Abstract

Purpose

To systematically review existing literature on knowledge and confidence of primary care physicians (PCPs) in cancer survivorship care.

Methods

PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO were searched from inception to July 2022 for quantitative and qualitative studies. Two reviewers independently assessed studies for eligibility and quality. Outcomes were characterized by domains of quality cancer survivorship care.

Results

Thirty-three papers were included, representing 28 unique studies; 22 cross-sectional surveys, 8 qualitative, and 3 mixed-methods studies. Most studies were conducted in North America (n = 23) and Europe (n = 8). For surveys, sample sizes ranged between 29 and 1124 PCPs. Knowledge and confidence in management of physical (n = 19) and psychosocial effects (n = 12), and surveillance for recurrences (n = 14) were described most often. Generally, a greater proportion of PCPs reported confidence in managing psychosocial effects (24–47% of PCPs, n= 5 studies) than physical effects (10–37%, n = 8). PCPs generally thought they had the necessary knowledge to detect recurrences (62–78%, n = 5), but reported limited confidence to do so (6–40%, n = 5). There was a commonly perceived need for education on long-term and late physical effects (n = 6), and cancer surveillance guidelines (n = 9).

Conclusions

PCPs’ knowledge and confidence in cancer survivorship care varies across care domains. Suboptimal outcomes were identified in managing physical effects and recurrences after cancer.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

These results provide insights into the potential role of PCPs in cancer survivorship care, medical education, and development of targeted interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer survivorship care is defined as the care of a person with cancer from the time of diagnosis until the end of their life [1]. Quality cancer survivorship care includes prevention and surveillance for recurrences and new cancers; surveillance and management of physical and psychosocial effects; surveillance and management of chronic medical conditions; and health promotion and disease prevention, as well as care coordination and communication [2]. Cancer survivors face a variety of challenges across all of these domains. Unfortunately, their needs are often unmet, regardless of whether they receive care in oncology or primary care settings [3, 4], leading to the investigation of optimal models of care. To date, oncology-led survivorship care remains common, but its sustainability and effectiveness to comprehensively treat cancer survivors has been questioned [5]. One of the alternatives to oncology-led care is care led by the primary care physician (PCP). Traditional core values of primary care — including its comprehensive, patient-oriented, and continuous care — may render PCP-led care more fitting compared to oncologist-led care, though a recent overview of systematic reviews has not found consistent differences in the models [6].

While PCPs appear willing to provide care for cancer survivors [7], persistent barriers continue to hinder the provision of care, specifically a lack of perceived knowledge and expertise of PCPs regarding the necessary care [8]. Prior reviews have described the attitudes and perceptions of PCPs’ on cancer survivorship care provision, but did not specifically address the knowledge and confidence according to its domains [7, 9,10,11]. Thus, the purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate PCPs’ knowledge and confidence in general and categorized by the domains of cancer survivorship care. In turn, this will help to inform the role of the PCP in the provision of cancer survivorship care and development of future interventions.

Methods

Design

This systematic review was prepared, adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines [12]. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022333944) prior to review commencement.

Main outcomes of interest

PCPs’ self-reported knowledge and confidence in providing cancer survivorship care were the main outcomes of interest. For the purpose of this review, knowledge was defined as the awareness, understanding, and skills obtained by experience or training, whereas confidence was defined as the feeling or belief to trust in oneself and one’s abilities, including self-efficacy, preparedness, and comfort in providing care. Studies that reported knowledge barriers and educational needs of PCPs were also included. We excluded studies if they only reported PCPs’ attitudes, beliefs, expectations, and preferences regarding the provision of cancer survivorship care.

Search strategy

A medical librarian (FJ) performed the initial search for studies in PubMed using MeSH terms related to survivorship care, primary care physicians, and the main outcomes. The MeSH terms were translated into corresponding terms to search the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO. Databases were searched for studies dating from inception to 01 July 2022.

Eligibility criteria

The population of interest was physicians providing primary or community-based survivorship care for cancer patients. The name for these physicians differs around the world and can include (but is not limited to): primary care physicians (PCPs), general practitioners (GPs) (sometimes referred to as GP specialists), and family physicians (FPs). Throughout this paper, “PCPs” will refer to all of these types of physicians. As the role of clinicians and nurses vary internationally, we focused this analysis on physicians only. While we included studies that surveyed different types of PCPs, we excluded those that did not report findings for PCPs alone. Any study design, including both quantitative and quantitative, were included. Letters to the editor and conference abstracts/papers that did not have a full manuscript available were not eligible. There were no restrictions based on type of cancer, publication date, or language. Studies were eligible if they described cancer survivorship care as the main topic or outcome of interest and reported on the main outcomes, described above.

Screening and data abstraction

Title and abstract screening was performed by two authors (JV and BW) using Covidence software [13]. Subsequently, all authors performed full-text screening. Full-texts were assessed independently by two authors. All authors performed data abstraction. Each paper had one author assigned to extract data and one author to check for accuracy. The following data were extracted: characteristics of the included study (author, year, country, aim, and methods), description of PCPs (including age, sex, previous training/certification, work setting, and number of years in practice), cancer survivor population of interest (general, adolescents/young adults, childhood, and specific cancer type), and main outcomes. Quantitative data abstraction included relevant numerical data, while qualitative data abstraction included synthesized findings. Screening and data abstraction discrepancies were managed by the two authors until consensus was reached through discussion. A third author was included in the discussion if necessary.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal assessments were performed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal tools for “Analytical Cross Sectional Studies” [14] and “Qualitative Research” [15]. Questions 3 and 4 from the “Analytical Cross Sectional Studies” checklist were not applicable to the main outcome and therefore not used. Similar to full-text screening, two authors independently conducted quality appraisal assessments of the eligible studies.

Data synthesis

Characteristics from all studies were compiled and presented in tabular format. Quantitative outcomes were analyzed using the framework method and mapped to the different domains of cancer survivorship care as proposed by Nekhlyudov et al. [2] specifically focusing on (1) prevention and surveillance for recurrences and new cancers; surveillance and management of (2) physical effects and (3) psychosocial effects; (4) surveillance and management of chronic medical conditions, and (5) health promotion and disease prevention. The framework has been previously applied to systematic reviews assessing cancer survivorship care and educational programs [6, 16,17,18]. Qualitative and other related outcomes were reported narratively.

Results

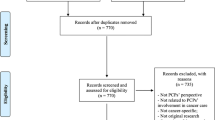

Initial database searches resulted in 2896 potentially eligible records. After title, abstract, and full-text screening, 33 papers were included, representing 28 unique studies (Fig. 1). The papers by Bober et al. and Park et al. were based on the same dataset [19, 20]. Similarly, 5 other studies were based on the same dataset [21,22,23,24,25], but were assessed as individual studies as they generally reported different outcomes.

Characteristics of the included studies

We included 22 quantitative studies (all cross-sectional survey design) [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40], 8 qualitative studies (7 interviews [41,42,43,44,45,46,47] and 1 focus group [48]), and 3 mixed-methods studies [49,50,51] (Table 1). The quantitative data reported by Heins et al. was not within the scope of this review, so only the qualitative data for this study was extracted [50]. The papers originated from 8 countries, most of which in North America (n = 23) and Europe (n = 8). The cancer survivor population of interest was not specified (n = 11) or focused specifically on survivors of breast cancer (n = 4), prostate (n = 4) or other type of cancer (n = 4). Some papers focused on multiple types of cancer (n = 5), childhood cancer (n = 3), or cancer in adolescents/young adults (n = 2). For the survey studies, sample sizes ranged from 29 to 1124 PCPs, with varying degrees of participation (from 14.9 to 65.1%). Overall, the surveyed population was predominantly male, White, around 50 years of age, and working in suburban or urban areas. All quantitative studies used Likert scale questions to gauge knowledge and confidence of PCPs. Likert scales ranged from 3 to 7 points, and outcomes were reported in different formats (%, means and percentiles).

Quality of the evidence

For the quantitative studies, risk of bias was often related to the identification of possible confounding factors and strategies to deal with them (n = 12) [19,20,21,22,23, 28,29,30, 35, 37, 40, 51] (Fig. 2). Some studies did not provide the time period of the survey (n = 5) [19, 24, 31, 49, 51] or provided little information about the population and sample sizes (n = 2) [28, 49]. In three studies, there was limited information about the surveyed population in general [28, 30, 32]. For the qualitative studies, none provided a clear statement locating the researchers’ cultural or theoretical background. Suboptimal quality was also related to a lack of underlying theoretical premises (n = 8) [41, 43,44,45, 47, 48, 50, 51], and addressing the influence of the researcher on the research (n = 7) [41, 43,44,45, 48, 50, 51]. Ratings of each individual study are provided in Supplementary file 1.

Quantitative outcomes

All outcomes were mapped to the different survivorship care domains and can be found in Supplementary file 2. Most papers described knowledge and confidence in the management of physical (n = 19) and psychosocial effects (n = 12), and of prevention and surveillance for recurrences and new cancers (n = 14) (Fig. 3). Outcomes of some studies (n = 5) could be mapped to multiple domains [19, 20, 25, 30, 33].

Prevention and surveillance for recurrences and new cancers

Ten studies described the PCPs knowledge, mainly described as skills, to conduct routine follow-up and management of recurrences and new cancers [21,22,23, 29, 33,34,35,36, 39, 49]. Five studies assessed the skills to provide “routine follow-up cancer care” (n = 5) [21, 22, 29, 35, 49]. In four of these studies, 41–59% of PCPs agreed that they had the necessary skills to provide follow-up [21, 22, 35, 49]. In a Norwegian study of patients with gynecological cancer, up to 78% of PCPs agreed or partly agreed they had the necessary skills to provide follow-up cancer care [29]. In other studies, between 62 and 78% of PCPs “somewhat or strongly agreed” they had the necessary skills to initiate appropriate screening and detection of recurrences (n = 5) [21,22,23, 34, 49]. In a single study from the Netherlands, only 20% agreed they “had the skills necessary to examine irradiated breasts to detect local recurrences and second tumors” [35]. Three studies also described the awareness and familiarity of surveillance guidelines [33, 36, 39]. In two of these studies, only 9–12% of PCPs felt at least “somewhat familiar” (Likert score ≥5) with guidelines [33, 39]. Lack of knowledge of evidence-based guidelines was mentioned as a barrier to providing care in two different studies [28, 31].

Confidence to screen for cancer recurrence was rated much lower across all the included studies. Between 6-42% felt very confident or prepared to do so (n = 6) [21, 29, 31, 32, 34, 49].

Surveillance and management of physical effects

Knowledge and confidence in management of physical effects was described in 13 studies. About half of these studies (n = 7) did not specify the physical effect under evaluation [21, 22, 24, 32, 39, 49, 51], while others (n = 6) focused on specific symptoms, such as fatigue and treatment-related osteoporosis [26, 28, 36,37,38, 40]. Only four studies examined knowledge of PCPs regarding physical effects [24, 28, 36, 40]. In three of these studies, 30–32% of PCPs reported "somewhat or good” knowledge of physical effects [24, 28, 36]. Overall, between 10-37% of PCPs reported (high) confidence in providing care for physical effects (n = 8) [21, 22, 32, 37, 39, 40, 49, 51]. Confidence was rated differently for specific physical effects [26, 38], for example 79% of PCPs felt confident in managing fatigue, whereas only 16% felt confident in managing chemobrain [26].

Surveillance and management of psychosocial effects

None of the included studies measured knowledge of psychosocial effects. Seven studies examined PCPs’ confidence in the management of psychosocial effects [21, 26, 32, 37, 40, 49]. In general, a greater proportion of PCPs were confident in managing psychosocial effects than physical effects. Between 24 and 47% of PCPs felt very confident or prepared to manage psychosocial symptoms and adverse effects [21, 32, 37, 40, 49]. In the study by Berry-Stoelzle et al., in which a 4-point Likert scale was reduced into “confident” vs. “not confident”, almost 100% of PCPs were confident in managing depression, anxiety and sleep disturbances [26]. In a different study, PCPs reported overall “good/adequate” confidence in managing anxiety or fear of recurrence (0.97 on a scale of 1.0) [38]. Notably, one study reported high confidence in managing psychological symptoms (47%), but low confidence in providing advice concerning work and/or finances (19%) [40].

Surveillance and management of chronic medical conditions

Three studies examined confidence and comfort in managing chronic medical conditions [27, 31, 51]. None reported knowledge. One study showed high comfort in prescribing medications for cardiometabolic and psychiatric comorbidities in patients with cancer [27]. Another study showed high confidence in managing general medical issues (77%), but much lower confidence in managing cancer-related medical issues (13%) [31]. In the study by Stephens et al., 41% felt very confident to address chronic comorbidities [51].

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Three studies investigated health promotion and disease prevention [32, 38, 40]. None reported knowledge. Between 51 and 57% of PCPs felt very prepared to provide routine age-appropriate preventive care and vaccinations [32]. In two different studies, PCPs reported good confidence in providing lifestyle recommendations [38, 40].

Knowledge barriers and educational needs

Several quantitative studies highlighted the need for education and training on survivorship care issues (n = 9) [19, 20, 25, 28, 30,31,32, 35, 40]. These other outcomes can be found in Supplementary file 3. Inadequate or lack of formal training was reported by up to 72% of PCPs (n = 5) [19, 20, 25, 30, 32]. Three studies also described the educational needs of PCPs [28, 30, 40]. In the study by Walter et al., there was a great desire for education on physical effects following cancer treatment (76–86%), but to a lesser extent on psychosocial effects (36-52%) [40].

Qualitative outcomes

Of the included qualitative studies, some specifically aimed to describe knowledge and confidence in care (n = 5) [43,44,45, 47, 51], while others described it secondary to their aim (n = 5) [41, 42, 46, 48, 49]. Many studies described a lack of knowledge to provide survivorship care (n = 9) [41, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49, 51]. PCPs felt that they need to be educated regarding the follow-up plan/surveillance guidelines, including the interpretation of follow-up test results (n = 4) [41, 43, 44, 49], but also potential late effects of therapy (n = 3) [41, 47, 51]. Three studies mentioned insufficient knowledge of PCPs in work regulations and addressing financial burden of cancer patients [40, 46, 48]. Two different studies showed that lack of knowledge, and therefore lower confidence levels, depended on the cancer survivor population of interest, in this case childhood cancer survivors [45] and older breast cancer patients (≥65 years) [51]. Some PCPs felt well-prepared to provide survivorship care and subsequently confident to do so [42,43,44, 47, 50]. One study indicated that this confidence was grounded in the “wide experience of managing different cancers and chronic conditions other than cancer” [43]. All qualitative outcomes can be found in Supplementary file 4.

Discussion

Our systematic review found 33 studies on self-reported knowledge and confidence of PCPs in providing cancer survivorship care, of which most focused on the management of physical (n = 19) and psychosocial effects (n = 12), and the prevention and surveillance for recurrences and new cancers (n = 14). Overall, a greater proportion of PCPs were confident in managing psychosocial effects after cancer (24–47%) [21, 32, 37, 40, 49] than physical effects (10–37%) [21, 22, 32, 37, 39, 40, 49, 51]. More PCPs reported having the knowledge, specifically skills, in initiating screening and detection of recurrences (62–78%) [21,22,23, 34, 49], than in providing routine follow-up care for cancer survivors (41-59%) [21, 22, 35, 49]. Even fewer PCPs felt very confident, or prepared, to provide routine follow-up care and detect recurrences (6–42%) [21, 29, 31, 32, 34, 49]. Knowledge of cancer surveillance guidelines, and the need to be educated on it, was mentioned in multiple studies [28, 31, 33, 36, 39, 41, 43, 44, 49]. While prior reviews addressed attitudes and preferences to provide cancer survivorship care [7, 9,10,11], to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to specifically delineate PCPs’ knowledge and confidence in cancer survivorship care. Lack of knowledge and expertise of PCPs is mentioned in all reviews as a barrier to provide survivorship care for cancer patients [7, 9,10,11]. However, none of these previous reviews have focused specifically on the PCPs’ knowledge and confidence to provide survivorship care. A recent scoping review by Hayes et al. showed that the perceived lack of knowledge is more prevalent among PCPs, than specialists or cancer survivors [8]. Even though PCPs generally reported good or adequate skills in detecting recurrences [21,22,23, 34, 49] and providing follow-up care [21, 22, 35, 49], their confidence to do so was rated much lower than their knowledge [21, 29, 31, 32, 34, 49]. While our study did not address these factors, others have found lower confidence levels related to fewer (years of) experience [26, 31,32,33,34, 38, 39] and female sex [26, 30, 33, 39]. Confidence may also be related to the cancer survivor population of interest [29, 45, 51] as PCPs may only see a limited number of patients with particular types of cancer.

Previous reviews have indicated the need for additional education and training of PCPs on survivorship care issues [7,8,9,10,11]. A previous review by Chan et al. showed that survivorship education programs help increase knowledge and confidence [16] and assessed the domains of care that were included in such programs. Interestingly, the review found that educational programs tended to focus on physical and psychological effects, as well as cancer recurrence. These findings suggest that despite the attention being placed on these areas of cancer survivorship care, gaps in knowledge and confidence remain. Our study may help to inform future educational programs for PCPs, specifically focusing on managing the physical effects and prevention and surveillance for recurrences. Some studies highlighted the need for PCP education on addressing work and/or financial consequences of cancer treatment for patients [40, 46, 48]. While it is important for PCPs to understand these issues, it is not clear to what extent they feel willing and/or capable of addressing such concerns. We also found a lack of studies addressing knowledge and confidence in the management of chronic medical conditions and health promotion and disease prevention in cancer survivors. It is possible that when conducting research in this area, investigators have chosen to focus on cancer-specific domains rather than those that are already mainly addressed in primary care. However, primary care, with its holistic approach, has an important role in addressing these domains [52,53,54]. Focus on these domains in a PCP-led model could potentially improve outcomes of cancer survivors [53], particularly those who are older and have chronic medical conditions. It is important to emphasize that the educational programs that tackle the gaps in PCPs knowledge and confidence incorporate adult learning theory principles, including behavior change, in order to promote more tangible and sustainable changes in clinical practice [16]. In addition to educational programs, our study adds insights into the potential role of the PCPs in cancer survivorship care and the need for focused interventions in clinical practice. While PCPs appear willing to provide survivorship care [7], divergent views exist regarding the potential role of the PCP. Even though most PCPs believe that cancer survivorship care is within their purview, others consider follow-up after cancer the responsibility of the oncology specialist [11, 55]. These views are likely to depend on the context and setting in which survivorship care takes place. Most papers in our analyses originated from the USA in which survivorship care still relies mainly on oncology specialists’ expertise, despite ongoing efforts to bring survivorship care to the forefront of primary care [56]. In other countries, such as Canada, PCP-led care is more common and widely accepted [57]. This illustrates that further integration of survivorship care in primary care is possible. While we did not specifically address communication and coordination of care with oncology providers in our study, these factors are among the frequently reported barriers to the provision of quality care [7,8,9,10,11]. Interventions targeting communication regarding management of physical effects and surveillance for recurrences, using electronic health records or survivorship care plans, for example, may enhance PCPs knowledge and confidence.

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, most papers originated from the USA (n = 20), which may limit the generalizability of the results to other countries with different healthcare systems. Second, as described earlier, PCPs’ involvement, education and experience with cancer survivorship care differ around the globe. This is likely to affect PCPs’ self-reported knowledge and confidence to provide such care. Participation rates of the surveyed populations varied greatly (14.9 to 65.1%) which could further have an impact on the generalizability. PCPs working in rural areas were underrepresented in the included studies but are likely to have different experience in providing care for cancer survivors than those working in (sub)urban areas. Third, most of the included studies had multiple aims, and measuring knowledge and confidence was often just a small part of those aims. While we focused on knowledge and confidence, maintaining to strict study definitions, the terminology used by the included studies varied. Studies more often focused on confidence in care, than knowledge per se. Future studies should therefore include both outcomes, to help us understand how these two interrelate. It is also important to apply universally-agreed upon terminology to make sure that these studies measure the same outcomes and are consistent. This will permit comparison across populations and interventions [58]. Furthermore, because we specifically focused on physicians’ self-reported data, we excluded 16 studies that did not report these data separately from the other members of the primary care team, such as advance practice clinicians and nurses (Fig. 1), who play an important role in caring for cancer survivors. However, these excluded papers still contain relevant information, and likely provide further information on the knowledge and confidence of other primary care team members. Finally, of the 33 papers, 7 used data from the same 2 studies. Even though the sample sizes and reported outcomes differed in the follow-up papers of the same datasets [19,20,21,22,23,24,25], there is likely overlap. However, as we are not conducting meta-analyses, we do not believe that this has important implications on our findings. Despite the limitations, our study adds to the existing literature by including quantitative and qualitative studies, and by characterizing the outcomes by cancer care domains, using previously applied methodology [6, 16,17,18].

In summary, our study found that PCPs’ self-reported knowledge and confidence in cancer survivorship care varies across the care domains and is specifically limited in management of physical effects and prevention/surveillance for recurrences and new cancers. These results provide insights into the potential role of PCPs in cancer survivorship care, and the development of future educational programs medical education and targeted interventions.

Data availability

All data abstracted and analyzed during the review process are included in the article and its supplementary files.

References

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobsen PB, Mayer DK, Shulman LN, Geiger AM. Developing a quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework: Implications for Clinical Care, Research, and Policy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(11):1120–30.

Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Supportive Care Cancer. 2009;17(8):1117–28.

Hart NH, Crawford-Williams F, Crichton M, Yee J, Smith TJ, Koczwara B, et al. Unmet supportive care needs of people with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a systematic scoping review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022;176:103728.

Jefford M, Howell D, Li Q, Lisy K, Maher J, Alfano CM, et al. Improved models of care for cancer survivors. Lancet. 2022;399(10334):1551–60.

Chan RJ, Crawford-Williams F, Crichton M, Joseph R, Hart NH, Milley K, et al. Effectiveness and implementation of models of cancer survivorship care: an overview of systematic reviews. J Cancer Surviv. 2021:1–25.

Meiklejohn JA, Mimery A, Martin JH, Bailie R, Garvey G, Walpole ET, et al. The role of the GP in follow-up cancer care: a systematic literature review. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6):990–1011.

Hayes BD, Young HG, Atrchian S, Vis-Dunbar M, Stork MJ, Pandher S, et al. Primary care provider–led cancer survivorship care in the first 5 years following initial cancer treatment: a scoping review of the barriers and solutions to implementation. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;

Lawrence RA, McLoone JK, Wakefield CE, Cohn RJ. Primary Care physicians’ perspectives of their role in cancer care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1222–36.

Love M, Debay M, Hudley AC, Sorsby T, Lucero L, Miller S, et al. Cancer Survivors, oncology, and primary care perspectives on survivorship care: an integrative review. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13:21501319221105248.

Lewis RA, Neal RD, Hendry M, France B, Williams NH, Russell D, et al. Patients’ and healthcare professionals’ views of cancer follow-up: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(564):e248–59.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Lisy K, Mu P-F. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179–87.

Chan RJ, Agbejule OA, Yates PM, Emery J, Jefford M, Koczwara B, et al. Outcomes of cancer survivorship education and training for primary care providers: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;16(2):279–302.

Margalit DN, Salz T, Venchiarutti R, Milley K, McNamara M, Chima S, et al. Interventions for head and neck cancer survivors: systematic review. Head Neck. 2022;44(11):2579–99.

Kemp EB, Geerse OP, Knowles R, Woodman R, Mohammadi L, Nekhlyudov L, et al. Mapping Systematic reviews of breast cancer survivorship interventions: a network analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(19):2083–93.

Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, Park ER, Kutner JS, Najita JS, et al. Caring for cancer survivors: a survey of primary care physicians. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4409–18.

Park ER, Bober SL, Campbell EG, Recklitis CJ, Kutner JS, Diller L. General internist communication about sexual function with cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S407–S11.

Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, Klabunde CN, Smith T, Aziz N, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1403–10.

Cheung WY, Aziz N, Noone A-M, Rowland JH, Potosky AL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Physician preferences and attitudes regarding different models of cancer survivorship care: a comparison of primary care providers and oncologists. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):343–54.

Klabunde CN, Han PK, Earle CC, Smith T, Ayanian JZ, Lee R, et al. Physician roles in the cancer-related follow-up care of cancer survivors. Fam Med. 2013;45(7):463–74.

Nekhlyudov L, Aziz NM, Lerro C, Virgo KS. Oncologists’ and primary care physicians’ awareness of late and long-term effects of chemotherapy: implications for care of the growing population of survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(2):e29–36.

Virgo KS, Lerro CC, Klabunde CN, Earle C, Ganz PA. Barriers to breast and colorectal cancer survivorship care: perceptions of primary care physicians and medical oncologists in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(18):2322–36.

Berry-Stoelzle M, Parang K, Daly J. Rural Primary Care Offices and Cancer Survivorship Care: Part of the Care Trajectory for Cancer Survivors. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2019;6:2333392818822914.

Chou C, Hohmann NS, Hastings TJ, Li C, McDaniel CC, Maciejewski ML, et al. How comfortable are primary care physicians and oncologists prescribing medications for comorbidities in patients with cancer? Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16(8):1087–94.

Chow R, Saunders K, Burke H, Belanger A, Chow E. Needs assessment of primary care physicians in the management of chronic pain in cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(11):3505–14.

Fidjeland HL, Brekke M, Vistad I. General practitioners’ attitudes toward follow-up after cancer treatment: A cross-sectional questionnaire study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(4):223–32.

Gonzalez Carnero R, Sanchez Nava JG, Canchig Pilicita FE, Gomez Suanes G, Rios German PP. Lopez De Castro F. Training needs in the care of oncological patients. Med Paliativa. 2013;20(3):103–10.

Mani S, Khera N, Rybicki L, Marneni N, Carraway H, Moore H, et al. Primary care physician perspectives on caring for adult survivors of hematologic malignancies and hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020;20(2):70–7.

McDonough AL, Rabin J, Horick N, Lei Y, Chinn G, Campbell EG, et al. Practice, preferences, and practical tips from primary care physicians to improve the care of cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(7):e600–e6.

Nathan PC, Daugherty CK, Wroblewski KE, Kigin ML, Stewart TV, Hlubocky FJ, et al. Family physician preferences and knowledge gaps regarding the care of adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):275–82.

Radhakrishnan A, Reyes-Gastelum D, Hawley ST, Hamilton AS, Ward KC, Wallner LP, et al. Primary care provider involvement in thyroid cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15)

Roorda C, Berendsen AJ, Haverkamp M, van der Meer K, de Bock GH. Discharge of breast cancer patients to primary care at the end of hospital follow-up: a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(8):1836–44.

Sima JL, Perkins SM, Haggstrom DA. Primary care physician perceptions of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36(2):118–24.

Skolarus TA, Holmes-Rovner M, Northouse LL, Fagerlin A, Garlinghouse C, Demers RY, et al. Primary care perspectives on prostate cancer survivorship: implications for improving quality of care. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(6):727–32.

Smith SL, Wai ES, Alexander C, Singh-Carlson S. Caring for survivors of breast cancer: perspective of the primary care physician. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(5):e218–e26.

Suh E, Daugherty CK, Wroblewski K, Lee H, Kigin ML, Rasinski KA, et al. General internists’ preferences and knowledge about the care of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(1):11–7.

Walter FM, Usher-Smith JA, Yadlapalli S, Watson E. Caring for people living with, and beyond, cancer: an online survey of GPs in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(640):e761–e8.

Duffey-Lind EC, O’Holleran E, Healey M, Vettese M, Diller L, Park ER. Transitioning to survivorship: a pilot study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2006;23(6):335–43.

Fox J, Thamm C, Mitchell G, Emery J, Rhee J, Hart NH, et al. Cancer survivorship care and general practice: a qualitative study of roles of general practice team members in australia. Health Soc Care Community. 2021;30(4):e1415–26.

Margariti C, Gannon KN, Walsh JJ, Green JSA. GP experience and understandings of providing follow-up care in prostate cancer survivors in England. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28(5):1468–78.

Radhakrishnan A, Henry J, Zhu K, Hawley ST, Hollenbeck BK, Hofer T, et al. Determinants of quality prostate cancer survivorship care across the primary and specialty care interface: Lessons from the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer Med. 2019;8(5):2686–702.

Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, Fardell JE, Foreman T, Johnston KA, Emery J, et al. The role of primary care physicians in childhood cancer survivorship care: multiperspective interviews. Oncologist. 2019;24(5):710–9.

Thamm C, Fox J, Hart NH, Rhee J, Koczwara B, Emery J, et al. Exploring the role of general practitioners in addressing financial toxicity in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(1):457–64.

Vos JAM, de Best R, Duineveld LAM, van Weert H, van Asselt KM. Delivering colon cancer survivorship care in primary care; a qualitative study on the experiences of general practitioners. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):13.

Sarfo MC, Bertels L, Frings-Dresen MHW, de Jong F, Blankenstein AH, van Asselt KM, et al. The role of general practitioners in the work guidance of cancer patients: views of general practitioners and occupational physicians. J Cancer Surviv. 2022:1–9.

Dawes AJ, Hemmelgarn M, Nguyen DK, Sacks GD, Clayton SM, Cope JR, et al. Are primary care providers prepared to care for survivors of breast cancer in the safety net? Cancer. 2015;121(8):1249–56.

Heins M, Korevaar J, Van Dulmen S, Donker G, Schellevis F. Feasibility and acceptability of follow-up care for prostate cancer in primary care. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72(Supplement 1):S186.

Stephens C, Klemanski D, Lustberg MB, Noonan AM, Brill S, Krok-Schoen JL. Primary care physician’s confidence and coordination regarding the survivorship care for older breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(1):223–30.

Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM, Dommett R, Earle C, Emery J, et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(12):1231–72.

Adam R, Watson E. The role of primary care in supporting patients living with and beyond cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2018;12(3):261–7.

Nekhlyudov L, Snow C, Knelson LP, Dibble KE, Alfano CM, Partridge AH. Primary care providers’ comfort in caring for cancer survivors: Implications for risk-stratified care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023;70(4):e30174.

Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Howard J, Rubinstein EB, Tsui J, Hudson SV, et al. Cancer Survivorship care roles for primary care physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(3):202–9.

Rubinstein EB, Miller WL, Hudson SV, Howard J, O’Malley D, Tsui J, et al. Cancer survivorship care in advanced primary care practices: a qualitative study of challenges and opportunities. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1726–32.

Howell D, Hack TF, Oliver TK, Chulak T, Mayo S, Aubin M, et al. Survivorship services for adult cancer populations: a pan-Canadian guideline. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(6):e265–81.

Boulet JR, Durning SJ. What we measure … and what we should measure in medical education. Med Educ. 2019;53(1):86–94.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank F.S. Jamaludin, medical librarian at the Amsterdam UMC, for her help with the search strategy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. A medical librarian (FJ) performed the initial search. Title and abstract screening was performed by two authors JV and BW. Full-text screening, data abstraction and quality appraisal assessment were done by all authors. Data synthesis was done by JV. AC and JV wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was commented on by all other authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 108 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vos, J.A., Wollersheim, B.M., Cooke, A. et al. Primary care physicians’ knowledge and confidence in providing cancer survivorship care: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01397-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01397-y