Abstract

A combination of improvements in patient survival, increasing treatment duration, and the development of more expensive agents has led to a doubling of per-capita spending on cancer medicines in Ireland (2008–2018). Despite this, access to new drugs is poor in comparison to other EU countries. We examine methods to optimise oncology drug spending to facilitate access to newer anticancer agents. Key targets for spending optimisation (biosimilar use, clinical trials and expanded access programs, waste reduction, avoidance of futile treatment, and altered drug scheduling) were identified through an exploratory analysis. A structured literature search was performed, with a focus on articles relevant to the Irish Healthcare system, supplemented by reports from statutory bodies. At the present time, EMA-approved agents are available once approved by the NCPE. Optimising drug costs occurs through guideline-based practice and biosimilar integration, the latter provides €80 million in cost savings annually. Access to novel therapies can occur via over 50 clinical trials and 28 currently available expanded access programmes. Additional strategies include reversion to weight-based immunotherapy dosing, potentially saving €400,000 per year in our centre alone, vial sharing, and optimisation of treatment schedules. A variety of techniques are being employed by oncologists to optimise costs and increase access to innovation for patients. Use of biosimilars, drug wastage, and prescribing at end of life should be audited as key performance indicators, which may lead to reflective practice on treatment planning. Such measures could further optimise oncology drug expenditure nationally facilitating approval of new agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The past two decades have been characterised by a significant expansion in new treatment options. While only one new treatment was approved annually in the 1990s, by 2020, 10 new medicines were being approved per year, with 17 new approvals in 2021 [1]. Alongside improvements in diagnostics, surgery, and supportive care, these developments have greatly improved outcomes for many of our patients, for example in women diagnosed with ER + /Her2 + de novo metastatic breast cancer, approximately 75% are still alive after 5 years, compared to under 30% of those diagnosed in the pre-trastuzumab era [2].

As patients with advanced disease live longer, treatment durations are increasing, and in addition to the high costs of some of the more newly authorised drugs (Table 1), this has led to a commensurate increase in government spending, with per-capita spending on cancer medicines in Ireland doubling from €29 to €64/capita between 2008 and 2018 [3]. Annual drug spending exceeds €300 million [3], representing 27% of state spending on cancer, and 0.1% of total GDP. Despite this, Irish patients access to new oncology drugs remains relatively poor [1], at least partly due to financial constraints. Of the new drugs approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) between 2017 and 2020, only 51% were reimbursed by the HSE at the beginning of 2022, placing Ireland second last among the EU-15 countries [1].

Alongside advocating for further resources, it is essential that oncologists try to maximise value for money using the available resources. In this article, we will examine mechanisms to provide high-quality care while reducing drug spending, including accessing treatment via expanded access programmes and clinical trials, use of biosimilar agents, optimisation of drug scheduling and dosing, reduction of drug wastage, and avoidance of treatment which is unlikely to be beneficial, particularly at the end of life.

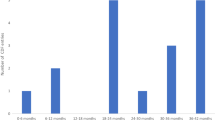

Clinical trials

Clinical trials afford patients access to novel therapies and are essential in driving continued progress and advances in cancer care. Furthermore, they have clear economic benefits, as in industry-sponsored studies, the trial drugs are provided free of charge. The cost implications are significant: in a pre-pandemic review in Cork University Hospital, novel therapies were administered to patients to a value of €50,000–€90,000 each month [7]. A review of clinical trials currently open through Cancer Trials Ireland demonstrates 36 solid-tumour studies offering patients access to investigational agents (Table 2), with an additional 14 haematology trials open. Of the 287 patients accrued to these studies in 2022, 137 (48%) participated in trials investigating immunotherapies, including some of the most expensive marketed drugs. A previous analysis estimated that the return from state investment into cancer trials in Ireland is twice that which is invested, representing a significant return on investment to the state [8]. In 2016 the combined €3.63m funding from the Exchequer and other grants resulted in a saving of an estimated €6.5m in the cost of cancer drugs. Additionally, nearly €6m in tax revenues was generated with a contribution of €16.5m to Ireland’s gross domestic product (GDP) as well as support for over 230 largely highly skilled jobs [7]. One clinical trials unit included in this analysis reported that each €1 in grant funding received, yielded €3 in income from industry for trials, supporting the need for continued expansion and investment in cancer research units nationwide. In international studies, average drug cost avoidance per patient has been estimated at €10,000 to €16,000 [9, 10], with cost savings per centre up to €6 million a year [11], significantly exceeding the costs associated with running a clinical trial [12].

Fewer than 5% of patients participate in clinical trials globally, and Irish data is consistent with this [13, 14]. Where trials are offered to patients, fewer than 5% of patients decline participation [13, 14], and the major barrier remains a lack of suitable open trials for tumour type/stage within a reasonable travel distance for the patient.

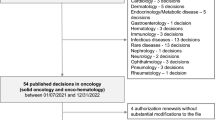

Expanded access programmes

Expanded access programmes (EAPs) allow patients to access new drugs outside of clinical trials [15], and may be utilised if a drug is approved by regulatory bodies but not yet reimbursed by the state [16]. A common model for these programmes is that the programme sponsor (typically the pharmaceutical company that hopes to market a new drug) provides the drug for free to selected patients after an application by their treating consultant; however, the programme may close to new patients at any time, sometimes before reimbursement is agreed. In Ireland, unlike most other European countries, there is no national protocol or standardised approach for the implementation of EAPs [17]. Consequently, there is a gap in the literature in terms of data and research examining the role that these programmes play in current cancer patient care in Ireland. Cronin et al. [18] assessed the role of expanded access medications in 3 oncology units. Over a 9-year period 193 patients had been enrolled in programmes. Importantly, the results also show that the number of EAPs being accessed increased annually, emphasising the increasing gap between drug approval and drug reimbursement in this jurisdiction. The Irish Society of Medical Oncology (ISMO) has established a registry of expanded access programmes to ensure equity of access of patients. A total of 33 drugs are currently provided for a total of 50 different cancer indications, reflecting the important role of EAPs in the landscape of cancer practice nationally (Table 3).

Biosimilars

The term biosimilar describes a biologic drug which has been developed such that there are no ‘clinically meaningful differences’ between it and the reference medicine which has already been licenced [19]. Although the EU considers EMA licensed biosimilars interchangeable [20], unlike generic drugs, the Health (Pricing and Supply of Medical Goods) Act 2013 in Ireland specifically excludes biosimilars from being added to the ‘list of interchangeable medicinal products’, so that these medicines cannot undergo generic substitution. Because of this, clinicians must intentionally decide to switch to these, if appropriate.

To provide an idea of the scope of the cost savings provided by biosimilars, a 2019 study modelled the impact of choosing biosimilar trastuzumab (a monoclonal antibody targeting HER2) instead of its reference product (Herceptin) in 28 European countries over 5 years [21], determining that €1.13–€2.27 billion could be saved based on epidemiological data [21]. The same model estimated that 55,082–116,196 additional patients could gain access to trastuzumab over the 5-year period [21]. Real-world data has revealed savings of GBP £100 million for trastuzumab and adalimumab biosimilars the UK National Health Service (NHS) in 2018 alone [22].

Across all biosimilars, annual savings in Ireland exceed €80 million [23]. Biosimilars currently account for 52–54% of the market share of oncology biologicals in Ireland [23, 24], compared to over 90% in Austria, the Netherlands, and Norway, suggesting scope for further expansion [24].

A 2021 literature review investigated the impact of non-medical switching policies which replace reference biologic products with biosimilars [25], and found that cost savings were achieved in most cases [25], but the concept of biosimilar substitution does not currently have sufficient support from prescribers [26]. Some barriers to more extensive uptake globally identified include patient and prescriber perception of biosimilars, lack of awareness, and issues regarding interchangeability and substitution of biosimilars [27]. Recently updated American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines support interchangeable use of biologics, and note that to date, no immunogenicity concerns for any approved oncology biosimilars have been identified by the FDA [28]. As experience with using biosimilars has grown substantially, hesitation from oncologists may reduce over time [22]. It has been recommended that there should be scheduled evaluations of patient experience included in biosimilar implementation plans [29], which may help strengthen the case for increased use.

Drug dosing and scheduling

Historically, drug dosing has been determined by the maximum tolerated dose established in phase 1 trials; however, moving to a minimum efficacious dose may be more appropriate. A number of drugs are commonly used at a lower dose than that in their original trials [30], such as the PARP inhibitor niraparib, where the use of a 200 mg starting dose in patients weighing < 77kg is associated with better tolerance and can save €2700 compared to a 300 mg dose [6], without impact on survival outcomes [31].

While immunotherapies have improved outcomes for many patients, controversy exists around the 200/400 mg (pembrolizumab) or 240/480 mg (nivolumab) ‘flat’ doses that are typically prescribed, irrespective of body surface area. While early studies with pembrolizumab investigated a 2 mg/kg dose [32,33,34], when pharmacokinetic data suggested a 200 mg flat dose provided similar exposure distributions [35], research shifted to using this as a standard. As the median patient weight in this study was 77.2 kg, most patients received more product via flat-dose dispensing. In one Cork University Hospital study [36], flat dosing resulted in increased costs of €22,693 and €4018 per patient (pembrolizumab and nivolumab, respectively) in comparison to weight based, with an annual total cost of almost €400,000 in our hospital alone. Current product licences [37, 38], National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP) protocols [39], and most recent studies use flat-based dosing. Consequently, weight-based dosing is an off-label use; however, a global reversion to use of weight-based pembrolizumab dosing could save $0.8 billion per year [40].

Chemotherapy de-escalation in metastatic colorectal cancer is well established, where patients may receive 8–24 weeks of ‘induction’ chemotherapy with a fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin/irinotecan before moving to single-agent maintenance. While oxaliplatin and irinotecan are not expensive drugs by the standards of immunotherapies, no survival advantage has been seen by continuing them in meta-analysis [41]. Similarly, ‘treatment holidays’ can improve quality of life and tolerance of treatment in those with stable/responding advanced disease, particularly in colorectal cancer. While the COIN study (observation and reintroduction of therapy as-needed compared to maintenance therapy) did not meet non-inferiority endpoints [42], a later meta-analysis found no evidence of impaired survival [43], with similarly positive findings in the FOCUS4-N trial [44], while using cetuximab on an observation/reintroduction schedule saves over £35,000 per patient annually [45, 46] (almost €49,000, adjusting for inflation). In addition to savings on drug products, drug de-escalation and treatment holidays reduce demands for slots on oncology daywards, a resource which is severely limited in many hospitals [47], and which cannot easily be increased without major investment. Unlike other countries [48], Ireland does not mandate stopping immunotherapy after any set period [39]. The optimal duration of immunotherapy in metastatic disease is being investigated in trials such as DANTE [49], Safe Stop, and STOP-GAP [50], and if strong evidence is found for treatment interruptions after 2 years, this may be a significant cost reduction.

Some agents have interactions with food, which could potentially be leveraged to reduce drug costs. Abiraterone (a hormonal agent used in advanced prostate cancer) is typically taken as a 1000 mg dose on an empty stomach. A 250 mg dose taken with a high-fat meal may yield similar control of PSA [51] to the conventional 1000 mg dose, though long-term survival outcomes have not been reported. This strategy is being used in some low-income countries [52], and the US National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines include 250 mg with food as an option for patients where financial toxicity limits access to care [53]. This is not being practised in Irish centres, and a 250 mg dose is not available in the Irish market. Coadministration of grapefruit with the kinase inhibitor lapatinib could also reduce the dose required [54,55,56], potentially saving over €2000 per patient per month [6]. Similar avenues are being explored with other agents [57, 58], though no research on clinical outcomes has been conducted; thus, these strategies are not established enough to use in our patients.

Avoidance of futile treatments

Preventing the use of futile treatments in palliative patients is another method of reducing the financial impact of cancer care. The receipt of systemic anticancer therapy (SACT) at the end of life is associated with poor quality of death, death in hospital, and higher health care costs [59, 60]. Consequently, 30-day mortality rate after SACT is used as a key performance indicator (KPI), both in Ireland [61] and internationally [62]. The National Cancer Strategy (2017–2026) recommends that < 25% of patients should receive SACT in the last month of life [63]. Early referrals to palliative care are associated with less aggressive end of life care [64], improved overall survival, and quality of life [65].

A retrospective study of 582 patients with advanced malignancies that underwent treatment at two Dublin hospitals between 2015 and 2017 found that 22% and 6% received SACT in the last 4 and 2 weeks of life, respectively [66]. A Cork and Mercy University Hospital study assessing immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) demonstrated 20% of metastatic patients prescribed ICI received this in the last 30 days of life [67]. In both studies the institutions were compliant with the Cancer Strategy’s KPI and the majority of patients (92% [67] and 88% [66]) were referred to palliative care. The timing of palliative care referrals is important, with O’Sullivan et al. demonstrating that late palliative care referrals (≤ 3 months before death) were associated with hospitalisations in the last month of life [67]. Adopting early palliative care referrals allows patients and their caregivers time to manage treatment expectations, plan end-of-life care, and ultimately reduce healthcare costs [64, 68, 69].

In addition to overtreatment in the advanced setting, efforts must be made to de-escalate unnecessary treatments in patients undergoing radical intent therapy. In breast cancer, trials have sought to reduce the number of agents given adjuvantly in HER2-positive breast cancer. Biomarkers can be used to guide adjuvant SACT selection: in early ER-positive breast cancer, the use of a somatic 21 gene recurrence score led to a 62.5% reduction in chemotherapy in Irish patients, saving the health system €1,900,000 over 8 years. In other solid tumours, circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) is being investigated as a de-escalation tool. In the dynamic study, stage II colorectal cancer patients that were ctDNA negative postoperatively had adjuvant chemotherapy omitted, with no impact on the primary endpoint of 2-year recurrence-free survival [70]. This technology does not yet have the same sensitivity for adjuvant treatment selection in other cancers, such as NSCLC, where atezolizumab still provides benefit in ctDNA-negative patients [71].

Reducing drug wastage

Apart from strategies to look at reducing spending, we must try to ensure that the money we do spend is used economically. Drug wastage accounts for 4–18% of all cancer drug spending in the USA [72,73,74], and while some of this is unavoidable, drug waste mitigation strategies have been shown to reduce drug spending by up to 17% [74]. Given the €300 million annual spending, even a small reduction in wastage is likely to be very impactful.

Reducing wastage within the hospital

Many drugs are dispensed as single-patient vials; however, these often contain more product than a typical patient needs, with up to 33% of product wasted in some cases [73]. Guidelines in many countries advise that once opened, vials must be disposed of within 6 hours [75], but even within these constraints, saving the ‘waste’ product from two or more vials to later formulate a dose for an extra patient (‘vial sharing’) can result in significant savings. With the addition of steps such as dose banding (already standard NCCP policy), or grouping patients being treated with the same drugs on the same days, up to 45% of drug waste expenditure can be avoided [76]. Closed-system drug transfer devices used in compounding may maintain drug sterility beyond the 6-hour window [77], allowing significantly more vial sharing [78], but were not yet universal in Irish hospitals at the time of last audit [79].

We have already discussed above how the adoption of flat dosing may not be beneficial—while this practice does reduce ‘wastage’ in theory, in reality, it moves us from merely discarding leftover drug to infusing leftover drug into patients.

Reducing wastage of oral treatments

For patients who receive oral anti-cancer therapy, drug wastage is experienced by 25–41% of patients [80,81,82,83], and in those who discontinue treatment unexpectedly, 46–85% [83, 84] have ‘leftover’ doses. The cost of these drugs can be significant, with unopened packages worth a median of €2600 per patient in a Dutch study [83].

Traditionally, such medications are discarded; however, several drug repositories are now established, primarily in the USA, such as the Wexner Medical Center Oral Oncology Drug Repository Program [85], and have been endorsed by ASCO guidelines [86]. These allow patients to donate leftover medications, with the intent of these being used for un- or underinsured patients, and one European scheme found a 68% waste reduction, with net savings of $1591 in selected cohorts [87]. In non-oncological studies, most patients indicate willingness to accept re-dispensed medications [88, 89], while in a small oncology study, theoretical willingness to participate in drug reuse was over 80% [90]. To our knowledge, no adverse outcomes have been reported from existing repository programmes.

In patients at higher risks of toxicity, consideration could be given to how medications are dispensed, both by modifying the dosage formulations administered and by split-fill dispensing, where patients may collect only part of an oral cycle at a time. This keeps residual medicines within the pharmacy supply chain and allows drugs to be reallocated to other patients. Wastage via these mechanisms can be reduced significantly [91] in up to 34% of patients [81], saving $1000 [80, 81] per patient. This may be particularly important with more expensive oral agents, such as palbociclib, in which at least 18% of women require a dose reduction [92], with an estimated cost of approximately $5000 per patient [92,93,94]. Anticipating the potential for dose reductions when deciding how the prescription should be formulated may be another cost saver in some cases (see Table 4). While these methods are slightly more inconvenient for the patient, their economic advantages are worth considering, especially in the initial weeks of treatment. Unlike other strategies, these methods can easily be implemented by an individual clinician without significant administrative hurdles.

Discussion

We have outlined potential strategies for optimising drug spending without impacting patient outcomes (Table 5). While some of these will require an initial administrative or infrastructural investment, such as altering pharmacy compounding procedures or opening local access to new clinical trials, many others can be undertaken by an individual clinician almost immediately, such as investigating options for early access drugs, moving to split fill dispensing, or de-escalating individual treatments. Though the individual impact of these simpler interventions is smaller, the cumulative effect if all staff are mindful of costs is likely to be very significant.

At the same time, some of the cost optimisations discussed here require local or national policy changes, and significant investment of time and effort from oncology physicians, pharmacists, and other staff. While reducing spending in one area will increase funding available in other areas, and hence indirectly increase access to new drugs or treatments, oncology funding is not ringfenced, and it is possible that ‘savings’ from the oncology sector may be reallocated to an entirely different area of government spending. Allowing cost savings to be reinvested locally would require significant policy change. One precedent for this is the ‘Best Value Biologic’ initiative, used in rheumatology for drugs such as adalimumab, in which the HSE Medicines Management Programme issued information for prescribers on the selected preferred biosimilars [95], and provided a €500 gain share to the hospital for each patient switched to a preferred biosimilar [95], saving €22.7 million in a year [95]. After national rollout of NCIS, a central NCCP-led review of biosimilar usage patterns could be conducted to estimate potential cost savings of further biosimilar use and the impact of a similar incentive strategy in oncology. If successful, this could be expanded to other areas of cost optimisation; however, it would require a HSE and hospital commitment that incentive funding was provided in addition to routine funding increases, not instead of.

The current (2017–2026) Cancer Strategy [63] aimed to increase participation in therapeutic clinical trials to 6% by 2020. Updated figures were not available as of 2021 [61], and the NCCP aims to improve intelligence gathering via the National Cancer Information System after its national implementation. Monitoring of this KPI is essential, and we must continue investing in our hospitals, investigators, and trials units, to make Irish study sites maximally attractive to sponsors, as well as develop additional non-industry sponsored trials. In addition to trials investigating new agents, increased funding for investigator-initiated trials could focus on dose and scheduling optimisation. The ASCO Value in Cancer Care consortium is continuing to explore avenues such as leveraging drug interactions to achieve cost savings [96], and this is an evolving research area that may yield more options in the future.

Although an informal database of the expanded access programmes currently open has been created, this is maintained by ISMO volunteers, and no information on activity or patient outcomes is available, except to the programme sponsor. A national database for all expanded access programmes would be desirable, with mandatory registration by prescribers. This would provide real-world data on activity and toxicity, often in rare tumour subtypes, facilitate regulatory bodies in approval assessments, and would also ensure equity of access for patients. Ideally, this would be linked with the National Cancer Information System (NCIS), a single national computerised system that will record and store information of cancer diagnosis and treatments for all patients treated within the public system. First planned in 2013, this system is slowly being expanded, but does not yet capture data from all sites, limiting our ability to capture data on other KPIs, such as those related to chemotherapy in the last month of life [61]. In the interim, individual cancer units should audit this themselves, alongside auditing rationalisation of other medications.

‘Drug wastage’ is not being captured at a national level in Ireland, and this could be considered for inclusion in the next National Cancer Strategy. While some wastage is inevitable to allow efficient patient flow through the dayward (e.g. many units begin compounding low-cost drugs before all blood results are finalised for patients who appear well, to minimise waiting times), at a hospital level, residual drug contents in vials, and dose reductions/treatment cancellations after drugs have been compounded should be monitored, and investment could be considered in closed-system transfer devices where not already in place. Research on modelling potential savings with split-fill prescribing, and into the acceptability of oncology drug repositories to Irish patients and clinicians is ongoing in Cork, and could be expanded nationally. The establishment of drug repositories required local legislative changes in many US states [97], and this is also likely to be necessary prior to the introduction of any schemes in Ireland.

Ireland is not unique in the challenges it faces, and Cortes et al. [98] have examined the global difficulties in accessing cancer medicines, including challenges that we are fortunate not to face, such as the marketing of substandard generics with limited regulatory oversight. They propose some of strategies that could be considered at an Irish or EU level, such as risk-sharing approaches or value-based pricing, or removing sales tax from all medicines. Oral medications are already VAT exempt; however, injectable products are not, which may increase financial toxicity and limit access for patients not covered by the drug payment scheme.

Ultimately while the methods discussed here may help optimise spending, as clinicians we must continue to advocate for appropriate allocation of budgetary resources, and remain mindful of what we prescribe, who we prescribe to, and when to stop prescribing.

References

Hofmarcher T, Ericson O, Lindgren P (2022) Comparator report on cancer in Ireland - disease burden, costs and access to medicines. IHE Report / IHE Rapport 2022:4, IHE - The Swedish Institute for Health Economics https://ihe.se/en/publicering/cancer-in-ireland-disease-burden-costs-and-access-to-medicines/

Iwase T, Shrimanker TV, Rodriguez-Bautista R et al (2021) Changes in overall survival over time for patients with de novo metastatic breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 13:2650. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13112650

Hofmarcher T, Lindgren P, Wilking N, Jönsson B (2020) The cost of cancer in Europe 2018. Eur J Cancer 129:41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.01.011

Chawla N (2022) Global Top 10 Cancer Drugs By Sales 2021. In: Biospace. https://www.biospace.com/article/global-top-10-cancer-drugs-by-sales-2021-/. Accessed 14 Mar 2023

National Centre for Pharmacoeconomics (2023) Cost effectiveness of nivolumab (Opdivo®) for the adjuvant treatment of adult patients with oesophageal, or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer who have residual pathologic disease following prior neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Dublin Available at https://www.ncpe.ie/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Nivolumab-21043-Technical-Summary.pdf. Accessed 31 Mar 24

HSE (2022) Complete list of high tech products. Available at https://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/pcrs/online-services/prescribablehightechmeds.pdf. Accessed 31 Mar 2024

Kelly D, Brady C, Sui J et al (2017) Cancer care costs and clinical trials. Ir Med J 110(4):557

Cancer Trials Ireland (2022) Economic benefits of cancer trials. https://www.cancertrials.ie/about-us/economic-benefits-of-cancer-trials/. Accessed 8 Apr 2023

Liniker E, Harrison M, Weaver JMJ et al (2013) Treatment costs associated with interventional cancer clinical trials conducted at a single UK institution over 2 years (2009–2010). Br J Cancer 109:2051–2057. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.495

García-Sánchez S, Collado-Borrell R, González-Haba E et al (2022) A new methodology to estimate drug cost avoidance in clinical trials: development and application. Front Oncol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.889575

D’Ambrosio F, De Feo G, Botti G et al (2020) Clinical trials and drug cost savings for Italian health service. BMC Health Serv Res 20:1089. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05928-6

Pascarella G, Capasso A, Nardone A et al (2019) Costs of clinical trials with anticancer biological agents in an Oncologic Italian Cancer Center using the activity-based costing methodology. PLoS ONE 14:e0210330. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210330

Morris PG, Kelly R, Horgan A et al (2007) Patterns of participation of patients in cancer clinical trials in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 176:153–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-007-0058-2

Kelly C, Smith M, Flynn S et al (2016) Accrual to cancer clinical trial. Ir Med J 109:436

Fountzilas E, Said R, Tsimberidou AM (2018) Expanded access to investigational drugs: balancing patient safety with potential therapeutic benefits. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 27:155–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2018.1430137

Iudicello A, Alberghini L, Benini G, Mosconi P (2016) Expanded Access Programme: looking for a common definition. Trials 17:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-1108-0

Balasubramanian G, Morampudi S, Chhabra P et al (2016) An overview of Compassionate Use Programs in the European Union member states. Intractable Rare Dis Res 5:244–254. https://doi.org/10.5582/irdr.2016.01054

Cronin T, Ronayne C, O’Donovan N et al (2023) The Impact of Expanded Access Programs for Systemic Anticancer Therapy in an Irish Cancer Centre. Ir J Med Sci

Jacobs I, Singh E, Sewell L et al (2016) Patient attitudes and understanding about biosimilars: an international cross-sectional survey. Patient Prefer Adherence. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S104891

European Medicines Agency (2022) Statement on the scientific rationale supporting interchangeability of biosimilar medicines in the EU (EMA/627319/2022) Available from https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/public-statement/statement-scientific-rationale-supporting-interchangeability-biosimilar-medicines-eu_en.pdf. Accessed 31 Mar 24

Lee S-M, Jung J-H, Suh D et al (2019) Budget impact of switching to biosimilar trastuzumab (CT-P6) for the treatment of breast cancer and gastric cancer in 28 European Countries. BioDrugs 33:423–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-019-00359-0

Triantafyllidi E, Triantafillidis JK (2022) Systematic review on the use of biosimilars of trastuzumab in HER2+ breast cancer. Biomedicines 10:2045. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10082045

Donnelly S (2022) Medicinal products: Dáil Éireann Debate, Tuesday - 22 March 2022 https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2022-03-22/1073/#pq_1073

Troein P, Newton M, Stoddart K, ARIAS A (2022) The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe. Available from https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-01/biosimilar_competition_en_0.pdf. Accessed 31 Mar 24

Hillhouse E, Mathurin K, Bibeau J et al (2022) The economic impact of originator-to-biosimilar non-medical switching in the real-world setting: a systematic literature review. Adv Ther 39:455–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-021-01951-z

Shubow S, Sun Q, Nguyen Phan AL et al (2023) Prescriber perspectives on biosimilar adoption and potential role of clinical pharmacology: a workshop summary. Clin Pharmacol Ther 113:37–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.2765

Bachu RD, Abou-Dahech M, Balaji S et al (2022) Oncology biosimilars: new developments and future directions. Cancer Rep. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnr2.1720

Rodriguez G, Mancuso J, Lyman GH et al (2023) ASCO policy statement on biosimilar and interchangeable products in oncology. JCO Oncol Pract. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.22.00783

Lam SW, Amoline K, Marcum C, Leonard M (2021) Healthcare system conversion to a biosimilar: trials and tribulations. Am J Heal Pharm. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/zxab279

Meriggi F, Zaniboni A (2020) ‘The same old story’: thoughts on authorized doses of anticancer drugs. Ther Adv Med Oncol 12:175883592090541. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758835920905412

Berek JS, Matulonis UA, Peen U et al (2018) Safety and dose modification for patients receiving niraparib. Ann Oncol 29:1784–1792. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy181

Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R et al (2015) Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 16:908–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00083-2

Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R et al (2015) Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 372:2018–2028. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1501824

Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim D-W et al (2016) Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 387:1540–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7

Freshwater T, Kondic A, Ahamadi M et al (2017) Evaluation of dosing strategy for pembrolizumab for oncology indications. J Immunother Cancer 5:43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-017-0242-5

Farooq AR, O’Brien T, O’Reilly S (2020) Is flat dosing cost-effective? Re: ‘the same old story’: thoughts on authorised doses of anticancer drugs. Ther Adv Med Oncol 12:175883592097420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758835920974203

European Medicines Agency (2020) Summary of Product Characteristics: KEYTRUDA 25 mg/mL concentrate for solution for infusion. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/keytruda-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 16 Mar 2023

European Medicines Agency (2020) Summary of Product Characteristics: OPDIVO 10 mg/mL concentrate for solution for infusion. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/opdivo-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 16 Mar 2023

NCCP (2018) NCCP regimen: pembrolizumab 200mg monotherapy. https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/5/cancer/profinfo/chemoprotocols/melanoma/455-pembrolizumab-200mg-monotherapy.pdf. Accessed 16 Mar 2023

Goldstein DA, Gordon N, Davidescu M et al (2017) A phamacoeconomic analysis of personalized dosing vs fixed dosing of pembrolizumab in firstline PD-L1-positive non–small cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx063

Sonbol MB, Mountjoy LJ, Firwana B et al (2020) The role of maintenance strategies in metastatic colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol 6:e194489. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.4489

Adams RA, Meade AM, Seymour MT et al (2011) Intermittent versus continuous oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine combination chemotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: results of the randomised phase 3 MRC COIN trial. Lancet Oncol 12:642–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70102-4

Adams R, Goey K, Chibaudel B et al (2021) Treatment breaks in first line treatment of advanced colorectal cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev 99:102226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2021.102226

Adams RA, Fisher DJ, Graham J et al (2021) Capecitabine versus active monitoring in stable or responding metastatic colorectal cancer after 16 weeks of first-line therapy: results of the randomized FOCUS4-N trial. J Clin Oncol 39:3693–3704. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.01436

Henderson RH, French D, McFerran E et al (2022) Spend less to achieve more: economic analysis of intermittent versus continuous cetuximab in KRAS wild-type patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Cancer Policy 33:100342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpo.2022.100342

Wasan H, Meade AM, Adams R et al (2014) Intermittent chemotherapy plus either intermittent or continuous cetuximab for first-line treatment of patients with KRAS wild-type advanced colorectal cancer (COIN-B): a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 15:631–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70106-8

Medical Independent (2019) Day wards ‘unable’ to accommodate cancer patients — NCCP. Med Indep. Available from https://www.medicalindependent.ie/in-the-news/latest-news/day-wards-unable-to-accommodate-cancer-patients-nccp/. Accessed 31 Mar 24

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2018) Pembrolizumab for untreated PD-L1-positive metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. Technology appraisal guidance [TA531]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta531/chapter/1-Recommendation. Accessed 16 Mar 2023

Coen O, Corrie P, Marshall H et al (2021) The DANTE trial protocol: a randomised phase III trial to evaluate the Duration of ANti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody Treatment in patients with metastatic mElanoma. BMC Cancer 21:761. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-021-08509-w

Marron TU, Ryan AE, Reddy SM et al (2021) Considerations for treatment duration in responders to immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Immunother Cancer 9:e001901. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2020-001901

Szmulewitz RZ, Peer CJ, Ibraheem A et al (2018) Prospective International Randomized Phase II Study of low-dose abiraterone with food versus standard dose abiraterone in castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 36:1389–1395. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4381

Patel A, Tannock IF, Srivastava P et al (2020) Low-dose abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer: is it practice changing? Facts and Facets. JCO Glob Oncol 6:382–386. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.19.00341

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2022) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Prostate Cancer. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed 15 Mar 2023

Ratain MJ, Cohen EE (2007) The value meal: how to save $1,700 per month or more on lapatinib. J Clin Oncol 25:3397–3398. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0758

Koch KM, Reddy NJ, Cohen RB et al (2009) Effects of food on the relative bioavailability of lapatinib in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 27:1191–1196. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3285

Xu F, Lee K, Xia W et al (2020) Administration of lapatinib with food increases its plasma concentration in Chinese patients with metastatic breast cancer: a prospective phase II study. Oncologist 25:e1286–e1291. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0044

Overbeek JK, ter Heine R, Verheul HMW et al (2023) Off-label, but on target: the evidence needed to implement alternative dosing regimens of anticancer drugs. ESMO Open 8:100749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100749

Lubberman FJE, Gelderblom H, Hamberg P et al (2019) The effect of using pazopanib with food vs. fasted on pharmacokinetics, patient safety, and preference (DIET Study). Clin Pharmacol Ther 106:1076–1082. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1515

Wright AA, Zhang B, Keating NL et al (2014) Associations between palliative chemotherapy and adult cancer patients’ end of life care and place of death: prospective cohort study. BMJ 348:g1219–g1219. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1219

Prigerson HG, Bao Y, Shah MA et al (2015) Chemotherapy use, performance status, and quality of life at the end of life. JAMA Oncol 1:778. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2378

Department of Health (Irish government) (2022) National Cancer Strategy 2017–2026 Key Performance Indicators: December 2021. Available from https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/f012d-national-cancer-strategy-2017-2026-implementation-report-2021/. Accessed 31 Mar 2024

Wallington M, Saxon EB, Bomb M et al (2016) 30-day mortality after systemic anticancer treatment for breast and lung cancer in England: a population-based, observational study. Lancet Oncol 17:1203–1216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30383-7

Department of Health (Irish government) (2017) National Cancer Strategy 2017–2026. Dublin. Available from https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/a89819-national-cancer-strategy-2017-2026/. Accessed 31 Mar 24

Jewitt N, Rapoport A, Gupta A et al (2023) The effect of specialized palliative care on end-of-life care intensity in AYAs with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 65:222–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.11.013

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733–742. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1000678

Mallett V, Linehan A, Burke O et al (2021) A multicenter retrospective review of systemic anti-cancer treatment and palliative care provided to solid tumor oncology patients in the 12 weeks preceding death in Ireland. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 38:1404–1408. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909120985234

O’Sullivan H, Conroy M, Power D et al (2022) Immune checkpoint inhibitors and palliative care at the end of life: an Irish multicentre retrospective study. J Palliat Care 082585972210783. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/08258597221078391

Seow H, Barbera LC, McGrail K et al (2022) Effect of early palliative care on end-of-life health care costs: a population-based, propensity score–matched cohort study. JCO Oncol Pract 18:e183–e192. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.21.00299

Davis MP, Vanenkevort EA, Elder A et al (2023) The financial impact of palliative care and aggressive cancer care on end-of-life health care costs. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 40:52–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091221098062

Tie J, Cohen JD, Lahouel K et al (2022) Circulating tumor DNA analysis guiding adjuvant therapy in stage II colon cancer. N Engl J Med 386:2261–2272. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2200075

Zhou C, Das Thakur M, Srivastava MK et al (2021) 2O IMpower010: biomarkers of disease-free survival (DFS) in a phase III study of atezolizumab (atezo) vs best supportive care (BSC) after adjuvant chemotherapy in stage IB-IIIA NSCLC. Ann Oncol 32:S1374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2021.10.018

Hess LM, Cui ZL, Li XI et al (2018) Drug wastage and costs to the healthcare system in the care of patients with non-small cell lung cancer in the United States. J Med Econ 21:755–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2018.1467918

Bach PB, Conti RM, Muller RJ et al (2016) Overspending driven by oversized single dose vials of cancer drugs. BMJ 352

Leung CYW, Cheung MC, Charbonneau LF et al (2017) Financial impact of cancer drug wastage and potential cost savings from mitigation strategies. J Oncol Pract 13:e646–e652. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2017.022905

United States Pharmacopoeia (2022) General Chapter 797 Pharmaceutical Compounding – Sterile Preparations. USP-NF 2023:1

Fasola G, Aprile G, Marini L et al (2014) Drug waste minimization as an effective strategy of cost-containment in Oncology. BMC Health Serv Res 14:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-57

Ho KV, Edwards MS, Solimando DA Jr, Johnson AD (2016) Determination of extended sterility for single-use vials using the phaseal closed-system transfer device. J Hematol Oncol Pharm 6(2):46–50

Edwards MS, Solimando DA, Grollman FR et al (2013) Cost savings realized by use of the PhaSeal® closed-system transfer device for preparation of antineoplastic agents. J Oncol Pharm Pract 19:338–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078155213499387

Scully P, Garvey E (2012) Aseptic compounding practice in Ireland – how are we doing it? In: Conf. poster. http://hdl.handle.net/10147/244997. Accessed 31 Mar 24

Staskon FC, Kirkham HS, Pfeifer A, Miller RT (2019) Estimated cost and savings in a patient management program for oral oncology medications: impact of a split-fill component. J Oncol Pract 15:e856–e862. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.19.00069

Khandelwal N, Duncan I, Ahmed T et al (2011) Impact of clinical oral chemotherapy program on wastage and hospitalizations. J Oncol Pract 7:e25s–e29s. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2011.000301

Monga V, Meyer C, Vakiner B, Clamon G (2019) Financial impact of oral chemotherapy wastage on society and the patient. J Oncol Pharm Pract 25:824–830. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078155218762596

Dürr P, Schlichtig K, Krebs S et al (2022) Ökonomische Aspekte bei der Versorgung von Patient*innen mit neuen oralen Tumortherapeutika: Erkenntnisse aus der AMBORA-Studie. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 169:84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2022.01.002

Bekker CL, Melis EJ, Egberts ACG et al (2019) Quantity and economic value of unused oral anti-cancer and biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs among outpatient pharmacy patients who discontinue therapy. Res Soc Adm Pharm 15:100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.03.064

Stanz L, Ulbrich T, Yucebay F, Kennerly-Shah J (2021) Development and Implementation of an Oral Oncology Drug Repository Program. JCO Oncol Pract 17:e426–e432. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.20.00513

American Society for Clinical Oncology (2022) ASCO Position Statement on drug repository programs. Revised on October 21, 2022. https://old-prod.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/advocacy-and-policy/documents/2022-Drug-Repository-Statement.pdf. Accessed 19 Feb 2023

Smale EM, van den Bemt BJF, Heerdink ER et al (2023) Cost savings and waste reduction through redispensing unused oral anticancer drugs. JAMA Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.4865

Bekker C, van den Bemt B, Egberts TC et al (2019) Willingness of patients to use unused medication returned to the pharmacy by another patient: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 9:e024767. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024767

Alhamad H, Donyai P (2020) Intentions to “reuse” medication in the future modelled and measured using the theory of planned behavior. Pharmacy 8:213. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8040213

Smale EM, Egberts TCG, Heerdink ER et al (2022) Key factors underlying the willingness of patients with cancer to participate in medication redispensing. Res Soc Adm Pharm 18:3329–3337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.12.004

Young S, Zigmond M, Lee S (2015) Evaluating the effects of a 14-day oral chemotherapy dispensing protocol on adherence, toxicity, and cost. J Hematol Oncol Pharm 5:75–80

Dalal AA, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, Burne R et al (2018) Dosing patterns and economic burden of palbociclib drug wastage in HR+/HER2− metastatic breast cancer. Adv Ther 35:768–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0701-5

Biskupiak J, Oderda G, Brixner D et al (2019) Quantification of economic impact of drug wastage in oral oncology medications: comparison of 3 methods using palbociclib and ribociclib in advanced or metastatic breast cancer. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 25:859–866. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.8.859

Li N, Du EX, Chu L et al (2017) Real-world palbociclib dosing patterns and implications for drug costs in the treatment of HR+/HER2- metastatic breast cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother 18:1167–1178. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2017.1351947

Duggan B, Smith A, Barry M (2021) Uptake of biosimilars for TNF-α inhibitors adalimumab and etanercept following the best-value biological medicine initiative in Ireland. Int J Clin Pharm 43:1251–1256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01243-0

Lichter AS (2018) From choosing wisely to using wisely: increasing the value of cancer care through clinical research. J Clin Oncol 36:1387–1388. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.78.4264

Briones N (2020) Current state of drug recycling programs in the United States. University of Chicago Law School, Int Immers Progr Pap. Available from https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/international_immersion_program_papers/121. Accessed 31 Mar 24

Cortes J, Perez-García JM, Llombart-Cussac A et al (2020) Enhancing global access to cancer medicines. CA Cancer J Clin 70:105–124. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21597

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium Health Research Board grant (UCC Cancer Trials Group, CTIC-2021–002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to research, manuscript writing, and manuscript editing. All authors have approved this manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not required (literature review only); no other ethical issues raised.

Conflict of interest

MH is a Breakthrough Cancer Fellowship Recipient. TC is a Breakthrough Cancer Summer Student Grant recipient. Educational sponsorship received from Jansen, MSD, Novartis.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kieran, R., Hennessy, M., Coakley, K. et al. Optimising oncology drug expenditure in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-024-03672-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-024-03672-y