Abstract

Constructive interference between tidal stream turbines in multi-rotor fence configurations arrayed normally to the flow has been shown analytically, computationally, and experimentally to enhance turbine performance. The increased resistance to bypass flow due to the presence of neighbouring turbines allows a static pressure difference to develop in the channel and entrains a greater flow rate through the rotor swept area. Exploiting the potential improvement in turbine performance requires that turbines either be operated at higher tip speed ratios or that turbines are redesigned in order to increase thrust. Recent studies have demonstrated that multi-scale flow dynamics, in which a distinction is made between device-scale and fence-scale flow events, have an important role in the physics of flow past tidal turbine fences partially spanning larger channels. Although the reduction in flow rate through the fence as the turbine thrust level increases has been previously demonstrated, the within-fence variation in turbine performance, and the consequences for overall farm performance, is less well understood. The impact of turbine design and operating conditions, on the performance of a multi-rotor tidal fence is investigated using Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes embedded blade element actuator disk simulations. Fences consisting of four, six, and eight turbines are simulated, and it is demonstrated that the combination of device- and fence-scale flow effects gives rise to cross-fence thrust and power variation. These cross-fence variations are also a function of turbine thrust, and hence design conditions, although it is shown simple turbine control strategies can be adopted in order to reduce the cross-fence variations and improve overall fence performance. As the number of turbines in the fence, and hence fence length, increases, it is shown that the turbines may be designed or operated to achieve higher thrust levels than if the turbines were not deployed in a fence configuration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A key difference between wind turbines and tidal stream turbines is that tidal stream turbines generally lie in close proximity to the flow passage boundaries, such as the seabed, sea surface, as well as the presence of neighbouring turbines. The relative balance and interactions of the flow through the turbines, the core flow, and the flow around the turbines, the bypass flow, in a volume-constrained flow passage has an important effect on the overall energy available to the turbines.

Garrett and Cummins (2007) demonstrated analytically the importance of the blockage ratio, the ratio of turbine swept area to the cross-sectional area of the flow passage surrounding the turbine, BL, for predicting tidal stream turbine performance. Using an idealised representation of tidal turbines as actuator disks, it was shown that the theoretical peak power coefficient increases by a factor of (1-BL)−2 above the Lanchester-Betz limit, CP = 16/27. The principles of conservation of mass and momentum can be used to show that a static pressure (head) difference develops in the flow passage between positions far upstream and downstream of the actuator disk as a result of momentum removal from the flow. This increases the available static pressure difference across the rotor plane, as compared to a wind turbine (where the flow passage is not constrained), and hence the maximum power coefficient increases because higher thrust levels can be sustained by the flow.

The work of Garrett and Cummins on tidal turbine efficiency has been extended theoretically and numerically to configurations of multiple turbines in side-by-side and staggered configurations, as well as to consider the role of multi-scale hydrodynamics when a turbine fence does not span the entire channel cross-section (Nishino and Willden 2012; Nishino and Willden 2013; Draper and Nishino 2014; Vogel et al. 2016). The multi-scale hydrodynamics that arise when a tidal fence does not span the channel width has also been demonstrated experimentally for actuator disks by Cooke et al. (2015). It is useful to define the global blockage ratio, BG, as the ratio of the frontal area of all turbines in an array to the cross-sectional area of the tidal channel when describing the multi-scale flow phenomena that arise.

Exploiting the uplift in turbine performance that is theoretically available in volume-flux confined conditions requires that the tidal turbines are capable of supporting the higher levels of thrust required to access the improved levels of available power (Schluntz and Willden 2015). There are two broad methods to achieve the higher thrust levels required to realise the theoretically available increased power levels; operating the turbines at higher tip speed ratios, or redesigning the rotor to increase the solidity ratio in order to increase the blade forces. The maximum rotational speed of the turbine may be limited to avoid cavitation inception along the blade, restricting the operational tip speed ratio range (DNV GL 2015). Consequently, there is interest in designing tidal stream turbine blades to harness the increased available power when the turbines are deployed in moderate and high-blockage environments.

Experimental work on fences of actuator disks partially spanning a tidal channel by Cooke et al. (2015) demonstrated that cross-fence variations in thrust and power develop as a result of the changing incident flow conditions across the fence. This cross-fence variation, in which turbine power reduces towards the ends of the array, can be significantly detrimental to the overall farm power for short fences of tidal turbines. Cross-fence performance variations for short fences of turbines were also investigated by Nishino and Willden (2013) using computational models. However, there have been few studies investigating cross-fence variation in thrust and power and the consequent impact on the design of tidal stream turbines for deployment in fence configurations.

This paper addresses the question of turbine design within short cross-stream fences of tidal turbines. Although the potential performance improvement available from deploying turbines in a closely spaced configuration has been discussed in the work above, the process of designing turbines to best exploit the potential performance improvement has yet to be determined. Turbines designed for a range of local blockage ratios are investigated in multi-rotor configurations of four, six, and eight turbines, where the inter-turbine tip-to-tip spacing between turbines is held constant at one turbine diameter.

2 Computational Model

The commercial CFD solver ANSYS Fluent v.15.0 was used for the numerical simulations in this study. The simulations in Fluent were performed as steady computations solving the incompressible 3D Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations with a finite volume method. Turbulence closure was provided by the k-ω SST model (Menter 1994), which has been successfully used in both marine and wind turbine studies (Mahu and Popescu 2011). The k-ω SST model combines the advantages of the k-ω model near no-slip boundaries, such as the nacelle, with the k-ε model in the remainder of the domain.

The tidal turbines were modelled as actuator disks, defined using the ‘fan’ internal boundary condition in Fluent. A RANS-embedded Blade Element Actuator Disk (RANS-BE AD) model was implemented with user defined functions, following (McIntosh et al. 2011) to represent the turbines. The RANS-BE AD model sampled the numerically simulated flow field at the location of the actuator disk and, in conjunction with the rotor geometry and aerofoil data, the azimuthally-averaged axial and tangential forces acting on the rotor blades were calculated using blade element theory. The spanwise azimuthally varying forces were imposed on the flow across the fan internal boundary as a static pressure discontinuity and change in swirl velocity. Modelling differences between three-dimensional rotors and the actuator disks being simulated (approximated as rotors with infinitely many blades) were accounted for using the Prandtl tip loss model (Glauert 1935). The tip loss model, applied to the blade element calculations using the numerically simulated axial flow speed, attempts to account for the difference in flow speed incident on the rotor blades with the azimuthally averaged flow speed through the actuator disk.

The rotors simulated in this work were based on those proposed by Schluntz and Willden (2015) and extended by Vogel and Willden (2017a, b). The rotors had three blades and were d = 20 m in diameter. The nacelle had a hemispherical nose and tail, a diameter of 0.15d, and was 0.5d in length. For computational simplicity, the rest of the rotor support structure was not simulated. A single aerofoil section was used for the blades; the Risø A1-24 section, which has a maximum thickness of 24% and good lift-to-drag characteristics (Fuglsang and Bak 2004). The maximum lift-to-drag ratio of the Risø A1–24 aerofoil occurs at an angle of attack of α = 5°. The uniform flow velocity into the computational domain was u∞ = 2 m·s−1, with seawater (ρ = 1025 kg·m−3) used as the working fluid.

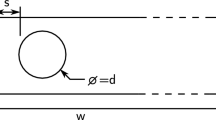

Multi-rotor simulations of four, six, and eight identical turbines were performed in a rectangular computational domain with height h = 2d (similar to sites under consideration and development, such as the Meygen site, where d = 20 m). The actuator disks were arrayed normal to the flow direction in the yz-plane, centred on x = y = z = 0, in a configuration as illustrated in Fig. 1. A constant inter-turbine tip-to-tip spacing ratio s/d = 1 was specified in all cases, so that the local blockage ratio within the fence was \( {B}_L=\frac{1}{4}\uppi {d}^2/h\left(s+d\right)=0.1960 \). The width of the domain was scaled so that the global blockage ratio, which describes the importance of array-scale flow phenomena, \( {B}_G=\frac{1}{4}n\uppi {d}^2/{w}_cd=0.0507, \) in each of the simulations, where n is the number of turbines. In the four turbine case, wc = 31d, and was wc = 46.5d and wc = 62d in the six and eight turbine simulations respectively. The computational domain extended 17d upstream and 55d downstream of the rotor fence.

The mesh was block-structured and consisted of hexahedral elements. Mesh resolution at the rotor plane was varied across the disk face in order to increase resolution near the disk edge, with the minimum element length specified as ϵmin = 1/135d, and the maximum disk plane element length set as ϵmax = 1/30d. The growth rate in the streamwise direction was 1.1 in the wake region. Following a mesh sensitivity study, the domain contained about 7 × 106 elements, with normalised residuals reducing below 10−5 after approximately 7000 iterations. The channel-free surface was modelled as a rigid lid, with slip wall boundary conditions to the top and bottom surfaces of the domain. Symmetric boundary conditions were applied to the lateral walls.

The turbines were assumed initially to operate at a constant and uniform tip speed ratio across the fence and that they contra-rotate.

3 Rotor Selection

Five rotor designs were investigated in this work. The rotors were designed for five blockage ratios by Vogel and Willden (2017a). The lowest blockage ratio, BL = 0.0001, matches that for turbine designed without considering blockage effects (i.e., a wind turbine). The BL = 0.1960, design was selected to match the local blockage ratio determined by the inter-turbine spacing in multi-rotor fence. A rotor was designed to correspond to the global blockage ratio of the multi-rotor configuration, BL = 0.0507. Two intermediate blockage designs were also investigated, one at a lower design blockage ratio, BL = 0.0357, than the global blockage ratio, and one at a higher design blockage ratio, BL = 0.0650. The blockage ratios were selected to correspond to doubling and halving the tip-to-tip spacing of the global blockage turbine design.

All rotors were designed to target a prescribed angle of attack in order to maximise the 2D aerofoil lift-to-drag ratio, 5̊ for the Risø A1-24 aerofoil. The rotor design process also aims to maintain a constant local thrust coefficient along the blade span. The local thrust coefficient is defined as \( {C}_x=\Delta {F}_x/\frac{1}{2}\rho {u}_x^2 \), where ΔFx is the applied axial force per unit area, ρ is the fluid density, and ux is the axial flow speed. As shown in Fig. 2, inboard of a relative radial position r/R = 0.26, the blade is tapered to a cylindrical section at the root, resulting in a reduction in blade twist angle and solidity ratio, following Wimshurst and Willden (2016).

Blade solidity, σ, (a) and blade twist angle, β, (b) for the five rotor designs from Vogel and Willden (2017a) studied in this work. The local design blockage ratios were BL = 0.0001 (black), BL = 0.0357 (red), BL = 0.0507 (orange), BL = 0.0650 (green), and BL = 0.1960 (blue). The solidity ratio increases with design blockage ratio, whereas the blade twist angle reduces

The maximum power and thrust coefficients of the turbines increase with design blockage ratio, as increasing the blockage ratio results in an increased constraint of the flow passage bypassing the turbine, and hence greater acceleration of the bypass flow in order to maintain continuity. Static pressure is consequently reduced in the bypass flow, and thus there is also a reduced static pressure in the core flow when hydrostatic pressure equalisation occurs between the bypass and core flows. The increased static pressure across the turbine means that, for a given mass flow rate, higher blockage ratio turbine configurations can apply a greater thrust to the flow than lower blockage turbines. The maximum turbine power coefficient is hence increased, as the flow can sustain a higher level of resistance in higher blockage conditions before becoming choked. This is reflected in the turbine designs shown in Fig. 2, where the rotor solidity σ = NBc(r)/2πr, where NB is the number of blades, and c(r) is the blade chord at radius r, increases with blockage ratio in order to support higher turbine thrust at a given design tip speed ratio (the design tip speed ratio was λ = 5.00). The increased turbine thrust allows a larger torque to be developed by the rotor, and hence power is increased. There is a much smaller variation in blade twist angle, which reduces with increasing design blockage ratio. There is a blade twist angle variation of up to 1° between the lowest (BL = 0.0001) and highest (BL = 0.1960) blockage designs.

Following Vogel and Willden (2017a), the maximum power coefficients and the corresponding thrust coefficient and tip speed ratio at which they are achieved, for the five different designs in their design blockage ratios are given in Table 1. It should be noted that the peak power coefficient may be achieved at a different tip speed ratio than the design λ = 5, as increasing the rotational speed of the rotor results in increased thrust and hence a greater static pressure difference. This can result in an increased rotor torque, and therefore power. However, it should be noted that redesigning the rotor for the new, higher, tip speed ratio would result in a design that would achieve an even higher power coefficient in those conditions. Vogel and Willden found that a higher power coefficient was achieved by the higher blockage ratio turbine designs, although there was also an increase in turbine thrust coefficient and tip speed ratio at which this was achieved. Deploying turbines in higher blockage conditions than their design blockage was found to increase the peak power coefficient. This was achieved at higher tip speed ratios than given in Table 1 in order that the turbines were able to apply a sufficiently high level of resistance to the flow to exploit the increased static pressure difference that could be supported in the channel.

4 Multi-Rotor Fence Performance

Multi-rotor fences, consisting of four, six, or eight turbines arrayed in the cross-stream direction as shown in Fig. 1, with an inter-turbine tip-to-tip spacing of s/d = 1 (BL = 0.1960) and a global blockage ratio BG = 0.0507, were simulated across a range of operating conditions. The turbines were numbered, starting at 0, from left to right across the fence. The left- and right-most turbines in the fence were denoted the ‘outboard’ turbines, whereas the other turbines were referred to as ‘inboard’ turbines. The turbines counter-rotate, so that even numbered turbines rotate anti-clockwise, and odd numbered turbines rotate clockwise.

4.1 Effect of Fence Length on Mean Performance

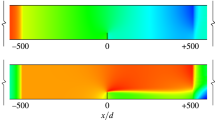

The effect of tip speed ratio on the mean fence power and thrust coefficient for the three different fence lengths is shown in Fig. 3, where the tip speed ratio is constant across the fence. The fence thrust coefficient increases as the tip speed ratio increases, due to the increased blade forces that are generated. Fence thrust increases with design blockage ratio, as the increased solidity of the higher blockage designs results in increased blade forces. The fence thrust coefficient also increases with fence length. The inboard turbines, with neighbouring turbines on both sides, are able to achieve higher levels of thrust than the outboard turbines due to the resistance to bypass flow acceleration presented by neighbouring turbines on both sides. Bypass flow resistance is reduced for the outboard turbines due to the presence of the array bypass flow, which results in reduced flow through the turbines and hence lower thrust levels. As the fence length and hence the ratio of inboard to outboard turbines increases, the fence thrust coefficient increases due to the greater number of high thrust turbines within the fence. This effect becomes more important as the tip speed ratio increases, because the bypass flow interactions between turbines become more significant as turbine thrust increases.

Mean fence power coefficient, (a) and thrust coefficient, (b) for the five rotor designs in cross-stream fences of four (dot-dashed), six (dashed), and eight (solid) turbines. The local design blockage ratios were BL = 0.0001 (black), BL = 0.0357 (red), BL = 0.0507 (orange), BL = 0.0650 (green), and BL = 0.1960 (blue)

The mean fence power coefficient is also a function of rotor design, tip speed ratio, and fence length. The fence power coefficient is higher at low tip speed ratios as the design blockage ratio increases because the large blade forces generate increased torque. However, as the tip speed ratio, and, therefore, the resistance, the fence presents to the flow increases, the high blockage designs cause more array-scale flow diversion around the fence, limiting the maximum power that is achieved. Consequently, the lower blockage turbine designs achieve higher fence power coefficients than the high blockage turbine designs at high tip speed ratios. In all cases, the lowest blockage design (BL = 0.0001) design achieves the highest fence power coefficient at λ = 7.00, albeit a lower CP than the peak value achieved by any of the designs. The fence power coefficient increases with fence length, as there are a greater number of turbines operating at the high levels of thrust required to maximise turbine performance. Fence length has the largest effect on the highest blockage design (BL = 0.1960) because it is also the design that is most reliant on turbine-turbine interefence effects to achieve its potential, single turbine design, performance.

Table 2 shows the maximum farm power coefficient achieved by the five different blockage designs as fence length increases. Through comparison with Table 1, it can be seen that deploying the turbines in a fence configuration, even of just four turbines, results in improved fence power coefficients as compared to the design conditions for all turbine designs below the local blockage ratio. This is because the constructive turbine-turbine interefence effects that occur within the fence allow the turbines to sustain a higher thrust than is possible in their design conditions. This is achieved by operating the devices at a higher tip speed ratio than they were designed for, and cavitation inception constraints on the permissible rotational speed may impose a limit on device performance. It should be noted that the inboard turbines operate at a slightly higher power coefficient than the outboard turbines.

Table 2 also shows that, in sufficiently long fences, it is possible for the fence power coefficient to exceed the Betz limit, CP = 0.5923. This is because the turbines remove energy from the static head in the volume-flux constrained channel flow. The static head difference upstream and downstream of the fence increases as the fence resistance increases, which occurs both by deploying higher thrust turbines (higher design blockage turbines), and also by increasing fence length, even at a constant global blockage ratio.

The design blockage ratio that maximises the fence power coefficient, and corresponding fence performance values, are shown in Table 3. For a fence of four turbines, the high blockage (BL = 0.1960) design, although designed for the local blockage ratio, achieves a significantly lower maximum power coefficient than the lower blockage designs. The BL = 0.0650 design turbines achieve the best performance, with a peak CP = 0.5705. The required tip speed ratio is λ = 5.50 is slightly higher than the design tip speed ratio (λ = 5.00) in order to achieve the increased level of resistance required to harness the static pressure difference that develops in the channel. It should be noted that the peak performance of all the other designs, except for the BL = 0.1960 design, achieve a very similar peak power coefficient, albeit it at higher tip speed ratios.

The BL = 0.0650 design turbines also achieve the highest fence power coefficient in the six turbine fence, slightly exceeding the Betz limit at CP = 0.5943. A higher tip speed ratio, λ = 6.00, is required to achieve the even higher levels of resistance that can be supported in the channel. Increasing the fence length to eight turbines, the BL = 0.1960 turbines achieve the highest fence power coefficient, CP = 0.6138 at λ = 5.50, although this is only 1.35% greater than the peak power coefficient achieved by the lowest blockage design. The tip speed ratio of the lower designs is necessarily higher in order to achieve the required level of thrust.

The basin efficiency, the ratio of power to thrust coefficient, η = CP/CT, has been defined as a measure of the hydrodynamic power available to the turbines to the total power removed from the flow, including downstream mixing losses (Belloni and Willden 2011). Figure 4 shows that basin efficiency increases with fence length, with the greatest improvements observed in the transition from four to six turbines. As fence length increases, the volume flux, and hence core flow speed, through the inboard turbines (at constant λ and BL) also increases due to the reduced flow diversion around the inboard turbines caused by the presence of neighbouring devices. Consequently, there is reduced shear between the array core and bypass flows and hence reduced mixing losses in the wake. Basin efficiency increases as the turbine design blockage ratio decreases for a similar reason, as the higher flow rate through the fence achieved with lower blockage devices (at constant λ and fence length) also results in reduced mixing losses in the array wake.

Fence basin efficiency η variation with tip speed ratio for the five rotor designs in cross-stream fences of four (dot-dashed), six (dashed), and eight (solid) turbines. The local design blockage ratios were BL = 0.0001 (black), BL = 0.0357 (red), BL = 0.0507 (orange), BL = 0.0650 (green), and BL = 0.1960 (blue)

The turbine design and tip speed ratio that maximise fence basin efficiency for a given fence length are different from the design and tip speed ratio that maximise fence power. Whereas the maximum fence power coefficient is correlated with increasing the design blockage ratio, the substantial increase in farm thrust required to achieve this results in a reduction in fence basin efficiency. Consequently, the BL = 0.0001 design turbines are found to maximise basin efficiency for all fence lengths considered in this work, although the differences between the lowest and intermediate design blockage turbines are relatively small near the peak basin efficiency. In the case of an eight turbine fence, reducing the tip speed ratio of the BL = 0.1960 turbines from that which maximises the power coefficient to that which maximises the basin efficiency, an increase in basin efficiency of 10%, results in an 8.5% reduction in power coefficient. It should be noted that the farm power coefficient reduces more significantly at lower tip speed ratios for lower blockage turbines, and there is consequently a compromise required between increasing fence basin efficiency (and hence more efficient utilisation of the available tidal resource) and the attendant reduction in the fence power coefficient.

4.2 Cross-Fence Performance Variation

Figure 5 shows the cross-fence variation in power and thrust coefficient with fence length when the fence power coefficient is maximised for each turbine design. The rotors are numbered increasing from the fence centre, and only half the fence is shown (with results symmetric about the fence centre). Cross-fence variation in both the thrust and power coefficients increases with fence length, as a result of the increasing difference in bypass flow acceleration resistance between inboard and outboard turbines. Cross-fence variation also increases with increasing design blockage ratio, as the higher blockage turbines present a higher level of thrust to the flow and therefore generate higher speed bypass flows. This effect is most significant for the outboard-most BL = 0.1960 design turbine, as this design operates at substantially higher thrust levels than the other designs, as shown in Fig. 5b. In the eight turbine fence case, there is a 5.4% CP variation between the most inboard and outboard turbines for the BL = 0.1960, whereas the variation is only 3.8% in the case of the BL = 0.0001 design turbines. Consequently, although in the eight turbine fence, the inboard turbines for the highest blockage design turbines achieve higher CP than lower blockage turbines in the equivalent fence positions; the reduced CP of the outboard turbine means that the fence power coefficient is only slightly greater than the fence with BL = 0.0650 design turbines. Figure 5a shows that the detrimental effect the outboard turbine has on the overall fence power reduces as the number of turbines in the fence increases, and hence increasing fence length is most beneficial to high blockage turbine designs. Note that although cross-fence variation in thrust coefficient increases as the turbine design blockage ratio increases, for example from 1.8% between turbines 1 and 4 in the BL = 0.0001 case to 2.5% in the BL = 0.1960 case; overall fence basin efficiency increases with fence length as there is a greater variation in turbine power coefficient, as observed in Fig. 4.

Cross-fence variation in power coefficient (a) and thrust coefficient, (b) for the five rotor designs when mean fence power is maximised for cross-stream fences of four (dot-dashed), six (dashed), and eight (solid) turbines. The local design blockage ratios were BL = 0.0001 (black), BL = 0.0357 (red), BL = 0.0507 (orange), BL = 0.0650 (green), and BL = 0.1960 (blue)

Flow conditions are modified from the single turbine design conditions when tidal turbines are operated in a fence configuration. Figure 6 shows the potential for performance improvement, with both increased power coefficient and reduced thrust coefficient (and therefore improved basin efficiency) for a four turbine fence of BL = 0.1960 turbines at λ = 5.00. Adjusting the blade pitch angle to target the angle of attack that maximises the lift-to-drag ratio in the high torque portion of the blade span results in reduced drag and increased lift forces, increasing rotor torque and reducing thrust. The blade pitch of the inboard turbines was adjusted by 0.28° and 0.20° for the outboard turbines. The inboard turbines require a greater blade pitch angle adjustment as the axial flow speed through the turbines, and therefore the relative flow speed incident on the blades is lower than that for the outboard turbines. The available performance improvement is greater for higher blockage turbines as the turbines operate in conditions further from their design point than lower blockage turbines. The potential for performance improvement increases as the number of turbines in the fence increases due to the additional available degrees of freedom to increase the mass flow rate through the fence.

Cross-fence effect of differential blade pitching on a turbine power coefficient, and b thrust coefficient for a four turbine fence of BL = 0.1960 design turbines. The change in blade pitch angle for the inboard turbines (2 and 3) is βp = 0.28°, and βp = 0.20° for the outboard turbines. The tip speed ratio is λ = 5.00

5 Conclusions

The blockage ratio is an important parameter in determining the theoretical limit for the power available to a tidal stream turbine in a volume-flux constrained channel. Garrett and Cummins (2007) demonstrated that the maximum power coefficient can increase by a factor of (1-BL)−2 above the Betz limit if a sufficient level of resistance is applied to the flow by a uniform fence of tidal turbines. It was shown that momentum extraction in a volume-flux constrained flow results in the development of a static pressure difference which results in increased power available to the turbines. Subsequent work by Nishino and Willden (2012) and Vogel et al. (2016) demonstrated that a similar analysis can be conducted for a fence of turbines partially spanning a wide channel, with improved performance available if the turbines apply a sufficient level of resistance to the flow.

Schluntz and Willden (2015) used actuator line and blade element actuator disk simulations to investigate the effect of rotor design on turbine power, and showed that turbine performance is improved in high blockage configurations if the turbines are designed or operated (through increased rotational speed) to harness the increased static pressure difference. This has been extended to multi-rotor fence configurations, where it has been demonstrated by Vogel and Willden (2017a, b) and herein that the constructive interference effects that give rise to improved turbine performance are a function of turbine thrust. For all fence lengths, deploying relatively low blockage turbine designs (BL = 0.0001–0.0650) in the multi-rotor fence configuration, with BL = 0.1960, resulted in an increase in turbine power as compared to design conditions due to the constructive turbine-turbine interaction effects. The increase in power coefficient was greatest for the BL = 0.0001 design, increasing from CP = 0.484 to CP = 0.6082 in the eight turbine fence. A smaller increase was observed for the BL = 0.0650 design, from CP = 0.565 in a single turbine configuration to CP = 0.613 in the eight turbine fence. However, the peak power of the BL = 0.1960 turbine was reduced from CP = 0.739 to CP = 0.5164 in the four turbine fence, and CP = 0.6138 in the eight turbine fence, due to the presence of the array bypass flows. The rotational speed at which peak power was achieved for the low blockage ratio turbines in the multi-rotor configurations was higher than that under their respective design conditions as the lower blade solidity of those designs meant that a higher rotational speed was required in order to provide a sufficient level of resistance to the flow in order to maximise turbine performance. In practice, this is likely to be constrained by rotational speed limitations in order to avoid cavitation inception.

The best fence power coefficient was achieved by the BL = 0.0650 turbine design for fences consisting of four and six turbines (CP = 0.5705 and CP = 0.5943 respectively), although the BL = 0.1960 design achieved the best performance in an eight turbine fence, with CP = 0.6138. The tip speed ratio increased slightly from λ = 5.50 to λ = 6.00 to achieve the maximum fence power coefficient in the four and six turbine fence as a higher thrust could be sustained by the flow, increasing from CT = 0.9910 to CT = 1.0663. The BL = 0.0650 design had a sufficiently large blade chord to apply a sufficient level of thrust to the flow without choking the volume flux through the fence, as occurred with the BL = 0.1960 design. However, the BL = 0.1960 design achieved the highest overall power coefficient for an eight turbine fence, as the resistance to the bypass flow was sufficiently large for the inboard turbines to operate at a high enough CP level to compensate for the reduction in turbine performance towards the end of the fence.

Turbine basin efficiency, a measure of how efficiently the turbines exploit the available tidal resource, is generally improved in lower thrust conditions, such as by operating the turbines at lower tip speed ratios than that required to maximise the fence power coefficient, and also by using lower blockage turbine designs. The basin efficiency also increases with fence length as the mass flux through the fence is increased when the rotational speed of the turbines is constant, reducing the shear between the array core and bypass flows and therefore reducing downstream mixing losses. Cross-fence performance variation and basin efficiency, can be improved by adjusting turbine operating conditions within the multi-rotor fence configuration to target the turbine design conditions and thereby maximise the lift-to-drag ratio along the majority of the blade span. It was shown that this results in both a reduction in turbine thrust and increase in turbine power coefficients, and therefore also results in an increased basin efficiency, implying more efficient utilisation of the tidal resource.

These results have important practical implications for the design and operation of tidal turbine fences. Designing turbines to harness the theoretically available improvement in performance when deployed in closely spaced fence configurations comes from increasing the turbine thrust coefficient. This can be achieved either by increasing the rotational speed or the blade solidity of the turbines. However, a compromise is required between increasing the turbine power coefficient with an ensuing increase in turbine thrust, and the overall impact that the turbine has on the tidal resource, as represented by the basin efficiency. Furthermore, it has been shown that an approximately 5% increase in power coefficient could be available if differential pitching is used to modify turbine performance within the fence in order to slightly reduce turbine thrust and thereby increase the mass flow rate through the fence. Selecting the hydrodynamically optimal turbine design for operation in a multi-rotor fence configuration is thus a complex problem. Fence performance considerations include selecting the fence length and turbine design blockage ratio, determining the operational rotational speed when the turbines are deployed in a fence configuration to compromise between achieving a high power coefficient and high basin efficiency, as well as cross-fence performance control, such as by adjusting the blade pitch angle. Further to these considerations, and not considered here but discussed in Vogel and Willden (2017b), is the evaluation of fence performance above rated power.

References

Belloni C, Willden RHJ (2011) Flow field and performance analysis of bidirectional and open-centre ducted tidal turbines. In: Proc 9th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Southampton, United Kingdom

Cooke SC, Willden RHJ, Byrne B, Stallard T, Olczak A (2015) Experimental investigation of tidal turbine partial array theory using porous disks. In: Proc. 11th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Nantes, France

DNV GL (2015) Tidal turbines–rules and standards. Tech Rep. DNV GL-ST-0164

Draper S, Nishino T (2014) Centred and staggered arrangements of tidal turbines. J Fluid Mech 739:72–93. https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2013.593

Fuglsang P, Bak C (2004) Development of the Risø wind turbine airfoils. Wind Energy 7(2):145–162. https://doi.org/10.1002/we.117

Garrett C, Cummins P (2007) The efficiency of a turbine in a tidal channel. J Fluid Mech 588:243–251. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112007007781

Glauert H (1935) Airplane propellers. Springer Verlag, Berlin pp 167–269

Mahu R, Popescu F (2011) NREL Phase VI rotor modelling and simulation using ANSYS Fluent 12.1. Math Model Civil Eng 1/2:185–194

McIntosh SC, Fleming CF, Willden, RHJ (2011) Embedded RANS-BEM tidal turbine design. In: Proc. 9th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Southampton, United Kingdom

Menter FR (1994) Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J 32(8):1598–1605. https://doi.org/10.2514/3.12149

Nishino T, Willden RHJ (2012) The efficiency of an array of tidal turbines partially blocking a wide channel. J Fluid Mech 708:596–606. https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2012.349

Nishino T, Willden RHJ (2013) Two-scale dynamics of flow past a partial cross-stream array of tidal turbines. J Fluid Mech 730:220–244. https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2013.340

Schluntz J, Willden RHJ (2015) The effect of blockage on tidal turbine rotor design and performance. Renew Energy 81:432–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2015.02.050

Vogel CR, Willden RHJ (2017a) Designing multi-rotor tidal turbine fences. In: Proc 12th European Wave and Tidal Energy Conference, Cork, Ireland

Vogel CR, Willden RHJ (2017b) Multi-rotor tidal stream turbine fence performance and operation. Int J Marine Energy 19:198–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijome.2017.08.005

Vogel CR, Willden RHJ, Houlsby GT (2016) Effect of free surface deformation on the extractable power of a finite width turbine array. Renew Energy 88:317–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2015.11.050

Wimshurst A, Willden RHJ (2016) Computational analysis of blockage design tidal turbine rotors. In: Proc. Second International Conference on Renewable Energies Offshore, Lisbon, Portugal

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Article Highlights

• Designing tidal turbines for closely spaced operation can improve overall fence performance.

• Cross-fence variations in blade loads and power arise in short fence configurations.

• The magnitude of the cross-fence variations depends on fence length and turbine operation.

• Differential blade pitch control can be used to mitigate the effect of the variations and further improve array performance.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Vogel, C.R., Willden, R.H.J. Improving Tidal Turbine Performance Through Multi-Rotor Fence Configurations. J. Marine. Sci. Appl. 18, 17–25 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-019-00072-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-019-00072-y