Abstract

Purpose

Advances in breast cancer care have led to a high rate of survivorship. This meta-review (systematic review of reviews) assesses and synthesises the voluminous qualitative survivorship evidence-base, providing a comprehensive overview of the main themes regarding breast cancer survivorship experiences, and areas requiring further investigation.

Methods

Sixteen breast cancer reviews identified by a previous mixed cancer survivorship meta-review were included, with additional reviews published between 1998 and 2020, and primary papers published after the last comprehensive systematic review between 2018 and 2020, identified via database searches (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO). Quality was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative) checklist for primary studies. A meta-ethnographic approach was used to synthesise data.

Results

Of 1673 review titles retrieved, 9 additional reviews were eligible (25 reviews included in total). Additionally, 76 individual papers were eligible from 2273 unique papers. Reviews and studies commonly focused on specific survivorship groups (including those from ethnic minorities, younger/older, or with metastatic/advanced disease), and topics (including return to work). Eight themes emerged: (1) Ongoing impact and search for normalcy, (2) Uncertainty, (3) Identity: Loss and change, (4) Isolation and being misunderstood, (5) Posttraumatic growth, (6) Return to work, (7) Quality of care, and (8) Support needs and coping strategies.

Conclusions

Breast cancer survivors continue to face challenges and require interventions to address these.

Implications for Cancer Survivors.

Breast cancer survivors may need to prepare for ongoing psychosocial challenges in survivorship and proactively seek support to overcome these.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC), while highly prevalent globally (highest incidence cancer among women in 159/185 countries) [1], has a high survival rateThe average five-year survival rate in Australia for BC from 2013 to 2017 was 91.5%, compared to 69.7% for all cancer types combined [2]. Cancer survivors are defined as individuals diagnosed with cancer who have completed their initial cancer treatment [3], including those considered cured and those living with ‘advanced’ disease (including locally advanced and metastatic cancer), receiving ongoing care.

BC survivors may experience significant long-term psychosocial effects that impact their quality of life, including fatigue, pain, difficulty sleeping, cognitive challenges, sexual dysfunction, depression, anxiety and fear of recurrence or progression [4,5,6,7]. Women with advanced BC may additionally experience feelings of abandonment, isolation, existential distress and a loss of control [4, 8, 9]. Thus, BC survivors may benefit from tailored support and care [4, 8].

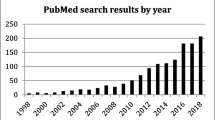

To inform development of BC survivorship services, a comprehensive understanding of women’s experiences and needs is required. Qualitative research, which captures women’s lived experiences, is well placed to provide that understanding [10]. The number of qualitative studies focusing on BC survivorship has steadily increased since the late 1990s (see Fig. 1). Systematic reviews which aim to critically appraise and summarise the findings of these primary studies have also increased. While systematic reviews provide a high level of evidence to inform research and policy [11, 12], many BC survivorship systematic reviews focus on specific topics (for example, return to work [13]) or populations (for example, women from a particular ethnicity [14]). To provide a more complete picture of the evidence base and identify areas of research density/paucity, a meta-review (systematic review of systematic reviews) is required. Meta-reviews can synthesise entire fields of research and are particularly beneficial when there is a large evidence base on a topic [12]. Such an overview is required firstly to ensure that new research investigates areas where data are lacking, and secondly to guide BC health professionals in their provision of care, particularly within survivorship centres which focus on this phase of the disease.

To date, one meta-review of qualitative cancer survivorship studies has been conducted [15]. Laidsaar-Powell et al.’s [15] meta-review of 60 qualitative systematic reviews conducted between 1998 and 2018 included 19 reviews addressing BC survivorship. However, due to its wide scope, no specific detail was provided about BC survivorship, and systematic reviews focused on advanced BC were not included. Furthermore, new systematic reviews and primary qualitative studies focused on BC survivorship have been published since 2018. Thus, the current study aimed to conduct an extensivemeta-review of qualitative BC systematic reviews supplemented by a systematic review of primary qualitative studies conducted since the last SR search-date. This BC meta-review aims to provide the first truly comprehensive and exhaustive summary of qualitative evidence focusing on survivorship experiences of women with BC, across both early and advanced stage disease.

Methods

Search strategy

This meta-review and systematic review followed Smith et al.’s [12] meta-review guidelines, and adhered to a predefined protocol registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration #CRD42021258728, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021258728). BC survivorship reviews identified in Laidsaar-Powell et al.’s [15] original meta-review (n = 19) were examined for eligibility. Three literature searches were conducted via electronic databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO). Search 1 identified systematic reviews published between May 2018 (the latest date searched by Laidsaar-Powell et al. [15]) and August 2020 (the date of this search), used the keywords: (breast cancer) AND (survivor* OR post-treatment) AND (qualitative OR experience OR thematic analysis OR interviews OR focus groups) AND (review OR synthesis OR summary). Search 2 conducted in October 2020, identified systematic reviews focusing on advanced BC survivorship. This search did not restrict publication date. It used the same search terms, replacing the keywords: (survivor* OR post-treatment) with (advanced OR metastatic OR late stage). Search 3 conducted in February 2021, focused on primary papers published since the last search conducted for an eligible comprehensive systematic review (January 2018), using the same search terms, but omitting the terms (review OR synthesis OR summary). Search results were imported into Covidence reviewsoftware [16], with duplicates deleted. Study selection, data extraction and bias assessment were undertaken by one author (RK), with 20% independently reviewed by a second reviewer to check accuracy; disagreements were resolved through consensus and discussion with the wider research team.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Systematic reviews/papers were included if they were published in English in peer-reviewed journals, and reported qualitative findings relating to BC survivorship experiences. Letters to the editor, conference abstracts, commentaries, and case studies were excluded. Reviews /papers focused on end-of-life/palliative care, caregivers, practitioners, paediatrics/adolescents (i.e. under 18 years of age), or patients currently undergoing or yet to undergo initial treatment, or which focused on service provision, interventions or treatment evaluations, were excluded. Reviews/papers reporting both qualitative and quantitative results or multiple populations (e.g. survivors and patients) were included provided qualitative survivorship findings were reported separately and in sufficient detail to be extracted. Initially, titles and abstracts, then eligible or potentially eligible full-texts, were reviewed for evaluation against eligibility criteria.

Data extraction and bias assessment

Data were extracted onto a study-designed form (see Tables 1 and 2). The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Synthesis [11] and the Qualitative Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [17] were used for bias assessment (see Supplementary Table 1 and 2 for checklist items). One item for systematic reviews (‘was the likelihood of publication bias assessed?’) was excluded, as it primarily relates to quantitative findings. Each review/paper received a score out of 10 derived from the 10 applicable items (scored as 1 = yes or not applicable, and 0 = no or unclear), with higher scores indicating better quality.

Data synthesis and interpretation

Thematic synthesis was conducted by RK, in consultation with the broader research team, whereby iterative revisions of themes and categories were discussed until consensus was reached. A meta-ethnographic approach [18] was used, including (1) extraction of findings from included reviews/papers, with an accompanying quote; (2) development of categories for findings where there are at least two examples; and (3) development of higher order categories. Categorisation involved repeated, detailed examination of assembled findings for similarity in meaning.

Results

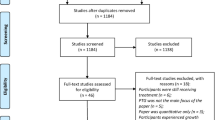

Figure 2 describes the study selection process guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [19]. Three of the 19 Laidsaar-Powell et al. [15] BC reviews were excluded as they contained very limited qualitative BC findings. After deletion of duplicates and eligibility screening, 25 systematic reviews were included in this meta-review (including 7 from Search 1 and 2 from Search 2), with an additional 76 primary papers.

Study characteristics

Eight systematic reviews included qualitative studies only and 17 included mixed methods studies. Fourteen (56%) reviews were published in the past five years (2016–2020), reflecting the recent increase in BC survivorship research (see Fig. 3). Of the papers, only three were mixed methods.

Three systematic reviews focused completely or partially on metastatic/advanced BC [5, 20, 21]. Five reviews focused on ethnic minorities including African American [14, 22, 23], Asian American [24], and Korean American [25] women. Two reviews focused on rural BC survivors [26, 27] and three focused completely or partially on age (i.e. younger and older BC survivors) [28,29,30]. Some reviews had a broad focus on BC survivorship and psychosocial needs, while others covered specific topics including return to work [13, 31,32,33,34], cognitive difficulties [34, 35], adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy [36], pain [37], spirituality [20], parenthood [38], and sexual functioning [29].

Seven papers focused on metastatic BC [39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Five focused on African American survivors [46,47,48,49,50], eleven on ‘younger’ survivors (e.g. under 50 years) [41, 43, 49, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58], nine on return to work [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67], two on cognitive difficulties [68, 69], four on lymphoedema [65, 70,71,72], four on cancer-related fatigue [73,74,75,76], five on sexual and/or reproductive health [51, 58, 77,78,79], and four on healthy lifestyle factors (i.e. nutrition and exercise) [45, 54, 80, 81]. Other populations/topics explored included low SES survivors [39, 82], sexuality and gender diverse survivors [83], infant feeding [84], healthcare experience [85,86,87], economic burden [71], parenthood [88], posttraumatic growth [89], fear of recurrence [90,91,92], adjuvant endocrine therapy persistence/management [93, 94], and religion/spirituality [94]. Other papers had a wider scope, exploring BC survivors’ experiences and psychosocial needs.

Quality assessment

See Tables 1 and 2 for an overview of the methodological quality of included reviews/papers. Six systematic reviews received a score of 10/10, indicating high methodological quality. Most reviews (12) scored in the moderate quality range (7–9/10). Seven SRs scored 5–6/10, indicating limited methodological quality. Items F (‘was critical appraisal conducted by two or more reviewers independently?’) and G (‘were there methods to minimise errors in data extraction?’) were the two most unmet items.

Fourteen papers received a score of 10/10. Most papers (60) scored in the moderate quality range (7–9/10). Two papers scored 4–6/10, indicating limited methodological quality. Item F (‘has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?’) was the most unmet item.

Thematic analysis

From the included reviews/papers, 8 over-arching themes were identified: (1) Ongoing impact and search for normalcy, (2) Uncertainty, (3) Identity: Loss and change, (4) Isolation and being misunderstood, (5) Posttraumatic growth, (6) Return to work, (7) Quality of care, and (8) Support needs and coping strategies. These themes are presented with subthemes and participant quotes selected from systematic reviews (reviews) and primary papers (papers), where appropriate.

Theme 1: Ongoing impact and search for normalcy

“Am I healthy or am I not”?

The ongoing impact of BC and its treatment came as a shock to many women as they transitioned into survivorship [36]. Many systematic reviews examined the impact of ongoing symptoms on survivorship, including persistent pain, fatigue and weakness, feeling unwell, sleeping difficulties, lymphoedema, impaired cognition (including ‘chemobrain’), skin conditions, menopausal symptoms, sexual problems, and fertility issues [5, 13, 21, 22, 29, 33,34,35,36,37], as did primary papers (PPs) [41, 44, 49, 51, 52, 55, 68,69,70, 73,74,75,76, 79, 84, 85, 95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102]. These ongoing side-effects challenged expectations that after treatment, BC survivors would return to their premorbid level of health. Instead, survivors found themselves in a space between illness and health [Review: [37]].

Physical and cognitive symptoms led to significant limitations that impacted daily life (e.g. inability to clean or drive), as well as impairing social, occupational, and physical activities [Reviews: [5, 13, 21, 33, 34, 36, 37]; Papers [44, 70, 95, 96]].

Some survivors reported feelings of desperation and fatalism that their symptoms would never improve [Review: [37]].

Sometimes when I wake up I think ‘will the pain be like this every day, always, always…’ that's hard to manage sometimes [Review: [37]]

Due to the significant impact of persistent side-effects, some survivors began to value their quality of life (QOL) (i.e. symptom management) over length of life [Review: [36]]. For example, some BC survivors chose to cease adjuvant treatment designed to prevent recurrence and prolong life, to reduce debilitating side-effects and increase quality of life [Review: [36]; Paper: [93]].

I said, I’ve had tamoxifen, and I’ve had breast cancer. I would rather have breast cancer [Review: [36]]

I chose a lesser time left. I said at my age, does it matter if the cancer comes back one way or another… I like my home and I like being involved in the community, going to the club and that. Coming off the tablet has given me back that quality of life [Review: [36]].

Psychological impact

BC survivors also experienced psychological problems due to enduring side-effects, ongoing uncertainty and concern about the future. They expressed feelings of sadness, shock, guilt, insecurity, worry, anger, fear, disappointment, distress, and grief [Reviews: [5, 21, 28, 29, 33]; Papers: [41, 49, 52, 55, 57, 68, 70, 74, 75, 79, 96,97,98,99, 102,103,104]], especially those experiencing recurrence [Review [5]:].

It [BC recurrence] was such a dreadful disappointment that I got a feeling that it didn’t matter what I did. That little devil who has sunk his claws into me isn’t going to let go… the disappointment was enormous [Review [5]:]

“Things will never be normal, and that’s awful”

Many survivors sought normalcy after treatment: a return to pre-cancer health and ability [Reviews: [5, 13, 21, 22, 28, 36]; Papers: [95, 97, 100, 105, 106]]. Re-establishing normalcy involved adjusting daily activities to match limitations, focusing on relationships, and not focusing on the BC [Review: [21]; Paper: [69]]. Additionally, women attempted to rebuild their pre-treatment lives (and identity) to re-establish normalcy, including returning to work [Review: [13]]. For some, a return to normalcy was perceived as impossible. Significant changes to the body (e.g. scarring, menopausal symptoms, physical and cognitive impairment) and to lives (e.g. career and relational disruptions) made the life that women once had, or imagined for their future, impossible to reach [Review: [28]; Papers: [70, 107]. Recurrence exacerbated this sense of loss [Review: [5]].

Theme 2: Uncertainty

Patient to survivor

BC survivors underwent a transition from undergoing primary treatment (being a patient) to life post-treatment (survivorship) and this transition was characterised by uncertainty regarding future quality and length of life [Reviews: [28, 37, 108]; Papers: [91, 96, 109, 110]]. This uncertainty was exacerbated by decreased support from and contact with health providers and other patients, as women shifted to self-management while losing the hospital ‘safety net’ [Reviews: [14, 37, 108]; Papers [60, 85, 96, 100]:].

The problems start after that [end of treatment]: whom do you turn to when you have pain in your hip like I do? [Review: [37]]

Uncertainty of symptoms

BC survivors experienced uncertainty and worry related to ongoing symptoms and need for further treatment (e.g. ongoing adjuvant treatment) [Reviews: [34, 36, 108]; Papers: [48, 109]]. One review noted survivors were unsure about the likely duration of ongoing cognitive impairment, which was compounded by a lack of information about their symptoms [Review: [34]].

Fear of recurrence and death anxiety

The transition into survivorship and loss of regular contact with the treatment team heightened many women’s fears of cancer recurrence (FCR) [Review: [14]]. FCR, recently defined as “fear, worry or concern relating to the possibility that cancer will come back or progress” (p. 3266)[111], was a common and significant issue for survivors [Reviews: [28, 30, 36,37,38, 108]; Papers: [52, 55,56,57, 82, 90,91,92, 99, 101, 109, 110, 112]]. FCR focused women on the uncertainty of their future [Review: [5]].

One of my biggest fears is the 5-year waiting period, to find out if we are going to survive or not. That creates suspense, fear, and negative emotions… I feel like I’m standing on a balance just waiting to see which way it is going to go [Review: [5]].

The furthest I can think is the coming weeks and months. I don't make long-term plans [Review: [5]]

FCR can lead to excessive vigilance regarding symptoms. While some degree of symptom monitoring is required for early detection of recurrence if it occurs, hypervigilance can lead to ongoing and exacerbated fears and anxiety. Many women had difficulty determining what is ‘normal’ and what may be a sign of recurrence [Reviews: [37, 108]; Paper: [52]].

You really listen to your body in quite a different way now. Every little thing you feel in your body could be signs of something abnormal [Review: [37]]

Women with metastatic BC were particularly hyper-vigilant while monitoring for signs of disease progression [Reviews: [5, 21]]. The need for symptom monitoring and the possibility of recurrence meant the survivorship period had no certain endpoint [Review: [108]].

“My time’s running out”

Reviews found a preoccupation with death in BC survivors [Reviews: [28, 37]], particularly in survivors with advanced BC [Reviews: [5, 20, 21]]. For some women, this led to a sense of urgency to live life to the full, leaving them out of step with friends and family [Review: [37]; Paper: [41]].

It felt like everyone was driving too slowly and I didn't have the time to sit there and wait… I felt like ‘you have all the time in the world, but my time's running out’ [Review: [37]].

Younger women coped with thoughts of death by attempting to have some control over the process through communicating their dying wishes, while mothers coped by making plans to ensure their children would be well cared for [Review: [28]]. However, not everyone feared death, as was found for some survivors with advanced BC [Review: [5]].

I've kind of come to terms with these fears, and I'm not really afraid of dying [Review: [5]]

Theme 3: Identity: loss and change

“I’m different… I’m imperfect”

Bodily changes due to BC and its treatment (including loss of hair and one or both breasts), meant that many women were persistently reminded of their cancer due to an altered body image. Some felt a loss of control and alienated from their bodies, disfigured and undesirable, with a changed identity [Reviews: [5, 14, 21, 22, 28, 29, 113]; Papers: [48, 51, 53, 70, 78, 95, 98, 99, 101, 103, 104, 110, 112, 114]]. However, some survivors did not experience body image disturbances or were able to adapt to changes over time [Papers: [53, 110]], even viewing their scars as positive signs they were disease-free [Review: [113]].

Each time I passed a mirror I jumped back because I didn't recognise myself [Review: [5]]

I'm different from those who are normal… For myself, I'm imperfect. I had the surgery and lost one side [of the breast] [Review: [113]]

I saw myself and I felt bad they had taken my breast. But then, I said, `No. Thank God. Because it was taken, I live.' Then I was assimilating, and now it's normal for me, that I don't have my chest [Paper: [53]].

For some women, losing a breast led to changes in their sense of femininity and womanhood [Review: [113]].

… you started discovering that you were now just half a woman ‐ my femininity disappeared… [Review: [113]]

In reviews focusing on African American BC survivors, hair loss from treatment (and changes to hair texture and colour), as well as body altering surgeries, left women feeling damaged and less feminine and this was amplified by a desire to appear strong and to look well [Reviews: [14, 22]].

Sexuality and relationships: “I felt something was missing”

The impact of BC treatment on women’s bodies also affected sexuality and intimate relationships [Reviews: [5, 21, 22, 29, 113]; Papers: [53, 58, 76,77,78,79, 95,96,97]]. Insecurities after mastectomy reduced women’s sense of sexual desirability [Reviews: [5, 22, 113]; Paper: [77]].

The majority of us feel degraded as women as we see ourselves in the mirror and wonder, ‘If we cannot accept ourselves, how can our husbands or partners?’ [Review: [5]]

Other treatment side-effects impacting sexual activity and intimacy included early menopause, pain, vaginal dryness, and reduced sexual desire/libido [Reviews: [22, 29]]. Some women felt rejected by partners due to changes in their relationship [Review: [22]].

Fertility and infertility

Reviews/papers examined association between identity and fertility and how BC and treatments posed a threat to this part of women’s lives [Reviews: [28, 29, 38]; Papers: [52, 53, 88, 96]]. For some women, especially pre-menopausal women, loss and grief related to infertility was significant and served as an emotional reminder of BC [Review: [28]]. For other survivors, a pregnancy post-cancer was considered restorative and normalising [Paper: [84]].

To have something grow inside you on purpose in contrast to this cancer that grew unwelcome… you’re trusting in your body again…It felt just so normal [Paper: [84]]

Fertility, for others, was viewed as secondary to survival and preventing recurrence [Review: [38]]. While some women desired children in the future, others decided against children due to FCR, genetic risk and the health of the baby [Review: [38]].

Changing and maintaining roles

For many survivors, there was a significant shift in roles and relationships, from providing to receiving care [Reviews: [22, 25, 28, 108]; Paper: [76]]. There was also a desire (and sometimes expectation from others) to maintain identity and normalcy by fulfilling former roles, such as upholding the role of homemaker [Review: [34]], returning to work [Review: [13]], or caregiving [Reviews: [25, 28]; Papers: [39, 43, 114]]. For some women, however, this expectation to fulfil their pre-diagnosis role was a challenge and burden [Review: [25]].

Even after getting chemo, I still had to take care of my children, so that was hard [Review: [25]]

Theme 4: Isolation and being misunderstood

Limitations and stigmatisation meant some survivors isolated themselves or felt unable to fully participate in social life, consequently reducing the social support available to them [Reviews: [21, 113]; Papers: [44, 48, 72, 74, 90, 103]]. Some survivors, especially older survivors, reported not wanting to burden those around them [Reviews: [25, 28]; Paper: [90]]. Many also felt misunderstood by others (including family, community and co-workers) as they struggled with ongoing challenges from their diagnosis and treatment. Survivors described an unrealistic expectation from those around them that they would fully recover and be symptom-free after primary treatment [Reviews: [13, 14, 25, 32, 34, 37]; Papers: [56, 107]], especially when they may appear physically well to others [Paper: [43]].

Families don’t understand. They say they understand, but they expect us to be the same people as before the disease [Review: [25]]

That’s one of the things that people don’t understand about having stage IV cancer. I think a lot of people think [your] appearance should be bald and super thin and kind of sickly looking. When I tell people, “I’ll always have stage IV cancer,” they look at me. “No, you don’t.” I’m like, “I look normal, I know.” You can look normal. People don’t realise that [Paper: [43]].

Theme 5: Posttraumatic growth

“To grow from it, to heal from it”

Many reviews/papers identified posttraumatic growth alongside the negative impacts of BC and its treatment [Reviews: [5, 13, 21, 28, 32, 34, 113]; Papers: [39, 48, 55,56,57, 89, 102, 104, 105, 109, 110, 114]]. Some women were able to embrace and accept their new bodies [Reviews: [5, 113]; Paper: [114]].

[Cancer] definitely changed my life… for the better. It gave me more of a clarity about myself… to take it and grow from it, and heal from it, and achieve from it [Paper [39]:]

I like my body better now… I've accepted it so I like my body… it's part of life you know and you just get on with it… [Review: [113]]

‘Wakeup call’

Some survivors also reported a greater appreciation for life and a sense of gratitude, viewing their cancer experience as a turning point and making the most of their lives now [Reviews: [5, 21, 28, 34, 113]; Papers: [39, 57, 102]].

For some, the shift to focusing on appreciating life included a re-evaluation of their work/life balance, [Reviews: [13, 32]; Paper: [55]], working towards personal goals and values, prioritising relationships, and contributing to the community [Reviews: [21, 34]; Papers: [48, 89, 109]]. This included a sense of empowerment through focusing on healthy lifestyle changes and self-management [Papers: [48, 105, 109]]. Finding meaning in the BC experience was realised by connecting with (and supporting) others diagnosed with BC and advocating for increased BC awareness [Reviews: [5, 20, 21, 28]; Papers: [48, 55, 109, 110]].

Theme 6: Return to work

Four reviews specifically focused on the return-to-work experience for BC survivors [Reviews: [13, 31,32,33]], while one review discussed return to work in the context of cognitive changes [Review: [34]]. Employment was also discussed in many primary papers [Papers: [53, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68, 95, 99]]. Returning to work was important to many survivors as a way of regaining a sense of normalcy, meaning, identity, support and connection [Reviews: [13, 32, 34]; Paper: [95]]. However, some survivors found the work environment unsupportive, with some even facing discrimination [Reviews: [31, 32]; Papers: [53, 63]]. Privacy regarding disclosure of illness was an issue; some survivors found that employers did not keep their health status confidential [Review: [32]]. Treatment side effects and body insecurities led to challenges and loss of confidence at work [Reviews: [13, 31, 33]; Papers: [63, 64]].

I had to lean down to do anything on the bottom, lower shelf or even for bags to pack them, I was like this [covered her chest] all the time, holding it together… every minute of my working day you’re thinking of it [Review: [33]].

Some survivors reported cognitive impairments such as problems with concentration, executive function, memory, and speed of processing [Review: [33, 34]; Papers: [63, 68]].

With this memory thing, I was very frustrated at work and so I thought that I can’t go on like this. It was a chore now going to work than a joy [Review: [33]]

Many survivors experienced anxiety and frustration around their capacity to return to work [Reviews: [13, 31,32,33]]. This was further complicated by employers expecting survivors to be as capable post-treatment as they were pre-diagnosis and survivors not wanting to disappoint or mislead them [Reviews: [13, 31, 32]]. Survivors also described financial pressure to return to work [Reviews: [13, 32]].

Theme 7: Quality of care

Health care experiences

Many reviews focused on experience of the health care system as a cancer survivor. While many women reported positive healthcare experiences, some reported negative interactions. AlOmeir et al. [36] reviewed factors influencing survivors’ adherence to adjuvant treatment, finding that the decision to accept or delay treatment was influenced by trust in health care providers as well as concerns, expectations and knowledge of the treatment. Selamat et al.’s [34] review, focused on experience of cognitive changes, found survivors experienced a lack of information about cognitive deficits and felt invalidated and dismissed by health professionals. Some survivors with metastatic BC reported that their needs were not met if care focused on physical symptoms to the exclusion of psychosocial needs [Review: [21]].

Feeling alone; lack of information and support

Survivors noted a need for information about the reality of survivorship and disease management, especially about ongoing side-effects [Reviews: [22, 28, 30, 31, 34, 36, 37]; Papers: [60, 87, 95, 98,99,100, 109]].

Survivors also noted a need for relevant information, empathy and support from health services, otherwise they felt dismissed, unsupported and alone [Reviews: [36, 37]; Papers: [40, 46, 51, 68, 72, 82, 84, 85, 90, 91, 97, 105]].

I wished that my pain at home was followed up much more [Review: [37]]

Barriers

Reviews identified barriers for survivors to access health services. For rural BC survivors, location and transport needs were a barrier to care [Review: [26]]. For some low SES and/or ethnically diverse BC survivors, there were concerns about the quality of care they had access to [Paper: [39]].

It’s a county hospital, so it’s an overly stressed system … They don’t have resources … I was told that in a private institute, you were assigned a nutritionist, a social worker and a binder that had everything broken down … I wish we had a universal medical system and when you get cancer this is what you get [Paper: [39]].

Several primary papers highlighted the ongoing financial burden/barrier associated with BC due to healthcare cost and productivity loss [Papers: [82, 99, 103, 105, 112]], including BC survivors with lymphoedema [Paper: [71]].

I lost my job ‘cause I got diagnosed with breast cancer so financially it was very difficult … I was out of work for almost a year … with the chemo… I was really sick and then I went back against the doctor’s orders ‘cause I needed to make money… When I came back to work that’s when they expected me to resume all of the duties… full force and…I got fired… [Paper: [71]].

Language can also pose a significant challenge when seeking information and support. Wen et al. [Review: [24]] found for Asian American women, communication with health professionals was sometimes challenging. Similarly, survivors struggled to find support groups in their community when there was a language barrier or perceived cultural differences [Review: [25]].

Americans don’t seem to share their emotions with immigrants like us. They don’t try to talk to us first… [Review: [25]]

Theme 8: Support needs and coping strategies

Social support

BC survivors reported needing practical and emotional support from family, partners, friends, community groups, co-workers, other BC survivors and health providers [Reviews: [5, 14, 21,22,23, 25,26,27,28,29, 34, 36, 115]; Papers: [39, 43, 47,48,49, 53,54,55, 68, 69, 74, 78, 82, 84, 95, 97, 99, 105, 109, 112, 114, 116]]. These supports helped survivors to engage in activities, contribute to community, talk about their experiences, and cope with distress [Reviews: [21, 34]]. Support from other survivors was important due to shared experiences [Reviews: [21, 22]; Papers: [69, 73, 84]].

My kids are my all and being with them keeps me going. Even through what I’m going through now.. They’re like my sun. I see them, and I light up [Paper: [39]]

Yeah when I met fellow survivors at BCF (Breast Cancer Foundation) … yeah … I thought, they also experienced what I have experienced. So it’s OK. It’s not too bad and we laughed about it [Paper: [69]].

Spirituality

Spirituality was important to many survivors in coping with their BC and its ongoing impact on their lives [Reviews: [5, 14, 20,21,22,23,24, 27, 29, 115]; Papers: [39, 41, 47,48,49,50, 78, 94, 97, 102, 103, 109, 114]], as it helped them to cope with uncertainty and accept their condition [Reviews: [5, 20, 21]].

He's chosen me to survive this cancer journey. It's really helpful to me to have a higher power that I choose to call God and to believe that I have a purpose in this world [Review: [5]].

My spirituality and belief in God are so strong and my faith keeps me strong [Paper: [39]]

“We must learn to live with it”

Besides social support and spirituality, women found other ways to cope, including adapting daily activities to accommodate limitations, accepting side-effects and integrating the disease into current life [Reviews: [27, 37, 115]].

I learned to change some of my movements. I learned movements that relieve. Instead of wringing the kitchen glove like that, now I wring it like this, against the side of the sink [Review: [37]].

Others, especially women with advanced BC [Reviews: [5, 21, 22]], and rural BC survivors [Review: [27]], coped through avoidance or denial of their disease, such as trying to forget about their condition [Paper: [90]].

Thinking positively and hopefully, as well as having a ‘fighting spirit’ towards the disease and its ongoing impact, was important for some [Reviews: [5, 21,22,23, 115]; Paperss: [41, 47, 107]].

I believe that a person should be satisfied and not embittered…. Constant anger will cause more disease [Review: [5]]

Many older survivors coped by not having the expectation they would return to full health, as they had already begun to accept declining health as part of aging [Review: [28]]. These survivors focused on their present experience rather than focusing on the past or future [Review: [28]].

Discussion

This meta-review identified and synthesised 25 systematic reviews, and an additional 76 primary papers to describe the psychosocial experience of BC survivors. Overall, the quality of included reviews and papers was mixed, with the majority of studies classified as of moderate quality, suggesting that future research could be improved by following recommended methodological procedures [11]. Some of the included reviews/papers focused on specific groups of BC survivors, including younger/older, rural, ethnic minorities, and survivors with metastatic BC. Return to work was well covered, as was quality of care. Ongoing symptoms (e.g. physical, cognitive, psychological and sexual) was an area of saturation within the included systematic reviews.

Eight of the included systematic reviews were published after the Laidsaar-Powell et al. [15] meta-review and focused on adherence to adjuvant endocrine treatment, rural BC survivors, pain, return to work, sexual problems, metastatic BC, transitioning from patient to survivor, and survivorship characteristics of different BC stages (post-treatment to recurrence and metastatic BC). More recent reviews emphasised ongoing physical and psychological impacts, changes to identity and roles, as well as the transition from patient to survivor. In recent papers, similar topics were covered with many papers focusing on specific populations (e.g. metastatic BC, BC survivors with lymphoedema, low SES, African-American, sexual and gender diverse, young BC survivors) and/or topics (e.g. sexual and reproductive health, cognitive impairment, return to work, posttraumatic growth, cancer-related fatigue).

After combining all of the reviews/papers, the meta-review synthesis resulted in eight overarching themes. A key thread across many of these themes was the challenging transition from patient to survivor; characterised by searching for normalcy, ongoing treatment and side effect impacts, feelings of uncertainty, FCR, lack of information, feeling misunderstood, and changing roles and identity. For many women, this transition was complicated by unmet expectations that once treatment was completed women would return to their healthy premorbid life, which was not a reality for many. Instead, they faced ongoing symptoms and limitations, which in turn led to a sense of being misunderstood by family members and employers. For those women who belonged to an ethnic minority group, challenges could be further exacerbated by difficulties communicating with health professionals and accessing support from within their own communities [24, 25].

These themes reflect the findings of a scoping review by Maheu et al. [117] which focused on uncertainty and FCR in BC survivors. The authors found that the experience of uncertainty was characterised by doubt, liminality, a sense of insecurity, and an inability to meet expectations. Uncertainty was also found to be a cause of FCR. Lack of information and lost connection to health professionals were found to exacerbate both uncertainty and fear of recurrence [117], as was noted in the current study.

While most research reported in this review focused on the ongoing challenges faced by BC survivors, within some reviews women also reported positive aspects of their survivorship experience, including greater appreciation of life. Positive outcomes have been previously identified in survivorship research, emphasising the resilience demonstrated by many cancer survivors [118]. Posttraumatic growth refers to the positive change (or growth) that occurs in individuals after a significant stressor [119, 120]. Reflecting these domains, many cancer survivors report appreciation for the value of life, more self-confidence and self-esteem, positive social interactions and stronger interpersonal relationships, reprioritisation of personal values, as well as strengthened religious faith and spirituality [118, 119] after BC.

Clinical implications

Due to the long-lasting impacts that BC survivors face during their survivorship, highlighted in this review, these women require ongoing support to manage their symptoms and improve both quality of life and metastatic BC survival outcomes [4, 121]. BC survivorship research can inform psychosocial interventions and these should ideally be embedded into established patient care [122]. Interventions may include individualised support, with regular assessment of ongoing challenges and survivorship needs, as well as addressing healthy lifestyle changes, treatment adherence, and symptoms where needed [123]. Support during survivorship should be sustained and more than a one-off consultation [123]. For rural BC survivors, scheduling all appointments on one day and providing support and information via various sources (e.g. social media, internet resources) are suggested ways of improving their health care experience [26].

One important strategy to address the long-term needs of BC survivors is the use of survivorship care plans (SCPs) which are designed to provide support and information during the transition into survivorship [124]. Individualised SCPs created by the oncology treatment team [124] can provide information regarding quality of life and concerns for BC survivors, as well as including plans for follow-up and disease recurrence surveillance [124]. SCPs aim to provide BC survivors with a realistic understanding of what to expect as they transition into survivorship, normalising their feelings of uncertainty. Kozul et al. [125] noted that SCPs can promote discussion of varied survivorship issues, including side effects, FCR, medication adherence, psychosocial/mental health, bone health, difficulties with relationships, exercise, and fertility, and prompt referral to appropriate health professionals for help with these issues.

Interventions aimed specifically at body image, sexuality, and identity may also help women struggling with the impact of BC on their bodies (e.g. after mastectomy) and function (e.g. inability to return to work/care). Morales-Sánchez et al. [126] systematically reviewed eight studies of interventions aimed at improving body image and self-esteem, finding varied effectiveness. Of the interventions, group therapies (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy groups) were found to demonstrate the most positive results. Other interventions, such as psychosexual counselling and intimacy enhancement (couple-based) interventions, have also been found to improve sexuality and intimacy concerns [127, 128].

An important consideration for all interventions is cultural appropriateness. As highlighted in our findings, many women prefer to access support that includes others like them, conforms with their values and beliefs, and which can help them with specific issues such as challenges with language and communication.

Further research

While the current review highlights the large body of evidence examining BC survivorship, several gaps in the evidence base are noted, including BC survivors with BRCA1/2 gene mutations, women receiving tailored treatments (including emerging treatments such as immunotherapy/targeted therapies), those of low socioeconomic status, and the unique experiences of BC survivors with multimorbidity and complex health care needs. While the included reviews discussed the impact of various long-term side-effects of BC and its treatment (e.g. sexual dysfunction, cognitive impairment, psychological distress, loss of fertility, sleep impairment, body image concerns, lymphoedema, ongoing pain, and fatigue), some late effects (emerging months or years after treatment completion) were not covered, including cardiotoxicity and osteoporosis [123, 129]. Lifestyle changes are recommended to reduce risk of cardiotoxicity and osteoporosis including addressing tobacco and alcohol use, managing weight, and increasing exercise [123, 129]. These lifestyle changes may also decrease the risk of recurrence and are therefore commonly part of BC survivorship care [121, 123, 124, 129]. Despite the importance of lifestyle changes in survivorship, this was rarely discussed in the included reviews/papers.

Experiences of gender and sexually diverse BC survivors were also largely missing from the included reviews/papers, reflecting a paucity of research within this area. A recent PP from Brown and McElroy [83] that focused on the unmet needs of sexual and gender minority BC survivors found that these survivors experienced a lack of appropriate support from health care systems and BC survivor organisations.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several limitations. Searches were limited to reviews published in English and, therefore non-English reviews may not have been included. Systematic reviews may be limited by the interpretation provided by these reviews and their choice of quotations, and this review only included primary papers published after the last search made by a systematic review. Therefore, some detail may be missing. Additionally, it is likely that some included reviews drew upon the findings of the same primary papers; therefore, some duplication of results across reviews is possible.

By focusing on qualitative and non-intervention studies, this meta-review may be missing valuable information about the BC survivorship experience. Future studies could incorporate a wider range of research types. Nevertheless, this meta-review is the first to synthesise the available qualitative evidence of BC survivorship and provides the most comprehensive overview of BC survivor experiences to date.

Conclusion

This meta-review synthesised the qualitative BC survivorship evidence base and found that BC survivorship is characterised by many ongoing physical and psychosocial impacts, as well as posttraumatic growth in some women. The quality of research within this meta-review was moderate, and future studies should make use of methodological quality guidelines when conducting systematic reviews and primary research. The findings suggest that BC survivors experience significant uncertainty and changes in identity, along with ongoing physical and psychosocial challenges. It is therefore important to provide timely and accessible support to these women, such as through the use of individualised SCPs. Specialised information about and support for ongoing effects and interventions aimed at body image, sexuality, and identity may be beneficial. To address gaps in the BC research, future studies should include BC survivors with BRCA1/2 gene mutations, women receiving tailored treatments, women from low socioeconomic backgrounds, BC survivors with multimorbidity and complex health care needs, late effects, as well as interventions targeting gender and sexually diverse BC survivors.

Data availability

Data are available within an institutional repository.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Cancer in Australia 2021. https://aihw.gov.au. Accessed 21/12/2022.

Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA). Survivorship care. Critical components of cancer survivorship care in Australia position statement. 2016. https://cosa.org.au.

Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Psychosocial/survivorship issues in breast cancer: are we doing better? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(1):335. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju335.

Smit A, Coetzee BJ, Roomaney R, Bradshaw M, Swartz L. Women’s stories of living with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2019;222:231–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.020.

Carreira H, Williams R, Muller M, Harewood R, Stanway S, Bhaskaran K. Associations between breast cancer survivorship and adverse mental health outcomes: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(12):1311–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy177.

Schmidt ME, Wiskemann J, Steindorf K. Quality of life, problems, and needs of disease-free breast cancer survivors 5 years after diagnosis. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(8):2077–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1866-8.

Mayer M. Lessons learned from the metastatic breast cancer community. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2010;26(3):195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2010.05.004.

Mosher CE, Johnson C, Dickler M, Norton L, Massie MJ, DuHamel K. Living with metastatic breast cancer: a qualitative analysis of physical, psychological, and social sequelae. Breast J. 2013;19(3):285–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.12107.

Holloway I, Galvin K. Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2016.

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):132–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055.

Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-15.

Banning M. Employment and breast cancer: a meta-ethnography. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2011;20(6):708–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01291.x.

Mollica M, Newman SD. Breast cancer in african americans: from patient to survivor. J Transcult Nurs. 2014;25(4):334–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659614524248.

Laidsaar-Powell R, Konings S, Rankin N, Koczwara B, Kemp E, Mazariego C, et al. A meta-review of qualitative research on adult cancer survivors: current strengths and evidence gaps. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(6):852–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00803-8.

Innovation VH. Covidence systematic review software. www.covidence.org.

Programme CAS. Casp qualitative. 2018; Available from: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf.

Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-ethnography: synthesising qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. BMJ. 2009;339(jul21 1):2535–2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Flanigan M, Wyatt G, Lehto R. Spiritual perspectives on pain in advanced breast cancer: a scoping review. Pain Manag Nurs. 2019;20(5):432–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2019.04.002.

Willis K, Lewis S, Ng F, Wilson L. The experience of living with metastatic breast cancer–a review of the literature. Health Care Women Int. 2015;36(5):514–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2014.896364.

Nolan TS, Frank J, Gisiger-Camata S, Meneses K. An integrative review of psychosocial concerns among young african american breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(2):139–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000477.

Russell KM, Von Ah DM, Giesler RB, Storniolo AM, Haase JE. Quality of life of african american breast cancer survivors: how much do we know? Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(6):E36-45. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000339254.68324.d7.

Wen KY, Fang CY, Ma GX. Breast cancer experience and survivorship among asian americans: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(1):94–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0320-8.

Yoon H, Chatters L, Kao TS, Saint-Arnault D, Northouse L. Factors affecting quality of life for korean american cancer survivors: an integrative review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2016;43(3):E132–42. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.ONF.E132-E142.

Anbari AB, Wanchai A, Graves R. Breast cancer survivorship in rural settings: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(8):3517–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05308-0.

Bettencourt BA, Schlegel RJ, Talley AE, Molix LA. The breast cancer experience of rural women: a literature review. Psychooncol. 2007;16(10):875–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1235.

Campbell-Enns HJ, Woodgate RL. The psychosocial experiences of women with breast cancer across the lifespan: a systematic review. Psychooncol. 2017;26(11):1711–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4281.

Chang YC, Chang SR, Chiu SC. Sexual problems of patients with breast cancer after treatment: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42(5):418–25. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000592.

Vivar CG, McQueen A. Informational and emotional needs of long-term survivors of breast cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51(5):520–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03524.x.

Zomkowski K, Cruz de Souza B, Pinheiro da Silva F, Moreira GM, de Souza Cunha N, Sperandio FF. Physical symptoms and working performance in female breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;40(13):1485–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1300950.

Tiedtke C, de Rijk A, Dierckx de Casterle B, Christiaens MR, Donceel P. Experiences and concerns about “returning to work” for women breast cancer survivors: a literature review. Psychooncol. 2019;19(7):677–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1633.

Bijker R, Duijts SFA, Smith SN, de Wildt-Liesveld R, Anema JR, Regeer BJ. Functional impairments and work-related outcomes in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(3):429–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9736-8.

Selamat MH, Loh SY, Mackenzie L, Vardy J. Chemobrain experienced by breast cancer survivors: a meta-ethnography study investigating research and care implications. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108002. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108002.

Henneghan A. Modifiable factors and cognitive dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: a mixed-method systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(1):481–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2927-y.

AlOmeir O, Patel N, Donyai P. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among breast cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature using grounded theory. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(11):5075–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05585-9.

Armoogum J, Harcourt D, Foster C, Llewellyn A, McCabe CS. The experience of persistent pain in adult cancer survivors: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2020;29(1):e13192. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13192.

Goncalves V, Sehovic I, Quinn G. Childbearing attitudes and decisions of young breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(2):279–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt039.

Adler SR, Coulter YZ, Stone K, Glaser J, Duerr M, Enochty S. End-of-life concerns and experiences of living with advanced breast cancer among medically underserved women. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(6):959–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.08.006.

Alfieri S, Brunelli C, Capri G, Caraceni A, Bianchi GV, Borreani C. A qualitative study on the needs of women with metastatic breast cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01954-4.

Ginter AC. “The day you lose your hope is the day you start to die”: quality of life measured by young women with metastatic breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2020;38(4):418–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2020.1715523.

Lee Mortensen G, Madsen IB, Krogsgaard R, Ejlertsen B. Quality of life and care needs in women with estrogen positive metastatic breast cancer: a qualitative study. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(1):146–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2017.1406141.

Lundquist DM, Berry DL, Boltz M, DeSanto-Madeya SA, Grace PJ. Wearing the mask of wellness: the experience of young women living with advanced breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2019;46(3):329–37. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.ONF.329-337.

Mosher CE, Daily S, Tometich D, Matthias MS, Outcalt SD, Hirsh A, et al. Factors underlying metastatic breast cancer patients' perceptions of symptom importance: a qualitative analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12540

Oostra DL, Burse NR, Wolf LJ, Schleicher E, Mama SK, Bluethmann S, et al. Understanding nutritional problems of metastatic breast cancer patients: Opportunities for supportive care through ehealth. Cancer Nurs. 2020;44(2):154–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000788.

Ceballos RM, Hohl SD, Molina Y, Hempstead B, Thompson-Dodd J, Weatherby S, et al. Oncology provider and african-american breast cancer survivor perceptions of the emotional experience of transitioning to survivorship. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021;39(1):35–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2020.1752880.

Davis CM, Nyamathi AM, Abuatiq A, Fike GC, Wilson AM. Understanding supportive care factors among african american breast cancer survivors. J Transcult Nurs. 2018;29(1):21–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659616670713.

Ford YR. Stories of african-american breast cancer survivors. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2019;30(2):26–33.

Nolan TS, Ivankova N, Carson TL, Spaulding AM, Dunovan S, Davies S, et al. Life after breast cancer: “being” a young African American survivor. Ethn Health. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2019.1682524.

Yan AF, Stevens P, Holt C, Walker A, Ng A, McManus P, et al. Culture, identity, strength and spirituality: a qualitative study to understand experiences of african american women breast cancer survivors and recommendations for intervention development. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28(3):e13013. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13013.

Black KZ, Eng E, Schaal JC, Johnson LS, Nichols HB, Ellis KR, et al. The other side of through: young breast cancer survivors’ spectrum of sexual and reproductive health needs. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(13):2019–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320929649.

Henneghan A, Phillips C, Courtney A. We are different: young adult survivors’ experience of breast cancer. Breast J. 2018;24(6):1126–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.13128.

Hubbeling HG, Rosenberg SM, Gonzalez-Robledo MC, Cohn JG, Villarreal-Garza C, Partridge AH, et al. Psychosocial needs of young breast cancer survivors in mexico city, mexico. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0197931. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197931.

Milosevic E, Brunet J, Campbell KL. Exploring tensions within young breast cancer survivors’ physical activity, nutrition and weight management beliefs and practices. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(5):685–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1506512.

Raque-Bogdan TL, Hoffman MA, Joseph EC, Ginter AC, White R, Schexnayder K, et al. Everything is more critical: a qualitative study of the experiences of young breast cancer survivors. Couns Values. 2018;63(2):210–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/cvj.12089.

Rees S. A qualitative exploration of the meaning of the term “survivor” to young women living with a history of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2018;27(3):e12847. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12847.

Wilson E. Social work, cancer survivorship and liminality: meeting the needs of young women diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. J Soc Work Pract. 2020;34(1):95–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2019.1604497.

Gorman JR, Smith E, Drizin JH, Lyons KS, Harvey SM. Navigating sexual health in cancer survivorship: a dyadic perspective. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(11):5429–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05396-y.

Bilodeau K, Tremblay D, Durand MJ. Return to work after breast cancer treatments: Rebuilding everything despite feeling “in-between.” Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;41(165):165–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2019.06.004.

Bilodeau K, Tremblay D, Durand MJ. Gaps and delays in survivorship care in the return-to-work pathway for survivors of breast cancer-a qualitative study. Curr Oncol. 2019;26(3):e414–7. https://doi.org/10.3747/co.26.4787.

Caron M, Durand MJ, Tremblay D. Perceptions of breast cancer survivors on the supporting practices of their supervisors in the return-to-work process: a qualitative descriptive study. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(1):89–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9698-x.

Fassier JB, Lamort-Bouche M, Broc G, Guittard L, Peron J, Rouat S, et al. Developing a return to work intervention for breast cancer survivors with the intervention mapping protocol: challenges and opportunities of the needs assessment. Front Publ Health. 2018;6:35. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00035.

Luo SX, Liu JE, Cheng ASK, Xiao SQ, Su YL, Feuerstein M. Breast cancer survivors report similar concerns related to return to work in developed and developing nations. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(1):42–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-018-9762-1.

Sengun Inan F, Gunusen N, Ozkul B, Akturk N. A dimension in recovery: return to working life after breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(6):E328–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000757.

Sun Y, Shigaki CL, Armer JM. The influence of breast cancer related lymphedema on women’s return-to-work. Womens Health (Lond). 2020;16:1745506520905720. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745506520905720.

van Maarschalkerweerd PEA, Schaapveld M, Paalman CH, Aaronson NK, Duijts SFA. Changes in employment status, barriers to, and facilitators of (return to) work in breast cancer survivors 5–10 years after diagnosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(21):3052–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1583779.

Zomkowski K, Cruz de Souza B, Moreira GM, Volkmer C, Da Silva Honorio GJ, Moraes Santos G, et al. Qualitative study of return to work following breast cancer treatment. Occup Med (Lond). 2019;69(3):189–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqz024.

Bolton G, Isaacs A. Women’s experiences of cancer-related cognitive impairment, its impact on daily life and care received for it following treatment for breast cancer. Psychol Health Med. 2018;23(10):1261–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2018.1500023.

Henderson FM, Cross AJ, Baraniak AR. “A new normal with chemobrain”: experiences of the impact of chemotherapy-related cognitive deficits in long-term breast cancer survivors. Health Psychol Open. 2019;6(1):2055102919832234. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102919832234.

Anbari AB, Wanchai A, Armer JM. Breast cancer-related lymphedema and quality of life: a qualitative analysis over years of survivorship. Chronic Illn. 2019;17(3):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395319872796.

Dean LT, Moss SL, Ransome Y, Frasso-Jaramillo L, Zhang Y, Visvanathan K, et al. “It still affects our economic situation”: long-term economic burden of breast cancer and lymphedema. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(5):1697–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4418-4.

Ostby PL, Armer JM, Smith K, Stewart BR. Patient perceptions of barriers to self-management of breast cancer-related lymphedema. West J Nurs Res. 2018;40(12):1800–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945917744351.

Kim S, Han J, Lee MY, Jang MK. The experience of cancer-related fatigue, exercise and exercise adherence among women breast cancer survivors: insights from focus group interviews. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(5–6):758–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15114.

Levkovich I, Cohen M, Karkabi K. The experience of fatigue in breast cancer patients 1–12 month post-chemotherapy: a qualitative study. Behav Med. 2019;45(1):7–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2017.1399100.

Penner C, Zimmerman C, Conboy L, Kaptchuk T, Kerr C. “Honorable toward your whole self”: experiences of the body in fatigued breast cancer survivors. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1502. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01502.

Haeng-Mi S, Park EY, Eun-Jeong K. Cancer-related fatigue of breast cancer survivors: qualitative research. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2020;20(4):141–9. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2020.20.4.141.

Canzona MR, Fisher CL, Ledford CJW. Perpetuating the cycle of silence: The intersection of uncertainty and sexual health communication among couples after breast cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(2):659–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4369-9.

Fouladi N, Pourfarzi F, Dolattorkpour N, Alimohammadi S, Mehrara E. Sexual life after mastectomy in breast cancer survivors: a qualitative study. Psychooncol. 2018;27(2):434–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4479.

Tat S, Doan T, Yoo GJ, Levine EG. Qualitative exploration of sexual health among diverse breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Educ. 2018;33(2):477–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-016-1090-6.

Stalsberg R, Eikemo TA, Lundgren S, Reidunsdatter RJ. Physical activity in long-term breast cancer survivors - a mixed-methods approach. Breast. 2019;46:126–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2019.05.014.

Chumdaeng SSH, Chontawan R, Soivong P. Health behavior changes among survivors of breast cancer after treatment completion. Pacific Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2020;24(4):472–84.

Enzler CJ, Torres S, Jabson J, Ahlum Hanson A, Bowen DJ. Comparing provider and patient views of issues for low-resourced breast cancer patients. Psychooncol. 2019;28(5):1018–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5035.

Brown MT, McElroy JA. Unmet support needs of sexual and gender minority breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(4):1189–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3941-z.

Azulay Chertok IR, Wolf JH, Beigelman S, Warner E. Infant feeding among women with a history of breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(3):356–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00852-z.

Brennan L, Kessie T, Caulfield B. Patient experiences of rehabilitation and the potential for an mhealth system with biofeedback after breast cancer surgery: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(7):e19721. https://doi.org/10.2196/19721.

Cherif E, Martin-Verdier E, Rochette C. Investigating the healthcare pathway through patients’ experience and profiles: implications for breast cancer healthcare providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):735. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05569-9.

Rafn BS, Midtgaard J, Camp PG, Campbell KL. Shared concern with current breast cancer rehabilitation services: a focus group study of survivors’ and professionals’ experiences and preferences for rehabilitation care delivery. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e037280. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037280.

Faccio F, Mascheroni E, Ionio C, Pravettoni G, Alessandro Peccatori F, Pisoni C, et al. Motherhood during or after breast cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2020;29(2):e13214. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13214.

Inan FS, Ustun B. Post-traumatic growth in the early survival phase: from turkish breast cancer survivors’ perspective. Eur J Breast Health. 2020;16(1):66–71. https://doi.org/10.5152/ejbh.2019.5006.

Lai WS, Shu BC, Hou WL. A qualitative exploration of the fear of recurrence among taiwanese breast cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28(5):e13113. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13113.

Maheu C, Hebert M, Louli J, Yao TR, Lambert S, Cooke A, et al. Revision of the fear of cancer recurrence cognitive and emotional model by lee-jones et al with women with breast cancer. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2019;2(4):e1172. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnr2.1172.

Sengun Inan F, Ustun B. Fear of recurrence in turkish breast cancer survivors: a qualitative study. J Transcult Nurs. 2019;30(2):146–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659618771142.

Lambert LK, Balneaves LG, Howard AF, Chia SK, Gotay CC. Understanding adjuvant endocrine therapy persistence in breast cancer survivors. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):732. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4644-7.

Toledo G, Ochoa CY, Farias AJ. Religion and spirituality: their role in the psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer and subsequent symptom management of adjuvant endocrine therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(6):3017–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05722-4.

Jakobsen K, Magnus E, Lundgren S, Reidunsdatter RJ. Everyday life in breast cancer survivors experiencing challenges: a qualitative study. Scand J Occup Ther. 2018;25(4):298–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2017.1335777.

Keesing S, Rosenwax L, McNamara B. The implications of women’s activity limitations and role disruptions during breast cancer survivorship. Womens Health (Lond). 2018;14:1745505718756381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745505718756381.

Keesing S, Rosenwax L, McNamara B. A call to action: The need for improved service coordination during early survivorship for women with breast cancer and partners. Women Health. 2019;59(4):406–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2018.1478362.

Kim SH, Park S, Kim SJ, Hur MH, Lee BG, Han MS. Self-management needs of breast cancer survivors after treatment: results from a focus group interview. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(1):78–85. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000641.

Knaul FM, Doubova SV, Gonzalez Robledo MC, Durstine A, Pages GS, Casanova F, et al. Self-identity, lived experiences, and challenges of breast, cervical, and prostate cancer survivorship in mexico: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):577. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07076-w.

Liska A, Lamontagne A, Sambrooke K, Snowdon A, Mitchell F. A patient’s perspective: Bridging the transition following radiation therapy for patients with breast cancer. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2020;51(4S):S72–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmir.2020.08.008.

Pembroke M, Bradley J, Nemeth LS. Breast cancer survivors’ unmet needs after completion of radiation therapy treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2020;47(4):436–45. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.ONF.436-445.

Pintado S. Breast cancer patients’ search for meaning. Health Care Women Int. 2018;39(7):771–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2018.1465427.

Dsouza SM, Vyas N, Narayanan P, Parsekar SS, Gore M, Sharan K. A qualitative study on experiences and needs of breast cancer survivors in Karnataka India. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2018;6:69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2017.08.001.

Rashidi E, Morda R, Karnilowicz W. “I will not be defined by this. I’m not going to live like a victim; it is not going to define my life”: exploring breast cancer survivors’ experiences and sense of self. Qual Health Res. 2021;31(2):349–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320968069.

Cheng KKF, Cheng HL, Wong WH, Koh C. A mixed-methods study to explore the supportive care needs of breast cancer survivors. Psychooncol. 2018;27(1):265–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4503.

Chen SQ, Sun N, Ge W, Su JE, Li QR. The development process of self-acceptance among chinese women with breast cancer. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2020;17(2):e12308. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12308.

Drageset S, Lindstrom TC, Ellingsen S. “I have both lost and gained” Norwegian survivors’ experiences of coping 9 years after primary breast cancer surgery. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(1):E30–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000656.

Chao YH, Wang SY, Sheu SJ. Integrative review of breast cancer survivors’ transition experience and transitional care: dialog with transition theory perspectives. Breast Cancer. 2020;27(5):810–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-020-01097-w.

Rapport F, Khanom A, Doel MA, Hutchings HA, Bierbaum M, Hogden A, et al. Women’s perceptions of journeying toward an unknown future with breast cancer: the “lives at risk study.” Qual Health Res. 2018;28(1):30–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317730569.

Schwartz NA, von Glascoe CA. The body in the mirror: breast cancer, liminality and borderlands. Med Anthropol. 2021;40(1):64–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2020.1775220.

Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G, Mutsaers B, Thewes B, Prins J, et al. From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3265–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3272-5.

BinshaPappachan C, D’Silva F, Safeekh AT. Life beyond the diagnosis of breast cancer: a qualitative study on the lived experiences of breast cancer survivors. Indian J Publ Health Res Dev. 2020;11(3):73–7. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijphrd.v11i3.688.

Sun L, Ang E, Ang WHD, Lopez V. Losing the breast: a meta-synthesis of the impact in women breast cancer survivors. Psychooncol. 2018;27(2):376–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4460.

Chuang LY, Hsu YY, Yin SY, Shu BC. Staring at my body: the experience of body reconstruction in breast cancer long-term survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(3):E56–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000507.

Gotay CC, Muraoka MY. Quality of life in long-term survivors of adult-onset cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(9):656–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/90.9.656.

Llewellyn A, Howard C, McCabe C. An exploration of the experiences of women treated with radiotherapy for breast cancer: learning from recent and historical cohorts to identify enduring needs. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2019;39:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2019.01.002.

Maheu C, Singh M, Tock WL, Eyrenci A, Galica J, Hebert M, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence, health anxiety, worry, and uncertainty: a scoping review about their conceptualization and measurement within breast cancer survivorship research. Front Psychol. 2021;12:644932. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644932.

Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Recovery issues in cancer survivorship: a new challenge for supportive care. Cancer J. 2006;12(5):432–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/00130404-200609000-00012.

Stanton AL, Bower JE, Low CA. Posttraumatic growth after cancer. In: Tedeschi LCR, editor. Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practic. Place: Published; 2014. p. 152–89.

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(3):455–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02103658.

Zdenkowski N, Tesson S, Lombard J, Lovell M, Hayes S, Francis PA, et al. Supportive care of women with breast cancer: key concerns and practical solutions. Med J Aust. 2016;205(10):471–5. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja16.00947.

Jacobsen PB, Wagner LI. A new quality standard: the integration of psychosocial care into routine cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1154–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5046.

Moore HCF. Breast cancer survivorship. Semin Oncol. 2020;47(4):222–8. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2020.05.004.

Post KE, Moy B, Furlani C, Strand E, Flanagan J, Peppercorn JM. Survivorship model of care: development and implementation of a nurse practitioner-led intervention for patients with breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(4):E99–105. https://doi.org/10.1188/17.CJON.E99-E105.

Kozul C, Stafford L, Little R, Bousman C, Park A, Shanahan K, et al. Breast cancer survivor symptoms: a comparison of physicians’ consultation records and nurse-led survivorship care plans. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2020;24(3):E34–42. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.CJON.E34-E42.

Morales-Sanchez L, Luque-Ribelles V, Gil-Olarte P, Ruiz-Gonzalez P, Guil R. Enhancing self-esteem and body image of breast cancer women through interventions: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041640.

Fatehi S, Maasoumi R, Atashsokhan G, Hamidzadeh A, Janbabaei G, Mirrezaie SM. The effects of psychosexual counseling on sexual quality of life and function in iranian breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;175(1):171–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05140-z.

Reese JB, Smith KC, Handorf E, Sorice K, Bober SL, Bantug ET, et al. A randomized pilot trial of a couple-based intervention addressing sexual concerns for breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(2):242–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1510869.

Nardin S, Mora E, Varughese FM, D’Avanzo F, Vachanaram AR, Rossi V, et al. Breast cancer survivorship, quality of life, and late toxicities. Front Oncol. 2020;10:864. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00864.

ALmegewly W, Gould D, Anstey S. Hidden voices: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of surviving breast cancer in saudi arabia. J Res Nurs. 2019;24(1–2):122–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987118809482.

Currin-McCulloch J, Stanton A, Boyd R, Neaves M ,Jones B. Understanding breast cancer survivors' information-seeking behaviours and overall experiences: a comparison of themes derived from social media posts and focus groups. Psychol Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2020.1792903

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by King R and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

As this was a meta-review and systematic review, no individual participants were involved, and consent was not necessary to obtain.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

R., K., L., S., P., B. et al. Psychosocial experiences of breast cancer survivors: a meta-review. J Cancer Surviv 18, 84–123 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01336-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01336-x