Abstract

People suffering from chronic insomnia are at an increased risk of physical and mental illness. The absenteeism rate for people with sleep disorders in Germany is more than twice as high as for people without. Therefore, appropriate diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders is a considerable medical and social necessity.

The aim of this prospectively planned analysis is to describe self-reported effects of insomnia in everyday life and the current medical treatment situation in Germany.

Data from a demographically representative sample of adults from the German participants in the National Health and Wellness Survey 2020 (N = 10,034) were analysed. Information was collected from respondents who reported insomnia confirmed by a physician (n = 532). The severity of insomnia at the time of the interview was assessed using the Insomnia Severity Index. Health status and quality of life were assessed using EQ-5D and SF-36, and work productivity and work impairment using the Work Productivity and Activity Impact Questionnaire.

The median duration of illness was 5 years. About 50% of the respondents reported moderate to severe insomnia. Around 70% of those affected had never taken a prescription medication for their insomnia, and most of them said that they had never been recommended a prescription medication by a physician to treat their sleep disorder. Their health status, self-reported morbidity and quality of life were impaired compared with the general population.

People with insomnia have worse health than those without insomnia. A significant proportion of those affected are currently not offered prescription medication. Even if the reasons for this lack of care cannot be clearly determined based on self-reported information, the data indicate an inadequate and relevant care deficit for chronic insomnia in Germany.

Zusammenfassung

Menschen, die unter chronischer Insomnie leiden, haben ein erhöhtes Risiko für körperliche und psychische Erkrankungen. Die Fehlzeitenquote ist bei Personen mit Schlafstörungen in Deutschland mehr als doppelt so hoch wie bei Personen ohne. Daher ist eine angemessene Diagnose und Therapie von Schlafstörungen eine wesentliche medizinische und gesellschaftliche Notwendigkeit.

Ziel dieser prospektiv geplanten Analyse ist die Beschreibung von Selbstauskünften zu Auswirkungen der Insomnie im Alltag und der derzeitigen medikamentösen Behandlungssituation in Deutschland.

Es wurden Daten einer demografisch repräsentativen Stichprobe von Erwachsenen der deutschen Teilnehmenden an der Nationalen Gesundheits- und Wellness Survey 2020 (N = 10.034) analysiert. Informationen von Befragten, die eine seitens einer ärztlichen Fachperson bestätigte Insomnie angaben (N = 532), wurden erfasst. Der Schweregrad der Insomnie zum Zeitpunkt der Befragung wurde mit dem Insomnia-Severity-Index (ISI) ermittelt. Gesundheitszustand und Lebensqualität wurden mittels EQ-5D und SF-36, Arbeitsproduktivität und Arbeitsbeeinträchtigung mittels WPAI erhoben.

Die Krankheitsdauer betrug im Median 5 Jahre. Circa 50 % der Befragten gaben eine mittelschwere bis schwere Insomnie an. Circa 70 % der Betroffenen hatte noch nie ein verschriebenes Medikament gegen ihre Insomnie eingenommen, und die meisten von ihnen gaben an, ärztlicherseits noch nie ein verschreibungspflichtiges Medikament zur Behandlung ihrer Schlafstörung empfohlen bekommen zu haben. Gesundheitszustand, selbstberichtete Morbidität und Lebensqualität der Betroffenen waren im Vergleich zur Allgemeinbevölkerung beeinträchtigt.

Personen mit Insomnie weisen einen schlechteren Gesundheitszustand als solche ohne Insomnie auf. Einem erheblichen Anteil der Betroffenen werden derzeit keine verschreibungspflichtigen Medikamente zur Behandlung angeboten. Auch wenn sich die Gründe für diese Unterversorgung anhand der Selbstauskünfte nicht eindeutig ermitteln lassen, weisen die Daten auf eine inadäquate und relevante Versorgungslücke bei chronischer Insomnie in Deutschland hin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction to the topic

Insomnia is often a chronic disease. Patients suffer from impaired health, which has an impact on their working life (e.g., increased absence due to illness). Specific treatments consist of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) or drug therapy, which, in Germany, until now, could be regularly prescribed for a maximum duration of 4 weeks. For chronic insomnia, no primary causal or symptomatic treatment other than CBT‑I has been available so far. This analysis provides important insights into the current care situation for chronic insomnia in Germany.

Introduction

Insomnia is defined as a disorder of sleep onset and/or sleep maintenance that is not due to environmental factors or self-induced sleep deprivation, and which manifests during the day with mental fatigue, depression, general malaise, or cognitive impairment [29].

Epidemiological data show considerable individual (increased risk of almost every disease) as well as socioeconomic burdens (absence from work, early retirement, general health costs–the burden of disease) [1, 12,13,14, 17, 21, 23, 27, 29, 30].

When the distinction between primary and secondary insomnia was abolished in 2013, sleep disorders (insomnia) were classified as an independent disorder for the first time in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [1]. The definition was adopted in both the third edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) [24] and the currently effective 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) [5], which is also due to be introduced in Germany in 2027/2028. Insomnia according to the accepted DSM‑5 definition is, however, not included in the former but still used ICD-10 German modification (ICD-10-GM).

Around 6% of adults in Germany suffer from insomnia [29]. In addition to inadequate sleep quantity and/or quality, insomnia is characterized by impaired cognition, mood swings, mental fatigue, and impaired daytime functioning, and is associated with negative consequences for the patient’s functioning, health, and quality of life [2]. A distinction is made between acute insomnia (coded as 7A01 according to ICD-11) and chronic insomnia (ICD-11 7A00) [5]. Chronic insomnia also has a negative impact on socioeconomics, e.g., patients are more than twice as likely to be absent from work than people with normal sleep [17, 27]. Chronic insomnia can only be categorized in ICD-10 as F51.0 [5]. This appears questionable from the perspective of sleep medicine, as the ICD is currently used as a key code for all billable services in outpatient care in Germany and serves as the basis for the German diagnosis-related groups (G-DRG) system in inpatient care. It is also used as the basis for mortality statistics [5] and as a data source for health reporting [8, 9]. In 2019, 1881 people with a main diagnosis of F51.0 were hospitalized in Germany ([8]; Fig. 1).

Insomnia has a multifactorial pathogenesis [20, 29]. In addition to predisposing, e.g., genetic, neurological, and personal factors, precipitating and perpetuating factors are responsible for development of the disorder, which lead to an imbalance in sleep–wake regulation caused by overactivity of the arousal systems and/or hypoactivity of the sleep-inducing systems [20, 29].

The German guideline for diagnosis and treatment of insomnia recommends cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) as the first treatment option [29]. Due to the limited nationwide availability of structured CBT‑I, this was only carried out in around 10% of those affected in Germany before the introduction of digital health applications (DiGA) [27]. According to clinical experience, sleep hygiene measures, relaxation techniques, and other components of behavioral therapy are regularly taught by doctors and are also used by many patients, but there are no published data on this. Only if CBT‑I is not available, not an option, or is not effective, should the condition be treated pharmacologically [29]. The hypnotics approved for short-term treatment (benzodiazepines and Z‑substances) can cause severe side effects, including hangover effects, nocturnal confusion, falls, and rebound sleep disorders, as well as tolerance and dependence [18, 22, 26, 29,30,31]. In elderly people, there is the additional problem of drug–drug interactions due to concomitant illnesses and the associated polypharmacy [26, 29]. Furthermore, there is a potential risk of inadequate medication in the elderly according to PRISCUS, which should be avoided [26]. Pharmacological treatments that can treat the root cause or relieve symptoms in the long term have not yet been offered to people with chronic insomnia in particular, because such medications that can be regularly prescribed for chronic insomnia are not available in Germany [29]. Medications that are not even approved for the treatment of insomnia are therefore often used off-label [29]. The benzodiazepines and Z‑drugs that can currently be prescribed are generally only authorized for short-term treatment and should generally be discontinued within 4 weeks. In practice, structured support should be provided during this time, e.g., by means of CBT‑I or digital health applications [30, 32].

The aim of this analysis is to present the effects of insomnia on everyday life and the current drug treatment landscape. It is based on the analyzed data from the German cohort of a representative cross-sectional survey conducted in 2020 as part of the National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS), based on self-reports from affected individuals who stated that they had been diagnosed with insomnia [6].

Methods

Study design

This is a prospectively planned subgroup analysis of self-reported data from participants in an online survey. Respondents from Germany who stated that they had been diagnosed with insomnia and had no other sleep disorder were included in the analysis.

Data source

Data from the NHWS survey conducted in 2020 form the basis of the evaluation. The 2020 Europe NHWS protocol was reviewed by the Pearl Institutional Review Board (Indianapolis, IN, USA; 19-KANT-204) [6].

The NHWS is an annual, global, online cross-sectional survey in which a demographically representative sample of adults (≥ 18 years) is interviewed. Respondents are identified via a web-based consumer panel, i.e., a pre-recruited sample of adults who agree to participate in a survey. The survey is conducted in the US, Europe, and Asia and includes 35 validated scales and disease-specific assessment measures [6].

The present subgroup analysis included information from respondents in Germany with a diagnosis of insomnia who had no other form of sleep disorder and who were treated or not treated with prescription medication for their insomnia.

Participants for the subgroup analysis were identified on the basis of the following general question asked as part of the NHWS: Which of the following illnesses have you had in the past 12 months?

Data from identified individuals who met the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used for the analysis:

Inclusion criterion.

Self-disclosure of a confirmed diagnosis of insomnia in the past 12 months.

Exclusion criteria.

-

Self-reported narcolepsy, sleep apnea, or other sleep disorder.

-

Self-reported other serious illness (e.g., cancer, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, chronic liver disease, liver cirrhosis, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease).

-

Pregnancy.

The main objective was to determine pharmacological treatment of insomnia and the impact of insomnia on the health status, quality of life, and work productivity of people who reported a confirmed diagnosis of insomnia and received treatment or no treatment for this condition. Health status data were collected using the standardized and validated EuroQoL-5-Dimensions (EQ-5D-5L) [25] and Short Form 36 (SF-36) [11] questionnaires. Patient-reported morbidity and quality of life were recorded using the SF-36, while work productivity and work impairment were recorded using the Work Productivity and Activity Impact Questionnaire (WPAI) [28].

In addition to demographic and disease-specific data, self-reported data on the clinical, social, and emotional impact of insomnia as well as the burden of illness and treatment-related unmet needs were collected [7]. The severity of the illness was measured using the validated Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) instrument [10]. The higher the score, the more severe the insomnia: 0 to 7 points: no sleep disturbance; 8 to 14 points: sub-threshold sleep disturbance; 15 to 21 points: moderate sleep disturbance; 22 to 28 points: severe sleep disturbance [10].

For the insomnia-specific analysis, the participants were divided into two cohorts:

-

DT cohort: self-report of a medical diagnosis of insomnia (“D” = diagnosed) and treatment with prescription medication (“T” = treated).

-

DUt cohort: self-report of a medical diagnosis of insomnia (“D” = diagnosed) and no treatment with prescription medication (“Ut” = untreated).

In order to obtain a representative sample of the adult population, a stratified randomization method was used according to gender, ethnicity, and age [6].

Statistics

The database was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and/or R 3.6.0 or higher (R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Number (N), percentages, and mean with standard deviation or median with 25 and 75 percentiles are given. The questionnaires were analyzed according to the respective manuals [6, 11, 25].

The chi2 test was used for group comparisons calculated for the categorical data between the DT and DUt cohorts as well as insomnia cohorts vs. total cohort excluding insomnia cohorts. The significance level was specified as 0.05. R 4.3.1 was used for this.

Results

Study population

From the data of 10,034 adults from Germany, a total of 532 (5.3%) participants were identified who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 2). The participants were divided into two cohorts:

-

DT cohort: N = 138 (25.9%).

-

DUt cohort: N = 394 (74.1%).

Within the DUt cohort, 71.8% (283/394) of people who reported a medically confirmed diagnosis of insomnia stated that they had never taken prescription medication. Of these, only 15.9% (45/283) reported that they had ever been offered a prescription medication by a physician.

Sociodemographic and health-related data

The sociodemographic and health-related data are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Mean age was 52 years (DT cohort; standard deviation [SD] 14 years) and 48 years (DUt; SD 16 years), the majority were female (DT, 55.1%; DUt, 63.2%) and had never smoked (DT, 39.1%; DUt, 41.1%). With regard to alcohol consumption, 28.3% (DT) and 29.9% (DUt) reported no drinking, 62.3% (DT) and 63.7% (DUt) up to four times a week, and 9.4% (DT) and 6.3% (DUt) more than four times a week.

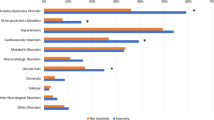

With regard to comorbidities, 39.1% of the DT cohort and 38.3% of the DUt cohort reported at least one comorbidity. Among the comorbidities, pain conditions were the most common (two thirds in both cohorts), followed by depression (55.8% DT, 49.2% DUt; Table 3). In the total population of respondents, the rate of comorbidities was 20.1%.

Self-reported data on insomnia

The majority of diagnoses of insomnia were made by general practitioners or internal medicine specialists (DT, 54.3%; DUt, 60.7%). The diagnosis was made by psychiatric specialists almost twice as often in the DT cohort as in the DUt cohort: 31.2% vs. 18.3% (Table 4).

The median reported duration of insomnia since medical diagnosis was 5.5 years (25% 2 years, 75% 11 years; DT cohort) and 5.0 years (25% 2 years, 75% 10 years; DUt cohort). The participants reported a median of 290 days (25% 110 days years, 75% 360 days; DT cohort) or 180 days (25% 63 days, 75% 360 days; DUt cohort) of sleep disturbance in the past 12 months (Table 4).

Of those treated, 36% (49/138) of the DT cohort were treated with benzodiazepines (B) or benzodiazepine receptor agonists (Z-drugs; Z), 70% (97/138) with non-B/non‑Z and/or off-label medications (in relation to the sleep disorder), e.g., sleep-inducing antidepressants. On average (±SD), B and Z medications were taken for 42 (±64) and 45 (±38) months, respectively. Most patients in the DT cohort were currently taking Z‑drugs (n = 36) and sedative antidepressants (n = 31, of whom 16 were taking mirtazapine and 11 amitriptyline). In the DT cohort, sedative antidepressants and Z‑drugs were taken for the longest, on average 49.8 (±73.8) and 44.9 (±37.5) months respectively. Looking only at the previous month, sedative antidepressants were used the longest, on average for 22.6 (±10.9) days, followed by melatonin receptor agonists for 17.8 (±12.8) days (Table 4).

A total of 72% (283/394) of the DUt cohort had never taken a prescription medication for their insomnia. Only 16% (45/283) of these DUt subjects stated that they had ever been offered a prescription medication for insomnia treatment by a physician (Table 4).

At the time of the online survey, 46% of the DT cohort and 50% of the DUt cohort had no or sub-threshold insomnia, 36% of the DT cohort and 39% of the DUt cohort had moderate insomnia, and 19% of the DT cohort and 11% of the DUt cohort had severe insomnia according to the ISI (Fig. 3). The mean ISI score (or median) was 15.6 (15.0) and 14.7 (14.5) in the DT and DUt cohorts, respectively (Table 4).

Proportion and distribution of clinically manifested (ISI ≥ 15 [10], i.e., moderate or severe) self-reported insomnia according to ISI at the time of the survey (recall period 1 month); DT diagnosed and treated, DUt diagnosed and untreated, ISI Insomnia Severity Index

Effects of insomnia

In the DT cohort, 15.2% reported severe effects of the sleep disorder on their private and professional lives when they were on medication. This percentage was 48.8% in the DT cohort if they were not to take medication. In the DUt cohort, in which no medication was regularly taken, 14.5% reported severe effects of the sleep disorder on their private and professional lives (Table 5).

With regard to the diagnosis of a “sleep disorder” by the respective medical specialties (general medicine/internal medicine/psychiatry/sleep medicine/others), the difference between the DT cohort and the DUt cohort is significant (chi2 = 13.9140; p = 0.0030; Table 4). The insomnia cohorts differed significantly from the non-insomnia cohort in terms of comorbidities (Table 3; p-values < 0.0001). In addition, both insomnia cohorts were in significantly worse health than the total of all NHWS participants, regardless of the questionnaire used or the health aspects surveyed (Table 6). People in the DUt cohort had slightly higher scores overall than those in the DT cohort. For the EQ-5D, there was a mean value of 0.88 for all vs. 0.73 and 0.76 for the DT and DUt cohorts respectively, with 1 representing the best and 0 the worst conceivable state of health. For the SF-6D utility score, the mean value for all was 0.74 vs. 0.61 for the DT cohort and 0.62 for the DUt cohort (Table 6). For the SF-36, the values of all scales for both insomnia cohorts were significantly lower than those for all participants in the survey. In particular, the mental sum component of the SF-36 appears to be significantly lower than the German reference values for people with at least one comorbidity (49.3) at 40.7 (DT) and 40.9 (DUt) [11].

Employees in the DT cohort and the DUt cohort had missed an average of 27% (±36) and 16% (±28) of working hours during the past 7 working days for health reasons, while this applied to an average of 9% (±22) of the total respondents. The percentage of impairment at work due to health was 38% on average in both insomnia cohorts and was thus twice as high as among the overall respondents (19% on average). Impairment of overall work productivity and normal daily activity was reported on average by 43% (±32) and 50% (±29) of the DT cohort and 42% (±28) and 46% (±27) of the DUt cohort. This compares to an average of 22% (±28) and 23% (±27) reported corresponding impairments in the total respondents.

Discussion

The analysis carried out here to assess the pharmacological treatment and health status of people with insomnia in Germany shows that with a median duration of illness of 5 years, around 50% of those affected suffered from moderate to severe insomnia and only 30% of those affected took a prescription medication to treat their insomnia or had even been offered this at all. The state of health, self-reported morbidity, and quality of life were described as limited by those affected by insomnia.

The data of the NHWS 2020 participants from Germany included in this study are based on non-verified self-reports. The focus was on people who stated in the survey that they had been diagnosed with insomnia by a physician. This was around 5% of the total respondents, which is roughly in line with previous data on the prevalence of insomnia in Germany [21, 29]. The participants with insomnia had been suffering from their condition for several years and, therefore, their condition can be interpreted as chronic insomnia [1, 24]. The duration of the illness coincides with the often long waiting time until first consultation with a specialist [13]. The proportion of adults suffering from insomnia with at least moderate insomnia according to the ISI [10] was around 50%. However, it is not possible to determine with certainty from the available data how many participants had acute insomnia vs. chronic insomnia [1, 5, 24]. Current estimates based on the best available evidence assume approximately 8332–219,413 people with chronic insomnia in Germany [15, 23]. The wide range of estimates is due to the fact that the data sources are difficult to objectify. Only figures from coding databases can be used as a basis for these estimates, in this specific case, data from SHI-insured persons. At present, only ICD-10-GM F51.0 can be used for coding [5]. F51.0 is currently the only ICD-10-GM code that also reflects a chronic form of insomnia [5]. In addition, reports of incapacity to work in people with any form of insomnia were used for these calculations [15, 23, 27]. However, due to the vagueness of previous coding and the use of indirect indicators, it can be assumed that the number of people with chronic insomnia requiring treatment has socioeconomic relevance.

According to the literature, around 30% of people with insomnia are treated with medication [15, 23]. These figures are confirmed by the data presented here. Overall, between 2,000 and 79,000 people with chronic insomnia are currently being treated with medication in Germany [15].

According to current data, around 50% of people with insomnia also suffer from comorbidities. Chronic insomnia, which can occur comorbidly with depression, for example, is currently not represented at all in ICD-10 [5]. This shortcoming will be rectified in ICD-11, which has been effective internationally since 1 January 2022 [5]. In ICD-11, chronic insomnia is coded in its own chapter of sleep–wake disorders under 7A00 [5], thus considering chronic insomnia as an independent disorder in its own right.

The data collected also allow the conclusion to be drawn that the health status and quality of life of people with sleep disorders in Germany is impaired compared to the general population, which has also been published in earlier studies [21]. While the summarized values of the physical (for self-reported morbidities) and mental (for quality of life) sum components of the SF-36 for all 10,034 NHWS participants correspond to the German reference values of 50 each [11], these values are lower for the German insomnia cohort as a whole at approximately 44 (for self-reported morbidity) and 41 (for quality of life) [11]. This indicates considerable physical and psychosocial impairments and suggests a need for action in the management of insomnia.

In both cohorts, over 50% of the insomnia diagnoses were made in the area of general and internal medicine. However, the difference in the type of medical specialty that diagnosed the “sleep disorder” is statistically significant between the DT cohort and the DUt cohort (chi2 = 13.9140; p = 0.0030; Table 4). In the DT cohort, psychiatric specialists diagnosed the sleep disorder about twice as often as in the DUt cohort. Even if it is not known whether the medical discipline making the diagnosis is also the prescribing discipline, one reason for this could be the restriction on the prescription of hypnotics in accordance with No. 32 Annex III of the German Medicines Directive (AM-RL). Since the aim of the AM-RL is to prevent medicalization, the data support the weight of this guideline. However, diagnoses by different medical specialties must be comparable in terms of assessment and knowledge of the condition. As the field of sleep medicine is interdisciplinary, the training requirements for the diagnosis and treatment of people with sleep disorders should be the same across all medical specialties. At present, they vary enormously, which is why there are currently large gaps in medical knowledge and associated gaps in health care. Only with an additional specialist qualification in sleep medicine can a consistent approach be assumed. There is a need for inclusion of sleep medicine curricula in the training of some specialties and the general inclusion of comparable sleep medicine content, including insomnia, in teaching. As far as sleep medicine care is concerned, more interdisciplinary sleep outpatient clinics specializing in insomnia and the implementation of guideline-based specific treatment pathways for the individualized management of chronic insomnia are needed [3, 29].

Interestingly, more than 70% (394/532) of people with insomnia stated that they did not take any prescription medication despite their symptoms, and for the most part had never even been offered this by their physician. This may be due to the fact that the primarily recommended and available benzodiazepines and Z‑drugs are only authorized as short-term therapy. They should therefore generally only be prescribed for up to 4 weeks, including the tapering phase, and may also be a reason for medical reluctance in prescribing due to their potential for dependency or loss of efficacy. In addition, there is often skepticism on the part of both the prescribing specialists and the patients towards potentially addictive medications, which prevents them from being prescribed. As only prescribed medications were surveyed, it is not possible to make any statements about other treatment options, including behavioral therapy interventions or the use of over-the-counter medicines. It is known from the literature that currently only around 10% of sufferers receive conventional structured CBT‑I [23, 27]. Individual components of behavioral therapy such as sleep hygiene or relaxation techniques are used more frequently, but there are no scientific data on this. Digital health applications (DiGA) are now regularly available in the SHI system for the treatment of insomnia [16], which open up new possibilities in the structured support of people with sleep disorders, but no data are yet available on their effectiveness in everyday care.

The participants in the two analyzed cohorts were around 50 years old on average and the majority were female. This gender and age distribution is in line with other studies [27, 29]. The data show that people with insomnia in Germany appear to be socially disadvantaged. The proportion of SHI overage vs. private insurance in the insomnia cohorts was also significantly higher than among all German NHWS participants, although the distribution among all NHWS participants corresponded to that of the general population. Compared to the overall respondents (at least one comorbidity at 20.1%), the proportion with at least one comorbidity was twice as high in both insomnia cohorts (DT, 39.1%; DUt, 38.3%). The most frequently reported comorbidities of insomnia were pain (DT, 65.2%; DUt, 68.5%), followed by depression (DT, 55.8%; DUt, 49.2%). The high proportion of people in the insomnia cohorts with a reported anxiety disorder is striking. The data are also significant in terms of the comparison of insomnia cohorts vs. non-insomnia cohorts. Although it is not possible to say to what extent impairments in everyday life can also be attributed to the comorbidities, the data suggest that sleep disorders can be associated with various other health disorders and can have a bidirectional relationship [14].

Overall, at the time of the survey, only around 30% of adults with insomnia reported that they were receiving prescription medication (= DT cohort), mostly in the form of non-B/non‑Z or off-label medications. The reasons for the high proportion of non-B/non‑Z or off-label prescriptions cannot be determined from the self-reported data. Of those treated with medication, around 50% state that the severity of their sleep disorders and the effect on their daily wellbeing are significantly higher if they do not take medication. This could also be the reason why it is precisely these sufferers in the DT cohort who receive medication at all. However, the data suggest that the duration of treatment in the DT cohort is more than 40 months for B and Z‑drugs, which significantly exceeds the recommended prescription period. The literature describes that people with insomnia also resort to private prescriptions [4, 9, 19, 27]. Those affected also have their medication prescribed by several medical specialists in succession [27]. This could suggest a high level of suffering on the part of those affected and restricted prescribing on the part of the treating physicians, or it could be a sign of high consumption due to addiction and dependence. This finding is in line with the German government’s addiction report [9]. A recently published study confirms the prescribing behavior of physicians, as there was an increase in private prescriptions for benzodiazepines and Z‑drugs among those insured by statutory health insurance (SHI) in Germany between 2014 and 2020, with SHI prescriptions falling [19]. According to the current guideline on drug dependence published by the Drug Commission of the German Medical Association, benzodiazepines and Z‑drugs are the leading substances for drug dependence [4]. These findings support the statement regarding massive underuse and misuse, particularly in chronic insomnia, and reflect a high need for new innovative, inclusive pharmacological treatment options.

Symptoms of insomnia affect health as well as mental and physical performance and thus also impair labor productivity [18, 27]. This is also shown in the present analysis. Estimated EQ-5D standard values for the total population in Germany show that approximately 60% have a value of 0.92, which corresponds to the statement “no problem” for all items surveyed [25]. The health status of the overall German NHWS respondents was better than that of the people with insomnia: with a mean value of 0.88 for the EQ-5D-5L index value, the overall respondents were in the upper range. For both insomnia cohorts—with values of 0.73 (DT) and 0.76 (DUt)—there were relevant effects [25] of insomnia on the state of health. In contrast to the overall respondents, respondents in both cohorts stated on average two to three times more frequently that they were absent from work. The small differences in the cohorts could be due to the influence of insomnia on health status as measured by EQ-5D.

Overall, the care situation with regard to differential diagnosis and treatment appears to be inadequate and leads to long periods of illness. The question is how healthcare services can be adapted in future and how the availability of targeted treatment options can be improved.

Limitations

The following limitations result from the study design:

-

The analysis was based on non-verified self-reports, and a definitive diagnosis according to ICSD‑3 (in particular acute vs. subacute vs. chronic insomnia) [24] was not possible, nor was an analysis of the influence of comorbidities such as depression, anxiety disorder, and pain symptoms on the severity and course of insomnia. Data on the severity or type of insomnia (sleep onset, sleep maintenance, early morning awakening) were also not collected.

-

The survey only asked about prescribed medications, not about over-the-counter sleeping pills purchased directly from pharmacies without a prescription or about non-pharmacological treatment such as cognitive behavioral therapy or its components.

-

The two cohorts analyzed were of unequal size.

Conclusion for practice

Due to the considerable burden of insomnia and its effects on daytime functioning, improving the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia has both individual and societal consequences. The available data show for the first time the discrepancy between the unmet need and current care. This emphasizes the need to expand healthcare services and the availability of targeted treatment options. In order to be able to digitally map sleep medicine treatment and care, it is necessary to switch to ICD-11 as the basis for coding because the prevalence of insomnia cannot be mapped in the current coding systems. Only this change will allow insomnia to be recognized as an independent disorder in the German healthcare context and, by taking the phenotype into account, can form the basis for future treatment concepts and a targeted allocation of resources. This could enable an expansion of healthcare services and thus improve the availability of access to targeted treatment options.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM‑5, 5 edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, D.C.

Baglioni C, Spiegelhalder K, Lombardo C, Riemann D (2010) Sleep and emotions: a focus on insomnia. Sleep Med Rev 14(4):227–238

Benjamin SE, Exar EN, Gamaldo CE (2023) An Integrated Interdisciplinary sleep care model-the ultimate dream team. JAMA Neurol 80(6):541–542

Bschor T (2022) II. Substanzspezifische Fragen. Benzodiazepine und Benzodiazepinanaloga (Z-Substanzen). https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/fileadmin/user_upload/BAEK/Themen/Public_Health/Leitfaden-Medikamentenabhaengigkeit_final-Internetfassung.pdf. Zugegriffen: 6. Juli 2023 (Leitfaden „Schädlicher Gebrauch und Abhängigkeit von Medikamenten“ Herausgegeben von der Bundesärztekammer in Zusammenarbeit mit der Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft 7–12)

Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (2023) ICD Internationale statistische Klassifikation der Krankheiten und verwandter Gesundheitsprobleme. https://www.bfarm.de/DE/Kodiersysteme/Klassifikationen/ICD/_node.html. Zugegriffen: 4. Aug. 2023

Chalet FX, Bujaroska T, Germeni E et al (2023) Mapping the insomnia severity index instrument to EQ-5D health state utilities: a United Kingdom perspective. Pharmacoecon Open 7(1):149–161

Chouvarda I, Mendez MO, Rosso V et al (2012) Cyclic alternating patterns in normal sleep and insomnia: structure and content differences. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 20(5):642–652

Destatis (2021) Gesundheit. Tiefgegliederte Diagnosedaten der Krankenhauspatientinnen und -patienten. 2019. Artikelnummer 5231301197015. https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/receive/DEHeft_mods_00140902. Zugegriffen: 23. Juni 2023

Die Drogenbeauftragte der Bundesregierung (2015) Drogen- und Suchtbericht 2015. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/5_Publikationen/Drogen_und_Sucht/Broschueren/2015_Drogenbericht_web_010715.pdf. Zugegriffen: 23. Juni 2023

Dieck A, Morin CM, Backhaus J (2018) A german version of the insomnia severity index. Somnologie 22:27–35

Ellert U, Kurth BM (2013) Gesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 56:643–649

Espie CA, Pawlecki B, Waterfield D et al (2018) Insomnia symptoms and their association with workplace productivity: cross-sectional and pre-post intervention analyses from a large multinational manufacturing company. Sleep Health 4(3):307–312

Fietze I, Laharnar N, Koellner V, Penzel T (2021) The different faces of insomnia. Front Psychiatry 12:683943

Finan PH, Smith MT (2013) The comorbidity of insomnia, chronic pain, and depression: dopamine as a putative mechanism. Sleep Med Rev 17(3):173–183

Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss Beschluss des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses über eine Änderung der Arzneimittel-Richtlinie. https://www.g-ba.de/downloads/39-261-6008/2023-05-12_AM-RL-XII_Daridorexant_D-891_BAnz.pdf. Zugegriffen: 23. Juni 2023 (Anlage XII – Nutzenbewertung von Arzneimitteln mit neuen Wirkstoffen nach § 35a des Fünften Buches Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB V) Daridorexant (Schlafstörungen) (Banz AT 19.06.2023 B4))

GKV-Spitzenverband Bericht des GKV-Spitzenverbandes über die Inanspruchnahme und Entwicklung der Versorgung mit digitalen Gesundheitsanwendungen (DiGA-Bericht). https://www.gkv-spitzenverband.de/media/dokumente/krankenversicherung_1/telematik/digitales/2022_DiGA_Bericht_BMG.pdf. Zugegriffen: 2. Mai 2023 (Bericht des GKV-Spitzenverbandes über die Inanspruchnahme und Entwicklung der Versorgung mit digitalen Gesundheitsanwendungen (DiGA-Bericht) gemäß § 33a Absatz 6 SGB V; Berichtszeitraum: 01.09.2020–30.09.2022)

Godet-Cayré V, Pelletier-Fleury N, Le Vaillant M et al (2006) Insomnia and absenteeism at work. Who pays the cost? Sleep 29(2):179–184

Gottesmann C (2002) GABA mechanisms and sleep. Neuroscience 111(2):231–239

Grimmsmann T, Kostev K, Himmel W (2022) The role of private prescriptions in benzodiazepine and Z‑drug use—a secondary analysis of office-based prescription data. Dtsch Ärztebl Int 119:380–381

Harvey AG (2002) A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther 40(8):869–893

Hajak G, SINE Study Group. Study of Insomnia in Europe (2001) Epidemiology of severe insomnia and its consequences in Germany. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 251:49–56

Hoffmann F (2013) Benefits and risks of benzodiazepines and Z‑drugs: comparison of perceptions of GPs and community pharmacists in Germany. Ger Med Sci 11:1–7

Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Germany GmbH Modul 3. In: AMNOG Dossier Daridorexant Chronische Insomnische Störung (Behandlungsdauer 28 Tage). https://www.g-ba.de/bewertungsverfahren/nutzenbewertung/900/. Zugegriffen: 23. Juni 2023

American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2014) International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3 edn. American Academy of Sleep Medicine, Darien, IL

Leidl R, Reitmeir P (2017) An experience-based value set for the EQ-5D-5L in Germany. Value Health 20(8):1150–1156

Mann NK, Mathes T, Sönnichsen A et al (2023) Potentially Inadequate Medications in the Elderly: PRISCUS 2.0—First Update of the PRISCUS List. Dtsch Ärztebl Int (arztebl.m2022.0377)

Marschall J, Hildebrandt S, Sydow H, Nolting HD (2017) Gesundheitsreport 2017 (DAK Report). Medhochzwei Verlag, Heidelberg

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM (1993) The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. PharmacoEconomics 4(5):353–365

Riemann D, Baum E, Cohrs S et al (2017) S3-Leitlinie Nicht erholsamer Schlaf/Schlafstörungen (AWMFRegisternummer 063-003). Somnologie 21:2–44

Riemann D, Espie CA, Altena E, et al. (2023) The European Insomnia Guideline: An update on the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia 2023. J Sleep Res 32:e14035. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.14035

Stranks EK, Crowe SF (2014) The acute cognitive effects of zopiclone, zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 36:691–700

Watson NF, Benca RM, Krystal AD, McCall WV, Neubauer DN (2023) Alliance of sleep clinical practice guideline in switching or deprescribing hypnotic medications for insomnia. J Clin Med 12:2493

Acknowledgements

The authors thank D. Jaffe, J. Thompson, and K. Modi of the NHWS EU5 Survey Team Cerner Enviza and J. E. Matos of the NHWS EU5 Survey Team Kantar Health for the Germany-specific analyses on behalf of Isorsia Pharmaeuticals Ltd., Allschwil, Switzerland; P. Liauw, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Germany GmbH, for coordination and critical review; and C. Lorenz-Schlüter, Alcedis GmbH, Giessen, Germany, for assistance with medical writing, for which Alcedis received financial compensation from Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Germany GmbH, and K. Neou-North, Senior Publications Manager, Idorsia Pharmceuticals Ltd., Allschwil, Switzerland, for critical review of the English translation. Special thanks to R. Goertz, AMS Mannheim, Germany, for additional statistical support during the peer-review process, for which AMS Advanced Medical Services GmbH received financial compensation from Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Germany GmbH, Munich, Germany.

Funding

Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Allschwil, Switzerland; Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Germany GmbH, Munich, Germany.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

A. Heidbreder declares that she has received payments or honoraria for lectures, presentations, etc. from Jazz Pharmaceuticals Ltd. and UCB, travel support from Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and has participated in a data safety monitoring panel of Desitin and Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. outside the submitted work. D. Kunz declares that he has received research support and other benefits from Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. in Allschwil, BL, Switzerland, outside the submitted work. P. Young, an employee of the Medical Park Hospital Group, declares that he has received lecture fees from Bioprojet, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Medice, Löwenstein Medical, Somnomedic, Amiczus, and Sanofi outside the submitted work. He has also received consulting fees from Sanofi, Medice, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd., and Jazz Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. H. Benes, an employee of the Somni Bene Institute for Medical Research and Sleep Medicine Schwerin GmbH, Schwerin, Germany, is head of the Sleep Laboratory Schwerin, a specialized sleep laboratory for neuropsychiatric disorders, which has received financial research support for conducting clinical trials from Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. outside the submitted work. F.-X. Chalet and C. Vaillant are employees of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. P. Kaskel is an employee of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Germany GmbH. I. Fietze declares that he has received consultancy fees from Bayer, Bioprojet, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, STADA, and Takeda outside the submitted work. C. Schöbel declares that he has received institutional and other support from AstraZeneca, Novartis and ResMed, other support from Berlin Chemie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Löwenstein Medical and novamed as well as Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Sleepiz, Mementor DE, outside the submitted work.

No human or animal studies were conducted by the authors for this paper. The NHWS 2020 protocol and questionnaire were reviewed by the Pearl Institutional Review Board (Indianapolis, IN, USA; 19-KANT-204) and received “exemption status study sample” status [6].

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heidbreder, A., Kunz, D., Young, P. et al. Insomnia in Germany—massively inadequate care?. Somnologie (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-024-00460-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-024-00460-9