based in ASEAN-5 countries, Ramly et al. (2017) show that independent women directors contribute significantly to the bank’s efficiency level. Post and Byron (2015) combine the results of more than 140 research papers and perform a meta-analysis to find that women on boards are associated with positive accounting returns but have no effect on market valuation.

Finally, some country studies support a positive relationship between gender diversity and performance. Vafaei et al. (2015) find that a higher proportion of female directors is associated with better financial performance in the top 500 listed firms in Australia during the period 2005–2010. After controlling for firm-specific variables, ownership and governance structure, and possible endogeneity, Gordini and Rancati (2017) analyze a sample of 918 public firms in Italy and find that gender diversity, measured by the proportion of female directors on the board and by the Blau and Shannon indexes, significantly increases Tobin’s Q. The analysis of the results depends on the context of Law 120/2011, which prescribes gender quotas (at least one-third of board seats must be held by directors of the less-represented gender). For a sample of Spanish firms, Campbell and Mínguez-Vera (2008) find a positive relationship between gender diversity, as measured by the percentage of women on the board and by the Blau and Shannon indices, and financial performance.

Most of the evidence in the literature is associated with studying the relationship between corporate board gender diversity and financial performance in the context of large public firms based in developed economies (Wagana and Nzulwa 2016). In one of the few studies using a sample of firms from an emerging country, Kılıç and Kuzey (2016) analyze the relationship between board gender diversity and firm performance in Turkey. As expected, they show that Turkey corporate boards are male-dominated, consistent with patriarchal practices (Mulholland 1996). However, they find that a greater level of gender diversity relates positively to financial performance. Liu et al. (2014) also find a significant positive relationship between gender diversity on the corporate board and firm performance in a sample of publicly listed companies in China.

In the context of Italian family firms, Bianco et al. (2015) distinguish between family-affiliated and non-family-affiliated female directors. They show that family-affiliated women are more common in smaller firms with concentrated ownership; conversely, non-affiliated women are more likely to serve in listed and bigger firms that have a greater fraction of independent directors. This approach is important because, in the context of family firms’ boards it is very common to find family directors (Sageder et al. 2016; Acero and Alcalde 2016) and family-affiliated women could be present for reasons other than the monitoring or advising role of a professional director (e.g., family quotas, nepotism, within-family agency conflicts reviewed by Villalonga et al. 2015). Pollak (1985) argues that poor performance of boards in family firms may be tolerated, given the difficulty of supervising and disciplining family members. One can also argue that sometimes family members are not suitable as directors because their talents may not match with family business activities.

As the previous review shows, the literature regarding board gender diversity is extensive and complex, given the contradictory results from the theoretical and empirical perspectives. In “Appendix 1” we present an overview of this literature that supports our discussion and our hypotheses development subsection that follows.

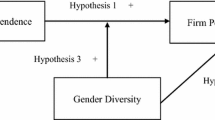

2.1 Hypotheses development

The dominance of males in a business context has been widely documented. For example, Sweden has a long tradition of gender equality in fields such as politics, public service, academia, and culture, but in business 87% of board seats and 84% of top management positions are held by men (Holgersson 2013). Some authors suggest an “old boys” network or homosociability (male preference for the company of other men in social settings) is also prevalent in the context of family firms and favors men as firm leaders (Gregory 2009; Holgersson 2013). Ibarra (1992) shows that men’s social networks are more male-centered than women’s networks, which are more heterogeneous.

The literature also recognizes gender bias regarding succession in family firms. Bennedsen et al. (2007) find that these firms are more likely to pass control to a firstborn male than to a firstborn female. Specifically, using a dataset of 5334 successions between 1994 and 2002 in limited liability firms in Denmark (publicly and privately held) these authors find that the frequency of family succession is 29.4% when the firstborn is female, which increases to 39% when the firstborn is male (a 32.7% increase). Moreover, Mulholland (1996) argues that patriarchal practices overshadow female kin and propel male kin to a position of power. Bertrand et al. (2008) show that founders’ sons are more likely to participate in the firm through direct ownership and as board directors, especially when the founder of the group is deceased. Mehrotra et al. (2013) discuss two unique practices of Japanese business families; namely, marriages arranged to inject talent into business families and adoption of promising male adults as principal heirs.

Due to the prevalence of men in businesses in general, and in the context of family firms in particular where gender bias is prevalent, we assume that the level of human capital of family male directors should be higher than that of family female directors. We expect family male directors to assume a leadership role early in their career (Bennedsen et al. 2007), and this early involvement in family business operations could produce valuable tacit knowledge for certain types of business (Bertrand and Schoar 2006). There is also evidence for a higher level of qualification and overall human capital for men in comparison to women when analyzing cohorts from the 1960s. Joshi et al. (2007) found that a bigger proportion of women had fewer qualifications and less experience compared to men in cohorts from 1958 and 1970 made up of individuals in their early thirties and employed full time. Moreover, they show that the older the cohort, the wider the difference in human capital.

In Colombia women began enrolling in higher education only in the early 1940s, gaining the right to vote in the 1950s. Considering these facts and taking into account the gender bias discussed above, we argue that a prevailing gender bias will negatively affect the family investment in human capital for female heirs as potential successors in a family business context. Therefore, we expect entrepreneurial families to invest more in male kin human capital and hence for family male directors to be better prepared than family female directors.

Hypothesis 1

Family female directors show lower levels of human capital than family male directors.

The financial impact of the appointment of heirs to boards or top management positions is controversial. Villalonga and Amit (2006) show a significant under-performance of family firms when heirs are appointed to key posts. Others have also reported a significant discount in firm value when heirs are appointed to top management positions (Smith and Amoako-Adu 1999; Pérez-González 2006). Additional country studies report similar negative responses to family-related appointments for the case of Italy (Cucculelli and Micucci 2008), Norway (Barth et al. 2005) and Denmark (Bennedsen et al. 2007).

However, these results are averages, and it is possible that a well-prepared heir could have a positive impact on firm performance after his/her appointment. For example, Pérez-González (2006) shows that family CEOs whose undergraduate universities were top-ranked were associated with higher operating returns and higher market-to-book ratios 3 years after taking over the firm. There is also empirical evidence discrediting any discount in value with heir CEOs. For example, in Western Europe (Barontini and Caprio 2006) and Germany (Andres 2008), there were no differences in performance in firms run by descendant CEOs. Moreover, Sraer and Thesmar (2007) find that French family firms run by heirs actually outperform those run by outside managers. In addition, tacit knowledge could be an advantage for heirs involved early in family business operations (Bertrand and Schoar 2006).

In this regard, human capital, and not gender alone, should be the source for any observable effect that family director presence has on a firm’s performance. Hence, we expect family female directors in general to be associated with poor firm financial performance while the opposite is expected for family male directors. Mazzola et al. (2008) suggest that heirs’ involvement in management facilitates their training and provides crucial tacit business knowledge and skills. However, the appropriation of tacit knowledge depends mostly on the family’s willingness to allow heirs to get involved in firm operations early in their careers, which, as argued above, is more probable for male kin due to gender bias.

In addition, the literature on family firms recognizes the existence of nepotism, especially in countries with weak institutions. Caselli and Gennaioli (2013) develop the concept of “dynastic management,” a non-meritocratic practice that implies the generational transmission of management in family firms. They argue that this dynastic management has an important negative impact on financial performance not only at the firm level but also at the country level. In the same vein, Pérez-González (2006) shows that the economic costs of nepotism are large and that minority shareholders are more likely to absorb those costs, given that they do not enjoy private benefits of control. Burkart et al. (2003) offer a theoretical explanation for this phenomenon, arguing that a less competent family manager counterbalances the cost of hiring an outside manager, which could increase expropriation risk in weak institutional environments.

If nepotism is a relevant driver motivating heirs’ involvement in family firms, together with the expected lower level of human capital for female kin due to the gender bias discussed above, we expect family female directors to have a negative impact on firm performance. Adams and Kirchmaier (2015) argue that even competent and talented women could experience negative discrimination due to cultural and market values regarding woman’s work. For example, men’s social networks are more male-centered (Ibarra 1992), potentially affecting women’s ability and opportunities to generate value for the firm by engaging in business relationships.

Studying a sample of closely held family firms based in an emerging country, we expect a negative (positive) impact of family female (male) directors on firm financial performance, explained on one hand by a potential gender bias regarding education and preparation for the succession process, consistent with patriarchal practices in family businesses (Mulholland 1996), and on the other hand by nepotism.

Hypothesis 2

The presence of family female (male) directors will be negatively (positively) correlated with firm financial performance.

We conjecture that differences in female directors’ performance come down to human capital, which is related to training and experience. As explained above, family female directors could be involved in their firms for many reasons other than their human capital. According to Pérez-González (2006), outside CEOs have more experience on average than family CEOs. Tavora (2012) argues that situational factors like cultural legacy and family dynamics explain the presence of women in family businesses. According to Bertrand and Schoar (2006), in preserving and building the family legacy through the firm, families could attempt to maintain control at all cost. Gómez-Mejía et al. (2007:106) use the term socioemotional wealth to refer to “non-financial aspects of the firm that meet the family’s affective needs, such as identity, the ability to exercise family influence, and the perpetuation of the family dynasty.”

This is not the case for outside female directors. They must pass through a much more stringent selection process as a result of discrimination in the workforce for top managerial positions (Schmid and Urban 2017) and the lack of family ties. Therefore, only above-average outside female directors will be appointed. Adams and Kirchmaier (2015) argue that the glass ceiling is not only attributable to a wage gap and fewer opportunities for advancement, but is also due to religion and cultural factors such as attitudes toward working women and woman’s work, among other influences. Gender discrimination implies that recruiters are more likely to choose men when confronted with two identical CVs, gender being the only difference (Steinpreis et al. 1999; Moss-Racusin et al. 2012, 2014; Holgersson 2013). That is, men have more access to job opportunities than women with an equal level of education. Hence, even outside female directors with high levels of competence and talent can be discriminated against in a number of other ways as well.

We argue that the glass-ceiling effect impacts outside female directors more compared to women with family ties. Therefore, reaching the top could imply above-average qualification and personal competence for this set of women directors.

Hypothesis 3

Outside female directors show higher levels of human capital than family female directors.

According to Bertrand and Schoar (2006), strong family ties can lead to nepotism, the hiring of key managers and directors from within the family rather than from a broader pool of more talented professionals. Hence, when studying the impact of female directors on firm performance, we have to differentiate between family female directors and outside female directors. As discussed above, the appointment of a female director under criteria other than meritocracy is more probable for female kin than for outside women in family firms. Moreover, this is even more probable when a weak legal environment leads families to prefer that relatives rather than outsiders manage their businesses, even if the outsiders have demonstrably more skills and preparation (Burkart et al. 2003).

Pérez-González (2006) argues that some firms promote CEOs on the basis of family ties rather than merit. His study offers empirical evidence showing a lower level of performance for firms under the managerial control of family CEOs in comparison to those with non-family CEOs. Although these findings consider only CEO positions, they could also apply to directors.

Outside female directors should have a positive impact on firm performance. Joshi et al. (2007) show that although pay still lags, women’s education and experience in the corporate world have increased substantially. Moreover, Schmid and Urban (2017) find that capital markets react negatively when a female board member suddenly leaves the firm, possibly because the market recognizes that women directors undergo a more rigorous selection process due to the glass-ceiling effect. Hence, they should have a positive impact on board decision-making and ultimately on firm performance.

For a sample of banks in the United States, Nguyen et al. (2015) show that although age, education, and prior work experience as executive directors with daily management responsibilities are associated with positive market performance, gender by itself has no effect on shareholder wealth. Therefore, we conjecture that outside female directors will show a positive association with firms’ financial performance.

Hypothesis 4

The presence of outside (family) female directors will be positively (negatively) correlated with firm financial performance.

Next, we empirically test these hypotheses using a sample composed mostly of closely held Colombian family firms.

3 Data and methodology

We hand-collected a unique dataset of closely held Colombian firms affiliated with business groups, a feature not commonly found in the empirical literature. We also gathered financial-related data as well as information on ownership composition and board design from two governmental agencies. The Financial Superintendence (SFIN) regulates and monitors public firms and the trading of their financial securities, while the Superintendence for Commercial Societies (SSOC) regulates non-financial institutions, monitoring events associated with corporate restructuring and bankruptcy procedures. SSOC maintains financial records for medium-sized and large privately owned firms. In some cases, notes to the financial statements include information about major shareholders, appointments to the board, and CEO-related information. We found additional information related to directorships and CEOs from the Chambers of Commerce, for those companies that are registered.

With 8640 records of firms in the SSOC and SFIN databases for the period 1996–2006, we then apply four filters. First, we eliminate 31 firms subject to special regulation; i.e., commercial banks, utilities, and former state-owned enterprises registered with the SFIN. Second, we exclude from the analysis 7325 firms that lack ownership details and sufficient information to identify either majority shareholders or pyramidal ownership structures. Our aim is to identify the ultimate owner of the firms under analysis. If we include firms without information about the ownership structure, we could mistakenly consider firms under family control through ownership as if they did not have family involvement. As a consequence, we could mistake some family directors as outside directors with no family ties. We could, therefore, create an identification bias without this restriction.

Finally, we impose two additional requirements for the remaining 1284 companies in the sample. First, companies must report complete ownership and board composition information for at least three consecutive years. Second, we include companies that are part of a business group only if they represent at least 50% of the total number of companies that form that business group. For example, if the total number of companies in the business group is 11, we need to gather information for at least six of the companies that form the business group. This filter allows us to build more accurate information regarding pyramidal control within the group and to identify the ownership structure with more precision and determine whether there is family control through pyramidal ownership. The first of these two requirements excludes 600 firms, while the second removes 161 firms.

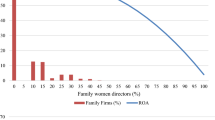

The total number of firms in our refined database is 523, while the number of business groups under analysis is 28. The final sample of firms represents approximately 40% of the population of entities that report financial information to the SSOC. The time-series analysis over the period 1996–2006 of this cross-section of Colombian firms generates a final unbalanced dataset of 5094 firm-year observations. Given that ownership-related variables are closed to public access by law for a period of time, it is not possible to get more up-to-date information.

We use adjusted return on assets (ROA) to measure financial performance for our sample of 523 closely held Colombian firms. We define adjusted ROA as the ratio of net firm income to total assets in excess of the average ROA for the same industry and year. We use different variables to proxy for gender diversity. First, we construct the variable percentage of female directors as the proportion of female directors on the corporate board. Additionally, we use dummies to measure the interaction between gender and other properties of the members of the board, specifically, family ties.

We include control variables belonging to two different categories. The first set of variables control for corporate governance structures and effectiveness in a family firm. In this category, we create three variables to control for the involvement of the founding family. Family CEO is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the CEO has the founding family last name, and zero otherwise. The variable family ownership is a dummy that takes the value of 1 if the family is the largest shareholder of the firm, and zero otherwise. Similarly, the variable indirect family control takes the value of 1 if the family holds control indirectly via pyramidal ownership structures, and zero otherwise. Second, we construct the variables CEO and board turnover to control for the effectiveness of the CEO and the board members in enhancing value through better financial performance. We also create a dummy to identify the affiliation of the company under analysis with a business group. The variable auditing firm takes the value of 1 if one of the main auditing firms in Colombia audits the firm’s financial reports, and zero otherwise. Finally, we use a contestability measure calculated as the voting stakes of the second- and third-largest blockholder relative to the largest voting block, a variable that seeks to capture the power balance of different shareholders (Maury and Pajuste 2005).

We design the second set of variables to control for firm-specific properties that affect the firm’s financial performance. We measure firm age and size by the number of years since the company’s incorporation and by total assets, respectively. Dividend ratio is the amount of cash dividend paid divided by total assets. Finally, we estimate the level of growth opportunities by calculating the percentage growth of fixed assets.

To test the level of human capital in our sample, we construct an index after examining the curriculum vitae (CVs) that we were able to find for around 15% of the 5815 executives in the sample (4907 corporate board members and 908 CEOs). According to Schultz (1961), human capital embodies the knowledge and skills people have that allows them to make good decisions and create wealth in the economic system. Hence, we proxy human capital by extracting executives’ characteristics through the analysis of their CVs.

Because of restrictions on information disclosure and the high level of opacity of Colombian firms, as mentioned before we were able to collect only 815 CVs of CEOs or directors, 698 from men (85.6%) and 117 from women (14.4%). Although this male–female ratio is similar to that for the whole sample, we recognize that this subsample is not representative enough to make general claims for the whole sample. However, we perform additional analyses with this smaller dataset to shed light regarding the impact on firm performance of board gender diversity, directors’ family status and human capital. The human capital index subsequently created is composed of four components: higher education level, languages, prizes and recognitions, and professional experience.

Regarding our higher education index, we rank the level according to the quality of the institutions attended. To quantify the value of undergraduate studies, we assign 3 points for degrees granted by foreign educational institutions, 3 points for generally recognized top Colombian universities,Footnote 1 2 points for second-tier Colombian universities with good reputation, and 1 point for other Colombian universities. We assign additional points for education at the master’s level: 3 points if the degree is from a foreign university, 2 points if from a top graduate Colombian program and 1 point otherwise. Additionally, we give 1 point for executives with graduate studies in Colombia different from a master’s degree, 2 points if these other graduate studies are granted by universities abroad, and 3 points if the executive’s additional graduate studies are both local and international. Finally we give 1 point for doctoral studies and 1 additional point for other executive educational programs (non-degree).

To rank languages, we assign 1 point for each language claimed in the CV. We rank prizes and recognitions, assigning 2 points if the executive is among the most successful according to Revista Dinero, an economics magazine in Colombia that publishes a top executive ranking every year, and 1 point for any other type of recognitions. Finally, we quantify the level of experience, allocating 1 point if the executive has worked in the private sector, 1 point if the manager has public sector experience and 3 points if the executive has experience in both public and private sectors. In addition, we assign an extra point for experience as an entrepreneur, university lecturer, or federal/local government official. The “Appendix 2” summarizes the definition and methodology of each variable included in our analysis.

4 Results and discussion

Table 1 shows the distribution of the CEOs and directors in the database over time by gender. Panel A shows the gender distribution for CEOs while Panel B provides the gender distribution for the total sample of directors and for family-related and outside directors. Panel C shows the distribution for male and female directors classified according to their family ties, outsider or family-related, for each gender category. The last column in Table 1 displays the proportions of male and female observations for each category in each of the panels. According to Panel A, with a total of 5094 firm-year observations, our sample includes an average of 463 CEOs per year. However, with an unbalanced panel some years have a higher or lower number of firms, and hence CEO positions. According to our analysis for the estimation of the human capital index, the CEO positions have been occupied by 908 managers. The participation of women as CEOs is low, which is evident in the proportion of total female CEOs over total CEO firm-year observation, equivalent to 7.4%.

Panel B shows that the total number of director positions in our sample for the period under analysis is 36,439. This implies an average board size of approximately 7 members (36,439 director positions over 5094 firm-year observations). Once again, according to our analysis for the estimation of the human capital index, the director positions have been filled by 4907 board members, including 833 female board members. The last column of Table 1 shows that women’s average participation on these boards is 17.5%, a relatively high proportion in comparison to findings in previous studies (Campbell and Mínguez-Vera 2008) for Spain and Carter et al. (2003) and Catalyst (2004) for the United States). CEO positions are less gender diverse than director positions, 7.4% compared to 17.5%. This implies a higher probability for women to participate in firms’ decision-making process through board membership rather than through CEO positions.

In addition, Panels B and C of Table 1 suggest that the relatively higher rate of women’s participation on boards is driven by a higher participation of family female directors. Panel B shows that female directors comprise 26% of total family directors, while outside female directors represent only 14% of total outside directors. According to descriptive statistics in Panel C of Table 1, family male directors represent 26.1% of total male directors, while family female directors represent 43.2% of total female directors. This suggests that family status facilitates the appointment of women to boards.

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics associated with women’s membership on boards of directors. For each variable, the table depicts the mean and standard deviation for the whole sample, for firms with low board participation by women, and for firms with high board participation by women. To build the two subsamples according to the level of women’s participation, we split the observations into two using as a criterion the mean proportion of female directors, 18.5% for the whole sample. Observations below 18.5% constitute the low participation sample, while the high participation sample comprises those observations where female membership is higher than the mean value of 18.5%.Footnote 2 The last two columns report whether the differences in means and medians are statistically significant.Footnote 3

Table 2 reveals that 64.3% of the sample observations belong to firms with low board participation by women. In this group of firms, the average female director participation is equivalent to 6.1%, while in firms with high participation by women the average female director participation is equivalent to 40.8%. In firms with women’s low participation, participation by outside female directors is almost three times the participation of family female directors. Conversely, in firms with high participation of women on boards, participation by family female directors (21%) is higher than participation by outside female directors (19.8%). In addition, in firms with women’s low board participation (low participation firms hereafter), participation by outside male directors is more than three times the participation rate of family male directors, but in firms with high board participation by women (high participation firms hereafter), outside male directors’ participation (35.1%) is only 1.4 times family males’ participation (24.1%). Furthermore, in low participation firms, family directors held 22.2% of the board seats, but in the high participation firms this percentage rises to 45.1%. Hence, firms with more women on boards have more family male and female directors.

The family involvement variables reveal that the CEO is a family member in 24% of the sample; families are the largest shareholder as a group in 19% of the firms, and they exert indirect control through pyramidal ownership in 40.1% of the cases. Within high participation firms, 35% are run by family members, and families are the largest blockholders in 33% of this subsample. Family involvement is higher in high participation firms than in low participation firms. Only indirect family control is higher in low participation firms (41.2%) in comparison to high participation firms (38.1%). Hence, women’s participation on boards tends to be higher when family involvement through management and direct ownership is higher.

Finally, firms with more women on the boards are younger, smaller, less leveraged, more likely to belong to a business group, have more stable boards, offer greater stability to their managers, have a lower probability of being audited by a specialized firm, and show a higher contestability index, perhaps exerted by other family owners.

Table 3 analyzes how different types of directors affect firms’ performance. Regressions follow a general two-way error component model with a matrix dimension of i × t:

where Yit is the industry-adjusted ROA, GR is the vector with directors’ gender-related variables, FI is the vector with family involvement dummies, CG is the vector with the corporate governance controls, which includes ownership and control contestability variables, and X is the vector with the standard financial and idiosyncratic controls.

Column 1 shows that the control variables behave as expected. The variables dividend ratio, firm age, firm size, growth opportunities, and contestability index have a positive and significant effect on the industry-adjusted return on assets (AROA). Long-term leverage, CEO turnover, board turnover, the presence of an auditing firm and our group affiliation dummy have a negative and significant effect on AROA. All these variables are consistent in magnitude and statistical significance in all the models, which leaves us confident that the model is well-specified.

Column 2 includes the regression for female presence on the board of directors and shows a significant negative coefficient (− 0.0083). This implies that one standard deviation in the percentage of women on the board translates into a 0.83% decrease in a firm’s AROA. When we include in column 3 other family involvement variables (family CEO, family ownership, and indirect family control), the size and the statistical significance of the coefficient for female presence decreases but is still significant at a 5% level. This is economically important, given that one standard deviation in female presence reduces AROA by 0.59%.

Results in column 3 are consistent with some international evidence (Triana et al. 2014; Adams and Ferreira 2009) that finds a negative relationship between gender diversity and financial performance, but is inconsistent with the majority of recent country studies discussed above (Vafaei et al. 2015; Gordini and Rancati 2017; Campbell and Mínguez-Vera 2008). These differences could be due to the closely held nature of our sample, which is one of the reasons some authors call for a more detailed analysis of non-listed firms (Wagana and Nzulwa 2016).

To better understand the impact of female directors on firm performance it is relevant to control for family ties. As we argued earlier, family female directors can serve on boards for reasons (e.g., nepotism and dynastic management) other than the usual monitoring and advising role. In contrast, the small fraction of outside female directors available in the directors’ market should embody knowledge and talent, and therefore one would expect their presence on the board to exert a positive impact on a firm’s performance (Hypothesis 4). Table 3, column 4, separates the analysis of outside and family female directors. Consistent with Hypothesis 4, the former has a significant positive impact (0.0089, p < 0.05) while the latter has a significant negative one (− 0.0117, p < 0.01).

As argued above, we also expect a positive impact of family male directors on firm financial performance, explained on the one hand by gender bias and on the other by patriarchal practices in family businesses (Hypothesis 2). Consistent with Hypothesis 2, column 4 in Table 3 shows that the variable for family male directors is positively related to firm performance (0.0112, p < 0.1).

The regression specification tests consistently reject the null hypothesis of no individual effects, according to the Lagrange multiplier test. For this case, the error component model is assumed the true specification, where individual effects are fixed or random. We assume the random effects model is the true model because some variables relevant in our analysis, such as those pertaining to family involvement (e.g., family CEO, direct and indirect ownership, family control) and other variables in the model (e.g., group affiliation, auditing firms, contestability index) are time-invariant dummies.Footnote 4

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics of our human capital index for the subsample of 815 CVs of CEOs and directors. For the whole subsample, education has a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 12, with an average of 4.67; the sub-index languages has a minimum of 1, a maximum of 7, and an average of 1.9; the sub-index prizes and recognitions has a minimum of 0, a maximum of 2, and an average of 0.23. Finally, the sub-index for experience shows a minimum of 1, a maximum of 6, and an average of 2.05. We also show and aggregate the human capital index with a minimum of 3, a maximum of 19, and an average of 8.05.

In Table 4, we show that men score higher on the human capital index compared to women (8.96 versus 8.14). This gender difference is statistically significant at 1%. The mean values of the sub-indexes that comprise the human capital index also exhibit statistically significant gender differences in education (4.74 versus 4.22) at the 1% level and experience (2.08 versus 1.86) at the 5% level. Languages and recognitions show no statistical differences between male and female CEOs or directors.

Retrospectively, these results are consistent with the fact that executives who were CEOs or directors between 1996 and 2006 got their undergraduate degrees between the 1950s and 1970s, when the majority of professionals were men. Hence, it is rational to find a lower level of human capital for women in our analysis.

In Table 5, we study gender differences in the human capital of board members only. Table 5, Panel A, shows that male directors have a higher human capital index on average than women have (9.03 versus 8.20, with p < 1%). The results are similar in all cases; that is, male directors are better educated, speak more languages, hold more prizes and recognitions, and have more experience, although only mean values in education and experience are statistically significant, at a 5 and 1% level, respectively.

Classifying directors by gender (male/female) and family status (family/outsider), we find that directors with the highest human capital index (10.37) are male and family-related. Those with the lowest ranking (6.80) are female and family-related. These are the highest and lowest values in our subsample. The average scores for outside male and female directors are between the two extreme values cited.

When comparing family female directors and outside female directors in this subsample, we find significant differences between their scores on the human capital index (6.80 versus 9.00). This result cannot be regarded as empirical evidence to fully support our Hypothesis 3 given the small size of the subsample. However, it sheds some light on the positive impact on firm performance of outside female directors. As mentioned above, due to gender bias and the glass ceiling effect, outside females should be better prepared professionally to assume top managerial positions. Table 5, Panel B, shows that the score for outsider females is even higher than that for outsider males (9.00 versus 8.86). This is consistent with our initial argument that the few women without family ties who are chosen as directors are likely to exhibit above-average talent manifested in greater education and experience.

Another interesting result for this subsample in Table 5, Panel B, consistent with our Hypothesis 1, is that families seem to prepare male heirs better than female heirs. This partial evidence could suggest that families are predisposed to select male heirs to run the firm and be in charge of the family business (Mulholland 1996; Holgersson 2013). If this is the case, we are likely to find higher human capital scores for family male directors than for either family female directors or outside male directors, just as this restricted subsample shows. As depicted in Table 5, Panel B, the human capital score for family male directors, at 10.37, is the highest of all, much higher than that for family female directors (6.80) and also higher than the value associated with outside male directors (8.86).

We go further, examining the relationship between directors’ gender, their talent and firms’ performance in a multivariate analysis. However, and as explained before, due to the lower level of information disclosure in Colombia, it was not possible to find CVs for all directors in our sample. Table 6 shows the distribution of CVs, and hence the human capital index coverage for our sample of directors. Columns 1–3 show information pertaining to directors, and columns 4–6 show the board seats held by this subsample of directors (observations). As shown in columns 1–3, we were able to build the human capital index for 14.8% of the directors in our sample, with similar patterns for males (15.1%) and females (13.2%). This coverage ratio is similar when analyzing board seats instead of directors. The coverage ratio in column 6 is a little higher and equal to 16.1%. Once again, results are similar when splitting the coverage ratio for board seats held by men (16.4%) and women (14.2%).

We analyze the subsample to test whether it is statistically representative in terms of industry distribution, share of family/non-family directors, and female/male directors, among other sample characteristics. Although the subsample still keeps observations for nine of the eleven industrial sectors, it has different characteristics when compared to the full database. For example, the proportion of female directors rises to 34% (from 18.5% in Table 2) and the proportion of outside female directors rises to 20% (from 10%). Hence, we cannot say that this smaller subsample delivers representative results concerning our larger sample.

With this caveat in mind, we regress firm performance with different estimations of our human capital index. Table 7 analyzes how different types of directors and their human capital affect firms’ performance. Regressions follow Eq. 1 explained above, and most of the main control variables keep their size, signs and statistical significance. Total observations went from 4568 to 861 in column 6, to 717 in columns 2 and 3, then 107 in column 5, and 62 in column 4. Column 1 in Table 7 replicates the regression in column 2, Table 3, to facilitate comparison. Column 2, Table 7, uses the female directors’ human capital index instead of the proportion of female directors on the board, and this variable shows a significant and positive impact on firm performance. Column 3 includes both variables and shows that human capital and not female board participation is significant for explaining a firm’s performance. In the same vein, columns 4–6 show similar results where, at least for this restricted subsample, human capital and not directors’ gender and classification explains firm performance.

Finally, we recognize in our econometric setup the possibility of double causality. Following Hermalin and Weisbach (2003) and Terjesen et al. (2016), we assume that all board-related variables, including the percentages of family and outside female and male directors on the board, are endogenously related to firm performance. Bhagat and Jefferis (2002) and Hermalin and Weisbach (1991) suggest that the use of lagged variables in panel regressions could serve to control for potential biases from double causality. Hence, we replicate the regressions in Tables 3 and 7 using as independent variables the lagged values of Female Directors [%], Family-Female Directors [%], Family-Male Directors [%], Outside-Female Directors [%], along with the lagged values of their Human Capital Indexes measures. The main results find statistical support under these specifications (not shown but available upon request).

However, it is necessary to recognize that using lagged variables does not always resolve the problem of double causality. Hence, to tackle this issue with the available data, the empirical model includes the instrumented estimations for our board-related variables. Following Arellano and Bond (1991) and Terjesen et al. (2016), we use the lagged levels of the endogenous regressors along with other potential exogenous variables to guarantee the validity of the instruments. We choose the lag percentages of outside directors and the lag of the board size. As in Terjesen et al. (2016), the model will then choose the best linear combination of these instruments for each instrumented independent variable. We run two-stage least squares estimations and in most cases, regression coefficients keep the sign, magnitude and significance of the original regressions (not shown but available upon request). The endogeneity test results imply that the board-related endogenous regressors cannot be treated as exogenous because they are endogenously related to firm performance. The Sargan statistics results suggest that the set of instruments is valid. In the same vein, the F test of the validity of the instruments suggests the use of valid instruments (Stock et al. 2002). Finally, Hausman tests suggest that in most cases the original model’s results are preferable on the grounds of efficiency.

Another limitation in our paper is the accurate identification of family ownership. Family firms might be reluctant to offer insights into their ownership structure. Hence, the sample we use might have a bias as only those companies that report detailed records of their ownership are included. However, we made the decision to remove firms that lack ownership details and sufficient information to identify majority shareholders (direct ownership) as well as pyramidal ownership structures (indirect ownership). We apply this restriction because otherwise it would not be possible to accurately identify firms with family involvement. In our context, this type of family involvement is extremely common (e.g., business groups). However, if our sample included firms without information about the ownership structure, we could be mistakenly considering firms under family control through ownership as if they did not have any family involvement. Or we could be excluding some family firms that lack complete information regarding their ownership structure.

With these limitations in mind, overall, our results indicate that gender diversity by itself is not what drives performance; rather, it is the human capital of the directors, regardless of their family status.

5 Conclusion

In this paper we contribute to the discussion about how gender diversity on the board of directors affects firm financial performance. Looking at a sample of mostly closely held firms in Colombia during the period 1996–2006, we find that directors’ gender and family status have a differentiated effect on firm performance. While outside female and family male directors have a positive impact on firm financial performance, family female directors have the opposite effect.

An interpretation for these results, consistent with the literature, suggests that, on one hand, female directors with family ties are likely to have a seat in the board for reasons other than talent (nepotism and dynastic management). On the other hand, independent female directors without ties to the business-controlling family are likely to exhibit exceptional talent in order to qualify for board membership (overcoming the glass ceiling effect and gender bias). In addition, these results are also consistent with the literature positing that male heirs are somehow chosen and trained in advance to run the firm and the family business in general (gender bias in family firms’ succession processes).

Notes

We follow the 2015 Colombian University Ranking Model of Indicators regarding education performance (MIDE by its Spanish acronym) as calculated by the Colombian Ministry of Education.

In the discussion of Table 1, we state that the 17.5% rate of women’s participation on the boards is calculated by dividing the total number of female directors’ observations over the total number of directors’ observations in our sample. The mean value of the female directors in the discussion of Table 2 is slightly different because it represents the average for the different percentage of board seats occupied by women in each of the 5094 firm-year observations.

The Wilcoxon rank test is used as an alternative to the Student’s t–test when the population cannot be assumed to be normally distributed.

The null hypothesis in the Hausman test assumes that the random effects model is the true model and the variance–covariance matrix (VCE) is efficient. Therefore, one cannot reject the null hypothesis that the difference in the regression coefficient is systematic between the fixed versus random effects specifications. The full specification displayed in regression Eqs. 1–4 failed to pass the Hausman specification test. However in the presence of heteroscedastic residuals, which is the case, the scope of this test is limited. Instead, Cameron and Trivedi (2010) recommend related tests based on bootstrapping methods. We run reduced empirical models (not shown) that passed the Hausman test but with high costs in terms of explanatory power. Hence, the random effects model is chosen. However, our regressions use feasible generalized least squares (FGLS) to control for heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation in our panel data set.

References

Acero I, Alcalde N (2016) Controlling shareholders and the composition of the board: special focus on family firms. Rev Manag Sci 10(1):61–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-014-0140-x

Adams RB, Ferreira D (2007) A theory of friendly boards. J Finance 62:217–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2007.01206.x

Adams RB, Ferreira D (2009) Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. J Financ Econ 94:291–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.10.007

Adams R, Kirchmaier T (2015) Barriers to boardrooms. In: ECGI - Finance Working Paper No. 347/2013; Asian Finance Association (AsFA) 2013 conference. Available at SSRN https://ssrn.com/abstract=2192918

Ahern KR, Dittmar AK (2012) The changing of the boards: the impact on firm valuation of mandated female board representation. Q J Econ 127(1):137–197

Anderson RC, Reeb DM, Upadhyay A, Zhao W (2011) The economics of director heterogeneity. Financ Manag 40:5–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-053X.2010.01133.x

Andres C (2008) Large shareholders and firm performance—An empirical examination of founding-family ownership. J Corp Finance 14(4):431–445

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58:277–297

Arfken DE, Bellar SL, Helms MM (2004) The ultimate glass ceiling revisited: the presence of women on corporate boards. J Bus Ethics 50:177–186. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000022125.95758.98

Barontini R, Caprio L (2006) The effect of family control on firm value and performance: evidence from continental Europe. Eur Financ Manag 12(5):689–723

Barth E, Gulbrandsen T, Schønea P (2005) Family ownership and productivity: the role of owner–management. J. Corp. Finance 11(1):107–127

Bennedsen M, Nielsen KM, Pérez-González F, Wolfenzon D (2007) Inside the family firm: the role of families in succession decisions and performance. Q J Econ 122:647–691. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.2.647

Bertrand M, Schoar A (2006) The role of family in family firms. J Econ Perspect 20(2):73–96

Bertrand M, Johnson S, Samphantharak K, Schoar A (2008) Mixing family with business: a study of Thai business groups and the families behind them. J Financ Econ 88(3):466–498

Bhagat S, Jefferis J (2002) The econometrics of corporate governance studies. MIT Press, Cambridge

Bianco M, Ciavarella A, Signoretti R (2015) Women on corporate boards in Italy: the role of family connections. Corp Gov Int Rev 23:129–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12097

Burkart M, Panunzi F, Shleifer A (2003) Family firms. J Finance 58(5):2167–2201

Byron K, Post C (2016) Women on boards of directors and corporate social performance: a meta-analysis. Corp Gov Int Rev 24(4):428–442

Cameron CA, Trivedi P (2010) Microeconometrics using stata. Stata Press College Station, Texas

Campbell K, Mínguez-Vera A (2008) Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance. J Bus Ethics 83:435–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9630-y

Carter DA, Simkins BJ, Simpson WG (2003) Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financ Rev 38:33–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6288.00034

Carter DA, D’Souza F, Simkins BJ, Simpson WG (2010) The gender and ethnic diversity of US boards and board committees and firm financial performance. Corp Gov Int Rev 18:396–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2010.00809.x

Caselli F, Gennaioli N (2013) Dynastic management. Econ Inq 51(1):971–996

Catalyst (2004) The bottom line: connecting corporate performance and gender diversity. Catalyst, New York

Chapple L, Humphrey JE (2014) Does board gender diversity have a financial impact? Evidence using stock portfolio performance. J Bus Ethics 122:709–723. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1785-0

Cook A, Glass C (2014) Women and top leadership positions: towards an institutional analysis. Gend Work Organ 21:91–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12018

Cucculelli M, Micucci G (2008) Family succession and firm performance: evidence from Italian family firms. J Corp Finance 14(1):17–31

Dale-Olsen H, Schøne P, Verner M (2013) Diversity among Norwegian boards of directors: does a quota for women improve firm performance? Fem Econ 19:110–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2013.830188

Dawson LM (1997) Ethical differences between men and women in the sales profession. J Bus Ethics 16:1143–1152. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005721916646

Dezsö CL, Ross DG (2012) Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation. Strateg Manag J 33:1072–1089. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1955

Erhardt NL, Werbel JD, Shrader CB (2003) Board of director diversity and firm financial performance. Corp Gov Int Rev 11:102–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8683.00011

Farrell KA, Hersch PL (2005) Additions to corporate boards: the effect of gender. J Corp Finance 11:85–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2003.12.001

García-Meca E, García-Sánchez IM, Martínez-Ferrero J (2015) Board diversity and its effects on bank performance: an international analysis. J Bank Finance 53:202–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.12.002

Gómez-Mejía LR, Haynes KT, Núñez-Nickel M, Jacobson KJ, Moyano-Fuentes J (2007) Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Adm Sci Q 52(1):106–137

Gordini N, Rancati E (2017) Gender diversity in the Italian boardroom and firm financial performance. Manag Res Rev 40:75–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-02-2016-0039

Gregory MR (2009) Inside the locker room: male homosociability in the advertising industry. Gend Work Organ 16:323–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00447.x

Gregory-Smith I, Main BG, O’Reilly CA (2014) Appointments, pay and performance in UK boardrooms by gender. Econ J 124(574):109–128

Hermalin B, Weisbach M (1991) The effect of board composition and direct incentives on firm performance. Financ Manag 20:101–112

Hermalin B, Weisbach M (2003) Boards of directors as an endogenously-determined institution: a survey of the economic literature. Econ Policy Rev 9:7–26

Hillman AJ (2015) Board diversity: beginning to unpeel the onion. Corp Gov Int Rev 23:104–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12090

Holgersson C (2013) Recruiting managing directors: doing homosociality. Gend Work Organ 20:454–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2012.00595.x

Iannotta M, Gatti M, Huse M (2016) Institutional complementarities and gender diversity on boards: a configurational approach. Corp Gov Int Rev 24(4):406–427

Ibarra H (1992) Homophily and differential returns: sex differences in network structure and access in an advertising firm. Adm Sci Q 37(3):422–447

Joshi H, Makepeace G, Dolton P (2007) More or less unequal? Evidence on the pay of men and women from the British birth cohort studies. Gend Work Organ 14:37–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2007.00331.x

Kılıç M, Kuzey C (2016) The effect of board gender diversity on firm performance: evidence from Turkey. Gend Manage Int J 31:434–455. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-10-2015-0088

Kumar P, Zattoni A (2016) Corporate governance, board gender diversity and firm performance. Corp Gov Int Rev 24:388–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12172

Liu Y, Wei Z, Xie F (2014) Do women directors improve firm performance in China? J Corp Finance 28:169–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2013.11.016

Maury B, Pajuste A (2005) Multiple large shareholders and firm value. J Bank Finance 29:1813–1834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.07.002

Marquardt C, Wiedman C (2016) Can shareholder activism improve gender diversity on corporate boards? Corp Gov Int Rev 24(4):443–461

Mazzola P, Marchisio G, Astrachan J (2008) Strategic planning in family business: a powerful developmental tool for the next generation. Fam Bus Rev 21(3):239–258

Mehrotra V, Morck R, Shim J, Wiwattanakantang Y (2013) Adoptive expectations: rising sons in Japanese family firms. J Financ Econ 108:840–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.01.011

Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J (2012) Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:16474–16479. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211286109

Moss-Racusin CA, van der Toorn J, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J (2014) Scientific diversity interventions. Science 343:615–616. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1245936

Mulholland K (1996) Gender power and property relations within entrepreneurial wealthy families. Gend Work Organ 3:78–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.1996.tb00050.x

Nguyen DDL, Hagendorff J, Eshraghi A (2015) Which executive characteristics create value in banking? Evidence from appointment announcements. Corp Gov Int Rev 23:112–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12084

Pérez-González F (2006) Inherited control and firm performance. Am Econ Rev 96(5):1559–1588

Pollak RA (1985) A transaction cost approach to families and households. J Econ Lit 23:581–608. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2725625

Post C, Byron K (2015) Women on boards and firm financial performance: a meta-analysis. Acad Manag J 58:1546–1571. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0319

Ramly Z, Chan SG, Mustapha MZ, Sapiei NS (2017) Women on boards and bank efficiency in ASEAN-5: the moderating role of the independent directors. Rev Manag Sci 11(1):225–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-015-0186-4

Rose C (2007) Does female board representation influence firm performance? The Danish evidence. Corp Gov Int Rev 15:404–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2007.00570.x

Sageder M, Mitter C, Feldbauer-Durstmüller B (2016) Image and reputation of family firms: a systematic literature review of the state of research. Rev Manag Sci (Forthcoming). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-016-0216-x

Schmid T, Urban D (2017) The economic consequences of a ‘Glass-Ceiling’: women on corporate boards and firm value (November 7, 2017). AFA 2016 San Francisco Meetings Paper. Available at SSRN https://ssrn.com/abstract=2344786

Schultz TW (1961) Investment in human capital. Am Econ Rev 51(1):1–17

Seierstad C (2016) Beyond the business case: the need for both utility and justice rationales for increasing the share of women on boards. Corp Gov Int Rev 24(4):390–405

Shrader CB, Blackburn VB, Iles P (1997) Women in management and firm financial performance: an exploratory study. J Manag Issues 9:355–372. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40604152

Smith BF, Amoako-Adu B (1999) Management succession and financial performance of family controlled firms. J Corp Finance 5(4):341–368

Sraer D, Thesmar D (2007) Performance and behavior of family firms: evidence from the French stock market. J Eur Econ Assoc 5(4):709–751

Steinpreis RE, Anders KA, Ritzke D (1999) The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: a national empirical study. Sex Roles 41:509–528. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018839203698

Stock J, Wright J, Yogo M (2002) A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments. J Bus Econ Stat 20:518–529

Tavora I (2012) Understanding the high rates of employment among low-educated women in Portugal: a comparatively oriented case study. Gend Work Organ 19:93–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00489.x

Terjesen S, Couto EB, Francisco PM (2016) Does the presence of independent and female directors impact firm performance? A multi-country study of board diversity. J Manag Gov 20(3):447–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-014-9307-8

Triana MDC, Miller TL, Trzebiatowski TM (2014) The double-edged nature of board gender diversity: diversity, firm performance, and the power of women directors as predictors of strategic change. Organ Sci 25:609–632. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2013.0842

Vafaei A, Ahmed K, Mather P (2015) Board diversity and financial performance in the top 500 Australian firms. Aust Account Rev 25:413–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/auar.12068

Van der Walt N, Ingley C, Shergill GS, Townsend A (2006) Board configuration: are diverse boards better boards? Corp Gov Int J Bus Soc 6:129–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700610655141

Villalonga B, Amit R (2006) How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value? J Financ Econ 80(2):385–417

Villalonga B, Amit R, Trujillo MA, Guzmán A (2015) Governance of family firms. Annu Rev Financ Econ 7:635–654

Wagana DM, Nzulwa JD (2016) Corporate governance, board gender diversity and corporate performance: a critical review of literature. Eur Sci J 12:221–233. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2016.v12n7p221

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors are in alphabetical order and contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

González, M., Guzmán, A., Pablo, E. et al. Does gender really matter in the boardroom? Evidence from closely held family firms. Rev Manag Sci 14, 221–267 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0292-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0292-1