Abstract

Purpose

Nonossifying fibromas (NOFs) present in a characteristic pattern in the distal tibia. Their predilection to this region and etiology remain imprecisely defined.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients between January 2003 and March 2014 for distal tibial NOFs. We then reviewed radiographs (XRs), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for specific lesion characteristics.

Results

We identified 48 distal tibia NOFs in 47 patients (31 male, 16 female; mean age 12.3 years, range 6.9–17.8). This was the second most common location in our population (30 % of NOFs), behind the distal femur (42 %). Thirty-four lesions had CT and nine had MRI. Thirty-one percent were diagnosed by pathologic fracture. Ninety-six percent of lesions were located characteristically in the distal lateral tibia by plain radiograph, in direct communication with the distal extent of the interosseous membrane on 33 of the 34 (97 %) lesions with CT available for review and all nine (100 %) with MRI. The remaining two lesions occurred directly posterior.

Conclusions

The vast majority of distal tibial NOFs occur in a distinct anatomic location at the distal extent of the interosseous membrane, which may have etiologic implications.

Level of evidence

IV (case series).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Originally described in detail in 1942 by Jaffe and Lichtenstein, nonossifying fibromas (NOFs) are the most common benign lesion of bone seen in children [1–4]. They possess a characteristic radiographic (XR) appearance of radiolucent, eccentric, cortically based lesions with an internally bubbly appearance and sclerotic margins. Histologic findings consist of fibroblastic cells in a storiform pattern. Their natural history is gradual ossification and resolution with skeletal maturity [3]. However, little remains known about the etiology of these lesions [5].

The purpose of the present study was to characterize a large cohort of patients with NOFs isolated to the distal tibia by XR, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We empirically noted a predilection of these lesions to a characteristic location in the distal lateral tibia and predicted that such a pattern may emerge in a large series. Our aim was to further describe this anatomy with advanced imaging.

Materials and methods

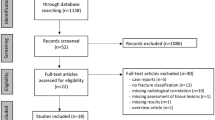

Institutional review board approval was sought and obtained. A retrospective chart review was performed on patients seen at Rady Children’s Hospital in San Diego between January 2003 and March 2014. Charts were queried for ICD-9 codes consistent with NOF and/or CPT codes consistent with curettage/grafting of bone lesion. These were then reviewed in detail for those with a diagnosis of distal tibia NOF (either by radiographic or histologic findings). Patients who did not have imaging available for review were excluded. No other exclusion criteria were employed. Charts were reviewed for patient demographics. Study patients were grouped by those diagnosed incidentally and those diagnosed by pathologic fracture. In the absence of pathologic fracture, lesions were characterized as “incidental” regardless of the presence or absence of pain, as this was not reliably elucidated in our retrospective chart review.

Radiographs from the time of diagnosis were reviewed for the presence and location of NOF. Lesions of the distal tibia radiographically consistent with NOF were included regardless of size. CT or MRI scans had also been performed around the time of diagnosis to further evaluate the lesion. These were reviewed to further characterize the relationship with surrounding soft tissue structures.

Results

Our query yielded 161 NOFs. Figure 1 demonstrates their anatomic distribution. Forty-eight lesions in 47 patients localized to the distal tibia. There was a male predilection (66 %) and the average age at initial XR was 12.3 years (range 6.9–17.8). Thirty-one presented with a pathologic fracture at the time of diagnosis. Radiographs were available for all patients, with 46 (96 %) lesions localizing to the distal and lateral aspect of the tibia, proximal to the physis (Fig. 2). The remaining two localized directly posteriorly at approximately the same height distally.

Thirty-four (71 %) patients had a CT scan available for review. Direct communication with the distal extent of the interosseous membrane was seen on 33 (97 %) lesions (Figs. 3 and 4), with the exception being the one of the two aforementioned posteriorly based lesions for which we had CT (Fig. 5). Cortical breach was noted in 28 scans. This breach localized to the interosseous membrane attachment on all except for the one posteriorly localized lesion. Nine (19 %) patients had an MRI available for review, and all showed continuity of the distal extent of the interosseous membrane with the distal, lateral extent of the NOF (Fig. 6).

Discussion

The etiology of NOFs remains poorly understood, with predominant competing theories being that they arise either from bone marrow cell lineage or from a disturbance of the physis itself given their characteristic growth away from this structure [1, 5, 6]. The present study shows an eccentric localization of distal tibia lesions to the lateral metaphysis and a common relationship with the distal extent of the interosseous membrane on advanced imaging. The relationship between fibrous metaphyseal defects and the insertion of tendons and ligaments has been previously described by Ritschl et al. in 1988, though without the benefit of MRI confirmation [7]. While this association alone does not prove an etiologic relationship, we propose that the traction of the interosseous membrane could account for this localization in children. A similar process has been described in other lesions, such as distal femoral cortical irregularities localizing to the medial gastrocnemius origin on MRI, theoretically resulting from traction here during the relatively rapid growth of the posteromedial region of the distal femoral physis [8, 9].

Furthermore, there is a normal and well-described distal migration of the fibula relative to the tibia with growth of the pediatric ankle. This differential distal migration of the fibula to the tibia does not occur in children with a tibiofibular synostosis [10]. Such differential growth rates may provide traction on the interosseous ligament from fibular migration, contributing to NOF development. Alternatively, either longitudinal “pistoning” or the known external rotation of the fibula with respect to the tibia during normal gait may generate such traction. Interestingly, while not the focus of the current study, we have also encountered NOFs of the distal fibula, which, on MRI, can communicate directly with the distal extent of the interosseous membrane (Fig. 7), suggesting that such a process may affect either end of this structure. The two posteriorly localized lesions clearly show no relationship to the interosseous membrane (Fig. 5). Unfortunately, no MRI was available for review in either case, so precise soft tissue attachments could not be defined. One could theorize that an alternative structure (such as the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament) may explain these variants.

The strength of the present series is in its inclusion of a large number of NOFs and a precise characterization of these lesions with advanced imaging. Nearly all NOFs were in a discrete location in the distal tibia and the size varied from 1 cm to very large, over 6 cm. We confirmed a male predilection of 2:1, as has been previously reported, but are unaware of a pathophysiologic explanation for such an observation [3, 5]. The retrospective nature of this series assumes all the limitations inherent to such a design. However, a wide spectrum of lesions were identified, from very small to very large (Fig. 3), and we, therefore, believe that a relatively representative spectrum of the disease was captured. Additionally, retrospective study in this case is unlikely to have introduced any bias with regards to the anatomic description of these lesions. In conclusion, the eccentric lateral localization of distal tibia NOFs and their anatomic relationship with the distal extent of the interosseous membrane may provide clues to the as yet undefined etiology of these lesions.

References

Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L (1942) Non-osteogenic fibroma of bone. Am J Pathol 18:205–221

Caffey J (1955) On fibrous defects in cortical walls of growing tubular bones: their radiologic appearance, structure, prevalence, natural course, and diagnostic significance. Adv Pediatr 7:13–51

Betsy M, Kupersmith LM, Springfield DS (2004) Metaphyseal fibrous defects. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 12:89–95

De Mattos CBF, Binitie O, Dormans JP (2012) Pathological fractures in children. Bone Joint Res 1:272–280

Hatcher CH (1945) The pathogenesis of localized fibrous lesions in the metaphyses of long bones. Ann Surg 122:1016–1030

Cunningham JB, Ackerman LV (1956) Metaphyseal fibrous defects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 38-A:797–808

Ritschl P, Karnel F, Hajek P (1988) Fibrous metaphyseal defects—determination of their origin and natural history using a radiomorphological study. Skeletal Radiol 17:8–15

Suh JS, Cho JH, Shin KH et al (1996) MR appearance of distal femoral cortical irregularity (cortical desmoid). J Comput Assist Tomogr 20:328–332

Vieira RL, Bencardino JT, Rosenberg ZS et al (2011) MRI features of cortical desmoid in acute knee trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 196:424–428

Frick SL, Shoemaker S, Mubarak SJ (2001) Altered fibular growth patterns after tibiofibular synostosis in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83:247–254

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

None of the authors have conflicts of interest pertinent to this article. No funding was received for this article. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was sought and obtained. The IRB found that this study satisfies the criteria for granting a waiver of consent; therefore, no consent was sought by subjects in this retrospective review study. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Funding source

None of the authors received financial support for this study. Dr. Mubarak has stock in Rhino Pediatric Orthopedic Designs.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Study conducted at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA, USA.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Muzykewicz, D.A., Goldin, A., Lopreiato, N. et al. Nonossifying fibromas of the distal tibia: possible etiologic relationship to the interosseous membrane. J Child Orthop 10, 353–358 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11832-016-0745-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11832-016-0745-5